Figure 15.1

Map of Japan by regions (Source: Inoue, 2007, http://www.freemap.jp/php/japan_nurinuri_1_1/japan_nurinuri.html)

Chapter 15

From Saké to Sea Urchin: Food and Drink Festivals and Regional Identity in Japan

The geographical and historic foundations of Japan have imprinted regional distinctions on food and drink products, and these have become part of the basis of cultural traditions, identity and festivals. Although parts of Japan such as Tokyo and Kobe are taking on more of a cosmopolitan feeling to them, there is still a very strong link to local communities all over Japan through traditional festivals and events that occur throughout the year. Regions have become known for specific food and drink products with regions claiming ownership over these products and celebrating them through festivals. The national government has set up a series of community development projects and implemented new laws setting the foundation for festivals and events celebrating the harvest or production. Examples include the Sea Urchin festival in Haboro in northern Japan to Doburoku (unrefined saké) festivals in Ota, Kyushu in southern Japan. Although Japanese festivals that accompany food and/or wine usually have a long history, many festivals that ‘feature’ food and drink are rather new. Some of the festivals have been created or re-created in order to rejuvenate declining rural communities and it is believed that the success of these festivals will enhance the local people’s regional identity, self-efficacy, and pride.

Many foreigners visiting Japan immediately notice the Japanese people’s love for food and drink. Food and delicatessen sections in grocery stores and department stores are well stocked with artistic nouvelle cuisine as well as various side dishes that accompany meals. Many food festivals linked to the harvest have long traditions and are celebrated across Japan throughout the year. There are plentiful magazines featuring food and drink. On TV, there are numerous shows highlighting local cuisine, nouvelle cuisine, and international cuisine. Travel brochures and web sites have event databases and one can search by the category ‘Food and Drink’. Although the day-to-day food consumption of the average Japanese household is modest, regional ‘food and drink’ components have become an important entertainment element for any festive occasion.

The Japanese are also known for their obsession with fresh ingredients. The TV show’ Iron Chef’ (invited guest chef challenges resident master chef in a 1 hour cooking battle with a selected theme ingredient) was well received both inside and outside of Japan and emphasized the Japanese chef’s obsession with fresh, high-quality ingredients along with artistic presentations of the final product (Fuji Television, 2000). The Japanese idea of the ‘best’ food is fresh, preferably alive, and the ingredients are to be consumed as it is being cooked, with little intervention of condiments. Based on this belief, Japanese festivals and events that feature food and/or drink focus on ‘in season’, ‘freshness’, or ‘just taken out of (water or field)’. Food festivals and events emphasize the ‘localness’, ‘uniqueness to the area’, and that the ‘product is available only for a short period of time’.

This chapter will explore the evolutionary nature of Japanese food and drink festivals. The chapter begins by examining the relationship between regional identity and regional food ways in order to understand current trends in food festivals. It is argued that it is vital to understand the historical, geographical, and socio-political factors that have contributed to create the Japanese passion for regional food and food festivals. With the background set, the chapter turns to examine the changing nature of food festivals and the political, socio-cultural, and economic motivators behind the shift towards non-traditional, event-style food festivals. The chapter concludes by highlighting some of the challenges food festivals and events face now and will face in the future. This chapter emphasizes the importance of understanding the evolution of regional food and unique food ways, and how they have been adopted to create new ‘food and drink’ festivals in Japan.

Regional Identity and Food ways

Japan today is often considered a culturally homogenous nation because only 1.5 per cent of population is registered as non-Japanese nationals. The evidence shows that various ethnic groups including the indigenous ‘Wa’ (or ‘Yamato’, the ancient Japanese ethnic group) along with others from the Asian mainland as well as from northern and southern islands settled in the Japanese archipelago over thousands of years and formed a culture known as ‘Japanese’ culture. However the distinct cultural characteristics of northern Ainu and southern Okinawan are still visible.

Nevertheless the internal geography of Japan (high mountains and islands with limited links) isolated many settlements, resulting in clear regional distinctions in dialects and food ways. Such regional differences were identified in the early part of history. By the time the first constitution was established (702 AD) the imperial court were enjoying regional delicacies and unique food ingredients as part of the levy paid to it. There is a record showing how Lord Masamuné Daté of Sendai, who was a known gourmand, entertained the Shogun with delicacies from all around Japan, prepared by Lord Daté himself in 1630. Another menu for Lord Daté’s New Year’s meals shows that they were made only from ingredients from his feudal territory (Food Kingdom Miyagi, 2007).

Although Japan is geographically small, various microclimates and geographical features contribute to the development of regional dishes and known food products (Figure 15.1 provides a map of Japan). Regional dishes may also be created to boost local morale or distinguish a community from others. Yet, the regional food is a powerful way to express territories and identities (Bell and Valentine, 1997; Avieli, 2005). Prof. Emeritus Yamano is warning about the loss of national identity among Japanese as the Japanese diet is progressively being westernized (Shigeto, 2005). The foundation of the Slow Food Japan network emphasizes the protection of regional dishes and foodstuff, and the diversification of diet among Japanese population (http://www.slowfoodjapan.net/index.html). The Chisan Chisho (locally produced, locally consumed) movement is also contributing to the protection of traditional regional food and to regional festivals.

Figure 15.1

Map of Japan by regions (Source: Inoue, 2007, http://www.freemap.jp/php/japan_nurinuri_1_1/japan_nurinuri.html)

Political and Social Climate Influences on food Festivals

As mentioned in the introduction, it is not only the geographical foundations which have imprinted their mark on food festivals, it is also the historical development in food ways which have greatly influenced food festivals. Historical and social changes present the framework for understanding food consumption patterns. As will be illustrated below, the government has taken recent legal action to strengthen and celebrate traditional food products which have become the basis for many food festivals.

In 3 BC rice farming came from Mainland China. When trade with China was established in 7 AD, different kinds of vegetables and fruits were introduced; a new way of cooking with oil, drinking cow’s milk, and consuming dairy products became fashionable among aristocrats. Meanwhile, the introduction of Buddhism forbade the consumption of meat. The Meiji era (1868–1912) was a pivotal point in Japanese history and the Japanese diet and food ways also changed. Meat consumption became fashionable among the aristocrats (Zenkoku Joho Gakushu Shinko Kyokai, n.d.). However consumption of meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products was extremely rare among the lower classes (Dokkyo University, 1998; Onshindo Pharmacy, 2007). The post-World War II period was another pivotal point in terms of Japanese diets. During the recovery period, the American Government’s ‘PL 480: Food for Peace’ supplies from the USA nearly replaced the traditional Japanese diet with wheat products (bread, baked goods) and highly concentrated milk powder (Suzuki, 2003; Makino, 2007). Excessive amount of protein and fats were introduced through the consumption of meat/poultry, eggs, and dairy products. The Japanese began to eat less and less rice and consumed more and more fish, meat, and dairy products. Recently the Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry (MAFF, 2005a) identified an increase in diabetes and osteoporoses which can be attributed to an unbalanced diet. MAFF warns that the trend of increasing bad eating habits, unbalanced diet, complacency, and laziness drawn from a convenient life style are becoming a threat to Japanese food ways (MAFF, n.d.).

Today’s Japan is an ageing nation. By 2050, the population is projected to decrease to 100 million people, and by 2100 it will be around 67 million (one-half of the 2007 population) (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2000). Globalization brings fusion of culture and values, and the blurring of distinctions between traditions and cultural practices. In addition to the rise of globalization, the older generations who can teach traditions and customs are disappearing. Globalization in food culture also affects food safety and the health of Japanese.

With such a background, four government-initiated laws and movements have supported the increasing focus on food and the rise of food festivals in Japan. These are (1) Basic Law on Shokuiku [Food Education], enacted in June 2005 (MAFF, n.d.); (2) Omatsuri hou: Law Concerning the Promotion of Sightseeing and Commerce and Industry in Designated Areas by Organizing Events Taking Advantage of Traditional Music, Arts and Other Local Cultures (Haitani, 1996), began in 1992; (3) Chisan Chisho [locally grown, locally consumed] movement started in the 1980s, in conjunction with the Slow Food movement, which started in 2000 in Japan (Slow Food Japan, 2007); and (4) One Village One Product movement started in 1979 (OVOP, n.d.). These are described below in more detail as well as how they have influenced festival development.

The Shokuiku basic law was to promote a healthier body and mind through increasing Japanese people’s knowledge to nutrition and a balanced diet. The specific aim is to raise ‘awareness and appreciation of traditional Japanese food culture as well as educate people about food supply/demand networks as part of these opportunities of interaction between food producers and consumers were created. This was done in order to revitalize rural farming and fishing regions and to boost food self-sufficiency in Japan’ (MAFF, n.d., p. 3). The law promotes education and awareness through school and with the knowledge people seek out food festivals.

The Omatsuri Law came in to practice after a Japanese site was recently designated as a UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site and the national interest in culture and heritage was heightened. Local community revitalization projects utilizing traditional events and cultural, including regional cuisine, were encouraged under this law. Many peripheral communities took advantage of this law and started food events/festivals to promote tourism revenues.

The Chisan Chisho, Slow Food and OVOP movements were originally meant to improve farming communities’ well-being and ensure food safety. The focus was increasing self-sufficiency in agriculture and aquaculture products, bringing producers and the consumers together. The movement was seen as way to combat over-reliance on imported food, ensuring superior food safety of local produce over imported food, nurturing pride in local produce, and giving the depopulating and slowly dying rural communities opportunities to revitalize (MAFF, 2005b,c; Slow Food Japan, 2007; OVOP, n.d.). The OVOP programme links participating villages to one product, which they become known for and this is used in tourism marketing. At railway stations, for example, signs are posted alerting the travellers which product each village is known for. These products have been incorporated into food festivals attracting tourists.

With government campaigns such as those above, it is no wonder that numerous food festivals have been encouraged and have materialized in recent years. Many of these are modified versions of existing or traditional festivals and events. Reflecting the Japanese love for food and drink as part of entertainment, most of the festivals focus on food and drink; even if they are not the main attraction. The festival/event cannot survive without food and drink as added value. In most cases, the food and drink provided at festivals are unique to the area. Moreover, this uniqueness of dishes or the ingredients are the products of Japanese geography and climate.

History of Festivals and Speciality food

Although traditional Japanese meals today are drawing attention worldwide as often ‘diet food’, contemporary Japanese meals contains more protein and fat than meals several decades ago. With the influence from the western world, Japanese meals are resembling festival meals of old which tend to emphasize more fish, meat, and poultry side dishes than rice, cereals, and vegetables.

In an agrarian society, festivals and events gave purpose and expectations in repetitive and laborious ordinary workdays. Special events such as wedding and funerals, religious events, national/regional events were classified as Haré (non-ordinary or festive) while daily labour and rest are classified as Ké (ordinary) (Machida, 2002; Fujigoko, 2007; Makino, 2007). The time and space for Haré were set aside so that the ‘festivity’ was a totally different event from day-to-day activities. New Year’s Day, weddings and funerals, religious rituals and performances, and Noh and Kyogen Dance Performances were some examples. Many Haré events are also linked to religious/spiritual events, focusing on prayers for healthy growth of crops and plentiful harvests, blessing on children’s growth, warding off illness, injuries and bad luck, and for business prosperity (Fujigoko, 2007; Toshi Noson Gyoson Koryu Kasseika Kikou, 2007).

On Haré occasions, everyone dresses up in his or her best outfits and eats special meals. Valuable foodstuff such as refined white rice (Machida, 2002), rice cakes made from glutinous rice (Makino, 2007), and saké (Segawa, 2001) were only consumed at Haré occasions. Festive meals often reflects seasons – e.g. fish in season, seasonal vegetables, seasonal rice cakes, noodles of the season, and so on (Makino, 2007). Traditional Haré cuisine also bore symbolic meanings through word punning and the nature of the food. For instance, a kelp (kobu) dish was prepared to receive happiness (yoro kobu); Red snapper (tai) is also for being festive and happy (medetai); salt-cured herring roe was for abundant offspring.

One example of festive food is Sushi. Up until the 1970s, Sushi was a special occasion food. Originating from Naré Sushi or Naré Zushi, it was invented in the fourth century AD in Asia. Naré zushi was believed to have reached Japan from southern China in the eighth century (Sushi Master, 2000). Naré zushi is the term used for fermented fish and rice was used to accelerate fermentation. The rice breaks down in the fermentation process and is discarded. However, Japanese turned it into a semi-fermented food so that rice can be consumed as well. This version of ‘Naré zushi’ spread all over Japan and different kinds of fish available in the regions were used. It is commonly believed that the word Sushi means ‘sour’ rice, though contemporary characters for the word ‘sushi’ denotes happiness. The etymology reveals that the old characters for the word described marinated or fermented fish and fish source (Wikipedia, 2007a). In the nineteenth century, in the Tokyo area sushi chefs began to use fresh fish from Tokyo Bay. Rice was cooked and vinegar was added instead of waiting for natural fermentation (Sushi Master, 2000). This became the predecessor of today’s Nigiri zushi. After the Kanto Earthquake in 1923, sushi chefs left devastated Tokyo and returned to their home regions to spread this form of sushi nationwide (Sushi Master, 2000; Wikipedia, 2007a). However, other than Tokyo-style Nigiri zushi, there are regional versions of sushi independently developed from Naré zushi. In Wakayama prefecture, local ayu (sweetfish) is used; in Akita prefecture, hata-hata (sandfish) is used. To illustrate regional development of sushi, in Kansai (Kyoto-Osaka area), there are Futomaki (various ingredients and rice rolled up in sea weed), Battera (vinegar-cured Mackerel box sushi), Kaki-no-ha zushi (salt-cured Mackerel sushi wrapped in persimmon leaves), just to name a few. However, the common homemade sushi is Chirashi (or Bara) zushi. Preserved or fresh vegetables are prepared and finely chopped and mixed with vinegar-added rice. This kind of sushi is not shaped and simply covered with local seafood, eggs, fresh greens, or even local fruit for decoration (Wikipedia, 2007a).

Beside sushi, people tend to eat more elaborate ‘side dishes’ than rice and cereal at festive occasions, i.e. more fish, shell fish, and recently more meat and poultry. Even the rice eaten is refined white rice. Unlike Ké (ordinary) occasions, the amount of fat and animal protein intake has become quite high (Onshindo Pharmacy, 2007). When recent festive meals were examined, Makino (2007) found that more westernized food (e.g. steak, Salisbury steak, BBQ meat, French fries/pommes frit, deep fried chicken) was preferred. She also found that the traditional festive food varieties were consumed more in southwestern parts of Japan.

Changing Concept of Haré (Non-Ordinary) and Festivals and Events Today

Pagan animism, which developed into the Shinto religion, demanded an intimate relationship between nature and human life. Spring and autumn are the seasonal turning points when appeasing the deities and spirits will ensure health and growth in harsh seasons (summer and winter). Origuchi (2004) notes that ancient festivals in Japan were conducted only in autumn and spring. There was also a winter festival, which was often performed as a preparation for the spring festival, then later it became a festival on its own right. There was no summer festival yet the summer purification ritual (hojo-é) was combined with music and dance entertainment and transformed into a summer festival. This custom of adding entertainment to rit-uals can be observed from the beginning of Heian Period (794–1185 AD) (Origuchi, 2004).

These festivals are purely for the blessing of the crops, warding off disease, appeasing deities and lesser evils, and giving thanks for a bountiful harvest. Doburoku (unrefined saké) has been used as part of Shinto rituals in autumn festivals. The Doburoku festival of Shirahige Shrine in Oita prefecture has a recorded history since 710 AD. The Omori Shrine in Mié prefecture started its Doburoku festival in 1213 AD. Doburoku is, by law, illegal if brewed and consumed outside the ‘designated areas’. The strict 2002 law was modified in 2004 and the number of the designated areas is increasing. When the law was relaxed in 2004, various villages applied for permission to brew Doburoku as part of a community development project. Today, 16 prefectures have designated areas (43 shrines, some designated Doburoku breweries, and inn/restaurants) (Satomi, 2005).

It has been observed that traditional festivals in the remote areas of Japan have begun to disappear mainly due to lack of resources. On the other hand, there is a phenomenon that ‘organizers’ create new festivals. The removal of authority or spirituality of traditional festivals is apparent in the new festivals. Hasegawa (2002) summarizes two types of contemporary festivals (Figure 15.2):

Figure 15.2

Two types of festivals (adapted from Hasegawa, Non-participatory 2002)

Hasegawa (2002) further identified from his research results that the above two types exist on two continua. The first is religious to non-religious continuum and the second is on the level of participation of visitors in the festivals.

The traditional festivals were meant for temporal and spatial purification and energizing events by inviting the Haré (nonordinary) power of spirits and deities. However, contemporary events only pursue Haré occasions, at a time and place where people can leave the ordinary life behind and enjoy themselves in a non-ordinary environment. Hirai (2002) emphasizes the recent rapid emergence and growth in event-style festivals. Some of these event-style festivals already have a history of 50 or more years. The initial motivation to start the event varies. The Tanabata Festival in Shigehara city, Chiba-prefecture, was started as a street event in the shopping area to attract more visitors during the low business season. Yosakoi Festivals across Japan were instigated by the success of the Kochi-city Yosakoi Festival, started in 1953. The Yosakoi Festival has a carnival-like atmosphere with parades of dancers. The festival was organized by the Kochi Chamber of Commerce to beat the post-war recession and depression, and raise the morale of people (Mori, 1998). Inspired by Kochi Yosakoi’s success, one university student in Sapporo with volunteer students started Yosakoi Soran Festival in Sapporo in 1991. Their own festival committees, comprised of volunteers, run both festivals today in Kochi and Sapporo. The Yosakoi Festival is spreading across Japan (Yonehara, 2002; Yosanet, 2007). Another example is the Inagé Kumin Matsuri (Inagé Ward Festival) started in 1993 when the City of Chiba was divided into six wards. In order to raise solidarity among community members in the ward, the Inagé ward started a festival. This festival was initiated by government offices (city and the ward) (Hasegawa, 2002). Many peripheral towns are applying for a license to brew Doburoku and organize Doburoku festivals as part of community development projects. The total number of designated Doburoku special areas is 69, and these require extensive government intervention and regional initiatives for differentiation as a tourist event (Toyoyoshi, 2006).

Although many event-style festivals are emerging, equally a large number of newly created festivals are disappearing due to the financial burdens and resource shortage in continuing the events (Hasegawa, 2002). As the number of events all over Japan is reaching a saturation point, people have a choice and events that are more attractive win the visitors. In the remote areas where the ageing of residents and depopulation of the communities are major issues, communities are launching various events and festivals as a means of rescuing otherwise ‘dying communities’. With limited resources, these community development projects focus on local assets, including regional cuisine as a feature attraction, combined with activities that take advantage of local natural resources.

Regional Food Today Across Japan

Bell and Valentine (1997) define that the ‘region’ is a product of ‘a natural landscape and a peopled landscape’ (p. 153). What people consider or imagine as a regional food may not necessarily reflect reality. Bell and Valentine (1997) use the example of Yorkshire pudding and how outsiders’ stereotype image of Yorkshire pudding differs from what insiders consider as Yorkshire pudding. Avieli (2005) also emphasizes that the ethnic and regional food are often imagined or invented. Nonetheless the topic of regional dishes is emotionally loaded and sparks regional pride and identity.

Until the railways and road systems connected the remotest parts of Japan, many villages were isolated and developed their own dishes with limited local produce. The mountainous physical features separated one hamlet from another hamlet. Microclimates created by these physical features also differentiated available produce and foodstuff between neighbouring villages. Even if the communities produced the same product, for instance, miso (soy bean paste), the quality of water, the quality of soy beans, the type of fermentation agents used and the type of soil soy beans grow in distinguish the type and taste of the end-product, miso paste. The closest comparison is the concept of ‘terroir’ often discussed with wine.

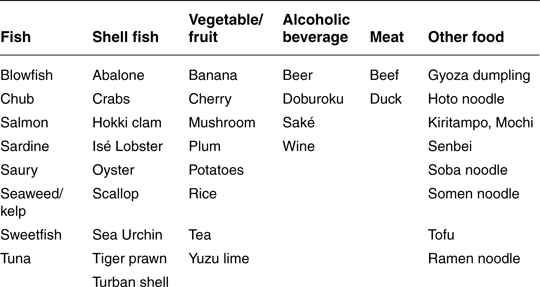

The list of the regional food shown in Table 15.1 was compiled by Rokugo Junior High School students. There is a Shokuiku (Food Education) movement today to preserve traditional food ways and Japanese education institutions include a curriculum of understanding regional cuisine. In the Rokugo project, each region’s regional government offices or tourism offices nominated the region’s most well-known or typical dishes as their ‘regional dish’. With such emic pre-sentation of regional dishes, most of the dishes are so-called traditional dishes and not been invented with modern ingredients. Most of the places use rice and cereal, vegetables, and fish (fresh water or sea). Occasionally a special type of sushi is shown as a regional dish. Two exceptions are Hokkaido and Okinawa. Genghis Khan (Mongolian-style barbeque) represents Hokkaido, owing to Japan’s colonization of Hokkaido Island with animal husbandry as a new form of farming in the late nineteenth century (MAFF, 2005d; Hokkaido Kinen-hi Risuto, 2006). Native Ainu dishes use salmon, venison, seal, and dried vegetables and herbs (Haguma, 2002). Okinawa, as a tropical island with a challenge of keeping ingredients fresh, had developed famous pork dishes. The traditional Okinawan formal dishes were developed to entertain Chinese ambassadors since 1400 AD, thus there is a strong Chinese influence on ingredients and cooking techniques (Okinawa Prefectural Government, 2003).

The traditional regional dishes do attract people from outside the region to some degree, particularly when the main ingredient of the dish is unique to the region. For example, oysters are cultivated from Hokkaido to Kyushu; however, Hiroshima prefecture produces more than 71 per cent of the entire oysters harvested in Japan (Yamada, 2002). Therefore, the Hiroshima oyster is best known and its festival draws more visitors than other regions’ oyster festivals. One notable point is that the advertisement of food festivals emphasizes the regional ingredients, yet the known regional dishes, which are made from featured ingredients, are less visible in the advertisement.

Food and Festivals in Japan

The provision of food and drink is an important part of festivals and entertainment. Many festivals feature ‘food’ or ‘drink’ as the main attractions. Depending on the type of festivals, the type of food or drink provided varies. Some festival food used in rituals at shrines are often not the main attraction and they can be a very humble snack such as édamamé (green soybeans), surumé (dried squid), and grilled chicken (Ashkenazi, 1993). Other festivals such as the Haboro Sea Urchin Festival features freshly harvested sea urchins as well as other seafood dishes (Haboro TV, 2007).

People travelling a significant distance to visit a food festival is a relatively new phenomenon. Until the late nineteenth century, only pilgrims and accidental travellers who happened to be at the right place at the right time had a precious chance to enjoy dishes from outside their own residential region. During the Meiji Era (1869–1912), the railway system spread nationwide. The boxed lunch (ekiben) sold at various railway stations were invented based on local food. However, both railway travel and purchasing of ekiben were privileges of a handful of elite for nearly 70 years. It was not until after the post-war economic recovery in 1956 when these ekiben began to sell regional dishes at various price ranges to accommodate an assortment of customers (Ekiben no Komado, 2007). Although the common people’s exposure to regional dishes were relatively early with the development of the ekiben, the concept of visiting a food festival outside their own hometown has only been seen in the past few decades. The origin of food festival tours is uncertain; one of the biggest Japanese tour operators suspects the origin was rather hap-hazardous off-season tour packages whose attraction was a regional dish beginning in the 1970s and 1980s (Personal communication, 2007).

With information technology today, it is very easy to find the list of events in Japan. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs supports Web-Japan (http://web-japan.org/atlas/festivals/festi_fr.html), which includes a list of selected events and festivals. Japan Travel Bureau has a web site that can be searched for events as well, and the event search web site (Rurubu.com) has over 130 food events throughout the year listed. Although many events and festivals are on search engines, smaller events and festivals or those in smaller communities are often overlooked in the large database. Each community has its own web site these days or a group of communities share a site. A small but attractive tourist town of Hagi, for example, is not found on any Search Engine’s event list, yet it shows its festivals and events for the forthcoming 2 months, along with its culinary traditions and attractions on its own web site (http://city.Hagi.yamaguchi.jp/portal/taberu.sakana/index.html).

Food Festival Seasons

Selected featured items of the festivals from across Japan are shown in Table 15.2. These featured items are taken from the descriptions of event lists (Rurubu.com, JTB, various prefectures’ event lists). Each category includes explicitly identified varieties and excludes the entries that simply describe ‘fish’, ‘aquaculture products’, or ‘agriculture products’. The list is not exhaustive, yet gives some idea what types of food (food ingredients) are popular as feature items for festivals. Fresh ingredients such as fish and fruit are advertised as ‘catch it yourself’/‘pick your own’, ‘eat fresh’, ‘cooked according to local recipes’, and ‘buy and send home by a special delivery service’. Tea and rice products from the first harvest of the year are associated with dedication ritual to local shrines. These main items are usually accompanied by other food products, which are also unique to the area.

Table 15.2 Selected feature items of food festivals

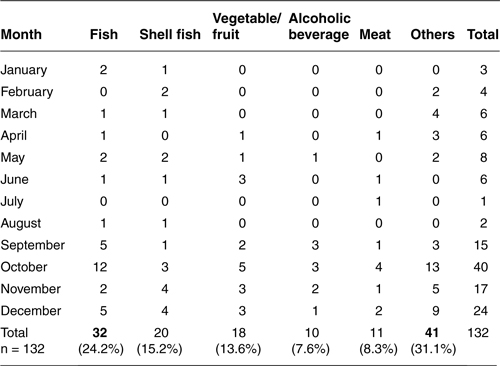

As shown in Table 15.3, the featured food items of the festivals vary from month to month. The number of festivals is also surprisingly concentrated in October (30 per cent of entire festivals). Autumn is obviously the season of harvest and as the Japanese saying goes ‘appetizing autumn (shokuyoku no aki)’, eating becomes a focus in this season. Popular seafood festivals (24.2 per cent of entire festivals) are spread through September to December. The festivals that feature fresh seafood are determined by the permitted fishing seasons and vary by species. Rainy seasons (May to June in Okinawa; June to July in the rest except Hokkaido) and a hot and humid summer challenge food safety and hygiene at outdoor festivals.

Table 15.3 Features of the events by months

Notes: Fish category includes: fish varieties and sea weed varieties. Shellfish category includes: shellfish, lobster/shrimp varieties, and sea urchin. Vegetable/fruit category includes: vegetable, fruit, tea, and rice. Meat category includes: meat, poultry, and dairy products. Others category includes: prepared products (e.g. noodles, soup, rice cakes, tofu, sweets, etc.) or combination of different categories (no one main feature). Source: Rurubu.com (2006).

On the other hand, the geographical advantage of having a cold north to a warm south stretches the harvesting seasons, thereby extending festival season. Using the example of the oyster again, Japan boasts both winter and summer oyster seasons. There are over 25 varieties of oysters in Japan alone. Although in the western hemisphere, the known season for the oyster is from September to April. Southwestern Japan enjoys a warm sea temperature and the most popular variety, Magaki is in season from December to February (Komatsu, 2001); whilst northern Japan takes advantages of a cold sea temperature and the season is from October to March, but some varieties are in season in Summer (Okhotsk Sanchoku Asaichi, 2003). The well-known summer variety is natural iwagaki (rock oyster) from Tohoku, and is best between June and August (Shunshun-do, 2006). Although the possibility of purchasing the shun (in season) oysters stretches from October to August, the well-known oyster festivals start in October (Hokkaido), and the number of festivals peaks in November. Hiroshima particularly organizes a number of oyster festivals between November and March (Benride Gozaru, 2007) and ending in late May (Hokkaido) (Akkeshi Town, 2007).

Similar to the oyster, the sea urchin’s harvesting areas spread all over Japan, and so Sea Urchin festivals are also widespread. Over 100 varieties of sea urchin exist in Japan, nevertheless only 7 varieties are suitable for human consumption (Zenchinren, n.d.). Licensed harvesting seasons vary from one region to another and these staggered seasons allow for allyear-round availability of sea urchin for festivals. Fishing seasons vary by variety of the sea urchin. First, northern Okhotsk (from January), then Kyushu (from April) and then most of the regions start in July. Therefore, the Sea Urchin Festivals are usually in the month of July; Éhimé prefecture’s festivals are in September to October. These festivals are event-type festivals, started by local governments or tourism associations. The example of Akuné in the Kyushu area below represents different Sea Urchin Festivals.

The Akuné city government in Kagoshima in collaboration with Akuné Tourism Cooperation launched the Akuné Sea Urchin Bowl Festival in 2007 (Chiran, 2007). The restaurants have been independently hosting similar events in the past; however, this is one of the series of events the City of Akuné intended to establish its own ‘Community Development Through Food’ project (Chiran, 2007). In this festival, the feature is rice in a bowl covered with 100 grams of purple sea urchin (Akuné Kanko, 2007), Akuné harvests 370 tons of sea urchins per annum (MAFF, 2006). Taking an advantage of being in a warmer region, it hosts the festival from April to May (55 days).

Locations and Scales of Food Festivals

As mentioned above, while there is no comprehensive national listing of food and drink festivals, some selected festivals/events are available from the Internet and these have been used to generate Table 15.4. As shown in Table 15.4, Hokkaido and Tohoku areas in the north listed 37.5 per cent of total events, followed by 18.7 per cent in the Chubu area. It is not surprising as Japanese seafood-related festivals (fish and shell fish categories in Table 15.3 totalled to 39.4 per cent) in northern regions have a longer seafood season than southern regions. Warmer climates cannot retain the freshness of the ingredients for a long time. However, smaller communities simply did not participate in listing their events and festivals on the Internet or the sites were neglected by web owners. It also depends on the advertising budget of each community for each event and how many visitors the community can handle.

The scale of the festivals and events varies substantially. In Aomori prefecture, Hiranai town’s Hotate Matsuri (Scallop Festival) attracts more than 117,000 people for this 1-day event, which exceeds the town’s population of 14,500 (MAFF, 2006). Shirahige Shrine Doburoku festival in Ota village, Oita prefecture draws over 30,000 visitors over 2 days (Kitsuki City, 2007) and Ota village’s population is 1,794 (Wikipedia, 2007b); while the Soba Matsuri (buckwheat noodle festival) in Oita attracted 2,000 visitors (Bungotakada City, 2007a). As a comparison, when the focus of the event is other than food, the carnival-like street dancing Yosakoi Soran Festival in Hokkaido attracts over 40,000 participants (Yosanet, 2007) and a traditional Rice Planting Festival in Tashibunosho in Oita drew 500 visitors (Bungotakada City, 2007b).

While food and drink festivals such as seafood festivals are held all over Japan, other types of food festival are more spatially and temporally limited. For example, Yokohama city in Metropolitan Tokyo will celebrate its 150th year of the opening of Yokohama Harbour in 2009. As part of the 5-year celebration (2005–2009), there will be the annual ‘World Gourmet Festival’. The main theme is ‘jimoto shokuzai (Yokohama’s indigenous food ingredients)’. Within Yokohama city, participating restaurants and food suppliers are offering a variety of menus, using local ingredients. Occasionally food festivals from other regions are invited to Yokohama. Umaimono [Tasty Food] summit was held in Yokohama in 2007 and the main attraction was a food event called ‘Shoku no Jin [Battle of Food]’ from Niigata city. Niigata in northern Japan started this event in 1992, to introduce food ingredients and local dishes in Niigata. This event takes place throughout the year, and the biggest winter season (December to March) attracts over 170,000 visitors. Shoku no Jin in Yokohama limited the visitors to 20,000 over 2 days, yet the prepared food products were not enough in quantity to satisfy visitors (Niigata Shoku no Jin, 2007; Pacifico Yokohama, 2007). This type of ‘visiting’ food festivals are often seen as events in the department store or community programme. Department stores host food and drink festivals, highlighting products from across Japan or invite well-known restaurants to participate.

Challenges for Festivals in the Future

As the number of new food festivals increases, the challenges for the existing festivals are many. Once the festival is established and known, the organizers are divided by tasks, thus weaker communications among the divisions result and the cost of hosting the events including advertisement becomes more and more burdensome. Developing plans to make the festival more attractive without losing the core features is another concern.

Although not a food festival, the example of the Tanabata Festival in Shigehara, Chiba clearly shows some of these common dilemmas (Hirai, 2002). The Tanabata Festival originated in Chinese legend that a stellar princess and her mortal husband (Altair and Vega) meet once a year. It is celebrated on July 7th (or August 7th if the area follows the lunar calendar). In the city of Shigehara, shops on the street started a festival to attract visitors during low season in 1949. The street festival was very well received and the city and tourist association took over running the event in 1954. At the beginning, the festival hosted about 50,000 visitors over 3 days; around the year 2000, the visitor number increased to 850,000 people over 3 days. The cost of running this festival in 2000 was ¥32 million (approximately US $265,000 or €196,000). The city provides half the sum and sponsorship covers the other half. Approximately ¥5 million was spent on advertising, yet a researcher investigating the change in the festival over time (Hirai, 2002) and who was a resident of the city was unaware of the festival’s advertisement activities. The current challenge is that the festival is becoming humdrum and repetitive; small shops are moving out as a wave of large-scale shops in suburban areas are threatening business. Finding funding for the Festival costs is also becoming increasingly harder. The city is hoping that this Festival will involve not only visitors from outside, but also more citizens (participation as well as volunteering) in the near future.

Another example of the challenges is the modification of local festivals when it is re-created as an event. Otake (2002) examined authenticity, aging population, and the changing nature of bureaucracy in terms of how festivals are changing to larger events. The local people considered these events as different from their own festivals: the events attracts a large number of visitors, and therefore the informality and spontaneity of the festival was lost and instead, it is structured and orchestrated, the venue and the route of parades and dancing are fixed, and the type of ‘festival’ food has changed. Tourists demand cleanliness and comfort when attending these events, therefore modern substitutes for old traditional equipments are needed (e.g. tourists complain about the old-fashioned fishing boat for Awamori wine drinking as ‘dirty’ or ‘dingy’). The second point was related to the ageing population in the area in the context of maintaining or participating in the events. Japan’s youth population (from 0 to 24 years of age) is continually decreasing. In 2000, the youth accounted for 27 per cent of the total population and they show quite different cultural values and interests (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2000). In terms of passing down the history and heritage through festivals, the prospect is bleak. Otake’s third finding was with respect to the bureaucracy of regional government employees who are responsible for running these event-type festivals. The person(s) in charge of the festivals will stay in the post for a short time (e.g. 5 years) and their aim is to run the festivals every year without deficits. No innovation, remodelling or changes for better or worse are welcomed. In Japan, there is a saying that the nail that sticks out gets pounded back in, so there is reluctance to make significant changes.

Food Festivals and Regional Identity: Concluding Remarks

Food and drink are important parts of entertainment in Japan, especially at festivals. Geographical attributes and the historical evolution of regional cuisine helped in the formation of regional identity; and vice versa, regional identify and pride helped further sophisticate regional cuisines. Yet, regional cuisine only became more widely known through two very recent developments. The nationwide railway system spreads regional cuisine across Japan through the ekiben lunch box, and the Japanese people have become affluent enough to pursue the pleasure of ‘food and drink’. As a reaction to rather humble food practice at home, Japanese consider pursuing gastronomic pleasure in a Haré environment something of importance.

The timing was right for the growth of festivals as the average Japanese became wealthy enough to travel around; interests in gourmet food was heightened; and food safety improved at the same time the health of the population faced a new challenge from a more westernized diet. Japanese food festivals today are mostly re-created events. The reasons and motivations behind re-creating these food events are manifold. It is political, it is socio-cultural, and it is economic.

The resurgence of food festivals is political because the Government of Japan feels the urgency of protecting disappearing knowledge and techniques in traditional food ways. It is also concerned about educating younger generations about nutrition, reaffirming a relationship between food production and consumption, and establishing a relationship between health and good eating habits. The Government has on its agenda that the declining primary industry must be protected for the saké of food safety and self-sufficiency. Food events are one of the best ways to promote this political agenda.

The resurgence is also socio-cultural. After a long history, the Japanese established a well-balanced Japanese-style diet, which has nearly been overturned by globalization and western-style convenient food in the last three decades. The Japanese society became excessively affluent and many people pursue the epicurean pleasure of gastronomy. Food is no longer a sustenance of life, but something to indulge one’s life in. In another light, for small communities in remote areas, events focused on regional food and unique foodstuffs will put the community on the map. This, consequently, increases the self-esteem, self-efficacy, and pride of the local community population.

Finally, the resurgence of food festivals is economic. Many food festivals emerged in order to rejuvenate a community’s economic activities. With various government laws and initiatives, there are a wide range of seed grants and technical support available for communities to start festival projects. Food festivals also lead to potential trade after the events between suppliers and consumers. Japanese household’s spending on food and food-related expenses are steadily increasing even after the prolonged economic recession. These trends will enhance the potential of food festivals as an economic engine.

The issues the food festivals themselves face can also be looked at in terms of political, socio-cultural, and economic dimensions. It is political because when political priorities shift, there is no guarantee that the projects through Omatsuri Law (Law Concerning the Promotion of Sightseeing and Commerce and Industry in Designated Areas by Organizing Events Taking Advantage of Traditional Music, Arts and Other Local Cultures) will be supported as much as today. Government officials who are involved in the community projects are usually apathetic and avoid all possible risks of failure. Moreover their involvement in the projects are of a limited term. The socio-cultural challenge is related to the lack of the next generation who are willing to continue traditions. The older generations are ageing and soon will be unable to continue to be involved in the community festivals. Consumer’s tastes are also changing over time. How long the food events with the same food products can survive is another challenge. The economic challenge is finding grants and funds to continue and maintain the community events. Food events often require additional activities to keep the visitors in the area.

This chapter has attempted to illustrate the importance of understanding the role of geography, and history in the development of regional identity and cuisines. These form the basis of food and drink festivals in Japan, many of which are undergoing transformations to staged events with the assistance of some government support. While small rural community festivals are very important and hold potential for rural tourism, the changing demographics and social attitudes place some of these festivals at risk over the long term.

References

Akkeshi Town (2007). Dai 58 kai Akkeshi Sakura/Kaki Matsuri [The 58th Akkeshi town cherry blossom and oyster festival]. Retrieved from http://info.town.akkeshi.hokkaido.jp/pubsys/public/mu1/bin/view.rbz?cd=584

Akuné Kanko (2007). Akuné Uni-matsuri Kaisai [Akuné Sea Urchin Festival is coming]. Retrieved from http://www.kagoshima-mall.co.jp/akune-kanko/pickup.php

Ashkenazi, M. (1993). Matsuri: Festivals of a Japanese Town. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

Avieli, N. (2005). Roasted pigs and bao dumplings: Festive food and imagined transnational identity in Chinese – Vietnamese festivals. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 46(3), 281–293.

Bell, D. and Valentine, G. (1997). Consuming Geographies: We Are Where We Eat. Routledge, London.

Benride Gozaru (2007). Hiroshima no Kaki Matsuri [Oyster Festivals in Hiroshima]. Retrieved from http://benride.gozaru.jp/kaki.html

Bungotakada City (2007a). Kyo no Dekigoto: Soba Matsuri Daiseikyo [Today’s event: Buckwheat noodle festival a big success]. Retrieved from http://www.city.bungotakada.oita.jp/dekigoto/bungotakadasobamatsuri.jsp

Bungotakada City (2007b). Shoen no Sato, Tashibono Sho: Otaue Sai [Tashibono-sho, the manor land: the Rice Planting Festival]. Retrieved from http://www.city.bungotakada.oita.jp/nourin-suisan/tashibunosyou/tasibunosyou_otaue.jsp

Chiran, T. (2007). Akuné de Hatsu no Unidon Matsuri [The first Sea Urchin Bowl Festival in Akuné] (2007/03/19). Japan Alternative News for Justice and New Cultures. Retrieved from http://www.janjan.jp/area/0703/0703181873/1.php

Dokkyo University (1998). Images of Japan: Nipponjin no Shokuseikatu. Retrieved from http:www2.dokkyo.cajp/~japan/Japanese/sub4.htm

Ekiben no Komado (2007). Ekiben Gakushu Shitsu [Ekiben study room]. Retrieved from http://www.ekibento.jp/

Food Kingdom Miyagi (2007). Miyagi, Daté-ké to Shokubunka [Food culture of the Daté Family in Miyagi]: Miyagi-ken Norinsuisan-bu Shoku-sangyo Shinko-ka [Food Industry Promotion Section, Department of Agriculture, Fishery and Forestry, Miyagi prefecture]. Retrieved from http://www.foodkingdom-miyagi.jp/date/index.shtml

Fuji Television, (2000). Iron Chef: The Official Book, edited by the Staff of Iron Chef, Translated by Kaoru Hoketsu. Berkley Books, New York.

Fujigoko (2007). Hibino kurashi to Matsuri – Minzoku –: it [sic] deifies with a daily life – Folk Customs –. Retrieved from http://www.fujigoko.co.jp/yoshida/history/folk.html

Haboro T.V. (2007). Event. Retrieved from http://www.haboro.tv/top.html

Haguma, K. (2002). Ainu Ryori Repooto [Report on Ainu dishes]. Retrieved from http://kotahaguma.hp.infoseek.co.jp/ainuCook.htm

Haitani K. (1996). Japanese Law Names. E-Asia, University of Oregon. Retrieved from http://purl.library.uoregon.edu/e-asia/ebooks/read/jpnlawnames.pdf.

Hasegawa, K. (2002). Matsuri: Ibento-gata to Dento-gata [Festivals: Event style vs. traditional style]. 2002nendo Shakaigaku Jisshu Hokokusho, Dai 4Sho: Matsuri [2002 Sociology Field Work Reports, Section 4: Festivals]. Retrieved from http://www.l.chiba-u.ac.jp/~sociology/dep/research/2002/2002report/data/sa02.pdf

Hirai, T. (2002). Maturi no Hensen – sigehara no tanabata matsuri – ibento-teki mature kara dento-teki matsui [Evolution of festival – Shigehara Tanabata Festival – from event-style festival to traditional-style festival]. 2002nendo Shakaigaku Jisshu Hokokusho, Dai 4Sho: Matsuri [2002 Sociology Field Work Reports, Section 4: Festivals]. Retrieved from http://www.l.chiba-u.ac.jp/~sociology/dep/research/2002/2002report/data/sa04.pdf

Hokkaido Kinenhi Risuto (2006). Hokkaido no Mukashi [Old times in Hokkaido]. Retrieved from http://www.geocities.jp/xxreport/html/theme_h1.html

Inoue, K. (2007). Shirochizu [Blank map]. Retrieved from http://www.freemap.jp/php/japan_nurinuri_1_1/japan_nurinuri.html

Kitsuki City (2007). Hirahige Tahara Jinja no Doburoku Matsuri. Retrieved from http://www.city.kitsuki.lg.jp/modules/itemmanager/index.php?like=0&level=4&genreid=8&itemid=172&storyid=71

Komatsu, H. (2001). Iyo-iyo Shun no Kaki, Oishiku tabete, Kokoromo Karadamo Genki ni [Finally oyster season; enjoy oyster and keep your mind and body healthy]. Retrieved from http://www.kireine.net/tokusyu/toku0058/body.html

Machida (2002). Haré to Ké ni tsuite [About ‘festive’ and ‘ordinary’ ] (2002/9/9.) Retrieved from http://www7.plala.or.jp/machikun/kokoroto6.htm

MAFF (2005a). Waga Kuni no Shoku Seikatsu no Genjou to Shokuiku no Suishin ni Tuite [The reality of national food life and recommendation of food education]. Retrieved from http://www.maff.go.jp/syokuiku/kikakubukai.pdf

MAFF (2005b). Chisan Chisho Suishin Keikaku [Plans for implementing ‘locally grown, locally consumed’ movement]. Retrieved from http://www.maff.go.jp/chisanchisyo/jissen_plan.html

MAFF (2005c). Iikoto Ippaosi Chisan Chisho (Video clip). Retrieved from http://www2.maff.go.jp/cgi-bin/maff-tv/tv.cgi?ch=6&ptr=0&play=192&player=

MAFF (2005d). Komakonai Yousui no Chichi, Edwin Dun. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery of Japan: Digital Museum of Agricultural Water, Soil and Rural in Japan. Retrieved from http://www.maff.go.jp/nouson/sekkei/midori-ijin/01hkd/01hkd.htm

MAFF (2006). Waga Machi, Waga Mura – Shichouson no Sugata–[My city, my village in statistics]. Retrieved from http://www.toukei.maff.go.jp/shityoson/index.html

MAFF (n.d.). What is ‘Shokuiku (Food Education)’ ? Retrieved from http://www.maff.go.jp/english_p/shokuiku.pdf

Makino, T. (2007). Tabemono Bunka Ko: ‘Hare’ no hi no shokutaku [Thinking food culture: Food on a festive day]. Retrieved from http://www.jia-tokai.org/sibu/architect/2007/01/tabemono.htm

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (2000). Heisei 12-nen do Waga Kuni no Bunkyo Shisaku [Year 2000 National Policies on Education and Culture]. Retrieved from http://www.mext.go.jp/b-menu/hakusho/html/hpad200001

Mori, T. (1998). Yosakoi Festival in Kochi. Retrieved from http://www.yosakoi.com/jp/AboutYosakoi.html

Niigata Shoku no Jin (2007). Niigata Shokuno-Jin [Battle of food]. Retrieved from http://www.shokuno-jin.com/index.html

Okhotsk Sanchoku Asaichi (2003). Ima ga Shun no Shokuzai [Food ingredients in season]. Retrieved from http://asaichi.org/01syun/imasyun.html

Okinawa Prefectural Government (2003). Okinawa Cuisine. Retrieved from http://www.wonder-okinawa.jp/026/

Onshindo Pharmacy (2007). Food and Culture No. 3. Retrieved from http:ww7.tiki.ne.jp/~onshin/food13.htm

Origuchi, S. (2004). Ho to suru hanashi: Matrsuri no hassei sono ichi [Stories of heart: Origins of festivals, No. 1]. Reconstructed from Kodai-kenkyu Minzokugaku hen Dai ichi [Anthropology Volume 1] (1929) and Origuchi Shinobu Zenshu 2 [Shinobu Origuchi Anthology Volume 2] (1995) for Internet Library Aozora. Retrieved from http://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000933/files/13213_14433.html

Otake, Y. (2002). Matsurino Chuukaisha no Nayami [Dilemma of festival intermediaries]. 2002nendo Shakaigaku Jisshu Hokokusho, Dai 4Sho: Matsuri [2002 Sociology Field Work Reports, Section 4: Festivals]. Retrieved from http://www.l.chiba-u.ac.jp/~sociology/dep/research/2002/2002report/data/sa05.pdf

OVOP (n.d.). Oita OVOP International Exchange Promotion Committee. Retrieved from http://www.ovop.jp/jp/index.html

Pacifico Yokohama (2007). Umaimono Samitto [Tasty Food Summit]. Retrieved from http://www.pacifico.co.jp/information/archives/information_070201_umaimonosummit.pdf

Plam Record (2002). Yosakoi Soran towa [What is Yosako Soran?]. Retrieved from http://www.plamrec.com/yosakoidans2.htm

Rurubu.com (2006). Nippon no ibento sahchi [Event search in Japan]. Retrieved from http://www.rurubu.com/event/list.asp

Satomi, M. (2005). Niigata no Doburoku 7-shu o nomi kurabe [Tasting seven Doburoku varieties from Niigata] Dancyu 02.03.2005. Issue No. 11. Retrieved from http://www.president.co.jp/dan/special/sake/011.html

Segawa, K. (2001). Shokuseikatsu no rekishi [History of food-ways]. Kodansha, Tokyo.

Shigeto (2005). Shoku kiten ni Hito no arikata made [From food as a starting point to people’s ways of existence]. Kagawa daigaku meiyo kyoju yamano yoshimasa ‘Chokubunka to oishisa o kangaeru’ semina [Seminar on Food Way and Tastiness by Prof. Emeritus Yoshimasa Yamano, Kagawa University] (27.01.2005). Retrieved from http://www.palge.com/news/h17/1/seminar20050128.htm

Shunshun-do (2006). Shonau no Ten-nen Iwagaki wa Natsu ga Shun [Natural rock oyster from Shonai is Best in Summer]. Retrieved from http://www.ekamo.com/goods/fish/kaki.html

Slow Food Japan (2007). SFJ ni tsuite [About us]. Retrieved from http://www.slowfoodjapan.net/about_us/story.html

Sushi Master (2000). Sushi towa? Sushi no rekishi [What is sushi? The History of Sushi]. Retrieved from http://sushi-master.com/jpn/whatis/history.html

Suzuki, T. (2003). Amerika Komugi Senryaku to Nipponjin no Shoku Seikatsu [America’s Wheat Strategies and Japanese Food Life]. Fujiwara-shoten, Tokyo.

Toshi Noson Gyoson Koryu Kasseika Kikou (2007). ‘Gyojishoku tte nandarou [What is event food?]’. Noson Asbi-gaku Nyumon: Chiiki ni nezashita shoku-bunka [Introduction to farming village leisure study: Food culture rooted to the area]. Retrieved from http://www.kouryu.or.jp/asobi/2003syoku/d/2.htm

Toyoyoshi, H. (2006). Hitoaji chigau Naruko: Doburoku senryaklu jimono no aji, shokuno hashirani [Different Naruko: Doburoku strategy and local cuisine as a culinary pillar]. The Sankei Shinbun Web-site (12.09.2006). Retrieved from http://www.sankei.co.jp/chiho/tohoku/061209/thk06120900.htm

Wikipedia (2007a). Sushi. Retrieved from http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AF%BF%E5%8F%B8

Wikipedia (2007b). Ota-mura. Retrieved from http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E7%94%B0%E6%9D%91

Yamada (2002). Oister [sic]. Kagawa Nutrition University Bunka-happyokai 2002 (Takahashi Katsumi Seminar). Retrieved from http://www.eiyo.ac.jp/bunkahappyou/happyou2002/H14HP/tka2/frame.htm

Yonehara, K. (2002). Matsuri-en ga dekirutoki–‘Yosakoi’ o toshite [When a festival is born]. 2002nendo Shakaigaku Jisshu Hokokusho, Dai 4Sho: Matsuri [2002 Sociology Field Work Reports, Section 4: Festivals]. Retrieved from http://www.l.chiba-u.ac.jp/~sociology/dep/research/2002/2002report/data/sa03.pdf

Yosanet (2007). Yosakoi Soran Matsuri 16th in Sapporo: History. Retrieved from http://www.yosanet.com/yosakoi/history/outline.php

Zenchinren (n.d.). Zenkoku Chinmi Shoukougyo Kyodo Kumiai Rengokai [United Alliance of National Delicacy Business Cooperations]. Retrieved from http://www.chinmi.org/

Zenkoku Joho Gakushu Shinko Kyokai (n.d.). Shokumotsu no Rekishi [History of food]. Retrieved from http://www.shikakunavi.net/kids/gika/shokumotu1.html.