SECOND WATCH 1 P. M. SEXT

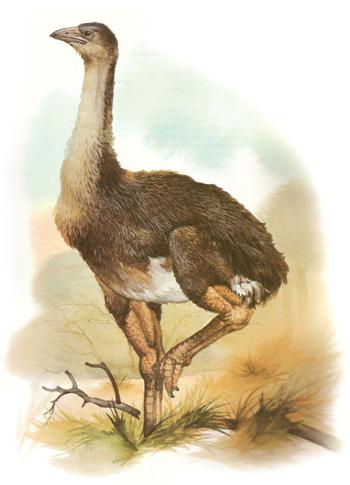

GIANT MOA – 1850 – Dinornis maximus

Joel S. Polack – 1838

History of New Zealand

Among the Maori there were traditions of supernatural beings in the form of birds, having waylaid native travellers, among the forest wilds, vanquishing them with an overpowering strength, killing and devouring them. The traditions are reported with an air of belief that carries conviction.

New Zealand was an island-world that was a time-capsule of the planet forty million years ago. It was a world inhabited primarily by birds; except for bats, there were no mammals (not even marsupials) in New Zealand until the legendary arrival of the Great Fleet of the Polynesian Maoris, about 1300 AD. The first European to “discover” these islands was Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642, who named it after the small island of Zealand in Holland. However, the extreme hostility of the warlike Maoris prevented further incursions by Europeans until the arrival of Captain James Cook’s ship Endeavour in 1769. Three years later, a French expedition arrived in the Bay of Islands, but rapidly withdrew after the Maoris killed and ate 27 of its officers and men. Among those suffering this fate was the expedition’s commander, Captain Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, after whom Mauritius’ Marion’s Tortoise was named.

Although both the British and French expeditions recorded hundreds of new species, the Giant Moas were not among them. Joel S. Polack’s account is the first published acknowledgement of the existence of these giant birds. Polack was a trader in New Zealand between 1834 and 1837. In 1838, Polack published his two-volume History of New Zealand, in which he said he had found bones of a large ostrich-like bird, and added that the Maori claimed that in times not long past “very large birds existed, but the scarcity of animal food, as well as the easy method of entrapping them, has caused their extermination.”

Reverend William Williams – 1839

Williams’ Journal

, Cloudy Bay, New Zealand

The natives there had mentioned to an Englishman of a whaling party that there was a bird of extraordinary size to be seen only at night on the side of a hill near there; and that he, with the native and a second Englishman, went to the spot; that after waiting some time they saw the creature at some little distance, which they describe as being fourteen or sixteen feet high. One of the men proposed to go nearer and shoot, but his companion was so exceedingly terrified, or perhaps both of them, that they were satisfied with looking at him, when in a little time he took alarm and strode up the mountain.

The Reverend William Williams was a Protestant missionary to the Bay of Islands in New Zealand who had translated the New Testament into Maori. Williams also compiled a Maori-English dictionary and built the first church in Poverty Bay. In the summer of 1838, Williams spent many months travelling in the East Cape district of the North Island (with another amateur naturalist, and printer, William Colenso) and recorded this incident near Waipapu.

In 1839 a traveller named John Rule obtained a 10-inch section of thigh bone of some huge creature in New Zealand and brought it back to Britain. He gave the bone to Richard Owen, an authority on prehistoric animals and the man who coined the word “Dinosaur.” The bone was so massive that it looked like an ox’s thigh bone. Owen initially thought this was a joke, but further examination convinced him that this was the leg bone of an unknown giant ostrich-like bird. In November 1839, Owen delivered a lecture to the Zoological Society of London in which he boldly asserted that New Zealand was once inhabited by an undiscovered species, a giant flightless bird.

Remarkably, only weeks after Owen’s prophetic lecture, a shipment of Moa bones collected by the Reverend William Williams and fellow missionary the Reverend Richard Taylor reached England. These bones immediately confirmed Owen’s analysis and made him famous overnight. Owen gained royal recognition and became one of the chief forces behind the creation of the British Natural History Museum at South Kensington.

William Colenso – 1842

Journal of Natural History,

New Zealand

I heard from the natives of a certain monstrous animal; while some said it was a bird, and others a person, all agreed that it was called a Moa; and that in general appearance it somewhat resembled an immense domestic cock, with the difference, however, that if anyone ventured to approach the dwelling of this wonderful creature, he would be invariably trampled on and killed by it.

In 1841, William Colenso returned to New Zealand to search for more Moa relics. He went down the east coast of the North Island, asking Maoris to help him find evidence of these birds. He recovered five Moa thigh bones and a large number of Maori myths about these great birds and returned with them to Britain in 1842. Colenso was the first to record the name “Moa,” although there is some evidence to suggest the authentic Maori name may have been “Tarepo.”

In 1844, the British Governor FitzRoy spoke with an 85-year-old Maori named Haumatangi who claimed to remember the second visit of Captain Cook in 1773, and stated that the last Moa in his part of New Zealand had been seen two years before Cook’s arrival. Another Maori, Kawana Papai, said he had himself taken part in Moa hunts when he was a boy about 1790. He said the birds were rounded up and killed with spears. He claimed they were dangerous to hunt, as the Moa defended itself fiercely with vigorous kicks; but as they had to stand on one leg to kick, Maori hunters would strike at the supporting leg and bring it to ground.

Excavations of other early tribal settlements have uncovered charred Moa bones and Moa eggs utilized as water bottles by native peoples. And in 1859, miners made the remarkable discovery of a Maori tomb containing a skeleton of a chieftain placed in a sitting position with its skeletal hands clutching a large Moa egg measuring 10 inches by 7 inches. Later still, in 1939 – a century after the first European acknowledgement of these semi-mythical birds – excavations by New Zealanders Roger Duff and Robert Falla in Pyramid Valley on the South Island resulted in the discovery of over 140 complete skeletons of six distinct Moa species.

Reverend Richard Taylor, M. A., F. G.

S – 1855

Te Ika A Mauri – New Zealand and Its Inhabitants

Of all the birds that have once existed in New Zealand, by far the most remarkable is the Moa. Perhaps it is the largest bird which ever had existence, at least during the more recent period of the earth’s history; and it is by no means certain that it is even now extinct! I first discovered its remains in 1839, at Tauronga, and now Waipau. These bones were of recent but undeterminable age. However, Mr Meurant, employed by the Government as Native interpreter, stated to me that in the latter end of 1823, he saw the flesh of the Moa in Molyneux harbour; since that period, he has seen feathers of the same bird in the Native’s hair. They were a black or dark colour, with purple edge, having quills like those of the Albatross in size, but much coarser. He saw a Moa bone which reached four inches above his hip from the ground and as thick as his knee, with flesh and sinews upon it. The flesh looked like beef. The slaves who were from the interior, said that it was still to be found inland. A man named George Pauley, now living in Fareaux Straits told him he had seen the Moa, which he described as being an immense monster, standing about twenty feet high. He saw it near a lake in the interior. It ran from him and he also from it. He saw its footmarks before he came to the river Tairi, and the mountains.

The Reverend Richard Taylor arrived as a missionary on the East Coast and the Bay of Islands in New Zealand with the Reverend William Williams. When Taylor made the voyage to England with the manuscript of his history of New Zealand in 1855, he brought with him the Maori Chief Hoani Wiremu Hipango and gained an audience with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Over the next decade, Sir Richard Owen classified, reconstructed, and named many of the Moa species. Owen gave these giant birds a scientific name to match their size: Dinornis or “Terror Bird” – which is comparable to his name for prehistoric reptiles: “Dinosaur” or “Terror Lizard.” He named six of the dozen species now known. These were: Dinornis robustus, D. elephantopus, D. crassus, D. giganteus and D. gracilis (i.e., robust, elephant-footed, fat, giant, and slender Moa). Finally there was the Dinornis maximus – the Giant Moa measuring 12 to 14 feet tall and a quarter ton in weight. This was taller than the Aepyornis maximus of Madagascar, but at a quarter ton, only about half the weight of the Elephant Bird.

THE EXCAVATION

Giant Moa – 1850

The earth is pulled up like a coffin lid

Bones like unstrung bows

And a battlefield of broken spearshafts

Giant shin bones cracked

Like diviners’ yarrow stalks

Beaks like shattered spearheads

The hexagrams of this dry graveyard swamp

I saw the broad clawed footprint

Of the giant bird in clay

Beneath the hump of the hill

That shadows the valley

Later we found a ring of Moa skulls

With a hunched chieftain’s skeleton at its centre

Clutched in his spidery grip:

A great Moa egg

Like the dragon pearl

That is the Maori moon

Sap of the veronica wood

They called “Moa’s blood”

They roasted Moa flesh on its fires

When an enemy was defiant at the death

They called him “fierce as the Moa”

And when the white man came

And the Maoris fell

When pestilence and war broke them

And all their world was ending

They cried out, “Ka ngaro I te ngaro a te Moa”

Alas, we are “lost as the Moa is lost”

In this valley I am shaken

By a vision rising

Like the dragon pearl moon

Eclipsing, for a dark hour

The bright noonday sun