FIRST WATCH 6 P. M. VESPERS

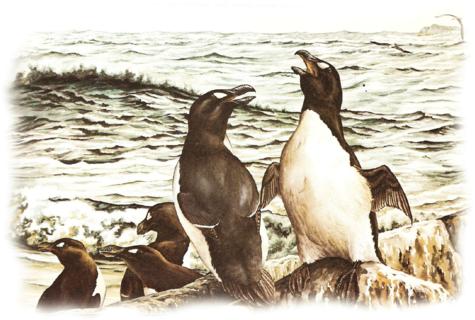

GREAT AUK OR GAREFOWL – 1844

Alca (Pinguinus) impennis

Jacques Cartier – 1534

Journals of Jacques Cartier,

Isle of Birds, Newfoundland

Some of these birds are as large as geese, being black and white with a beak like a crow’s. They are always in the water, not being able to fly in the air, inasmuch as they have only small wings about the size of half one’s hand, yet they move as quickly along the water as other birds fly through the air. And these birds are so fat that it is marvellous. In less than an hour we filled two boats full of them, as if they had been stones, so that besides them which we did eat fresh, each of our ships did powder and salt five or six barrels of them.

Jacques Cartier’s account of this unequal meeting of Great Auk and Man on the Isle of Birds (Funk Island) off the coast of Newfoundland in 1534 is the first written record of Europeans hunting these birds in North America: “And on the twenty-first of the said month of May we set forth from this [Catalina] harbour with a west wind, and sailed north, northeast of Cape Bonavista as far as the Isle of Birds, which island was completely surrounded and encompassed by a cordon of loose ice, split up into cakes. In spite of this belt of ice our two longboats were sent off to the island to procure some of the birds, whose numbers are so great as to be incredible, unless one has seen them; for although the island is about a league in circumference, it is so exceedingly full that one would think they had been stowed there. In the air and round about are an hundred times as many more as on the island itself.”

A curious theory links the Great Auk with the discovery of North America. It proposes that the Icelandic Vikings, already familiar with Auks and aware in a general sense of bird migrations, would have noticed the seasonal disappearances and departures of vast rafts of birds in their western waters. It would have been a small step for the Vikings to conclude that these Garefowl were travelling to other, similar islands in the west. Consequently, it has been suggested they could have followed the migrating legions of Auks, who would have led them first to Iceland, and later to Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Great Auk was the strongest and swiftest of northern swimming and diving birds, and almost immune to marine predators; while its rocky nesting sites in the rough North Atlantic were for millions of years inaccessible to men. It numbered in the tens of millions until recent historic times.

Anthonie Parkhurst – 1578

Hakluyt’s Voyages,

Isle of Penguins, Newfoundland

There are sea Gulls, Murres, Duckes, wild Geese, and many other kind of birdes store, too long to write, especially on one island named Penguin, where we may drive them on a planke into our ship as many as shall take her. These birds are also called, Penguins and cannot flie; there is more meate in one of these then in a goose; the Frenchmen that fish neere the grand baie, doe bring small store of flesh with them, but victuall themselves always with these birdes.

Cartier’s “Isle of Birds” of 1534, Parkhurst’s “Isle of Penguins” of 1578, and Cartwright’s “Funk Island” in 1792 are one and the same rookery visited by all three voyagers, and by countless others over nearly three centuries. The summer – the nesting season – was the only time that Great Auks could be taken, for the rest of the year they dispersed and lived at sea, where they were safe from human hunters. So each summer, the men came to their rookeries and set up camps where they waited for the birds to come to them. Stone corrals were constructed on the islets, and the birds were driven into them and slaughtered.

Slaying the Auks during the nesting season compounded the destruction; as did egg collection, as each nesting pair only produced a single egg. This slaughter and depredation continued unabated for nearly three centuries. The general presumption of most observers was summed up in one hunter’s account written in 1622: “God made the innocence of so poor a creature to become such an admirable instrument for the sustentation of man.”

By the Vikings, this bird was known as the Geirfugl. And by the Irish it was known as Gearrabhul – meaning “the strong stout bird with the spot” – which was corrupted through usage to “Garefowl.” Among the Welsh, who once hunted the bird on islets off Britain’s shores, they were called Pingouins, which means “white head.” The Great Auk was the original “Penguin: ” the “penguins” of the southern hemisphere having derived their name from British explorers who presumed these flightless Antarctic birds were a southern variety of the North Atlantic bird.

George Cartwright – 1792

Journal of Transactions and Events,

Funk Island, Newfoundland

Innumerable flocks of sea-fowl breed upon this isle every summer, which are of great service to the poor inhabitants of Fogo when the water is smooth, they make their shallop fast to the shore, lay their gang-boards from the gunwale of the boat to the rocks, and then drive as many penguins on board, as she will hold: for, the wings of those birds being short, they cannot fly, nor escape. The birds which people bring thence, they salt and eat, in lieu of salt pork.

Fishermen and Newfoundland colonists flocked to these rookeries every nesting season to kill birds and steal eggs. Also, many new industrial uses were found for these birds: feather beds, meat for bait, oil for lighting lamps, oil for fuel for stoves, and collar bones for fish hooks; and dried Auks (full of oil) were used as torches. The annual wholesale gathering of eggs was an especially destructive practice. Just one vessel commanded by a Captain Mood took 100,000 eggs in a single day.

By 1810 Funk Island was the only West Atlantic rookery left, and these constant summer raids by oil and feather merchants’ crews soon finished off even this last vast North American nesting site as well. The only place Great Auks existed after Funk Island rookery’s demise was a group of islands on the southwestern tip of Iceland. Most Auks withdrew to a lonely outcropping of rock called Geirfuglasker, or “Auk Rocks” – which was a lonely and dangerous outcropping of rock so rugged, it was safe from all but the most determined and foolhardy of hunters.

In 1830, the already near-extinct species suffered a further cataclysmic disaster. A volcano erupted under the sea near Iceland and caused a seaquake that resulted in the destruction of Geirfugl Island. The last rookery of the Great Auk sank beneath the sea, and the colony was destroyed and scattered.

It became apparent that about 60 Great Auks survived the sinking of Geirfuglasker. These birds took refuge on an even smaller and equally dangerous rocky outcrop, known as Eldey Island. It is from this last station that nearly all of the skins and eggs now found in European collections have been obtained, and during the fourteen years (1830-1844) that the Garefowl frequented this rock, one bird after another was hunted down for museum bounties, until there were just two left.

Professor A. Newton – 1861

The Last Garefowl Hunt – 4 June 1844,

Eldey Island, Iceland

As the three men leapt from the boat and clambered up on the rocks they saw two Garefowls sitting among numberless other rock-birds, and at once gave chase. The Garefowls showed not the slightest disposition to repel the invaders, but immediately ran along under the high cliff, their heads erect, their little wings somewhat extended. They uttered no cry of alarm, and moved with their short steps, about as quickly as a man could walk. Jon Brandsson, with outstretched arms, drove one into a corner, where he soon had it fast. Sigurdr Islefsson and Ketil Ketilsson pursued the second, and the former seized it close to the edge of the rock, here risen to a precipice some fathoms high, the water being directly below it. Ketil then returned to the sloping shelf whence the birds had started, and saw an egg lying on the lava slab, which he knew to be a Garefowl’s. He took it up, but finding it was broken, put it down again. All this took place in much less time than it takes to tell it.

Newton gives this account as being recorded in 1861, just 14 years after the event of the slaying of this last pair of Great Auks on the Icelandic skerry of Eldey. Another oral account confirms that Brandsson and Islefsson each killed a bird, but Ketilsson, frustrated at returning empty-handed, smashed the last intact egg with his boot. A third account, by James Wolley, was published in Ibis in 1861: “The capture of these two birds was effected through the efforts of an expedition of fourteen men, led by Vilhjaimur Hakonarsson; but only three were able to land on the rock, and they at great risk, namely, Sigurdr Islefsson, Ketil Ketilsson, and Jon Brandsson. Only two Great Auks were seen, and both were taken – Jon capturing one, and Sigurdr the other. It appears that this event took place between the 2nd and 5th June 1844. It appears that this expedition was undertaken at the instigation of Herr Carl Siemsen, who was anxious to obtain the specimens… the birds were sold for eighty rigsbank-dollars, or about £9.”

It is notably ironic that Great Auk relics have continued to appreciate in value over the years since its extinction. In 1934, in the midst of the Depression, one stuffed Great Auk sold for nearly $5,000, or five years’ wages for a fisherman; and a single egg for two years’ wages. Then, on 4 March 1971, the Icelandic Natural History Museum paid £9,000 for a single mounted specimen of a Great Auk.

ALPHA AND OMEGA

Great Auk or Garefowl – 1844

In the year 1844, Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Stood on the iron deck of the first transatlantic passenger liner

As the age of sail gave way to the age of steam

In that year, Samuel Morse

Sent a coded message singing through the steel lines

And electric relays of America’s first telegraph

Its chosen path was alongside the railway line

Between Baltimore and Washington

The message was biblical and portentous

It read: “What hath God wrought?”

In the year 1844, three daring men climbed

Up a precarious chimney of volcanic rock

In the wave lashed North Atlantic

Here the last lonely pair of Great Auks

Were chased down and slaughtered

Their last egg crushed

This too heralded the birth of our modern age

“What hath God wrought?”