FIRST WATCH 12 P. M. MIDNIGHT

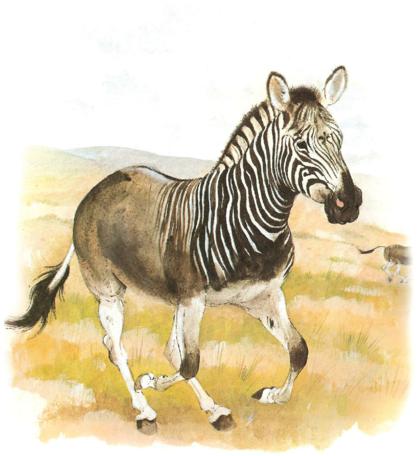

QUAGGA – 1883 – Equus quagga quagga

George Edwards – 1758

Gleanings of Natural History,

London

This curious animal was brought alive, together with the male, from the Cape of Good Hope: the male dying before they arrived at London, I did not see it; but this female lived several years at a house of his Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales, at Kew. The noise it made was much different from that of an ass, resembling more the confused barking of a mastiff-dog. It seemed to be savage and fierce in nature: no one would venture to approach it, and could not mount on its back. I saw it eat a large paper of tobacco, paper and all; and I was told, it would eat flesh, or any kind of food they would give it. I suppose that proceeding from necessity, or habit, in its long sea voyage; for it undoubtedly feeds naturally much as other horses and asses do, I mean on vegetables.

George Edwards was an aristocratic artist-naturalist who recorded the arrival of this first Quagga to reach Britain from the Cape of Good Hope. On the recommendation of Sir Hans Sloane, Edwards had been appointed the librarian of the Royal College of Physicians. Besides Gleanings, Edwards also published his earlier History of Birds, in which he described and illustrated more than 600 species never before described or delineated. He was later to become known as the “Father of British Ornithology.”

The Quagga was often mistaken for some sort of cross-bred animal: half-zebra, half-horse. It was, in fact, a distinctive type of Zebra. Its head and forequarters were striped like a zebra while its hindquarters were a solid rufous brown. Alternatively, the Edwards animal was for a time believed to be the female variation of the fully striped white-legged Burchell’s Cape Zebra. In fact, Burchell’s Zebra (Equus quagga burchelli) is now classified as a subspecies of the nominate Quagga species (Equus quagga quagga) and both suffered the same fate.

Zebras from “Ethiopia” were known to the Romans when the historian Dio Casio described them as “horses of the sun resembling tigers.” However, it was William Dampier, the famous adventurer and buccaneer, who, upon visiting the Dutch Colony of the Cape of Good Hope in 1691, first gave a description of Burchell’s Cape Zebra: “a very beautiful sort of wild ass whose body is curiously striped with equal lists of white and black.”

William John Burchell – 1811

Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa

, London

I could compare the clatter of their hooves to nothing but to the din of a tremendous charge of cavalry, or rushing of a mighty tempest. I could not estimate the accumulated number at less than fifteen thousand, a great extent of the country being actually chequered black and white with their congregated masses. As the panic caused by the report of our rifles extended, clouds of dust hovered over them, and the long necks of troops of ostriches were also to be seen, towering above the heads of their less gigantic neighbours, and sailing past with astonishing rapidity. Groups of purple Sassaybes and brilliant red and yellow Hartebeests likewise lent aid to complete the picture, which must have been seen to be properly understood, and which beggars all attempt at description.

William John Burchell was a remarkable English explorer and naturalist who from 1810-15 gathered over 50,000 specimens in the most extensive collection of African plant and animal species ever amassed – before or since. From 1825-30, he made a similarly extraordinary collection in Brazil which included 16,000 insects, and 1,000 animals. As an authority of Southern Africa – having travelled over 7,000 kilometres of largely unexplored territory – Burchell was instrumental in the parliamentary decision in favour of British emigration to the Cape in 1820. In later years much angered by disputes with the British Museum, and feeling unappreciated after having totally exhausted his own personal fortune in creating these astounding collections, Burchell took his own life in 1863.

The “purpleSassaybes” andthe “redHartebeests” colourfullydescribed by Burchell in his Travels as part of these vast herds of Quaggas and Burchell’s Zebras were sadly also all hunted to extinction. Sassaby was the Saan Bushmen’s name for a “goat-horned” antelope with a blue-grey coat that the Boers called Blaauwbok and the English called Blue Buck (Hippotragus leucophaeus). Burchell’s “red Hartebeest” was the nominate Cape Red Hartebeest (Alcelaphus caama caama).

The remarkable and unique Blue Buck was actually the first African animal to become extinct in historic times: the last specimen being shot about eighty years after its discovery by Europeans in 1799. By the 1830’s, all of the Cape Red Hartebeest herds had been reduced to a handful of animals that were kept in a private reserve until they too were killed off by poachers by 1940.

Jared Diamond – 1997

Guns, Germs, and Steel,

New York

“Efforts at domestication of zebras went as far as hitching them to carts: they were tried out as draft animals in 19th century South Africa. Alas zebras become impossibly dangerous as they grow older. Zebras have the unpleasant habit of biting a person and not letting go. They thereby injure even more American zoo-keepers each year than do tigers. Zebras are also virtually impossible to lasso with a rope because of their unfailing ability to watch the rope noose fly toward them and then to duck their head out of the way. Hence it has rarely (if ever) been possible to saddle or ride a zebra, and South Africans’ enthusiasm for their domestication waned.”

In England in the 1830’s there was a brief vogue for Quaggas as harness animals after Sheriff Parkins became famous in London society for his pair of exotic imports. A few decades later, Lord Rothschild rode in a carriage pulled by two Burchell’s Zebras. Eventually, however, both the Quagga and the Zebra proved to be too unpredictable. Quaggas in particular were prone to dangerous fits of rage. In 1860, the Regent’s Park Zoo’s only attempt to breed captive Quaggas failed when the stallion beat itself to death in its enclosure.

The last wild Quagga stallion was hunted down in the Cape in 1878; and the last captive Quagga died in the Artis Magistra Zoo in Amsterdam on the 12 August 1883. Only 23 specimens of the Quagga now exist in museums anywhere in the world.

Burchell’s Zebra, known to the Boers as the Bontequagga (meaning “painted Quagga”), managed to avoid extinction for a few decades longer than its cousin. The last known Bontequagga died in captivity in London’s Regent’s Park Zoo in 1910.

HORSES OF THE SUN

Quagga – 1883

1.

Bushmen called them Quay-Hay

In imitation of their “barking neigh”

Memories of them gather like thunderclouds

On the edge of this landscape of the mind:

A high veldt with kloofs and koppies

Where thoughts like strong winds gust

Through the tall grass, acacia

Whistling thorn and quiver trees

2.

Knowing they have no concept of heaven

Or hell or soul or resurrection

I summon them anyway

And for a moment, the gates are forced

By the rolling thunder of thousands

Upon thousands of pounding hooves

Legions of stallions and mares

Burst onto the veldt

“Horses of the sun resembling tigers”

According to Dio Cassio

Nostrils flared, “savage and fierce by nature”

Magnificent in their defiance

While the Boer hunters wait

Over water with long guns

3.

The Orion constellation

Is read differently here

Still the Celestial Hunter

But the sword is no sword

This one carries a spear

And the three stars

Of the belt are no belt

But three Quagga

The hunter’s prey

For millennia after stars have gone out

We still marvel at the beauty of their light

The brilliant memory of what once was