SECOND WATCH 1 A. M. MIDNIGHT

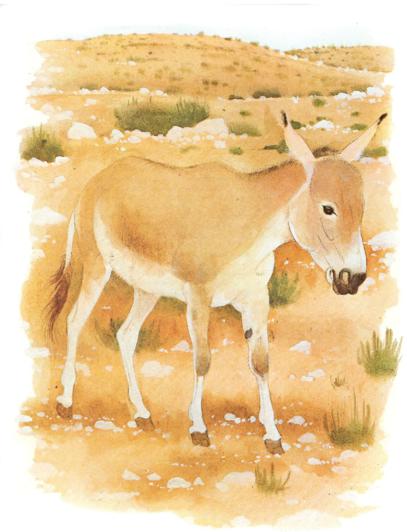

ASSYRIAN ONAGER – 1930 – Equus hemionus hemippus

Xenophon – 401 BC

Anabasis: The March of Cyrus,

Mesopotamia

Cyrus now advanced through Arabia, having the Euphrates on the right, five days’ march through the desert, a distance of thirty-five parasangs. In this region the ground was entirely a plain, level as the sea. There were wild animals, however, of various kinds; the most numerous were wild asses; there were also many ostriches, as well as bustards and antelopes; and these animals the horsemen of the army sometimes hunted. The wild asses, when any one pursued them, would start forward a considerable distance, and then stand still; and again, when the horse approached, they did the same; it was impossible to catch them, unless the horsemen, stationing themselves at intervals, kept up the pursuit with a succession of horses. The flesh of those that were taken resembled venison, but more tender.

Travelling through Mesopotamia in 1884, Canon Tristram wrote of the Assyrian Onager: “This is the Wild Ass of Scripture and the Ninevite sculptures mentioned by Strabo, Eratosthenes, Artemidorus, Homer, and Pliny. Measuring just one metre at the shoulder, it was the smallest and swiftest of all the horse family.”

Xenophon’s adventures are among the most famous in all of military history. He commanded an elite force of ten thousand Greek mercenary soldiers who supported Cyrus, a pretender to the throne of the Persian Empire. The Greeks completely routed the opposing army, but disastrously Cyrus was killed in the battle, so Xenophon’s Greeks had to fight their way over thousands of miles back to Greece.

Xenophon’s observations were precisely confirmed over twenty-two centuries later by the British explorer Blandford in 1876: “It is said the Onager can not be caught by a single horseman in the open. But at other times they are caught in relays of horsemen and greyhounds. Some say their meat is prized above all other venison.”

Sir Austen Layard – 1850

Nineveh and Its Remains

, Mesopotamia

A great herd of Wild Asses are seen in the Sinjar region west of Mosul. Those mentioned by Xenophon must have been seen in these very plains. The Arabs sometimes catch the foals during the spring, and bring them up with milk in their tents. They are of light fawn colour – almost pink. The Arabs still eat their flesh.

Sir Austen Layard’s remarkable travels to Mesopotamia were made expressly to uncover the lost civilizations of Assyria. He succeeded in discovering the lost cities of Nineveh and Nimrod, and the palaces of Ashurbanipal and Sennacherib. It was his knowledge of Xenophon and the Scriptures that led to his success. Here, while camped on the desolate site of ancient Nineveh, Layard remembers the biblical passages relating to wrath of Jehovah being unleashed upon Sennacherib and quotes Zephaniah (ii, 13-15): “And He will stretch out His Hand against the north, and destroy Assyria; and will make Nineveh a desolation, dry like a wilderness… a place for beasts to lie down in”: an accurate description of Assyria’s fate.

J. E. T. Aitchison – 1885

British Botanical Expedition

, Persia

My guide took me to a slight elevation, above the ‘Plain of Wild Asses’. For some time I could see nothing; at last whilst using my glasses, I noticed clouds of dust, like a line of smoke left in the track of steamers. These several lines of dust-cloud were caused by herds of Asses, galloping in various directions over the great plain. One herd came well within a mile’s distance; from its extent, I am even now of the opinion that the herd consisted of at least 1000 animals. I counted sixteen of these lines of dust-cloud at one time on the horizon.

J. E. T. Aitchison conducted botanical surveys of Persia and Afghanistan for the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew for Sir William Hooker. Wild Asses are of two distinct types: the African Wild Ass (Equus africanus), ancestor of the domestic donkey, and the irascible and never domesticated Asian Onager (Equus hemionus). Besides the Assyrian Onager of Syria and Mesopotamia there was one other subspecies in the Near East: the Persian Onager (Equus hemionus onager) – now critically endangered with only about 500 animals in two reserves in Iran. Aitchison’s account testifies to the immense numbers that, before the introduction of modern firearms, once inhabited these now nearly empty deserts.

William Ridgeway – 1905

Contributions to the Study of Equidae

, London

That the Onager was regularly captured and domesticated in Assyria in ancient times is clearly established by one of the bas-reliefs discovered by Sir Austen Layard at Nineveh. The relief, which is one of a series of slabs recording scenes in the life and hunting expeditions of Ashurbanipal (668-626 BC), represents two of the king’s attendants lassoing a wild ass. The other two asses are seen running away.

William Ridgeway is correct here. Sir Austen Layard was not only aware that he was following in the footsteps of Xenophon, but interestingly enough, this is the same animal Layard discovered precisely observed by a sculptor over 2400 years earlier in the royal hunt on the walls of Nineveh that he was in the process of excavating. And furthermore, besides the Onager, there are found the images of the Persian Lion and the Aurochs – all three suffering the same fate as the Assyrians.

Austen Layard later presented the British Museum – along with these massive relief wall sculptures of the royal hunt portraying the Assyrian Onager – a specimen of this same species: the only wild-caught example in any British collection.

This region of Old Mesopotamia between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers has been the setting for many other military adventures for over five thousand years. It has seen the rise and fall of the Sumerians, the Babylonians, the Hittites, the Assyrians, the Medes, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Mongols, the Turks, and the British. And Mosul seems to have been the seat of power for extravagantly ruthless dictators from the days of Sennacherib to those of Saddam Hussein.

Otto Antonius – 1938

On the Recent Equidae

, Vienna

The little Hemippus of Mesopotamia and Syria, domesticated by the ancient Sumers before the introduction of the horse became totally extinct in recent years. It could not resist the power of modern guns in the hands of the Anazeh and Shammar nomads, and its speed, great as it may have been, was not sufficient always to escape from the velocity of the modern motor car which more and more is replacing the Old Testament Camel-Caravan.

The social anthropologist Jared Diamond writes extensively about the how and why of the process of domestication of animals. He wonders why, out of the world’s 148 possible big wild herbivorous mammal candidates – although a number have been “tamed” – only a dozen have been successfully domesticated, and only six have been universally adopted: sheep, goat, pig, cow, horse, and donkey.

Interestingly enough, Diamond points out that, while there are eight distinctive species of wild equids (horses and relatives) that would all appear to be suitable candidates, only two of them – the Tarpan as the ancestor of the Horse and the North African Ass as the ancestor of the Donkey – were successfully domesticated. He then specifically observes the case of the Assyrian Onager. “Closely related to the North African ass is the Asiatic ass, also known as the Onager. Since its homeland includes the Fertile Crescent, the cradle of Western civilization and animal domestication, ancient peoples must have experimented extensively with onagers. We know from Sumerian and later depictions that onagers were regularly hunted, as well as captured and hybridized with donkeys and horses. Some ancient depictions of horse-like animals used for riding or for pulling carts may refer to onagers. However, all writers about them, from Romans to modern zookeepers, decry their irascible temper and their nasty habit of biting people. As a result, although similar in other respects to ancestral donkeys, onagers have never been domesticated.”

The last wild Assyrian Onager was shot in 1927 in Arabia, while the last captive animal died in the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna in 1930. This, despite the efforts of the Zoo’s director Otto Antonius, one of the co-founders of modern zoological biology, and one of the leading lights in the rescue of such endangered species as the Wisent.

THE WALLS OF NINEVEH*

Assyrian Onager – 1930

“Onagers are among the beasts of the royal hunt on the walls

of Ashurbanipal’s palace at Nineveh.” – Sir Austen Layard, 1850

1.

When those in the heavens

Had not been named

When those beneath the earth

Were without a name

We raced alive and free

With no need of names

The speeding world was turning

Beneath our bright hooves

As whirlwinds and sandstorms

Arose in our wake

And chased the sun’s fire

Across the desert sky

2.

Then later came those Others

With their names and words

With their dark incantations

And even darker spells

Building kingdoms and empires

By the power of words

With names to own and suppress

And spells to enslave

Mastering the art of slaughter

Made a paradise

Watered with the tears of slaves

And the blood of beasts

3.

In these passageways of word

And image cut in stone

In these corridors of power

In the great king’s house

With lion-slaying arrows

With axes and spears

With horse-slaves and chariots

The lord of the hunt reigns

Here we too are captives

In this counterfeit world

Where we forever flee

The king’s deadly wrath

4.

When shall we come back

From this eternal night?

When shall we come back

To the world of light?

When shall we come back

And these shackles sever?

When shall we come back

To our life forever?

Then with a voice like thunder

This dreadful wonder

Ends our soul’s endeavour

With its answer: “Never!”

* “The Walls of Nineveh” elegy is a curious literary exercise. It is an attempt at an ancient Sumerian verse stanza form. It may be the first new poem to be composed in this form in about three thousand years.