NEVERMORE: A Book of Hours has been conceived in the form of a twenty-four hour vigil. Each hour is dedicated to one now-vanished animal species. And each of these hourly meditations is divided into four parts: Illustration, Reportage, Commentary, and Elegy.

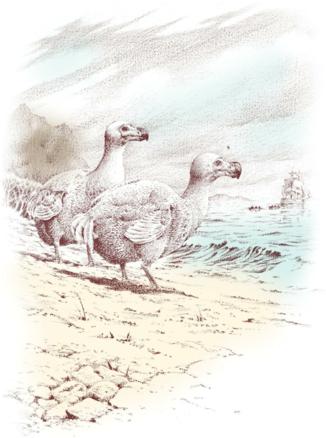

Illustration: an original commissioned portrait of each species by one of this book’s four distinguished wildlife artists: Tim Bramfitt, Peter Hayman, Mick Loates and Maurice Wilson.

Reportage: testimonies by witnesses – who were often the first (or last) to see these animals alive – in the form of monologues taken from naturalists’ journals, explorers’ ships’ logs, travellers’ memoirs.

Commentary: notations on the testimonies, the witnesses and the animal species which attempt to give them a scientific and historic context.

Elegy: original elegies composed in poetic conventions and forms related to each animal’s geographic and cultural environment.

In these epicedia, I am at one with Gary Snyder, who in his Turtle Island, wrote: “I am a poet who has preferred not to distinguish in poetry between nature and humanity.” In this book, human history and natural history are not separate disciplines: humans and animals share a common and interactive history.

Through the reportage and commentaries here, the reader will see how the fates of these animals are directly linked to individuals and events in human history: Julius Caesar with the Aurochs, Xenophon with the Assyrian Onager, Marco Polo with the Elephant Bird, Christopher Columbus with the Eskimo Curlew, Hernando Cortez with the American Bison, Jacques Cartier with the Great Auk, Samuel de Champlain with the Passenger Pigeon, Captain Cook with the Hawaiian O-O, Vitus Bering with Steller’s Sea Cow, Charles Darwin with the Antarctic Wolf-Fox.

In the reportage, I have extracted what might almost be seen as “prose poems” from the chronicles of historic witnesses because these authentic voices often convey that sense of the astonishment experienced in those first encounters with these newly discovered creatures; and – as often – a sense of pathos with their ultimate passing.

NEVERMORE: A Book of Hours is an adaptation of the Agrega, a Coptic – or Ancient Egyptian – word meaning “Book of Hours.” The Agrega is primarily used today by the Coptic Orthodox Church as a schedule for observing hours of prayer, instruction and meditation – and is comparable to the medieval Roman Catholic Horae, a Latin word meaning “Book of Hours.”

Books of Hours were the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscripts and personal devotional manuals. They were variable in content but all contained a schedule of hourly readings and prayers adopted from the daily rounds of monastic devotion known as the “canonical hours,” as well as being a calendar of prayers for saints and martyrs and a vigil for the souls of the dead.

In NEVERMORE: A Book of Hours, the day is divided into eight Coptic canonical hours, and each of these is divided into three watches. Each watch is then assigned an “animal martyr” as the focus of meditation in order to cover the full twenty-four hours of this vigil.

The Coptic Agrega was chosen in preference to the Latin Horae largely because the – now extinct – Coptic language is actually a demotic form of Egyptian hieroglyphics, and is linked to the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. These “coffin texts” used a similar structure of hours for the passage of the souls of the dead through the afterlife.

This book is a requiem to vanished animals which I have tracked down in the museums and institutes around the world. Over the years I have touched the Aurochs horn, the feathers of the Passenger Pigeon, the pelt of the Shamanu, and the amulet of the Dodo’s skull. I have seen mounted specimens and preserved skins of the Bali Tiger, the Tarpan and the Thylacine. I have observed trophy heads of the Barbary Lion, the Blue Buck and the Quagga. And I have been amazed by the gigantic thigh bones of the Moa, the massive rib cage of the 7-ton Steller’s Sea Cow, and the phenomenal two-gallon Elephant Bird egg.

These are now as much mythical animals as the dragon and the unicorn, but here I have attempted to give them a form of life in the only place they may now exist – the human imagination.