The Winds of Harmattan

Asuquo followed her nose and used her birdlike sense of direction. All around her were men selling yams and women selling cocoa yams. She always knew where to find the good ones; they had a starchier smell. Her mother didn’t believe her when she said she could smell specific vegetables in the market, but she could.

Asuquo was about to jostle past a slow-moving man carrying a bunch of plantains on his shoulder when an old woman grabbed one of her seven locks. The woman sat on a wooden stool, a pyramid of eggs on a straw mat at her feet. Next to her, a man was selling very dried-up-looking yams.

“Yes, mama?” Asuquo said. She did not know the woman, but she knew to always show respect to her elders. The woman smiled and let go of Asuquo’s hair.

“You like the sky, wind girl?” she asked.

Asuquo froze, feeling tears heat her eyes. How does she know? Asuquo thought. She will tell my mother. Asuquo’s strong sense of smell wasn’t the only thing her mother didn’t believe in, even when she saw it with her own eyes. Asuquo’s face still ached from the slap she’d received from her mother yesterday morning. But Asuquo couldn’t help what happened when she slept.

The man selling yams brushed past her to hand a buyer his change of several cowries. He looked at her and then sneezed. Asuquo frowned and the old woman laughed.

“Even your own father is probably allergic to you, wind girl,” she said in her phlegmy voice. Asuquo looked away, her hands fidgeting. “All except one. You watch for him. Don’t listen to what they all say. He’s your chi. All of your kind are born with one. You go out and find him.”

“How much for ten eggs?” a young woman asked, stepping up to the old woman.

“My chi?” Asuquo whispered, the old woman’s words bouncing about her mind. Asuquo didn’t move. She knew exactly whom the woman spoke of. Sometimes she dreamt about him. He could do what she could do. Maybe he could do it better.

“Give me five cowries,” the old woman said to her customer. She gave Asuquo a hard push back into the market crowd without a word and turned her attention to selling her eggs. Asuquo tried to look back, but there were too many people between her and the old woman now.

After she’d bought her yams, she didn’t bother going back to find the old woman. But from that day on, she watched the sky.

Asuquo was one of the last. It is whispered words, known as the “bush radio,” and the bitter grumblings of the trees that bring together her story. She was a Windseeker, one of the people who could fly, and a Windseeker’s life is dictated by more than the wind.

Eleven years later, the year of her twentieth birthday, the Harmattan Winds never came. Dry, dusty, and cool, these winds had formed over the Sahara and blown their fresh air all the way to the African coast from December to February since humans began walking the earth. Except for that year.

That year, the cycle was disrupted, old ways poisoned. This story will tell you why …

Asuquo was the fourth daughter of Chief Ibok’s third wife. Though she was not fat, she still possessed a sort of voluptuous beauty with her round hips and strong legs. But her hair crept down her back like ropes of black fungus. She was born this way, emerging from her mother’s womb with seven glistening locks of dada hair hanging from her head like seaweed. And women with dada hair were undesirable.

They were thought to be the children of Mami Wata, and the water deity always claimed her children eventually, be it through kidnapping or an early death. Such a woman was not a good investment in the future. Asuquo’s mother didn’t bother taking her to the fattening hut to be secluded for weeks, stuffed with pounded yam and dried chameleons, and circumcised with a sharp sliver of coconut shell.

Nevertheless, Asuquo was content in her village. She didn’t want to be bothered with all the preparations for marriage. She spent much of her time in the forest and rumors that she talked to the sky and did strange things with plants were not completely untrue.

Nor were the murmurs of her running about with several young men. When she was twelve, she discovered she had a taste for them. Nevertheless, the moment a young man from a nearby village named Okon saw her, standing behind her mother’s home, peeling bark from a tree and dropping it in her pocket, he fell madly in love. She’d been smiling at the tree, her teeth shiny white, her skin blue black and her callused hands long-fingered. When Okon approached her that day, she stood eye to eye with him, and he was tall himself.

Okon’s father almost didn’t allow him to marry her.

“How can you marry that kind of woman? She has never been to the fattening hut!” he’d bellowed. “She has dada hair! I’m telling you; she is a child of Mami Wata! She is likely to be barren!”

My father is right, Okon thought, Asuquo is unclean. But something about her made him love her. Okon was a stubborn young man. He was also smart. And so he continued nagging his father about Asuquo, while also assuring him that he would marry a second well-born wife soon afterwards. His father eventually gave in.

Asuquo did not want to marry Okon. Since the encounter with the strange old woman years ago, she had been watching the skies for her chi, her other half, the one she was supposed to go and find. She had been dreaming about her chi since she was six and every year the dreams grew more and more vivid.

She knew his voice, his smile and his dry leaf scent. Sometimes she’d even think she saw him in her peripheral vision. She could see that he was tall and dark like her and wore purple. But when she turned her head, he wasn’t there.

She would someday find him, or he would find her, the way a bird knows which way to migrate. But, at the time, he was not close, and he was not thinking about her much. He was somewhere trying to live his life, just as she was. All in due time.

Her parents, on the other hand, were so glad a man—any man—wanted to marry Asuquo that they ignored everything else. They ignored how she brought the wind with her wherever she went, her seven locks of thick hair bouncing against her back. And they certainly ignored the fact that, though she was shaky, she could fly a few inches off the ground when she really tried.

One day, Asuquo had floated to the hut’s ceiling to crush a large spider. Her mother happened to walk in. She took one look at Asuquo and quickly grabbed the basket she’d come for and left. She never mentioned it to Asuquo, nor the many other times she’d seen Asuquo levitate. Asuquo’s father was the same way.

“Mama, I shouldn’t marry him,” Asuquo said. “You know I shouldn’t.”

Her mother waved her hand at her words. And her father greedily held out his hands for the hefty dowry Okon paid to Asuquo’s family.

Somewhere in the back of her mind, she knew her duty as a woman. So, in the end, Asuquo agreed to the marriage, ignoring, denying and pushing away her thoughts and sightings of her chi. And Asuquo could not help but feel pleased at the satisfied look in her father’s eyes and the proud swell of her mother’s chest. For so long they had been looks of dismissal and shame.

The wedding was most peculiar. Five bulls and several goats were slaughtered. For a village where meat was only eaten on special occasions, this was wonderful. However, birds, large and small kept stealing hunks of the meat and mouthfuls of spicy rice from the feast. On top of that, high winds swept people’s clothes about during the ceremony. Asuquo laughed and laughed, her brightly colored lapa swirling about her ankles and the collarette of beads and cowry shells around her neck clicking. She knew several of the birds personally, especially the owl who took off with an entire goat leg.

After their wedding night, Asuquo knew Okon would not look at another woman. Once in their hut, Asuquo had undressed him and taken him in with her eyes for a long time. Then she nodded, satisfied with what she saw. Okon had strong, veined hands, rich brown skin and a long neck. That night, Asuquo had her way with him in ways that left his body tingling and sore and helpless, though she’d have preferred to be outside under the sky.

As he lay, exhausted, he told her that the women he’d slept with before had succumbed to him with sad faces and lain like fallen trees. Asuquo laughed and said, “It’s because those women felt as if they had lost their honor.” She smiled to herself thinking about all her other lovers and how none of them had behaved as if they were dead or fallen.

That morning, Okon learned exactly what kind of woman he had married. Asuquo was not beside him when he awoke. His eyes grew wide when he looked up.

“What is this!?” he screeched, trying to scramble out of bed and falling on the floor instead, his big left foot in the air. He quickly rolled to the side and knelt low, staring up at his wife, his mouth agape. Her green lapa and hair hung down, as she hovered horizontally above the bed. Okon noticed that there was something gentle about how she floated. He could feel a soft breeze circulating around her. He sniffed. It smelled like the arid winds during Harmattan. He sneezed three times and had to wipe his nose.

Asuquo slowly opened her eyes, awakened by Okon’s noise. She chuckled and softly floated back onto the bed. She felt particularly good because when she’d awoken, she hadn’t automatically fallen as she usually did.

That afternoon they had a long talk where Asuquo laughed and smiled and Okon mostly just stared at her and asked “Why” and “How?” Their discussion didn’t get beyond the obvious. But by nighttime, she had him forgetting that she, the woman he had just married, had the ability to fly.

For a while, it was as if Asuquo lived under a pleasantly overcast sky. Her dreams of her chi stopped, and she no longer glimpsed him in the corner of her eye. She wondered if the old woman had been wrong, because she was very happy with Okon.

She planted a garden behind their hut. When she was not cooking, washing, or sewing, she was in the garden, cultivating. There were many different types of plants, including sage, kola nut, wild yam root, parsley, garlic, pleurisy root, nettles, cayenne. She grew cassava melons, yam, cocoa yams, beans, and many, many flowers. She sold her produce at the market. She always came home with her money purse full of cowries. She liked to tie it around her waist because she enjoyed the rhythmic clinking it made as she walked.

When she became pregnant, she didn’t have to soak a bag of wheat or barley in her urine to know that she would give birth to a boy. But she knew if she did so, the bag of wheat would sprout and the bag of barley would remain dormant, a sure sign of a male child. The same went with her second pregnancy a year later. She loved her two babies, Hogan and Bassey, dearly, and her heart was full. For a while.

Okon was so in love with Asuquo that he quietly accepted the fact that she could fly. As long as the rest of the village doesn’t know, especially Father, what is the harm? he thought. He let her do whatever she wanted, providing that she maintained the house, cooked for him and warmed his bed at night.

He also enjoyed the company of Asuquo’s mother, who sometimes visited. Though she and Asuquo did not talk much, Asuquo’s mother and Okon laughed and conversed well into the night. Neither spoke of Asuquo’s flying ability.

Asuquo made plenty of money at the market. And when Okon came back from fishing, there was nothing he loved more than to watch his wife in her garden, his sons scrambling about her feet.

Regardless of their contentment, the village’s bush radio was alive with chatter, snaking its mischievous roots under their hut, its stems through their window, holding its flower to their lips like microphones, following Asuquo with the stealth of a grapevine. The bush radio thrived from the rain of gossip.

Women said that Asuquo worked juju on her husband to keep him from looking at any other woman. That she carried a purse around her waist hidden in her lapa that her husband could never touch. That she carried all sorts of strange things in it, like nails, her husband’s hair, dead lizards, odd stones, sugar, and salt. That there were also items folded, wrapped, tied, sewn into cloth in this purse. Had she not been born with the locked hair of a witch? they asked. And look at how wildly her garden grows in the back. And what are those useless plants she grows alongside her yams and cassava?

“When do you plan to do as you promised?” Okon’s father asked.

“When I am ready,” Okon said. “When, ah … when Hogan and Bassey are older.”

“Has that woman made you crazy?” his father asked. “What kind of household is this with just one wife? This kind of woman?”

“It is my house, Papa,” Okon said. He broke eye contact with his father. “And it is happy and productive. In time, I will get another woman. But not yet.”

The men often talked about Asuquo’s frequent disappearances into the forest and the way she was always climbing things.

“I often see her climbing her hut to go on the roof when her chickens fly up there,” one man said. “What is a woman doing climbing trees and roofs?”

“She moves about like a bird,” they said.

“Or bat,” one man said narrowing his eyes.

For a while, men quietly went about slapping at bats with switches when they could, waiting to see if Asuquo came out of her hut limping.

A long time ago, things would have been different for Asuquo. There was a time when Windseekers in the skies were as common as tree frogs in the trees. Then came the centuries of the foreigners with their huge boats, sweet words, weapons and chains. After that, Windseeker sightings grew scarce. Storytellers forgot much of the myth and magic of the past and turned what they remembered into evil, dark things. It was no surprise that the village was so resistant to Asuquo.

Both the men and women liked to talk about Hogan and Bassey. They couldn’t say that the two boys weren’t Okon’s children. Hogan looked like a miniature version of his father with his arrow-shaped nose and bushy eyebrows. And Bassey had his father’s careful mannerisms when he ate and crawled about the floor.

But people were very suspicious about how healthy the two little boys were. The boys consumed as much as any normal child of the village, eating little meat and much fruit. Hogan was more partial to udara fruits, while Bassey liked to slowly suck mangoes to the seed. Still, the shiny-skinned boys grew as if they ate goat meat every day. The villagers told each other, “She must be doing something to them. Something evil. No child should grow like that.”

“I see her coming from the forest some days,” one woman said. “She brings back oddly shaped fruits and roots to feed her children.” Once again, the word ‘witch’ was whispered, as discreet fingers pointed Asuquo’s way.

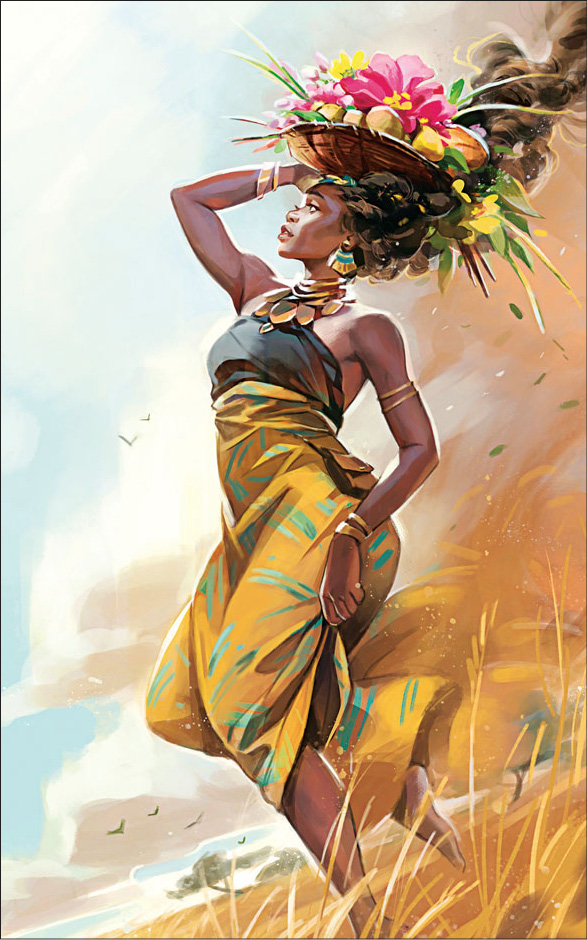

Illustration by Brittany Jackson

Regardless of the chatter, women often went to Asuquo when she was stooping over the plants in her garden. Their faces would be pleasant, and one would never guess that only an hour ago, they had spoken ill of the very woman from whom they sought help.

They would ask if she could spare a yam or some bitter leaf for egusi soup. But they really wanted to know if Asuquo could do something for a child who was coughing up mucus. Or if she could make something to soothe a husband’s toothache. Some wanted sweet-smelling oils to keep their skin soft in the sun. Others sought a reason why their healthy gardens had begun to wither after a fight with a friend.

“I’ll see what I can do,” Asuquo would answer, putting a hand on the woman’s back, escorting her inside. And she could always do something.

Asuquo was too preoccupied with her own issues to tune into the gossip of the bush radio.

She’d begun to feel the tug deep in the back of her throat again. He was close, her chi, her other half, the one who liked to wear purple. And as she was, he was all grown up, his thoughts now focused on her. At times she choked and hacked but the hook only dug deeper. When her sons were no longer crawling, she began to make trips to the forest more frequently, so that she could assuage her growing impatience. Once the path grew narrow and the sound of voices dwindled, she slowly took to the air.

Branches and leaves would slap her legs because she was too clumsy to maneuver around them. She could stay in the sky only for a few moments, then she would sink. But in those moments, she could feel him.

When her husband was out fishing and the throb of her menses kept her from spending much time in the garden, she filled a bowl with rainwater and sat on the floor, her eyes wide, staring into it as through a window to another world. Once in a while, she’d dip a finger in, creating expanding circles. She saw the blue sky, the trees waving back and forth with the breeze. It didn’t take long to find what she was looking for. He was far away, flying just above the tallest trees, his purple pants and caftan fluttering as he flew.

Afterwards, she took the bowl of water with her to the river and poured it over her head with a sigh. The water always tasted sweet and felt like the sun on her skin. Then she dove into the river and swam deep, imagining the water to be the sky and the sky to be the water.

Some nights she was so restless that she went to her garden and picked a blue passionflower. She ate it and when she slept, she dreamt of him. Though she could see him clearly, he was always too far for her to touch. She had started to call him the purple one. Aside from his purple attire, he wore cowry shells dangling from his ears and around his wrists and had a gold hoop in his wide nose. Her urge to go to him was almost unbearable.

As her mind became consumed with the purple one, her body was less and less interested in Okon. Their relationship quickly changed. Okon became a terrible beast fed by his own jealousy. He desperately appealed to Asuquo’s mother who, in turn, yelled at Asuquo’s distracted face.

Okon would angrily snatch the broom from Asuquo and sweep out the dry leaves that kept blowing into their home, sneezing as he did so. He tore through her garden with stamping feet and clenched fists, scratching himself on thorns and getting leaves stuck in his toenails. And his hands became heavy as bronze to her skin. He forbade her to fly, especially in the forest. Out of fear for her sons, she complied. But it did not stop there.

The rumors, mixed with jealousy, fear and suspicion spiraled into a raging storm, with Asuquo at the center. Her smile turned to a sad gaze as her mind continued to dwell on her chi that flew somewhere in the same skies she could no longer explore. Each night, her husband tied her to the bed where he made what he considered love to her body, for he still loved her. Each time, he fell asleep on top of her, not moving till morning when he sneezed himself awake.

Even her sons seemed to be growing allergic to Asuquo. She had to frequently wipe their noses when they sneezed. Sometimes they cried when she got too close. And they played outside more and more, preferring to help their father dry the fish he brought home, than their mother in the garden. Asuquo often cried about this in the garden when no one was around. Her sons were all she had.

One day, Okon fell sick. His forehead was hot but yet he shivered. He was weak and at times he yelled at phantoms he saw floating about the hut.

“Please, Asuquo, fly up to the ceiling,” he begged, grabbing her arm as he lay in bed, sweat beading his brow. “Tell them to leave!”

He pleaded with her to speak with the plants and mix a concoction foul-smelling enough to drive the apparitions away.

Asuquo looked at the sky, then at Okon, then at the sky. He’d die if she left him. She thought of her sons. The sound of their feet as they played outside soothed her soul. She looked at the sky again. She stood very still for several minutes. Then she turned from the door and went to Okon. When Okon gets well, she thought. I will take my sons with me, even if I cannot fly so well.

When he was too weak to chew his food, she chewed it first and then fed it to him. She plucked particular leaves and pounded bitter-smelling bark. She collected rainwater and washed him with it. And she frequently laid her hands on his chest and forehead. She often sent the boys out to prune her plants when she was with Okon in the bedroom. The care they took with the plants during this time made her want to kiss them over and over. But she did not because they would sneeze.

For this short time, she was happy. Okon was not able to tie her up and she was able to soothe his pain. She was also able to slip away once in a while and practice flying. Nonetheless, the moment Okon was able to stand up straight with no pain in his chest or dizziness, after five years of marriage, he went and brought several of his friends to the hut and pointed his finger at Asuquo.

“This woman tried to kill me,” he said, looking at Asuquo with disgust. He grabbed her wrists. “She is a witch! Ubio!”

“Ah,” one of his friends said, smiling. “You’ve finally woke up and seen your wife for what she really is.”

The others grunted in agreement, looking at Asuquo with a mixture of fear and hatred. Asuquo stared in complete shock at her husband whose life she had saved, her ears following her sons around the yard as they laughed and sculpted shapes from mud.

She wasn’t sure if she was seeing Okon for what he really was or what he had become. What she was sure of was that in that moment, something burst deep inside her, something that held the realization of her mistake at bay. She should have listened to the old woman; she should have listened to herself. If it weren’t for her sons, she’d have shot through the ceiling, into the sky, never to be seen again.

“Why … ?” was all she said.

Okon slapped her then, slapped her hard. Then he slapped her again. Only her chi could save her now.

Okon brought her before the Ekpo society. He tightly held the thick rope that he’d tied around her left wrist. Her shoulders were slumped, and her eyes were cast down. Villagers came out of their huts and gathered around the four old men sitting in chairs and the woman kneeling before them in the dirt.

Her sons, now only three and four years old, were taken to their aunt’s hut. Asuquo’s hair had grown several feet in length over the years. Now there were a few coils of grey around her forehead from the stress. The people stared at her locks with pinched faces as if they had never seen them before.

The Ekpo society’s job was to protect the village from thieves, murderers, cheats, and witchcraft. Nevertheless, even these old men had forgotten that once upon a long time ago, the sky was peopled with women and men just like Asuquo.

Centuries ago, the Ekpo society was close to the deities of the forest, exchanging words of wisdom, ideas and wishes with these benevolent beings who had a passing interest in the humans of the forest. But these days, the elders of the Ekpo society were in closer contact with the white men, choosing which wrongdoers to sell to them and bartering for the price.

Her husband stood behind her, his angry eyes cast to the ground. All this time he had let her go in and out of the house whenever she liked; he never asked where exactly she was going. He never asked who she was going to see. It couldn’t have just been the forest. He had asked many of the women who they thought the man or men she was being unfaithful with was. They all gave different names. Father warned me that she was unclean, he kept thinking.

The four old men sat on chairs, wearing matching blue and red lapas. Their feet close together, scowls on their faces. One of them raised his chin and spoke.

“You are accused of witchcraft,” he said, his voice shaky with age. “One woman said you gave her a drink for her husband’s sore tooth and all his teeth fell out. One man saw you turn into a bat. Many people in this village can attest to this. What do you have to say for yourself?”

Asuquo looked up at the men and for the first time, her ears ringing, her nostrils flaring, she felt rage, though not because of the accusations. It made her face ugly. The purple one was so close, and these people were not listening to her. They were in her way, blocking out the cool dusty wind with their noise.

Her hands clenched. Many of the people gathered looked away out of guilt. They knew their part in all of this. The chief’s wives, their arms around their chests, looked on, waiting and hoping to be rid of this woman who many said had bedded their husband numerous times.

“You see whatever you want to see,” she said through dry lips. “I’ve had enough. You can’t keep me from him.”

She heard her husband gasp behind her. If they had been at home, he’d have beaten her. Nevertheless, his blows no longer bothered her as much. These days her essence sought the sky. It was September. The Harmattan Winds would be upon the village soon, spraying dust onto the tree leaves and into their homes. She’d hold out her arms and let the dust devils twirl her around. Soon.

But she still couldn’t fly that well yet, especially with her shoulders weighed down by sadness. If only these people would get out of the way. Then she would take her sons where they would be safe, and the caretakers she chose would not tell them lies about her.

“Let the chop nut decide,” the fourth elder said, his eyes falling on Asuquo like charred pieces of wood. “In three days.”

She almost laughed despite herself. Asuquo knew the plant from which the chop nut grew. In the forest, the doomsday plant thrived during rainy season. Many times, she’d stopped to admire it. Its purplish bean-like flower was beautiful. When the flower fell off, a brown kidney-shaped pod replaced it. She could smell the six highly poisonous chop nuts inside the pod from meters away. Even the bush rats with their weak senses of smell and tough stomachs died minutes after eating it.

Asuquo looked up at the elders, one by one. She curled her lip and pointed at the elder who had spoken. She opened her mouth wide as if to curse them, but no sound came out. Then her eyes went blank again and her face relaxed. She mentally left her people and let her mind seek out the sky. Still a tear of deep sadness fell down her face.

The four elders stood up and walked into the forest where they said they would “consort with the old ones.”

Those three days were hazy and cold as the inside of a cloud. Okon tied Asuquo to the bed as before. He slept next to her, his arm around her waist. He bathed her, fed her and enjoyed her. In the mornings, he went to the garden and quietly cried for her. Then he cried for himself, for he could not pinpoint who his wife’s lover was. Every man in the village looked suspect.

Asuquo’s eyes remained distant. She no longer spoke to him, she did not even look at him, and she did not notice that her babies were not with her. Instead, she unfocused her eyes and let her mind float into the sky, coming back occasionally to command her body to inhale and exhale air.

Her chi joined her here, several hundred miles away from the village, a thousand feet into the sky. Now, he was close enough that for the first time, a part of them could be in the same place. Asuquo leaned against him as he took her locks into his hands and brought them to his face, inhaling her scent. He smelled like dry leaves and when he kissed her ears, Asuquo cried.

She wrapped her arms around him and laid her head on his chest until it was time to go. She knew he would continue making his way to her, though she told him it was too late. She’d underestimated the ugliness that had dug its roots underneath her village.

The elders came to Okon and Asuquo’s home, a procession of slapping sandals, much of the village following. People looked through windows and doorways, many milled about outside talking quietly, sucking their teeth and shaking their heads. Above, a storm pulled its clouds in to cover the sky. The elders came and her husband brought chairs for them.

“We have spoken with those of the bush,” one of them said. Then he turned around and a young man brought in the chop nut. Her husband and three men held her down as she struggled. Her eyes never met her husband’s. One man with jagged nails placed the chop nut in her mouth and a man smelling of palm oil roughly held her nose, forcing her to swallow. Then they let go and stepped back.

She wiped her nose and eyes, her lips pressed together. She got up and went to the window to look at the sky. The three young women and two young men watching through the window wordlessly stepped back with guilty looks, clearing her view of the gathering clouds. She braced her legs, willing her body to leave the ground. If she could get out the window into the clouds, she would be fine. She’d return for her sons once she had vomited up the chop nut.

But no matter how hard she tried, her body would only lift a centimeter off the ground. She was too tired. And she was growing more tired. Everyone around her was quiet, waiting for the verdict.

The rumble of thunder came from close by. She stood for as long as she could, a whole half hour. Until her insides began to burn. The fading light flowing through the window began to hurt her eyes. Then it dimmed. Then it hurt her eyes again. She could not tell if it was due to the chop nut or the approaching storm. The walls wavered and she could hear her heartbeat in her ears. It was slowing. She lay back on the bed, on top of the rope Okon had used to tie her down.

Soon she did not feel her legs and her arms hung at her sides. The room was silent, all eyes on her. Her bare breasts heaved, sweat trickling between them. Her mind passed her garden to her boys and landed on her chi. Her mind’s eye saw him floating in the sky, immobile, a frown on his face.

As the room dimmed and she left her body, he dropped from the sky only thirty miles south of Asuquo’s village of Old Calabar. As he dropped, he swore to the clouds that they would not see him for many many years. The wind outside wailed through the trees but within an hour it quickly died. The storm passed without sending down a single drop of rain to nurture the forest. No Harmattan Winds shook the trees that year. They had turned around, returning to the Sahara in disgust.

A year later, on the anniversary of Asuquo’s death, the winds returned, though not so strong. Reluctant. They have since resumed their normal pattern. Her husband, Okon went on to marry three wives and have many children. Asuquo’s young boys were raised calling his first wife “mother” and they didn’t remember the strange roots and fruits their real mother had brought from the forest that had made them strong.

As the years passed, when storytellers told of Asuquo’s tale, they changed her name to the male name of Ekong. They felt their audience responded better to male characters. And Ekong became a man who roamed the skies searching for men’s wives to snatch because he had died a lonely man and his soul was not at rest.

“There he is!” a boy would yell at the river, as the Harmattan Winds blew dry leaves about. All the girls would go splashing out of the water, screaming and laughing and hiding behind trees. Nobody wanted to get snatched by the “man who moved with the breeze.”

Nevertheless, it was well over a century before the winds blew with true fervor again. But that is another story.