‘SCHTOP, SCHTOP, SCHTOP!’ The short, plump man with closely cropped hair and a black shirt sounded as if he were auditioning for the lead role in a Dutch beer commercial. ‘Do you have no reshpecht? I cannot believe what I am seeing.’

What he was seeing was Roddy’s custom-made red and white Dario Pegoretti steel steed resting neatly against the front bumper of his matt black Range Rover.

‘Do you think this car was made to have a bike against it? It’sh fucking unbelievable that yoush can have no reshpecht like this.’ As he splenetically rumbled forth, his South-east Asian trophy wife stood in the background, more concerned with filing her nails than entering the fray. Roddy, meanwhile, was on the other side of the Château de Mazan car park, filling up his water bottles.

‘And schtill . . . none of you is moving the fucking bike,’ he continued, his voice getting higher and his face redder. ‘It’sh unbelievable! Schtop what you are doing and sort out this disreshpecht. Doesh my car look like a wall? Do I look like I don’t care a fuck?

‘Yesh, about time,’ Mr Grolsch said as Sam – the only one of our group not in stitches – liberated the car bumper from the heavy burden of the bike. The vehicle had a Swiss numberplate, which was odd because the guy didn’t sound Swiss, nor did he strike me as a purveyor of neutrality. ‘The funny thing,’ Sam told me as he pushed the bike away, ‘is that this is probably worth more money than his set of wheels.’

Without any attempt to smooth things over, the man and his lady friend (I reckon she had been hired for the weekend; surely no one would be married to such a specimen) got in the car and slammed the doors. Having driven to the exit, he realized that he needed to press a button to open the double gates. Rather sheepishly, he looked at me.

‘Unbelievable,’ I said. ‘Do I look like a porter?’ Before he could get away I offered up some friendly advice: ‘Schtop, schtop . . . You must do up your seat belt. Reshpecht the road!’

Roddy later admitted that he knew it was a mistake to rest his bespoke bike against the car – but part of me sensed that it was a subconscious decision to align something of extreme worth with something else in the same price bracket. My own scratched, muddy Felt frame leant against a soft pine bush, while the others had propped their bikes against the wall or our van. It seems logical that Roddy would have seen the pristine bumper of the scratch-less 4x4 and deemed it a worthy resting place for his pride and joy.

Like Melbourne John, Roddy also had an indirect link towards yours truly. It was while visiting friends in London earlier in the spring that he had picked up a copy of Cyclist and read the Last Gasp column where I sought out training tips from a personal coach. Off the back of the article, Roddy had contacted the same foul-mouthed London-based coach for advice on training out in Dubai. Together they came up with some kind of routine to get Roddy back into shape ahead of his week with us in the Alps – although this had been somewhat derailed by his demanding work schedule as a corporate lawyer, not to mention his living in a place where the only thing remotely resembling a hill was a man-made indoor ski park.

Although out of shape and slightly tubby (fair game for a man of 50), Roddy certainly looked the part. Besides his pristine Pegoretti and brand new race wheels, Roddy wore a pair of top-of-the-range cycling shoes in which he never took more than a couple of steps: as soon as he dismounted, they would be whipped off, leaving him to potter about in socks. Roddy was also a man of style, eschewing modern trade team jerseys and only sporting vintage classics from yesteryear: the iconic La Vie Claire kit in the Piet Mondrian-inspired rectangular red, blue, yellow and grey colour system, from the 1980s; a bright orange San Pellegrino jersey with a white sash; a black-and-white Carpano kit with the Italian flag. Judged on attire alone, Roddy was a Grand Tour winner (although Bob gave him a run for his dirhams with a limited-edition Black Dog outfit, including matching socks, which was unique in its peculiarity).

There’s a wonderful yet rather embarrassing series of photos of me posing with new boys John and Roddy at our coffee stop in Sault on the first official morning of the Alpine leg. Roddy stands (in his socks) on the right in his La Vie Claire get-up and full leg warmers (coming from Dubai, he suffered bitterly from the cold and was still recovering from a bout of flu, which may or may not have been an excuse for his constant strife in the saddle). John grins on the left in his replica Orica-GreenEdge kit from the Australian team’s first season back in 2012.

(In the short time I’ve been a rider I have always observed one rule: never wear the kit of a current professional cycling team. By decking himself out in the green, yellow and black of GreenEdge, John, bless him, allied himself to the portly chaps in full Team Sky garb doing laps of Richmond Park in London. Making matters worse, he still earnestly wore one of the long-since-parted yellow Livestrong bracelets so ubiquitous during Lance Armstrong’s duplicitous reign. Tut tut . . . Unless, of course, John was an unlikely master of irony.)

Finally, I’m standing in the middle, towering over both newcomers, my slim waist more or less in line with the top arc of their respective mini-paunches. I’m wearing a dark blue kit with pink, green and white horizontal stripes – an outfit designed by my photographer friend George, who has a side project producing his Ragpicker brand of cycling attire – stylish, but considerably cheaper, than the Rapha gear that adorns the shoulders of most fair-weather City-boy cyclists. Stuffed down my leg warmers are a couple of cubes of ice numbing both my sore knees. In my right hand is a can of iced tea. And pointing directly to said chilled beverage is . . . my willy. For yes, through the thin Lycra shorts you can see the (some would hopefully say generous) outline of my todger, standing to attention at around 10.30 a.m. The picture articulated the overriding problem with wearing bib shorts that are not black: they’re about as effective in covering up one’s trouser truncheon as a couple of strips of cling film.

Unintentional exhibitionism bore down on me for the entire duration of the tour. It led to the kind of constant stress that would have sent some professional sportsmen trotting home with their tail between their legs. There are few worse things than interacting all day with a bunch of people knowing that they can all see – and no doubt, behind your back, are speculating on the unfortunate visibility of – your privates. Worse still was the ‘performance-enhancing’ effect of such a phenomenon when played out inside my baggy lime green shorts. Like Harry Potter’s cloak, these shorts boasted powers of invisibility. Sadly, it was the shorts themselves that were near transparent, not their contents. They were exactly the kind of shorts I had feared others in our group might wear, and was grateful that they had not.

Whatever happens in later life, there’s a photo that Bob took of me from one of our opening days in Spain that will come back to haunt me. Shown on TV, the picture would have to appear after the watershed. Not content with displaying my flagrant groinal delineation (2 p.m. this time), the photo also showcases, right on the tip of the bendy bulge, a spot where the green of the shorts has become darker – the kind of spot that could well have been made by a post-urinary seepage of the sort whose absorption wouldn’t have showed up on black Lycra (the colour of choice for all sensible cyclists).

Photos of this ilk were regrettably two a penny, so to speak. Photoshop’s red-eye correction tool became the only possible, sadly retrospective, course of action. It was the male equivalent of being a lingerie model with a permanent case of camel toe. I felt solidarity with female celebrities caught, in flagrante delicto, exiting cars while flashing their undies, or worse. For something that was an all too apparent reminder of my manhood, it was curiously emasculating.

Taking up cycling had sadly seen off the days where my genitalia were my penetralia. I tried everything to combat this on-going budgie struggle. The uncomfortable ‘downward wrap’ approach; the ‘bundle it up in a ball’ tactic; the ‘straight up and pull the jersey down’ stratagem. None of them worked. In the end I had to resort to simply holding my hands or, better still, my helmet – my cycling helmet – in a position of diversional integrity.

Once, I brought up this little issue with Terry and he just laughed. ‘I would love to be in your position,’ he said. ‘Be proud. If you have it, flaunt it.’ Which is all very well until you hobble round a corner in your cleats and find yourself amid a group of children roughly waist height and then have to beg tacit forgiveness from their parents by a meek and apologetic look in your eye as the youngest of the kids – the one afraid of green snakes – starts to cry.

By any account, Monday mornings don’t get much better than a breezy ride along a vertiginous corniche overlooking a limestone canyon that the world seems to have forgotten. I thought of my friends back at home on their morning commute, at that moment possibly crammed into the Tube or taking on deadly HGVs and double-decker buses on Boris Bikes through central London. For me, the prospect of the working week as we set off from Mazan on the scenic road to Sault was an appealing one: my office would be the Alps and my desk a bicycle. There’d be no Prêt sandwich wolfed down for lunch while replying to emails and overdosing on the Mail Online’s sidebar of shame; instead there would be sizeable picnics overlooking cliffs and peaks and meadows, discussing the ocular fodder of the previous few hours while trying to ensure that my bib shorts didn’t ruin the appetite of my companions. Put simply: life was good and couldn’t have been further from the usual framework of busyness, deadlines, noise, crowds and routine.

Often – while creeping down Oxford Street on a Saturday or queuing up for an easyJet flight to Las Palmas or, perhaps, when stumbling upon a ‘reality’ show on TV – I am reminded of Jean-Paul Sartre’s wily assertion that ‘hell is other people’. Well, it’s a bit late now, but perhaps Monsieur de Beauvoir should have considered extending his existence beyond the absurdist realms of his Rive Gauche coterie and taken in the glorious isolation of the phenomenal Drôme Provençale and Vaucluse regions of France, where sweet-smelling lavender fields stretch out to bring a linear purple hue to lush valleys between mountain ridges and rolling hills.

In Sartre’s eyes, the Gorges de la Nesque that Monday would have been rather heavenly – not simply because of a grandiosity that bordered on the biblical, but for the presence of just one other soul: a smiling old man with silver hair out on his daily morning spin. That he had silver hair was of no doubt for he was not wearing a helmet, these being quiet roads devoid of traffic. The only vehicle we passed along the whole of the gorge belonged to a gardener, who we later saw meticulously trimming a hedge with Lynchian verve next to a small honey farm, the only building on the entire 18-kilometre stretch of road.

Through his bushy moustache, the old boy bade me ‘Bonjour’ before effortlessly peeling away on the gradual gradient on a vintage Merckx single-speed. Despite the crisp morning, he wore nothing but a plain regular kit – unlike Terry, who by now took to the start each morning in skiing gloves and jacket; or Bob, whose pasty old mountaineer’s legs, criss-crossed at the knees in ‘magic tape’, remained perpetually under wraps, despite his bold assertions of being ‘climate neutral’. Like most keen cyclists of his age from the countries we visited, the old Frenchman had a pair of tanned, sturdy legs long versed in transporting a tummy that betrayed a soft-spot for his wife’s excellent cooking. Later on, before the first of a series of four stone tunnels cut through the overhanging cliff, I passed him on his way back; he had presumably ridden to the end of the gorge and was now freewheeling home to coffee and croissants.

Part of me felt a little embarrassed to be overtaken by a moustachioed grandpa with a one-gear bike not overly dissimilar to those used by the early trailblazers of the Tour at the turn of the twentieth century. But this was effectively his garden path and I was taking it all in, stopping occasionally in failed attempts to capture the canyon’s muted splendour with the pixel paucity of my phone camera. Weary from my Ventoux escapade the day before, I still found the mornings cruel on my knees and so habitually rode off the back until I had warmed up and the painkillers had kicked in. Besides, I was trying to think of a joke I could tell the others at the coffee stop in Sault that didn’t involve a punchline including the words ‘pepper’ or ‘vinegar’, worried that even I might not be able to conjure up a credible ruse featuring a donkey attack (or ‘ass-sault’).

One day later, as we rode up yet another empty gorge at the foot of our morning ascent of the Col de Prémol, I traded places on numerous occasions with a local rider decked out fully in the old white kit of the Française des Jeux team – the second time after I had slowed to chat to Bob about his two sons back in the States. The climb was getting steeper and a light headwind had now become pretty blustery.

‘Do you reckon I can catch him again?’ I asked Bob, gesturing towards the man, who was now about 100 metres out ahead.

‘I know you can,’ he replied.

How could I refuse to take up the gauntlet now? So I dug deep and duly swept past the lone escapee for the third time in less than half an hour. We uttered a few awkward pleasantries that soon, at the summit, would be repeated for a fourth time after I had stopped to await my prize from Bob (I had run out of ibuprofen and so Bob – a veritable mobile pharmacy – assumed the mantle of makeshift soigneur until I replenished my stocks).

Since leaving Mazan and the nursery slopes of Mont Ventoux, the Giant of Provence had still cast a shadow on our pedal strokes – just as she had done on the approach to Avignon days earlier. From the top of the Gorges de la Nesque, the white dome of the summit loomed on the horizon – and it returned to our gaze as we edged out of Sault and on numerous other occasions as we rode over successive peaks of the low Alpine foothills. Looking south from the summit of the main climb of the day, the blissfully secluded Col du Soubeyrand (994 metres at 7 per cent), our eyes were naturally drawn to the geological wonder of the Rocher de l’Aiguier, a giant set of parallel rock fins some 90 metres tall and several hundred metres long that rise above the hamlet of Bellecombe-Tarendol like some kind of earthly UFO. But gazing beyond the lavender fields and over the black volcanic formations that characterize the first of many horizons, we saw the tiny upside-down syringe jutting up from what appears to be a snow-clad summit.

Before turning my back on Mont Ventoux for the final time, it struck me that Alan and his friends from the Sydney bike club Velosophy, who were being led by Dylan in their corresponding tour, were probably up there at the very same moment, basking in sunshine and taking in the Provençal panorama a day after the vista no-show that capped my own ascent. With Dylan and Sam separated into two different groups, extra guides with expert local knowledge had been drafted in. James, who came with us, and Mark, who became Dylan’s deputy in the second Alpine group, were seasoned resort workers from Morzine, where they skied in the winter and rode bikes in the summer. Given that some of the Antipodean members of our group had no first-hand experience of the Alps, it was a bonus to have someone like James who could regale them with stories from his five years living at altitude.

Hannibal, too, used a similar tactic when entering the Alpine foothills, enrolling a chap called Magilus to act as a guide and ambassador. Magilus was chief of the Boii, a Gallic tribe from northern Italy distinguished by their drunkenness, who boosted Carthaginian morale no end by boasting of the fertile delights of the Po valley and promising Hannibal support from the disgruntled Padane Gauls, who were already rebelling – to devastating effect – against Roman attempts to subdue their region. Hannibal had originally enlisted Magilus’s help by sending on envoys to shore up alliances beyond the mountains – in the same way that a team leader in cycling might order his domestiques up the road in a break to pave the way for his own decisive attack. The Boii and their allies the Insubres were renowned for their savage appearance, blood-curdling war cries, and general ferocity – enhanced by their perpetual insobriety. In short: the last thing an invading army would want to have to face after crossing Europe’s most formidable natural barrier.

Knowing that the tribes were both accommodating and universally in favour of an uprising against Rome came as a massive bonus for Carthage. Indeed, one of the reasons Publius Cornelius Scipio was so slow to send his army to face Hannibal in Spain in the first place was that he had been caught up trying to put down a rebellion of these very same tribes. And now, having chanced upon Hannibal’s army when popping into Marseille to refuel on pastis en route to Empúries, Scipio had decided that his best bet was to return to Italy to defend the Po valley.

Keen to keep ahead of the enemy, Hannibal and his men marched quickly through the Alpine foothills – although it took his army, which stretched out for 20-odd miles, six days to cover the kind of distance we were covering on bikes in just one. At first, things went well, with Hannibal’s army managing to reach the foot of the Alps without opposition. One canny piece of diplomacy saw our hero successfully adjudicate a kingship dispute between two warring brothers (think Andy and Frank Schleck coming to blows over who should lead their Trek team). Hannibal took the side of Brancus, the older brother, and helped reinstate him to the throne – a move which garnered him support in both supplies and protection.

But things didn’t entirely go the way of the Carthaginians. Shortly after Magilus had returned home to see his Boiis, Hannibal found his army under attack in a region ruled by the fierce Allobroges tribe. It is thought that the ambush happened in what is today known as the Gorges des Gats, which we rode through on stage 11 of our journey, the day after leaving Mazan. It’s an obvious place for an ambush: the road (which was probably a mere track back then) hugs the side of the twisting Bez river and is flanked on both sides by increasingly high cliffs. Even at midday, when we rode through, sunlight fights to reach the bottom of the gorge owing to overhanging rocks and numerous narrow tunnels. As you can imagine, it’s the kind of road that greets drivers with a series of those red triangular signs depicting rocks of various sizes tumbling down cliffs. It’s a shame they didn’t have any of these warnings in 218 BC when the Allobroges rolled rubble from above and squashed all manner of living Carthaginian creatures – from unfortunate soldiers to baggage animals and livestock.

Hannibal, however, was playing double bluff. He had suspected an attack was coming and so led some of his best troops out of the gorge and above the enemy’s position on a higher pass. From here he positioned his best archers on the overhang. With their backs to the cliff, the barbarians had nowhere to run and were picked off by arrows and stones, falling to their deaths and contributing to the general chasm of doom below. God knows what the neutral tribespeople further downstream thought when their drinking water turned red for a day.

Instead of having to sustain ourselves on an impromptu stew using fresh meat scraped off the rocks, once we emerged from the gorge we had the luxury of a delicious picnic lunch and took up position on a grassy verge overlooking the small hamlet of Glandage, at the foot of the Col de Grimone. The feeding of around 30,000 men was a huge undertaking for Hannibal, whose army relied on the fertility of the land and the goodwill of local tribes to keep the Alpine wolf from the collective Carthaginian door. We, on the other hand, simply relied on our guides to ensure a daily picnic hamper in sync with the lofty standards to which we had become accustomed, helping us to pedal on until our next gluttonous evening bonanza.

So when James – at the eleventh hour and on his first day behind the wheel – was forced to put on a hasty spread when our restaurant plans fell through on stage 10, he was always going to be up against it. Little did he know that over the course of the previous nine days, Dylan and Sam had been consistently raising the bar, adding another goat’s cheese here, an apple tart there, perhaps a fourth variety of charcuterie or some fresh strawberries. The standard had already reached quite epic proportions when James – preoccupied with trying to locate Roddy, who was feeling under the weather and needed to hop in the van – was summoned to pick up lunch for the entire group. Cue what became . . . the First Picnic War.

Of course, it didn’t help that it was already well past 1 p.m. and we were in a sleepy valley in the Drôme where every town seemed to be shut for the off-season. Nor did it help that James wasn’t au fait with our fussy eating habits. When sustenance did arrive, you could almost see Bernadette’s nose crinkle up in displeasure at having to even contemplate a ready-made sandwich accompanied by a packet of Bolognese-flavoured crisps. It was clear that there was disgruntlement in the ranks. Had Bernadette been part of Hannibal’s army, desertion could well have been on the cards.

Luckily for James (and us), that evening’s meal more than made up for any supposed calorie deficit. Our first two nights on the apron of the Alps were spent in La Motte Chalancon and Mens – two small rural towns largely in the middle of nowhere. After a stream of plush accommodation, our beds for both nights were in two simple auberges without restaurants, forcing us, like Hannibal, to seek help from the locals for our evening sustenance. In what was a welcome shake-up from our usual lavish dinners out, we had successive nights eating as guests in people’s homes – the first in a rustic farmhouse with a local farmer and his wife, and the second in a wonderfully renovated seventeenth-century manor house owned by a former world record speed skier.

‘Just wait until you try the boar stew from the farm we’re going to tonight,’ Terry told us as we tried to hold down those Bolognese crisps ahead of the Col du Soubeyrand.

‘How do you know we’ll be having boar stew?’ I asked.

‘Well, it’s what we had last year,’ Terry replied, as if logic dictated an omnipresence of boar bourguignon.

‘I spoke to the owner,’ said Sam. ‘It’s not boar stew this year, I’m afraid.’

‘Oh, no. That’s the only reason I came back,’ said Terry, gloomily.

‘But don’t worry, Terry. I mentioned the stew and they may do it as a side dish.’

‘Ah, Sam. You made my day.’

Dining at the peasant’s table – and a foreigner’s one at that – may sound like Nigel Farage’s worst nightmare but the expression table paysanne doesn’t hold the derogatory undertones of its literal English translation. This is how the French describe the arrangement whereby outsiders can enjoy a home-cooked meal in a traditional setting alongside their hosts. In many ways, Benjamin and Angelina Mroz were very much modern-day peasants in that their livelihood largely depended on the land they cultivated and the livestock they raised. If Angèle’s cooking was the star of the show then Ben’s input cannot have been underestimated. The large wooden conservatory in which we dined that night had been built by Ben last winter while his wife was supplementing their income with a season-long job at a nearby ski resort.

Ben’s biggest duty on the farm was to tend to his thirty Limousines cows – although he was probably down to twenty-nine and a half after our carnivorous showing. A warm beef terrine accompanied by a zingy courgette flan and a liberally dressed green salad got things off to a promising start. This was followed by grilled strips of beef (à gogo – all you can eat) with some rustic roast potatoes and a hearty ratatouille – not to forget Terry’s side of wild boar stew, which certainly lived up to the billing (although predictably debased the air quality of our room later that evening). A local cheeseboard fired further jabs at our almost sated appetite before a prune compote and chocolate brownie delivered the knock-out blow.

Make no mistake – this wasn’t haute cuisine. It was good, honest, no-frills food – à la bonne franquette, as the French would say – and just what was called for after another hard day in the saddle. Everything we ate at the Table Angèle – besides the local cheeses – was faîtes à la maison: either raised by Ben at the Ferme Mroz or grown in his wife’s vegetable garden. Glorious in its simplicity, the meal was also superb value for money at just €20 a head. The interaction with local people also broke up the routine of formal hotel and restaurant dining, giving at least James and me – the only French speakers – a different perspective on the region we were riding through. The Mrozes were a lovely, hardworking couple with strong country accents and a staunchly parochial mindset. Seeing that they had not even heard of Mens, our destination for the next day, it would have been no surprise had they admitted never to have set foot in Paris.

Yves and Nanine, on the other hand, were certainly privy to the high society of the capital. In fact, the whole set-up at La Maison de Bonthoux the next evening couldn’t have been more different. On entering the well-kept garden of the refurbished four-hundred-year-old manor, a smell of melted cheese waylaid my progression into the main room, where the rest of our group was enjoying an aperitif. Inside a small outbuilding a white-haired man in an apron, blue shirt and chinos was standing over a stone oven where a potato gratin bubbled away alongside a roasting leg of lamb. The aroma was as ambrosial as the sky on the horizon was red. This was Yves, our host for the night, and about as peasantly as Hugh Bonneville.

While watching the sun set over the mountains, we talked about the time he spent in England as a student in his early twenties (‘Ah, those were the days – the local women were so charmantes’). For six, clearly memorable, months in the Swinging Sixties, Yves lived in Dorking and said he remembered rambling on Box Hill, the slight mound that featured heavily in the London 2012 Olympic road race route (and which since has become a cycling rite of passage for hobby riders in the area). Yves was no stranger to the Olympics: once the world record holder in speed skiing, he played a starring role in the opening ceremony of the 1968 Winter Games in Grenoble, and counts among his good friends the skiing legend Jean-Claude Killy. When I introduced myself properly to Yves he laughed and beckoned me round to the back garden where a large vintage red tractor had pride of place.

Pointing towards two donkeys grazing in the field yonder, he said: ‘That’s our Félix, over there, with Margot.’ It was the first time I’d met another ass called Felix.

We joined the others for a glass of white wine and a nibble of some of Nanine’s home-made pissaladière, which, while sounding about as appetizing as a pair of my bib shorts, is actually an exquisite Provençal pizza-style focaccia topped with onions, olives and anchovies. Nanine further spoiled us with an innovative cold soup of cucumber, courgette and guacamole, which was so tasty I had a second helping. We then transferred to the table for Yves’s pièce de résistance: the succulent lamb and sizzling gratin, which was cheesy enough to warrant a second and third portion.

Following a call of nature, James remarked that there were lots of old photos of propeller planes up on the walls of the loo. ‘Ah yes, it’s because I am a qualified pilot. It’s just a little hobby,’ said Yves, whose other hobbies no doubt included snowshoe biathlon, hot-air ballooning and Arctic polo. That Yves could handle a joy stick was no surprise. Merely talking to the man was enough to ascertain that he was clearly a bit of a bon viveur who had probably enjoyed all the trimmings that came with being relatively famous and at the top of his game in an extreme sport which was all about speed and taking risks. Nanine must surely have been the last in a very long line of female admirers. There must have been a time when Yves had to put his speed skiing into practice simply to evade the ladies queuing up round the block. Even now, in his seventh decade, he clearly still had it.

Dessert – a creamy pear flan and some chocolate cake – was followed by a cheeseboard boasting three goat offerings and a zesty Bleu du Vercors. No donkey cheese from Margot, though, which was unfortunate as apparently, preposterous though it may sound, donkey cheese from a particular farm in Serbia is actually the most expensive cheese on the planet: the white, crumbly, Manchego-style ‘pule’ costs £1,000 per kilo and all known supplies of it belong to tennis ace Novak Djokovic, an unlikely cheese-hoarder if ever there was one.

Serbia is also responsible for a donkey-milk liqueur described by one food critic as blending ‘Italian Limoncello with a slice of Roquefort’. In the absence of such a frightful fusion, we settled for a ferociously strong prune liqueur, which burned the back of our throats as Yves and Nanine talked about their three sons. The oldest was a restaurateur, the youngest a ski instructor, and the middle son none other than David Vincent, a former world champion snowboarder, who now, aged 42, lives a quiet life with his family as a beekeeper.

As we said our goodbyes following the meal, we were given a pot of David’s honey. It made an excellent accompaniment to the innumerable varieties of goat’s cheese that we sampled on subsequent picnics during the high Alps. A sweet touch to the, ahem, fromarginal gains that were the cornerstone of Team Hannibal’s pie-in-the-sky approach to cycling.

Talking of picnics, our second-day lunch in Glandage – procured by Sam, whereby avoiding a Second Picnic War – served the dual purpose of showing James just how we rolled while compensating for his previous failure to couper la moutarde: a tomato and avocado salad, as well as fresh peaches and olives, complemented the usual array of hams, cheeses, salamis and baguettes (doughy in the middle and crispy on the outside).

‘OK, now I see why you guys weren’t so excited about my lunch yesterday,’ he duly noted. More than suitably replenished, we made our way on to the Col de Grimone – at 1,318 metres, the highest climb of the trip so far for those unindustrious souls who had opted out of Mont Ventoux. (Incidentally, it was also some 400 metres less lofty than the Turó de l’Home climb I had tackled in harebrained isolation on our opening day warm-up back in Spain.) It’s a truly scenic climb with a testing maximum gradient of around 9 per cent. I started well back but timed my surge to perfection, reeling in the early pace-setters Bob, Bernadette and Melbourne John with ample time to stop, take some photos, and cross the summit in an invisible polka-dot jersey.

The Col de Grimone has been used just twice in Tour history, most recently in 2002 when Belgium’s Axel Merckx, son of the great five-time winner Eddy, crossed the summit in pole position. That day, Merckx crested four out of five summits in the lead but faded on the final rise to Les Deux Alpes, finishing third behind Santiago Botero and Mario Aerts. (Botero’s excessive testosterone level was once found to be almost five times the maximum level for normal people, but he was cleared by his national Colombian cycling federation after his doctor, a certain Eufemiano Fuentes, demonstrated Botero’s natural aberrancy. As for Aerts, the Belgian was one of fifty-odd riders caught up – but never charged – in the infamous police raids on team hotels during the Giro one year earlier.) Merckx clearly had a soft spot for the Grimone, for he also crossed its summit with a lead of over a minute midway through a 219-kilometre stage in the 2005 Dauphiné before winning solo in Grenoble – his last major scalp before retiring.

While it must have opened many a bike-shaped door, trying to forge a riding career in the shadow of his legendary father must have been as hard as it was for Yves’s sons to replicate their father’s panache with the ladies. Merckx Junior was no wallflower – during a 14-year career he finished tenth in his debut Tour in 1998, became Belgian national champion and a Giro stage winner in 2000, and took bronze in the Athens Olympics of 2004 – but he was still somewhat eclipsed by a five-time Tour and Giro-winning father widely regarded as the most accomplished all-round cyclist to have graced the planet.

If Eddy was ‘The Cannibal’ then son Axel was at best a vegetarian who enjoyed the odd ham sandwich. (Those who wish to take into account his links with an infamous pharmacy in Bologna and his subsequent ‘suspicious’ blood test from the 1998 Tour can probably downgrade his status to vegan; either way, it wasn’t as if Axel was anorexic.) Instead of trying to rival his father’s exploits, Merckx Junior cannily vowed to make his own mark by achieving things his father never did – such as win the Paris–Tours classic or a stage atop Alpe d’Huez.

He failed miserably on both accounts – his highest finish in the final classic of the season being fortieth in 1996 and his best effort on the Alpe seeing him trickle home almost three minutes in arrears in 2006. But that Olympic medal was a feat that eluded his illustrious father, while Axel did become the first Merckx to take second place in a Tour stage finishing in the cartoon capital of Angoulême (a victory of sorts).

Both father and son were – still are – very close to Lance Armstrong. Axel’s career started in the same Motorola team as the Texan, and from 1992 to 1996, Eddy, who opened a bike factory in Italy after retiring, supplied equipment to the American team. Indeed, both Axel and Lance shared the same private trainer in the form of a certain Michele Ferrari, the controversial doctor who claimed he was personally introduced to Armstrong by Merckx Senior.

When Armstrong was diagnosed with testicular cancer, Papa Merckx was extremely supportive: not only was he by Armstrong’s side when the Texan went for his first ride after leaving hospital, it was Merckx who convinced his friend that he had what it took to become a Tour winner once he was in remission. And when, in August 2012, Armstrong announced that he would not contest the United States Anti-Doping Agency ruling that he had presided over ‘the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that sport has ever seen’, Merckx swam against the current to offer his support, claiming the whole case was ‘deeply unjust’.

‘Lance has been very correct all through his career. What more can he do? All the doping controls that he has done have come back negative,’ Merckx told the Belgian press. He would have been ‘crazy’ to have done ‘something so silly’ during his career. For his part, Axel denied that Armstrong’s refusal to contest the charges was an admission of guilt. His buddy was merely worn down by the constant allegations, he said. ‘He’s giving up because enough is enough. It’s damaging his image, it’s damaging his foundation, and I can see where he’s coming from.’

Indeed he could, for Merckx Junior was the director of the Bontrager-Livestrong development team that was founded in 2009 thanks, in part, to Armstrong’s long-standing ties with bike manufacturer Trek (Merckx still is director of the U23 squad although Livestrong has since been dropped as co-sponsor). Axel claimed he was speaking ‘in the name of my family’ when he reiterated his ‘respect’ for Armstrong. ‘He’s a friend and he remains my friend, and he’s always going to be my friend. I’ll stand by him when he’s being bashed about.’

But it didn’t take long for Merckx père to swim with the tide. Just one month later he had become both ‘amazed’ and ‘sick’ at the revelations surrounding Armstrong. ‘I met Lance many times,’ he said. ‘He never spoke to me about doping, doctors or other things.’ Peculiar, given their shared contact with Ferrari. When Armstrong finally went on the record and admitted doping his way to seven Tour victories to Oprah Winfrey in an exasperating TV interview in January 2013, an ‘extremely disappointed’ Merckx was in full digging mode – either that, or he was getting a little befuddled in his old age.

‘I didn’t see it coming,’ he said. ‘I don’t see how he could get to that stage, to lie to everyone and all the time.’ Despite his previous assertion that they never brought the issue up in conversation, he said that Armstrong ‘often looked me right in the eyes when we discussed doping and obviously he said “no” ’. Not mincing his words, the Cannibal claimed he, like so many others, had ‘fallen into the trap’ of taking Armstrong’s word about his training methods. And yet, regarding the doping allegations that surrounded his own career, Merckx went down a familiar road, saying: ‘I was clean, I know that. Every day there were controls at races.’ Indeed there were – and Merckx tested positive for banned substances on three occasions, the first time resulting in his expulsion from the 1969 Giro (despite his claim that he’d been framed).

I remember bumping into Eddy in Adelaide in 2012 during the Tour Down Under. While fellow five-time Tour winner Bernard Hinault is an ever-present fixture on the podium at the more mainstream races such as the Tour and Paris–Nice, Merckx gamely puts in appearances in far-flung places like Qatar and Australia. Given his track record of being the Pelé of cycling when it comes to bungling a quote, perhaps the downgrading of the Cannibal to the poor-man’s Badger for the twenty-first century is understandable. I made this observation in a blog entitled ‘Nice guy Eddy’ and incurred the wrath of one reader, who likened me to a ‘hooligan who pisses on a memorial to a war they were never part of’, which I thought was a bit extreme.

While awaiting the start of the evening criterium-style race through the streets of Adelaide that preceded the Tour Down Under proper, I asked Merckx who was his tip to win the season’s week-long curtain raiser. His answer was Stuart O’Grady, who was turning out for the newly founded Australian GreenEdge team that was making its debut appearance in the pro peloton on home soil. When pressed on why he felt a veteran rider whose last victory came some four years previously could win this time, Merckx said: ‘Because it would make a good story.’ Unsurprisingly, O’Grady didn’t win – but his team-mate and fellow Australian, Simon Gerrans, did.

What did make a good story, however, was the sudden retirement of O’Grady in 2013 following the completion of his record-equalling seventeenth Tour de France. While hardly a surprise (O’Grady was a fortnight away from turning 40), the Australian’s decision was rather controversial for it came on the eve of the publication of a French Senate report detailing EPO use in the 1998 Tour. In the report, O’Grady was named alongside a cluster of riders – including Axel Merckx, incidentally – whose re-tested blood samples were deemed highly suspicious for EPO use. The same day, O’Grady confirmed that he had taken the blood booster prior to the ’98 Tour – in which he won a stage and wore the yellow jersey for three days – but had been sufficiently scared by the fallout of the Festina scandal to press the eject button.

In short, O’Grady went down the Bill Clinton route of admitting to smoking just the once, but not liking the flavour, coughing when inhaling, and never trying it again. That’s to say, he remained a nonsmoker during his time at a Cofidis team fraught with doping innuendo in 2004; there was categorically no puffing on Bjarne Riis’s pipe at Team CSC when he was transformed from a sprinter to a super-domestique often seen on the front of the peloton setting a savage pace up fierce climbs for his team leaders; no cigars, even, when O’Grady became the first Australian to win a major classic with a ballsy solo victory in the 2007 Paris–Roubaix. Essentially: giving the performance enhancers the cold shoulder actually enhanced his performance.

O’Grady’s carefully measured confession days after Chris Froome’s Tour win set the tone for other similar disclosures, most notably from Canada’s Ryder Hesjedal, whose unexpected overall victory in the 2012 Giro was feted as a sign of a cleaner era for cycling. That narrative was somewhat skewered when Michael Rasmussen released his book and claimed that he had taught Hesjedal how to inject EPO back in his days as a mountain biker. Although Hesjedal did not confess until the publication of the book the following October, he had been aware that his case was being investigated since the turn of the year – which may explain his rather lacklustre results since being under the spotlight (illness and poor form forced him to withdraw one week into the defence of his Giro crown, while his seventieth place in the Tour was his lowest ever finish on a Grand Tour).

When Hesjedal did eventually confess he claimed he gave up doping after a solitary toke of the metaphorical cigarette. In the past decade – which had seen the Canadian ride at US Postal during the Armstrong era and Phonak during Floyd Landis’s stewardship before joining the stringently anti-doping set-up at Garmin – Hesjedal had not used EPO. In winning the Giro nine years after putting his ‘mistakes’ behind him, Hesjedal was asking the cycling community to believe that he had joined the exclusive club of riders who quit doping in order to win a Grand Tour clean.

To paraphrase Eddy Merckx – all these things do indeed make good stories.

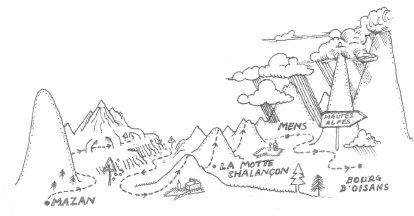

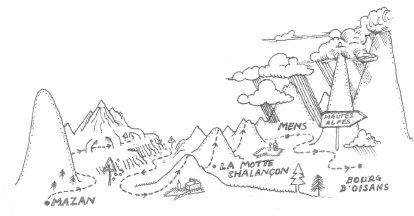

Crossing the Col de Grimone inspired a mixture of excitement and trepidation. The view from the top is nothing short of spectacular, with a lush valley rolling towards a row of pointy, pine-covered peaks. But it’s what lies behind these comparatively small triangular-shaped hills, rising up and disappearing into the clouds, that really took our breath away. And if the sight of the Hautes Alpes looming on the horizon gave us the jitters, then it must have roused a rattling din as the collective knees of the Carthaginian soldiers knocked together in panic.

Livy summed up the awe and apprehension of Hannibal’s men as they approached the high Alps with this colourful passage: ‘The awful vision was now before their eyes – the towering peaks, the snow-clad pinnacles soaring to the sky; beasts and cattle shrivelled and parched with cold; the locals with their wild and ragged hair; everything stiff with frost. All these horrifying sights gave a new edge to their fear.’ While we didn’t come across too many crazed locals, it was easy to put yourself in the shaking sandals of the invading army.

To enhance my feelings of escapism, I had earlier done something that I rarely do while cycling, and plugged into my iPod as we negotiated the isolated roads of the Drôme valley. But even without the Kenny G sax solo that accompanied my descent of the Grimone I would not have been able to keep it together.

As the trees cleared and I was gifted my first glimpse of the verdant basin below, my first reaction was to laugh and then to hold back the tears. The vast tapestry of green that stretched across the convex lenses of my sunglasses was a staggering sight reminiscent of the kind of grand, nineteenth-century tableaux that you might see hanging in the Flemish Masters landscapes wing of the Louvre. In fact, the arched viaduct that traversed a small hollow below looked a darn sight more like the bridge in the Mona Lisa than the Baron de Synclair’s aqueduct at Ansignan . . .

Having done an Axel Merckx and crossed the summit in the lead, I was soon near the back of the field after rider upon rider passed me by as I was sucking in my surroundings. When Merckx led the Tour down this same road back in 2002, he rode on with his fellow escapees towards the Isère valley and Les Deux Alpes, passing through the rather sombre town of Mens, which was our destination for the night. We still had 30 kilometres to ride and a rather nasty sting in the tail: an unavoidable section on the main road that ran north towards Grenoble, ‘the capital of pettiness’ so loathed by Stendhal.

Adding fuel to the fire, this busy stretch of road, which rose steadily uphill on a perceptible gradient and seemingly interminable northern trajectory, was accompanied by a fierce headwind that made cycling about as enjoyable as multiple lashings with an electrified whip. Luckily, James had also slowed on the euphoric descent and so we could trade pulls on the front. For those ghastly few kilometres his vocabulary would have made an arm wrestle between Bradley Wiggins and Gordon Ramsay a kids’ picnic of pleasantries. But his heroic pulls were enough to expunge the lingering memory of those ghastly Bolognese crisps.

Once over the ridge, the ordeal disappeared. Free from sharing the road with massive lorries chugging uphill in third gear, I peaked just above 80 kmph on the sweeping downhill as yet another sumptuous valley – nestled between the lofty national parks of Vercors and Écrins – opened out ahead. We ditched the main road and joined a scenic lane towards Mens before I buggered off to do a little detour to ensure that my kilometre count once again hit three figures (having 24 hours earlier broken the 1,000-kilometre barrier since Barcelona).

When we did continue on the same road as Merckx the next morning it was underneath a dull canopy of cloud. So much for the old ‘red sky at night’ adage: I couldn’t speak for the shepherds, but there weren’t many delighted cyclists out there as we skulked up the sodden Col d’Ornon en route to Le Bourg d’Oisans, the gateway to the high mountains.

The Ornon is a drab climb at the best of times, a zigzagging affair on coarse tarmac in which each zig and zag (there are three apiece) lasts for the best part of 500 metres. Doing it in heavy rain was a fairly joyless experience which at least one of us (Roddy) avoided by clambering into the van. For those of us who had ambitions beyond an early finish at Bourg d’Oisans, there was an added sense of trepidation for this was the day that the mythical twenty-one hairpin bends of Alpe d’Huez were there for the taking – a prospect, in this rain, about as appealing as twenty-one punches to the gut after a bellyful of Djokovic donkey-milk liqueur.

The Tour had come this exact way for stage 18 two months earlier, the riders heading up from Gap and going through dreary Valbonnais (where we took cover to have coffee, Mars bars and freshly picked strawberries in the only open cafe) before tackling the Ornon and descending down to Bourg. In a historic first for the race, the route then included back-to-back ascents of Alpe d’Huez, separated with an unprecedented climb and descent of the Col de Sarenne.

In a bid to recreate an authentic Tour experience, and show solidarity towards the exploits of my cycling heroes, I had promised myself, my family, my friends, and my fellow Hannibal riders that I would attempt to recreate the gruelling finale of the queen stage of the 2013 Tour. Again, in my current sorry state, this was less appealing than forty-two cracks to the ribs, separated at the midway point by a severe pummelling to the groin.

To make matters even more lamentable, the 10-kilometre descent from the Ornon was in the process of being resurfaced, leaving a fine coating of grit for us to contend with as well as puddles, potholes, fog and dank drizzle. Much later in this whole adventure, when the remnants of the Velosophy bike group joined forces with the Hannibal hardcore for four days in northern Italy, I was to hear stories of downhill bliss and 85 kmph speeds from the Australians shadowing our party. The meteorological lottery that saw their ascent of Mont Ventoux carried out under clement blue skies graced them through the Alpine foothills and on to Alpe d’Huez. This descent to Bourg d’Oisans was one of the highlights of their entire trip. For me, it was hell – and not in the Sartre way, for I did it in complete isolation. No cars were out on this deathtrap of a road; no cyclists were crazy enough to brave the elements for a spin on a day as grotty as this; and I had no idea whatsoever where the others were, having decided to put myself out of my misery as quickly as possibly by riding as fast as I could to the finish.

Shivering and soaked, I rolled into Bourg a near-hypothermic wreck, my extremities a haberdashery of pins and needles. I procured my hotel key, headed straight up to the room, turned the heating on full blast, stuffed my shoes with newspaper, peeled off my kit and wrung out the sweaty brownness into the sink while running a hot bath, in which I wallowed until the grimy water had slumped to a temperature lower than my morale.

It was shortly after 1 p.m. when I threw on some dry clothes, rolled up in a ball of anguish and nodded off, only to be woken minutes later by a medley of groans and other human sounds associated with hardship and vexation, as Terry squelched up the stairs.

There was no way I was going to even attempt one ascent – let alone two – of cycling’s most celebrated climb, sandwiched by a perilous up-and-over whose maiden inclusion in the Tour months earlier was described as ‘irresponsible’ by a three-time world champion. No, siree.