IT SEEMED THE most respectful thing to do. Crowds had gathered outside the church, blocking the path. A bell tolled a single repeated dong. The hearse was ready, its boot open and awaiting the coffin being carried down the stone stairs by six men behind a priest clasping a microphone.

I could have tried to weave my way between the mourners. But many were teary or had their heads bowed, and this was a steep, gritty and narrow road leading to the top of the medieval hillside town of Costigliole Saluzzo. Colliding with a mourner at the funeral of a grande formaggio would have been a one-way ticket to my own interment. For there was definitely some Sopranos action going on. Those burly men in black suits and shades, for instance: clearly packing heat. So I did the sensible thing and pulled into the side of the road beside a large wall. I resisted the temptation to photograph the scene. But I still stood out – the only lanky cyclist in multi-coloured garb not here to pay his respects to the dearly departed.

The coffin safely placed inside the hearse, the vehicle started to edge down the hill at a snail’s pace. The priest chanted into the microphone from the passenger seat while the family and friends of the deceased shuffled along behind. It was a painfully slow process, comical almost, given that my destination was a mere handful of tantalizing metres further up the incline. Made worse by the knowledge that the plush Castello Rosso hotel had a pool, and I hadn’t gone swimming since that impromptu dip in the Gard near Avignon.

At least I had had time to act. Anyone coming up the road now would meet the cortège head on and be forced to stop and turn just as the climb kicked up. I thought of Terry and Sharon, who I had passed not so long ago. Quite how they’d cope with such a chain of events was anyone’s guess. I had visions of Terry ploughing into the hearse and getting himself arrested. The carabinieri of Piedmont were bound to be less accommodating than the comely policewomen of the sleepy Pyrenean foothills. His views on truncheons could change irrevocably.

But it was Sharon who came off worst. She trudged into the castle’s leafy courtyard with her unbandaged knee covered in blood. They’d rounded the bend at the start of the climb just as the hearse appeared. Stopping suddenly, Sharon lost balance on the slope and was unable to click out of her pedals in time. A combination of grit and gravity did the damage; she now had a second gashed knee to even things out. The ghost of Michaela lived on. Miraculously, Terry didn’t come a cropper. With his momentum gone, he had to push his bike up the last section and past what he probably thought was a wedding.

‘Is there a bath?’ he asked optimistically. There was no bath. Yet the bathroom was a whopper – larger than some of the bedrooms we had shared. Double doors led out to a balcony, from which a stone staircase stretched up to a private terrace atop a tower. A week’s worth of festering kit washed in the basin with hotel shower gel, I adorned the balcony railing with these clean(er) garments dripping into the bushes below. Then off I went for that swim, picking up a couple of beers from the bar on the way back.

In matching white dressing gowns, Terry and I, like an old married couple, toasted our arrival in Italy as the sun went down, gazing over the fertile fruit plains of the Po valley from the scenic terrace of what was clearly the Castello Rosso’s honeymoon suite.

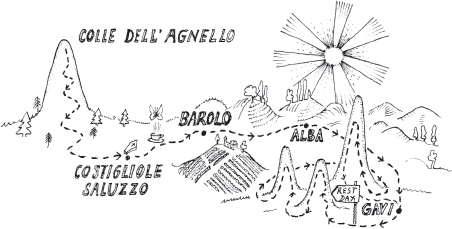

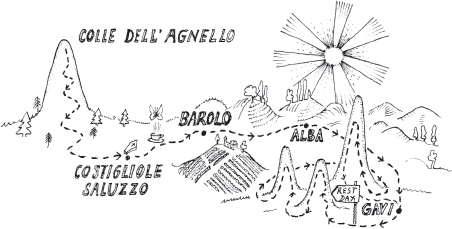

On the south, Italian side of the mountain, the angelic Agnel becomes the bleating Agnello, a sheepish downhill ride all the way for 60 kilometres, which we broke up with a late picnic lunch overlooking the Lago di Castello in sleepy Pontechianale, and a coffee stop in sweltering Sampeyre.

Noticing that the Colle dell’Agnello was perceptibly steeper than the Agnel, I was relieved not to be tackling this climb in reverse – as Andy Schleck did en route to his Galibier win. Unlike the French side, the slopes are peppered with pine trees giving the pass a less mystical but more dramatic feel. The task of negotiating numerous tight bends at a double-digit downward gradient was intensified by the presence of various animals to dodge. Packs of sheep ambled leisurely along the road. Marmots scampered from one side to the other, seemingly attracted by fast-spinning wheels. A large cow slouched on the grassy verge, its bulk encroaching on the side of the lane with the kind of bovine abandon you’d expect to see in India, not Italy.

The Agnello has been known to topple even the best. On the Tour’s first unscheduled visit in 2008, Spaniard Óscar Pereiro – the stand-in winner two years earlier following Floyd Landis’s testosterone-fuelled rise and fall – plunged off the side of the road approaching one of these very same switchbacks. Sliding on the wet asphalt, Pereiro went over the barrier, tumbled 5 metres down a rocky embankment and through a tree, and landed on the road below in agony, taking a branch with him. He has a tattoo of the date – 20 July, 2008 – directly above the 25cm-long scar where doctors operated on his broken arm, reminding him of how lucky he was to avoid a worse fate.

Having scaled the ‘Fence of Italy’, Hannibal’s army likewise suffered on the precipitous and slippery descent. Local barbarians weren’t the problem – according to Polybius, only ‘a few skulking marauders’ offered resistance; the big issue was heavy snowfall, rocky avalanches, icy slopes and the presence of a gigantic boulder which blocked the mule path. For four days, the Carthaginians were stuck while scouts searched for an alternative route. Huddled together, the elephants slept standing up, as desperate men – the Numidians in particular – took shelter underneath their vast bulk (about as sensible as grabbing forty winks on a railway line, I’d have thought). The feted Numidians may have been recognized as the best light cavalry in the ancient world, but their habit of riding in the nude with only a leopardskin sash over the shoulder wasn’t so effective in plummeting temperatures.

Eventually, Hannibal’s engineers came up with an ingenious solution. Livy writes of bundles of vinegar-soaked firewood being tied round the boulder which, once lit, caused the rock to crack, aiding its removal by pickaxes. This, too, was at a cost – for vinegar was the Pot Belge of the Carthaginian army, a mild pick-me-up and painkiller which helped keep morale slightly above zero (unlike the temperatures). Seeing their rations of sour wine spilled all over rocks would be the equivalent of a professional cyclist in the late 1990s having to flush his doping stash down the loo during one of the late-night police raids that were so de rigueur at the time. Personally, I think the soldiers should have put a positive spin on things: if your tipple of choice is both flammable and potent enough to crack rocks, it’s probably a good thing to keep it out of your stomach.

Emaciated, exhausted and looking every bit your average Tour rider, Hannibal’s soldiers and pack animals soon made it to the pasture line where they could refuel and gather strength. It had taken fifteen days to cross the Alps – one day more than it had taken us to ride all the way from Catalonia. Hannibal’s infantry had lost a third of its men during the crossing. Just 12,000 Africans and 8,000 Spaniards made it to the plains below. Six thousand cavalry survived the crossing, while none of Hannibal’s thirty-seven elephants perished.

Crossing the Alps had given Hannibal and his army the same aura of invincibility that, two millennia later, cycling fans, cancer survivors and fawning media outlets would give to Lance Armstrong and his US Postal team. One sports columnist, Bernie Lincicome, lambasted the rumours of foul play that soured Armstrong’s ‘astonishing achievement’ of winning the Tour in his return to the sport in 1999. ‘There is no point in paying any mind to the drug insinuations directed at the Tour de France winner when his story is far more inspiring than petty slander,’ he wrote in the Chicago Tribune. ‘I mean, a guy beats cancer and the Alps. Did they give Hannibal a drug test?’ Lincicome then suggested that Armstrong would even have won the race had he been forced to ‘ride down the Champs Élysées with a priest and a poodle on his handlebars’.

Bernie was not alone in kowtowing to the inspiring Texan. Wet behind the ears and unaware of the Irish journalist David Walsh’s brave attempts to expose the systematic doping behind Armstrong’s empire, I remember writing an article entitled ‘Lance’s Positive Lieutenants’ back in 2006 in which I lauded the ‘perfect track record’ of the ‘most heavily tested rider in the history of the sport’, concluding that it was the ‘brilliance’ of the seven-time Tour winner (and not something as nefarious as EPO) which was the ‘drug that ran through the veins of US Postal’. A few years later – as the US federal vultures gathered – PR guru Alastair Campbell, of all people, greeted his hero’s 2009 comeback with the assertion that ‘he is still adding to the legend’. Writing in The Times, Campbell reminded his readers of his favourite Armstrong quote: ‘Losing and dying – it’s the same thing’.

In Lance’s world ‘cheating and living’ clearly went hand in hand, too. His first Tour victory in 1999 was seen at the time as one of the sport’s greatest. While it would be followed by six more triumphs it also marked the start of a long struggle and countless battles that would ultimately result in the defeat and downfall of a man deemed untouchable. For Hannibal, crossing the Alps was also a mere stepping stone to bigger, more arduous challenges. It was one of the boldest military manoeuvres in history. But the war had only really just begun, and against an opposition capable of amassing three-quarters of a million troops against the invaders, the odds were almost as unfavourable as a contemporary Frenchman winning the Tour.

It felt as if someone had tried Hannibal’s old vinegar trick on the road down to Costigliole Saluzzo. Deep rivets and cracks broke up the atrocious surface, running along like uneven tramlines primed to catch a wheel and send riders headlong into the asphalt. A clean strip ran perilously close to the verge – otherwise the safest bet was to ride in the centre of the road and stay alert for traffic coming in both directions. The net result was that we hurtled towards the Po valley rather po-faced.

Roddy was proving quite an asset. His uphill ability may have been rather shoddy, but my Australian companion’s confidence rose now we were back on the zippy, flatter roads. On the gradual descent he picked a sensible line, only occasionally veering off dangerously into the path of oncoming traffic. When taking numerous pulls on the front, he was constantly alert and warning me of hazards on the road with slightly camp over-exaggerated gesticulations. There were times when he was so lively that he left me digging deep to fight back on.

The effort clearly got to him. Once alone (we had parted ways when I decided to nip off to a run-down town called Vernasca – primarily to clock the extra kilometre I needed to bag my daily hundred), Roddy pulled in for an ice cream at the first cafe he could find. That this was in an unsalutary place called Piasco – which smelled very much like it sounds – just a few kilometres from the final rise to the Castello Rosso, stressed the shift he had put in. Or perhaps merely underlined his astounding hunger for gelato.

Later that evening, Roddy and I spent much of the team’s al fresco aperitivo shooting the breeze about his custom-made Dario Pegoretti bike. Having clocked up numerous hours affixed to the roof of the van, the flash red-and-white steel bike had finally got a decent run-out on the ride into Italy. Looking every bit the North Shore Sydney-sider in a long-sleeved white polo shirt (collar up) tucked into some beige chinos and with a red jumper draped over his broad shoulders, Roddy proudly recounted Pegoretti’s impeccable CV as one of the great contemporary steel-frame builders.

‘I remember reading an article about Pegoretti in a magazine back in 2001 and it blew my socks off,’ he said. He ummed and ahhed about ordering a frame for years before taking a detour up to Pegoretti’s workshop in the Dolomites while in Tuscany for a wedding, visiting en route an old friend who was a school teach-ah in Veron-ah (Roddy’s honeyed Aussie tones could be a little harsh at times).

‘Once I met Dario in person, I just fell for it hook, line and sink-ah.’ In 2006 he was measured up in Sydney and then placed the order for a frame. He wanted a simple colour scheme (‘You are almost forced by practising law to become very conservative’) but Dario (an ‘artisan hippy’ who was ‘at the other end of the spectrum’) somehow convinced Roddy into opting for pearl white with a metallic fleck in the paint which, depending on the light, would emit a green or pink tinge. (I cannot emphasize enough how out of character this seemed.)

When Roddy’s bike arrived in Sydney in late 2007 – following a delay while Pegoretti recovered from lymphoma – he would take it out on regular early-morning rides in Centennial Park, where I myself had first grappled with a road bike (with those sock-stuffed Speedos for protection). Roddy and his friends took post-training coffees in a nearby delicatessen at 7 a.m. ‘The lady who owned the trattoria had some holy water from the Vatican and so we had a christening ceremony for the bike,’ he said, now in full flow.

I found Roddy a real character. Behind the shy and introverted interior, there was an erudite guy who was passionate about his hobbies and had a lot to say. It was a pity that the others seemed less impressed. I sensed that he had been unjustly shunned by the other Australians on the tenuous grounds that he was a bit of a smarty pants. He told me once how one of the ladies in the group was unnecessarily aggressive towards him on his first day. I told him not to worry – that he had not been the only one to receive such frosty treatment. But he was clearly upset about it. As we spoke now on the terrace, there was a perceptible divide: us at one end of the table, the others swarming around plates of canapés that were never offered in our direction. Of course, I could feasibly have misunderstood blinkered hunger for mild malevolence.

It didn’t help, though, that Roddy could easily be viewed as a cycling parvenu. When, for example, Bob turned up at breakfast wearing a La Vie Claire jersey, Roddy was quick to point out that it was not an original ‘because it’s clearly not the right shade of yellow for the Mondrian colour scheme’. This didn’t go down too well with the others, who used it as a stick to beat a man whose sermonizing about the sport – not to mention his gadgetry and impeccable riding attire – was out of kilter with his farcical tendency to crack as soon as the going got tough. A conflicting shade of yellow didn’t disguise the fact that Bob – twenty years Roddy’s senior – had yet to seek solace in the van.

But it wasn’t as clear-cut as that. As we tucked into our curious starter of baby squids stuffed with pistachios and spinach – clearly the result of a game of Ready, Steady, Cook in the kitchen – Roddy explained to me how he came late to cycling.

‘Sailing was my sport – it still is. I did it professionally before I became a lawyer and continue at a high level today. I took up cycling as a way of building up my leg muscles for sailing. Before long I became hooked.’ After a short-lived marriage broke down, Roddy moved to the Middle East in 2011 and his cycling duly suffered. He booked his place on our tour with a friend but found it hard to train in the desert, even when he shipped his Pegoretti out to Dubai. When his friend broke a leg in a skiing accident in Australia, Roddy was going to give up on the trip. But he came out despite illness and poor fitness to give it his best shot. ‘We may return next year and have another crack. I feel I haven’t really proved myself so far.’

After eating rich French food for the best part of two weeks, I was looking forward to some simple pasta dishes, but I’d have to wait a little longer. The curious squid-nut combo was followed by a thick, wholemeal tagliatelle with turbot, gurnard and prawns, which was rather stodgy and utterly tasteless. Oddly for seafood, the dish lacked salt. It also needed a kick and – Italians, forgive me – some Parmesan. While the other end of the table was being kept entertained by Richard and Simon’s increasingly well-oiled double act, Roddy and I resumed our conversation about his bike.

It wasn’t long before he had regrets about the wild paint scheme, pining for something more classic. But he was very particular – with his sights set on the vintage red and white of Eddy Merckx’s old Faema team from the late 1960s. Such a job could not be done in Sydney or bike-friendly Melbourne, apparently. Instead, he’d been recommended a specialist shop in California which, in turn, used a painter based out in the Rocky Mountains. So Roddy duly shipped his bike across the Pacific to San Francisco, where it went on to Colorado.

Was that not a tad excessive? ‘I was convinced they would do the best job so it was the right decision. But it was not without complication.’ Shortly after he shipped the frame, Roddy made the switch to Dubai. He asked the shop in California to send the end product to a friend of his in Rimini so that he could have a bike in Europe for training. But irregularities with the paperwork meant the frame was held up in customs. Roddy was forced to stump up two thousand euros to smooth things over.

‘How much did the frame cost in the first place?’

‘Frame and forks, four and a half thousand dollars. Add to that the groupset, wheels, seat and stem – plus shipping costs, the repaint job and the custom fee – and it’s more like ten thousand. But it’s worth it. I bought all Dario’s expertise and I think that’s cheap. Plus there’s a high degree of emotional attachment. It’s a one-off, hand-made for me. A lot of carbon frames are mass produced in Taiwan. I wouldn’t be seen dead on carbon fibre. I’m toying with getting a titanium frame as a back-up – not one of those gimmicky twisted ones that Sam has. But if I lost my current frame or it broke, I would definitely get a new steel Pegoretti.’

‘What about a wooden one?’ I asked provocatively, hoping Bob might hear. But he was too busy lapping up the raucous scenes as Richard and Simon cajoled a tipsy Terry into producing some classic material. He was currently explaining the bedrock of his happy marriage: ‘My wife was after a passport and I was after exotic sex. It worked for a while.’

‘This is just why I came back on the tour for a second year,’ Bob guffawed as the waiters arrived and, rather unexpectedly, started handing out cotton bibs covered in cartoon cows. By now we were all (except teetotaller Bob) sufficiently lubricated to play along with the bibs – even though no one else in the restaurant had been offered them.

Curiously, when our mains arrived they did not even warrant a bib. The tender slices of rare veal on a sizzling slab of slate with a bowl of diced potatoes were quite delicious, but there was no sign of an accompanying sauce to legitimize such protective measures.

Perhaps, we concluded, the bibs were part of a game the waiters played with foreigners – either to entertain or to humiliate. It was interesting watching how the various characters around the table dealt with the situation. Sober Bob, for instance, refused to even wear his, while Roddy took his off rather quickly, revealing once he did so a small red stain left on his polo shirt by the very dish – the saucy seafood pasta – for which an earlier bib might have been welcome.

Dessert came in the form of tiramisu – or what would soon be known as Terrymisu, in the light of my room-mate’s insatiable appetite for the sickly sweet, Marsala-infused Italian cake. Three of us still saw sense in sticking with the cow bibs. When Richard backed down, it was left to Melbourne John and me to have some kind of bib-off. Caving in under the pressure, John was out-bibbed by yours truly. But that wasn’t the end of it. If the restaurant was indeed playing a game with us, then I would rise to the occasion. The bib stayed on as we rose from the table, and as I walked through the restaurant, past the hotel lobby and up to my room. And seeing that no one asked for it back, I kept it as a nice souvenir.

The honeymoon suite didn’t get much action that night – although Terry ran the gamut of grunts and groans. Ear-plugged and content in the knowledge that an early Christmas present for my new nephew had been sourced, I dozed off trying to calculate the air miles of Roddy’s bespoke frame. Italy to Australia to California to Colorado to Italy to Dubai to France . . . by my reckoning that was over 50,000 kilometres.

And still Roddy had yet to ride it the whole way up a mountain. Next year, perhaps.

There are worse ways to spend a warm weekend than riding through the rolling hills of Piedmont and sampling its wares. While Piemonte – ‘the foot of the mountains’ – was the birthplace of modern unified Italy, you get the impression that the nation’s largest mainland region could cope just fine on its own, grazie mille.

Piedmont boasts the source of Italy’s greatest river, the Po, while its criss-crossing canals irrigate Europe’s most important rice fields and fruit farms. Unspoilt medieval hilltop villages – often crowned by castles or filigreed by fortifications – preside over rolling hills wearing the green corduroy of some of the world’s most prestigious vineyards, often surrounded by a hem of hazelnut trees. Italy’s most culinary progressive region is responsible for a ‘slow food’ movement that sets it apart from its more traditional neighbours, while its capital, Turin, is the centre of Italian industry, its roads abuzz with locally built Fiats and its offices humming with Olivetti computers.

Safe in the knowledge that their region is responsible for gastronomic delights on every point of the spectrum, the Piedmontese can dip breadsticks into Nutella (thanks to those hazelnuts), shave pungent white truffles on to their pasta and take their pick of local vermouths – making me, with my vintage Cinzano kit, something of a passing celebrity. Children are kept in check with Kinder Surprises, while should any ambassador host a reception, a precariously balanced tray of the region’s famous Ferrero Rocher chocolates can wow the guests – or perhaps they’d prefer a simple fruit salad of kiwis, apples and peaches grown on the plains? On weekends the people head into the mountains to ski, or go kayaking or trout fishing in the many rivers. And while taking a dip in the sea is not an option in the land-locked region, there’s always the splendid lakes of the north.

With the area so self-contained, it’s no surprise that tourism only plays a small fiddle in the ebb and flow of Piedmont’s orchestral life cycle. As the classy Cadogan Guide states, ‘If your Italy consists of Renaissance art, lemon groves and endless sunshine, you’d better do as Hannibal did and just pass right on through.’ Although it wasn’t plain sailing for our hero. Arriving with his army in a truly bedraggled state, Hannibal found his allies the Boii and Insubres as good as their word, which meant progression was quick. But another tribe, the Taurini, were not so accommodating. When they turned down Carthage’s offer of a formal alliance, Hannibal blew a gasket, ordering his troops to level the Taurini’s main settlement before executing all inhabitants. Nothing gains respect like a good bloodbath – especially when women and children are involved.

The locals were considerably more welcoming to our two-wheeled army and we had no need for such savage retribution. Our final stanza of the second leg of the tour was played out under hot autumnal sun, the early haze that gave a sheen to the flat plains or hugged the troughs of the emerald valleys replaced by a blue cloudless sky come midday. For the first time since setting off from Montseny two weeks previously, I put in back-to-back days without leg warmers, giving my pasty pins a chance to regain the tan that cruelly eloped with a sheet of warm wax back in Barcelona.

I was still unsure how I felt about the abrupt waxing of my legs. One upshot was that bedtime stroking yielded a distant reminder of what it was like to have a girlfriend (since taking up cycling, funnily enough, those had been few and far between – a decline inversely proportional to my growing collection of skimpy outfits). But that smoothness now seemed a lifetime away. Nocturnal rummages around the bedsheets – a rare extravagance given the Terry-shaped elephant in the room – were greeted with a slightly stubbly response: a reminder of that moment, a few months into a new relationship, when your better half lets things slip a little.

After the punishing crossing of the Alps we had all let things slip. The pace was considerably slower as we took in our surroundings and dedicated the weekend to enjoying the finer things in life. Once we hit the lush Langhe hills – the primary residence of the fabled Nebbiolo grape – we became inescapably entwined with the region’s strong viticultural traditions. Forget that the hills of Piedmont would be much prettier with fewer vines; they clearly wouldn’t be as profitable or famous. Nor would our pit stops have been as much fun.

There’s such a wealth of grapes in the area that the locals even use grappa as a disinfectant (at least, that was the impression I got when visiting the bathroom at our Saturday lunch stop in Monforte). Outside, eating a banana in the town square, an old man with a walrus moustache took a break from his weekend bike ride, his generous paunch held in place by a natty GSP Ferrero kit (otherwise known as Team Nutella), hugely out of place alongside his impeccable BMC Pro Machine (worth almost as much as Roddy’s Pegoretti). The old boy had just seen me ride up the 30 per cent cobbled road to the historic crown of the town to blow away the cobwebs of lunch, and nodded in approval on my return. Like us, he was en route to Alba – where a warm and nutty ambrosial aroma pervades the streets as it wafts down from the Nutella factory just outside of town. After a brief ride together we parted ways, for just down the road we had a date in the cellars of Barolo’s Castello Falletti for a spot of wine tasting.

Wine is to Barolo what chocolate spread and white truffles are to Alba. Big, powerful and tannic, Barolo is known as ‘the king of wines’ and is one of Italy’s most esteemed dry, full-bodied reds. For a wine to get DOCG Barolo status it has to be grown from 100 per cent Nebbiolo grapes on south-facing vines within the eleven local municipalities. From sampling various vintages it is possible to detect the kind of soil the grapes have been cultivated in: sandy soil packing a fruitier bouquet than the more tannic offerings from clay. Slightly sozzled, we rode on, resisting the temptation to join a queue of Germans entering the nearby Corkscrew Museum on the Via Roma.

Richard and I burned off the alcohol with an undulating 35-kilometre extra loop taking in some of the punchy climbs that featured in stage 13 of the Giro earlier in the year. Manx sprinter Mark Cavendish managed to keep in touch over the highest point at Tre Cuni and took the win in nearby Cherasco – exactly a year after plundering the corresponding stage of the 2012 race just down the road in Cervere. With Richard’s noble bulk contained by his ubiquitous Lampre jersey and my lanky self stretched out in the perma-slick colours of Cinzano, we were, if not in shape and stature, at least the sartorial envy of the locals.

The real Team Cinzano was a little-known Italian professional cycling outfit during the 1970s and early 1980s, made famous by their cameo appearance in the classic 1979 Oscar-winning coming-of-age story Breaking Away. Much to the delight of the film’s lead character, Dave, a gifted young cyclist from rural Indiana besotted with all things Italian, Team Cinzano come to town to take part in a series of amateur races. Irked by the presence of Dave effortlessly latching onto their train and prattling on in their native Italian, the Cinzano boys resort to underhand tactics, eventually sending their unsuspecting tormentor flying into a ditch by thrusting a pump in his spokes. In what would prove an uncannily prophetic commentary on the state of cycling in the years to come, Dave, crumpled in a heap, concludes that everyone cheats – most notably the very people he worships.

I drew a line at jamming my pump into Richard’s lightweight Canyon wheels, although, after the thorough workout he gave me on one particularly fast and sweeping descent, I was tempted to employ another shady Team Cinzano tactic on the subsequent vine-lined climb and use my companion to slingshot myself forward with a good old ‘Belgian Push’. But there was no need: the savage gradient and laws of gravity resulted in me riding clear to toast another minor uphill triumph.

If Barolo is the red king then the exceptional Gavi di Gavi is the region’s classy white queen. Delicate and dry, it’s a wine made from the exclusive Cortese grape and produced only by a handful of wineries, including our home for the second rest day, the Villa Sparina in Monterotondo, where a celebratory dinner would include a quite outstanding risotto made with Gavi di Gavi and a tangy soft-ripened robiola cheese. The smell was enough to make you go giddy, while the taste – salty, rich and strong – evoked many a happy moment in the company of other creamy curds. That was not all: the tender chunks of beef that followed had been braised in Gavi wine for a precise 21 hours before gracing our plates. I would have waited double the time for such a giving dish.

Exquisite wine was not the only luxury that our Alpine crossing had momentarily called time upon; a proper coffee had become a distant memory stretching way back to those early days in Spain. Now in Italy, coffee stops became something of a bonanza – the country’s gloriously bitter one-euro macchiatos going down like Bradley Wiggins on a wet descent. You could go anywhere and get an injection of caffeine of such performance-enhancing zeal that you’d be hard pressed getting it past Team Sky’s zero-tolerance charter. Proof of this came when Sam led us to an unprepossessing cafe in a petrol station forecourt on the outskirts of the glum industrial town of Morozzo. It was great that he was breaking up our schlep across a flat and slightly drab agricultural plain – but did he have to take things this far?

And yet the coffee was unexpectedly fantastic. What’s more, the ludicrous arrival of a dozen English-speaking cyclists of a predominantly mature age was a startling boon for the two busty waitresses used to spending their mornings being ogled by fat truckers. Not that there was an absence of ogling. Terry was not so quietly having a seizure, the birthmark on the side of his face no longer visible behind his blushes.

‘I feel like I’ve died and gone to heaven,’ he said to no one in particular.

‘What’s that, Terry?’

‘I’m in love. Just look at her,’ he said, giddily gesturing towards the curvy blonde in faux alligator-skin leggings and a black top low enough to reveal a butterfly tattooed upon her right DD breast. ‘That girl over there is perfection.’

A second brew inevitably followed. ‘This coffee’s like Viagra. I haven’t felt like this in years.’

Floyd Landis’s record of thirteen consecutive cappuccinos in one sitting seemed very much under threat until Sam poured cold water on Terry’s caffeine binge. But on the way out I approached the girls and put in an unexpected extra order. In a fit of giggles, they agreed to my request.

‘Terry – get behind the bar. But take a tray to cover your privates. We’re taking a photo!’

He didn’t stop smiling all day.

Terry, it has to be said, was in his element now the mountains were behind us. In the continued absence of Dylan – still leading the corresponding group of Sydney club riders – his father had really come out of his shell. As our kilometre count rose so too did his alcohol consumption. No meal was complete until the retired dentist had gone off on a rant about toothpaste (‘They never needed it in the old days’), the perceived merits of water births (‘What do the experts know? Can they actually remember being born?’) and, most frequently, his continued – and clearly exaggerated – subjugation at the hands of his tiny, yet clearly quite fiery, Mauritian wife (‘Will she ever stop nagging?’).

From their first night with us around the dinner table, Simon and Richard had seen how easy it was to coax a performance out of Terry. Here was a wind-up doll whose mechanism simply required ample lubrication and some gentle probing. And in Alba they put on the rubber gloves and got stuck in. But not before dropping the kind of bombshell worthy of a Christmas episode of EastEnders – or a Tour rest day in Pau.

I had gone for a pre-dinner stroll around the old town, taking in a performance of flag-waving and drumming put on by local children in medieval attire. (Should such a civilized event have taken place on a Saturday night in a similarly provincial town in England, it would have ended with a drunken brawl between youths using both flags and drums as weapons.) Bumping into Simon and Richard, we went for an Aperol spritz in the Piazza Garibaldi.

We ordered two of the bright orange concoctions – the same colour as Roddy’s vintage San Pellegrino top – plus a vodka and tonic for Richard. The waiter clearly got a little confused on his way inside, and swiftly returned to confirm the order. He arrived five minutes later with two Irn-Bru-evoking spritzes and a gin and tonic. Embarrassment was etched over his face when, for a third time, Richard asked for vodka. The gin was apologetically whisked away and swiftly replaced. Then, a few more minutes later, the waiter returned with a plate of sliced focaccia. We were the ones who now looked confused. Was this a kind gesture for having fumbled our order?

‘Given his track record, I reckon it’s probably someone else’s,’ I said.

‘I’m not sure if we should dig in. I half expect him to return and ask for it back,’ said Simon.

‘Before introducing us to his brother, a taxi driver just back from a massive detour to La Chalp,’ quipped Richard.

‘Ah, you ordered us an appetizer!’ Beer in hand, Terry plonked himself down in the empty chair with the usual litany of moans – the human equivalent of a rusty gate creaking on its hinges. He was with Sam, who bravely joined us four Brits for a pre-dinner drink. Through mutual reminiscing about ‘The Girl With The Butterfly Tattoo’ the subject of wives and girlfriends came up – and Simon threw into the ring the first genuine shock of the whole tour.

‘You know Tom Jones and Kay aren’t an item?’

‘Who’s Tom Jones?’ asked Sam, quizzically.

‘Wait, wait, wait,’ I said, ignoring Sam’s ridiculous question. ‘This is a lot to take on board. But first: Simon, I’m pleased – relieved, even – that you too think John looks like Tom Jones.’

‘Tom Jones?’ said Sam, still puzzled.

‘He is so Tom Jones,’ Simon giggled.

‘I know! I told the others in the first week but they just looked at me strangely. But what’s this about John and Kay not being together?’

‘Tell me you’re joking? You’ve been here since the start of the tour! You didn’t seriously think they were a couple, did you?’ Sam had a look of total bemusement on his face.

Richard was quick to jump to my defence: ‘But she’s a lady . . . And he’s a sex bomb . . . It’s an easy mistake to make.’

Talk about a bolt from the blue. It was like discovering Torvill and Dean weren’t performing open axels or triple Salchows with one another off the ice. From the outset I just presumed that Kay was John’s Delilah.

‘But they share a room, wear matching kits, ride together every day . . .’

‘Except they don’t ride together,’ said Simon.

‘That sounds familiar,’ said Terry, entering the fray with another sigh.

‘Come on – they must be getting it on,’ said Richard, before bursting out into song: ‘Da da-da, da da-da! It’s not unusual to have fun with anyone . . .’

‘Guys – you’re ridiculous. Both John and Kay have partners at home. They’re just good friends. I imagine they’re sharing rooms because it’s a damn lot cheaper,’ interrupted Sam, the voice of reason. ‘I booked all the accommodation and I can assure you that they have individual beds every night. And what’s it with Tom Jones? They don’t even look remotely alike!’

‘They so do,’ blurted Richard, before testing his baritone once again. ‘Why, why, why would you let your other half go on a month-long holiday in Europe with another person?’

He clearly wouldn’t let it drop – although it was bleedingly obvious that this whole imaginary charade couldn’t have been further away from, say, the real-life saucy antics of a certain Jacques Anquetil. The first man to win five Tours openly led something of a love rectangle between his wife, Janine, and her daughter from a previous marriage, Annie, with whom he himself had a daughter before fathering a son with Janine’s daughter-in-law, Dominique. Try getting your head around that after a few too many Aperol spritzes . . .

Thinking back at the many times I had insisted on taking photos of John and Kay together – ‘Come on, guys, get a bit closer!’ – I inwardly cringed at having got it so wrong.

A small pause in proceedings was followed by Richard breaking the ice with a rather uncouth query that had admittedly also crossed my mind. ‘I wonder what Tom Jones does when he needs a dump? It’s bad enough when you’re with your girlfriend or wife. But if you’re just rooming with a friend – a lady friend . . .’

‘That’s why I’m always so late to breakfast. I have to wait until Terry’s gone before I can settle down and see to my business.’

‘That’s kind of you, Felix. I’m afraid it’s always the first thing I do once off the bike.’

‘Yes, Terry. I know. I have to listen to the ordeal every day. I would cover my ears with an extra pillow, but they’ve always already been swiped.’

‘Oh, do you like to sleep with an extra pillow too? I am sorry . . .’

The after-shocks of the grand divulgement having subsided, conversation inevitably moved on to our own relationships – or lack thereof. Simon, the silverback of our group, said he was newly single following a fling with a young lady from one of his spinning classes. Previously he’d been in a no-doubt colourful long-term relationship with someone who, as a girl, had lived with and worked for the ever-so-creepy eighties comedy duo The Krankies. Simon also had three children from a previous marriage: two daughters in their twenties and a 19-year-old son who was a professional golfer.

‘He’s always been sporty. I remember he once picked up a javelin on sports day and – despite recovering from a broken leg – smashed the school record with his first throw,’ Simon said, adding with bogus self-deprecation: ‘He clearly gets it from his mother.’

After a slight contemplative pause Terry replied, matter-of-factly: ‘Oh, was she a javelin thrower?’

It was a classic Terry moment that had us all rolling in the aisles. What made it all the more hilarious was the total sincerity of his question. He started laughing along with us but had no idea why we found it funny. This incongruous naivety was at the complete opposite end of the spectrum to his usual over-the-top braggadocio where he – albeit egged on and aided by molto vino rosso – was in complete control.

Later on, during our meal around the block at La Duchessa, the best pizzeria in town, it was this side of Terry that he unleashed upon us. It was our first pizza since arriving in Italy and spirits were high. We ordered a whole range of different varieties and agreed to pick and choose along with some salads. To drink we had copious bottles of Barolo to which – now liberated from the yoke of our bikes – we could give our undying attention. Raising his glass of fizzy water, Bob proposed a toast to his wife, Sandy. ‘She says hello to everyone. It’s almost our forty-eighth wedding anniversary.’

‘Forty-eight years!’ exclaimed Terry. ‘You don’t get that long for murder. And at least in prison it’s solitary confinement.’ He downed his glass of wine, which Simon duly refilled.

‘I just don’t understand women,’ he said, the whole table on tenterhooks. ‘Mine’s only five foot two and she’s constantly beating me up. I have to leave the house just to get some peace and quiet.

‘It’s a constant struggle,’ he added, with a cheeky grin and the kind of twinkle in his eye that didn’t befit a man who was enduring any genuine hardship. ‘Felix,’ he addressed me as the first round of pizzas arrived. ‘Stay single. Don’t ever get married. Why would you ever want to put yourself through so much punishment?’

After taking a break for air – as well as some wine and a few slices of quattro stagioni – Terry shifted the subject on to more carnal matters, sharing rather a lot more information than you’d wager him offering were Dylan – or his wife, for that matter – present.

‘I can’t remember the last time we did it. Probably when Dylan was born. The more she deprives herself the more uptight she gets. And it’s crazy because it was the one thing we were always good at. She moans like hell that I don’t pay her enough attention. And when I do—’

‘She moans like hell?’

Simon’s comment had Richard in stitches. It was like watching The Goon Show perform live.

Meanwhile, Terry continued his improbable rant while tearing off a slice of truffle-oil-infused margherita.

‘You know, I’ve even offered to pay but she’s having nothing of it. Hahaha!’ (When in full showman mode, Terry rarely resisted the temptation of providing the canned laughter to his solo sitcom.) Terry’s subsequent declaration that he was contemplating divorce was proof enough that he was hamming things up for his baying audience. Towards the end of the trip he would eventually assure me in a moment of touching sobriety that, ‘I’m only pulling your legs – I’m very happily married really and wouldn’t get divorced in a million years. I have three amazing children, I’ve retired and now I’m a grandfather. What’s not to like? Look at Dylan – he’s the happiest man I know. And that only makes me happier.’

But back in Alba, Terry’s circus continued as we paid a visit to a nearby ice-cream parlour. My trio of strawberry, lemon and Champagne pink grapefruit was, I concede, rather camp – but the three generous scoops were at least united in their fruitiness. For Terry, the rules of flavour pairing went out the window. His was the most bizarre flavour trifecta known to man: liquorice, melon and Terrymisu. Even the girl behind the counter had to bite her tongue.

Outside, as we licked our gelati while taking in the tremendous window display of the local barber (which, alongside the omnipresent posters of George Clooney and Brad Pitt as seen in hairdressers the world over, contained a quite splendid shrine to 1970s perms, bouffants and facial hair fads), Terry drew his final conclusion from a night of inebriation.

‘I think I’m going to go gay for the next part of my life.’

Days later, I would catch him gazing at me during a pasta pit stop. ‘You’re really glowing today,’ he told me (and the rest of the table). ‘You’ve caught the sun and look very handsome.’ That same night, we arrived at our hotel to find just the one double bed in our room. Yikes – what if he was being serious?

The alarm shrilly sounded. It was still dark outside. Terry’s routine began in earnest: a shave and a succession of sobs and sighs from the shower; the noisy unpacking and repacking of his numerous plastic bags before the daily loading up of his camper’s backpack. At some point during this sorry sideshow I squinted at my watch. It was only 6.30 a.m. I rolled over with a groan.

‘Terry!’

‘Oh no, what have I done now?’

‘It’s still dark outside . . . look at your watch again.’

‘But I could have sworn I set it for half seven,’ he said, realizing his mistake. ‘Oh well, I’m up now. I might as well go and join Bob for breakfast.’

When I eventually stumbled downstairs to join the others the morning’s misery was further compounded by a babble of tourists gathering with stale intent at the breakfast bar. It was rush hour and a bottleneck of hungry Germans around the cheese and ham counter was causing minor mayhem. Expectations high after the bright orange yolks of the Castello Rosso’s sumptuous soft boiled eggs, breakfast at Alba’s Hotel I Castelli was a philistine experience: a return to packaged snacks and hot beverages delivered with deafening clangour via the single nozzle of a solitary machine.

With eight short but sharp climbs on the agenda, our second day in Piedmont was hardly the typical Sunday day of rest. An early setback saw me suffer the ignominy of stumbling on to the pavement of a town right in front of an old lady, who promptly burst into a fit of cackling. She continued to goad me as I fumbled with my chain, which had slipped off and wedged itself between the cassette and frame. Payback, perhaps, for those column inches spent taunting Andy Schleck about his infamous chain drop in the Pyrenees in the 2010 Tour.

It happened when Schleck launched an attack near the summit of the Port de Balès climb. Seeing the yellow jersey stutter to the side of the road, Alberto Contador pressed on with two others – later drawing scorn from Schleck, who claimed the Spaniard should have done the sporting thing and waited. Despite a frantic descent, Schleck came home 39 seconds behind Contador, who took the race lead. Contador admitted to the press afterwards that it was a ‘delicate situation’ but stressed his conviction that ‘30 seconds won’t change the race’. A week later, Contador rode into Paris in yellow to beat Schleck by 39 seconds.

‘My stomach is full of anger,’ the spindly Luxembourger admitted. When it later turned out that Contador’s own stomach was full of contaminated beef, it was Schleck, the resultant de facto winner, who had the last laugh.

Seeing me struggle, both Terry and Sharon took pity and, unlike Alberto, waited. We then snuck off for a coffee so I could wash my oily hands. The treat was on Terry by way of an apology for the early wake-up call. We indulged in some morale-boosting mini ice-cream pots – wild berry for Sharon, chocolate orange for me, and tiramisu (what else?) for Terry – before I sauntered into the market to replenish my snack pouch with a bag of wine gums.

The remainder of the final day of the second leg of the tour was largely uneventful compared to the significant revelations of the night before. I still felt mortified for having thought for so long that John and Kay were married, consumed by pangs of guilt for not having ascertained this through polite conversation. It was an honest mistake – and assuming they were a couple from the start, it wasn’t as if I was looking for evidence of the contrary. That, after all, would have been weirder than the misunderstanding in the first place. But it still took some getting used to. When I later spotted John answering a call of nature beside the road as Kay – wearing a matching Team Australia kit – kept watch, I had to forcibly remind myself that she was doing so not as doting wife but faithful friend.

My perplexed mind was thankfully distracted by a field of pigs mooching around in a huddle. Female pigs used to be integral to locating truffles in the region’s soil: the ingots of priceless pungency produce a chemical almost identical to a sex pheromone found in boar saliva (the same chemical, incidentally, that men secrete in their underarm sweat). Such is the power of their snouts, sows can sniff out these ‘white diamonds’ as far as three feet underground. But a law in 1985 banned the use of truffle hogs in Italy – primarily because of their natural porcine propensity to gobble up the prized nuggets as soon as they had trottered them out of the ground. In the absence of horny, hungry hogs on heat, truffle hunting went to the dogs – quite literally.

Obediently trained truffle hounds are now used – and in Italy, one particular breed sets the standard: the Lagotto Romagnolo. The curly-coated water dogs were duck retrievers until the draining of the northern marshes in the early twentieth century led to a decline in duck hunting and the end of the traditional role of these hard-working, cheerful mutts. But the Lagotto’s infallible sense of smell – coupled with their doggy disinterest in eating the fancy fungi – made them the ideal candidates to replace pigs in the cut-throat world of truffling. Prized truffle hounds can fetch up to £6,000 each at auction, making the Lagotto – the only pure-bred dog on the planet specifically recognized for its phenomenal truffling instincts – one of the world’s most expensive breeds.

The spa town of Acqui Terme welcomed us for lunch – a caprese salad and a plate of ravioli in the central square, a truffle’s throw from the octagonal pavilion underneath which a sulphuric spring bubbles out of the ground amid diabolical pillars of steam, scalding the hands of inadvisedly curious tourists. (Luckily there was some soothing hand cream for Terry in the bus.)

The Giro has come to Acqui Terme just twice, with an Italian winner on both occasions. In 1937 Quirico Bernacchi took the spoils days before contracting typhoid after drinking from a puddle. Eighteen years later, the race returned with victory for sprinter Alessandro Fantini who, the previous year, had famously finished a brutal stage in the Dolomites wearing a leather jacket for protection from the sub-zero temperature brought about by a freak snowstorm. Like many riders, Fantini had earlier hitched a lift in a car – a course of action (along with hot baths en route) actively encouraged by the desperate race officials to stem the rampaging tide of withdrawals. In fact, stage winner Charly Gaul, whose morose features made him a dead-ringer for Droopy the dog, was practically the only rider who eschewed motored assistance. ‘The Angel of the Mountains’ was in short sleeves as he turned his disproportionately stumpy legs up the snow-buffeted Monte Bondone to seize the maglia rosa on a day which, L’Équipe wrote, ‘surpassed anything seen before in terms of pain, suffering and difficulty’.

Four years after his victory in Acqui Terme, Fantini fractured his skull in a crash during the Tour of Germany. After tests in hospital, doctors concluded that the 29-year-old had suffered a brain haemorrhage moments before his crash. They couldn’t operate because of the high levels of amphetamines in his body. He died two days later. The moral of the story – as Lance Armstrong might say – is pretty clear: avoid wearing leather.

Towering over the ramshackle riverside town below, the imposing eighteenth-century fortress at Gavi can be seen from quite a distance and helped Richard and me find our bearings as we neared the completion of the stage. Both our Garmins had run out of juice and so we slowed to wait for our domestiques, Bob and Bernadette.

Before the second rest day and two successive nights of luxury in the peaceful Villa Sparina, one final obstacle: a rasping climb through dense woodland to the hamlet of Monterotondo – five minutes of sustained lactic-guzzling activity akin to ten lashes of the whip. With 1,700 kilometres now in the legs after sixteen consecutive days in the saddle, I rode clear of my companions to cement my place at the top of the standings. The pink jersey would stay on my shoulders heading into the final leg of our ride to Rome.

The delicious robiola risotto and braised beef combo that awaited us that evening was capped by generous bowls of home-made vanilla ice cream with a variety of toppings. Preceded by Italian breads, cured meats and ample aperitivos, it was a meal to guarantee a good night’s sleep. Terry and I even had the luxury of separate bedrooms in our plush living quarters, giving us both some welcome time apart (my tendency to stay up late working and rise in a foul mood must have tested Terry’s patience by now). We did, however, still share a bathroom – accessible only via my room – which led to a couple of heart-in-mouth moments as Terry traipsed past my bed in search of the loo, fumbling his way in the dark.

Shortly after my fifth slice of mortadella at breakfast the next morning our numbers were depleted by numerous deserters. Melbourne John and Roddy’s ten days with us were over, while long weekenders Simon and Richard had to return to the hustle and bustle of London. On a positive note, we would soon be buttressed by the select core of the hardened troupe of Sydney club riders entering the fray, alongside the welcome return of Dylan. Despite its early sedentary promise, my rest day was not entirely restful. There may have been nothing as appealing as the Ventoux on the horizon, but I was still eager to keep the legs turning – even if I stopped short at putting in a full hundred klicks.

While most of our group chose to mooch around the narrow, cobbled streets of Gavi during the day, Bob and I opted to stay back at the hotel and take it easy: he to do some outdoor reading (a few chapters of Edgar Allan Poe, no doubt, washed down with a carton of orange juice) and me a little work on the veranda. As we later grazed on a light lunch of mushroom tortellini and steak tartare on the terrace overlooking the villa’s vineyards, I was tempted to ditch my riding plans – especially after a glass of sweet and musky Asti Spumante, the local sparkling wine. But having returned to my room for a snooze, my limbs were stirred by the scenes playing out in the courtyard below, from where a series of cries and expletives came as a slowly increasing number of fatigued figures gathered on bikes.

‘Jeez, that last bit was hard as.’

‘My legs turned to shit on the sixth ramp.’

‘D’you see Dave? The fat fuck blew to pieces before the first bend.’

‘Pete, who won? Please tell me it wasn’t the frigging dead possum again . . .’

The Velosophy splinter group being chaperoned by Dylan had arrived with a typical jejune Antipodean swagger. Evidence of their exertions forced me up and into my Cinzano top and lime-green shorts. Creeping out the back door to avoid any confrontation, I set off for a 30-kilometre cruise towards the nearby town of Novi Ligure – a place that is to Italian cycling what sick pilgrims are to Lourdes.

Home of ‘The Novi Runt’ Costante Girardengo, the bustling town boasts a museum dedicated to the diminutive rider and his fellow Italian great, Fausto Coppi. Back in his heyday in the 1920s, Girardengo was the first cycling star to be declared a campionissimo – or champion of champions, the nickname now usually associated with Coppi. If, as was claimed, Girardengo was more popular in Italy than Mussolini, he certainly wasn’t doing the prime minister any favours in his bid to get the nation’s trains running on time: such was the public esteem towards the nine-time national champion, it was decreed that all passing express trains should stop in his home town – an honour usually reserved for heads of state.

For his part, Coppi was brought up in nearby Castellania, leaving school at the age of 13 to work for a butcher in Novi Ligure. On top of the 15-kilometre ride to and from work, Coppi spent most of his days delivering salamis and prosciutto on his bike before being taken under the wing of a former-boxer-cum-cycling-masseur who was a regular at the delicatessen. When he won his first race at the age of 15, Coppi’s reward was 20 lire and a salami sandwich – a bit of a rubbish prize considering he spent his days couriering the damned things in his knapsack. Bradley Wiggins – here’s your prize: a pair of fake sideburns! The advice given to Coppi on his professional debut in Tuscany in 1939 was clear: ‘Follow Gino Bartali!’ That he did throughout his career until, in a spray of Perrier on the Galibier, he eventually surpassed the one other Italian rider with a claim to true campionissimo status.

Marble busts of both Girardengo and Coppi are on display outside Novi Ligure’s Museo dei Campionissimi – the largest bike museum in the world. This being a quiet mid-September Monday afternoon, the museum was shut and my plans for a spot of culture derailed. Instead, I rode the undulating road back to Gavi and tackled the crazily steep lane up to the fortress to watch the sun set over the jagged horizon. This extra uphill excursion to the last Napoleonic stronghold in northern Italy meant I had to forgo a tour of the Villa Sparina wine cellars while I freshened up for dinner. Having already enjoyed the culinary wizardry of the hotel kitchen, we conceded our table at the restaurant to the animated Velosophy gang while our streamlined team of seven stalwarts – Bob, Bernadette, Terry, Sharon, John, Kay and myself – headed back to Gavi with Sam to eat in what appeared to be the only open establishment. Tough and sinewy, my bone-heavy rabbit stew boasted about as much flesh as a braised leg of Chris Froome, while the accompanying broccoli had clearly been on the boil for as long as Froome’s trigger-happy girlfriend, whose Twitter spat with Mrs Wiggins during the 2012 Tour made ripples in the pages of the Daily Mail. As we ate, Sam filled us in on the Carthaginian army’s early movements in northern Italy.

Around 70 kilometres north of Novi Ligure, Hannibal’s march on Rome had entered a new dawn. News of the Taurini massacre had spread like wildfire. Still leading his own troops towards the Po after having set sail from Marseille, the Roman consul Publius Cornelius Scipio was perplexed at the alacrity of Hannibal’s Alpine crossing. For his part, Hannibal was equally baffled that Publius’s army had made their round trip so quickly.

But spare a thought for the people of Rome, who were still under the illusion that both armies were in Spain. Imagine the bewilderment and alarm of the Senate on discovering that Hannibal had not simply crossed Europe’s largest natural barrier, but had routed the Roman army in battle at the river Ticinus, a tributary of the Po.

For this is indeed what happened when the two sides finally came head to head on Italian soil. Before the confrontation, Hannibal had roused his men through novel means: offering certain Gallic prisoners the chance of freedom through various bouts of armed combat among themselves. Think of it as a grown-up version of The Hunger Games for the second century BC. Hannibal felt his men would better understand the challenges ahead by watching the suffering of those they had already conquered. You could say that I was working along similar lines of motivation on deciding to get off my arse and start cycling some of the routes tackled by the professionals – although I was not in the habit of strangling Bob with an inner tube or cleating Bernadette to death.

Just before leading his men into battle, Hannibal called them together for some final words of encouragement. He then hoisted up a lamb in one hand and, uttering a prayer to the gods, dashed the animal’s brains out with a stone; a sacrifice that would have got the thumbs-up from bon viveur Jacques Anquetil, who famously spent the rest day of the 1964 Tour stuffing his face with barbecued lamb at a VIP party in Andorra. The next day Anquetil’s form was so woeful, the defending champion was dropped on the first climb. At the summit, his directeur sportif gave him a make-or-break bidon of Champagne in a bid to clear his indigestion. It worked. ‘Maître Jacques’ caught up with his principal rival Raymond Poulidor and stayed on course for a record fifth win.

There was no Champagne but you can imagine Hannibal granting his army extra rations of sour wine following their rousing victory at the Ticinus. The swift-moving Numidian horsemen were the stars of the show, making up for their poor performance at the Rhône and doing a Richie Porte-esque job for their team leader. To make matters worse for the Romans, Publius was badly wounded and would have died were it not for a last-ditch rescue by his 17-year-old son, the future Scipio Africanus, the man who ultimately proved to be Hannibal’s nemesis.