It might well be assumed that as the French government had taken the initiative in declaring war, it had done so with a clear intention of what its armies would do. In fact, other than a vague objective of meeting the Germans in the field and defeating them, in all the discussions as to whether or not to declare war, the politicians had not considered what they expected the Army actually to do. Given the known fact that Germany could mobilize about one million men against, at best, 300,000 French troops, France’s only advantage would be a brief one, that is, in having a standing army rather than a force requiring the calling up of reservists, it could strike first. Instead, while von Moltke’s careful pre-war planning successfully mobilized, equipped, and assembled more than one million men within eighteen days of the declaration of war, the French effort was shambolic. Even when assembled the French forces were to lack any clear strategic direction while German forces were to surge forward with carefully planned objectives. As it was, impatience and insubordination on the part of certain senior German commanders was to be the only significant spoke in Moltke’s wheel. It was this, rather than any French initiative that presented a number of opportunities for French success; all were to be studiously ignored by the French command.

During the previous eighteen months Moltke and the German Staff had drawn up a detailed plan for an offensive war against France: using detailed maps of eastern France which not only included the smallest road but the number of inhabitants of every town and village, a comprehensive timetable of assembly and invasion was refined. Here the General Staff came into its own for these were professional advisers, not mere adjutants, being selected each year from the outstanding graduates of the Kriegsakademie. Moltke had defined their role as the study of the conduct of war in peacetime and to provide information and advice to commanders in the field during war. They were trained to assess what action was possible within the limits imposed by the technical difficulties of communication and supply. Basically, the General Staff was the Army’s nervous system, giving its movements coherence and flexibility. Its specialist transport and logistics officers produced detailed train time-tables that would deliver hundreds of thousands of reservists to regional assembly points. Here they would find their equipment and details of the location of their parent regiment and a ticket for the train that would get them there. During this mobilization phase all rail traffic in Germany was subject to the direction of the General Staff. Further, in the post-mobilization phase, careful planning went into the re-supply of the assembled armies once in motion, although here they under-estimated the ammunition needs and only the relatively low expenditure prevented a crisis. Further, the wagon-trains needed to carry supplies from the railheads to field units proved less than perfectly organized and many supply trains had to search for their units, while they in turn had perforce to live off the land.

In fact, even before war was declared, the Prussian military attaché in Paris had informed the king on 11 July of discreet French preparations for war, and within twenty-four hours German plans were ready for issue. With the French declaration of war, Bismarck immediately invoked the secret clause of the Treaty of Prague requiring the four southern German states to join with the North German Confederation, which they did. Within eighteen days 1,183,000 men had been assembled and 462,000 transported to the French frontier.

Trooper, Prussian 4th Uhlan Regiment. The cavalry on both sides played little part in the battle on the 18th, the expection being the illfated regiments of the 1st Cavalry Division, directed to charge suicidally across the Mance Ravine. The Uhlans worn the sharply cut ulanka tunic and the traditional czapska headdress, although the latter was fitted with a black oilskin cover on campaign, with riding breeches and boots replacing leather-lined overalls. Illustration by Les Still.

Bavarian jägers. Although apparently still independent, the South German states were bound by secret clauses of the Nikolsburg Treaty to enter the war on the side of the North German Confederation. While retaining their national uniforms, they had, since 1867, re-organized their armies along Prussian lines and easily integrated into Third Army. (Illustrated London News)

Deployed in a wide arc between the Moselle and the Rhine were the Guard Corps, eleven army corps of the Confederation, the Royal Saxon Corps, two Bavarian army corps and a division each of Wiirttemburg and Baden, with 1,194 guns, pioneers, bridging companies, supply, medical services and other auxiliary services, all of which were divided between the three armies. First Army, composed of VII and VIII Confederation Corps, was concentrated around Wadern with the objective of striking through Saarlouis to the Moselle, south of Metz. Second Army, composed of the Guard, III, IV, IX, X and XII Corps, was in the centre, opposite Saarbriicken with the objective of the upper Moselle between Metz and Nancy. Third Army, composed of V and XI Confederation Corps, the two Bavarian corps and the Baden and Wiirttemburg divisions, were concentrated around Landau with the objective of striking through Wissembourg to capture Strasburg. Essentially Moltke’s strategic plan was to draw the main French Army forward on to Second Army and then encircle and destroy it, the objective being the conquest and occupation of Alsace-Lorraine.

All that remained was to appoint the senior Army Commanders and it was here that the human factor, the greatest of imponderables, came into play to disrupt Moltke’s careful planning. Command of First Army went to the 74-year-old Steinmetz because of his brilliant handling of a corps during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Moltke had many misgivings about this obstinate and insubordinate veteran and, over the next two weeks, his fears were to prove well-founded.

Command of both Second and Third Armies went to royal princes, the King’s nephew Prince Frederick Charles taking Second Army and the Crown Prince of Prussia, Frederick William, Third Army. Of these two, Frederick Charles proved unpredictable and over-cautious while Frederick William proved both competent and able to follow Moltke’s directions. Finally, it ought to be mentioned that Moltke not only had to contend with flawed army commanders, but he and his highly professional Staff found the Royal Heaquarters almost over-run with non-military personnel. There were numerous princes with their courts, a large corps of press correspondents from across Europe, to say nothing of King William and Bismarck’s own respective ‘assistants’.

Compared to the smooth professionalism of the Germans, French mobilization was grotesquely deficient. The man responsible for mobilization and deployment was General Edmund Leboeuf, Minister of War since the death the previous year of Marshal Niel. While not lacking talent and ability, Leboeuf was unquestionably complacent about France’s degree of preparedness. He has gone down in history for his assurance to the Assembly on 14 July, that ‘We are ready, very ready, down to the last gaiter button.’ In fact, nothing could have been further from the truth. On 14 July the actual order for mobilization was issued, directing reservists to report to their regiments and for regiments to move up to the frontier. Despite several warnings over the previous years from such officers as General Trochu that no planning or preparation had gone into this vital phase, until 8 July almost no thought had been given to the practicalities of this massive movement of men and matériel on the French railway network. While thousands of reservists struggled to get to their respective regiments’ depots and then move on to join their regiments, the self-same regiments had to leave their garrisons for the concentration areas at the frontier while their supplies had to be dispatched from central magazines to the depot and then on to the regiment. In early July only thirty-six of one hundred regiments of the line were based at their regimental depot. The 86th Regiment of the Line, for example, were in garrison at Lyon, while their depot was in Ajaccio in Corsica.

The chaos of this merry-go-round was further confounded by the intervention of Napoleon. Back in 1868 General Frossard had produced a very competent plan for the deployment of the Army in purely defensive positions on the frontier around Saarbrücken, but the heady days of July in Paris demanded something more dramatic than a defensive posture along the Palatinate. Having spent the period 8 to 11 July preparing corps concentration orders based on Frossard’s plan, Napoleon ordered a total reorganization so that he could take personal command of the Army and launch it on an assault of the Rhineland. Part of this optimism was based on the grossly misplaced assumption that the southern German states would remain neutral and that Austria would enter the war on France’s side. By the time Napoleon realized that Austria would not enter the war and that the southern German states would (on the side of the Confederation), it was too late to restore Frossard’s plan.

The nominal French equivalent of Moltke’s General Staff barely rose above a collection of adjutants and clerks selected almost at whim and given no special training. A year before, Marshal Niel had identified the need for qualified and trained officials to be given strategic control of the entire railway network so that reservists, regiments and supplies could be effectively shunted around the system. Nothing in the event was done to effect this, and instead local officials had to book trains in competition with normal civilian traffic and forward these trains to vaguely designated corps concentration areas. The result was that by day 23 of mobilization, 6 August, as the first armed clashes began, only 50 per cent of the reservists had reached their parent regiments and some did not arrive until the battles around Metz and Sedan four weeks later. Many who did reach their units did so without uniforms or equipment. Furthermore, for regiments the question of supplies often became desperate. While ample stocks of equipment, ammunition and food existed, all too often they arrived late or not at all and some formations were forced to requisition bare necessities from the locality. For example in Metz on 28 July there were only thirty-six bakers to provide bread for more than 130,000 troops. Later in the campaign the Germans were to capture vast quantities of French supplies from trains trapped in the clogged rail network.

Despite the complete reorganization ordered by Napoleon on 11 July, the concentration of the Army on the frontier between Luxemburg and Switzerland took place much as had been planned in Frossard’s original 1868 plan. This had envisaged the formation of three armies based on Metz, Strasburg and Châlons commanded respectively by Marshals MacMahon, Bazaine and Canrobert; Napoleon’s decision of 11 July demanded that there be only one army — the Army of the Rhine — composed of eight corps and lead by the Emperor in person. The three ‘dispossessed’ Marshals were to be compensated by extra-large corps: MacMahon received I Corps, Bazaine III and Canrobert VI.

Inevitably this juggling created further confusion and produced unbalanced corps as Leboeuf had no option but to improvise. In Alsace, I, V and VII Corps assembled, of which the latter two were new formations. West of Alsace, the Guard, II, III and IV Corps assembled, all of which, being pre-existing formations, were tactically fairly well-balanced. Finally there was VI Corps, an entirely new and improvised creation to provide the general reserve, which was gathered at Châlons.

Chasseur à Pied, 9th Battalion. While the specialized arms and role of the chasseur battalions had disappeared with the general adoption of the breech-loading rifle, their uniforms were distinguished from those of the line regiments. Rather than the greatcoat, in general they continued to wear on campaign their coats with blue pointed cuffs and collar piped in yellow, as were the kepis and blue trousers. The brass buttons bore the battalion number within a buglehorn.

As the formations gathered in late July, the question of what to do with the Army of the Rhine fell largely on the shoulders of Leboeuf as Minister of War. He was acutely aware that Moltke and Roon’s military machine could mobilize up to 1,000,000 men by early August against at best 300,000 French troops and so was conscious that time was of the essence. (In fact, by 28 July, the fourteenth day of mobilization, only 202,448 were recorded as being with the colours.) As he departed Paris for the Army Headquarters at Metz on 24 July, he felt it vital that all eight corps should advance towards the German frontier, regardless of the fact that many units were far from complete, and the corps were strung out over a front of one hundred miles from Luxemburg to Wissembourg. Leboeuf intended that the Army concentrate and thrust into the Palatinate, hoping that the taking of such an initiative would disrupt German troop concentration and draw Austria into the war. But before Leboeuf could initiate his offensive Napoleon arrived at Metz on 28 July, having left the Empress as titular head of a Regency Council in Paris. He immediately countermanded Leboeuf’s plans, feeling (with some justice) that the Army of the Rhine was unready for any sort of offensive. Instead, the Army was held in position while Napoleon, subject to increasing indecision and rumour, wondered what to do. Before any decision could be made, on 30 July Moltke made it for him, the Army of the Rhine then numbering 238,188 men against 462,000 available to Moltke.

Possibly one of the most able French commanders was Marshal Patrice MacMahon, Duke of Magenta. His distinguished record in the Crimea and Italy ensured high command and despite defeat at Fröschwiller-Wörth and Sedan, few blamed him for the impossible situation in which he found himself. After the war he went on to become the Second President of the Third Republic, having put down the Paris Commune in 1871. (ASKB)

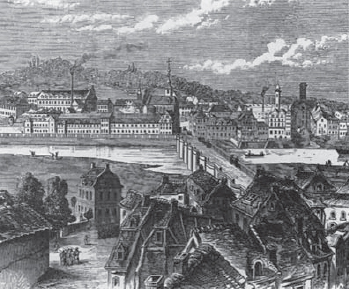

Saarbrücken. The seizure of this Rhenish town on 2 August was the limit of the much heralded French offensive. After an occupation of less than four days the town was evacuated as the Army of the Rhine began its long retreat. This was not before the French public and press had convinced itself that its seizure proved victory was all but theirs. (Illustrated London News)