Background to war

Home of the wolf

We are free and equal, like wolves.

– Chechen saying

The national symbol of the Chechens, visible everywhere from badges and knife pommels to the flag of the independent ‘Chechen Republic of Ichkeria’ – Ichkeria is the traditional Turkic name for the region – is the wolf, borz in Nokhchy. Chechen folklore stresses the wolf’s role as both loner and pack-member and this duality is visible in Chechen society, too. It is traditionally dominated by the tribe and the clan (teip), each being made up of lines (gars) and families (nekye), governed by the male elders who interpret the adat, traditional law. While the adat and the collective wisdom of the elders are important, though, these are forever in tension with an egalitarian, competitive and aggressive spirit of adventure and independence.

The flag of the independent Chechen Republic of Ichkeria has a green background to symbolize the state’s Islamic roots and also as a representation of life. The red stripe stands for the blood shed in the name of freedom and the wolf on the state coat of arms is a traditional Chechen symbol. (Public domain)

To the Chechens, after all, the wolf symbolizes courage and a love of freedom, but also implicitly a predator’s spirit. Traditionally, Chechen culture was a raiding one, in which young men would prove themselves by raiding other tribes and teips – even ones with whom they were on good terms – for horses or cattle or even brides. These raids, which were meant to be essentially bloodless (although a raider caught by his intended victims might face a good beating before being released or ransomed), were also ways of maintaining the skills that would make the Chechens formidable guerrillas. Killing another Chechen would simply bring blood feud from his kin; the feud is a powerful force in such a society, and in some cases ran from generation to generation.

Historically the Chechens have thus been politically fragmented but culturally united. While sharing the same language, identity and traditions, individual tribes and teips essentially managed their own affairs, except when some common enemy threatened. Then they would typically unite behind some charismatic warlord, such as Imam Shamil in the 19th century and Dzhokhar Dudayev in the 21st, to break apart once again when the conflict was over or the leader had fallen.

The only good Chechen is a dead Chechen.

– Attributed to General Alexei Yermolov, 1812

Traditionally, Russian attitudes towards the Chechens have been complex, a mix of fear, hatred and respect. In the main, the Russians have considered the gortsy, the ‘mountaineers’ as they sometimes call the peoples of the North Caucasus, to be generally untrustworthy, wily yet primitive. However, the Chechens assumed a special place in the 19th-century Russian idea of the Caucasus, sometimes the noble savage, often just the savage. Mikhail Lermontov’s Cossack Lullaby, for example, includes the lines ‘The Terek runs over its rocky bed./And splashes its dark wave;/A sly brigand crawls along the bank;/Sharpening his dagger’ while in the song the Cossack mother reassures her child that ‘your father is an old warrior; hardened in battle’. There was something different, something alarming about the Chechens. To a considerable extent this reflects the tenacity, skill and ferocity with which they have fought against Russian imperialism since the earliest contacts.

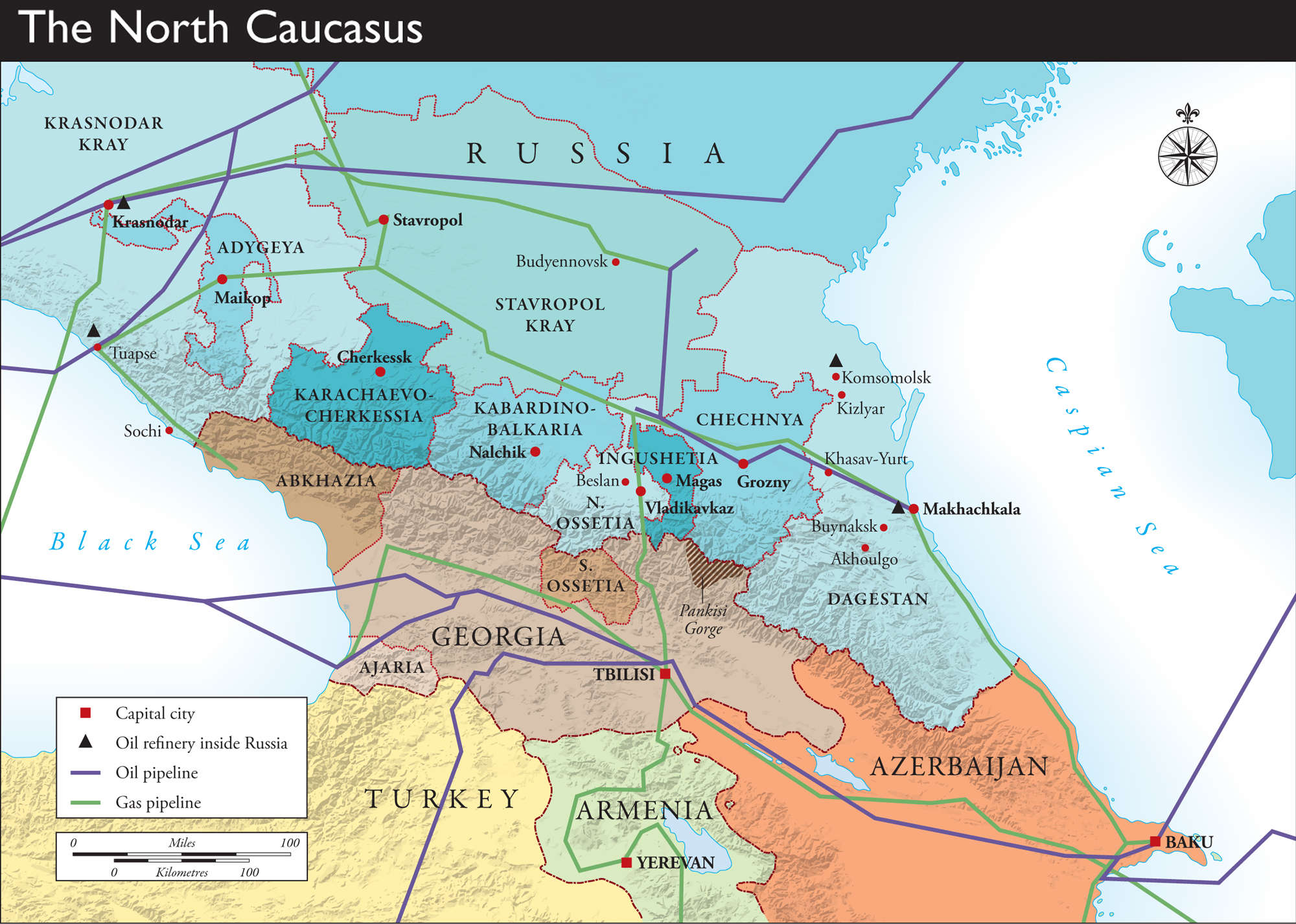

Although Cossack communities, seeking an independent life outside Tsarist control, settled in the North Caucasus as far back as the 16th century, it was really only in the 18th century that the Chechens and the Russian state encountered each other. There were skirmishes during Peter the Great’s 1722–23 Caucasus campaign against Safavid Iran that showed that the Chechens in their home forests were not to be taken lightly, but it was the struggle against Sheikh Mansur (1732–94) which began in 1784 that truly alerted the Russians to the threat they faced. A Chechen Muslim imam, or religious leader, educated in the Sufi tradition, Mansur was angered by the survival of so many pre-Islamic traditions within Chechnya and campaigned for the universal adoption of sharia Islamic law over the adat. He declared a holy war – jihad or, in the North Caucasus, gazavat – initially against ‘corrupt Muslims’ who did not recognize the primary of sharia and, coincidentally, his own authority.

This was an essentially domestic issue, but Mansur’s message became increasingly popular across the North Caucasus as a whole and followers of other ethnic groups began flocking to his cause. When the Russian authorities heard that he was planning to invade neighbouring Kabardia to spread his word, and even opening negotiations with the Ottoman Empire, they became alarmed. The Ottomans were the Russians’ main rivals along their southwestern flank, and Mansur’s holy war could easily and quickly be turned against Orthodox Christian Russia. Contemptuous of Mansur’s ‘scoundrels’ and ‘ragamuffins’, the Russians sent the Astrakhan Regiment into Chechnya, to Mansur’s home village of Aldy. Finding it empty, they put it to the torch, handing Mansur perfect grounds to declare gazavat against the Russians. Ambushed by the Chechens at the Sunzha River crossing as they marched back, the Russians were massacred: up to 600 were killed, 100 captured and the regiment disintegrated, individuals and small groups hunted down as they tried to flee through the woods.

Tsar Peter the Great (1672–1725), depicted in an 1838 work by Paul Delaroche (1797–1856). Although Peter the Great is best known for building St Petersburg and his European military adventures, his Azov campaigns against the Ottoman Empire (1695–96) continued a drift to the south in Russian imperial expansion that would bring them into collision with the Chechens. (Public domain)

Buoyed by this success, Mansur gathered a force of up to 12,000 fighters from across the North Caucasus, although Chechens were the largest contingent. His skills were as charismatic leader rather than strategist, though, and Mansur made the mistake of crossing into Russian territory and trying to take the fortress of Kizlyar. Fighting the Russian Army on its own terms and in its own territory, Mansur’s forces were routed. Although Mansur would remain active until his capture in 1791, whenever he took the field against the Russians, he lost. Even so, he had demonstrated that the Chechens could be formidable when united against a foreign enemy and fighting their own kind of war.

Hitherto, though, Chechnya had been considered something of an irrelevance, a land rich only in troublesome locals. The real prize was Georgia to the south, and the real enemies were Safavid Iran and the Ottomans. When Georgia was annexed in 1801, secure routes to Imperial Russia’s newest possession began to matter. Once Russia found itself at war with both Iran (1804–13) and the Ottoman Empire (1807–09), then the need to shore up the Caucasus flank meant that St Petersburg finally decided it was time to extend its rule in the North Caucasus.

The chosen instrument was General Alexei Yermolov, an artilleryman who had distinguished himself during the war with Napoleon and who was made viceroy of the Caucasus. He set out to subjugate the highlands by a policy of deliberate, methodical brutality. His strategy was to build fortified bases and settlements across the region, to bring in Cossack soldier-settlers and to respond to risings and provocations with savage reprisals. Infamously, he affirmed ‘I desire that the terror of my name shall guard our frontiers more potently than chains or fortresses.’

Yermolov was especially wary of the Chechens, whom he considered ‘a bold and dangerous people’. He founded the fortress of Grozny in 1818 – the name means ‘Dread’ – as a base from which to control the central lowlands. His aim was to pen the Chechens in the mountains, clearing the fertile lowlands between the Terek and Sunzha rivers for Cossack settlers. They in turn would cut down the forests that gave the Chechens such an advantage. In 1821, the Chechens held a gathering of the teips to unite against the Russians; Yermolov responded with a campaign to drive the Chechens into the highlands with fire, shot and sword. Even so, the Chechens were beleaguered but not beaten. In a sign of things to come, terrorism and assassination began to supplement raids in their tactical repertoire. In 1825 two of Yermolov’s most notorious officers, Lieutenant-General Dmitri Lissanievich and Major-General Nikolai Grekov, died when an imam, brought in for interrogation, produced a hidden dagger and stabbed them both. The Russians executed 300 Chechens in reprisal.

This portrait of General Alexei Yermolov (1777–1861), painted by British artist George Dawe (1781–1829) while Yermolov was still viceroy of the Caucasus, captures the man’s determination and obdurate ferocity. (Public domain)

In 1827, Yermolov was recalled and removed, the victim of court politics rather than as a result of any discomfort about his methods. His successors followed broadly similar policies, albeit with less ruthless enthusiasm. However, the next phase of the Russo-Chechen conflict would instead be initiated and defined by the ‘mountaineers’, specifically Imam Shamil (1797–1871), a Dagestani who raised the North Caucasus in rebellion and who remains a cultural hero for the Chechens to this day.

Recent accounts of the storming of the small, stone-hewn mountain villages, once the artillery bombardment had lifted and it became a question of close-quarter combat, are uncannily reminiscent of tales of taking fiercely held Chechen villages in the 19th century, including the 1832 assault on Gimri represented in this 1891 work by Franz Roubaud (1856–1928). (Public domain)

Shamil was a fighter as well as a religious figure, the de facto moral leader of the scattered ‘mountaineer’ resistance movement from 1834. At first, he tried to come to terms with the Russians, offering to accept their sovereignty and end raids on the lowlands, in return for a degree of cultural and legal autonomy. Major-General Grigory Rosen – who in 1832 had led a force of almost 20,000 troops across Chechnya, systematically burning crops and villages – rejected any thought of compromise. In part, this was precisely because the Russians feared the Chechens. In 1832, one officer admitted that ‘amidst their forests and mountains, no troops in the world could afford to despise them’ as they were ‘good shots, fiercely brave [and] intelligent in military affairs’. Lieutenant-General Alexei Vel’yaminov, Yermolov’s chief of staff, noted that they were ‘very superior in many ways both to our regular cavalry and the Cossacks. They are all but born on horseback.’

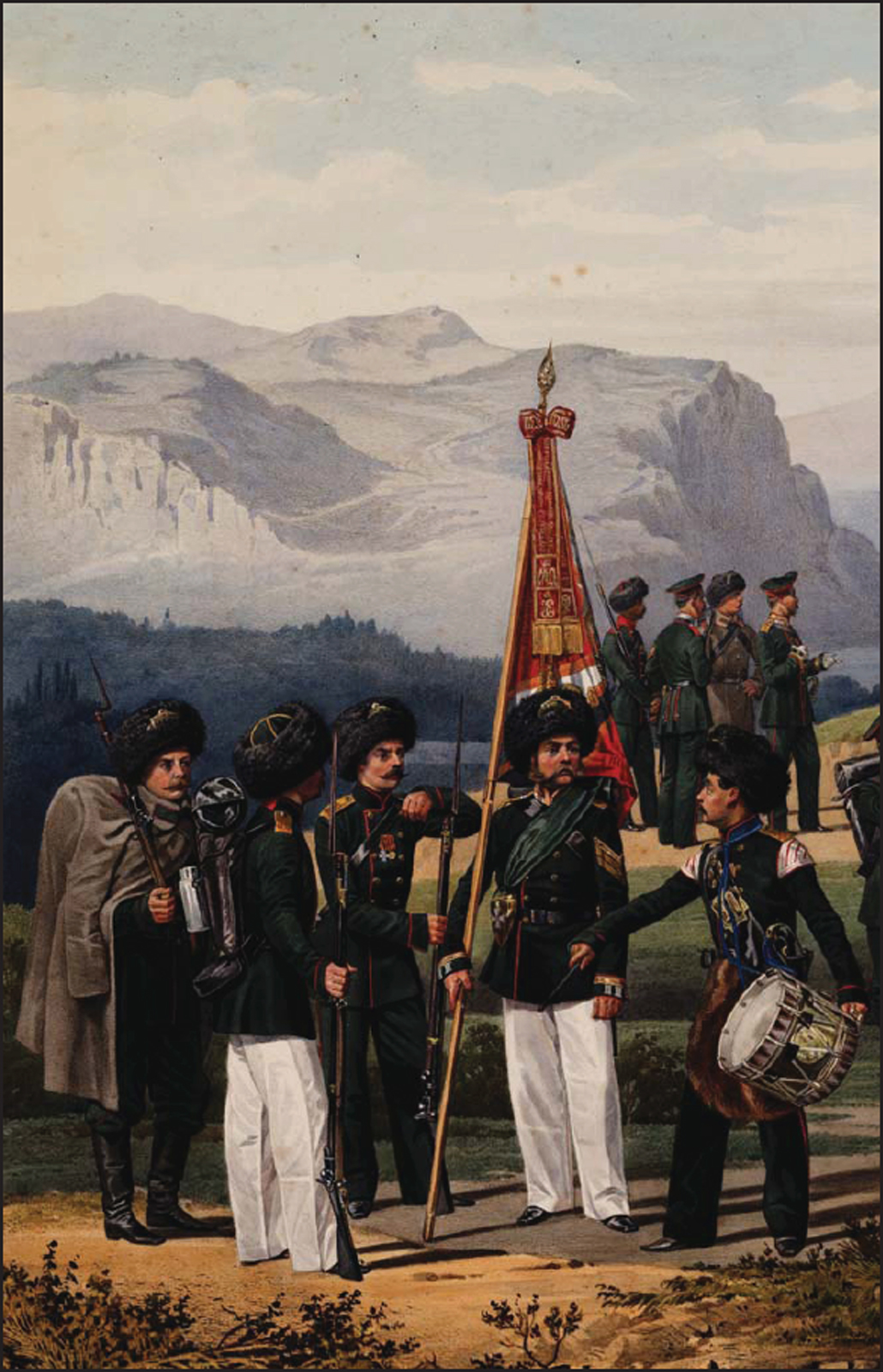

Detail from Infanterie de l’Armée de Caucase (1867), a hand-coloured lithocolour plate from an original by Piratski and Gubaryev, showing Russian and Cossack infantry officers and men from the Army of the Caucasus. Service in the Army was deemed one of the more arduous and dangerous postings in the Tsarist military. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

The Russians, thinking themselves on the verge of victory, simply increased the pressure. In 1839, Shamil only barely managed to escape when besieged for 80 days at Akhoulgo. The Russians took some 3,000 casualties before eventually storming this fortified village. However, they overplayed their hand and tried to implement a range of policies, meant to quash Chechen spirits once and for all. They only managed to rekindle the rising. Pristavy, government inspectors recruited from local collaborators, were given wider powers, which they typically used to persecute and plunder. Lowland Chechens were forbidden to have any contact with their upland relatives – or even sell them grain, one of their main sources of income. Then the Russians tried to disarm the Chechens, confiscating weapons which were seen as the main accoutrements of manhood and were often cherished family heirlooms.

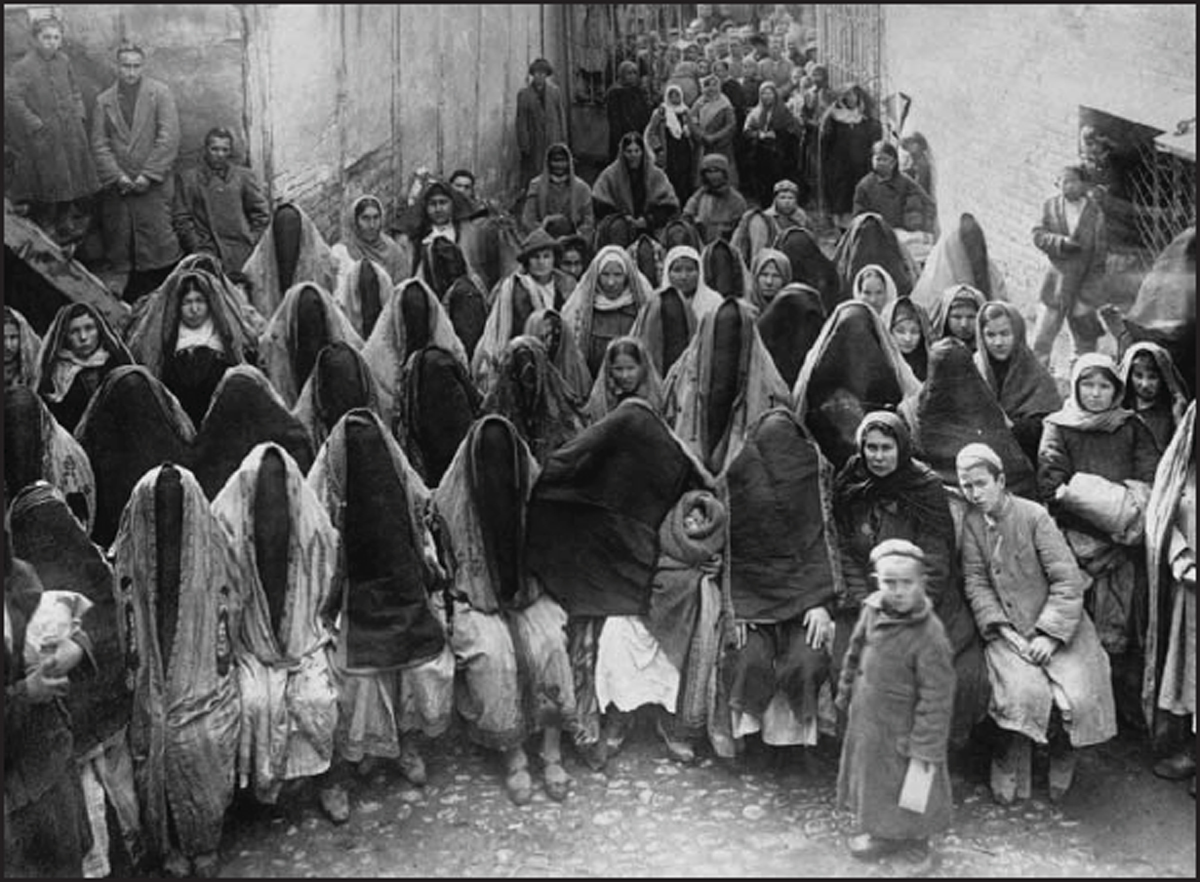

This undated photograph from the early Soviet era shows Muslim women crowding a street in the Caucasus region to listen to a Communist speaker delivering a speech on Soviet doctrine. This was presumably staged for the camera, as the Bolsheviks had relatively limited success in spreading their message in the region. (© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS)

Shamil combined Mansur’s charisma with rather greater military acumen. He raised the North Caucasus in a rebellion characterized by guerrilla attacks rather than set-piece battles in which Tsarist discipline and firepower could prevail. In 1841, General Yevgeni Golovin – who had previously quelled a Polish uprising – warned that the Russians had ‘never had in the Caucasus an enemy so savage and dangerous as Shamil’. Ultimately, though, he would fail. It was perhaps inevitable when set against the whole weight of the Russian Empire. After the end of the Crimean War in 1856, the Russians were able to deploy fully 200,000 troops to the Caucasus. In 1859, Chechnya was formally annexed to the Russian Empire and Shamil was captured, whereupon he was treated as an honoured prisoner. He was brought to St Petersburg for an audience with Tsar Alexander II before being placed in luxurious detention first in Kaluga and then Kiev. In 1869 he was even permitted to make the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and he died in Medina in 1871. In an irony of history, while two of his four sons continued to fight in the Caucasus, the other two would become officers in the Russian military.

The backward Dagestani and Chechen masses have been freed from the cabal of the White Guard officer class and the lies and deceptions of parasitic sheikhs and mullahs.

– Bolshevik statement, 1921

The Chechens were not to be pacified for long, and generation after generation rose against Russian rule, only to be beaten back down. Despite initial hopes that the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and subsequent Bolshevik take-over would mean their freedom, the Chechens found that the Soviets simply followed in their imperial predecessors’ footsteps. A Union of the Peoples of the North Caucasus was founded in 1917 and formally declared the independence of the region in 1918. During the Russian Civil War (1918–22), they found themselves clashing with White – anti-Bolshevik – forces under General Anton Denikin. The Whites were pushed out of the Caucasus in 1920 largely by Chechen and other forces – Denikin himself called the area a ‘seething volcano’ – and when they arrived, the Bolsheviks were greeted as liberators. However, nationality policy and the Caucasus campaign lay in the hands of an ambitious and uncompromising Bolshevik by the name of Joseph Stalin. He was not inclined to dismantle Russia’s empire and in 1921, the Mountaineer Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Gorsky ASSR) was established, subordinated to Moscow. Already, though, Russian insensitivity and Bolshevik attempts to supplant Islam had triggered a new rebellion, which lasted for around a year. Over time there were various territorial reorganizations – in 1924, the ASSR was divided into various districts and regions – but in essence, one imperial master had been replaced by another.

The short-lived Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic or Gorsky ASSR was founded in 1921 as the Bolsheviks sought to consolidate their grip on the North Caucasus. In a sop to local sensitivities, it combined Bolshevik red with Islamic green, with one star for each constituent region. It was progressively dismembered and formally abolished in 1924. (Public domain)

In the name of administrative efficiency and state control, in 1934 Stalin – now General Secretary and unquestioned ruler of the USSR – arbitrarily merged the Chechen and Ingush Autonomous Regions into one. The Chechens rebelled again and again were crushed. However, Stalin never forgot a slight. In 1944, concerned that the Chechens might again rise while the Soviets were locked in conflict with Nazi Germany, he decided on a characteristically dramatic solution. Near enough over a single fateful night, 23 February, the entire Chechen population of 480,000 was deported in Operation Lentil. Up to 200,000 died in what the Chechens often describe as the Ardakh, the Exodus. Resettled and scattered across Central Asia, Siberia and Kazakhstan, the Chechens were only allowed to return to their homeland in 1956, after Stalin’s death.

Vladimir Putin confers with military officers at a ceremony in February 2000 to commemorate the victims of Stalin’s brutal mass deportations from the Caucasus. Moscow’s efforts to shed this legacy have been difficult and many Chechens still compare Putin and Stalin. (© Antoine Gyori/Sygma/Corbis)

There would be no more risings, but Mikhail Gorbachev’s liberalizing reforms in the 1980s allowed the Chechens to campaign for the freedom they had so long been denied. A nationalist movement known as the Chechen All-National Congress rose to prominence, led by a mercurial and charismatic former air-force general, Dzhokhar Dudayev (1944–96). Ironically it was a last-ditch effort by hard-liners to preserve the USSR, the three-day ‘August Coup’ in 1991, which finally shattered the Union and gave Dudayev his chance. He used the opportunity to overthrow the existing Soviet administration in Grozny, declare independence and call for elections in October, which he duly won. This was largely overlooked in those final tumultuous months of the USSR, but when Gorbachev dissolved the Soviet state at the end of the year, Chechnya became newly independent Russia’s problem. While the Chechens had been a thorn in Gorbachev’s side, Russian leader Boris Yeltsin had tolerated them. Once Dudayev began advocating secession from his new Russian Federation, Yeltsin had no more time for him. Yeltsin declared the election null and void and issued a warrant for Dudayev’s arrest, sending a battalion of MVD VV (Ministry of Internal Affairs Interior Troops) in a failed bid to enforce it. This proved the true catalyst of Chechen nationhood. The more Moscow inveighed against Dudayev, the more he became canonized as a hero of national independence. While still legally part of Russia, Chechnya became effectively independent. In December 1992, Ingushetia formally broke away to become a republic on its own within the Russian Federation, while Chechnya increasingly challenged Moscow. Dudayev believed, it appears, that this time the Russians would be unable or unwilling to spend blood and treasure bringing the Chechens back into the fold. He was wrong.