Warring sides

Soldiers versus fighters

Russian troops, when confronted with heavy armed and determined Chechens, have simply stood aside – something I saw with my own eyes.

– Journalist Anatol Lieven, Chechnya: tombstone of Russian power (1998)

Just as in conflicts past, this would be an asymmetric conflict from the first – although the Russians would eventually learn a hard-fought lesson, that the best way to fight a Chechen is with another Chechen. In the main, though, the two Russo-Chechen wars saw a conventional military machine and a nimble local insurgent movement each seeking to force the other to fight on their terms.

The Tunguska self-propelled gun-missile air-defence system was built to protect Russian forces from advanced threats from the skies, but it proved an invaluable field-expedient weapon to sweep snipers, spotters and RPG teams from roof-tops and upper floors with its twin 35mm autocannon. This is the 2S6M1 Tunguska M1 variant. (© Vitaly Kuzmin)

Russian and federal forces

Moscow certainly had all the advantages on paper. At the time of their first invasion, at the end of 1994, the Russian Armed Forces officially numbered over 2 million, on paper. However, this was a war machine whose gears were rusty, whose levers were broken and whose fuel was sorely lacking. It was really just an exhausted fragment of the old Soviet Armed Forces, unreformed and largely unfunded: it was receiving only 30–40 per cent of the budget it needed simply to maintain its fighting condition, let alone modernize and reform. Every unit was actually under-strength. The cohesion of units was often appallingly bad: there was no professional NCO corps to speak of – sergeants were conscripts with a few months’ extra training and junior officers performed many of the roles carried out by NCOs in Western armies – and morale was generally poor. After all, pay was low and often late (as of mid-1996, pay arrears had reached $889 million) and even basics such as food and heating in winter were never guaranteed. In a vicious circle, this contributed to a brutal and sometimes lethal culture of hazing and bullying called dedovshchina (‘grandfatherism’) which undermined the inter-personal ties within units so vital in a guerrilla war.

A Russian sniper with SVD rifle and his spotter take up positions during a patrol of a southern Chechen village during mopping-up operations in December 2000. The increased use of snipers was one of the lessons Moscow learned from the First Chechen War. (© - /epa/Corbis)

The bulk of federal forces in the Joint Group of Forces (OGV), especially in the First Chechen War, were standard motor-rifle infantry, mechanized infantry in Western parlance. They moved in trucks sometimes, but otherwise BTR-70 and BTR-80 wheeled armoured personnel carriers or BMP-2 infantry combat vehicles, and their units were leavened with T-72 or T-80 tanks. Already rather dated, these tanks were poorly suited for operations in cities and highlands, especially as the reactive armour which might have helped defeat the simple, shoulder-fired anti-tank weapons wielded by the Chechens was available but generally not fitted. Units would cycle in and out of the OGV over the course of the conflicts, but for most of the time they comprised conscripts from the units of the North Caucasus Military District (SKVO), serving two-year terms, whose training – like their equipment – was still essentially based on Soviet patterns. As such, they were geared towards fighting mechanized mass wars on the plains of Europe or China. The painfully won lessons of Afghanistan had often been deliberately forgotten or ignored by a high command that thought it would never again be fighting a similar war. Likewise, the last specialized urban-warfare unit in the Russian military had actually been disbanded in February 1994. Furthermore, units were often cobbled together from elements drawn from other parent structures, without having had time to train together and cohere. As a result, the Russian infantry was largely unprepared for the kind of scrappy yet often high-intensity fighting it would face in Chechnya, lacked effective low-level command and initiative and was often forced to improvise or fall back on raw firepower to make up for other lacks, a factor that contributed to civilian casualties and the federal military’s poor reputation with the civilian population.

All that being said, the federal forces should not be considered entirely or uniformly degraded. Some of the units deployed were of distinctly higher calibre, especially the Spetsnaz (‘Special Designation’) commandos and the VDV (Airborne Assault Forces) troops, as well as particular elements of the Russian Armed Forces and the MVD VV (Ministry of Internal Affairs Interior Troops). Indeed, once the qualitative weaknesses of the federal armed forces became clear, there was something of a scrabble to find better-trained and -motivated forces to deploy there, including Naval Infantry marines and OMON (Special Purpose Mobile Unit) police riot troops (who were at least professionals, and who were well prepared for urban operations).

Much of the equipment with which the Russians fought had serious limitations or was ill-suited to this conflict. Nevertheless, there were also elements of the Russian arsenal which certainly carried their weight. The Mi-24 ‘Hind’ helicopter gunship, while a design dating back to the late 1960s, none the less would demonstrate its value in scouring the lowlands and hillsides alike, just as it had in Afghanistan, especially in the Second Chechen War.1 By the same token the Su-25 ‘Frogfoot’ ground-attack aircraft proved a powerful weapon in blasting city blocks with rockets and bombs, even though ten were lost through the two wars to enemy fire and mechanical problems.2 However, much of the key fighting was against snipers and ambushers, and weapons able to bring overwhelming firepower rapidly to bear in these conditions were often crucial. For example, the man-portable RPO-A Shmel incendiary-rocket launcher was often called ‘pocket artillery’ for its ability to blast a target with a thermobaric explosion equivalent to a 152mm artillery round.

Beyond this, the Russians learned and improvised. When it became clear that their armoured personnel carriers were all too vulnerable to Chechen rocket-propelled grenades, they began welding cages of wire mesh around them to help defeat the enemy’s shaped charges. Likewise, the ZSU-23-4 and 5K22 Tunguska self-propelled air-defence vehicles, armed with quad 23mm and double 30mm rapid-fire cannon respectively, were pressed into service as gun trucks; they could elevate their weapons high enough to sweep a hilltop or building roof and lay down withering fire. The acute lack of decent maps of Chechnya, a serious problem in the early days of the invasion, was partly remedied by scouring the closed-down bookshops of Grozny.

It is also important to note that there was a distinct difference between the federal forces that fought in the First Chechen War of 1994–96 and those of the Second, 1999–2009. By 1999 the military and political leadership had learnt many of the lessons of their initial humiliation. They had spent time and money preparing for the rematch and assembled forces that were far more suited to this conflict. Much more and better use was made both of special forces and MVD VV units. The latter are essentially light infantry, although some units are mechanized, with a particular internal-security and public-order role. As a result, they were more prepared for operations in Chechnya, especially those involving mass sweeps of villages hunting for rebels, arms caches and sympathizers. The MVD also disposes of a range of elite forces, from the OMON police units through to its own Spetsnaz units, many of which were rotated through Chechnya. Alongside them were deployed a larger number of other elite security forces, including the Alpha anti-terrorist commando unit of the Federal Security Service (FSB).3

The MVD VV would carry much of the fighting in both wars, even if the Russian Armed Forces took the lead in the actual invasions. Their quality varied dramatically, from undertrained and ill-prepared local security elements to the relatively elite troops of the Independent Special Purpose Division. (© Vitaly Kuzmin)

More generally, the Second Chechen War also saw a greater use of new weapons and equipment, from body armour and night-vision systems for the soldiers to reconnaissance drones in the skies. However, the main changes were in the preparations made beforehand, a willingness to adapt to Chechen tactics – such as by creating special ‘storm detachments’ for urban warfare – and a more sophisticated overall strategy. If in the First Chechen War the implicit assumption was that Chechens were all threats to be neutralized, in the Second the Russians adopted a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, they were ruthless in their control of the Chechen population, but on the other, they eagerly recruited Chechens, including rebel defectors, to a range of security units, realizing that such fighters were often best suited to taking the war to the rebels. The Russians, after all, had the firepower, but their Chechen allies could often best guide them how and where to apply it.

Grozny, 1 March 1995: a group of Chechen fighters still holding out against the Russians in the outskirts of the city, brandishing a motley collection of weapons including PK general-purpose machine guns, AKM-47 assault rifles and an RKG-3M antitank grenade. (© Christopher Morris/VII/Corbis)

Although the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI) formally had its own security structures, they did not last long once the war began and the fight was soon in the hands of more irregular units, even if at times they were able to display unusually high levels of discipline and co-ordination. When the Russians invaded in 1994, they faced a Chechen Army, a National Guard and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Russian bombers had essentially destroyed the Chechen air force on the ground on the eve of invasion). These forces were at once more and less formidable than they seemed: less formidable in that many of the units were far smaller than their titles suggested. The Army, for example, fielded a ‘motor rifle brigade’ that was actually little more than a company, with some 200 soldiers; the Shali Tank Regiment (some 200 men, with 15 combat-capable tanks, largely T-72s); the ‘Commando Brigade’ (a light motorized force of 300 men); and an artillery regiment (200 men, with around 30 light and medium artillery pieces). To these 900 or so troops could be added the ‘Ministry of Internal Affairs Regiment,’ another light motorized force of 200 men. However, about twothirds of the ChRI’s field strength of 3,000 had been drawn from the so-called National Guard. This was a random collection of units, ranging from the gunmen of certain clans through to the personal retinues of particularly charismatic leaders as well as Dudayev’s own guard. These had such picturesque names as the ‘Abkhaz Battalion’ and the ‘Muslim Hunter Regiment’, few of which truly reflected their real size or role.

However, this ramshackle assemblage of forces did have several significant examples. They knew the country well and while they were no longer quite the hardy outdoorsmen of the 19th century, having adapted to the age of the car, central heating and college, their traditions did grant them a certain esprit de corps. They also knew their enemy, most having served their time in the Soviet or Russian military. Indeed, given the martial reputation and enthusiasm of the Chechens, a disproportionate number had served in the VDV or Spetsnaz, experience which would serve them well in the coming wars. In age, they spanned the full range from adolescents to pensioners, although the typical fighter was in his mid- to late twenties.

While some units still retained a more formal structure modelled on the Russian forces, in the main they fought in units of around 25 men broken into three or four squads. They were largely armed only with light personal and support weapons, especially AK-74 rifles, RPG-7 anti-tank grenade launchers, disposable RPG-18 rocket launchers, SVD sniper rifles, grenades and machine guns. However, thanks to that martial tradition, as well as the preceding years of rampant criminality which had seen guns smuggled into the country and state arsenals opened, they had plenty of those, not least the ammunition and spares the lack of which is often the guerrilla’s bane.

Besides which, their numbers would quickly be swollen by volunteers from across the country, from the Chechen diaspora elsewhere in Russia and, eventually and ultimately counter-productively, from Islamist militants from the Middle East. This would be an ‘army’ of warlords and their followings, even if during the First Chechen War and the early years of the Second there was still some sense of a command structure, largely anchored around the person of Aslan Maskhadov (1951–2005), the chief of staff of the Chechen military and later their elected president. Even so, this was a force whose size fluctuated by the season and the day, not least as individuals might take up arms for a particular operation and then return to their civilian activities until the next.

Grozny, 29 January 1997: a characteristically miscellaneous group of Chechen rebel fighters demonstrate their enthusiastic support for Aslan Maskhadov, the rebel general who assumed office as their elected president the following month. They are waving an equally characteristic mix of older and newer weapons: AKS-47 and AK-74 rifles and an RPK light machine gun with box magazine. (Vladimir Mashatin/EPA)

Above all, they were characterized by a fierce determination and excellent tactics. These were often unconventional, but rooted in an understanding of how their enemies operated. Knowing the Russian propensity for the artillery barrage, for example, in urban warfare they ‘hugged’ Russian units, keeping within a city block or so of them so that the Chechen forces were safe from bombardments. Likewise, the Chechens were well aware that the guns of Russian tanks could not depress enough to engage basement positions, in which they built makeshift bunkers from which to attack Russian advances. Finally, they drew on their strengths, from sticking to using Nokhchy for their communications, knowing the Russians could intercept their radio traffic but not generally understand it, to drawing the federal forces into traps and ambushes in the cities and mountains that they knew so much better.

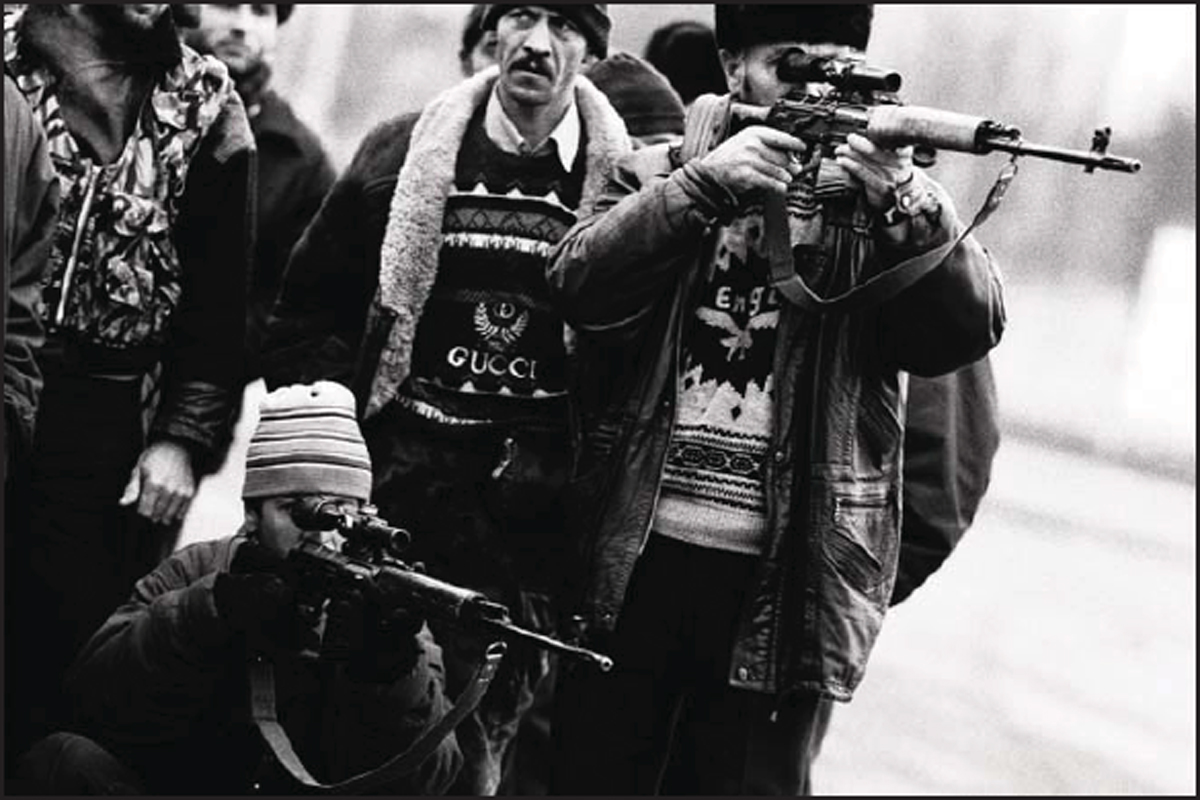

Rebel fighters aiming SVD Dragunov rifles during the battle for Grozny, January 1995. SVDs are at best moderately accurate weapons, but a tradition of hunting and weapon-handling from a young age meant many Chechens could get the best out of them. (© Christopher Morris/VII/Corbis)

1 See New Vanguard 171, Mil Mi-24 Hind Gunship (2010).

2 See Air Vanguard 9, Sukhoi Su-25 Frogfoot (2013).

3 See Elite 197, Russian Security and Paramilitary Forces since 1991 (2013).