Outbreak

Flashpoint: 1994

Intervention by force is impermissible and must not be done. Were we to apply pressure by force against Chechnya, this would rouse the whole Caucasus, there would be such a commotion, there would be such blood that nobody would ever forgive us.

– President Yeltsin, 10 August 1994

As the USSR began to break apart under General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, an opportunist Communist Party boss called Boris Yeltsin (1931–2007), angered by the political machinations that had seen him sacked from his position as First Secretary of Moscow, turned to anti-communist rhetoric to win himself a new political constituency. He won election after election, in July 1991 becoming president of the Russian republic within the USSR. The failed August Coup later that year by hard-line Communists opposed even to Gorbachev’s more moderate reforms allowed Yeltsin to become the standard-bearer of change. When Yeltsin refused to sign his proposed new Union Treaty, which would have introduced dramatic changes but preserved the USSR, Gorbachev was forced to bow to the inevitable. On the last day of 1991, he signed the USSR out of existence, creating 15 new states, including the Russian Federation.

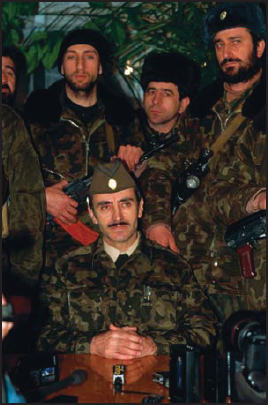

Russian President Boris Yeltsin confers with his one-time Defence Minister, General Pavel Grachev, amid other Russian officers. While Grachev had been a successful VDV commander in Afghanistan, he was appointed minister in May 1992 because of his loyalty rather than his ability, and his advice would lead Yeltsin to underestimate the challenge of subduing Chechnya. (© Robert Wallis/Corbis)

However, this was a new nation created by default and from the first would encounter challenges between the centralizing impulses of Moscow and the national aspirations of some of the members of this federation. Originally, Yeltsin had suggested that constituent members of the Russian Federation would be free to chart their own destinies, but as ever this proved a promise easier to make while seeking office than to keep once in power. The head of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Doku Zavgayev, had failed to repudiate the August Coup and had been hounded out of office. In October 1991, a referendum was held to confirm Dzhokhar Dudayev, then the head of the informal opposition All-National Congress of the Chechen People, as president. He immediately declared the republic independent – something the minority Ingushetians questioned and Yeltsin flatly refused to accept. Moscow declared a state of emergency and dispatched an MVD VV regiment to Grozny. However, when the lightly armed security troops touched down at Khankala airbase outside the city, they were surrounded by a far greater number of Dudayev’s forces. Gorbachev refused to let the Soviet Armed Forces get involved and Yeltsin shied away at the time from escalating, so after some tense negotiations the MVD VV troops were allowed to leave by bus. Moscow had challenged Grozny and Grozny had won, the first round at least, leaving Dudayev a national hero and Chechnya believing itself finally free.

Dzhokhar Dudayev

Born in 1944, Dzhokhar Musayevich Dudayev had experienced Stalin’s resettlement at first hand, spending his first 13 years in internal exile in Kazakhstan. Even so, he joined the Soviet Air Force, becoming a bomber pilot in the Long-Range Aviation service. He was decorated for his service during the Soviet–Afghan War in 1986–87, and in 1987 became a major-general, the first Chechen to reach general rank in the air force. He was appointed commander of the 326th Heavy Bomber Division in Tartu, Estonia. This was a nuclear strike force, suggesting that the authorities considered his loyalty beyond question. Nevertheless, while there he seems to have been affected by the growing nationalist mood of the Estonian people and he demonstrated considerable sympathy towards them.

In 1990, when his unit was withdrawn from Estonia, he retired from the military and returned to Chechnya. There he threw himself into nationalist politics and was elected chair of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People. He demonstrated a willingness to take full advantage of circumstances, and when local Communist Party boss Zavgayev’s position looked shaky after the 1991 August Coup, Dudayev dispatched militants to seize the local parliament and TV station and, in effect, stage a coup of their own, retrospectively legalized in a referendum.

In power, though, Dudayev proved much less effective, largely delegating matters of state to cronies more interested in enriching themselves, while he spent his time practising karate (he was a black belt). When the Chechen parliament tried to stage a vote of no confidence in his leadership in 1993, he had it dissolved. When the Russians invaded in 1995, he continued to lead the government in principle, although operational command soon devolved to more capable field officers. He was killed outside the village of Gekhi Chu on 21 April 1996, while on a satellite phone to a liberal Russian parliamentarian. Although conspiracy theories abound as to booby traps, it seems most likely that he was killed by two missiles fired from a Su-25 attack jet after a Russian electronic intelligence aircraft detected the signal.

Dzhokar Dudayev gives a statement to the media, 11 January 1995. (© Peter Turnley/Corbis)

In March 1992, a new Federation Treaty was signed as the foundational document of the Russian state and Chechnya refused to take part. As a result in June Ingushetia formally split from Chechnya, petitioning successfully to be incorporated into the Russian Federation as the Republic of Ingushetia. Meanwhile, the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI) affirmed its own statehood, with a flag and national anthem – even if no international recognition.

This was not a tenable state of affairs. On the one hand, Yeltsin was increasingly worried about the long-term implications of allowing Chechnya’s withdrawal from the federation as a precedent. Indeed, Dudayev was eager to create a federation of the Caucasian gorsky peoples in the mould of Imam Shamil, although his Confederation of Caucasian Mountain Peoples never amounted to much. The much larger and economically important Republic of Tatarstan had already negotiated for itself special membership terms and there were even fears that territories east of the Urals might seek to break free some day.

Not that the ChRI was stable in any sense. While three of Chechnya’s 18 constituent regions were threatening secession, Dudayev began to talk of the forced re-incorporation of Ingushetia. Conversely, the Terek Cossack Host laid claim to parts of Chechnya. There appeared ample scope for unrest, local insurrection, even civil war, given that under Dudayev, Chechnya was becoming a virtual bandit kingdom. Organized crime flourished, not least within the new ChRI state apparatus. The Chechen State Bank, for example, was used to defraud its Russian counterpart of up to $700 million using fake proof of fund documents. Russian oil pipelines which ran through Chechnya were not only at risk of destruction but also being tapped illegally and even though Grozny was still a hub for oil refining, in the first two years of independence not a single new school or hospital was built and industrial production fell – largely as a result of under-investment – by 60 per cent.

Chechnya was becoming a genuine threat. At least as important, Yeltsin needed to prove that no one could challenge Moscow with impunity. There was also a political dimension: increasingly unpopular at home as the economy collapsed, he wanted an enemy and a success to distract the public. A conflict became increasingly inevitable. In August Yeltsin was still describing a military intervention by federal forces as ‘impermissible’ and ‘absolutely impossible’; it was not that he was ruling out action, just that he hoped to rely instead on Chechens opposed to Dudayev, who had formed the Provisional Chechen Council. In October and November 1994, Provisional Chechen Council forces, armed and encouraged by Moscow (and supported by Russian airpower) launched abortive incursions into Chechnya. This proved a disaster; they were easily defeated by Dudayev loyalists, who captured Russian soldiers among them and paraded them on TV. To an extent, this reflected the unexpected level of support Dudayev’s regime still had, but it was also a product of poor planning on the Russian side. The Provisional Chechen Council was essentially a tool of Russia’s domestic security agency, then still called the Federal Counter-Intelligence Service (FSK), but later the Federal Security Service (FSB). It was the FSK that was pushing for intervention and the troops involved, while drawn from Armed Forces units, had actually been hired by the FSK without the explicit clearance of the Armed Forces High Command. According to the testimony of captured soldiers, FSK recruiters had offered them the equivalent of a year’s pay to prepare tanks for the operation, and the same again to crew them in support of the Chechen irregulars. They were also told that Dudayev had already fled, his forces were demoralized and the people of Grozny were ready to welcome them with flowers and cheers. Instead, of the 78 Russian soldiers accompanying the irregulars into Chechnya in November, only 26 made it home, with the rest killed or captured. When Major-General Boris Polyakov, commander of the elite 4th Guards ‘Kantemir’ Tank Division, heard that some of his soldiers had been hired by the FSK without his knowledge, he angrily resigned his position.

Although not as widely or always as competently used as during Afghanistan – especially as the rebels had very little anti-aircraft capability – the Mi-24 helicopter gunship would remain a mainstay of Russian fire-support operations in Chechnya and would also engage in ‘free hunts’ across rebel-held areas, engaging at will with guns and rocket pods. (Pyotr Novikov/EPA)

Russia’s Chechen ‘Bay of Pigs’ put Yeltsin in a position in which he could either escalate or back down. Characteristically, he escalated, encouraged by his compliant defence minister, General Pavel Grachev, who airily reassured him that ‘I would solve the whole problem with an airborne regiment in two hours.’ On 28 November, a secret session of select members of the Security Council met to consider next steps and decided to invade. This was then put to the full Security Council the next day, but with Yeltsin and his closest allies set on intervention, there was no real scope for debate, even though Yevgeny Primakov, head of the Foreign Intelligence Service and a veteran Middle East specialist, counselled caution. As a result, on 30 November, Yeltsin signed Presidential Decree No. 2137, ‘On steps to re-establish constitutional law and order in the territory of the Chechen Republic.’

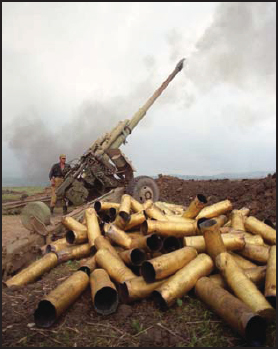

The Russians have traditionally depended heavily upon artillery, the ‘Red God of War’. The conflict in Chechnya would be no exception, with long-range firepower often standing in for weaknesses in close-in capability. Here, Russians pound rebel positions near the highland village of Bamut on 24 May 1996. (Yuri Kochetkov/EPA)

Even ahead of that vote, on 28 November the Russian air force bombed Chechnya’s small air force on the ground and closed its two airfields by cratering the runways. Meanwhile, an invasion force was mustered in three contingents. The first, based in Mozdok, North Ossetia and commanded by Lieutenant-General Vladimir Chilindin, numbered 6,500 men. It was based on elements of the 131st Independent Motor Rifle Brigade, nine MVD VV battalions and the 22nd Independent Spetsnaz Brigade. The second, mustering at Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, was under Lieutenant-General Chindarov – the deputy head of the Airborne Forces – and comprised 4,000 troops from the 19th Motor Rifle Division and the 76th Airborne Division, as well as five MVD VV battalions. The third, under Lieutenant-General Lev Rokhlin, assembled at Kizlyar, Dagestan, with 4,000 troops drawn from the 20th Motor Rifle Division and six MVD VV battalions. Together with other forces, including the air assets committed to the operation, the total force was around 23,700 men, including 80 tanks, under the overall command of Colonel-General Alexei Mityukhin, commander of the North Caucasus Military District (SKVO).

On 11 December, as Yeltsin disappeared from public view reportedly for a minor operation – to avoid embarrassing questions – federal forces moved into Chechnya along three axes that then split into six. Already that represented a deviation from the original plan, which had envisaged starting on 7 December, but the forces had not yet been ready. Within three days they were meant to be ready to storm Grozny, but in fact local resistance, bad weather and a rash of mechanical difficulties meant they were not emplaced around the city until 26 December. Nevertheless, they had reached the Chechen capital and the real war was about to begin. When the Russians moved in on 31 December, they were met not by cheering crowds throwing flowers and kisses at their liberators, but a population mobilized for war and charged by a 200-year history of struggle.