The fighting

Two wars

A few days are enough to ignite a military conflict; to purge and achieve order [takes] years.

– Commentary in newspaper Izvestiya, 1995

Karl Marx had it that history repeated itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. In this case, while it is hard to deny that the First Chechen War was a tragedy, the Second Chechen War was far from a farce. Instead, it proved that despite all its serious limitations, from a dearth of well-trained troops to a lack of an urban warfare and counter-insurgency doctrine, under Putin the Russian state was nevertheless able and willing to spend resources and political capital to crush this, the most serious Chechen attempt to date to throw off foreign domination. In many ways, then, the two wars stand as stark symbols of the respective unfocused amateurism of the Yeltsin regime and the ruthless determination evident under Putin.

A Chechen fighter fires on federal positions with a PKM general-purpose machine gun. This was a highly prized weapon amongst the rebels, not least as its 7.62mm ammunition was readily available, looted from Soviet-era stocks inside the country. (© Christopher Morris/VII/Corbis)

The first battle for Grozny

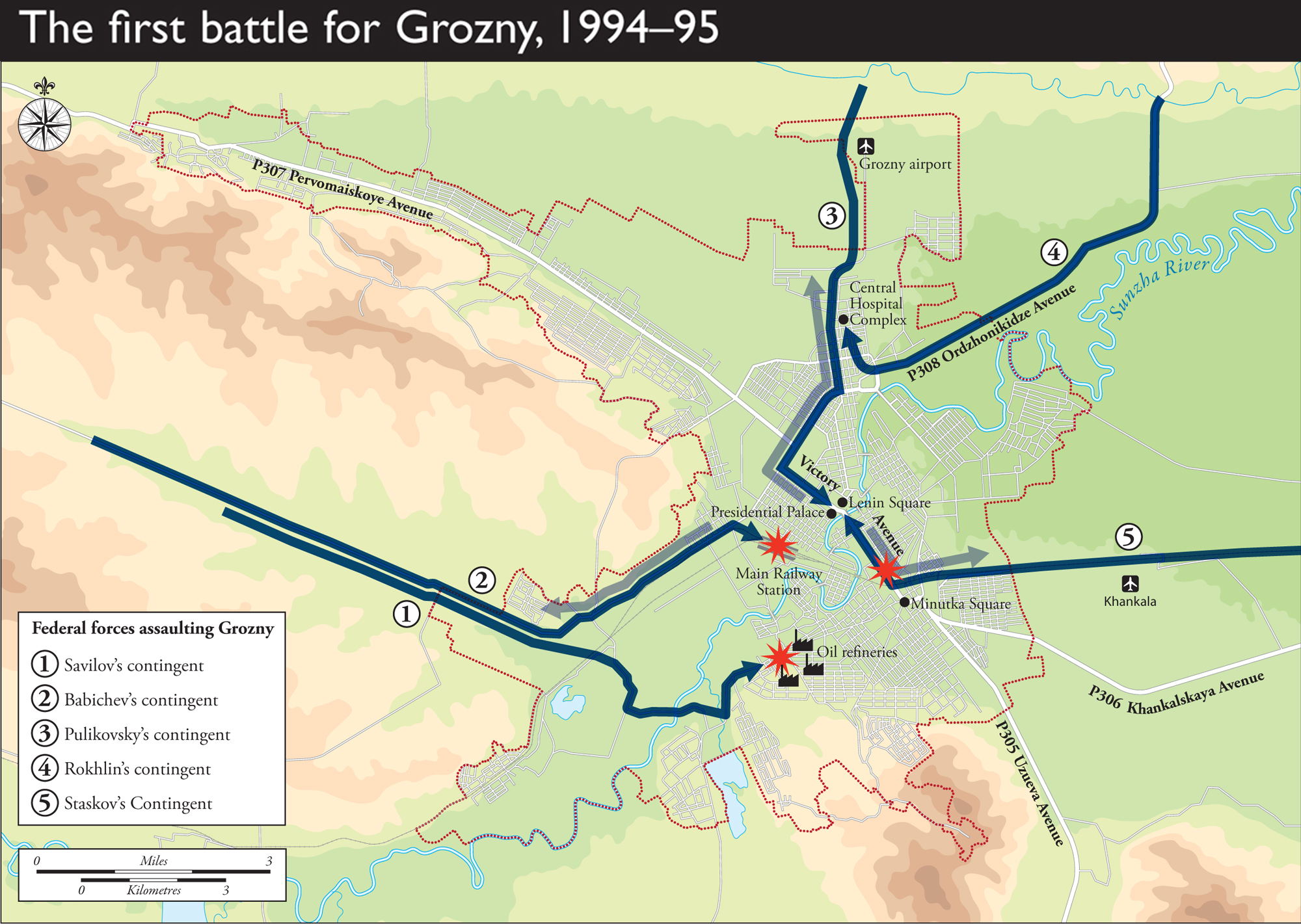

The Russians’ assumption was that seizing Grozny would mean the end of the war. This planning decision showed not only that they had forgotten the experiences of past wars with the Chechens, or even the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979; it also drove them to try to push towards and into the city more quickly than they should. Federal forces were gathered in a special Joint Grouping of Forces (OGV) that was predominantly made up of units from the Armed Forces and the MVD, but also included FSB units (including some Border Troops, subordinated to the FSB), elements of the separate Railway Troops and detachments from the Ministry of Emergency Situations (MChS). Co-ordination between these various forces was inevitably going to be problematic, especially as the preparations had been hurried, and this was another factor behind the relatively simple ‘drive to Grozny’.

The plan was that these taskforces would push directly to Grozny and surround it. While MVD troops locked down the countryside, Armed Forces units would assault the city from north and south, seizing key locations such as the Presidential Palace, main railway station and police headquarters before the Chechens had had the chance to prepare proper defences, and then mop up any remnants of Chechen resistance as remained. However, the plan ran into problems from the first. The three taskforces – which had had to advance along multiple routes because of the geography and the width and quality of roads – all failed to keep to schedule, so Grozny was never effectively blockaded, especially to the south, allowing its defenders to be reinforced with volunteers and raising their numbers to perhaps 9,000 by the height of the battle. With the Russian first wave only numbering some 6,000 men, given the advantages for the defence in urban warfare, this was a serious development for the federal forces. They were to have to throw substantially more into the fray before they eventually took the city and levelled much of it in the process.

OGV commanders in the First Chechen War

| 1994–95 | Colonel-General Alexei Mityukhin (Armed Forces) |

| 1995 | General Anatoly Kulikov (MVD) |

| 1995 | Lieutenant-General Anatoly Shkirko (MVD) |

| 1996 | Lieutenant-General Vyacheslav Tikhomirov (Armed Forces) |

| 1996 | Lieutenant-General Vladimir Shamanov (Armed Forces) |

The Chechens had also had longer than anticipated to prepare. Under military chief of staff Aslan Maskhadov, the Chechens established three concentric defensive rings and had turned much of the centre of the city into a nest of ad hoc fortifications. Buildings were sandbagged and reinforced to provide firing positions, while – knowing the Russian propensity for the direct attack – the few tanks and artillery pieces the Chechens had were emplaced to command those roads wide enough for an armoured assault, notably Ordzhonikidze Avenue, Victory Avenue and Pervomayskoye Avenue. Further out, there were defensive positions at choke-points such as the bridges across the Sunzha River, as well as around Minutka Square south of the centre.

The Russian plan called for assault elements of the 81st and 255th Motor Rifle regiments to attack from the north under Lieutenant-General Konstantin Pulikovsky, supported by the 131st Independent Motor Rifle Brigade and 8th Motor Rifle Regiment. Meanwhile, elements from the 19th Motor Rifle Division under Major-General Ivan Babichev would move in from the west, along the railway tracks to seize the central station and then advance on the Presidential Palace from the south. From the east, Major-General Nikolai Staskov would lead assault units from the 129th Motor Rifle Regiment and a battalion of the 98th Airborne Division again along the railway line to Lenin Square and thence capture the bridges across the Sunzha River. From the north-east, elements of the 255th and 33rd Motor Rifle regiments and 74th Independent Motor Rifle Brigade under Lieutenant-General Rokhlin would take the central hospital complex, from where they could support other advances. Finally, units from the 76th and 106th Airborne divisions would be deployed to prevent the rebels from firing the Lenin and Sheripov oil-processing factories or chemical works, as well as blocking efforts by the rebels to attack the assault units from behind.

An Armed Forces BTR-80 armoured personnel carrier in Grozny, 1 August 1995. It was common for troops to ride or rather than inside their vehicles in high-risk environments since, not least because – despite improvements from the earlier BTR-60/70 models – it is still difficult to disembark from a BTR if it is hit by a mine or rocket. (© Jon Spaull/CORBIS)

The attack began on 31 December after a preparatory air and artillery bombardment and soon ran into trouble as Chechen resistance proved fiercer than anticipated. The western advance soon bogged down in fierce street-to-street fighting. The eastern group was forced to detour and found itself in a kill-zone of minefields and strong-points. The northern group managed to push as far as the Presidential Palace, but there likewise found itself unable to break dogged resistance, and dangerously exposed by the failure of the other groups. Furthermore, a lack of training, the use of forces cobbled together from elements from different units and poor morale quickly proved problematic. Advances became snarled in traffic jams of armoured vehicles, friendly-fire incidents proliferated and units coming under fire showed a propensity to halt and take cover, rather than press on as intended.

Perhaps the most striking reversal was the fate of the 1st Battalion of the 131st Independent Motor Rifle Brigade, which by the afternoon of the first day had reached the main railway station and had assembled at the square outside it. There they were ambushed by well-positioned Chechen forces in buildings all around the square, which soon became an inferno of small-arms and RPG fire. When survivors fled into the station building, it was set on fire. When other elements of the 131st tried to support their comrades, they were ambushed and blocked. The battalion lost more than half its men and almost all its vehicles; in effect, it had ceased to exist.

By 3 January, the Russian attack had effectively been beaten back. Their only forces still in the city in good order were Rokhlin’s group, which had not been expected to drive to the Presidential Palace and had thus avoided the worst of the fighting and had been able to dig in. Even so, this could only be a temporary respite. The Russians redoubled their air and artillery campaign against the city, and adopted a much more cautious campaign, slowly grinding their way through the city. On 19 January, they seized the Presidential Palace – or what was left of it after it was hit by bunker-busting bombs – and although fighting would continue in the south of the city for weeks to come, Grozny had essentially fallen. But it was a ruin, strewn with the bodies of thousands of its citizens – estimates range up to 35,000 – in a bloodbath that the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) would describe as an ‘unimaginable catastrophe’. This would not, however, be the last battle for this ill-fated city.

Interior Minister Anatoly Kulikov (left) and Defence Minister Igor Rodionov (right) at a press conference in October 1996 to launch a book of the names of fallen Russian soldiers in the First Chechen War. Armed Forces General Rodionov, a former commander of forces in Afghanistan, was deeply sceptical of the First Chechen War and Yeltsin’s reform priorities and would be sacked in May 1997, but the hawkish Kulikov was a key mover behind the conflict. (Vladimir Mashatin/EPA)

Yeltsin’s messy war

On 6 January 1995, the Security Council had announced that military actions in Chechnya would soon be coming to an end; it was take almost another two weeks before they even controlled the ruins of the Presidential Palace. Contrary to Russian expectations, though, the fall of Grozny did not end the war. Instead, what would follow would devolve into a messy series of local brawls, sieges, raids and feints. The towns of Shali, Gudermes and Argun held out for months and federal forces seemed to show little enthusiasm to engage in further urban warfare.

In what became a traditional way of expressing disapproval of the progress being made, Yeltsin decided to change commanders and on 26 January, Deputy Interior Minister General Anatoly Kulikov, head of the MVD VV, was given overall charge of the operation. At the same time, efforts were being made to negotiate a settlement and on 20 February, Maskhadov met his Russian counterpart, Chief of the General Staff General Anatoly Kvashnin. But there was no real scope for agreement: the Russians would accept nothing short of complete capitulation. From the Russians’ point of view, at least the pause gave them a chance to regroup and reinforce. More and better troops were rushed to Chechnya, from wherever they could be found: part of the MVD VV’s 1st Independent Special Designation Division – the elite ‘Dzerzhinsky Division’ from Moscow – as well as the Vityaz anti-terrorist commando unit, Naval Infantry from the Northern, Pacific and Baltic Fleets (though the commander of one Pacific Fleet battalion refused his orders) and the Armed Forces’ elite 506th Motor Rifle Regiment. In total, the OGV was brought to 55,000 personnel from the MVD and military. The FSK set up a Chechnya directorate. In short, having realized that this was hardly going to be the quick or neat operation it had anticipated, Moscow hurriedly looked to raise its game.

Ceasefire talks broke down on 4 March; the next day, federal forces began their assault on Gudermes, although this would prove a lengthy, on-and-off process. Argun fell more easily, on 23 March, and by the end of April, most main centres were loosely in federal hands, even if attacks continued regularly. Having originally suggested that Grozny was returning to normal, in May the Russians were forced to introduce a curfew and admitted that hundreds of rebel fighters remained within the city. Colonel-General Mikhail Yegorov, the temporary acting field commander of the OGV, spoke of 20 per cent of the country still being in rebel hands, in the southern highlands around Shatoy and Vedeno – they themselves claimed almost twice that.

Nevertheless, the Russian offensive ground on, with Kulikov asserting that no more than 3,000 fighters still supported Dudayev, a figure that remained suspiciously constant throughout the war. On 13 June, the Russians claimed – and the Chechens admitted – that they had taken Shatoy and the nearby town of Nozhay-Yurt. Moscow began to believe that the end of the war was close. However, the Russians’ notion that this was a conflict whose progress could be charted by map was flawed. Although the rebels only controlled a small portion of southern Chechnya, the Russians had neither the numerical nor the moral strength to be said to control the rest. By day, the Armed Forces and MVD patrolled the cities while Mi-24 helicopter gunships tracked along roads and pipelines. There were sporadic bomb and sniper attacks in the cities and ambushes outside, but in the main the Russians did not try to penetrate too deeply into the highlands and villages and the Chechens knew that a direct confrontation with the federal forces would bring a devastating response. By night, though, the Russians largely withdrew to their bases, mounting only occasional and heavy patrols in main cities, abandoning the country to the rebels, who used these times to regroup and relocate. This allowed the rebels to be able to mount attacks throughout the country still. Besides, what was looming was the start of a whole new type of war, one for which the Russians were distinctly unprepared.

Even as the Russians were making their grandiose assertions, a convoy of trucks was travelling up the P263 highway, into Stavropol Region. Some 195 Chechen fighters under rebel commander Shamil Basayev bluffed and bribed their way past successive police checkpoints, pretending to be carrying the coffins of dead soldiers home. Basayev had hoped to get further into Russia, but on 14 June, they reached a roadblock just north of the southern Russian city of Budyonnovsk 70 miles (110km) north of the Chechen border. Basayev had spent $9,000 in bribes and had run out of money, so instead his party turned round and drove back into Budyonnovsk. They seized the mayor’s office and police station and when security forces converged on the town, withdrew to the local hospital. There, they took some 1,800 hostages, mostly civilians and including some 150 children.

Budyonnovsk, 17 June 1995: two Russian soldiers run across the street near the rebel-held hospital during a key terrorist attack in the First Chechen War which at least temporarily forced the Russians to a ceasefire and consolidated Shamil Basayev’s reputation as a daring but ruthless leader. (Alexey Dityakin/EPA)

Basayev demanded that Moscow end its operations in Chechnya and open direct negotiations with the ChRI government. He threatened to kill the hostages if the Russians moved against him, tried to prevent his access to the media, or refused to accept his terms. Several times, government forces tried to storm the building but were driven back. Eventually Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin personally negotiated a resolution that in effect granted the Chechens their demands. On 19 June, Basayev and his remaining fighters, accompanied by over 100 volunteer hostages, including journalists and parliamentarians, were allowed back into Chechnya. Much of Budyonnovsk was in ruins, 147 people were dead (many from Russian fire), but perhaps most comprehensively shattered was Moscow’s confidence and its claims that the war in Chechnya was going easily to be won. Chernomyrdin was no dove, but seizing the moment while Yeltsin was away at a conference in Canada, he was shrewd enough to know when to cut a deal.

Basayev’s men had suffered just 12 casualties, yet their act of terrorism had not only humbled their enemies – FSK director Sergei Stepashin and Interior Minister Viktor Yerin, both hawks, were forced to resign because of the mismanagement of the crisis – it had changed the course of the conflict. It did not end the war, but it demonstrated convincingly that the Russians were asymmetrically vulnerable to unexpected threats. Nevertheless, although negotiations and ceasefires came and went over following months, something of a bloody stalemate seemed to be emerging. The Chechens could not dislodge the federal forces, nor, as in history, meet them in open battle. However, the Russians were unable to bring their forces properly to bear on the rebels and end the war. A case in point was the battle of Gudermes in December 1995. On 14 December, the very day Chechens were meant to be voting for their new – Moscow-approved – republican president, some 600 rebels under Salman Raduyev attacked the country’s second largest city. They managed to take large tracts of central Gudermes, considered one of the most secure federal strongholds in Chechnya, although they were not able to storm its military headquarters. For two weeks, federal forces launched repeated assaults, interspersed with artillery barrages, but while Raduyev’s men could not expand their grip on the city, nor were the Russians able to break them. Eventually, a local ceasefire was agreed and Raduyev and his forces were allowed safe passage out of the city. Gudermes returned to federal hands, but at the price of allowing the rebels out to fight another day.

Pervomayskoye, 11 January 1996: when Chechen rebels launched a cross-border raid into Dagestan in 1996, they took hostages, like these civilians, as human shields in order to be able to withdraw safely. Such incidents help explain why Dagestanis would actively take up arms to repel the ‘International Islamic Peacekeeping Brigade’ when it invaded in 1999. (Oleg Nikishin/EPA)

That they did. On 9 January 1996, Raduyev led some 200 fighters into neighbouring Dagestan to attack the airbase at Kizlyar. They only destroyed two helicopters there – most were elsewhere or on operations – but when federal forces responded, seemingly more quickly than he had anticipated, Raduyev took a leaf out of Basayev’s playbook. His men retreated to the nearby town, took over 1,000 hostages and holed up in the city hospital and an adjacent building. A deal was struck allowing them to return to Chechnya in return for the hostages. Most were let go, with some 150 kept as human shields. However, the Russians were not willing to let Raduyev strike a third time. Just short of the border, the Chechen convoy came under fire from a helicopter and the guerrillas seized the nearby village of Pervomayskoye, taking more hostages and digging in.

There followed three days of sporadic assaults by Russian special forces, which led to heavy casualties on their side but no progress. They resorted to bombarding the village, claiming that the hostages had already been killed, while commanders competed to put the blame on others and some units seemed on the verge of mutiny. On the eighth night, though, most of the surviving Chechens managed to break through the Russian lines and flee, assisted by a diversionary attack launched by other rebel forces which had come to support them. Raduyev was among them, and would continue to elude the Russians until his capture in 2000; he died in the Russian Bely Lebed (‘White Swan’) maximum-security prison camp in 2002.

The Kizlyar/Pervomayskoye operation encapsulated the dynamics on both sides. The Chechens retained the initiative, and could win when they struck unexpectedly. They also still had forces with the morale, weapons and will to fight. On the other hand, their ‘army’ was shattering into various autonomous forces under charismatic warlords who often had their own agendas. Dudayev, after all, would contradict himself as to whether he had or had not ordered the Kizlyar attack. Raduyev, though, was one of a new generation who had little time for negotiation or moderation; whereas many of his colleagues would drift into Islamic extremism, he simply seems to have lived for the fight, whatever the costs. He had no qualms about extending the war beyond Chechnya’s borders, nor over merging war and terrorism. Meanwhile, the Russians were still slow to respond. They were also deeply divided over tactics and aims and also between institutions and officers. Many within the military, especially veterans of Afghanistan, believed that they should withdraw. Others felt that Yermolov’s policies of ethnic cleansing were needed. Meanwhile, with no clear sense of direction and no strong political pressure encouraging them to consider Chechen hearts and mind, they too often relied on indiscriminate firepower to solve any problem. In the process, while rebels were dying, others were joining up. In part this was because actions such as Budyonnovsk, Gudermes and Kizlyar were considered victories by some, but it was also in part because often-brutal Russian tactics helped galvanize resistance. In a country where avenging fallen family members and slights to one kin is still a strong part of national culture, the Russians were virtually Dudayev’s recruiting sergeants.

Makhachkala, 15 November 2001: Chechen warlord Salman Raduyev, unrepentant, at his trial. In December 2002 he died in the Russian ‘White Swan’ prison camp, for reasons still unclear. (Novoye Delo/EPA)

Dudayev himself, though, was hardly much of an asset to the rebel cause. He issued stirring pronouncements from time to time, but was neither a battlefield tactician, nor a negotiator able to use the sporadic and often half-hearted negotiations with the Russians to reach any kind of a deal. The ‘peace plan’ he proposed to Yeltsin, for example, demanded that he arrest the current and former commanders of the OGV, sack his prime minister and key security ministers and purge his parliament! Arguably Dudayev’s greatest and last gift to the Chechen cause took place on 21 April 1996, when he put a satellite phone call through to a liberal parliamentarian in Moscow and was killed by Russian homing missiles for his pains. His death meant that formal power devolved to his vice president, Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev. However, this poet and children’s author wielded relatively little real authority among members of the rebel movement, who instead looked to Aslan Maskhadov for leadership. He, in turn, knew that the Chechens were unlikely to win a war of attrition with the vastly more numerous Russians, especially as the latter were beginning to adapt to the circumstances of this war. Already, the new forces Moscow had deployed were beginning to make their weight known on the battlefield. Instead, like all great guerrilla commanders, Maskhadov knew that his struggle was essentially political. Budyonnovsk had brought the Russians to negotiations, even if ultimately that chance had been squandered. He needed an equivalent, or even greater, ‘spectacular’ to convince Moscow to come to terms, and not an act of terror but something to demonstrate that the Chechens could also win on the battlefield. His gaze turned to Grozny.

The second battle for Grozny

On 1 January 1996, Lieutenant-General Vyacheslav Tikhomirov had been appointed head of the OGV. Tikhomirov was a career Armed Forces officer, unlike his two predecessors, Kulikov (who became interior minister after Yerin) and Lieutenant-General Shkirko (another MVD VV veteran). With his arrival, the Russian forces stepped up their efforts to win on the battlefield, but in the main all that happened was that offensives would take ground, only to lose it once the tempo slackened. With Dudayev’s death in April, Maskhadov was eager to seize the military and thus political initiative. Yandarbiyev’s representatives and Moscow’s continued arm’s length, on-again-off-again talks about talks, which led to sporadic ceasefires but no real prospect of true agreement. Indeed, Yandarbiyev could not even claim to be speaking for the whole rebel movement, as Basayev said he should be deposed for talking to the Russians.

At the same time Maskhadov, who was taking an active role in peace talks being held in Nazran in Ingushetia, was also working on a fall-back option, assembling a coalition of warlords willing to take part in a daring strike. Meanwhile, the tempo of guerrilla attacks slackened somewhat, allowing the Russians to begin to think they were winning. This also allowed Moscow to make a point of doing something it had been promising to do: bring forces home. A conscript army is inevitably subject to regular rotations of units and men, and as units were withdrawn from Chechnya, they were not matched by new elements being deployed. At the end of May, Yeltsin visited Grozny – under very tight security – and told assembled soldiers from the 205th Motor Rifle Brigade, ‘The war is over, you have won.’ Reflecting this upbeat mood, by then federal forces had been allowed to shrink from their peak of 55,000 personnel to just over 41,000: 19,000 Armed Forces and 22,000 MVD VV, OMON and other security elements. Further reductions, especially to the Armed Forces contingent, were to follow: the aim was that eventually no more than one MVD VV brigade and the 205th Motor Rifle Brigade were to be left by the end of the year.

By July, the Russians had decided to escalate their operations in the south, hoping to force the rebels into accepting their terms. As they focused their forces to seize such remaining rebel strongholds as the village of Alkhan-Yurt, they pulled forces out of Grozny, including not just MVD VV garrisons but also police officers of the pro-Moscow regime. Anticipating this, though, Maskhadov had assembled forces in a daring counter-strike on Grozny itself, timed to overshadow the inauguration of Boris Yeltsin, who had just been re-elected to the Russian presidency in a poll widely regarded as rigged.

On the morning of 6 August – the very day federal forces were launching their assault on Alkhan-Yurt – some 1,500 rebels from a number of units were quietly infiltrating Grozny in 25-man units. Although the defenders had established a network of checkpoints and guard stations, their reluctance to venture out at night, as well as their reduced numbers, meant that it was relatively easy for the rebels to move into their city. At 5.50am, they struck, attacking a wide range of strategic targets including the municipal building, Khankala airbase, Grozny airport and the headquarters of the police and the FSB, as well as closing key transport arteries. They placed mines in some garrisons and set up firing stations to command the routes along which federal forces could sally.

Aslan Maskhadov

Undoubtedly the outstanding figure of the war on either side, Maskhadov was a brilliant guerrilla commander who ultimately proved unable to master the more shadowy ways of Chechen politics. Like Dudayev, he was a product of the forced dispersal of the Chechens and was born in Kazakhstan in 1951. His family returned home in 1957 and he joined the Soviet Armed Forces, serving as an artillery officer and receiving two Orders for Service to the Homeland. He retired in 1992 with the rank of colonel after a 25-year military career. Returning home, he became head of civil defence within the ChRI and then chief of staff of the ChRI military. When the Russians invaded, he co-ordinated the bitter defence of Grozny and then the subsequent – and brilliant – operation to retake the city in 1996. Following that, he assumed a new role as negotiator and peacemaker, reaching the Khasav-Yurt Accord with fellow-veteran, Russian Security Council chairman Alexander Lebed, paving the way for an end to the First Chechen War. He then became ChRI prime minister before winning the presidency in the elections of January 1997.

Nazran, 27 November 1996: Aslan Maskhadov (right), architect of the recapture of Grozny, shakes hands with Russian politician Ivan Rybkin. (© Nikolai Malyshev/Stringer/Reuters/Corbis)

He proved unequal to the challenge of administering Chechnya in a time of peace, though, faced with covert pressure from Moscow, overt challenges from jihadists and the practical problems of rebuilding a country in ruins without revenue. Unable to defeat the Islamic extremists, he tried to conciliate them with a formal introduction of sharia law in 1999, but ultimately he was always a secular nationalist at heart and this was too little, too late. He was caught between an increasingly hard-line Moscow, with the rise of then Prime Minister Putin, and increasingly hard-line jihadists. When Shamil Basayev and Emir Khattab unilaterally invaded Dagestan in 1999, giving Putin the excuse he needed, Maskhadov’s efforts to avert war were doomed.

During the Second Chechen War, Maskhadov did his duty, but his authority over Chechen forces was increasingly weak thanks to the efforts of the jihadists. He tried several times to reopen peace talks, but to no avail. He was equally unsuccessful in seeking to prevent the use of terrorism by Basayev and his allies. In 2005, he died during a commando attack by FSB forces on a hideout in the town of Tolstoy-Yurt. Although accounts are unclear, it is likely he died at the hand of his nephew and bodyguard, Viskhan Hadzhimuradov, who had orders to shoot him rather than let him be captured.

Within three hours, most of the city was in Chechen hands, or at least out of meaningful federal control. Although Russian forces and their Chechen allies (who had a particular fear of being captured) were holding out in the centre, around the republican MVD and FSB buildings and also at Khankala, the speed and daring of the attack led to disarray and downright panic among the numerically superior defenders. There had been some 7,000 Armed Forces and MVD VV personnel in Grozny, but most fled or simply hunkered down in their garrisons. The rebels did execute some collaborators and also in several cases refused to take prisoners, especially of pro-Moscow Chechen forces. However, in the main they were happy to let people flee: they wanted the city and knew large numbers of captives would only tie down their own, outnumbered forces. Nevertheless, perhaps 5,000 federal troops would remain penned within the city, unable or unwilling to try to break out.

Besides, the rebels’ numbers only grew as news of this daring attack spread. Some pro-Moscow Chechens switched sides, some city residents took up arms and further reinforcements arrived from across Chechnya. Desperate to regain the city, the Russians did not wait to gather their forces but instead threw them into the city piecemeal as soon as they became available, allowing Maskhadov to defeat them in detail. On 7 August, a reinforced battalion from the 205th Motor Rifle Brigade was beaten back and another armoured column was ambushed and shattered the next day. On 11 August, a battalion from the 276th Motor Rifle Regiment managed to make it through to the defenders at the centre of the city, delivering some supplies and evacuating a few of the wounded, but they failed to make a real breakthrough.

Khankala airbase, 16 August 1996: federal efforts to capture Grozny’s petrochemical facilities intact were largely in vain. A thick pall of smoke from the Lenin Refinery billows into the air, behind military and police helicopters. (Alexander Nemenov/EPA)

After another week of desultory clashes, the city remained largely in rebel hands. Their numbers had grown to some 6,000 fighters, while around 3,000–4,000 federals were still trapped behind their lines. Lieutenant-General Konstantin Pulikovsky, acting commander of the OGV while Tikhomirov was on a singularly ill-timed holiday, lost his patience and on 19 August issued an ultimatum demanding that the rebels surrender Grozny within 48 hours or an all-out assault would be launched. Even before that ultimatum had expired, next day air and artillery bombardments began and the flow of refugees out of the city increased dramatically. By 21 August, an estimated 220,000 people had fled Grozny, leaving no more than 70,000 civilians in a city which before the war had been home to 400,000.

However, the ability of the Chechen rebels, long described as a defeated and dwindling forces, to retake Grozny had a dramatic impact on Russian politics. Even while Pulikovsky was gathering forces for a massive bombardment of Grozny that would have led to casualties among federal forces, civilians and rebels alike, opinion against the war in Moscow was hardening. Although a number of politicians had long expressed their doubts, the crucial constituency was that of disgruntled Armed Forces officers, especially veterans of Afghanistan, who saw Chechnya as an equally unwinnable and pointless war. Such figures as General Boris Gromov (former last commander of the 40th Army in Afghanistan) had long been calling for a withdrawal. However, the prospect of massive friendly fire and civilian casualties in Grozny galvanized the highest-profile member of this camp, Security Council secretary (and Soviet– Afghan War veteran) Alexander Lebed.

Grozny, 17 August 1996: the speed and surprise of the Chechen counter-attack was such that they were also able to capture several Russian vehicles, such as this T-80 tank – although they rarely lasted long, being magnets for federal rocket and air attacks. (Vladimir Mashatin/EPA)

A blunt, even tactless man nevertheless idolized by the VDV troops who served with him, Lebed was decorated for his service in Afghanistan and had refused to back Communist hard-liners during the 1991 August Coup when they ordered him to deploy his 106th Airborne Division against Yeltsin’s supporters. In the June presidential elections he had come third with 14.5 per cent of the vote, but then threw his weight behind Yeltsin in the run-off poll, in return being appointed to the politically pivotal role of secretary of the Security Council and Yeltsin’s national security adviser. If Yeltsin had thought this would tame the outspoken Lebed, he was wrong, but by the same token Yeltsin was clearly in poor physical health and was worried that the Communist Party might be able to make a renewed bid for power. He was eager, too, to extricate himself from a war that seemed now to have no end.

On 20 August, Lebed returned to Chechnya and ordered federal forces around Chechnya and in the south alike to stand down and observe a ceasefire. Thanks to the assistance of the OSCE, he opened direct talks with Maskhadov and on 30 August they concluded the Khasav-Yurt Accord. This shelved the question of Chechnya’s constitutional status but instead recognized Chechen autonomy and a full withdrawal of all federal forces by 31 December. Further treaties would follow, which would formalize Maskhadov’s willingness to cede claims of outright independence for an end to the fighting and an unprecedented level of autonomy within the Russian Federation. In effect, so long as Chechnya pretended to be part of Russia, Moscow would not try to assert any actual control over it. The First Chechen War was over.

Moscow, 15 February 1999: General Boris Gromov (right) shakes the hand of a Soviet–Afghan War veteran. Gromov was a trenchant critic of the invasion of Chechnya. Not only, in his view, had the Kremlin apparently forgotten the political risks of such interventions; he also felt the Russian military had forgotten the hard-won tactical lessons of the Soviet– Afghan War. (Stringer/EPA)

The ‘hot peace’, 1996–99

For the Grozny operation, Maskhadov had had to assemble a coalition of warlords, commanding some, haggling and negotiating with the rest, including Akhmad Zakayev, Doku Umarov and Ruslan Gelayev. This was a warning sign, that Chechen politics had already become fractured between rival leaders, clans, factions and platforms. Maskhadov would discover that navigating Chechen politics would prove every bit as difficult, as well as dangerous, as fighting the war. In October, President Yandarbiyev formally appointed him prime minister of the ChRI and in January 1997 Maskhadov was elected president in a landslide victory, winning over 59 per cent of the vote. Radical warlord Shamil Basayev came second with 23.5 per cent, Yandarbiyev received only 10 per cent and none of the other 17 candidates could top even 1 per cent. Translating this vote of confidence into real power, though, was the challenge.

In May 1997, Maskhadov travelled to Moscow, signing the final peace accord with Yeltsin. But peace did not mean amity, and not only would there be those in both Russia and Chechnya who wanted to resume hostilities, the challenge of rebuilding this shattered country was formidable. Moscow was not willing to pay reparations and the cost of reconstruction was estimated at $300 million. Unemployment reached 80 per cent and pensions and similar benefits simply were not being paid.

Russian Security Council secretary Alexander Lebed takes a cigarette break, accompanied by his guards, during negotiations with Aslan Maskhadov in Novy Ataghy, 25 September 1998. (Yuri Kochetkov/EPA)

Maskhadov did what he could, but that often was not very much. He could not disarm the warlords, so instead he brought them into the ChRI’s military structure, granting them ranks and official status in the hope that it would tame them. In the main, it did not. Some became virtual local dictators and bandit chieftains, such as Arbi Barayev. A police officer who then became Yandarbiyev’s bodyguard, Barayev set up his own unit during the war, calling it the Special Purpose Islamic Regiment. Even then, though, he became notorious for his bloodthirstiness and his kidnap operations. After the war, although he and his ‘regiment’ were formally inducted into the ChRI Interior Ministry, he set himself up near Urus-Martan and turned to protection racketeering and kidnap for ransom. Barayev refused to subordinate himself to the interior minister or stop his extracurricular activities and in 1998 there was even an armed clash between his men and Chechen security forces in Gudermes. Barayev was stripped of his rank of brigadier-general but continued to have the loyalty of his men and so maintained his personal fiefdom in south-central Chechnya. He arranged for the murder of the head of the police’s anti-kidnap unit and even made two attempts to have Maskhadov assassinated.

Barayev was perhaps the worst of several such local warlords, but his case also illustrates the second key challenge to Maskhadov: the rise of jihadist extremists. After all, while Barayev was not an especially pious man, one reason why he was able to survive as long as he did is that he was able to find common cause with the jihadists against the moderate nationalist Maskhadov. Indeed, Maskhadov blamed Barayev for the kidnap of four Western telecommunications engineers in 1998 (three Britons and a New Zealander) and the likelihood is that they were killed because Osama bin Laden outbid the engineers’ company and wanted them decapitated as a political gesture, instead.

Naurskaya, 11 January 1997: Shamil Basayev on campaign during his bid for the Chechen presidency. He proved a much more effective guerrilla than politician, and his defeat to Maskhadov would help to push him further towards the radical jihadist wing of Chechen politics. (Vladimir Mashatin/EPA)

After all, the influence of the jihadists had increased during the 1990s. In the early 1990s, when travel was easier, a number of ethnic Chechens from Jordan, descendants of earlier refugees and forced migrants, visited the country. One was Fathi Mohammed Habib, an ageing veteran of the Soviet–Afghan War. He settled in Chechnya in 1993 and became the first link connecting wider Salafist extremist Islamic communities with local radicals (whom the Russians call Wahhabis). His most divisive legacy was to invite the Saudi-born al-Qaeda field commander Emir Khattab to Chechnya. Born Thamir Saleh Abdullah Al-Suwailem, Khattab had fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan, where he met Osama bin Laden and became an al-Qaeda troubleshooter, seeing action in Tajikistan, Azerbaijan and the former Yugoslavia. In 1995, he entered Chechnya under the guise of a journalist and began training Chechens as well as distributing funds and weapons provided by al-Qaeda. He was an effective guerrilla commander, but his real strength was as a politician. Thanks to his combination of charisma, experience and resources, he became increasingly close to several key rebel figures, most notably Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev (who awarded him the Chechen Order of the Brave Warrior) and Shamil Basayev. Khattab mistrusted Maskhadov – a sentiment that was heartily returned – and was probably behind several of the assassination attempts against him. However, Khattab was protected by both Basayev and Yandarbiyev, was paying off many of the more mercenary warlords and had his own force of predominantly Arab fighters. Maskhadov could not afford to turn on him.

Khattab made no effort to conceal his true goal, which was not Chechen independence, but to raise a general jihad across the North Caucasus to drive out Christian Russia and create an Islamic caliphate. To this end, he denounced the Khasav-Yurt Accord and actively tried to undermine it. In December 1997, he and his forces even took part, alongside Dagestani insurgents, in a cross-border raid against the 136th Armoured Brigade headquarters in Buynaksk. Maskhadov was forced to deny any Chechens were involved but still he could not afford to trigger a civil war by moving directly against him. The next year Khattab and Basayev formally joined forces, establishing the ‘International Islamic Peacekeeping Brigade’.

Maskhadov tried to hold the country together, but with diminishing success. The economy was still disastrous and people were disillusioned with peace. In July 1998, after the fourth assassination attempt on Maskhadov, he declared a state of emergency, but his capacities to crack down on the estimated 300 separate armed groups numbering a total of around 8,500 men in the country was limited, not least because any that he targeted could turn to the jihadists for support. He then tried to reconcile the increasingly powerful jihadists by going against his own secular tendencies and introducing sharia law, but they were not willing to compromise. Instead, this simply led to splits within the Chechen government and an increasing sense of disillusionment among Maskhadov’s core supporters.

Khattab’s reputation as a ruthless jihadist soon earned him the enmity of the Russians. This soldier, pictured on 31 May 2000 during the Second Chechen War, is loading a shell marked ‘for Khattab’ – although it turned out to be a special operation which managed to kill him by poison instead of any more conventional measure. (Stringer/EPA)

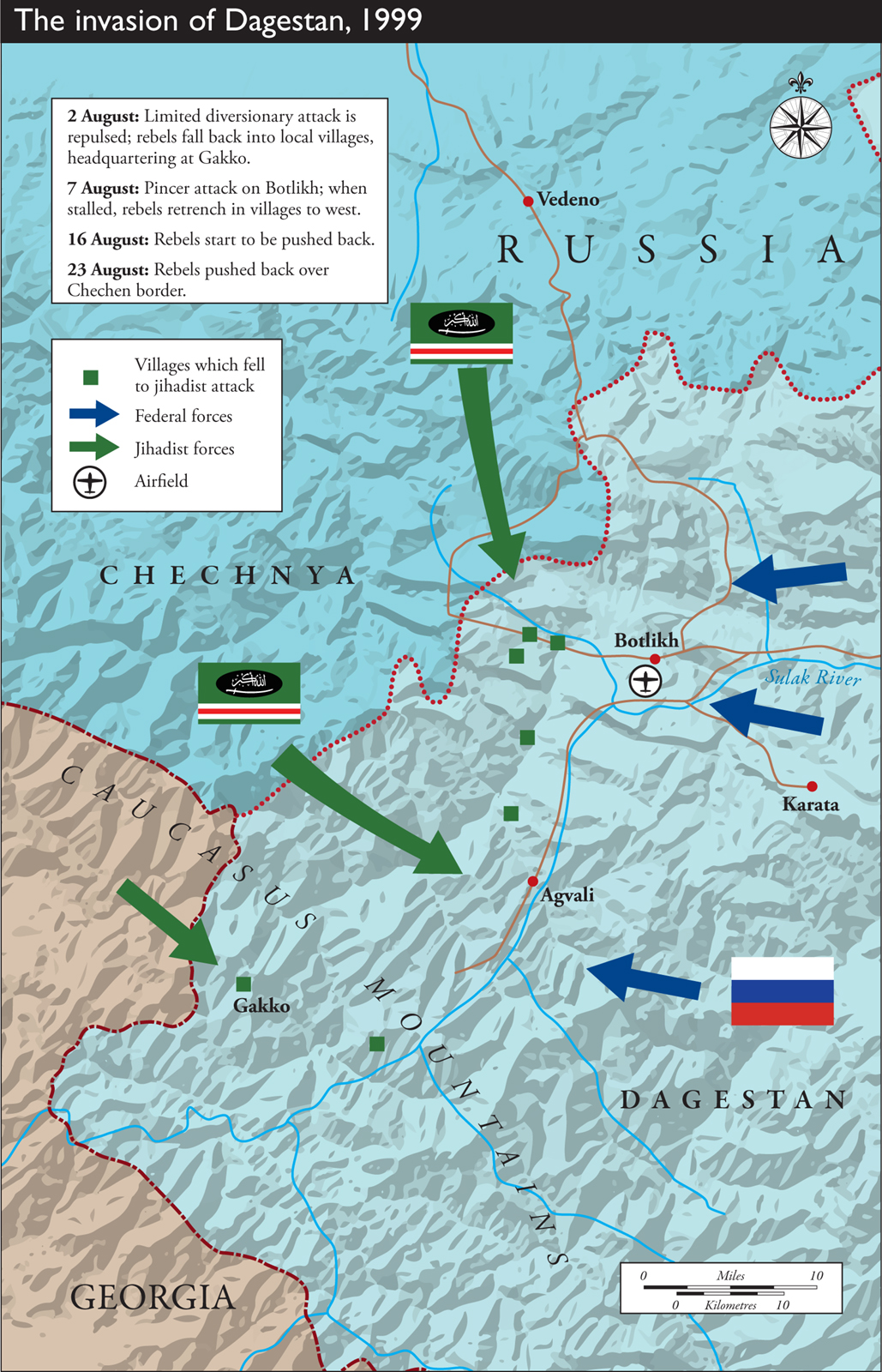

All that was needed was a spark, and Khattab and Basayev were determined to provide one. Neighbouring Dagestan had been experiencing its own rise in anti- Russian and jihadist violence. In April, Bagauddin Magomedov, self-proclaimed ‘Emir of the Islamic Jamaat [Movement] of Dagestan’, and an ally of Khattab’s, had appealed for a gazavat to ‘free Dagestan’. On 7 August 1999, Khattab and Basayev led a mixed force of some 1,500 Chechen, Dagestani and Arab fighters across the border, proclaimed the ‘Islamic State of Dagestan’ and began advancing on Botlikh, the nearest town.

Federal forces were characteristically slow in responding, but – just like those federal forces when they invaded Chechnya – the International Islamic Peacekeeping Brigade would face a rude awakening. Magomedov had assured them they would be welcomed as liberators, but instead they were met not only by tenacious Dagestani police, but also spontaneous resistance from ordinary locals. This helped slow the invaders down long enough for the inevitable deluge of Russian firepower. The attack stalled and in the face of combined ground and air attacks, was forced back into Chechnya. A mix of Armed Forces units, the MVD VV’s 102nd Brigade, Dagestani OMON and Russian Spetsnaz demonstrated a level of competence that had rarely been seen in the First Chechen War. On 5 September, a second incursion was launched further north, striking towards Khasav-Yurt, but this too was blocked after an initial surprise advance, then driven back by local and federal forces. The Russians launched cross-border bombing raids first to try to strike the rebels as they withdrew and then to punish the Maskhadov government for letting this happen, as the attacks shifted to Grozny.

Maskhadov had realized the danger of the attacks and condemned them from the first. He announced a crackdown on Khattab and Basayev and pledged to restore discipline over the warlords. It was too little, too late. After all, there were also rising forces in Moscow looking to reassert control over Chechnya. Khattab and Basayev wanted a war: Vladimir Putin would give them one.

Putin’s war: the invasion

Russia in 1999 was a rather different country from 1994 or even 1996. Yeltsin’s failing health and political grip had led him to search for a successor who could secure his legacy (and look after him and his circle, known as ‘the family’). The chosen figure was a relatively little-known administrator and former spy from St Petersburg called Vladimir Putin. A career officer in the Soviet KGB, in 1990 Putin returned to Russia from East Germany and from 1991 began working within the local administration. He acquired a reputation as a tough, discreet and efficient fixer, working for the mayor before being called to Moscow to work at first in the presidential administration; he became head of the FSB in 1998 and then acting prime minister on 9 August 1999. Yeltsin announced that he wanted Putin to be his successor; on 31 December, he unexpectedly stepped down, making Putin acting president, further strengthening his hand for the March 2000 presidential elections, which Putin won with a comfortable 53 per cent of the vote.

A nationalist and a statist, Putin made no secret of his desire to reverse the weakening of central control under Yeltsin and his determination to make the world recognize Russia as a great power once again. He had also enjoyed a meteoric rise thanks to powerful patrons within the system but was relatively unknown to the Russian public; he needed some high-profile triumph, some dramatic opportunity to prove that the Kremlin was now occupied by a determined and powerful leader. Chechnya seemed perfect for this. While Khattab and Basayev were giving him the grounds to tear up the treaty with Grozny with their incursion into Dagestan, he began instructing his generals to prepare for a second war. Contingency plans for an invasion had, after all, started to be developed in March and for over a year the Russian military has been actively wargaming invasion plans. In July 1998, for example, an exercise across the North Caucasus saw 15,000 Armed Forces and MVD troops practise fighting against ‘terrorists’.

St Petersburg, 28 January 2000: While still only acting president, Vladimir Putin throws a handful of earth into the grave of Major-General Malofeyev, killed in action in Grozny. Putin was accompanied by Defence Minister Igor Sergeyev (on his right). Putin generally avoided attending funerals which might otherwise draw attention to casualties, but a general’s was an inevitable exception. (Anatoly Maltsev/EPA)

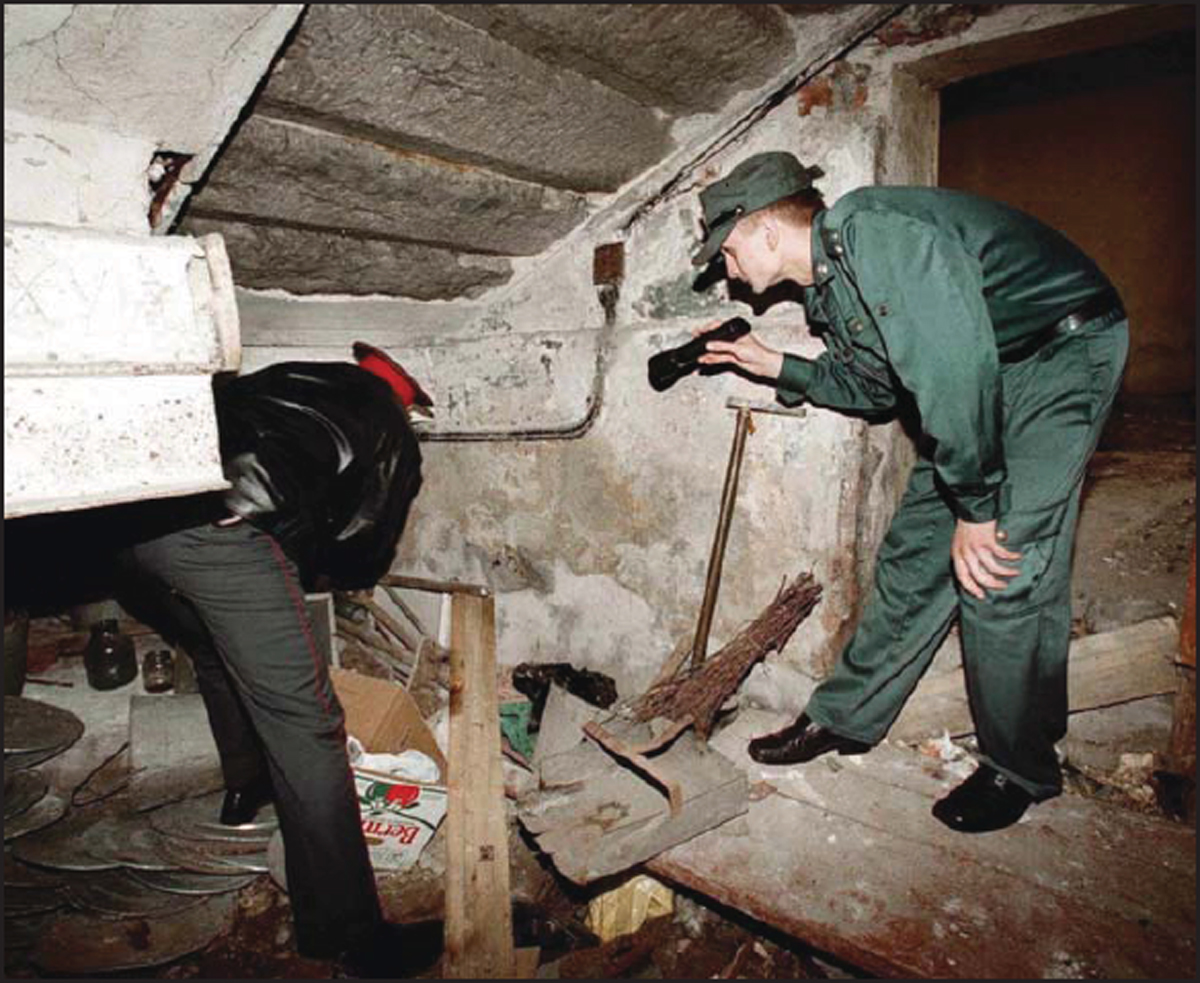

St Petersburg, 15 September 1999: the Chechen wars brought terrorism to Russia’s cities. Following mysterious attacks in Moscow the week before, police search the attic of an apartment building in response to a telephone threat. Such incidents helped swing public opinion behind the tougher Kremlin line. (Anatoly Maltsev/EPA)

Putin was determined that this time the Russians would muster adequate forces, prepare properly and plan for a guerrilla war. Furthermore, the Russian public would be readied for the inevitable casualties. In September, a mysterious series of bombs exploded in apartment buildings in Moscow (twice), Buynaksk and Volgodonsk, killing 293 people. Still to this day there is controversy over these bombs. There is certainly a serious body of belief that these were provocations arranged by the Russian security agencies, not least given that a similar bomb was found by chance in Ryazan and connected to the FSB, which then claimed this had been a training drill. Nevertheless, the Kremlin presented this as an escalation of the Chechens’ terror campaign and at the time many ordinary Russians were frightened and angry, looking to the government for security and revenge.

Zandak, 30 October 1999: a Russian soldier scrambles forward alongside a BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicle as federal forces push into south-western Chechnya during their encirclement of Grozny in 1999. (Dmitri Korotaev/EPA)

The bombing campaign which had followed the Dagestani incursion was expanded steadily, hammering Chechen cities until the flood of refugees into Ingushetia was exceeding 5,000 people a day. Overall, perhaps a quarter of the total remaining Chechen population would flee and while this put great pressure on neighbouring regions to deal with the influx of refugees, drawing on Mao’s famous analogy that guerrillas move among the population like fish in the sea, it also drained much of the ‘sea’ to allow the Russians to spot the ‘fish’ that much more easily. ‘Filtration camps’ were established behind the army lines, to hold and process refugees, identifying suspected rebels for interrogation and detention.

On 1 October, Putin formally declared Maskhadov and the Chechen government illegitimate and reasserted the authority of the Russian Federation over its wayward subject. Meanwhile, federal forces started moving. Instead of the foolhardy direct assault of the first war, the Russian plan was a staged and methodical one. The first stage was as far as possible to seal Chechnya’s borders, while forces were assembled. All told, these numbered some 50,000 Armed Forces troops and a further 40,000 MVD VV and OMON personnel, some three times as many men as had taken part in the 1994 invasion. Overall command went to Colonel-General Viktor Kazantsev, commander of the North Caucasus Military District.

Then, Moscow announced that in the interests of securing the border and establishing a ‘cordon sanitaire’, units would have to take up positions which ‘in a few cases’ would be ‘up to five kilometres’ (3 miles) inside northern Chechnya. Then, saying that the terrain meant that it was impossible to secure this line, they warned that they would advance as far as the Terek River, occupying the northern third of the country. By 5 October, they had taken these new positions. Fighting was at this stage sporadic and localized, in part because Maskhadov was still trying to make peace. Again, the Russians were in no rush. They spent the next week consolidating their forces – and ignoring Maskhadov’s overtures – until 12 October, when they crossed the Terek, pushing towards Grozny in three fronts. The Western Group pushed through the Nadterechnaya district until it reached the western suburbs of Grozny; the Northern Group pushed down across the Terek at Chervlennaya; while the Eastern Group swung past Gudermes and likewise moved to flank Grozny from the east.

As they advanced, the federal forces met relatively little resistance, with local settlements’ community leaders often protesting their loyalty and claiming that there were no rebels in their areas. These settlements would be searched for weapons and fugitives and then MVD forces would establish guard posts. Where the Russians did come under fire, they would typically fall back and liberally use artillery and air power to clear potential threats and obstacles in their path before continuing. On 15 October, they seized the Tersky Heights, which commanded Grozny from the north-west. Accepting that no truce was possible, Maskhadov declared martial law and called for a gazavat against the Russians. Within the next few days, the Russians slowly encircled the city, taking outlying towns and villages such as Goragorsky (one of Shamil Basayev’s bases) and Dolinsky. Meanwhile, Grozny itself came under sporadic but heavy bombardment, including strikes by OTR-21 Tochka short-range ballistic missiles with conventional warheads, one of which hit a marketplace on 21 October, killing more than 140 civilians.

Gudermes, 20 November 1999: a Russian officer inspects a Chechen flag taken as a trophy. The city fell relatively easily during the Russian invasion, not least thanks to the defection of the Yamadayevs. Hence the soldiers’ rather more relaxed posture, including the Russian flag. (Sergei Chirikov/EPA)

Again in contrast to the first war, the Russians were willing to leave Grozny until they had consolidated their rear. In this, they were also the beneficiaries of the years of in-fighting within Chechnya, which had broken the discipline that had held the rebels together before. Gudermes, for example, fell to the Russians to a large extent because of the defection of the Yamadayevs, the dominant local family of the Benoi teip, who had their own private army (known officially as the 2nd ChRI National Guard Battalion). Pragmatists, the Yamadayevs had been very much on the secular, nationalist wing of the rebels. In 1998, they had clashed with Arbi Barayev and units of the jihadist Sharia Regiment and might have destroyed them, had pressure not been brought to bear to arrange a ceasefire. Squeezed between an increasingly jihadist rebel movement and the approaching federal forces, the Yamadayevs opted to make a deal with the Russians. Their forces would become the basis of the Vostok (East) Battalion, set up by the GRU (Military Intelligence) and commanded first by Dzhabrail Yamadayev and then his brother Sulim. They would not be the only defectors.

Through November and December, the Russians concentrated on taking and holding urban centres, forcing the rebels either to cede them and be forced into the countryside during the bitter North Caucasus winter, or else to stand and fight where they could be battered by federal firepower. The village of Bamut, which had held out for 18 months in the first war, fell on 17 November, bombed and shelled to rubble. Argun fell on 2 December, Urus-Martan on 8 December. In December, the federal forces turned to Shali, the last rebel-held town outside Grozny, which had fallen by the end of the year, although efforts were made by the rebels to retake it and Argun in January.

Sulim Yamadayev, resplendent in dress uniform, confers with a Russian officer at Khankala. The Yamadayevs were a powerful family who defected to the federal side in 1999 with their private army, which became the Vostok Battalion. Sulim Yamadayev was shot and killed in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, in March 2009. (Kazbek Vakhayev/EPA)

The third battle of Grozny

The defenders had had time to fortify Grozny. They dug trenches, laid mines, built fortified positions inside some buildings and booby-trapped others. However, the Russians were also far more prepared for the latest battle of Grozny. Chief of the General Staff General Anatoly Kvashnin, who had been responsible for the initial and disastrous New Year’s Eve attack on Grozny in 1994, was determined to atone for his earlier failure. Beyond a few skirmishes and probing raids, though October, November and much of December, the Russians confined themselves to bombardments using aircraft, Scud and OTR-21 ballistic missiles, artillery and TOS-1 fuel air explosive rockets. Only some 40,000 civilians were left in the ruins of the city, along with perhaps 2,500 rebels under Aslambek Ismailov. On 5 December, the Russians starting dropping leaflets, urging those remaining to leave by 11 December, while opening up a safe corridor for them. Although many Chechens mistrusted this offer, not least as the Russians checked the documents of those leaving, there was no mistaking that the Russians were preparing for an assault.

Grozny, 22 January 2000: MVD VV personnel fire on Chechen positions. The figure in the centre has a GP-30 grenade launcher attached to his AK-74 rifle, providing useful additional firepower in short-range combats as it has an effective range of some 150 metres. Just visible to the right, one man carries a disposable RPG-26 anti-tank missile, commonly used to destroy rebel positions inside buildings. (© Vladimir Suvorov/epa/Corbis)

They mustered some 5,000 troops for the assault itself: the 506th Motor Rifle Regiment, two MVD VV brigades and in total some 400–500 Spetsnaz, who were particularly used for reconnaissance, sniper and counter-sniper duties. They were backed by extensive artillery elements and OMON (who would be used for rear-area security). In what was a portent of the future, they were also supported by some 2,000 pro-Moscow (or at least anti-rebel) Chechen fighters in a militia commanded by Beslan Gantemirov, a convicted embezzler whom Yeltsin had pardoned in return for his becoming the mayor of Grozny in the new regime. He recruited a force of volunteers, patriots, mercenaries, opportunists and criminals whom the federals trusted little – the MVD only issued them out-dated AKM-47s from reserve stocks, which had been phased out of military use in the 1980s – but who nevertheless knew the city and were fierce and flexible, like their ChRI counterparts.

The siege forces started moving in on 12 December, infiltrating reconnaissance elements to draw rebel fire and then hammering the rebels with airstrikes and artillery. By the end of the next day, Khankala airbase was back in federal hands. One exploratory push into Minutka Square by the 506th was ambushed, although the new T-90 tank proved much more resistant to RPGs than the old T-80 had, one surviving seven hits. The fighting was fierce: about a quarter of the soldiers of the 506th were killed or wounded, so it was withdrawn and replaced with fresh troops of the 423rd Guards ‘Yampolsky’ Motor Rifle Regiment. In the main, though, the Russians were content to draw their ring slowly closer. That put the pressure on the Chechens to seek to break out or distract the federal forces with other attacks. This they did, in one case managing to take back the outlying village of Alkhan-Kala, but each time they did so, they took casualties they could not afford and, thanks to the siege of the city, could not replace.

On 15 January, Kazantsev decided the ground had been prepared well enough. Federal forces moved into the city along three axes, facing both tough rebel resistance from the 2,500 or so remaining defenders as well as the problems in trying to move through a city not only liberally strewn with mines, traps and unexploded ordnance but also pounded into rubble. This, along with the Russians’ new-found caution, kept advances slow. Even so, the rebels were able frequently to infiltrate the Russian lines, lay more mines and stage lightning attacks, in one case managing to kill Major-General Mikhail Malofeyev, commander of the Northern Group, in the assault. Nevertheless, the best they could do was slow the Russian advance. By the end of the month, running low on men, ground to retreat into and ammunition, the rebel commanders opted to abandon the city, regroup at the village of Alkhan-Kala south-west of Grozny and make for the highlands in the hope of regrouping and following the same trajectory as in the First Chechen War. Already, though, the new divisiveness of the rebel movement was becoming visible, as Ruslan Gelayev – following a disagreement with the jihadist elements of the rebel command – withdrew his forces from the city, allowing them to slip out in small groups all around the perimeter.

Grozny, 21 February 2000: a Russian sniper patrols the streets after the second Russian conquest of the city. In contrast to the first invasion, this time at least Russian forces had adequate winter clothing and their snipers had been given extra training to be effective in an urban environment. (EPA)

At the end of January, as federal forces continued to grind into the centre of Grozny, the rebels attempted to break out of the city under the cover of a heavy storm. Some tried to bribe their way through Russian lines, others to slip out hidden among groups of refugees, while others tried to use stealth when possible, firepower when not. This would be a disastrous and humiliating flight, as rebels blundered into minefields outside Alkhan-Kala, were scoured by artillery-fired cluster rounds (in some cases bringing Russian fire down onto civilians, too) and were harried by helicopters and Spetsnaz. Of the perhaps 1,500 rebel fighters left in Grozny, some 600 were killed, captured or wounded in the retreat, including Ismailov. The survivors largely scattered, some simply drifting home, most heading south.

Meanwhile, on 6 February the Russian formally declared Grozny ‘liberated’. Even so, the city was in ruins and it would take a month for OMON and Gantemirov’s militia to mop up a few remaining hold-outs in the city and a year for the bodies from the battle to be found and buried. Although on 21 February the traditional Defender of the Fatherland Day parade was held in central Grozny, supposedly as a mark of the return of normalcy, this would be a brutal, vengeful time, as apartments were looted, men accused of being rebels were dragged off to a filtration camp (or simply shot in the street) and stray rebels continued to mount bomb and sniper attacks. The 21,000 civilians remaining of the city’s Soviet-era population of 400,000 were often forced to camp out in the ruins, eating whatever they could scavenge.

Putin’s war: the pacification

Grozny was the last major urban centre to fall and the federal forces quickly moved towards consolidating their positions across the country. Even while Grozny was under siege, the Russians had been pushing forwards on two separate fronts. The first was in the south, where Armed Forces units were trying to break into the southern highland strongholds. The second front was in the rear, where the MVD was establishing not just its own network of strong-points and garrisons of VV and OMON personnel, but also launching aggressive patrols and search operations to locate rebels, arms caches and safe houses. With the shattering of resistance in Grozny, these other federal forces were well placed to block, intercept, capture or eliminate larger concentrations of rebels.

In April 2000, Colonel-General Gennady Troshev was appointed head of the OGV. Although the Russians were still estimating that there were some 2,000–2,500 rebels, they were satisfied that they were largely scattered around the country and posed relatively little serious challenge to federal control. They were both wrong and right. Wrong in that rebels still could cohere in units numbering several hundred and engage in operations which could cause serious Russian casualties. Right, though, in that these attacks never posed a serious threat to the federal forces’ overall grip on the country. For example, one of the last major, pitched engagements of the war took place in March, at Komsomolskoye, a village south of Grozny and the home village of warlord Ruslan Gelayev. An OMON unit from Russia’s Yaroslavl Region first encountered Gelayev and his men there, as they prepared to break through to the cover of the Argun Gorge. Once their numbers became clear – estimates ranged from 500 to 1,000, but the real figure was closer to the lower end of that scale – the OMON settled for trapping them in the city and calling for support. The OMON were promptly reinforced by an MVD VV regiment and OMON and special police units from Irkutsk, Kursk and Voronezh. After four days of almost constant bombardment, including sorties by Su-25 ground-attack jets and salvoes from TOS-1 220mm multiple rocket launchers firing thermobaric rounds, the federal forces stormed the village. The fighting was fierce and unpredictable, even though a wounded Gelayev managed to slip out of the village, and it took another week and a further bombardment before Komsomolskoye was pacified. This was one of the bloodiest battles of the war, with the official butcher’s bill being 552 Chechens and more than 50 Russians. The village itself was all but levelled; journalist Anna Politkovskaya called it ‘a monstrous conglomerate of burnt houses, ruins, and new graves at the cemetery’, though she put the blame not just on federal forces but also Gelayev, wondering ‘how could he ever think of taking the war home, to Komsomolskoye, knowing in advance that his own home village would be destroyed?’

The TOS-1 ‘Buratino,’ here shown on parade in Moscow, is a formidable weapon carrying 30 thermobaric fuel-air explosive rockets on a converted T-72 chassis. (Goodvint/CC BY-SA 3.0)

This was a serious clash, but hardly something to make Putin think twice. Ambushes continued, sometimes substantial ones in which the Chechens could muster as many as 100 fighters and could inflict distinct losses, but with some 80,000 federal soldiers still present in-country and the Kremlin keeping a much tighter control of the media reporting on the war, nothing generated the kind of public and elite dismay as had been present during the First Chechen War. Furthermore, Putin moved quickly to re-establish the forms of constitutional order so as to give the appearance of normalization. In May, in a half-step forwards, Moscow announced that it was taking over direct rule of Chechnya. This at least ended its previous ambiguous state of being a conflict zone essentially outside the regular laws of the state and was a prelude to establishing a local puppet government. In June 2000, Putin appointed Akhmad Kadyrov as the interim head of the Chechen government. Kadyrov was the most prominent of the former rebels who had defected to Moscow. The Chief Mufti of the ChRI, he was a prominent rebel during the First Chechen War but he was an outspoken critic of the Wahhabist jihadi school and this new generation regarded his moderate Islamic views with equal suspicion. In 1999, he and his son Ramzan broke with the ChRI and joined the federal side, bringing with him Kadyrov’s personal militia. This force of Kadyrovtsy (‘Kadyrovites’) was to expand dramatically, not least as other deserters from the rebel cause flocked to join. After all, Kadyrov still retained considerable moral authority, paid well – and was known to ask no questions as to their previous activities. In another attempt to portray the conflict as all but over, or at least no more than a police action now, from 2002 successive OGV commanders came from the MVD VV, not the Armed Forces.

OGV commanders in the Second Chechen War

| 1999 | Colonel-General Viktor Kazantsev (Armed Forces) |

| 2000 | Colonel-General Gennady Troshev (Armed Forces) |

| 2002 | Colonel-General Valery Baranov (MVD) |

| 2004 | Colonel-General Yevgeny Baryayev (MVD) |

| 2006 | Major-General Yakov Nedobitko (MVD) |

| 2008 | Major-General Nikolai Sivak (MVD) |

Assailed not just by federal forces but Chechen militias such as the Kadyrovtsy, the Yamadayevs’ Vostok Battalion, as well as a separate Zapad (West) Battalion recruited by the GRU as a counterweight, the rebels were increasingly pushed onto the defensive and limited to small-scale raids and ambushes. They turned ever more to terrorist tactics and even suicide attacks (never previously a feature of Chechen guerrilla struggles). Controversially, this extended to terrorist attacks against Russian civilians, albeit probably without Maskhadov’s approval. In October 2002, for example, some 40 terrorists seized the Dubrovka Theatre in Moscow, taking some 850 hostages. After two days of failed negotiations, a narcotic gas was pumped into the building, which was then stormed by the Al’fa counter-terrorist team. The terrorists were killed, but so too were 179 hostages, almost entirely because of adverse reactions to the gas. Later, in September 2004, another effort was made, when 32 jihadist terrorists seized School Number One in the North Ossetian town of Beslan on the first day of the new school year. Of the 1,100 hostages taken, most were children. On the third day of the ensuing siege, when one of the terrorists’ bombs exploded, the building was stormed: 334 hostages died, including 186 children. However, while during the First Chechen War the authorities had been willing to compromise, under Putin the Kremlin took a tough line and continued its campaign to pacify Chechnya. If anything, he used it as the reason to intensify his efforts; after Beslan, he said: ‘We showed weakness, and weak people are beaten.’

In March 2003, a new Chechen constitution was ratified by referendum, explicitly declaring the republic part of the Russian Federation, with Akhmad Kadyrov being formally sworn in as Chechen president later that year. While the rebels were down, they were not yet out, though. Attacks continued, most strikingly on 9 May 2004. Akhmad Kadyrov was receiving the salute at Grozny’s Dinamo stadium during the annual Victory Day parade when a bomb exploded, killing him along with a dozen others.

Gudermes, 19 October 2003: Akhmad Kadyrov during his inauguration ceremony as Chechen president, standing between the flags of Russia (left) and the Chechen Republic (right). (Eduard Korniyenko/EPA)

Although his son Ramzan, who commanded the Kadyrovtsy, was too young formally to succeed him as president – Interior Minister Alu Alkhanov was sworn in as a stopgap replacement – in effect he took over his father’s role. In keeping with the rich Chechen tradition of the feud, he also redoubled his efforts to wipe out the remnants of the rebel movement. As it was, though, the rebel movement was already a shadow of its former self. Their leaders killed one by one, the rebel movement shrank and radicalized, with more and more nationalist guerrillas simply drifting quietly home when their hopes of a free Chechnya receded and their leaders increasingly seemed more interested in a greater holy war. Federal forces in-country were reduced to the newly formed 42nd Motor Rifle Division and MVD VV assets, but along with the Kadyrovtsy these were more than enough for the task. Meanwhile, the real focus of insurgency shifted to new conflicts elsewhere in the North Caucasus. Ingushetians, Dagestanis, Kabardins and other local peoples began challenging Moscow’s rule and corrupt and ineffectual local governments.

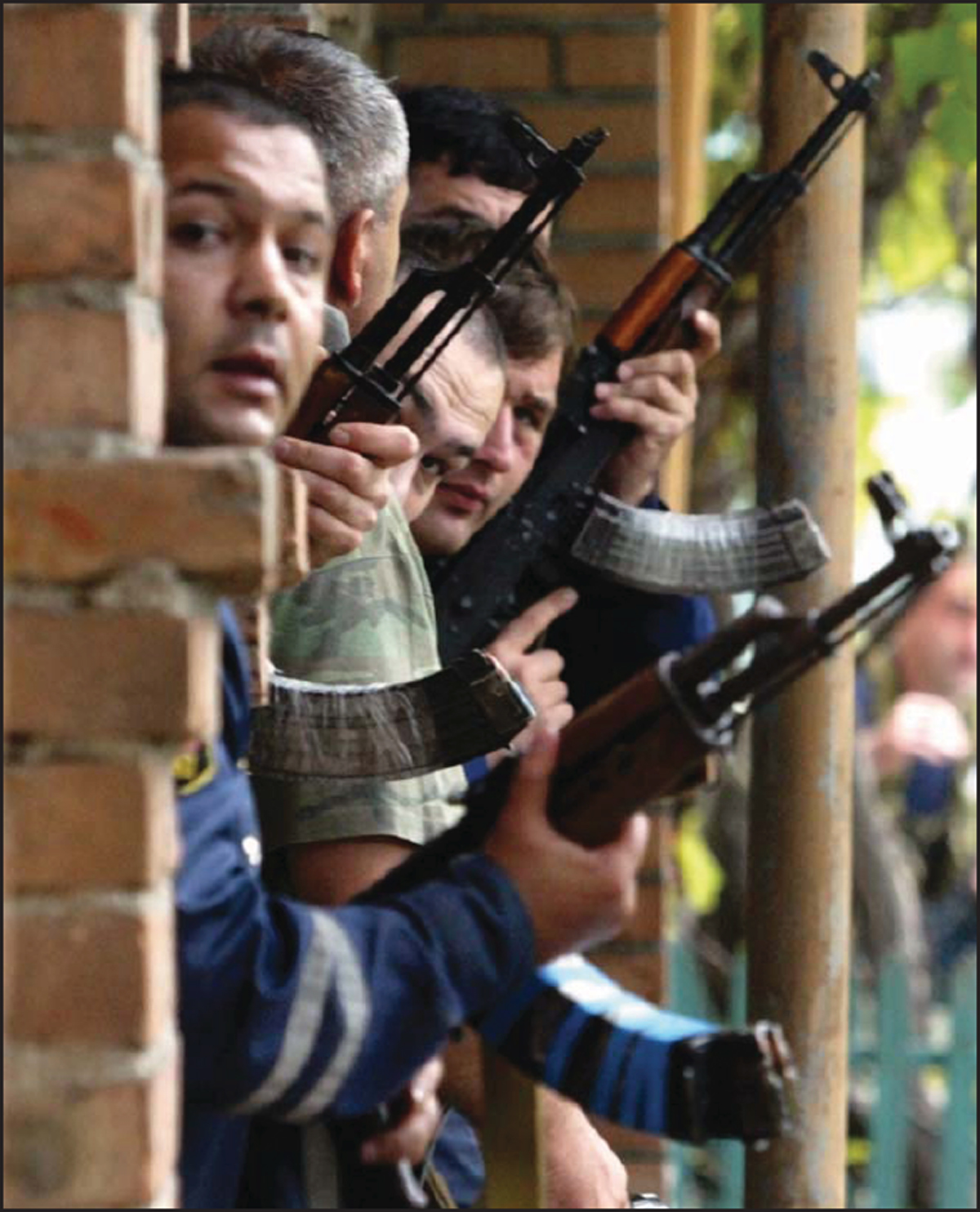

North Ossetian security forces peer round a wall during the Beslan siege on 3 September 2004. Local forces were generally enthusiastic but poorly trained, disciplined and armed. They carry dated AK-47 rifles and the figure at the front is actually a traffic policeman rather than from the regular patrol-guard service or the military. (© VIKTOR KOROTAYEV/Reuters/Corbis)

Having made a surprise visit to the republic, President Putin, flanked to his left by then-deputy prime minister Ramzan Kadyrov, watches the opening of the Chechen parliament in December 2005. On his right is Chechen President Alu Alkhanov, who would soon give up his office to allow Kadyrov to replace him. (© STRINGER/RUSSIA/Reuters/Corbis)