Portrait of a soldier

Sergeant Pavel Klementyev

It was hell. But then I went back.

– Pavel Klementyev, 2009

Growing up in Kursk in eastern Russia, Pavel Klementyev’s only contact with Chechens was a couple of men who would occasionally appear in a local market, selling fresh fruit that one simply could not buy in the drab local stores. After all, born in 1976, Pavel was a product of the last years of the USSR, when the economy was sliding into crisis, Party propaganda a hollow farce and the black market the only way anyone not in the elite could get anything. He was a mediocre student at school and – as he was not smart enough to get into university, well-connected enough to get someone to overlook him, or sick enough to be exempted – when he was 18 he was called up into the Russian military. It was then April 1994 and Russia was not at war, so while he felt some trepidation about his two years in the ranks, not least having heard about the brutal bullying of dedovshchnina from friends’ older brothers, he approached it with a degree of equanimity. He had, after all, been raised on the heroics of the Red Army at the battle of Kursk in 1943 – the largest tank battle in history – and while national service might not be something people looked forward to (‘life is a book’, the saying went, ‘and military service is two pages ripped out of it’), it was also regarded as an inevitability.

None of the higher-prestige services seemed interested in him, so Pavel ended up in the motor-rifle troops of the Armed Forces, the infantry. He was packed off to a training base at Kovrov, in the Russian interior, where he went through a six-month training programme that seemed to involve a great deal of drill together with random violence and abuse from the older soldiers. The Russian Armed Forces were in terrible financial straits, though, so ammunition was tight (he only fired 20 live rounds with his AK-74 rifle) and some weekends the draftees were forced to ‘volunteer’ to do manual labour for local companies, which paid the officers for their services. Even so, he proved unexpectedly to thrive in the environment and was selected as one of the conscripts to receive the additional training to become a sergeant.

In October 1994, he completed his training and was assigned to the 255th ‘Stalingrad-Korsunsky’ Guards Motor Rifle Regiment, part of the 20th Guards Motor Rifle Division based in Volgograd (formerly known as Stalingrad) in southern Russia. He found garrison life a mix of the tedious and the fulfilling, especially when he was attached to the regiment’s reconnaissance company. The scouts (razvedchiki) considered themselves a cut above the standard infantry and their brotherhood shielded Pavel from some of the abuses that were commonplace in the unit. Even so, he experienced and witnessed officers extorting money or food from soldiers, widespread pilfering of everything from cookware to weapons and beatings of new recruits by senior conscripts as much as anything else just because they could. As he recounts it, he engaged in some of these activities, simply ‘because if you don’t, you stand out, and that’s dangerous’.

In November, the regiment was redeployed to Kizlyar, where it would in due course become part of Lieutenant-General Lev Rokhlin’s eastern taskforce. It was immediately clear that this was more than just a routine or precautionary move. Suddenly, soldiers started receiving live ammunition for shooting practice and there was a flurry of horse-trading between officers of the 255th and other units being left behind to ensure that the regiment had a full complement of working vehicles. Even then, though, the general assumption was that they were being sent to Dagestan to frighten the Chechens rather than invade. Even so, Pavel recalled one captain in the regiment, a veteran of the Soviet–Afghan War, getting very drunk one night and warning the men that ‘this is how it begins’.

He was, of course, right. The 255th deployed with the rest of Rokhlin’s force and found itself taking part in the ill-starred New Year’s Eve assault on Grozny. Fortunately, their mission of seizing the central hospital complex in the north of the city meant they avoided the worst of the fighting. However, Pavel’s reconnaissance company was detailed to swing round the perimeter along which the 255th had dug in and gauge defences along the way towards the centre. His platoon, mounted in BMP-2 infantry combat vehicles, faced multiple ambushes within half an hour, losing one vehicle to an RPG round and then a second to improvised Molotov cocktails which filled the engine intakes with burning petrol. Although a combination of the BMP-2’s 30mm autocannon and the platoon’s personal weapons allowed them to disperse the attacks, it was soon clear that the company would not make it into the centre without dying a death of a thousand ambushes. They withdrew and painted a suitably exaggerated tale of hundreds of heavily armed Chechens to explain their failure to complete their mission.

Grozny, 1 May 2005: a Russian Orthodox priest blesses federal personnel. The experiences of the First Chechen War reminded the high command of the importance of morale and motivation, and as a result, in the quest for a new cohering ideology after the fall of Communism, the Orthodox Church – and Russian nationalism – have become increasingly important. (© Reuters/Corbis)

Pavel and the 255th would subsequently complete that journey into downtown Grozny, although not before it had been all but levelled by artillery and airpower. He spent the next six months in a mix of garrison duties and counter-insurgency sweeps, during which he became hardened to such tactics as blasting buildings with tank and artillery fire to neutralize a single sniper, regardless of the presence of civilians. Nevertheless, nothing compared with the crucible that had been those first days in Grozny and although he would be involved in perhaps a dozen engagements, he would tend to shrug them off as hardly worth mentioning.

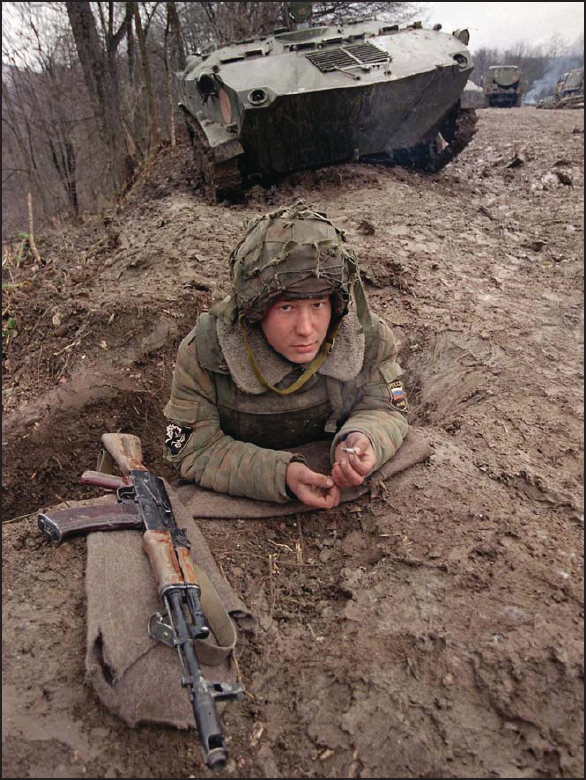

Outskirts of Grozny, 29 November 1999: a federal combatant smokes in a trench while his AK-74 rifle lies ready beside him. The BTR-D vehicle behind him, originally designed for airborne assaults, was used in Chechnya for both troop transport and specialized command and communication roles. (© ALEXANDER GREK/epa/Corbis)

His conscription term ended at the end of March 1996 and ‘in three days, I went from a war zone to home’. However, he found life back home unsettling and dissatisfying. This was a time when the Russian economy was in dire straits, jobs were few and pay often minimal or in arrears. He spent a few months helping out at his father’s car-repair business but ultimately did not know what to do. He was becoming irritable, drinking whenever he could afford it and one night got into a brawl in which, by his account, he almost killed a man because he was bragging about pulling strings to get out of national service.

His father, who had been a transport policeman, encouraged him to join the militsiya, the police. Sensing that it might give him the structure and purpose he was lacking in civilian life, Pavel applied and was successful. After training, he spent two years as a beat Patrol-Guard Service officer in Kursk before getting a transfer to the OMON riot police at the end of 1999. When the Second Chechen War began in December, many OMON units – including Kursk’s – were instructed to send detachments to join the federal forces. The ‘OMONovtsy’ were promised combat pay, but Pavel said he would have volunteered regardless:

‘There was suddenly such a savagery in me, such an anger and a desire to teach the Chechens a lesson.’

He returned to Grozny in February 2000, just as it again fell to the Russians. However, his first major action was in March when he took part in the Komsomolskoye operation against the forces of the warlord Ruslan Gelayev. His OMON unit was one of several brought in first to besiege and then to storm the village, after a four-day bombardment. By his own account, he was in the thick of the fighting, which was bloody, brutal and often at ‘bayonet range’ in his words. Pavel, while admitting taking part in the systematic looting of what buildings still survived, remains guarded as to whether he also took part in the widespread practice of shooting captive rebels.

Nevertheless, by his own account Komsomolskoye ‘burnt the anger out of me’. He served a year in Chechnya with the Kursk OMON before returning home – without the promised combat pay, but enriched by looting and taking occasional bribes – and continuing his service with the police. He was awarded the MVD’s Medal ‘For Merit in the Activities of Special Units’ for his time in Chechnya.