The world around war

The world looks on in horror

We have strongly and consistently urged all sides to seek a political solution. A purely military solution is not possible. And so we urge Russia to take meaningful steps toward a political solution.

– US State Department spokesperson, December 1999

In an age when conflict has become a question of international law, media coverage and diplomacy, the two Chechen wars demonstrate both the limits of external constraints and the degree to which a still-powerful and above all determined nation can flout foreign opinion if it is willing to pay the price. Arguably, Moscow’s willingness to invade Georgia in 2008 and annex Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014 reflected the extent to which it was emboldened by the lack of meaningful international response to its tactics in Chechnya. Nevertheless, the conflict certainly had an impact on Russia’s place in the world, not least in its short-lived rapprochement with the United States following the 9/11 attacks, when for one brief moment there seemed to be a common front against a common enemy.

Moscow, 15 May 2002: Defense Ministers (from left to right) Chi Haotian (China), Mukhtar Altynbayev (Kazakhstan), Esen Topoyev (Kyrgyzstan) and Sergei Ivanov (Russia) attend the session of defence ministers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (© Reuters/CORBIS)

During the First Chechen War, the Russians tried to present themselves as fighting for order against gangsters and extremists, but this played rather poorly in the rest of the world. US President Bill Clinton warned Yeltsin that he risked feeding an ‘endless cycle of violence’ and human-rights organizations were especially outspoken in their criticisms. Human Rights Watch, for example, declared that ‘Russian forces have shown utter contempt for civilian lives in the breakaway republic of Chechnya’.

The chaos and criminalization of Chechnya in the inter-war era did mean that however opposed the international community might have been to Russian invasion and the methods used, Moscow could present itself as the guardian of order. The incursions into Dagestan had also demonstrated that Maskhadov either could not or would not restrain the jihadist commanders and that this was a problem that could well grow. However, Moscow’s attempts to present this as simply an ‘anti-terrorist campaign’ failed to win much sympathy in the West. During his presidential election campaign, US president-to-be George W. Bush warned in 1999 that ‘even as we support Russian reforms, we cannot support Russian brutality’. Next year, speaking at the United Nations, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said that the Chechen conflict had ‘greatly damaged Russia’s international standing and is isolating Russia from the international community’.

Only China was supportive of Russia’s position from the first, not least because it had its own concerns about separatists as well as an impatience with Western criticisms of its own human rights record. In 1999, for example, Beijing stated that ‘the Chechen problem is clearly an internal affair of the Russian Federation and [China] supports the actions of the Russian government in fighting terrorist and separatist forces’. Next year, on a visit to Moscow, Chinese Defence Minister Chi Haotian went further, offering ‘full support for the efforts which are being made by the Russian authorities in conducting the antiterrorist operation in Chechnya’.

However, the al-Qaeda 9/11 attacks in 2001 gave Moscow a perfect opportunity to reframe its campaign as simply one more battlefield in a global struggle against extremist forms of Islam. Putin was among the first world leaders to contact President Bush to express his outrage at the attacks and to offer support. That day, he went on Russian television to hammer home the point: ‘What happened today underlines once again the importance of Russia’s proposals to unite the efforts of the international community in the fight against terrorism, against this plague of the 21st century … Russia knows first-hand what terrorism is, so we understand more than anyone else the feelings of the American people.’

He was as good as his word in supporting the US invasion of Afghanistan – even as many within the military elite smugly anticipated Washington finding itself sucked into the same morass that had greeted Moscow when the Soviets invaded in 1979 – and offering intelligence-sharing in the fight against international terrorists. However, this era of amity was not to last. With the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan and the beginning of the campaign to shatter al-Qaeda as a coherent force, ironically enough that organization’s ability to provide fighters and money to support the struggle in Chechnya rapidly dwindled. Furthermore, Washington began to lose patience with Moscow’s attempts to caricature all the rebels as wild-eyed jihadists and its often-unsubtle manipulation of the intelligence it did share.

Ultimately, US–Russian relations would worsen, with Putin’s efforts to retain control over the country and resist democratizing pressures, as well as his aggressive foreign policy, increasingly alarming Washington. Although a level of pragmatic intelligence sharing and co-operation continued, this was never as open and productive as originally hoped, as witness the intelligence gaps through which the Chechen Tsarnayev brothers – who bombed the Boston marathon in 2013 – slipped.

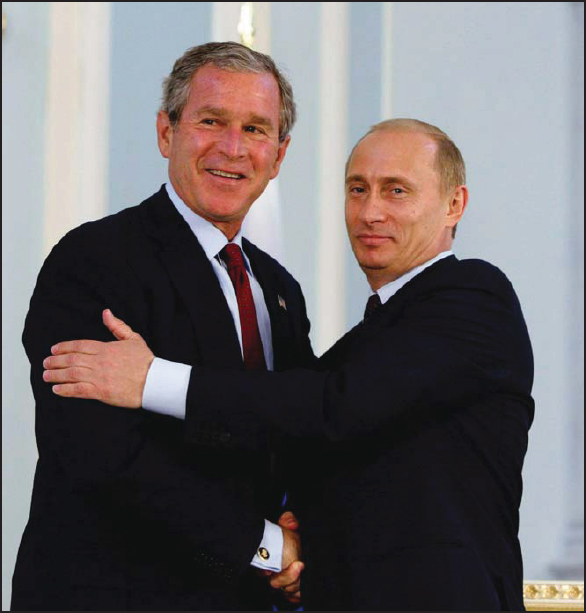

Vladimir Putin undoubtedly sought to capitalize on US appreciation for his support over 9/11 to legitimize his operations in Chechnya. Here, he and United States President George W. Bush are holding a joint press conference in St Petersburg in 2003, after the ratification of the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty. (© Reuters/Corbis)

Just as Moscow was eager to present the Chechens as agents of international jihadist conspiracy, so too during a period of poor relations with neighbouring Georgia, the Russians were keen to present Georgia as an ally of the rebels. It is certainly true that Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge region, which abuts onto Chechnya, was used in the 1990s and 2000s by rebels as a refuge in which to rest and recover. This may have sometimes been with the knowledge and acquiescence of the Georgian government, but it is unclear how often this was the case. The Pankisi Gorge was a notoriously lawless region where the government’s authority often counted for little and where two-thirds of the population were ethnic Kists, kin to the Chechens. Unsurprisingly, many Chechen refugees headed there, among whom was a minority of fighters. In August 2002, Russia bombed a village over the border and eventually the Georgians deployed over 1,000 troops into the Gorge to restore order and arrest or expel fighters, as much as anything else to forestall any more extensive Russian response. After all, Russian defence minister Sergei Ivanov gave a heavy-handed hint referencing the US invasion of Afghanistan: ‘The international community has just crushed the nest of international terrorism in Afghanistan … We must not forget about Georgia nearby, where a similar nest has recently begun to emerge.’ Ultimately, Russo-Georgian relations would still lead to war, in 2008, but at least the pretext was not Chechnya.

Russian troops in Ingoeti, Georgia, on 15 August 2008, waiting by their BMP-2 personnel carrier. The white armbands were commonly used to distinguish Russian forces from enemies who might be wearing similar camouflage. (© Donald Weber/VII /Corbis)

Especially during the First Chechen War, Moscow claimed not only that it was fighting to topple a criminal regime in Grozny but also that this regime was connected to and using the services of the wider Chechen criminal diaspora throughout Russia. In 1996, for example, Anatoly Kulikov claimed that strike teams of Chechen gangsters were being dispatched to cities across Russia, planning ‘the complete destabilization of Russia’. This was a striking but also entirely fictitious claim. Indeed, while the Dudayev regime was thoroughly criminalized, there was actually a clear and widening division between the networks operating in Chechnya and those outside the republic. Nikolai Suleymanov, the powerful Chechen gangster known as ‘Khoza’, described this as the ‘two Chechnyas’. While there were connections between the two, largely through kinship, in the main Russian-based gangs were very keen to limit their links with their counterparts in the homeland. In part, this was because they feared being targeted by the authorities as potential fifth columnists and in part a genuine cultural divide between those Chechens who were wheeling and dealing in a larger, predominantly Russian context and those who stayed locked within the tighter and smaller world of tradition and kin. In 1995, for example, Dudayev sent representatives to meet with kingpins in the bratva (‘brotherhood’) – a broad term to mean Chechen organized crime in Russia as a whole, not a specific gang – in the northern Russian town of Petrozavodsk. He hoped they would bankroll his regime, but not only did they refuse, they also, at a subsequent gathering in Moscow, banned direct transfers of money, men or weapons to the rebels.

Akhmed Zakayev is pictured at the World Chechen Congress in Pultusk, Poland, on 18 September 2010. (©AGENCJA GAZETA/Reuters/Corbis)

This division only grew under Putin, when it was made very clear by the authorities that any hint of support for the rebels would bring savage reprisal. Given in any case that the bratva were unimpressed by the growing Islamic radicalism within the ChRI, they were even less inclined to help. Instead, they concentrated on their own pursuit of money and power in the Russian underworld. The irony was that where there were verified cases of organized crime factions selling weapons to the rebels, they were actually ethnic Russian gangs selling guns to Chechen rebels for them to shoot at fellow Russians.

On the other hand, there is a distinct ethnic Chechen diaspora outside Russia providing more support for the rebels. There are some 20,000 ethnic second-, third- or fourth-generation Chechens in Syria and 34,000 in Kazakhstan, but also a substantial diaspora in Turkey (where there may be up to 150,000) and across Europe. There has been a ‘ChRI government in exile’ in existence since 1999, as of writing presided over from asylum in the United Kingdom by moderate nationalist ‘chairman of the council of ministers’ Akhmad Zakayev, formerly Maskhadov’s foreign minister. However, its actual influence is marginal. Instead, the current jihadist Caucasus Emirate (IK) movement has been able to gain funds and material support from Turkish Chechens in particular, sometimes voluntarily and sometimes extortion. A series of murders of prominent Chechens in Turkey accused of fundraising for the IK has been blamed on Moscow or Grozny, but this has not been proven.