An explosion of superheroes from Contest of Champions #1 (1982, art by John Romita, Jr.).

f your name were Marv Wolfman, imagine how tough things could get during your junior high school recess in Flushing, Queens. But even worse, perhaps, would be having your name restricted by the Comics Code Authority.

f your name were Marv Wolfman, imagine how tough things could get during your junior high school recess in Flushing, Queens. But even worse, perhaps, would be having your name restricted by the Comics Code Authority.

DC Comics published an on-again, off-again mystery anthology entitled The House of Secrets, whose anodyne title was prescribed by the Code. Writer Len Wein, who contributed a variety of scripts to the series, pointed out, “For years, under the Code, you couldn’t use the word don’thorror,” you couldn’t use ‘terror.’ And so for a while we fudged around the edges. You know there was House of Mystery, there was House of Secrets, but nothing that was House of Scary anything.” In 1969, young comics writer Marv Wolfman contributed a story to House of Secrets: “It’s my real name,” he said. “God knows, nobody would choose that.” Back then, the writers of the anthology tales were never given a story credit. The title’s editor, Gerry Conway, wanted to acknowledge his bullpen in some way, and had the narrator of the comic book refer to a tale told to him by a “wandering wolfman.” When that issue of House of Secrets was submitted to the Comics Code Authority, they demanded that “wolfman” be removed, citing its restrictions against werewolves and other lycanthropes. “What if it’s the guy’s actual name?” asked Conway. In that case, the Code Authority gave a practical dispensation; if DC pasted up a blurb to that effect, they would relent. And that’s how Marv Wolfman got his first writing credit in a comic book.

Gene Colan brought literature’s most famous vampire back from the dead in the pages of The Tomb of Dracula (1974).

In the wake of the relaxation of Code restrictions, Marvel Comics opened the crypt doors for every conceivable monster and ghoul in full-color and black-and-white magazines (Tales of the Zombie #1, 1975)—sometimes even crossing over to each other’s titles: The Tomb of Dracula #18 (1974).

If The House of Secrets had been able to keep its powder dry two more years, it wouldn’t have mattered. When the Comics Code Authority made its revisions in February 1971, it broadened the possibilities of reintroducing horror (and terror) into the world of comics: “Vampires, ghouls, and werewolves shall be permitted to be used when handled in the classic tradition, such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and other high caliber literary works.” The crypt gates were flung wide open and the tomb-raiding began.

Marvel Comics exploited the possibilities with abandon almost as soon as the Code ruling was announced. Under its new editor-in-chief, Roy Thomas, they floated the idea of a scientific vampire supervillain called Morbius in the pages of The Amazing Spider-Man. The character was enthusiastically embraced by readers, so Marvel quickly moved ahead with various showcases and titles featuring a shuffling swamp-vegetation humanoid called “The Man-Thing”; a wolfman in Werewolf by Night; the godfather of all vampires in The Tomb of Dracula; a motorcylist daredevil with a flaming skull for a head in Ghost Rider; the eponymous Monster of Frankenstein; a mummy character, conceived as a mummified Nubian slave revived in 1972; Brother Voodoo, who fought the undead in Haiti; the self-evident Zombie; several daughters and sons of Satan; even the Golem, that statuesque defender of the Jewish people, was revived to fight the after-effects of the 1973 Yom Kippur War in the Holy Land.

Morbius had one fang in the supervillain world, another fang in the monster world (The Amazing Spider-Man #101, art by Gil Kane); the swamp monster Man-Thing had a long history at Marvel, beginning in the b&w magazine Savage Tales (May 1971).

The monster explosion also occurred in a series of parallel publications produced by a new venture of Marvel’s publishers: black-and-white magazines, which were larger in size and volume and utterly unrestricted by the Comics Code Authority. As tantalizing and as unfettered as these horror omnibuses were, they didn’t last out the 1970s. The monster characters found a more congenial home in the full-color comics, which makes a kind of sense, since the monstrous Hulk and the Thing had already straddled both the superhero and the monster genre; even Batman was at his best as a creature of the night. Speaking of bat-men, the most successful of Marvel’s horror ventures was The Tomb of Dracula, which continued an epic and convoluted narrative over seven years, guided inestimably—and almost entirely—by the artist Gene Colan (the only comic book artist who could draw fog convincingly) and its scriptwriter, none other than Marv Wolfman. The Ghost Rider spun his wheels into a couple of movies in the 21st century and Blade the Vampire Hunter, who was created for the Tomb of Dracula series, also became a Hollywood fixture in three separate films.

DC Comics was clearly outdrawn, as it were, by Marvel’s buckshot approach to monsterdom, but the revised Code also cleared the way for Len Wein and artist Bernie Wrightson to expand on a character they had created in 1971 for The House of Secrets: another sentient vegetative humanoid called Swamp Thing. Swamp Thing was given his own title in 1972. Along with the Man-Thing at Marvel (in a very different, but equally imaginative series of tales), there was something about sentient vegetative humanoids that leant themselves to wonderfully metaphoric suspense tales: perhaps it was all the concern about the environment and ecology in the mid 1970s. In any event, Ghost Rider, Man-Thing, Swamp Thing, and even Dracula have survived the ’70s surge and been successfully assimilated into the universes of their respective publishers.

Marvel tossed a platoon of new characters at readers in the early 1970s: the Haitian Brother Voodoo (Strange Tales #169, art by Gene Colan); the fast-paced Ghost Rider (Marvel Spotlight #5, art by Mike Ploog); the Golem (Strange Tales #174, art by John Buscema); and the kung fu-inspired adventures of Shang-Chi (art by Paul Gulacy).

As much as the younger writers and artists of both companies may have enjoyed tackling the forbidden creatures of yesteryear (the titles were almost uniformly given to up-and-coming creators), the vast expansion of these titles had as much to do with business practice as it did with the new freedoms of the Comics Code. By 1969, Marvel publisher Martin Goodman had shed his onerous newsstand distribution deal that had corseted the company for years. Space was finally freed up to give almost all the main characters their own books; combined with the new ventures into horror, within three years Marvel had almost quadrupled the number of titles they put out every month. Many were anthologies and reprints of both superhero and monster books from the early 1960s, but just as many were new characters, such as the science fiction-tinged Warlock or the kung fu masters Shang-Chi or Iron Fist. Guided by Roy Thomas, Marvel also dove headfirst into the licensing business, an area previously reigned over by Dell or Gold Key Publishing. The pulp sword-and-sorcery pioneer Conan the Barbarian began his long and violent history with Marvel in 1971, and even Doc Savage made a brief, if well-drawn, appearance in 1972. Not to be outdone, DC Comics licensed Tarzan, revived the Captain Marvel character in a series called Shazam! (the “M-word” was now off-limits), and reintroduced the Shadow to comic books in some very atmospheric tales. (At the time, Stan Lee joked that if DC licensed the pulp hero the Spider, Marvel would have to license the Black Bat.) But Marvel really hit pay dirt when Thomas had the foresight to license an under-promoted science fiction movie before its 1977 release: Star Wars.

TOP: Pulp characters from the 1930s were licensed by Marvel and DC and briefly joined the superhero stable: Doc Savage meets the Thing, while Batman historically crosses paths with his inspiration, the Shadow. BOTTOM: Artist Wally Wood brought an elegant style to one of the first comic books based on a toy, Captain Action #1 (1968). The action figure took on Superman in toy stores, too (original packaging).

Star Wars #1 (art by Howard Chaykin), a collaboration between Marvel and Lucasfilm, began a successful decade-long run in spring 1977.

Licensing was also extended beyond properties and characters that existed in the print media. In the 1960s, there had been limited spin-offs that provided certain toys with their own comic books. Captain Action, a 12-inch doll who could wear the costumes of other superheroes, was the granddaddy of all action figures (the first in fact to use that term) and had a brief run at DC Comics. But, from the late 1970s on, there were more complicated relationships between toy companies and comic book publishers. A posable robot called Rom the Space Knight was licensed to Marvel to create stories that would provide both a narrative and a buzz for the product (the comic was more successful than the toy); The Micronauts comic book was a Marvel initiative, where the comic book piggybacked on a line of miniature toys originally produced by a Japanese company. In the early 1980s, the Hasbro toy manufacturer acquired another line of Japanese toys—little robots which could transform themselves into cars, planes, toaster ovens, you name it—and worked with Marvel and some of its best writers, including Denny O’Neil, to create a mythos and a backstory for the toys: it became The Transformers, a dominating titan in the industry. The relationship between toys and comics was no mere child’s play: the respective industries would work together into the 21st century, creating complex, multi-platform launches that would encompass endless narratives supporting a battalion of robots, aliens, and action figures who marched down the aisles of K-mart and Toys “R” Us for decades.

These expansive relationships with large corporations were manifestations of the fact that both Marvel and DC Comics would become part of corporations themselves and would undergo tremendous structural transitions as a result of corporate buy-outs. Marvel would become a subsidiary of Cadence Industries, a publishing company that had gotten its start in pharmaceuticals, and DC Comics would be taken over by Kinney National Company, a conglomerate built on parking lots and construction, which would soon metamorphose into Warner Communications. The pressure to produce was tremendous; neither of the corporate entities was run by folks who came out of the thirty-odd-year-old comics industry; soon the carefully cherished characters and narratives had to square off against a new adversary: the Bottom Line. As a parting shot to his Distinguished Competition, publisher Goodman raised the price of his comics from fifteen to twenty-five cents and doubled the page count; when DC followed suit, Goodman immediately reversed his policy, cut back the size of the books and charged twenty cents per copy. DC hung in there for a while with the twenty-five-cent price tag, but had been essentially undercut in the marketplace, and was now stuck with overpriced comic books. Kids could buy five Marvel books for a dollar, rather than four with the DC Comics logo. DC never quite recovered.

By the time the Watergate scandal had ousted Richard Nixon from the White House, another authority figure had been routed: DC had ceded their three-decade market share to Marvel Comics. It would require a game-changer to reshuffle the deck. Luckily, DC Comics owned the first, and most super, game-changer of them all.

Early publicity shots of Superman: The Movie put Christopher Reeve in NYC’s Central Park; in the film, he appears as Clark Kent with Margot Kidder as Lois Lane.

n the entire contents of Mario Puzo’s submitted 500-page screenplay for the first major motion picture based on Superman, there was not one word as important as the one that director Richard Donner ultimately had emblazoned on his office wall:

n the entire contents of Mario Puzo’s submitted 500-page screenplay for the first major motion picture based on Superman, there was not one word as important as the one that director Richard Donner ultimately had emblazoned on his office wall:

The “Verisimilitude” sign in director Richard Donner’s office.

Superman’s journey to the multiplex was one of his more arduous adventures. Toward the end of 1973, two foreign film producers, Alexander Salkind and his son Ilya, were contemplating their next project. They had just put together a mammoth international version of Dumas’ The Three Musketeers (so mammoth, it would eventually be released in two parts, an unprecedented event in itself) and were looking for something equally adventurous and monumental. Although, rumor has it, the elder Salkind had never heard of Superman, he was persuaded by his son that it was just the property they needed, and the Salkinds set about acquiring the rights from Warner Communications.

It may be difficult to imagine a time when there had never been a full-length, big-budget Hollywood film about a superhero, but with the exception of a hastily patched-together 1966 movie with the Batman television cast, the Salkinds’ project was without precedent. Luckily, the producers had the temerity (if not quite the means) to break the mold in a superlative way. In the four years it took them to negotiate the rights from Warner Bros., commission a screenplay (initially from Mario Puzo, famed for his novel and screenplay for The Godfather), acquire a director (several had come and gone before Richard Donner signed), cast the picture, and begin shooting at England’s Pinewood Studios in March 1977, there was a parallel phenomena of dumping superheroes onto the primetime television schedule (as well as Saturday morning television cartoons). Spider-Man and Captain America fared poorly, while Wonder Woman (embodied with statuesque pep by Lynda Carter) came off more successfully. (The Incredible Hulk launched a successful television run right before Superman debuted in movie theaters.) An ill-conceived Doc Savage motion picture was barely released in 1975. The superhero brand had been relegated to the living room console by this kind of exposure, so the road to Superman’s multi-million-dollar motion picture showcase was littered with skeptics.

Jerry Siegel couldn’t even have been counted on as a skeptic; Superman’s co-creator was an outright antagonist to the project. In 1975, as press releases and promotional gimmicks kept perpetuating the eventual release of a Superman film, Siegel sent a nine-page letter out to the media, detailing his outrage at National Periodicals and the profligate expenditures on the upcoming film: “I, Jerry Siegel, the co-originator of SUPERMAN, put a curse on the SUPERMAN movie! I hope it super-bombs. I hope loyal SUPERMAN fans stay away from it in droves.… You hear a great deal about The American Dream. But Superman, who in the comics and films fights for ‘truth, justice and the American Way,’ has for Joe and me become An American Nightmare.” The letter detailed every perceived ignominy suffered by Siegel and Shuster—but the basic thrust was true: since their failed lawsuit in the late 1940s, neither man had an ongoing sustainable career in comics—Shuster, in fact, was almost legally blind and living in near-poverty. And their ongoing credit as Superman’s creators hadn’t appeared in print for a quarter of a century.

The media was slow to pick up the story, but artist Neal Adams, who had been an outspoken advocate for creators’ rights for years, teamed up with Golden Age pioneer Jerry Robinson, who was also head of the National Cartoonists Society, to orchestrate a series of press conferences, media appearances, and general drum-beatings that might force Warner Communications’ hand. Thanks to Adams and Robinson, it turned out to be a very popular story—the resonant appeal was obviously in the common-man-against-oppression trope that had served Superman so well during the Depression. As 1975 drew to a close, a series of back-and-forth negotiations between Warner and Robinson/Adams (representing Siegel and Shuster) ramped up, all in the shadow of the upcoming film: “That worked in our favor,” said Robinson. “That gave us even more leverage. [Warner] didn’t want any bad publicity on eve of the movie.”

The small screen embraces superheroes—more or less: Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno share duties on The Incredible Hulk; CBS’s Spider-Man in front of NYC’s Twin Towers; Lynda Carter radiated strength and beauty as Wonder Woman.

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s cause was vigorously taken up in 1975 by Neal Adams and Jerry Robinson, supported by the National Cartoonists Society.

A settlement was reached: Siegel and Shuster were to receive $20,000 each a year, for life; they would get incremental raises; medical coverage; a one-time bonus of $17,500 each; and, most important—an issue haggled over most intensely—their credit as Superman’s co-creators would be restored. Warner held out on one point—any credit on toys and action figures was out of its hands—but the important elements were in place. The deal was concluded on the afternoon of December 23, 1975, making it a Christmas present of Dickensian proportions. Siegel and Shuster joined Robinson at his West Side apartment that night, along with other champions of their cause, and watched the CBS Evening News together as Walter Cronkite broke the scoop on the deal, which Robinson had personally let him in on. “And finally, truth, justice, and the American Way won out,” intoned Cronkite, as everyone lifted their champagne glasses. “I’ll tell you,” recounted Robinson, “There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

Meanwhile, as they say, production work on the film was taking an unbearably long time. Puzo’s immense script draft proved unwieldy, so the Salkinds brought in Robert Benton and David Newman, who had not only written the screenplay for Bonnie and Clyde, but the book to a witty if short-lived Broadway musical called “It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman” in 1966. As the team (along with Newman’s wife, Leslie) tried to focus the screenplay and make it compelling to contemporary America, the Salkinds searched in vain for their leading man. It was a near-impossible task, as the role was considered too demanding (so said Robert Redford), too ridiculous (Paul Newman’s reason for saying “no”), too square (thereby knocking sexy Burt Reynolds out of competition), too All-American (sorry, Sylvester Stallone—who was dying to play the part), and too unremunerative (James Caan priced himself out). Months dragged on, as Olympic decathlon champ Bruce Jenner, Muhammad Ali, Perry King, and even someone’s dentist were all considered and rejected.

Alexander Salkind decided to put his quickly evaporating chips on another part of the table; with a stellar supporting cast, he could raise money and credibility quickly. Marlon Brando accepted $3.7 million to play Superman’s father, Jor-El, plus exorbitant percentages of the gross receipts; he would wind up working only twelve and a half days and tweaked the press by claiming he wanted to play the part as a floating green bagel, arguing that Superman’s background needn’t be humanoid at all (however kooky, Brando made an undeniably sensible point). Gene Hackman was signed to play Superman’s arch-foe, the bald-pated Lex Luthor, although to maintain some fleeting sense of dignity (Hackman was embarrassed to be in a comic book movie), he refused to shave his head. The clout of Brando and Hackman allowed Salkind to leverage more money, and to save some overhead, he moved his production to eight sound stages in England’s Shepperton Studios, which came with a tax credit. Director Richard Donner was brought on board and he firmly insisted on that “verisimilitude”: “It’s a word that refers to being real … not realistic—yes, there IS a difference—but real,” explained Donner. “It was a constant reminder to ourselves that, if we gave into the temptation we knew there would be to parody Superman, we would only be fooling ourselves.”

As 1975 stretched into 1976 and into 1977 without a starting date, Donner enlisted screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, whose witty way with pulp material had enlivened several James Bond movies, to focus the script one more time: it was now being planned by the Salkinds as a two-part movie with a $26.5 million budget. Still, the project was lacking a star and a convincing technical method that would get Superman airborne. On a flier, as it were, the producers took one last desperate look at a skinny Juilliard-trained actor from New York, who had some Broadway and soap opera experience. Christopher Reeve nearly didn’t make his meeting with Salkind in New York, because, rather like Hackman, he didn’t think the material was serious enough. But his good looks convinced Salkind to arrange a screen test, where, apparently, it was his charming approach to Clark Kent that put him over the top. George Reeves (no relation) barely suggested a difference between Superman and his mortal disguise on the television show, but Reeve was inspired by the bumbling, bespectacled Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby. For Reeve, Clark Kent was “a deliberate put-on by Superman … there’s some of him in all of us. I have a great deal of affection for him—it’s not just that he can’t get the girl, he can’t get the taxi.” Reeve saw himself as “custodian of Superman in the 1970s” and seemed privileged to play the character. When he signed on for a mere $250,000 at the end of February 1977, everyone involved in the project sighed a superbreath of relief.

Two box-office powerhouses lent their clout to the Superman project: Marlon Brando as Jor-El and Gene Hackman as Lex Luthor (from Superman II).

Filming finally began in March 1977, when the last, essential challenge was solved: how to make it credible that Superman could fly. After testing a variety of different effects to no avail, the producers were persuaded by an optic effect created for the film called Zoptic, which allowed Reeve to lie ramrod straight on a gurney, while the specially designed zoom lenses did the rest; no pesky wires were required. Filming stretched on into fall 1977, and then into early winter 1978. Donner essentially had to edit two films at once, and was in constant budget battles with his producers; luckily—in the midst of being sued by both Brando and Mario Puzo—the Salkinds managed to offer premium film composer John Williams enough money to score an unforgettably heroic soundtrack.

Donner’s completed film took the entire Superman mythos seriously without compromising its giddy charm as an essential myth in American popular culture. Superman was stylistically divided into thirds. The first part is icy, deliberate, science fiction on the minimalist, sleek, crystalline planet Krypton, where Jor-El, after sentencing three criminals to the Phantom Zone, vainly attempts to get his elder colleagues to heed his warnings about his planet’s imminent destruction. He wearily, but stoically, sends his tiny young son to the planet Earth, via a shimmering, jagged pod.

Once young Kal-El arrives on earth, the second third of the story—his upbringing in Smallville—takes on the yearning frontier spirit of a John Ford movie, as if it were art directed by Andrew Wyeth. When he turns eighteen, Clark Kent discovers his alien roots via a hologram of his father, who imparts his wisdom in theological tones:

Live as one of them, Kal-El, to discover where your strength and your power are needed. Always hold in your heart the pride of your special heritage. They can be a great people, Kal-El, they wish to be. They only lack the light to show the way. For this reason above all, their capacity for good, I have sent them you … my only son.

A high-flying Christopher Reeve in the 1978 film blockbuster.

Then, the story turns to Metropolis—location filming in New York City proved to be a very persuasive substitute—where Clark’s vocation at the Daily Planet and his subsequent unrequited affair with Lois Lane was rendered with all the spark and bite of a cynical 1970s urban film, which Superman was, after all. In an impressive blend of action, adventure, comedy (nicely rendered largely by Hackman’s Luthor who, despite his claims of having “the greatest criminal mind of our time,” certainly hires the two most incompetent cohorts in history), and romance, the movie soars to a thrilling conclusion. The romance was charmingly supplied by Reeve and his co-star, Margot Kidder, who brought to the screen the kind of sparking banter usually found only in Cary Grant/Katharine Hepburn films.

Proceeded by an ad campaign that riskily taunted audiences that they would “believe a man can fly” and despite its beleaguered history, Superman opened across the country on December 15, 1978, to largely enthusiastic reviews—most of them concurring that Reeve had pulled off a titanic task with persuasive flair. By spring 1979, most of the cast and crew returned to begin filming the sequel, much of which was already in the can. Although Donner had had enough dealing with the Salkinds and was replaced by Richard Lester, the sequel further refined the elements that had worked in the first place and in some cases—superior fight scenes with the power-enhanced criminals who escaped from the Phantom Zone, for example; an existential dilemma faced by Superman that stretched all the way back to Greek tragedy—actually improved on the original.

Still, the original Superman had a fortress full of happy endings for everyone: for the Salkinds, whose film made nearly $300 million worldwide, providing a profit even after all the settled lawsuits; for Reeve, who went from Hollywood Superman to Hollywood superstar; for audiences, who really did believe a man could fly; for Warner Bros., which mined three sequels out of the project; for fans, who felt that their standard bearer had been rendered in a cinematic version that was worthy of his eminence. But the happiest ending of all happened at the very beginning, some three minutes into the film: two weary comic book creators had the chance to see a boldly animated credit soar across the screen:

The opening credit that made comic book fans across America cheer.

One of the sexiest panels in comic book history, thanks to John Romita; blind date Mary Jane Watson reveals herself to Peter Parker (The Amazing Spider-Man #42, November 1966).

eath had been a part of the Spider-Man legend since the web-slinger’s debut, casting its shadow over the life of Peter Parker’s Uncle Ben and thereby setting into motion Spider-Man’s heroic obligation. When Death came knocking again at The Amazing Spider-Man, twice—first literally, then figuratively—in the early 1970s, it would irrevocably change the tone of superhero comic books.

eath had been a part of the Spider-Man legend since the web-slinger’s debut, casting its shadow over the life of Peter Parker’s Uncle Ben and thereby setting into motion Spider-Man’s heroic obligation. When Death came knocking again at The Amazing Spider-Man, twice—first literally, then figuratively—in the early 1970s, it would irrevocably change the tone of superhero comic books.

The soap-opera drama that made Spider-Man so unique and so compelling in the mid 1960s often revolved around Peter Parker’s love life—or lack thereof. But, eventually, Peter’s “dumb luck” came up sevens and he had to choose between two of the most attractive and desirable women in the world of comic books. Peter first met Gwen Stacy when he moved on to college in 1965. She was a cool, platinum blonde (insofar as comic books could render platinum), with bangs, a black headband, and go-go boots. She was Peter’s intellectual equal, but seemingly miles beyond him on the social scale. Mary Jane Watson, on the other hand, was originally set up for Peter as a blind date; he spent countless issues avoiding her, only to discover she was a bombshell (“Face it, tiger … you just hit the jackpot!” she famously exclaimed to him at the end of The Amazing Spider-Man #42). Mary Jane was a redhead, a free-swinging model and would-be actress, bursting with snappy repartee. She was “kooky”—back when that word was a signifier for the counterculture.

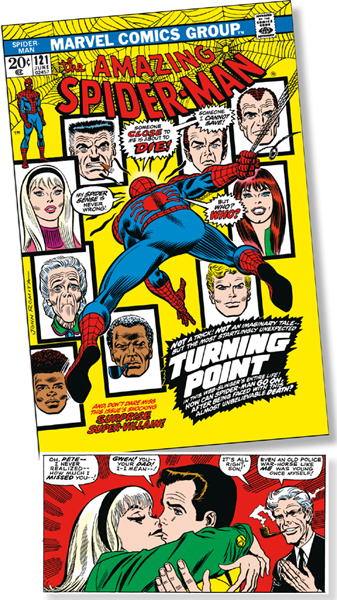

TOP: Death and dismay were always part of the Spider-Man soap opera (The Amazing Spider-Man #121, art by Gil Kane). BOTTOM: Peter Parker finds love in the arms (and lips) of Gwen Stacy (The Amazing Spider-Man #59).

If they had been cast in a Hollywood movie of the 1950s, Gwen would have been played by Grace Kelly, Mary Jane by Shirley MacLaine. In their graphic incarnations, they were impeccably rendered by veteran artist John Romita, who had cut his teeth on the Marvel romance comics of the late 1950s. This only made sense, as “M.J.” and “Gwennie” were the Betty and Veronica to Peter Parker’s Archie Andrews.

By the beginning of 1973, Peter had more or less chosen Gwen. Stan Lee had moved off his fabled scripting chores on the title to spend time in his new role as Marvel’s publisher, and Gerry Conway took over the reins. Conway was another member of the new generation of comic book writers, one of the youngest; in fact, he took on The Amazing Spider-Man while barely out of his teens. Conway’s relative youth served him well; he was essentially the same age as Peter Parker and trying to make a go of it in Manhattan himself in the early 1970s. Conway was particularly sympathetic to Parker’s various predicaments.

Will it be Gwen Stacy or Mary Jane Watson? Only their hairdressers—and Stan Lee—know for sure.

When Conway started on the series, there was a sense that the Spider-Man stories needed to be changed up. John Romita thought it would help if one of the characters was forced to walk the plank. Stan Lee voted for Peter’s geriatric and solicitous Aunt May, but she had been on the Grim Reaper’s dance card since the beginning. Aunt May’s death would be sad, thought Conway; but he was going for tragic. And so, in The Amazing Spider-Man #121, the ground was laid for a genuine game changer in the world of comic book fantasy, amazing or otherwise.

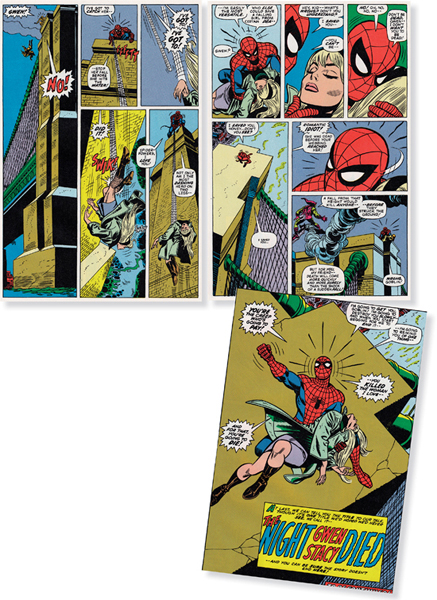

The Green Goblin had always been one of Spider-Man’s major villains, but, as the father of Peter’s best friend, he was more insidiously involved in Parker’s private life. Because of that connection, the Goblin learned of Spider-Man’s alter ego and abducted Peter’s girlfriend to exact his revenge; this impending peril was the reason most superheroes refused to divulge their secret identities. The Goblin tossed Gwen Stacy off the tower of a Manhattan bridge; Spider-Man shot his webbing out to catch her. “Swik!” went the webbing and, in the saddest sound-effect in comic book history, “Snap!” went Gwen Stacy’s neck. She was the first major ongoing character to be killed in the course of a story.

In the days before fan-based Internet websites trumpeted upcoming storylines, Gwen’s death was a complete surprise; a shocker, in fact. Comic book writer Mark Waid recalls: “I was ten years old at the time and I thought of Gwen Stacy as my girlfriend. I remember where I was reading that comic and I remember walking around in a daze for the rest of the day because in comics, characters didn’t die. Gwen Stacy was the one good thing in Spider-Man’s life. And Gerry Conway yanked that away from him. That was devastating.” Conway, who professed to be far more intrigued with the character of Mary Jane as a possible paramour for Spider-Man, viewed Gwen’s death as a narrative choice with the greatest dramatic effect. “Up to that point, in a comic book, a character like Superman will catch Lois Lane, and she’s safe. You always had the sense that at the end of the day, everything was going to be made right. But, when Gwen Stacy died, there was no rational reason for it other than the tragedy of life.”

For Conway, Gwen’s death was also a metaphor of the zeitgeist of the early 1970s. “That era was all about good people trying to do the right thing and messing up horribly. Spider-Man, trying to save the woman he loves, ends up killing her. We were in the Viet Nam War; the soldiers who went over didn’t go over there to be bad guys. They went over there to try to do the right thing. In the process, they did terrible things. And that’s tragic. There was a sense that the world was not a safe and nice place and comics hadn’t really reflected that. But after the death of Gwen Stacy, comics started to reflect the real world.”

The three panels from The Amazing Spider-Man #121 (June 1973) when comic books lost their innocence; art by Gil Kane.

The shadow of the real world conflict would extend further into the Spider-Man title in the form of a violent Vietnam vet named Frank Castle. It’s worth remembering that not only did the Marvel Universe revolve around New York City, but, in the early 1970s, all of the young writing talent was living there as well. During previous generations, comic book writers and artists tended to wear ties and carry briefcases and commute into town from the suburbs of Scarsdale or Mineola, but now the talent was facing the same problems as thousands of hardened New Yorkers—and those problems were plentiful. In January 1974, the New York Times did a survey of its citizens: 63 percent of residents said that crime was their number-one concern; 41 percent said they would never set foot in Times Square; and two out of five New Yorkers expressed no confidence that a captured criminal would ever be sent to jail. Throughout the 1970s, close to two thousand people were murdered each year in New York City alone. Clearly, in the minds of some people, something had to be done.

The idea of a comic book vigilante who would take the law into his own hands was nothing new in the Western books of the 1950s, but a costumed character with such a ruthless philosophy would seem to contradict the do-gooder ethics of the superhero universe. The Punisher made his first appearance at the beginning of 1974, in the pages of The Amazing Spider-Man #129, with a February cover date, the same month as the New York Times released its poll of the city’s intimidated citizens. It was a little more than a year after Gwen Stacy’s death. “Gwen Stacy set the stage and the Punisher walked onto it,” said his creator, Gerry Conway. “Spider-Man as the good superhero fails to save the innocent girl. Well, the Punisher comes along and he’s the guy who is not going to fail because he is not going to play by society’s rules. He’s not going to wrap the villain up in webbing and put him on a ledge for the cops to come: he is going to eliminate the villain.”

LEFT: Marvel Preview #2, 1975. RIGHT: Charles Bronson was his vigilante inspiration in the 1974 film Death Wish.

Although his character was originally intended as a one-shot, the Punisher character provided a full magazine of narrative artillery. A hired assassin with a death’s-head emblem on his chest, the Punisher is manipulated by another villain to “take out” Spider-Man. His weapons include a lethal AK-47 and the kind of terse humorless threats mastered by Clint Eastwood in his 1971 film Dirty Harry. “I’m an expert at many things, murderer,” he tells Spider-Man, who blames him for, among other crimes, the death of Gwen Stacy. “Your kind of scum has ruled this country too long, punk—and I’m out to put a stop to it—ANY WAY I CAN!” With a fearsome costume (although the white boots seemed both effete and impractical for someone so devoted to carnage) and a mien that resembled Robert Mitchum after several years of basic training, the Punisher immediately caught on with readers; his implacability mirrored their own frustrations as well as the wish fulfillment of the times.

After his debut in The Amazing Spider-Man #129, the Punisher became popular enough to shoot ’em up in his own black-and-white feature only months after his debut.

The Punisher’s path had been trod before in fiction and in the movies. Conway consciously modeled him on a men’s “action adventure” character, the Executioner, a former Green Beret-turned-mercenary in a series of popular novels begun by Don Pendleton in 1969. The Executioner inspired a plethora of other paperback vigilantes and mercenaries—the Liquidator, the Death Merchant, the Destroyer—usually former battlefield vets or CIA operatives who decide to fight crime on their own merciless terms. It was a sub-genre that reached its apotheosis in 1974, when Brian Garfield’s Death Wish was made into a frighteningly successful pro-vigilante film starring Charles Bronson.

“[The Punisher] also comes out of incredible complexity and craziness of the Nixonian period—a social breakdown of all the rules and regulations that we had all thought we were living by,” said Conway. “The Punisher has a simple answer to all this: ‘I’ll take care of it. You know I will do it, there’s not going to be anybody between me and justice.’ ” The character became a 1970s version of the Mike Hammer detective character that Mickey Spillane created out of the disillusioned veterans of World War II. More than a year after his debut, the Punisher was given his own backstory by Conway in another Marvel magazine, an origin that reflects his pulp antecedents. Frank Castle is a former Marine, a Vietnam vet who takes his family on a picnic in Central Park (where, the 1974 New York Times poll reported, 38 percent of New Yorkers would not dare to visit alone). His wife and daughter inadvertently witness a mob hit and are rubbed out by the Mafia. Bereft with grief, Castle takes on the Mafia with a vengeance. By the mid 1980s, the Punisher was given his own title and soon became the poster boy for the “grim-and-gritty” vigilante; that title eventually begat other, more violent titles such as Punisher War Journal and PunisherMAX (with maximum violence), as well as backstories that framed his formative years in Viet Nam. Frank Castle evolved into one of Marvel’s most popular characters, even though it seemed that, at the rate he was mowing down organized criminals, the Human Resources office at the Mafia would have to be working overtime.

The Punisher leapt beyond the confines of the Spider-Man book to become both a reflection and refraction of his times. As Conway states, “A character like the Punisher or like Batman is open to interpretation. The Punisher became, in effect, a wonderful Rorschach test for writers and artists over the last thirty years to comment on society, to comment on violence, to comment on the heroic ideal. He comes out of that twisted view of the Viet Nam vet—the defender of society who is also a danger to society.”

The death of Supergirl was a cosmos- (and continuity-) shattering event: Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 (October 1985).

t Marvel Comics, they were called “True Believers”—the fans that could be counted on to follow as many adventures as possible and buy as many comic books per month as their allowance would, well, allow.

t Marvel Comics, they were called “True Believers”—the fans that could be counted on to follow as many adventures as possible and buy as many comic books per month as their allowance would, well, allow.

As the Reagan Administration began, it was very clear that True Believers were no longer just kids asking their parents for a quarter to buy the latest issue of Howard the Duck—they also included adults with discretion and discretionary incomes. They also constituted a large and increasingly powerful voting bloc called “fandom.”

Fandom had existed earlier than Superman; it was Jerry Siegel who mimeographed his own fanzine back in Glenville High (among his groupies were Julie Schwartz, who would later become a powerful and influential editor at DC Comics). Comic book fans still communicated through letters and home-made magazines (such as Alter-Ego, begun in 1961 by Jerry Bails, and edited by the pre-professional Roy Thomas), but they rarely had an opportunity to meet, swap comics, and argue about which Spider-Man artist was better. That changed in the late 1960s, when a high-school English teacher, Phil Seuling, initiated the New York Comic Art Convention, which opened up a hotel ballroom every year (and the second Sunday of every month for smaller gatherings) for a series of panels, costume parades, and extensive buying and trading of comic books, magazines, toys, and other ephemera. This was a parallel event to the ongoing interest in science fiction—soon, Star Trek conventions were popping up across the country. By the time Marvel Comics sponsored their own three-day convention in 1975, the comic book convention had gone from a pastime to an institution. In the post-Internet days (and beyond), the comic book convention—in New York or Chicago or San Diego or your local Holiday Inn—has become an essential aspect of both fandom and the industry.

A Jim Steranko promotion for one of the first comic book conventions, 1968.

Fans were also seminal in changing the dynamic of purchasing comic books. About the same time as conventions were becoming touchstones of fandom, specialty comic book stores started opening across the country. Initially a by-product of the “head shops” that sold incense, records, and drug paraphernalia, comic book shops emerged as the major hubs of the industry. Shop owners were usually fans themselves—rather than, say, a cranky candy store owner who was always yelling at kids for reading instead of buying—and they didn’t mind if customers read the comic books; they were doing so themselves. The owners also knew what readers wanted. Normally, distributors sent out a wide variety of comic books to candy stores or stationery shops, which usually returned about half their stock each month as unsold comic books, often with their covers ripped so they could not be resold. But comic book store owners could predict in advance which titles would be popular, especially if a premiere issue of some character was coming down the pike. Savvy fans-turned-businessmen, such as Phil Seuling, realized they could cut out the middleman, remove the distributors altogether, and sell comic books directly to readers.

Editor/writer Roy Thomas brought back some neglected heroes from Timely’s Golden Age for the conclusion of the Skrull vs. Kree saga (March 1972).

This sensible bartering system caught on quickly; by the 1980s, the direct sales market was responsible for more than 75 percent of all comic book sales; this was a win-win, as the publishers could print runs with more precision, and the direct sales dealers got their comics at a preferential rate.

Still, sales of most comic books in the late 1970s and early 1980s were, with some exception, a fraction of what they had been in the mid 1960s—not to mention compared to sales in the 1940s. Special events soon became a clever, if overused, method of ginning up sales. Creating suspense for an upcoming premiere issue usually worked for a while—sales for Howard the Duck #1 were huge, but the title quacked up after a few years. The idea of an ongoing series that would hook readers sequentially began, almost by accident, when Roy Thomas created the nine-issue “Kree-Skrull War” for The Avengers in 1971-72. The series involved many of Marvel’s most popular characters (as well as some cameos from the 1940s canon) and, when Neal Adams illustrated several of the issues, it was a high-water mark for Marvel in the 1970s.

In 1982, Marvel returned to the idea of an everybody-on-board limited mini-series with Contest of Champions, but that was just a dress rehearsal for Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars, a twelve-issue mini-series that stretched from May 1984 to April 1985. Secret Wars began as a phone call from the leading toy manufacturer, Mattel, to Jim Shooter, then editor-in-chief at Marvel Comics. Mattel wanted to launch a series of licensed Marvel action figures, but would only do so if there were some sort of marketing peg on which to hang the whole enterprise. Both companies sorted out which characters would jointly appeal to the comic book/toy market and launched the year-long series in the largest cross-promotion event in comic book history up to that point. It was also a huge hit at the cash register—it was the best-selling Marvel title of its time, although the series sold far more comic books than action figures. The series even had an ongoing legacy in the Marvel Universe, including the introduction of a new, sleek, black costume for Spider-Man (later revealed to be an amorphous alien parasite called a Symbiote, whatever that is).

If you weren’t completely exhausted by Secret Wars, you could plunge directly into DC Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths, a twelve-issue “maxi-series” that debuted the same month that Marvel’s epic concluded. Crisis on Infinite Earths was the most ambitious series to appear up to that time, and remains one of the most seminal series in the history of comic books. The DC Comics mythology—spread out over fifty years, several galaxies, and many fictional cities—had become complex, contradictory, and clogged. Sometimes, it was so arcane (there had been different competing “Earths” since the Golden-Age Flash met the Silver-Age Flash in 1961), that it was inhibiting new buyers from parting with their dollars.

Long the brainchild of Marv Wolfman, Crisis came about as both an epic housecleaning fantasy and a way to make DC Comics relevant again. “If you were a fan who read Marvel, or a professional who was coming from Marvel, you knew characters had to change—or at least have the perception of change,” said Wolfman. “And DC wasn’t doing that. With Crisis on Infinite Earths, we’d actually make a major change that comics had never seen. We would call so much attention to DC that it couldn’t be ignored and the readers would be intrigued.”

Working with the precise, encyclopedic, detailed vision of artist George Pérez, Wolfman contrived a way to bring every DC character—hero, villain, or undecided—into his epic, which allowed him to conflate the company’s various “Earths” into one manageable universe. Such an Homeric task was bound to have some repercussions; indeed, several of them influenced DC Comics for decades (and still have the power to enflame debates at panels at comic book conventions). Realizing that the profundity of Superman’s mythos rested on his status as sole survivor of a dying planet, Wolfman and Co. killed off his Kryptonian cousin, Supergirl, and bumped off the Silver-Age Flash for good measure (however, he was soon replaced by his protégé, Kid Flash).

The Flash makes a final sacrifice for humanity and for continuity: Crisis on Infinite Earths #8 (November 1985, art by George Perez).

A rabid fan of comics since the 1950s, Wolfman saw Crisis as a tipping point, a way of admitting that the fanbase had gotten older and yet somehow needed to make room for another generation. An epilogue in the series had a deranged villain called the Psycho-Pirate expound a metaphysical view on the whole landscape of both comic books and their readers:

You see, I like to remember the past because those were better times than now. I mean, I’d rather live in the past than today, wouldn’t you? I mean nothing’s ever certain anymore. Nothing’s ever predictable like it used to be. These days you just never know who’s going to die and who’s going to live.

The two major company “crossover” series in the mid 1980s were a harbinger of things to come. Annual events were now plotted by both DC and Marvel with almost numbing regularity. Sometimes the mini-series were routine and uninspired, sometimes they were astonishing and revolutionary. Two things were sure: nothing would be predictable like it used to be; and there were now plenty of citizens of “Fandom” ready—nay, eager—to argue about the consequences.

Spider-Man swings right up and meets the Mets: with other costumed crazies at Shea Stadium, June 5, 1987.

pider-Man was conceived in 1962 as the ultimate teenager; but, in the real world, teenagers eventually grow up. And on June 5, 1987, so did Spidey. As the 1980s began, Spider-Man had supplanted Superman as America’s most popular comic book hero. He was holding down three separate comic book titles a month; he had just concluded a prime-time series and was segueing into a new animated series; and he was emblazoned on innumerable lunch boxes, toothbrushes, board games, sheets, and towels. In addition, since 1977, he had been featured in one of the few daily action comic strips to succeed in newspapers since World War II. Written by Stan Lee and illustrated by Larry Lieber, the syndicated The Amazing Spider-Man strip harkened back to the Holy Grail that Siegel and Shuster had sought for Superman in 1938.

pider-Man was conceived in 1962 as the ultimate teenager; but, in the real world, teenagers eventually grow up. And on June 5, 1987, so did Spidey. As the 1980s began, Spider-Man had supplanted Superman as America’s most popular comic book hero. He was holding down three separate comic book titles a month; he had just concluded a prime-time series and was segueing into a new animated series; and he was emblazoned on innumerable lunch boxes, toothbrushes, board games, sheets, and towels. In addition, since 1977, he had been featured in one of the few daily action comic strips to succeed in newspapers since World War II. Written by Stan Lee and illustrated by Larry Lieber, the syndicated The Amazing Spider-Man strip harkened back to the Holy Grail that Siegel and Shuster had sought for Superman in 1938.

A Marvel merchandise brochure adds a new character: Spider-Woman (1978). BOTTOM: Live from New York: one of the strangest Spider-Man team-ups ever (Marvel Team-Up, 1978).

Lee had a ball grabbing back the reins of the web-slinger, but as the 1980s galloped along, he decided to marry off Peter Parker to his longtime on-again, off-again girlfriend, Mary Jane Watson. “I mean, Peter Parker had been dating Mary Jane for years, he was in love with her, well, what’s the next logical development?” Lee sensibly queried. There was a big glitch, however—the strip was published separately from Marvel Comics by King Features Syndicate and there was no expectation of continuity among the strip and the various comics. Marvel’s current editorial staff had no plans to do anything like marrying off Peter Parker.

The Marvel editorial staff moved quickly: the countdown was to a June wedding and it was imperative that the strip and comic books intersected at the same time. (Writer David Michelinie made a quick pivot in continuity to have Peter Parker propose to Mary Jane at the end of The Amazing Spider-Man #290, although she took a couple of issues to accept his offer.) In a move that was a press agent’s dream—and contrived to promote the wedding issue (The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21) that would hit the stands the following Tuesday—the nuptials were dramatized at home plate at Shea Stadium, where two models would impersonate Spider-Man and M.J. in front of a crowd of 45,000 baseball fans waiting for the Mets to play the Pittsburgh Pirates.

M.J.’s dress was created by one of the hottest fashion designers in the actual business: Willi Smith, who had stunned the fashion world with his suits for the groom’s party at Caroline Kennedy’s wedding in 1983. Sadly, Smith, whose contemporary style was perfect for a comic book heroine—“I don’t design clothes for the Queen, but for the people who wave at her as she goes by,” he once said—had died of complications from AIDS weeks before the ceremony. (Lee would devote precious comic strip space to memorialize Smith’s contribution.)

Marvel annuals were always good venues for major events: the Spider-Man/Mary Jane wedding topped them all.

Still, the event was highly anticipated. The New York Times Style section, which covered the wedding, quoted Mary Jane as saying that the groom was nervous: “He’s been pacing the ceiling for weeks.” Attending the wedding were Captain America, Dr. Doom, Iceman, and the Incredible Hulk; in a felicitous bit of casting, the officiant was none other than Stan Lee: “I performed the marriage [ceremony]. It had to be legal, so, it had to be someone like me who had the authority to marry them. And all I could think of was—they had the ceremony before the game—the zillions of fans in the stands are probably thinking, ‘When is the game gonna start?’ ”

The public-relations aspect of the Spider-Man/Mary Jane wedding was a spectacular success, picked up by major media outlets across the country, and the special issue featuring the wedding was a huge best-seller. In the real world of comics, however, there was a problem of unintended consequences. Back in 1961, Stan Lee and his collaborators had changed the whole game of comic book superheroes based on the assumption that they lived in a world that resembled ours, they had problems like ours, they could be us.

Except they weren’t. They were highly profitable commercial entities, too, which had developed surprisingly long lives in the marketplace. Fans had spent years following these superheroes and their supporting characters, identifying with them, growing older with them. And suddenly, the most revolutionary aspect of Stan Lee’s innovation’that superheroes could appeal for the first time to older readers—became problematic for the industry that made fortunes off them. Artist Joe Quesada, who would inherit Stan’s old post as editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics in 2000, framed what the Thing would call the whole “revoltin’ development”:

If you had been reading Spider-Man for ten years, fifteen years, this was a logical place for the character to go because you yourself had probably either gotten married or were ready for marriage. So the character was aging along with you. But, really, at the end of the day, when you have a character that has to be there for the next wave of readers, at what point do you stop? Does Peter Parker then have kids? Does he then grow old and become a grandfather? Does he then die? We really couldn’t go there.

It was a dilemma that the comic book industry had made for itself out of its success, an unintended consequence of creating, cultivating, and maintaining loyal readers. For the next generation of superhero writers and artists, the choice was inevitable: they had to go there. And the “there” was a rarely considered, infrequently traveled territory in the world of “amazing fantasy”: reality.

The magic moment: The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987, art by John Romita, Jr.).