Wolverine bares his teeth in Uncanny X-Men #132 (April 1980), signaling the dawn of the grim-and-gritty age.

ince the late days of the Depression, the comic book industry had been comprised of several immutable constants: the firms had been run by professionals who had their roots in the publishing and distribution business; the companies were based in New York; they were relatively small in nature, staffed largely by middle-aged adults who usually commuted at night to homes in the tri-state area, where they sat in armchairs and read literature other than comic books.

ince the late days of the Depression, the comic book industry had been comprised of several immutable constants: the firms had been run by professionals who had their roots in the publishing and distribution business; the companies were based in New York; they were relatively small in nature, staffed largely by middle-aged adults who usually commuted at night to homes in the tri-state area, where they sat in armchairs and read literature other than comic books.

That would all begin to change in the early 1970s, when a new generation of comic book writers and artists entered the field, former fans who had grown up with the medium and were eager to intertwine the adventures of their favorite superheroes (or at least the superheroes they were assigned by their middle-aged editors) with the issues of their day: Denny O’Neil, Neal Adams, Gerry Conway, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman. “For a long time,” said Conway, “we’d say that comics were going to be dead in ten years. By the late ’70s, enough of us probably believed that that we started saying, well, maybe we better find other ways to make a living.” Some of the ’70s superstars (Conway, Wolfman) would follow Stan Lee’s lead (once again) when he moved to Los Angeles in 1981, in his case to pursue new venues on behalf of Marvel in film and television. O’Neil and Wein would stay in comics, but expand their acumen to edit the work of newer, edgier talents.

Michael Keaton as Batman (1989) ushers in the bat-conquest of the media age.

A roundup of artists and writers who either went west or expanded their horizons in the late 1970s (from top): Denny O’Neil, Jack Kirby and Neal Adams, Marv Wolfman and Len Wein, Gerry Conway.

These creators left the field to the next generation—writers and artists who had been inspired by their attempts to make comic books more relevant. A surprisingly large number of the next generation’s most spectacular talents came from the United Kingdom, largely from the northern part of England. They included Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Dave Gibbons, and Mark Millar, young creators who expanded into other non–comic book areas such as punk music, novels, graphic design, and the occasional dabbling in occultism.

The diverse and non-mainstream backgrounds of these U.K. artists helped to transition the increasingly dull comics of the mid 1980s and 1990s into frequently surprising departures from the norm. “It was time for us to come along. The American comic had become focused on this scorecard mentality,” said Morrison. “Is the Thing stronger than the Hulk? It was a very strange time. It became almost like stamp collecting.”

TOP: Three influential comic book creators Alan Moore (top), Frank Miller (left), and Grant Morrison (right).

BOTTOM: And their epic contributions: Ronin (1983); Arkham Asylum (1989); V for Vendetta (1988).

As different as Morrison’s generation of creators was from their predecessors, the biggest change may have been in the consumer base. As comic books moved through their sixth decade, it became clear that many longtime readers weren’t going anywhere—they were reading comics into their thirties and forties and they didn’t want to read the same old stories where the Flash foils the Mirror Master from robbing a bank. They wanted growth and development, just as they themselves were growing and developing. “So you have this conflict between the desire of an ongoing readership and the nature of these superhero characters which is static,” said Conway.

The maturing audience encouraged the new brand of creators to venture into more complex territory—much of it darker than the usual superhero fare, playing into the stereotype of the “grim-and-gritty” era. The comic book publishers, realizing that their audience was diversifying, created discrete imprints for this mature work. Vertigo Comics, an imprint marketed as “suggested for mature readers” and including well-received titles such as Gaiman’s psychological fantasy series, The Sandman and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, found a home at DC Comics. Epic Comics was Marvel Comics’ repository for creator-oriented titles that explored mature storylines outside of the Marvel Universe, often without the approval of the Comics Code (Marvel followed Epic with another mature-themed imprint, MAX, in 2001). A new venue emerged for expanded, more complicated superhero-oriented tales: the graphic novel.

There had always been attempts at expanding comic book storytelling into longer, non-serial, self-contained forms—the burst of sword-and-sorcery one-offs in the early 1970s, for example—but publishers realized there was a new market for one-shot tales, as long as the characters were familiar and the printing of the books (often hardbound and softbound, concurrently) exhibited the durability of a novel, rather than the transience of a pulp comic book. One of the most successful of these early attempts was Grant Morrison and painter/illustrator Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989), a format-shattering tale of Batman encountering a dark night in Gotham City’s most famous (and not terribly competent) madhouse.

The trade paperback was a “win-win,” giving publishers another venue in which to print (and reprint and re-reprint) popular stories, while allowing literary critics to take the non-disposable publications seriously. Perhaps no other publication benefitted more than Moore’s Watchmen, which was placed on Time magazine’s list of “The Hundred Greatest Novels Ever” in 2005—the only comic book narrative to earn that honor—and eventually moved millions of copies. But neither Watchmen nor The Dark Knight Returns nor a host of other “graphic novels” were actually graphic novels; they were paperback (or hardcover) compilations of material that had appeared previously in serial comic books, a distinction that was largely lost. Alan Moore personally detested the lack of clarity: “The problem is that ‘graphic novel’ just came to mean ‘expensive comic book’ and so … [DC or Marvel would] stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel.”

Be that as it may, there were vast new marketing possibilities for ancillary material. Some of this was because both DC and Marvel would be folded into larger and larger conglomerates as the 20th century drew to a close. The DC stable of characters benefitted from a well-orchestrated corporate transition when Warner Communications—which had already been instrumental in bringing Superman to the big screen through their film studio connections—merged into the mammoth corporation of Time Warner in 1990.

Since the success of the Superman film in 1978, there had been a slow, but relentless, drive to put Batman back on the screen, and Warner Bros. was the obvious studio to make it happen. One of the early producers on the project, Michael Uslan, thought it was time to break through the campy veneer that had kept Batman from the larger public he deserved. The Miller Dark Knight saga gave the embryonic project the credibility it needed to move forward, and in 1988 Warner Bros. hired idiosyncratic filmmaker Tim Burton to bring Batman to a new generation. According to writer Grant Morrison:

Tim Burton related Batman to things that were happening then’the fetish underground, the transgressive elements, the Gothic elements which were coming out of music as well. There was a real heavy punk element to the whole thing and Batman very quickly adapts to that; he was a black leather figure in a cave.

The rising influence of Batman conferred a new spotlight on his arch-nemesis, the Joker. Brian Bolland’s deranged conception for The Killing Joke (1988) inspired Jack Nicholson’s portrayal in Batman (1989).

Burton was not a comic book fan—he claimed he never knew how to follow the way the panels moved on a page—but he was inspired by another progeny of the Dark Knight saga, a one-off graphic novel from 1988 called Batman: The Killing Joke. A terrifying story of the Joker at his most disturbingly deranged, it was illustrated by Brian Bolland and written by Alan Moore. Moore and Bolland’s Joker would provide the inspiration for Jack Nicholson’s brilliant portrayal in the Burton film. The final result, Batman, released as a tentpole blockbuster in summer 1989, racked up an astounding $150,000,000 in its initial domestic release, and led to three sequels (of variable quality). Through their association with Warner Bros., DC Comics proved they could deliver first-rate films based on their signature characters.

Marvel, on the other hand, seemed to have nothing but bad luck; its parent organization was bought by Revlon founder and stock market whiz Ronald Perelman in 1989; eventually, due to some bad moves with affiliated companies, the complex corporate entity that owned Marvel Comics and its characters filed for bankruptcy. During this time, Marvel kept trying to expand its reach in various marketing fields such as action figures and video games, but the Holy Grail of a blockbuster film or two had eluded Marvel completely, despite Stan Lee’s best efforts as ambassador-with-portfolio in Hollywood. Marvel sold the rights to some of its most famous characters for bargain-basement prices to independent studios on the lowest end of the food chain. Despite a much-trumpeted deal in 1990 with filmmaker James Cameron to bring Spider-Man to the screen (which never happened), Marvel was stuck with dogs so cheaply made (The Punisher, Captain America) that they barely made it onto videocassettes. Most embarrassing was the 1994 version of The Fantastic Four, which was made (for a rumored $1.5 million) only to hold onto the screen rights: the final dismal result was never meant for commercial distribution.

No supervillain could have dropped as many bombs as Marvel Comics did in their movie ventures in the early 1990s. Captain America (1991) went straight to video, as did The Fantastic Four (1994).

Marvel would eventually find its groove in Hollywood by the 21st century, but the late 1980s represented a massive sea-change in the comic book business, a Super-genie that would be impossible to put back into a bottle—even a bottle as large as the one that holds the city of Kandor. For Gerry Conway, the corporate evolution of the industry was the biggest game-changer of all:

While we loved what we were doing in the ’70s, I don’t believe we thought that it mattered and certainly our publishers didn’t think that it mattered. If a particular issue didn’t do well, that was fine, there was next month. We didn’t have this sense that careers revolved around choices that you make for this particular character a year in advance. I think that’s a creative soul-killer for the business.

The first meeting of the Crimebusters—an unlikely alliance from Watchmen #2 (1986); text by Alan Moore, art by Dave Gibbons.

Torch-passing: Alan Moore and Jack Kirby at a 1985 comic book convention. RIGHT: DC’s Swamp Thing deepened its roots under Moore (Swamp Thing #47, 1986).

he summer of 1986 may well have been the last anxiety-free period in superhero history. The final installment of The Dark Knight Returns would hit the stands in June, and in September the first installment of the twelve-issue limited series Watchmen—written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons—would make its debut. Taken together, the two series would irrevocably change the conventional wisdom about superheroes. “I like to joke that when it comes to superheroes,” said Frank Miller, “Alan Moore provided the autopsy and I provided the brass-band funeral.”

he summer of 1986 may well have been the last anxiety-free period in superhero history. The final installment of The Dark Knight Returns would hit the stands in June, and in September the first installment of the twelve-issue limited series Watchmen—written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons—would make its debut. Taken together, the two series would irrevocably change the conventional wisdom about superheroes. “I like to joke that when it comes to superheroes,” said Frank Miller, “Alan Moore provided the autopsy and I provided the brass-band funeral.”

Moore was an unconventional writer, even by comic book standards. Born in 1956 in the small English city of Northampton, where he lives to this day, Moore, by his own admission, hadn’t been to a barbershop since he was a teenager. A Merlin-like figure who embraces necromancy and derides capitalism with equal fervor, Moore began his career in British comics, where his work attracted the attention of Len Wein, then an editor at DC. He engaged Moore—who continued to bang stories out at his kitchen table in Northampton’to write unpredictable spins on characters as varied as Swamp Thing and Superman. Some readers (and editors) were put off by his perspective—“I didn’t realize that incest and necrophilia were still frowned on socially over here,” he said—but fans sat up and took notice.

Early in 1985, Moore had a notion about an extended story that would be ignited by the death of a superhero and its reverberations through his former fellow teammates. It was important to Moore that the team be composed of heroes who had some real history behind them; luckily for him, DC Comics had recently acquired the Charlton line, which had some success with a few B-level characters in the 1960s: Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, and Steve Ditko’s trenchcoated mystery man, the Question. “That’d be a good way to start a comic book: have a famous superhero found dead,” said Moore. “As the mystery unraveled, we would be led deeper and deeper into the real heart of this superhero’s world, and show a reality that was very different to the general public image of the superhero.” Although intrigued by the possibilities of using the Charlton characters, DC editor Dick Giordano soon realized that Moore’s epic vision would render these potentially lucrative properties unusable or extinct; it was politely suggested that Moore create them out of his own considerable imagination.

With Curt Swan’s help, Moore bid farewell to a traditional Superman (Action Comics #583, 1986); Charlton Comics’ staple of second-rate heroes from 1967 inspired the characters in Watchmen—Captain Atom became Dr. Manhattan.

Working with the precise and affectionate imagery of his fellow countryman Dave Gibbons, Moore created a credible set of 1940s heroes, called the Minutemen, and their figurative and literal descendants, the Crimebusters. (Although the series would be called Watchmen, no group of superheroes calling themselves the “Watchmen” ever appear.) They include Nite Owl, a nocturnal paraphernalia-riddled crimefighter redolent of Batman; and Rorschach, a trenchcoated mystery man with an ever-shifting inkblot of a face. Any readers who noticed a generational shift from the eager-beavers of the 1940s (who embodied the values of the DC characters) and the querulous do-gooders of the atomic age (Marvel Comics types) had been paying attention. What united the nearly dozen disparate characters in Watchmen was Moore’s basic contempt for the unvarnished enthusiasm in superhero comics: “Actually, a person dressing in a mask and going around beating up criminals is a vigilante psychopath. What would that Batman-type, driven, vengeance-fueled vigilante be like in the real world? And the short answer is: a nutcase.”

The complex twelve-issue story arc of Watchmen played out in a parallel universe to our own. In it, Richard Nixon has remained president of the United States into the 1980s and America has built a carapace of world domination, aided largely by the benign complicity of Dr. Manhattan, an atomically enhanced scientist of extraordinary powers who is, for the most part, thankfully on our side. Still, the United States and the U.S.S.R. are tied in a Gordian Knot of mutual deterrence. The death of a mercenary superhero named the Comedian—an ironical, rather than amusing, bully—sets off a chain reaction of events that involves several generations of superheroes dating back to the late 1930s. Moore’s narrative, which segues in and out of time, space, and medium, comes to a climax when a lapsed superhero, hyper-brilliant megalomaniac and businessman Adrian Veidt (once known as the superhero Ozymandias), decides on his own to sever the Gordian Knot of global conflict (already coming to a head in Afghanistan) by transporting an immense mutated intelligence form to New York City. The alien form essentially explodes and kills more than three million people, providing an uneasy tabula rasa on which to build a new, coherent society.

The sociopathic Rorschach and the ambivalent Nite Owl were wary teammates as the Crimebusters.

Folded into the epic were the multiple levels of Moore’s Baroque (and Mannerist) leanings’ classical allusions, song lyrics, parallel texts, spurious source material—mixed in with a love for popular culture and superhero lore (a major malefactor asserts that he’s smarter than “a Republic serial villain”—a reference to the cheesy 1940s serial adventures of Captain Marvel and Co.). Gibbons’ highly controlled, ordered, rectilinear panel layout not only “quoted” previous layouts from the early 1960s, but provided a contained prism through which the madness of Moore’s method could be discerned, without driving the reader completely around the bend. Still, Watchmen was a vivid tapestry that benefited from multiple readings: “This is what I’ve been trying to explain to these stupid bastards for the past twenty years,” wrote Moore. “[My work] was designed to exploit all the things that comic books can do and that no other medium can. I wanted to show off just what the possibilities of the comic book medium were.”

The most effective and influential reading of Watchmen came with its gloss on the idea of fantastical characters confronting the quotidian existence of the real world: if your superhuman boyfriend teleports you through time and space, you just might get sick to your stomach and vomit; if you maintain a secret crime-cave, it might just require a lot of expensive upkeep and cleaning fees; if you gained your astonishing powers from potent radiation, you might just give your sidekick cancer. And, of course, if you were the mightiest being in the world, you might just want to control it. In a sequence of panels where an older, paunchier version of Nite Owl gives the retired superheroine Silk Spectre (whom he is awkwardly trying to seduce) a tour of his secret crime-cave, he admits:

The essential argument of Watchmen: superheroes are very different from you and me—and not necessarily in a good way. Nite Owl and Silk Spectre in Watchmen #7.

“Here is the primary difference between the before-and-after Watchmen scenario,” said writer J. Michael Straczynski. “Before Watchmen, the primary threats or darkness in comic books was about some supervillain’s complicated plot to seize all the gold in the world. What Watchmen did was bring in the larger social elements. It spoke of the darkness inside of us, not just the external threats, and that was something that galvanized the industry.” When the series was ultimately completed and eventually published in paperback, Watchmen became the darling of literary critics, a pop-culture manifesto that could be taken seriously. In a 2005 review in the New York Times, Dave Itzkoff wrote, “If we imbue our champions with the weaknesses of ordinary mortals, Moore asks, and confine them to a cosmos where good and evil are subjective notions and right never triumphs over wrong, what’s the point of having heroes at all?”

Watchmen became one of the most imitated comic books of all time; one trope, about a government commission that banned superheroes, would pop up again in nearly a dozen different storylines in various comics over the years. And the book’s mature themes, stark visuals, and undercurrent of nihilistic violence would feed the undercurrent of superhero comic books far into the 21st century. According to Len Wein, “Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were both very violent books. They were meant to be exceptions to the rule. They weren’t intended to be a blueprint for the industry to follow, they were intended to be something to show you here’s what could have happened—let’s not go do that. But they were hugely successful and so everybody started to do those books.”

As much as Moore borrowed from the real world, the real world also tapped into Watchmen. In 1987, the Tower Commission Report, which investigated the Reagan Administration’s questionable dealings in supplying arms to foreign radical forces, came out with a condemnation of the administration’s “lax attitude” to international law: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes” ran the epigraph of the report—“Who watches the Watchmen?,” the same slogan that runs through the Moore/Gibbons saga.

Given the immense influence and cultural imprimatur of Watchmen, perhaps Frank Miller’s assessment of Alan Moore’s occupational status was incorrect. Perhaps Moore was not the coroner of the superhero world at all, but rather its psychotherapist: a psychotherapist who snuck away from his patients during the last two weeks in August, and hightailed it to a small city in England instead, leaving his poor, pathologically damaged superclients to fend for themselves.

LEFT: In the climax of the Watchmen saga (#12), Dr. Manhattan confronts the deluded Adrian Veidt, who is about to unleash cataclysm on New York City. RIGHT: Dr. Manhattan towers over his adversaries (and breaks up Dave Gibbons’ controlled panel arrangement) in Watchmen #4.

A man out sitting in his field: Todd McFarlane riffles through his hits.

t’s probably not coincidental that “I” is the first letter in “Image Comics.”

t’s probably not coincidental that “I” is the first letter in “Image Comics.”

When seven of the comic book industry’s most popular artists stepped away from the corporate halls of Marvel and DC to form the most successful publishing consortium outside of the Big Two since the days of Captain Marvel in the 1940s, they were asserting their independence and their personal visions. Some in the comic book industry exhumed the same snarky comment bandied about when Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D.W. Griffith broke away from the Hollywood studio system to create United Artists in 1919: “The lunatics have taken over the asylum.” Fans and older readers, however, were thrilled to have a new, independent company that had the motivation—and the talent—to bring another generation of characters to the superhero universe.

The seven founders of Image—Erik Larsen, Todd McFarlane, Mark Silvestri, Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, Jim Valentino, and Whilce Portacio—possessed powers far beyond those of mortal comic book artists; they were superhero superstars, artists who had cultivated a loyal following, with their names burnished on covers in type almost as large as the superhero logos. McFarlane’s idiosyncratic and fanciful rendition of Spider-Man produced a two-million-copy seller with Spider-Man #1 in 1990; Liefeld’s sleek, steroidal style kickstarted the four-million-copy selling X-Force #1 (featuring the previously dubbed New Mutants). In the big-stakes poker game of blockbuster comics, Jim Lee saw his colleagues and raised them in 1991—utilizing his skill for populating his panels with pulsating power—with X-Men #1, which set the record for a single title: 7.8 million copies. With such success, McFarlane, Liefeld, and Lee had everything a comic book artist could want.

Justice League of America #192 (1981) inspired a young Canadian fan to riff on his favorite android, the Red Tornado. BOTTOM: Rob Liefeld, Stan the Man, and Todd McFarlane celebrate Marvel Comics, seemingly hours before Liefeld and McFarlane would depart.

Except control. Since the days of Siegel and Shuster, publishers held almost all of the cards. Although by the 1990s artists and writers were gaining some concessions from the publishers—the return of original art, a small share of royalties, top billing, and so forth—they were still confined by the fact that the superheroes they worked on (and adored) were owned by an increasingly bureaucratic corporate structure. An artist such as McFarlane could take a character like Spider-Man into the creative and financial stratosphere, but at the end of the day, Spidey had to swing back to corporate headquarters and report to the board of directors and their investors. As Larry Marder, Image’s executive director, put it, “In the comics field you have two choices: Work on what you own. Or work on something someone else owns. Period.”

The unmatched success of Jim Lee’s X-Men #1 stretched across four variant covers (1991).

By mid 1991, Liefeld and McFarlane were feeling particularly discontent with Marvel, which was putting limitations on what they could and could not draw or publish outside the company. There had been informal conversations among the duo and other artists about forming separate imprints, perhaps overseen by Malibu Comics on the West Coast. Around Christmas 1991, Liefeld, McFarlane, and Silvestri were in New York City for a highly publicized auction of original comic book art, including their own, and realized this was the moment to come together. As McFarlane, a baseball fanatic, put it, “I was always aware that they [publishers] can rotate you one at a time. You see it in sports, you can get rid of one player, they bring in another guy and eventually the franchise is okay. But, instead of us all going away one by one and doing an independent book each, why don’t we do it together at the same place and leave on the same day? Make the impact.” The key, according to McFarlane, was to engage Jim Lee, who was considered to be the “Golden Boy” of comics, a well-liked and amiable collaborator who had none of his colleagues’ reputations as hot-heads. Like many a superteam before them, the seven artists realized that, combined, their strengths were exponentially more powerful.

They called a meeting with the senior editorial staff at Marvel—the company where they all became celebrities—and announced, as McFarlane says, “We’re leaving. We know we don’t own your characters, we’re not here to negotiate, we don’t want anything. We’re just going to tell you our reasons why we’re leaving so that you may in the future do something about it so that next week you don’t get another seven guys coming in the room saying they’re leaving.” Marvel, somewhat condescendingly, wished them the best of luck, and when the elevator opened up on the ground floor, McFarlane and Co. found themselves the co-conspirators of a new company: Image Comics. If they were daunted at the challenge of taking on two publishers who, between them, had a 95- percent market share, they didn’t show it: “We weren’t building a nuclear plant,” said McFarlane. “We were putting ink on paper. Ink on paper; we got this thing down.”

Image set up shop on the West Coast, under the initial aegis of Malibu Comics. The seven creators had their own respective studios within the publishing company, with two inviolate tenets: (1) Image would not own any creator’s work; the creator would, and (2) No Image partner would interfere—creatively or financially—with any other partner’s work. CNN’s Moneyline program got ahold of the story, and after they broadcast the news that Marvel’s seven top artists had bolted from the firm, Marvel’s stock took a considerable hit. The program compared Image’s secession to a “brain drain” and stated that the “box office” appeal of the individual artists superseded that of the Marvel characters they had been hired to illustrate. CNN predicted that readers might follow the Image artists to their new company “the way record buyers follow a rock star.”

The first Image Comics: Rob Liefeld’s Youngblood (1992); McFarlane’s Spawn #1.

Being compared to rock stars suited the Image creators just fine, as they prepared to launch their respective titles in late spring/early summer 1992. By and large, their enormous expectations were met, breaking all records for a non-DC/Marvel title: Liefeld’s debut book, Youngblood, sold 1.5 million copies; McFarlane’s Spawn broke that record within weeks by selling two million copies of the first issue. Lee’s intergalactic, internecine WildC.A.T.s series would consistently top 1 million copies per issue during the first months of its run.

Erik Larsen’s Savage Dragon #1, the beginning of a record-breaking series.

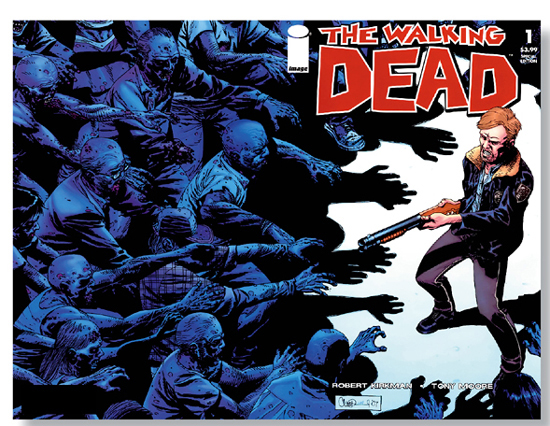

A new cover for a reprint of The Walking Dead #1, art by Charlie Adlard, from Tom Moore’s original series—the title would become Image’s most resilient series.

Inevitably, those remarkably high print runs became unsustainable. The utopian vision of Image Comics also proved difficult to sustain. Although, after its first year, Image was successful enough to break away from Malibu, some of the creators had difficulty meeting deadlines. Getting these highly anticipated books into stores became problematic, and that created an unfortunate breach of trust with loyal readers. Jim Lee would sell his Wildstorm line to DC Comics in 1998 and gradually the original seven-person partnership would splinter off. Even though the opportunity for creative freedom at Image was seductive to many outside artists, as Larry Marder put it, “They wanted the Great Power but not the Great Responsibility of owning and controlling their own intellectual property.”

For some, the story of Image Comics is a paradigm of any new business model: a company founded on independence from corporate structure had better not throw out the “baby” of a well-run machine with the “bathwater” of bureaucratic interference. For others, it was significant that the creators at Image were all artists first and writers second. As Grant Morrison put it, “They’d grown up on Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, but Stan’s comics were created from a literary standpoint. Image was artist-driven, so it was about sensation. I think American superhero fans [in the early 1990s] just wanted sensation and the generation of disaffected suburban kids who had grown up on wrestling and heavy metal and Goth were looking for something very cynical in the midst of plenty.”

Certainly the Image heroes were grittier and overstepped the usual moral principles found in mainstream superhero comics—some of the characters wouldn’t consider themselves heroes at all. The company also never bothered with any restrictions from the Comics Code Authority. Still, McFarlane’s Spawn held on, through his and various hands, for more than 200 issues and counting. Erik Larsen’s Savage Dragon, about an amiable hulking green powerhouse with a large dorsal fin on his head, proved popular enough to get its own animated series and extended publication into a second decade; Larsen set a record as having the longest uninterrupted tenure of artist and character in comic book history. Jim Valentino also made history with his urban vigilante, ShadowHawk, who began his crimefighting career after being intentionally infected with the HIV virus; ShadowHawk would be the first major comic book superhero to die from complications from AIDS.

More than twenty years after its inception, Image Comics is still hanging in there, with scores of different titles, including the zombie phenomenon The Walking Dead. Perhaps more than any one character or title, Image contributed the final breakthrough of comic book superheroes from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. As Todd McFarlane concluded:

I had a good run on Spider-Man and I had a fun time with it, but when people ask me, are you ever going to do some Marvel and DC [titles]? The answer is always the same: no. Not because I think they’re bad, but because it’s the same answer if you ask me if I’m going back to high school. I liked high school, it was fun—but, I’m not going to do it again. It’s in my past, I’m looking forward.

e had been the standard bearer of an entire industry for decades, dedicating his superhuman life and career to moving millions of copies of comic books a year. In the wake of the grim-and-gritty era, however, Superman plummeted to earth in sales, derided by certain readers as a chiseled Boy Scout, without enough psychological maladjustments to make him compelling and too downright uncomplicated to be a superstar. But, in November 1992, the Man of Steel fooled everyone. As Shakespeare says in Macbeth, nothing in his life became him like the leaving of it.

e had been the standard bearer of an entire industry for decades, dedicating his superhuman life and career to moving millions of copies of comic books a year. In the wake of the grim-and-gritty era, however, Superman plummeted to earth in sales, derided by certain readers as a chiseled Boy Scout, without enough psychological maladjustments to make him compelling and too downright uncomplicated to be a superstar. But, in November 1992, the Man of Steel fooled everyone. As Shakespeare says in Macbeth, nothing in his life became him like the leaving of it.

The commemorative logo for the “The Death of Superman!” (November 1992). INSET: Superman’s previous death: the cover of Superman #149 (1961).

Ironically, in a post–Dark Knight world, Superman’s ethical clarity made his stories murky and contrived. In 1986, Alan Moore had worked with Superman’s longtime artist Curt Swan to create a wonderfully elegiac close-parenthesis storyline entitled, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” which allowed fan favorite John Byrne to step in and reimagine Superman in The Man of Steel. The new title streamlined Superman’s background and his powers into something more credible, if that’s the word for an alien who streaks through the sky in a red cape. By 1991, Superman’s adventures were unfurled in four separate DC Comics titles, but they were weighed down by an uninspired amalgam of predictable science fiction and quotidian problems in Metropolis. Still, those four titles required an annual organizational meeting of the various editors and writers who worked on the Superman universe to sort out and conform continuity. Much like the executive producers and show runners of an ongoing television series, the creative staff at DC had an ongoing investment in the property and spent hours and hours spitballing possible storylines and conflicts over the course of a year. The character of Superman continued to be the biggest challenge, according to Mike Carlin, one of the editors: “A lot of people feel that Superman deserves to be one of the better comics out there just because he was first. At the same time, they would also rather buy Lobo [an intergalactic mercenary] or X-Men, because Superman is kind of old-fashioned in that he doesn’t like to go around killing everybody.”

That year, the editors met and decided, not unreasonably, the way to change things up was to have Clark Kent and Lois Lane get married. They presented the concept to DC’s then-publisher, Jenette Kahn. Unbeknownst to the editorial group, Kahn had been pitching an original Superman series to the various broadcast networks and had finally convinced ABC to pick up Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, which reconfigured its leading characters into a kind of screwball comedy: think of His Girl Friday, set at the Daily Planet. To have Clark and Lois married in the comic books would have subverted the initial bantering nature of the TV series; Kahn nixed the idea. Editor Louise Simonson recounts what happened next:

So what that meant was, we had to go back and start over again. And we were a little disgruntled and as [Kahn] walked out the door, [editor/artist] Jerry Ordway said what he always said, which is “Let’s just kill him.” And instead of laughing it off, this time we said, “Yeah—yeah, let’s just kill him.” And it actually seemed like a good idea. I hear today from readers who say how we did it for commercial reasons. No—we did it because we were pissed.

FROM FAR LEFT: Dean Cain and Teri Hatcher are Lois and Clark for ABC primetime television; three historic images from Superman #75, “Doomsday” (November 1992, art by Dan Jurgens and Brett Breeding).

The saga that climaxed in Superman’s demise was spread out over seven separate issues of different titles, including Justice League of America. A relentless, powerful, spiny brute, ultimately dubbed Doomsday, breaks out of a secret lab and inexorably makes his way to Metropolis, destroying everything in its path. Superman comes to the rescue, but the creature is so powerful that he beats the Man of Steel back to the streets outside the Daily Planet, where an apocalyptic slugfest renders both adversaries wasted. “You stopped him!” exclaims Lois Lane, cradling Superman in her arms. “You saved us all! Now relax until—” But it was no use. After a harrowing battle in Superman #75—rendered as 24 continuous splash pages and a climactic gatefold tableau—“a Superman died.”

After a several-month moratorium, the DC team spun out two more story arcs, a meditation on death and loss called “Funeral of a Friend”; then a more explosive storyline called “Reign of the Supermen!,” where four different costumed adventurers arrive on the scene, each claiming to be the true heir to Superman’s fame and fortune. The latter series was the most inventive of the three storylines—indeed, two of the “supermen,” Steel and Superboy (reconceived as a super-clone)—became permanent fixtures of the DC landscape. At the conclusion of that saga—nearly a year after his demise—having undergone a secret Kryptonian solar regeneration at the Fortress of Solitude, Superman returned: tan, rested, and ready (and with a longer haircut). No one who had ever read a comic book was surprised.

But the death of such a major figure in popular culture a year earlier had stunned the media and millions of casual followers who had no idea that death-and-resurrection was as common in superhero comic books as it was in the New Testament. While the editorial team was planning the original storyline in early 1992, word had leaked to the press. The DC public relations office literally had no clue how to handle the burgeoning interest; companies which had licensed Superman’s likeness for various products were complaining and the whole enterprise seemed like bad news.

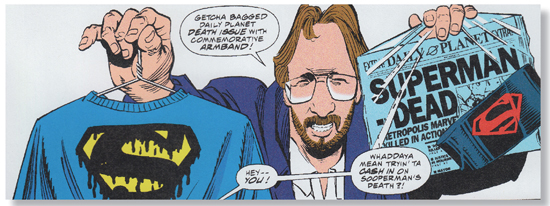

In the world of publicity, however, there is no such thing as bad news. As Superman #75 neared its release date of November 18, 1992, television news programs, newspapers, and magazines were heralding the death of Superman; it was front-page news, even in tabloids other than the Daily Planet. Aficionados of popular culture were having a field day, but that was nothing compared to an amateur investor market. DC Comics soon realized “The Death of Superman” was an unprecedented bonanza and produced several commemorative versions of the issue, particularly one sealed in a black bag that included an obituary, an armband, and other collector’s items. Alerting their dealers and comic book store owners across the country of the magnitude of the event, DC shipped out nearly three million copies.

Mike Malve owned a successful comic book store in a Phoenix mall called Atomic Comics; when he showed up for work on November 18, with boxes and boxes of Superman #75 in the back of his van, even he was shocked:

My store was by a movie theater, and that day there was a movie that opened about Martin Luther King. There was this huge line and I was like, oh wow, they must have let kids out of school to watch this movie. And then I realized no, that’s a line for my store and there were literally hundreds of people in line to get in my store. By the end of the day you were going to be sold out and so you had to put limits. So I would say look, there’s a limit of two per customer and this nice old lady was arguing with me and fighting with me: “I need twelve of these because I’ve got twelve grandchildren that need to have the Death of Superman issue!” I tell her, ma—am, I’ve got a line of a hundred people here. I want to guarantee that everybody gets one. She goes, “No, I was here earlier than them, screw them.” These are normal people talking like this.

In spring 1993, DC Comics unveiled several superpretenders to the throne, including the Man of Steel, the Last Son of Krypton, and the Man of Tomorrow. LEFT: An in-house ad for DC underscores the historical ramifications of the issue.

That once-benign old lady had a point; during the previous decade, publishers had been creating collector “events”—tying premiere issue releases to major artists, while concocting variant covers, often with gimmicks such as sealed Mylar bags, or holograms, or other collector’s items. When Todd McFarlane helmed Spider-Man #1 in 1990, the cover—of which there were several variants—unashamedly exclaimed: “1st ALL-NEW COLLECTOR’S ITEM ISSUE!” The issue sold two million copies. For veteran comics writer Marv Wolfman, the whole notion of collecting comics as a fiduciary investment is anathema to begin with: “You should read the comic, you should want the comic because you love it and you want to read them, not put them away into plastic.” Tied into these overinflated bonanzas were the occasional news stories that someone had found a copy of Action Comics #1 in their grandmother’s attic and it would sell at auction for a fortune: in 1992, Sotheby’s auctioned a pristine copy for $82,500. (In 2011, another pristine copy sold for $2.16 million.)

But even the lowliest intern at Sotheby’s could have explained a simple fact to the ferocious old lady in line at the Atomic Comics store: it’s all about supply and demand. In addition to its historical landmark status, Action Comics #1 had a print run of some 200,000 copies, of which roughly 130,000 were sold. There are only about 100 extant copies known to collectors. When three million copies of Superman #75 are sold (not including an additional three million reprints and trade paperback editions), a pertinent question remains: Who’s going to buy them now?

Store owners such as Mike Malve saw a disturbing shift in their livelihoods, which, for most comic books store owners, had begun with a pure love of the product: “People were buying [Superman collector’s editions] ten at a time and buying them for their aunts and their uncles and their nieces and nephews and their dogs, I don’t know. But nothing lasts forever. Suddenly, I started noticing we were having cases of comics that weren’t selling. We were starting to become speculators.” Chuck Rozanski, the owner of the Mile High Comics shop in Denver, said:

Frankly, I view that particular marketing event as being the greatest catastrophe to strike the world of comics since the Kefauver Senate hearings. When these new comics consumers/investors tried to sell their copies of Superman #75 for a profit a few months later, they discovered that they could only recover their purchase price if they had a first printing, [and] their bitter disillusionment did much to cause the comics investing bubble to begin bursting.

Comic art mirrors reality: a definitive moment of memorabilia from Superman: The Man of Steel #20 (1993).

The number of comics stores across America went from 8,000 at its height to roughly 2,000 by the end of the 1990s, which was a shame, because the local comic book store had provided an important social function for a burgeoning sub-section of the culture. Before the direct marketing phenomenon of the 1970s, new comic books could only be found in a candy store or supermarket; older copies could only be found by happenstance in cardboard boxes in used bookstores. Sometimes, head shops would carry posters and back issues among their psychedelic paraphernalia, but the comic book store provided one-stop shopping for the fan. Usually opening early on Wednesday mornings to accommodate the customers who craved that week’s new releases, comic book shops were endearingly deferential to their clientele. As the years wore on, the shops became emporiums for more than just comics: trade paperbacks, games, action figures, collectible statues, trading cards, toys, buttons, DVDs, and so on—most of which were produced in limited editions marketed specifically for collectors. More important was the camaraderie found among the boxes of dog-eared back issues: the local comic book store was a place where, as the song goes about another beloved local establishment, everybody knows your name. It was a haven for the superheroically inclined habitués. “When [our customers] took the comics home, do you think they talked to their wives about Spawn?” asked Mike Malve. “Do you think they talked to their buddies at work about—hey, what’s going on in Spider-Man?”

The collector’s movement of the early 1990s burst forth with the same kind of unexplained, remorseless energy with which Doomsday burst forth from his underground prison. The bubble exploded almost as quickly as Doomsday was vanquished. Superman, of course, survives to this day; and although the Man of Steel has had his day in our yellow sun as an icon for commercial merchandise, even he must have chafed at the idea of being reduced to a commodity.

A not-so-modest proposal from the groundbreaking Batwoman #17 (May 2009).

The first superhero to come out: Northstar in Alpha Flight #106 (1992).

he notion espoused by Frederic Wertham in the 1950s, that Batman and Robin were in a homosexual relationship, has always been derided as “Exhibit A” when critics cite the destructive ridiculousness of Wertham’s crusade against comics. But—let’s be honest—hasn’t this thought, however fleetingly, crossed the mind of most adults who’ve read their adventures?

he notion espoused by Frederic Wertham in the 1950s, that Batman and Robin were in a homosexual relationship, has always been derided as “Exhibit A” when critics cite the destructive ridiculousness of Wertham’s crusade against comics. But—let’s be honest—hasn’t this thought, however fleetingly, crossed the mind of most adults who’ve read their adventures?

According to Grant Morrison, such an inference “was an inevitability. You could quite easily dial up those epicene qualities of the Batman myth in an adult way—this Plutonian, lawless man who lives in a cave and recruits young boys to help him in a vague and obscure war against crime … yeah. But for the children who were reading those books, and even probably for the young servicemen who were reading them, it was all about adventure and there was no sexuality in those stories at all, really. Still, it is a funny perspective.”

It is a perspective reinforced by essential elements in superhero mythology: guys and gals with secret identities dress up in colorful tights and capes, and step out into the night. Michael Chabon meditated on the idea in a 2008 essay in the New Yorker called “Second Skin”: “Superheroism is a kind of transvestism; our superdrag serves at once to obscure the exterior self that no longer defines us while betraying, with half-unconscious panache, the truth of the story we carry in our hearts, the story of our transformation, of our story’s recommencement, of our rebirth into the world of adventure, of story itself.” Artist Phil Jiminez sees a more direct connection to the superhero universe and gay culture:

Certainly I’ve been to enough conventions to know that superhero comics have an enormously large gay fan base. I often get in trouble sometimes for saying that superheroes are essentially big drag queens. They are disguises that normal people put on to go behave outrageously: it’s drag, it’s costume, it’s larger than life. The notion that you’re a mild-mannered kid at school, but when you take off your shirt elsewhere—not literally of course—but that you reveal that you are something underneath; that’s a very potent metaphor for gay kids.

In a 2010 New York Times story by George Gene Gustines, a book editor named Dan Avery was interviewed at “Skin Tight,” a regular social event at the historic Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, where attendees dress up in Spandex as their favorite superheroes: “Growing up in the ’80s, I guess I didn’t even think gay superheroes or supporting characters were a possibility. I do remember feeling like I had two secrets I had to keep: being gay and being a comic-book fan. I’m not sure which I was more afraid of people discovering.”

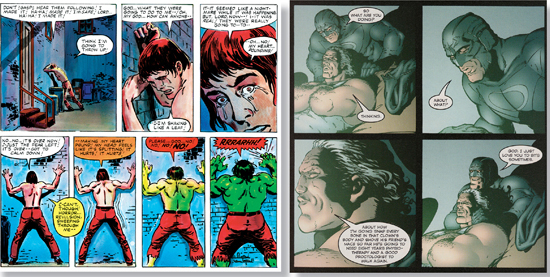

LEFT: “Doc” Bruce Banner barely escapes a homosexual assault in Hulk Magazine #23. RIGHT: In The Authority #15, Apollo and the Midnighter lead a happy home life.

The emergence of the first unapologetically gay character would appear in 1992, in the pages of Alpha Flight, a Marvel Comics title about a Canadian superhero group with its roots appropriately in the universe of the X-Men, who, in its acceptance of outsiders, had preached tolerance for decades. However, the journey to an “out” hero was fraught with difficulty—the Comics Code had specifically proscribed depictions of homosexuality (which they initially referred to as “deviancy”) until 1989—and some early attempts at showing gay characters were not always salubrious; in one infamous Incredible Hulk tale in 1980, the monster’s alter ego, Bruce Banner, is almost sexually assaulted by two men in a Y.M.C.A. The Alpha Flight story, in issue #106, featured one of its leading characters, Northstar, yet another super-streaking speedster previously distinguished only by his French Canadian name, Jean-Paul Beaubier. While trying to save an AIDS-infected baby, Northstar runs afoul of a retro Canadian hero from the 1940s—Major Mapleleaf (that’s his name!)—whose son has died of AIDS. Furious that his son had been marginalized, Mapleleaf takes out his frustrations on Northstar who, in the heat of battle, proclaims, “I am gay!”—which only makes Mapleleaf more furious: “By not talking about your lifestyle—by closeting yourself—you’re as responsible for my son’s death as the homophobic politicians who refuse to address the AIDS crisis!” A final tableau reveals a newspaper front page with the declaration of Northstar’s homosexuality. If the Alpha Flight issue had its share of purple prose and contrived situations, well, it wasn’t the first awkward “coming out”—and it wouldn’t be the last.

Northstar’s declaration threw open the doors of the Spandex Closet: even the New York Times editorial page commented on it: “Mainstream culture will one day make its peace with gay Americans. When that time comes, Northstar’s revelation will be seen for what it is: a welcome indicator of social change.” Other Marvel characters who followed in Northstar’s fleet footsteps were Hulkling and Wiccan, two Young Avengers, who maintain a committed relationship. When two other male, somewhat mysterious, X-Forcers, Rictor and Shatterstar, sealed their relationship with mainstream comics’ first gay kiss in 2006, their initial creator, Rob Liefeld, who introduced the characters in 1991, expressed his displeasure on the Internet; it did not earn him a lot of popularity. Peter David, who wrote the X-Factor issue that highlighted Rictor and Shatterstar’s relationship, commented, “I understand that some parents have the same reaction. They were responsible for their children’s appearances and, when informed of their sexual persuasion, firmly declare it’s impossible, they can’t be gay.”

Jim Lee’s Image Comics imprint, Wildstorm, ran a series called The Authority, a rather grimmer version of Justice League; its Superman/Batman avatars, the characters Apollo and the Midnighter, were not only lovers, but, in 2006, were also the first gay couple to be married in superhero comics. That year, DC reintroduced the Batwoman character as having a lesbian alter ego, Kate Kane; she would eventually enter into a relationship with Renee Montoya, a lieutenant in Gotham City’s police force who would herself eventually transform into a superhero called the Question. (Batwoman proposed marriage to a different girlfriend in 2013; all of this amused fans and comic book historians who remembered the original Batwoman character who was introduced in the 1950s, ostensibly to counter perceptions about Batman and Robin’s relationship.)

Astonishing X-Men #51 featured a slightly different Marvel marriage event: the first gay wedding in mainstream comics (art by Dustin Weaver and Rachelle Rosenberg).

During the evolution of all these other relationships, Northstar had been dating a non-superhuman named Kyle throughout his various adventures (they often found it hard to date because of Northstar’s crimefighting obligations). In spring 2012, Northstar proposed marriage and in issue #51 of Astonishing X-Men, he and Kyle were married in Central Park. Presented at the height of the presidential campaign, where gay marriage had become a contentious topic, there was inevitably some discord reflected among the wedding attendees in the comic book as well. “I’m a progressive guy, but it’s a lot to take in, huh?,” remarked a fellow member of Alpha Flight. But the wedding, which received massive media attention, went through without a hitch—surprising, since most weddings in the Marvel Universe involve some barrage of supervillains trying to crash the party. Northstar and Kyle rather stole the thunder that same month from DC’s big news that their “Earth-Two” Green Lantern, based in the 1940s, was actually gay. By then, this earth(s)-shattering news was greeted with a collective yawn by fans: been there, done that.

“The Marvel universe and the DC universe each have about 5,000 different characters,” said Jiminez. “The sheer size of those rosters creates a place for people of all stripes—but particularly gay ones—to connect, imagine, and project themselves in a world that reflects their own reality.” An unfortunate reflection of that reality was the reaction of the conservative family values group One Million Moms to the marriage of Northstar and Kyle in The Astonishing X-Men: “Children desire to be just like superheroes,” members posted on a website. “Children mimic superhero actions and even dress up in costumes to resemble these characters as much as possible. Can you imagine little boys saying, ‘I want a boyfriend or husband like X-Men?’ ” The web post didn’t make it clear whether the group objected to their little boys marrying a man or marrying a mutant.

The Savage She-Hulk wrestles Tony Stark in Girl Comics #1 (art by Laura Martin and Amanda Conner).

hat little lady sure is tough!” remarked a (male) bystander on the third page of Ms. Marvel’s first adventure in 1977. “She makes Lynda Carter look like Olive Oyl!” That ostensibly enthusiastic statement packs much of the trials and tribulations of being a female superhero at the end of the 20th century—as well as the role of women creators, editors, and readers within the overwhelmingly boyish men’s club that is the comic book universe.

hat little lady sure is tough!” remarked a (male) bystander on the third page of Ms. Marvel’s first adventure in 1977. “She makes Lynda Carter look like Olive Oyl!” That ostensibly enthusiastic statement packs much of the trials and tribulations of being a female superhero at the end of the 20th century—as well as the role of women creators, editors, and readers within the overwhelmingly boyish men’s club that is the comic book universe.

Ms. Marvel was a character whose alter ego had existed in the Marvel Universe for nearly half a century. She first appeared as Major Carol Danvers in one of the last original superhero titles of the 1960s, Marvel Super Heroes. Danvers was a NASA security officer who tangled with a new character named Captain Marvel, a somewhat uninspired character who was actually a military officer from an alien race called the Kree named Mar-Vell. (It was important to Stan Lee, Mar-Vell’s creator, and publisher Martin Goodman that the “Captain Marvel” name be wrangled from legal oblivion after the Fawcett character vanished in 1951.) In one issue, Danvers was rescued by Mar-Vell from an explosive bolt of radiation (from the Psyche-Magnitron!) expended by a Kree adversary. Unbeknownst to either of them, Carol absorbed some of the energy through Captain Marvel, and her human DNA was fused with Kree DNA (or the alien equivalent). She had become a sleeper superheroine.

Eight years later, Lee wanted to create a new title with a superpowered woman at the center of it and called Danvers up for active service. Along with Gerry Conway, they spliced together the “Marvel” name with the prefix that signified the women’s liberation movement, giving the new character that unique mixture of trendiness and corniness which typified the Marvel Universe. Danvers was now an editor of a women’s magazine (shades of Gloria Steinem, whom she resembled), published begrudgingly by none other than J. Jonah Jameson, Spider-Man’s nemesis. She frequently suffered from dissociative blackouts, when she would turn into the feminist warrior Ms. Marvel, whose powers included superstrength, flight (courtesy of a Kree-engineered suit, with matching scarf), and a “seventh sense” that alerted her to danger.

Ms. Marvel breaks through (cover by John Romita), and shows she can hit with the best of them (art from Ms. Marvel #1 by John Buscema).

Ms. Marvel zoomed across the Marvel Universe in her own title for several years before it was cancelled (at least she got a much sexier costume in the process), but the demise of her comic book was nothing compared to the indignities heaped upon her by editors over the next few decades. Soon after becoming a farm-team member of the Avengers, she was impregnated by one cosmic supervillain so that she might bear his child (she did, and it turned out to be the supervillain himself—don’t ask). Her fellow Avengers (which included another superheroine, the Wasp) barely acknowledged that Ms. Marvel had essentially been raped; furious at their dismissive attitude, she joined the X-Men for a while, only to be transformed into an alien energy-force humanoid called Binary. That didn’t do much for fans, so she was given back her normal human form and renamed Warbird, along with a diminution in her superpowers. As Warbird she rejoined the Avengers as a reliable rock ’em-sock ’em teammate, only to develop a drinking problem as a result of feelings of inadequacy. Warbird’s subsequent negligence and sloppiness in the field of battle forced Captain America to move toward court-martialing her; she quit the Avengers instead.

A sisterhood collapses: Carol Danvers rejects the Wasp’s condescension, in Avengers #200, (art by George Pérez); Gail Simone was the writer for the femme fatale full house of Birds of Prey, including the Huntress, Catwoman, and Katana.

If Ms. Marvel’s travails seemed unduly harsh and her treatment at the hands of male writers, artists, and editors seemed unnecessarily misogynistic, she wasn’t alone. By 1999, the plight of superheroines in general was finally acknowledged by a fan named Gail Simone who posted a blog entitled “Women in Refrigerators.” The name referred to a much-decried Green Lantern story from 1994 where the current iteration of the emerald ring-wielding hero came home to find his girlfriend dead, mutilated, dismembered, and crammed into a refrigerator by his current arch-nemesis. Simone simply tallied up all the superheroines (and girlfriends of superheroes) who had been “killed, maimed, or depowered” in comic books; the list was long and, taken as a whole, a condemnation of the male-dominated industry. Next to Ms. Marvel’s name and list of depredations foisted upon her, Simone simply commented: “SHEESH!,” employing one of Stan Lee’s favorite expressions of chagrin.

The happy ending to the refrigerator story is that Simone was eventually hired as a comic book writer, first by Marvel Comics, and eventually with a long-term contract at DC Comics. In 2003 she took on the only really major all-female superhero group, Birds of Prey, a snappy, aggressive team fronted by Oracle—the former Batgirl who had been rendered paraplegic by the Joker—now one of comic’s most assertive and brilliant characters. Simone also became the longest-running female writer ever to render the adventures of Wonder Woman, beginning in 2007. Her point of view about superheroines (and refrigerators) was simple: “If you demolish most of the characters girls like, the girls won’t read comics. That’s it!”

Still, female characters continued to be demolished: in one outrageous sequence during the 2004 Identity Crisis series, the wife of DC’s Elongated Man hero, Sue Dibny, was raped by a second-rate villain in the Justice League’s headquarters and subsequently murdered. It was paradoxical that such “refrigerator” moments occurred at DC in the 1990s into the 21st century, as the company had been led by a woman since 1976. Jenette Kahn was a publishing wunderkind in her twenties, energizing a host of teenager magazines, when Warner Communications brought her on board to revitalize its superhero publications and the way they met the public. She became President of DC Comics in 1981 and steered the company through several successes, not the least of which was pioneering relationships with creators that gave them unprecedented royalties and participation. Before Kahn stepped down in 2002, she promoted Karen Berger to become editor of DC’s groundbreaking Vertigo line in 1993; Berger was generally regarded to be one of the industry’s most sensitive and courageous editors; she served out her tenure until 2013.

The infamous “woman in a refrigerator” sequence from Green Lantern #54 (1994).

One of Kahn’s greatest achievements, by her own reckoning, is that “when I came to DC Comics we were 35 people on staff, two of whom were women—one secretary and one in production. By the time I left DC, we were 250 people of which half were women. As women got more involved in the workplace, and as creators of comic book stories, the things that perhaps were directed solely to a young male reader began to be directed also to young women as well.” Kahn still realizes that comic book superheroes have traditionally had the imprimatur of a male fantasy audience and male fantasy creators: “I always said that the [male] artists drew the men they wanted to be like and the women they wanted to be with—which is why they often had pneumatic breasts.”

Whether or not female superheroes will ever really share the dais with the male superheroes at the Comic Book Hall of Fame awards dinner remains to be seen. But, for what it’s worth, poor Ms. Marvel’s career appears to be on an upswing. Thanks to the sponsorship of Iron Man (himself a recovering alcoholic), Carol Danvers got herself straightened out, rejoined the ranks of the Avengers, and reclaimed the name of Ms. Marvel. After proving her worth to Captain America one more time (tough taskmaster, that Cap), he encouraged her to assume the mantle of the great Kree warrior (who had been killed off a few years before). So, in 2012, Carol Danvers was given her own Captain Marvel book, complete with a smashing new uniform, a great haircut, and a female writer, Kelly Sue DeConnick. “[The use of ‘Ms.’] made her feel like an auxiliary character,” said DeConnick, who insisted on the name change. “She got her powers from Captain Marvel and he’s gone. If somebody’s going to pick up that mantle, it’s Carol. She’s knew him, she respected him, she shares his DNA. She’s earned it.”

Ms. Marvel gets a well-deserved promotion to Captain Marvel (art by Ed McGuinness).

The new comic was subtitled “Earth’s Mightiest Mortal” in a wink to the original Captain Marvel from way back when. It was about time.