Zander and M.K. and I were on our way to dinner that night when we heard someone yell, “Hey! Wests! Wait for me!”

We turned around and saw Sukey running up the path behind us. Her cheeks were pink, her eyes shining, and she was breathing hard. The air was growing colder by the minute, and the wind blowing Sukey’s hair across her face told us the storm had arrived.

“Sorry. I pretty much ran all the way from the library,” she said. “But I need to talk to you.” She pulled us off the path and into the trees and looked around carefully to make sure we wouldn’t be overheard. “I had an idea, and I went and investigated at the library and, well—Stop, Pucci!” Pucci had swooped down to alight on her shoulder, and he was playing with her hair, grabbing her curls with his beak and gently tugging.

“What?” I asked impatiently.

“Your father—Pucci! Sorry. Your father went there! He went to the place on the . . .” She lowered her voice even more, just mouthing the word map.

I stared at her. “What? How do you know?”

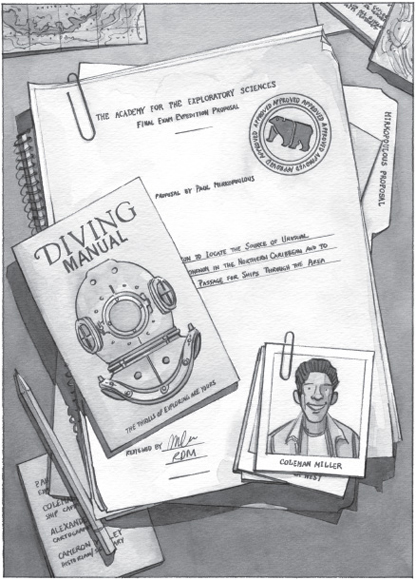

“Shhh. Look.” She slid a stack of papers from her jacket. “I remembered that they keep old Final Exam Expedition proposals and reports in the library. So I went and looked and, well, I had to take them when Mrs. Pasquale wasn’t looking. But—read this.”

We stood in a huddle in the woods, looking through the pages. During Dad’s last year at the Academy, someone named Paul Mirkopoulous had proposed “An Expedition to Locate the Source of Unusual Weather Phenomena in the Northern Caribbean and to Discover Safe Passage for Ships Through the Area.”

According to Mirkopoulous, a 100-square-mile region of the Northern Caribbean surrounding the newly discovered St. Beatrice Island had long been known as a dangerous passage for ships. He wrote in the proposal that newly invented diving helmets made of Gryluminum might allow him and his expedition crew to explore the floor of the ocean and discover if underwater features had anything to do with the disturbances.

“They were interested in Girafalco’s trenches, too,” I said.

“Look at this,” Sukey said, showing us the piece of paper that had been added to the proposal, listing the Explorers in Training who had been chosen as its crew. She had to hold the papers tightly so they wouldn’t blow away.

Someone named Coleman Miller had been named captain, and Paul Mirkopoulous had been the expedition leader. Dad had been the cartographer. Raleigh hadn’t been on the expedition, and neither had Leo Nackley. But I did recognize one more name: Cameron Wooley. He’d served as the expedition’s historian and secretary.

“This is great, Sukey,” I told her. “It’s the same information I found about King Triton’s Lair. The fact that Dad went there proves it. He wants us to go there, too.”

“Okay,” Sukey said. “But let’s say he did leave it for you because he wants you to go to the Caribbean. If I remember my Greek mythology correctly, King Triton lived under the water.”

“And how would we even get to the Caribbean?” Zander asked. “I don’t think Maggie is going to give us time off from school to go look for King Triton’s Lair.”

“No,” I said. “She’s not. But look at how Dad got there.”

“The Final Exam Expeditions,” Sukey said, grinning. “I like the way you think.”

“It won’t be easy,” I told them. “We’re going to have to propose an expedition without making anyone suspicious, and then we’ll have to get there and, somehow, look around underwater—alone. We can bring diving equipment, but none of us knows how to dive, and if the weather’s as bad as they say, well, it isn’t going to be easy.”

M.K. had been silent, listening to us, but now she spoke up. “I can handle the underwater part,” she said.

“What do you mean?” Zander asked.

“You’ll see soon enough. I’ve been working on something ever since you found the bathymetric map. So don’t worry about that part.”

“You really think we can do this?” Zander asked me.

“It’s the only way. We have to try, right?”

“But we can’t all turn in an expedition plan for the same place,” he said. “That would be sure to make them suspicious.”

“Of course we’re not going to turn in plans for the same place. I’ll turn it in. You heard what Foley said. I need to make it seem like finding this fuel source will save the world. Or us and our allies, anyway. And we’ll just have to hope we all get assigned to the expedition.” I was thinking out loud now. “I’ll write it so that it seems like each of you absolutely has to be on the expedition.”

“And if we don’t all get assigned?” Zander asked me.

“Then we’ll have to do as much as we can without the others.” I looked up at their stricken faces and said, “I know, I know. It’s awful to think of, but it’s the only way. Right? I’ll do some research and see if I can find anything. In the meantime, you should all be working on other plans. Do what you were going to do anyway. Just don’t make them very good.”

Sukey whispered. “He hasn’t come back, has he? The Explorer with the—” She pointed to her hand.

I shook my head. “No, but I think we just have to go ahead.”

We felt a few drops of rain, and then a few more, faster and harder. A thin line of lightning flashed over the mountains.

“This is crazy,” Zander said as we heard the crack of thunder and started sprinting towards the Longhouse. “There are so many ifs to this. A thousand things could go wrong.”

We kept running. No one said anything. We knew he was right.