“Land!” Pucci squawked. “Land ho!”

We steamed into St. Beatrice Harbor on January 7, eleven days after having left New York. It had felt much longer than that, and as I watched the island come into view, I realized how glad I’d be to be off the Deloian Princess. I’d gotten tired of the people, the Simalio, the smell of Dramleaf and wine in the lounge. I’d gotten tired of the endless expanse of turquoise sea.

“Lazlo, make sure you’re out in front,” Leo Nackley said as we all stood on deck, watching as we approached the colorful harbor ringed with palm trees. “The newspapers may be in port taking pictures. You’re the expedition leader. You should be in the picture.”

“Look at all the palm trees! And the flowers!” Jack exclaimed. For our arrival, he’d changed into a white suit and a bright yellow linen shirt that hurt my eyes. “Isn’t it beautiful? Almost as beautiful as you look today, Joyce.”

Joyce rolled her eyes.

“I don’t care what kind of trees they are as long as they’re growing in solid ground,” I grumbled. “I’m tired of looking at water.”

“Me too,” Kemal said.

“You do know that our expedition includes a whole lot of water, don’t you, West?” Lazlo Nackley said in a nasty voice.

“Really, Lazlo?” I replied without looking at him. “I thought we were sailing to the Gobi Desert.”

“Okay, okay,” said Mr. Wooley. “We’ve made it . . . this far, which is . . . good.” He gulped and put a hand up to his mouth. It was only the second or third time we’d seen him since we’d left New York. Lazlo had made endless comments about the uselessness of a faculty expedition leader who wasn’t seaworthy on an oceanic expedition. But even he seemed to feel sorry for Mr. Wooley at this point.

Leo Nackley raised his eyebrows at his son and smirked a little as Mr. Wooley went below deck again.

I was also looking forward to having a break from the Nackleys once we got to St. Beatrice. Zander, M.K., and I would be staying with Coleman Miller, Dad’s friend from the Academy who had been on the King Triton’s Lair expedition. The Nackleys, along with Joyce and Jack and Kemal, would be staying with some fancy BNDL higher-up on the island who would be helping us secure and outfit a ship.

We would have three days to stock the ship and make sure all of our equipment was ready before setting off on the trail of the oil. And Zander and M.K. and I would have three days to find out more about the exact location of King Triton’s Lair and the shipwrecks.

Pucci soared into the air to check out his new surroundings as the Deloian Princess docked in the harbor, its horn sounding our arrival and the people onshore waving enthusiastically. We’d gotten used to the humidity at sea, but there had been a constant breeze, and it seemed much hotter now that we were on the island. We found our luggage and told the porters to hold the rest of our equipment until we could load it tomorrow. M.K. didn’t want to leave Amy behind, but the porters swore they’d watch over her, and she reluctantly followed us down to the quay to meet Coleman.

The quay was lined with fishing shacks and offices, a busy jumble of people, animals, and machinery. The BNDL agents who had been on the ship took up position along the quay as we unloaded our gear. But in addition to the familiar agents, the port was full of soldiers, wearing their black-and-white uniforms and watching everyone getting off the boat. I watched as Leo Nackley went over to talk to one of them, gesturing in our direction.

Pucci nibbled on Zander’s chin.

“We’ll find you something to eat soon, Pucci,” Zander murmured, and Pucci gave a disgusted squawk.

“He’d better be careful once we’re out on the water,” Lazlo said. “I heard about sharks that can leap out of the water and snag seagulls from the air.”

“Are you kidding?” Joyce winked at M.K. “That parrot could whip any shark, no questions asked.” Njamba flapped down and settled on her shoulder. “He’s almost as brave as Njamba.”

Zander grinned at her. “That’s right. Any shark that messed with Pucci would be very surprised.”

Surprise! Pucci chortled. Surprise!

“That bird is weird,” Lazlo grumbled.

Finally a tall man in a tan canvas suit and pith helmet modified with lots of little gadgets came running along the quay and wrapped Zander in a gigantic hug.

“You’re here!” he exclaimed. “You’re finally here! I would have known you anywhere. You look just like your old Dad, you know.”

“Coleman Miller,” I said, and he turned to me, looking slightly confused. “I’m Kit,” I said. “And that’s our sister, M.K. You’ve already figured out that’s Zander.”

He wrapped me in a bear hug too, then turned to give one to M.K. “I couldn’t believe it when Raleigh told me you were coming to St. Beatrice. ‘They’ll have to stay with me,’ I told him. ‘No question about it.’”

Mr. Wooley had stumbled onto the quay, looking slightly green and extremely grateful to be on solid ground again.

“Cam! My old friend!” Coleman started to hug Mr. Wooley, but Mr. Wooley put a hand over his mouth again and waved him off. “Haven’t got your sea legs, have you?” Coleman said, laughing. “Don’t worry, a couple nights on St. Beatrice will set you right!”

Mr. Wooley tried to smile.

“Are you going to be okay, Mr. Wooley?” M.K. said.

“We’ll get him to the house,” Joyce whispered. “Don’t worry about him. See you back here at ten tomorrow to start on the provisions.”

I was sorry to see Joyce go. I’d enjoyed her company over the past eleven days. But I was pretty happy to see Lazlo walk away, cursing as he stepped in a pile of rotting fruit on the quay, his father berating him for not being more careful.

“Welcome to St. Beatrice!” Coleman said as we shouldered our backpacks and walked through a narrow alleyway between two tall brick buildings, one painted a bright cobalt blue and the other a watermelon pink. The direct noonday sun made its way down through the alley, illuminating the hundreds of seashells set into the brickwork. They formed a giant sun.

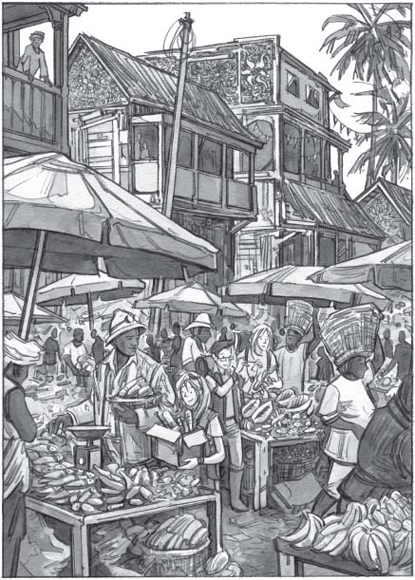

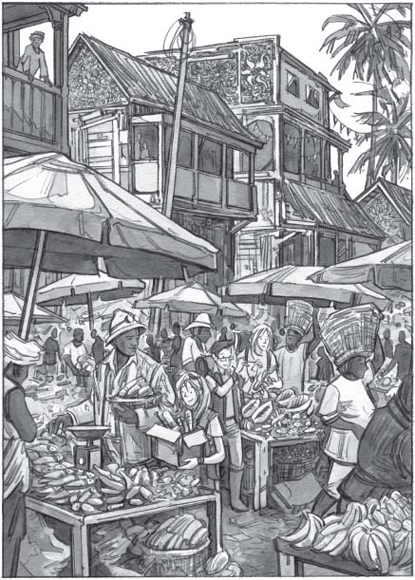

“Wow . . .” M.K. stopped at the end of the alleyway and pointed to the scene in front of her. “It’s so . . .”

“Colorful,” I finished for her. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything so colorful in my life.”

“That’s one word for the island,” Coleman laughed. “Colorful. We certainly are colorful!”

Stretched out in front of us, sloping down to the turquoise-blue sea, was a patchwork of pastel-colored houses, three or four stories each, with flowering vines twining around the white filigree porch railings. Many of the houses had huge murals on their sides. The murals were so finely done that they appeared to be painted. It was only when you looked closely that you saw they were collages made of different colored shells, stones, and bits of glass.

M.K. pointed at a mural depicting fishermen unloading their catch from a boat. Another showed a group of children carrying baskets of yellow and orange fruit. Another showed a group of brilliantly colored parrots in a tree. A few of the murals, I realized with growing interest, were maps.

My first impression of the island was of a prosperous paradise. But the closer I looked, the more the picture changed. The houses looked pristine at a distance, but as we walked by them I could see peeling paint and broken windows. There seemed to be a lot of people just standing around, and almost everyone looked hungry and thin. There were soldiers and BNDL agents on every corner.

Coleman led us through the narrow streets, pointing out buildings of interest as we went, stopping every once in a while to say hello to someone or hand a few coins to a barefoot child.

“St. Beatrice was explored a few years into the New Modern Age. I don’t say ‘discovered’ because as far as the Arawak people who were living here were concerned, they didn’t need to be discovered. They’d been here for a long time. They hadn’t wanted to be found. But then Jefferson Robbins showed up and reported back that they had an amazing fruit growing there, a fruit that was hardy and prolific and delicious. When the word got out about the Ribby Fruit, settlers came from all over the Caribbean. My family were farmers from Antigua, and we became farmers here. We did very well, enough that we could move to town and pay other people to tend to the crops, and I could go to the Academy for a couple of years. Fish and fruit from St. Beatrice are shipped all over the world now. When the crop is good, at least. But it hasn’t been, lately, and the government forces us to sell so much of our crop at the government rate.”

He stopped talking and quickly scanned the streets. In a whisper, he added, “Times have been tough the last year. I don’t know what they need so much fruit for. Sending it off to the territories and colonies where they can’t grow things, I suppose. And now they have their own government farms. They’re bringing labor in from all over the Caribbean, and everyone says they barely pay their workers. Anyway, it doesn’t do to talk too much about all of that.” He gave a sidelong look, searching for agents, that we all knew well. I’d heard people call it the “New York glance,” but the truth was that we did it everywhere because BNDL agents were everywhere. I could see a few of them standing watch in the marketplace, their telltale black uniforms out of place amid all the color.

“Let’s go this way,” Coleman said suddenly, and he took a quick turn into an alleyway. We followed him out the other end, and then we all took another quick turn into another alley, making a big circle and coming out near where we’d started.

“Sorry,” he said. “Thought I saw someone.”

“An agent?” I asked.

“No, no. Not an agent. Come on. Follow me. Here’s the market.”

I turned and looked behind me. It may have been my imagination, but I thought I saw a flash of black, someone who had been watching and then ducked out of sight.

We looked around at the people standing in line to get into the market. They were carrying baskets filled with mangos, bananas, breadfruit, and piles of the bright-green Ribby fruit. Others were carrying baskets filled with fish and giant lobsters. The soldiers stopped them and inspected the baskets, then sent them on their way into the stalls.

Coleman led us into the market, and we wandered for a few minutes while he bought fish and vegetables for dinner. M.K. found a stall that sold gadgets and engine components, and she bought some bolts and wires of different sizes for Amy. Zander and I looked at the shells for sale.

“That’s a Carib Cowrie,” Zander said. “And these I’ve never seen before. This looks like a whelk, but it must be a newly discovered species.” He bought a handful, and I bought a little cowrie shell suspended on a silver chain, thinking maybe I’d give it to Sukey, if I ever got the chance.

Zander and I walked by a row of stalls displaying exotic animals. Pucci had been sitting on Zander’s shoulder, but now he hopped along the line of cages, poking his head in to look at the birds and mammals and reptiles inside.

“This is awful,” Zander said. “That’s a Reingold Leopard. It shouldn’t be in a cage. And that’s an Oopala Pheasant. Someone should do something about these traders.” We stopped and looked at the beautiful bird. Its scarlet tail feathers drooped sadly.

Coleman came and we walked with him along the crowded, noisy streets until he stopped in front of a big, robin’s-egg-blue house looking out over the harbor.

“Here we are,” Coleman said. “Welcome to my home.”

Inside, the house was even bigger than it looked from outside. At one end of the living room a huge wall of glass windows looked out on the sea, which stretched out away from the coast, toward points unknown. We’d be sailing out that way in just a few days.

After he showed us our rooms, I took a steaming-hot bath in Coleman’s giant tub, looking out over the water and feeling the warm breeze coming through the open windows. The breeze smelled of flowers, and I felt almost recovered from eleven days at sea. When I came out, the others were getting dinner ready. M.K. was setting the table, and Zander was pouring fresh coconut water into glasses at each place setting. The dining room was decorated with paintings of St. Beatrice and other Caribbean islands, and there were more of the beautiful shells everywhere I looked.

“Coleman, what are those?” I pointed to the shell pendants hanging from nails on the wall. They were made from all different kinds of shells, some pink or pale yellow, some made of shimmery mother-of-pearl. Some were carved to look like flowers, some like animals or fish.

“Those are a traditional St. Beatrician art form,” he told me. “They’re whistles. Each one has a different sound—they’re in different keys and have different numbers of finger holes. The fishermen play them as they come into port at the end of the day so their families know they’re back. Listen.” He took one off the wall and blew through one end, then placed his fingers over the little holes to play a tune. I recognized it as “Spanish Ladies,” an old sea chantey that Dad used to sing.

Coleman grilled fish and vegetables on the terrace, and we sat down and dug into the best meal I could remember in a long time—since Dad’s disappearance, at least. The fish was crisp and brown on the outside and flaky white inside, tasting of lemon and herbs. Coleman had bought excellent bread in the market and I sank my teeth into a tender slab, my mouth filling with the fresh taste of salt and yeast. The coconut water was pure and cold and a couple of sips made me forget all about the warm, brackish water we’d had to drink on the SteamShip.

Coleman offered a toast. “In the words of the St. Beatrician sailors, may you find calm seas and fine weather. Now, tell me all about this expedition.”

We hesitated.

“Well,” said Zander. “It’s actually Lazlo Nackley’s expedition. He thinks we can find oil out there.”

“The underwater black waterfalls,” Coleman said. “He believes that old story, does he?”

“You don’t?”

“There are a lot of stories about what’s out there.” He winked. “Maybe three or four of them are true.”

I hesitated. “We’re a bit more interested in the shipwrecks in King Triton’s Lair,” I said. “You and Dad went looking for them, didn’t you? What do you remember about the expedition, Coleman?”

He leaned back in his chair. “I’ve been trying for a long time not to remember. It was that expedition that convinced me I didn’t want to be an Explorer. That’s why I left the Academy. The shipwreck haunted me. Better to follow my father into farming.” He took a long sip of his coconut water. “I remember a few things. What do you want to know?”

“Where had Paul Mirkopoulous heard about King Triton’s Lair? How did he get interested in coming here?”

“It wasn’t Paul. It was your father. I don’t remember why they put Paul’s name on the expedition, but it was Alex’s show all the way.” Zander and M.K. and I exchanged glances around the table. “Your father was the one who wanted to see if he could find the shipwrecks at King Triton’s Lair.”

“What happened? Mr. Wooley said a storm came up and the ship sank.”

“Children growing up in this part of the Caribbean are told in the cradle not to go near King Triton’s Lair,” Coleman said grimly. “When I was a young man, I heard stories about what happened to sailors who strayed too close. Your father convinced me to go along on the expedition. I don’t know why I agreed. Pride, I suppose. I didn’t want them to think I was a coward. But now I wouldn’t go near it for all the Ribby Fruit in the world. We sailed out for a day or so. Your dad and Paul had some coordinates they’d found and we set a course. But before we got very close, we ran into a terrible storm.”

Coleman described almost the exact series of events that Mr. Wooley had, right down to being rescued by the fishing boat.

“It’s a miracle your father survived. He didn’t say much about what had happened during his time on that raft, but it must have been awful. I’ve known a few fishermen who survived shipwrecks, who spent time on pieces of their boats at sea. They never get over it. The sharks. And there are stories about other, more terrible things. . . I don’t know why you want to go there. I don’t know why they’d let you.”

“So you really don’t think there’s oil out there?”

“There may be oil. But whether you can get to it without killing yourselves is a different question.”

He took a deep breath and pasted a smile on his face. “Now, let’s talk about something happier. Have you ever tasted Ribby Fruit cake? No? Well, you are in for a treat.”