“Look at her. She’s a beauty!” M.K. squealed.

Zander whistled. “She sure is. Wow.”

We all stared up at the catamaran’s huge mast, the mainsail a mosaic of colored sailcloth forming the image of a mermaid staring with placid confidence out to sea. The boat’s two broad hulls were made of gleaming dark mahogany, each big enough to contain berths and common space for an even bigger crew than ours. The St. Beatrice boatbuilders were renowned for their expert craftsmanship. Based on traditional multihulled boats, catamarans were faster and more stable than single-hulled vessels. The Beatrician fishermen and seal hunters used them to sail out into the deep waters of the northern Caribbean, precisely where we’d be heading in a couple of days.

Bright red letters painted on the front of the hull spelled out her name: the Fair Beatrice. There was a large covered cockpit at the center of the bridge and painted wood mermaid figureheads mounted on each of the hulls.

“Beauty!” Pucci squawked. “She’s a beauty!”

Jack greeted us on deck. He wore bright white pants and a white jacket, a green silk scarf tied around his neck.

“I wouldn’t wear that getup if I were you, Jack,” M.K. said. “Someone might accidentally spill engine grease on you.” He stepped back, a protective hand over the front of his shirt.

Joyce, wearing her navy canvas sailing jacket, Njamba perched on her shoulder, laughed. “Come on,” she said. “I’ll give you a tour.”

Everything was shining and new belowdecks, a roomy galley for cooking meals and three berths in each hull.

“This is more than a fishing boat,” Coleman said, running a hand across the gleaming surface of the mahogany chart table. The top lifted to reveal a deep compartment for the charts we’d use to plot our course. “I’ve seen a lot of boats, but this is something else. Where’d you find this lovely lady?”

“She belongs to a generous BNDL official,” Lazlo Nackley said, coming out from one of the berths. “He only agreed to loan her to the expedition when he heard that I was in charge.”

I thought about how much Sukey would have liked the Fair Beatrice. She was a pilot, after all, and even though she wasn’t a glider or a plane, the boat would have been right up Sukey’s alley.

Coleman inspected her carefully. “She looks sound enough,” he said. But his forehead was creased with worry as he looked around.

Joyce showed us the stern hatch through which you could climb back up on deck, then led us up the companionway back to the cockpit. Mr. Wooley sat in a chair on deck. He still looked ill, his face pale, his hands shaking.

“Can’t believe they convinced you to sign on again, Cam,” Coleman said. “I wouldn’t have thought you’d want to go out there for anything.”

“Let’s just say . . . it wasn’t my first choice, but I am an instructor at the Academy for the Exploratory Sciences and I’m willing to do my duty.” He sounded like someone was holding a gun to his back, forcing him to say the words.

Leo Nackley smiled.

Coleman raised his eyebrows. “There’s got to be more to that story, but I won’t squeeze it out of you. Good luck with your work today.” He told Zander, M.K., and me that he’d pick us up at the end of the day.

We spent the morning loading provisions onto the Fair Beatrice while Lazlo sat on deck and directed us. With the help of some fishermen Mr. Wooley had hired for the job, M.K. installed stern davits, metal arms usually used to hold and lower lifeboats, on the back of the boat, and secured Amy for the voyage. When we were ready, we could easily lower her into the water. While the rest of us stacked rice and dried pasta and salted meat and barrels of water into the hold, she tinkered with the submersible, making sure she was ready. Once the provisions were loaded, we helped to get the rest of the equipment on board, stowing the drills and pumps and containers Lazlo had brought to take oil samples back for BNDL.

While Joyce continued inspecting the boat, Zander and I offered to get lunch for everyone. We slowed our pace as we walked along the harbor, enjoying being away from Lazlo and feeling the sun on our faces. Pucci and Njamba flew above us along the quays, surprising the gulls looking for fish scraps by dive-bombing them and knocking them into the water.

“I thought Lazlo was going to throw Joyce overboard,” Zander said, smiling. “But she knows how to handle him. I’m glad she’s along.”

“Me too.”

We walked in silence for a little while, watching the two birds harass the poor unsuspecting gulls. “What are we going to do once we’re out there, anyway?” Zander said. “Do you think there’s any way we can look for the shipwrecks with Lazlo obsessed with finding the oil?”

I thought about the Explorer with the Clockwork Hand. “We’ll have to find a way,” I told him. “I’ve been thinking about it, and Lazlo is our only problem. Jack doesn’t really care and I think Mr. Wooley will be willing to look the other way.”

“So what? We’ll get into Amy and just escape? How long did M.K. say she could stay underwater?”

“I think she said four hours.”

“And then what?” He frowned. “Do you really think Lazlo is going to just let us get back on the boat after we abandon his expedition?”

“You’re right,” I said. “We’ll have to do it at night, without him knowing. Maybe we can do it when Joyce is on watch. I don’t think she’d give us up.”

“I don’t think she would either, but it just seems risky, Kit.”

“It’s the whole reason we’re here,” I said. “We have to find whatever it is that Dad wants us to find in the shipwrecks. It’s something big. Something important. The Explorer said that everything could depend on us finding the shipwrecks. If you had talked to him, you’d know what I mean.”

Zander stopped. “But I didn’t talk to him, did I? No one but you has ever met this guy or even seen him.”

We stared at each other. Pucci swooped down and landed on Zander’s shoulder for a moment, then flapped after Njamba again, cackling loudly.

“You think I’m making it up?” I asked.

“No, of course not. I just don’t see how we’re going to pull this off.”

If I was being honest, I didn’t either, but I didn’t say anything. We continued down along the harbor, which was ringed with palm trees and brightly painted shops and warehouses. We listened to the fishermen sing sea chanteys about whale hunts and mermaids beneath the sea. Dad had loved sea chanteys and Zander and I stopped to listen to the hearty voices singing in unison as the men scrubbed and painted their boats and repaired their nets.

’Twas Friday morn when we set sail

And we had not got far from land

When the captain he spied a lovely mermaid

With a comb and a glass in her hand

Oh, the ocean waves may roll

And the stormy winds may blow

While we poor sailors go skipping aloft

And the landlubbers lay down below, below, below

And the landlubbers lay down below

“You the boys going out to King Triton’s Lair?”

We jumped.

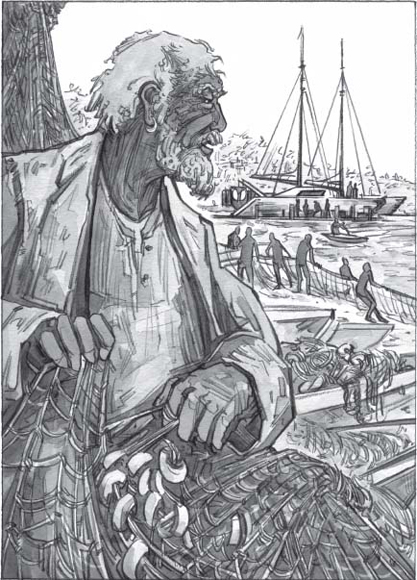

An elderly man was sitting outside one of the little shacks by the harbor, working away on a big fishing net made from small sticks and rope. “You the boys?” he asked again.

He was very old, his skin wrinkled and folded like old cloth. His eyes were watery and unfocused as he looked up at us.

“We’re on an expedition from the Academy for the Exploratory Sciences,” I said.

“Idiots,” he replied.

Zander and I glanced at each other. “What do you know about King Triton’s Lair?” I said.

“I know a lot.” He snorted and went back to his fishing nets. “Why do you want to go there?”

I decided we didn’t have anything to lose by being halfway honest with him. “We’re hoping we can find the shipwrecks and maybe the oil,” I told him.

“That’s why I wanted to go, too,” he said. “And I almost died. The storm came out of nowhere. I barely knew it had started to blow before the ship went under. My cousin who was with me that day, he died in the sea.”

I took out a map of St. Beatrice and the surrounding ocean that I’d scrawled on a scrap of paper. “Where was your boat when you sank?” I asked him. “Can you show me?”

He looked up at me again and pointed to a place on the map and I marked it down. I could figure out the coordinates later, but it looked to be near to the location of King Triton’s Lair on Dad’s map.

I thanked him.

At first I thought he wasn’t going to say anything else, but as we started to walk away, he muttered, “You won’t find the oil. It’s just a story. But King Triton’s Lair is out there, the weather is out there. There is a song that the fishermen sing that goes:

Don’t go down below, boys

Don’t go down below

For if you go with Triton

You’ll never come up no more

I turned back and met his eyes. “If you try to go there, you are as stupid as all the rest.” He was finished. He resumed his work on the net.

Zander and I were silent as we approached a little stall selling fried fish and Ribby Fruit cake. We bought enough for everyone and brought it back to the Fair Beatrice.

Coleman met us at the end of the day, and after we’d said goodbye to the others, we told him and M.K. about our conversation with the old man.

“That’s Papa Madigan who you met. And he’s right, you know,” Coleman said. “I’ve been thinking about it all day, and this is crazy. I don’t know why the Academy is letting you do this. I don’t know why Leo Nackley is letting his son risk his neck. And I don’t know why I’m helping you. I agreed to Raleigh’s request to have you stay with me because of your father, but if something happens to you, I’ll never forgive myself.” Suddenly, he looked over his shoulder and said, “Quick, follow me.”

He steered us into an alley. We followed his lead and pressed ourselves against the wall. Coleman looked out, but no one walked by. “Okay,” he said. “This way.” We ran down to the end of the alley, took a quick left onto a busy street, and then ducked into another alley. “Out here and . . .” he stopped and looked back down the alley. “Okay, I think we lost him.”

“Lost who?” I turned around but didn’t see anyone.

“The man who was following us,” Coleman said. ”I think he followed us the day you arrived too, but I can’t be sure.”

“But who is he?”

“A BNDL agent, a spy—who knows?”

“What kind of spy?” Zander said.

“St. Beatrice is full of spies,” Coleman answered. “Indorustans, government spies. Pirates who want to know the details of Ribby Fruit shipments so they can seize them. Could be anyone. It could be me they’re following, but I think someone is interested enough in your expedition to be following you. I’ll say it again: I think you’re crazy. Why did they put you on Lazlo’s expedition, anyway? He doesn’t trust you. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“Why would they follow you?” Coleman was just a farmer. A fairly successful farmer who had spent two years at the Academy for the Exploratory Sciences, but still.

“I am involved in certain political activities that make me a target,” Coleman said. “There are good people on this island who don’t like the things being done in their name.” Something about his face stopped me from asking any other questions.

We walked the rest of the way in silence.

We spent the next two days working on the boat and getting ready to go. The night before our departure, Coleman told us to be home early for dinner because he had a surprise for us.

“I bet it’s another Ribby Fruit cake,” M.K. said as we made our way through the bustling marketplace. “I love how it’s all crisp on the outside and then the fruit stays kind of gooey, like jam. Mmmm.”

“Maybe he’ll send some Ribby Fruit cakes with us for the expedition,” Zander said. “After seeing all that salt cod and rice in the hold today, I’m starting to think we shouldn’t ever leave Coleman’s.”

We found him in the kitchen back at his house.

“Now for my surprise,” Coleman said, smiling mischeviously. “I’m actually quite amazed that we managed to pull it together. But . . . well, you’ll see. Follow me.”

We didn’t so much follow him out to the terrace as push and run past him when we saw the lone figure standing at the far end of the railing, looking out over the water.

She turned around.

“You didn’t think I was going to let you have all the fun while I rotted away with the Snow Deer, did you?” Sukey grinned and wrapped M.K. in a huge hug. “You guys think Lazlo will let me tag along?”