CHAPTER 2 Problem Blindness

In 1999, the doctor and sports trainer Marcus Elliott joined the staff of the New England Patriots, whose players had been plagued by hamstring injuries. At the time, there was a kind of fatalistic mind-set about injuries. People thought that injuries were “just a part of the sport,” said Elliott. “It’s just the nature of the sport and they’re just freak injuries.” Football is a tough game; players will get hurt. It’s inevitable.

Elliott’s philosophy was different. He thought that most injuries were simply the result of bad training. In most NFL training environments, the focus was on getting bigger and stronger. Even though players’ bodies—and the positions they played—differed greatly, the training was mostly the same. “It’s almost like walking into a doctor’s office and—without interviewing you, without conducting any tests on you—he gives you a prescription,” he said. “It makes no sense. But that’s how the training of professional athletes was conducted.… It was a one-size-fits-all program.”

Elliott brought a new, individualized approach. Players who were more at risk of hamstring injuries, such as wide receivers, got more attention. Elliott studied each player, testing their strength and watching their sprint mechanics and hunting for muscle imbalances (say, if one hamstring was stronger than the other). Based on those assessments, the players were put into groups by their risk of injury: high, moderate, and low. The high-risk players went through aggressive off-season training to correct the muscular warning signs that Elliott found.

The prior season, the Patriots players had suffered 22 hamstring injuries. After Elliott’s program, the number plunged to 3. The success—and others like it—made believers out of skeptics. Twenty years later, the data-driven, player-tailored approaches, of the kind used by Elliott, have become much more prevalent.

Elliott later founded a sports science firm called P3, which assesses and trains elite athletes. The firm uses 3-D motion capture technology to micro-analyze athletes while they run, jump, and pivot. The results can be astonishingly precise: kind of like an MRI for elite athletes. Elliott can sit with an athlete and narrate: See, when you land after a jump, you’ve got 25% more force coming through one side of your body, and we’re noticing that your femur is rotating internally, and your tibia is rotating externally. That puts your relative rotation at the 96th percentile of the athletes we’ve examined, and every single athlete we’ve seen above the 95th percentile has suffered a knee injury within two years. So we should work on that, and after we train it, we are going to reassess it to see how much it has changed. More than half of the current players in the NBA have been analyzed by P3.

“You don’t wait for these bad things to happen,” said Elliott. “Instead, you look for the signal that there’s a risk there, and then you act on it. Because if you wait for the bad things to happen, you can never quite put things back together the way they were before.” Elliott—and his peers with a similar philosophy—have made the science of injury prevention increasingly prevalent in pro sports.

Pro athletes play hard. Injuries are gonna happen. You can’t change that. That mind-set is an example of what I’ll call “problem blindness”—the belief that negative outcomes are natural or inevitable. Out of our control. When we’re blind to a problem, we treat it like the weather. We may know it’s bad, but ultimately, we just shrug our shoulders. What am I supposed to do about it? It’s the weather.

Problem blindness is the first of three barriers to upstream thinking that we’ll study in this section. When we don’t see a problem, we can’t solve it. And that blindness can create passivity even in the face of enormous harm. To move upstream, we must first overcome problem blindness.

In 1998, the graduation rate in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) was 52.4%. A public-school student in Chicago had a coin flip’s chance of getting a high school degree. “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets,” wrote the health care expert Paul Batalden. And CPS was a system designed to fail half its kids.

Imagine that you were a teacher or an administrator inside this system, a good-hearted person eager to change those intolerable odds. Where would you start, exactly? Your noble aspirations would soon smack into the sprawling mass of CPS, with its 642 schools, 360,000+ students, and 36,000+ employees. For a sense of scale: the school district in Green Bay, Wisconsin, has 21,000 students. CPS has that many teachers. CPS’s $6 billion budget is about the same as the entire city of Seattle’s.

This is the story of how a group of believers tried to change a massive, broken system from inside—how they went upstream in hopes of stopping students from dropping out. To spark change, they first had to contend with a flawed mind-set. “For a long time, people had this notion—they think when you come to high school, you’re gonna make it or break it,” said Elizabeth Kirby, who as principal of Kenwood Academy High School was one of the change leaders. “For these kids, this is where we’ll decide who’s going to be successful and who’s not. And if they’re not successful, it’s their fault. And that’s just how it is—so no one questions it.”

That’s just how it is—so no one questions it. That’s problem blindness. Within CPS, many people had come to accept the high dropout rate. When students failed, they believed, it was because of root causes that were impossible to fix: poor families, inadequate K-8 education, traumatic emotional experiences, lack of nutrition, and more. On top of all that, the kids just didn’t put forth the effort: They missed class; they didn’t turn in assignments. They didn’t seem to care. What could a high school teacher or principal do to affect any of that? The whole situation seemed intractable, and when another year went by, and the graduation rate continued to hover around 50%, it reinforced their helplessness. It’s a tough world, but that’s the way it is, and I can’t do anything about it.

The first ray of hope—that school leaders could make a meaningful difference in the graduation rate—came from some academic research conducted by Elaine Allensworth and John Easton at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research (CCSR). In 2005, CCSR published its findings that you could predict, with 80% accuracy, which freshmen would graduate and which would drop out.

The prediction was based on two surprisingly simple factors: (1) a student’s completion of five full-year course credits; and (2) that student’s not failing more than one semester of a core course, such as math or English. Those two factors, combined, became known as Freshman On-Track (FOT) metric. Freshmen who were on-track by this measurement were 3.5 times more likely to graduate than students who were off-track.

“Freshman On-Track matters more than everything else put together,” said Paige Ponder, who was hired by CPS in 2007 to manage the FOT efforts. Conspicuously absent from the calculation were: income, race, gender, and—perhaps most incredibly—the student’s own academic performance through eighth grade.

On that last point: Students in the bottom quartile of eighth-grade achievement who stayed on-track as freshmen had a 68% chance of graduating—far above the district average. What the researchers had discovered was that there is something peculiar about a student’s achievement specifically in the ninth grade that predisposes them to succeed or fail in high school.

Why? What’s so special about ninth grade? Part of the answer was that, in Chicago, there’s no junior high: Elementary schools run from grades K to 8, and high schools start in 9th grade. So the pivot from eighth to ninth grade was a whopper of a transition: essentially a sudden graduation from childhood to adulthood.

“People are vulnerable during transitions,” said Sarah Duncan, whose nonprofit the Network for College Success played a critical role in the CPS work. She said that students will often get their first taste of failure in the ninth grade, and that teachers almost seemed to relish delivering it, in a tough-love kind of way. “Teachers thought that the kids [who failed] would think, ‘I need to work harder,’ ” Duncan said. “Sometimes that happens. But the majority of fourteen-year-olds, if they fail, interpret that as: ‘I don’t belong, I’m not good enough.’ They withdraw.”

But how do you keep students on track? Keep in mind: the FOT metric is just a prediction—it doesn’t solve anything, just as your smoke detector doesn’t put out fires. And like a smoke detector, if the alarm goes off, it means the bad thing has already happened; you’ve missed your chance to prevent the problem. (If a student finishes the freshman year off-track, the harm has already been done.)

Unlike a smoke detector, though, the FOT metric suggested a potential recipe for prevention: Make sure at-risk students can sustain a full course load and give them extra support in their core courses.I The quest to accomplish that mission upended CPS’s practices in countless ways.

For one thing, if ninth grade is the critical transition point, then you’ll want your best teachers teaching freshmen. That reversed the pecking order—usually the best teachers wanted to work with more mature juniors and seniors. But now you know that ninth graders deserve the A-team.

Also, seen through the lens of the FOT metric, certain discipline policies began to look self-destructive. “When we started this work, kids got suspended for two weeks all the time,” said Sarah Duncan. “Not for bringing a gun to school. For a scuffle in the hallway where no punches were thrown.” This was the “zero tolerance” era.

But what happens when at-risk students—those already struggling to hang on—are kicked out of school for two weeks? They fall behind in their coursework, fail classes, fall off-track, and don’t graduate. It’s unlikely any administrator realized that their get-tough policies might literally ruin a student’s career prospects.

Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.

The most profound change, though, was to the mind-set of teachers. The Freshman On-Track work “changes the nature of how teachers see their jobs. It changes relationships between teachers and students,” said researcher Elaine Allensworth. “It’s the difference from ‘I put the work out there and I assign the grades’ to ‘My job is to make sure all students are succeeding in my class. So I need to find out why they’re struggling if they’re struggling.’ ”

As a teacher, if you accept that your job is to support students, not appraise them, it changes everything. It changes the way you collaborate. For one thing, you can’t adequately support a struggling student by yourself. You might see her for only an hour a day. Is she struggling only in your class or in several? How often is she missing school? Have other teachers found better ways to reach her? In short, you need to know more about her, and you need collaborators.

Traditionally, teachers would meet by department—the social studies teachers would meet together, and the English teachers, and so on. But now teachers began to meet across disciplines in what were called Freshman Success Teams. They’d meet regularly to scrutinize data reports provided by the district that provided real-time information on a student-by-student basis. For the first time they could share a 360-degree view of each student’s progress.

“The beautiful thing about teachers—you can have whatever philosophy you want, but if you’re engaged in a conversation about Michael, you care about Michael,” said Paige Ponder, conjuring a hypothetical student. “It all boils down to something real that people actually care about.… ‘What are we going to do about Michael next week?’ ”

Every student needs something different. Aliyah needs extra help in math, but she won’t ask for it—if you offer it, though, she’ll accept it. Malik has to walk his sister to elementary school every morning, so he will always be late—he needs an elective as his first period, so that if his tardiness causes him to fail, it won’t be a core course. Kevin is a slacker and will dodge work when he can—but his mother will stay on him if you reach out to her. Jordan needs someone calling her house every single time she misses class. (Managing attendance is one of the most important parts of the FOT effort—as Ponder put it, “It’s so obvious that if you get through school, you will get through school.”)

Student by student, meeting by meeting, school by school, semester by semester, the numbers began to budge. Students’ attendance improved, their grades improved, and their on-track measures improved. And four years later, they graduated in greater numbers than anyone thought possible. By 2018, the graduation rate had vaulted to 78%—up more than 25 percentage points in 20 years—on the strength of the upstream efforts of hundreds of teachers, administrators, and academics.

A ballpark estimate is that between 2008 and 2018 an additional 30,000 students earned a diploma who, in the absence of the CPS effort, would likely have dropped out. Those graduates will never know that, in a slightly different reality where the FOT work was delayed or never started, they would have dropped out, and their lives would have been immeasurably harder.

Because they graduated, though, those students will see their lifetime wages increase on average by $300,000 to $400,000. The leaders at CPS won an upstream victory worth $10 BILLION and counting—and that’s tabulating just the extra income students will receive, not including the countless other positive ripple effects that come from higher incomes, from better health to greater happiness.

The story of CPS’s success foreshadows many of the themes we’ll explore in the book. To succeed upstream, leaders must: detect problems early, target leverage points in complex systems, find reliable ways to measure success, pioneer new ways of working together, and embed their successes into systems to give them permanence. Remember, though, that for anything to happen at CPS, leaders first had to awaken from problem blindness. You can’t solve a problem that you can’t see, or one that you perceive as a regrettable but inevitable condition of life. (Football is a tough game—of course, people are gonna get hurt.)

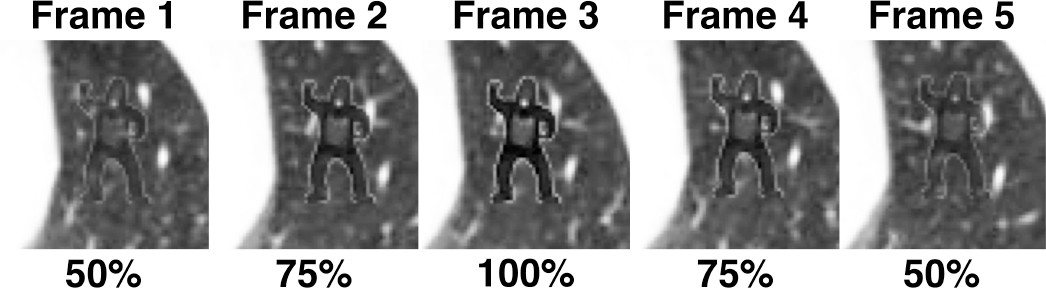

Why do we fall prey to problem blindness? For a clue, take a look at the image below, which shows several slides of a chest CT scan. It’s the kind of visual sequence that radiologists might analyze while hunting for lung cancer. Notice anything odd?

© [9/30/19] Trafton Drew. Image used with permission.

Yes, that’s a tiny gorilla, and no, this patient did not inhale it. The gorilla was inserted into the images by some researchers, led by Trafton Drew, who were playing a trick on a group of radiologists. How many of the radiologists—focused on a search for potentially cancerous nodules—would notice the gorilla?

Not many: 20 out of 24 missed it entirely. They had fallen prey to a phenomenon called “inattentional blindness,” a phenomenon in which our careful attention to one task leads us to miss important information that’s unrelated to that task.

Inattentional blindness leads to a lack of peripheral vision. When it’s coupled with time pressure, it can create a lack of curiosity. I’ve got to stay focused on what I’m doing. When teachers and principals are hounded to boost students’ test scores, year after year, and denied the resources they need to succeed, and buffeted by a never-ending series of regulatory and curricular changes, they lose their peripheral vision. They’re like radiologists scouring a scan so intently for nodules that they miss the gorilla. So, with time, they stop worrying about the graduation rate, because they’ve got more than enough on their plates already, and anyway, what could they do about it?

And, by the way, if you’re tempted to think less of these radiologists for their gorilla blindness, did you happen to notice that, when there was a section break earlier in this chapter, the normal section divider was replaced with a leprechaun? (In the print edition, we replaced several page numbers with leprechauns, which was good fun.)

My early testing with readers of the print edition suggested that about half noticed the trick and half didn’t. And even if they did notice it, the repetition caused their interest to fade. The first time someone saw a leprechaun in place of a page number, they thought, What the hell? A leprechaun? The second time, it was Oh, there’s another one. The fourth time, it had vanished from their consciousness. That’s habituation. We grow accustomed to stimuli that are consistent. You walk into a room, immediately notice the loud drone of an air conditioner, and five minutes later, the hum has receded into normalcy.

To reinforce that last point about attaining “normalcy,” consider that habituation is frequently used as a therapy for people’s phobias. People with a fear of needles, for instance, might be asked to look at images of needles, or to handle needles, so many times that eventually their irrational fear yields. The needle has been destigmatized. Normalized. In a therapeutic context, that normalization is desirable. But habituation cuts both ways: Imagine instead that what’s being normalized is corruption or abuse.

In the 1960s and 1970s, sexual harassment had been normalized in the workplace to the extent that women were actually encouraged to embrace it. Here’s Helen Gurley Brown, the longtime editor of Cosmopolitan, from her 1964 book Sex and the Office: “A married man usually likes attractive, approving females around him whom he may or may not think of as sex objects. (You’ll never get me to say this is wrong!) He may not be planning to bag you for his collection but only trying to ascertain your basic attitude toward men. One Little Miss Priss who thinks hemlock is preferable to sin, even when it isn’t her sin, can spoil a man’s pleasure in his work. An attractive girl textile executive says, ‘I’d rather have a man making a good healthy pass at me any time than have him cutting my work to ribbons.’ ” That is a real quote. It’s like she’s contracted sexual Stockholm syndrome.

A 1960 study by the National Office Management Association found that 30% of 2,000 companies surveyed agreed that they gave “serious consideration” to sex appeal in hiring receptionists, switchboard operators, and secretaries.

The term sexual harassment was coined in 1975 by the journalist Lin Forley, who’d been teaching a course at Cornell University about women and work. She invited female students to a “consciousness raising” session and asked about their experience in the workplace. “Every single one of these kids had already had an experience of having either been forced to quit a job or been fired because they had rejected the sexual overtures of a boss,” she said in a 2017 interview with On the Media host Brooke Gladstone.

Forley cast about intentionally for a term—a label—that would capture these shared experiences, and she settled on sexual harassment. She later wrote in the New York Times, “Working women immediately took up the phrase, which finally captured the sexual coercion they were experiencing daily. No longer did they have to explain to their friends and family that ‘he hit on me and wouldn’t take no for an answer, so I had to quit.’ What he did had a name.”

Above we talked about how habituation can help with phobias by normalizing the problematic. What Lin was doing, with the term sexual harassment, was the opposite: She wanted to problematize the normal. To reclassify the coercive treatment of women as something abnormal—to attach a stigma to it. She helped society awaken from problem blindness by giving the problem a name.

Problem blindness is as much a political phenomenon as a scientific one. We all participate in a perpetual negotiation about what we will sanction as a “problem” in our lives and in our world. These debates carry weight because once something is coded as a “problem,” it demands a solution. It creates an implied obligation. Sometimes these negotiations are with ourselves, as with the drinker who denies she has a “problem,” and sometimes with others close to us, as with a marital negotiation over whether to go to therapy. In society, there is a crowded marketplace of problems, all vying for a greater share of our resources and attention.

Sometimes we convince ourselves to address the wrong problems. In 1894, when more than 60,000 horses were transporting people daily around London, the Times predicted that, “In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.” Let’s leave aside for a moment the logistical implausibility of that particular nightmare. (How exactly would the 9th foot of manure have been added to the top of the pile?) Still, it was not a totally unreasonable fear: those 60,000 horses had an average daily “output” of 15 to 35 pounds of manure. At the first international urban planning meeting in New York City in 1898, the horse manure crisis was the talk of the conference. Fortunately, as we all know, the crisis never came. It was relieved by the advent of the automobile. (And, in turn, it’s now the car’s excretions—CO2 and particulates—that have caused us big problems.)

To see what it’s like to be on the inside of a present-day fight against problem blindness—a fight to awaken and mobilize the public against a problem—let’s trace the work of a Brazilian activist named Deborah Delage, whose awakening came when she gave birth to her daughter.

In August 2003, Delage, who was 37 weeks pregnant, came to see her obstetrician in the city of Santo André, São Paulo, for a routine checkup. When she arrived, her doctor said she was already in labor—she’d been having contractions so mild that she hadn’t taken them seriously. She was given a dose of oxytocin (often called Pitocin in the US), a drug that causes the muscles of the uterus to contract in order to speed up delivery. Twelve hours later, the doctor decided to perform a C-section, and Sofia was born. Both Deborah and Sofia were healthy and recovered well.

Delage was grateful for their health, but as she reflected on the experience, she grew increasingly unsettled. Why had they needed to accelerate the delivery? Why had her doctor seemed so eager to perform a C-section?

She found a discussion forum on the internet where mothers shared their experiences in childbirth, and many of their experiences mirrored hers: Despite wanting a natural childbirth, they had ended up receiving C-sections. Many of them, in fact, reported that their doctors had discouraged natural childbirth. “I realized that what had happened to me was also happening to other women across the country. It was happening to everybody,” she said.

She soon discovered statistics that backed up her intuition. C-section rates vary quite a bit around the world: 18% in Sweden, 25% in Spain, 26% in Canada, 30% in Germany, and 32% in the US for live births in 2016. In Brazil in 2014, the rate was 57%, one of the highest in the world. And in the country’s private health system, favored by wealthier Brazilians, a mind-boggling 84% of children were delivered via C-section.

A C-section is major surgery, of course—it has risks for both mother and child. It can be a lifesaver in certain situations. But at the rate of 84%, it’s clear that C-sections weren’t being used to escape risk or danger. They were being used to escape inconvenience. What caused the shift away from natural childbirth? It’s a much-debated topic both in Brazil and worldwide. For some women, a C-section is a matter of preference—you can plan for them. Some argue that the C-sections in Brazil’s private health system are a kind of status symbol. There are even stories about high-end private clinics in Brazil offering manicures and massages to go with the C-sections.

But the more convincing case is that doctors prefer C-sections. After all, C-sections can be scheduled in an orderly fashion, one after another. No need to work late hours or weekends or holidays. And the financial incentives strongly favored C-sections: Obstetricians could make much more money performing C-sections—which require maybe an hour or two of work—than they could delivering babies naturally, which might involve intermittent work over a 24-hour period.

Along with these structural explanations were cultural ones. “Childbirth is something that is primitive, ugly, nasty, inconvenient,” said Simone Diniz, commenting on doctors’ perceptions of natural birth, to the Atlantic. Diniz is a public health professor at the University of São Paulo. “There’s the idea that the experience of childbirth should be humiliating. When women are in labor, some doctors say, ‘When you were doing it, you didn’t complain, but now that you’re here, you cry.’ ”

That verbal abuse sounds like an extreme case—but according to Brazilian women, it’s not. In a survey of 1,626 women who’d given birth in Brazil, about a quarter of them said that the doctor made fun of their behavior or criticized them for their cries of pain. Over half of them said that, during the childbirth, they felt “inferior, vulnerable, or insecure.”

This was the reality Deborah Delage—who had felt misgivings about her own C-section—was discovering as she researched childbirth in Brazil. On the online forum she’d found, the mothers’ overlapping experiences reinforced their belief that something needed to change. Delage joined a new group called Parto do Princípio (roughly, “Principled Childbirth”), which had been founded to advocate for mothers.

In 2006, Parto do Princípio submitted a 35-page docu-

ment—half research paper, half manifesto—to the Federal Public Prosecutor, arguing that something had gone wrong with childbirth in Brazil. Women overwhelmingly reported that they wanted natural childbirth, the research showed, but they didn’t get it. They got C-sections instead. And as a result, the health of both mothers and babies suffered. The paper explained both the systemic causes of the problem and offered a set of recommendations for the health system.

Parto do Princípio won converts within the government, including Jacqueline Torres, an obstetric nurse and maternal health expert who worked at the ANS, Brazil’s regulator for private health insurance. Torres searched the country for people who had shifted the odds back in favor of natural childbirth, and eventually she came across Dr. Paulo Borem.

Borem was working on a pilot project in Jaboticabal—a town about 200 miles north of São Paulo—to increase the rate of natural birth using continuous improvement methods. It had been hard to find a partner for the project. At the first place he’d visited with his idea, he said, “They laughed at me. They said, ‘This is ridiculous. The women want C-sections. The doctors want them. There’s nothing wrong.’ ” (This is a perfect articulation of problem blindness.)

But he found a local hospital that was receptive to change. “The doctors told me they want to change,” he said. “They thought they were sending too many newborns to the NICU. It was disturbing for them.” Babies delivered via C-section are more frequently sent to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) after birth, often due to breathing problems that come from being born before full term.

When Dr. Borem started the project, the rate of natural childbirth at the hospital was 3%. “The system was designed to produce C-sections,” he said. So he and his collaborators started tweaking the system. Doctors were forbidden to schedule an elective C-section before 40 weeks; the norm had been 37 weeks. They were put into shifts; if a baby was delivered during a doctor’s shift, she would handle it—otherwise, another doctor would take care of it. (This was a break from the tradition of a doctor always delivering her patient’s baby, which the use of C-sections made easier.) Obstetric nurses were matched with patients to provide continuity through the delivery. And incentives were adjusted to make sure doctors’ incomes did not suffer.

Nine months later, the rate of natural childbirth had shot up to 40%.

When Torres from the ANS discovered Dr. Borem’s work, she knew she’d found a formula that might work nationwide. In 2015, the ANS launched a major project—Project Parto Adequado (the Adequate Birth Project)—to scale the work of Dr. Borem and his team in Jaboticabal. During the first 18-month phase of the project, which included 35 hospitals, the rate of vaginal delivery increased from 20% to 37.5%. Twelve of the hospitals showed a significant decrease in NICU admissions. In sum, at least 10,000 C-sections were avoided. The next phase of the project, with over three times as many hospitals, began in 2017. Pedro Delgado, a leader at one of the project’s partner organizations, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, said, “The results of phase 1 offer hope for what is possible in Brazil, and as importantly, in several other countries with similar rates across the globe such as Egypt, Dominican Republic, and Turkey.”

There is still a long way to go—the work to date is covering only a tiny fraction of Brazil’s 6,000+ hospitals. Nevertheless, there are signs that the health system is ready to change. Where initially Dr. Borem’s idea was met with mockery, there is now a waiting list of hospitals ready to embrace the project. Dr. Rita Sanchez, an obstetrician and the coordinator of Project Parto Adequado in a participating hospital, said that the campaign struck a chord with her: “We stopped and realized that the number of C-sections was too high,” she said. “Much higher than 20, 30 years ago. So we started questioning why and how we got to that point. And I realized that I wasn’t even informing my own patients about the risks of a C-section and the benefits of vaginal labor. We, the doctors, didn’t see the system changing.”

The escape from problem blindness begins with the shock of awareness that you’ve come to treat the abnormal as normal. Wait, why did I feel pressured to get a C-section? Wait, why have we come to accept a 52% high school graduation rate? The seed of improvement is dissatisfaction.

Next comes a search for community: Do other people feel this way? (Delage: I realized that what had happened to me was also happening to other women across the country. Forley on “sexual harassment”: Working women immediately took up the phrase, which finally captured the sexual coercion they were experiencing daily.) And with that recognition—that this phenomenon is a problem and we see it the same way—comes strength.

Something remarkable often happens next: People voluntarily hold themselves responsible for fixing problems they did not create. A journalist makes the choice to fight on behalf of the millions of women enduring sexual harassment. A woman pressured into a C-section becomes a champion for thousands of other mothers she’ll never meet.

The upstream advocate concludes: I was not the one who created this problem. But I will be the one to fix it. That shift in ownership—and its consequences—is what we will analyze next.

I. The old warnings about correlation not equaling causation apply here. There was no guarantee that improving freshmen’s FOT scores would boost the graduation rates. But there were good reasons to believe the two were linked causally, and of course they were tracking their efforts so that they could prove it.