1.

‘I’ll always have a clear memory of it because it happened so simply and without fuss.’

(‘House Taken Over’ by Julio Cortázar, tr. Paul Blackburn)

I hope I haven’t wasted this quotation by using it now.

2.

Then we woke up.

She smiled.

We got out of the car and stood leaning against the bonnet. Eating the last of our supplies – half a packet of biscuits, 3 peaches and the water – we decided that the prison sign was deterrent enough. We wouldn’t go on.

The sun was low and the long shadow of the car met ours out across the vast scrubland. I saw in this projection, in this combination of our shadows and that of the car, a cat’s head. We wondered what our cat might have been doing in that moment.

While she, sitting on the bonnet, ate the last biscuit, I put the key in the ignition; the needle on the petrol gauge swung to just past the reserve tank. I turned the engine on. At the sound of the exhaust a number of small birds shot up out of the bushes, lurching a little way through the air, like they had ballast in their feet, before landing once more. I revved the engine a little to warm it. She, still outside the car, hiked up her skirt, took off her knickers and took another pair out of the back. She flung the used ones away and they caught on the tapestry of the bushes, where we left them hanging.

3.

We made our way along now-familiar roads, and after 3 hours came to the main road. A Shell garage soon appeared. We filled the tank and had some breakfast in the cafeteria, decaf coffees, croissants and some very strangely branded mineral water. We sat at a table by the door and watched a large number of trucks drive by. Freezer trucks, trucks transporting lumber and sand, others transporting we didn’t know what, and still others transporting things we would never have imagined could be transported: an entire three-storey brick building drifted past at one point. She wondered aloud if the people who lived in it were inside.

We noticed that the truck drivers wore shirts, but then when they got out you saw that the only thing covering their hairy legs were their underpants, Y-fronts to be precise, all of them wore Y-fronts. We laughed quite a lot at this.

4.

It is quite clear that the problem of slums is mostly deeply ingrained – not only permitted but promoted by the authorities – in campsites. The only time we had ever set foot in one was in northern Italy, years earlier, having failed to find a hotel one time. We stayed for a night, and swore never to do so again.

So I was surprised when, having driven a little further, she suggested we stop at one. She didn’t go into her reasoning.

‘Look,’ she merely said, and pointed at the sign.

I hung an instinctive right. The fact that I didn’t object also seemed strange.

5.

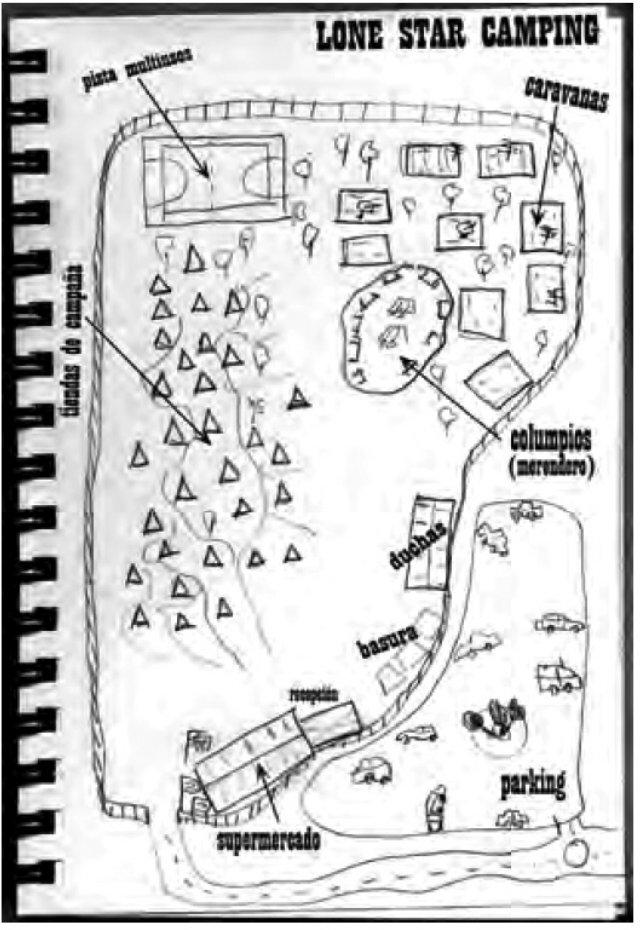

The campsite conformed more or less to everyone’s idea of a campsite, thus demonstrating that thought and nature are one. There was a shower area, tree area, tent area, caravan area, reception and small shop.

A sketch I did at the time gives a clearer idea:

6.

We hired a caravan at the edge of the property (see sketch). It was beige and had a dining table that folded out into a bed.

There was a family staying in the caravan on our right, the son cried over the tiniest thing. On our left was a hippie couple with dreads – they had a couple of imitation-African drums and weren’t afraid to use them. Across from us was an empty caravan, and behind us a valley and then a stretch of arable farmland.

Days passed.

She would go down to the beach in the early morning and, when it started to fill up, come back for breakfast; I’d just be waking. After that I would sit in the caravan reading and jotting things down at the folding table, and she’d go outside to sunbathe and watch the clouds; later on she’d go to the shop for supplies, always coming back with a new batch of knickers too, fearing future shortages. We’d have a simple lunch, and after that she’d go inside for a lie-down while I, so as not to wake her, took a turn outside, writing and watching the clouds; I’d recently been having difficulty discerning any shapes in them. Meanwhile, the clean knickers continued to pile up under the bed-table.

The caravans were arranged on a grid that created an impressive concentration of private spaces; each caravan came to be a substance made of chemically pure solitude. A person’s solitude is an almost impossible thing to penetrate, and even more so that of a caravan with multiple people inside it. Tribes, pills of different colours.

Sometimes I’d also fall asleep, glass of wine in hand, as she snored away inside. She’d wake me when the sun was going down and we’d go for a swim together; by now the beach would be all but empty and anyone still down there became mere silhouettes, fragments of charcoal, not hot but not cold, either, products of the day’s conflagration.

We sometimes sat on the sand and had sandwiches for dinner, washing them down with wine from a flask she bought in the souvenir shop; other nights we’d go back to the caravan and light the barbecue. She’d go to bed early and I’d stay up with the little battery-powered TV, staring into the screen until the test card came on. There was a programme presented by Rafaella Carrà, the ever-youthful talkshow goddess, that I particularly liked.

On one of those nights I overheard a conversation in the adjacent caravan. The father was telling the mother and son something he’d heard about a writer who, having spent years trying to write a novel, was now in hospital, very gravely ill because he’d spent the previous 2 years gradually ingesting his computer, little by little. He broke off pieces and sprinkled them on salads, stewed the larger bits with lentils. The father said he’d been told that the writer had justified his behaviour by pointing out that, if the success of other writers lay inside the machine, in the PC, if those other writers extracted their raw material from those inner workings, which contained both complete lexicons and the mysterious mechanism of their combinations, perhaps this was a way for him to perform – inside himself – the miracle of a perfect recombination of words. I heard the mother and son laughing at the paterfamilias for being so gullible.

But I believed him.

7.

I was motivated to sit outside in the afternoons reading and writing by the prospect of not reading and not writing: the idea of having an intention and then changing course, a practice in deviation; of accessing something toy-like in scale.

I once read a line in a Thomas Bernhard book about a character lying in bed with his extremities ‘oriented towards infinity’. I thought about that a lot, sitting there in my chair. I shut my eyes and shifted my body around, with the idea that via this continual radar-like rotation of my limbs I would hit upon the orientation towards infinity; I was bound to feel a tug on my arms and legs when I did.

8.

One morning she spent longer down at the beach than usual. I grew tired of waiting and erected the plastic table outside. I sat down on one side. Not at the head of the table, not at its rear but, as I say, on one side which meant it was like this: the open caravan door, then the table, then me; a very good composition, in my view. I lit a Lucky Strike, took out the coffee pot, sat down again.

Purely for the game of it, I made myself focus on the sounds of the campsite and nothing else. I didn’t shut my eyes, but I did focus. Out of that mélange of noises, separate layers of sound began to emerge, horizontal layers, vertical strips of sound, weighty conglomerates of sounds, weightless sound bubbles, sound-stars that flared for 1 nanosecond and then fell dark, and I also heard the rustle or crackle of leaves though no leaves were being stepped on or burned, the sound of a fork being dropped onto a table a few caravans away, a bird pecking at a peach stone, a baby saying what sounded like ‘mamma’, the straining of the wire bearing the Italian flag outside reception, the rustle of a bag of maggots in the heat of the shop, that’s all I remember. I discerned the unique and singular cosmos comprised by the campsite; by any campsite.

I had an idea.

The idea was to go wandering among the tents, bungalows and caravans or into the shop with a camera, and to ask anyone I came across (chosen at random) what made them choose this campsite, what their favourite sound in the campsite was, what the source of the sound was, then get them to draw a map of how to get to this place from wherever we happened to have met, and suggest that we both go there, to the source of the sound, and ask if they’d let me take a photo of them there, a photo I’d then call, for example, ‘Photo of the sound of a tree,’ or ‘Photo of the sound of my window.’ I’d make a catalogue from the results: on the right-hand page, the photo, and on the left the map drawn by the kind volunteer, and at the bottom of both pages a description of the event, the person’s details and their reason for choosing this spot over all others. The result would be a ‘cartography of the sounds in a campsite’.

Sitting by the table, I turned the thought over. A campsite could really be full of marvels, from the vague symmetry of the squares on a tablecloth to a pineapple with inscriptions carved into it. Or the rubbish area, with its constantly evolving flora and fauna, which made for a continually altered panorama.

Really, the campsite was the ideal place to carry out this experiment: it had the optimum concentration of people per m2, each with their corresponding planets and satellites.

I took the camera out, put the battery on to charge, and went to the shop to buy some blank paper and a couple of pencils.

I never understand why people come up with ideas and then don’t follow through on them. It’s criminal.

It was 2 p.m. by the time she got back. She’d been held up in the shop because they didn’t have any knickers when she arrived, but the delivery van was on its way; she decided to wait rather than having to go back again later on.

Then we made an omelette. As I peeled the potatoes and beat the eggs, and she fried everything in the pan, I told her my sound-photo idea. She liked it. We dressed the salad.

9.

In chronological order:

1) ‘Maybe the God we see, the God who calls the daily shots, is merely a subGod. Maybe there’s a God above this subGod who’s busy for a few God minutes with something else, and will be right back; and when he gets back will take the subGod by the ear and say: Now look. Look at that fat man. What did he ever do to you? Wasn’t he humble enough? Didn’t he endure enough abuse for a thousand men? Weren’t the simplest tasks hard? Didn’t you sense him craving affection? Were you unaware that his days unravelled as one long bad dream?’ (George Saunders, ‘The 400-Pound CEO’, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline)

2) ‘Dead-heading: the elimination of all branch-ends in order to rejuvenate the plant, prompting it to send out new shoots, which will later be cut too, following the usual procedure.’ (Fausta Mainardi, Illustrated Guide to Pruning)

3) ‘The following would be a sure recipe for a great Big Brother-like TV show: each week the contestants move to a different island on which the rules have been decided by the writings of a certain philosopher. In “Spinoza Week” they would have to find God in all things… In “Nietzsche Week” the contestants would be divided into children, lions and camels, and would have to learn to fly. In “Kierkegaard Week” they would learn to problem-solve through prayer.’ (Juan Bonilla, Chimera)

4) ‘Picture in your mind’s eye the sandpit divided in half with black sand on one side and white sand on the other. We take a child and have him run hundreds of times clockwise in the pit until the sand gets mixed and begins to turn grey; after that we have him run anticlockwise, but the result will not be a restoration of the original division but a greater degree of greyness and an increase of entropy.’ (Robert Smithson, A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey)

5) ‘A driver 30 years ago could maintain a sense of orientation in space. At the simple crossroads a little sign with an arrow confirmed what was obvious. One knew where one was. When the crossroads becomes a cloverleaf, one must turn right to turn left… But the driver has no time to ponder paradoxical subtleties within a dangerous, sinuous maze. She or he relies on signs for guidance – enormous signs in vast spaces at high speeds.’ (Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, Robert Venturi, Learning from Las Vegas.)

Eventually, once the campsite had consumed almost one month of our lives, we left. The last was:

‘All rights reserved. Any reproduction of this campsite, or partial or complete allusion to it, is prohibited, whether by mechanical means, chemical, photo-mechanical or electronic, including life-size reproductions and smaller-scale reproductions. The campsite will not return to its guests used electricity and water, nor will it enter into correspondence. The campsite will not necessarily share the opinions, or the lifestyles, of its clients after their departure.’ (The Management.)

As for the sound-photo project, I didn’t do anything with it.

10.

In the days that followed, without straying far from the area we’d been exploring, we returned the car and hired another, a slightly larger Lancia. I can’t remember the model.

The weather stayed stormy, and once or twice we got caught out on beaches.

We carried on with our island excursions, quite haphazardly, and a couple of times had to sleep in the car again, but at no point, I’d like to stress, did we go very far from the main road. Most of the houses in the inhabited towns and villages were half-built, with the brickwork exposed. Any time a construction job was completed a tax was levied; this way they avoided it.

Other times we came across abandoned villages with their exact replicas built directly next to them. You would come by 2 signs welcoming you to 2 identical villages. Another kind of doubleness that we could not fathom.

We spent quite a lot of time eating Belgian chocolate ice cream in the petrol stations and laughing at the get-up of families on their way to the beach. We even bought a kind of Italian lottery ticket at one of the newspaper stands, a very basic scratch card with a limited number of combinations, which made your chances of winning relatively high. Using a €1 coin, she scratched out 3 castles and came up with 3 yellow bananas, which meant we’d won the €200 prize, which we decided to spend on a 1 July dinner – her birthday. We chose the best restaurant we could find in the guidebook. We rang ahead to reserve the table on the terrace, which was on the pavement itself. While she made the reservation, using a public phone in a shopping centre, I saw 2 one-armed men walk by.

11.

Doubtless we didn’t look very smart, and so the waiter did all he could throughout the meal to not look after us – small, subtle things at the very edge of acceptability. But the food: exquisite.

After dessert, she picked up her handbag and said:

‘I’m going to the bathroom.’

She was taking a while. I started to wonder. After all, she was the one with the money.

Then I saw her appear down the road, driving the car. She beckoned me, and when I went over she threw open the door and yanked me in by the shirt. We sped off.

‘They can fuck off,’ she said. ‘That so-called waiter can pay for us.’

I told her off. I was very annoyed. But not for long.

What joins couples together is not mutual affection, or the making of plans that turn out as hoped, or the sharing of a home each has partaken in the buying and decorating of, or the siring of children, or any of the things they talk about in novels or films. What unites couples is a shared sense of humour. However different 2 people may be, if they have the same sense of humour they’ll succeed as a couple.

It was strange but the thing I was writing, with no clear goal in mind, was starting to take form, like a living organism in my notebook. The pages in the notebook were squared, and it was spiral-bound. The squares were caravans and the spiral was the electric cable joining them together, providing them with power.

12.

One of the hotels we stayed in in one unremarkable town belonged to an elderly couple. Formerly someone’s home, it had been hastily converted into a hotel at some point, and the wallpaper was all loud colours and impossible patterns. The dining room still had traces of its former existence as a family living-dining room: books, big adventure-classics in a glass display cabinet that would once have been a drinks cabinet, a basket full of old sewing thread, a VHS player with a crochet cover on top, and I can’t remember what else.

The couple who owned it welcomed us when we arrived; they had previously lived in Naples before retiring to Sardinia. We found this out because the husband, as soon as he set eyes on us, began asking questions, which meant that after 4 days there, without becoming intimate, we had got to know each other a little.

Our room was small but had some nice touches, like the double-glazed window, 2 toilets instead of one, and a crucifix over the bed featuring a Jesus with a comical expression. I also liked the doorknobs, they were masterfully done. They looked like pears.

The owners were often there when we went down to eat, so from the first day they suggested we join them at their table. We were the only guests who, like them, ate supper late.

On our third day they told us a little about their life together, a fairly unremarkable life. They got the photo albums out. Many of the photos were of the two of them together. Photos of unexceptional beach outings, photos of family get-togethers, dancing at weddings, etc., but, in all of them, she had no head: it had been cut out, chopped off. Seeing our surprise, he explained that it wasn’t his current wife but his previous one, and that she had died of cervical cancer in 1993.

‘When we got married,’ the current wife hurried to point out, ‘I thought the most courteous thing would be to take a pair of scissors to the photos, and he actually went and got them for me from the stationers.’

They clasped hands, squeezing fingers together, and I had thoughts of two balled-up maps, and the routes they contained becoming intertwined, confused. I looked at one of the photos of the deceased headless lady dancing a waltz with the man who was at that moment beside me. The headless lady had a hand on his shoulder and the other aloft, holding his hand; their hands were also clasped, fingers intertwined. An action performed with such force that it made me feel the exact same feeling that someone would experience as they tried to come back to life through a photo.

In bed that night we talked about this until very late.

13.

Tired of eating pasta and sheep, we turned to the Cooking with your Car Compendium by Steve Hunt, an American chef who, according to the blurb, had a shack in Brooklyn called Steve’s Restaurant, so we found a supermarket and bought some chicken breasts and potatoes to cook on the Lancia’s engine as we drove around. We did the marinating in the hotel room.

Ditches are an excellent place to have a picnic, and one thing the island had a lot of was ditches.

I would step on the accelerator and she would sing along, in snatches, to the CDs we had playing constantly in the car. We saw a field, and that we had driven the requisite cooking distance, 120 kilometres, for the chicken and potatoes, according to the Cooking with your Car Compendium by Steve Hunt, so we pulled over and took the food off the engine, all of it securely wrapped in tinfoil. We also took a few tomatoes (uncooked) to nibble on.

We ate our fill and it struck me she and I were a cassette tape, one that had been altered and manipulated, and that one day someone would find it in a ditch somewhere. I don’t know why it was a ditch I thought about and not a pavement, or a crate or an alleyway. But it was a ditch that I thought about.

14.

But the true space-within-a-space affecting us was a different one.

The dark space contained in a guitar case which in turn was contained inside a car boot, also dark.

We did not open the car boot again.

We went around with our suitcases in the back seat, which meant we couldn’t leave the car unattended for very long in case thieves should be attracted by the wares.

It could have been inertia that made us so determined to keep the boot shut, though, because I think we’d both lost faith in the Project by this point. Sometimes projects grow larger the more you try to keep them at arm’s length, and the more you try not to think about them; you distance yourself, but the metaphor does its job.

15.

While remaining within or close to the touristy part of the island, we spent a few days in a city which, according to the 2005 census, had 70,000 inhabitants. To find ourselves walking on pavements, to find shops we could go into, verifying for ourselves once more the wondrous thing that is spending money, did us more good than we’d expected.

In every shop we went into she would elevate the act of buying into a truly sophisticated system of codes and signs. I envied the way she handled the summer dresses, which were hung in series, cold from the air conditioning. I shuddered to think of this coldness as being to do with bodily absence.

The perfection of a city lies in it being a cosmos unto itself. Everything’s there. As it is on the grid of state-owned motorways. Yes, you can live in a city and never have to leave, yes, you can have the sensation that all life’s environments are there – being created and reproduced as well as extinguished. And any that are not, it doesn’t matter, the city invents them.

I bought a replica of a shirt worn by Steve McQueen in a motor-racing movie.

The countryside, on the other hand, is an open space, not a cosmos in and of itself. You can be okay there for a while, yes, but at some point the feeling will arise that something’s missing. We discussed it: maybe this was what had made us criss-cross the island, the largely rural island – maybe we’d been looking for something. Coming to the city, it suddenly seemed our search had ended.

We were in a shopping area at one point and, looking down, saw a mound of shotgun cartridges at the bottom of a drain.

She told me a story from her childhood concerning cartridges and shotguns.

16.

I have a tendency to neglect important details.

I’m reminded of a very hot day, possibly the hottest that summer, when we were still at the campsite, and seeing a middle-aged man sitting in a chair on a small area of dry earth, near the fence – not an ounce of shade to be found. I was out with my camera, searching. When I passed him, he asked if I had any water. I immediately recognized him: I’d seen him out jogging a few times.

As he gulped down the water, I looked at all the clothes he had on: wool jumpers, boots, a special, highly waterproof jacket for bivouacking under.

‘Aren’t you hot?’

I saw sadness in his eyes as he looked up at me, such sadness that it actually made his eyes look heavy, almost ovoid. He was unable to produce sweat, he said; it was his great hope to be able to sweat. Never in his life had he produced an ounce of sweat, and that was why he went out running, and why he let the sun beat down on his body.

‘I want to be a normal person, friend,’ he said, handing back the bottle. ‘I want to be normal, but it’s impossible. My friends call me “plastic man”, “unreal man”, or just “nothing man”. I try and compensate for my unrealness with food. I eat so, so much, I get fat,’ – he rubbed his belly – ‘because what I want is to be in the world, and for people to notice me. Sometimes I manage to forget I don’t have any water in my body, and then I’m happy, but sooner or later the truth of my situation comes back to me.’

He tried to stand up, and in doing so nearly fell down. He was woozy. His thin legs could not bear his body mass.

He should smoke, I said, not eat. We’re made up of 70% water, 30% smoke, I said, this is the perfect balance, bearing in mind that tobacco makes you thirsty all the time, so you end up drinking a lot of water. The whole 50% water, 50% fat thing was old news, I told him, it didn’t work: water and fat don’t mix, friend. Don’t eat, smoke! I said.

‘So you’re saying if I smoke, my body will be 70% water again?’ For a brief second, an ounce of happiness had entered his face.

‘Of course,’ I said. ‘That’s the law.’

‘Thank you,’ he said, hugging me. ‘I’ll give it a go.’

The hug lasted a few seconds. In spite of his roundness he was a dry stick, the driest thing I’ve ever been in contact with; he more or less crackled.

‘That’s that then,’ I said. ‘Would you mind telling me what your favourite sound is in the campsite, and could I also get you to draw me a picture of how to get there, and could I take a photo of you in that place?’

He stood thinking about it, for long enough that I was forced to add:

‘Do you not want to? Doesn’t matter if not.’

‘Oh,’ he said, hiking up the waistband on his tracksuit trousers, ‘not at all. I’m just thinking.’

He remained in standby mode, eyes twisted skywards, and then suddenly:

‘The thing is, my favourite sound isn’t anywhere in particular, so you can’t take a photo of it.’

‘Really?’ I said.

He knelt down, put his right ear to the ground, and moved around like that in a small circle, probing the earth with his ear. The waistband of his trousers slipped down to reveal the top of his buttocks. He scoured the dry portion of earth like this, on all fours, until he came to some grass where the tent area began. Stopping every now and then he’d straighten up and take a breath, before putting his ear to the ground again. Soon:

‘I think I can hear it.’

He stopped every now and then, finger to lips. I’d stop too, wouldn’t move a muscle. Then he’d beckon me with the same finger and we’d set off again. At some point he stopped, a eureka expression on his face:

‘Here!’ he said. ‘It’s here!’

I stood quietly, waiting.

‘The water down in the drains,’ he said, ‘underground – that’s the most beautiful sound there is.’

He got to his feet, and I could see he was welling up again:

‘If I just had a water network like this inside my body… Come on, let’s follow it.’

‘But you only need to find a tap and the sound would be there,’ I said. ‘You don’t need to go searching around for it.’

‘It isn’t the same. Taps, fountains, they don’t interest me: they’re outside. What I miss are those pipes inside my body. That “inner hum” – you surely know what I mean – some people call it the soul. Now, get a stick, would you, and dig a line in the sand. I’ll tell you where.’

I picked up a branch, he got down like a tracker again, and I went along marking the alleged water course. Soon enough I had marked out a labyrinth, only one with neither beginning nor centre.

‘This isn’t right,’ I said. ‘Drains have to lead somewhere, they have to start somewhere too, and there has to be a base point with a siphon and so on. This isn’t right.’

Hours went by, and I knew she’d be waiting for me to come back for dinner. I left the man, his ear still to the ground, and in his left hand a Smeraldina mineral water propaganda pen. He went on working that increasingly convoluted furrow.

17.

A day came when the monotony began to seep out through some gap or other in the Lancia. Gradually all conversation between us ceased. Not for nothing, since there was nothing to say. It was as though the two of us were one now, one so familiar with itself that silence is its natural way of interacting with things. Most of the time, when it’s like this, you don’t notice yourself. You pick up the phone and there’s no one there, for the simple reason that you’ve called yourself.

There were times when I wrote in my squared, spiral-bound notebook and it seemed like she was the one doing the writing.

One day our water ran out, it was a Sunday and all the village shops were shut. We were a good day’s drive from anywhere very populated. It was afternoon by the time we reached a petrol station. I sank myself, literally, under the tap in the toilets, which was a first-generation mixer tap. This led me to think about the fact that, since more or less the beginning of the 1980s, all taps have been mixer taps, i.e. not with one hot and one cold tap, but with a single central channel in which the water mixes, and a single handle. This shift came about just as modernity was segueing into postmodernity, the end-of-history moment, no more left/right ideologies, the time when a way of life arose in which everything was mixed together, a perfect block (or sphere) in which no direction (or vector) was privileged over any other and beyond which nothing(ness) lies (all is emptiness).

Couples usually strive to create their own self-contained spaces – self-contained as in nothing beyond them seems to exist.

The perfect couple is the mixer-tap couple.

18.

One day we came to a small village on a small island to the south of Sardinia.

We drove around looking for somewhere to park and the impression we formed was of somewhere strikingly similar to a village in Portugal on the Atlantic seaboard. It was almost the exact double of a port in the Azores I’d read a newspaper article about by a writer called Vila-Matas, I said. We went into a bar-pizzeria for something to eat, to watch the ships coming in, to watch bits of newspaper blowing around between the feet of passersby, to nothing, because all conversation between us had ceased. There was a neon sign on the door with a ship, much like the one in Moby-Dick, in a storm. A waitress with a very pasty complexion came over.

My mobile phone vibrated in my pocket.

19.

A few days later she said:

‘What would happen if you were in your villa one day, say a Sunday, and you went out to get your post, and the wind blew the door shut, and you’d left your key inside, and you’re there in your pyjamas, nothing on your feet, and you find yourself looking in at your coffee pot, the living room table with the little porcelain statue on it, the photo of the cat on the shelves, the books you left open on the floor beside your table, where your Mac is, messages flashing up on Messenger, your coffee cup on the draining board, the bin overflowing with Coke cans, and it struck you you’d been afforded a view of your life without you in it? What would happen?’

‘I’d smash the glass,’ I said.

‘Yeah, OK, but what else?’

I said nothing for a few seconds, then:

‘OK, I don’t know if I’d have the guts. For that kind of “return” to myself.’

The same day, she bought a Kinder Surprise, didn’t eat the egg, just broke it with the same careful self-absorption as a thief smashing a window, handing me the chocolate to eat, which I did, in a professional sort of way, the way you see mother-apes place bananas into their babies’ mouths after peeling them. She got the cut-and-paste truck from inside. The island seemed to have awoken a sudden interest in her for trucks. I had a thought about a cassette tape and wrote down the following:

‘There is a before and after in the history of humankind: the moment of the emergence of the cassette tape as a consumer product, and with it the possibility of cutting and pasting, and mixing and changing tracks.’

This was immediately followed by the thought – I’d had it before – about the two of us on or in a cassette tape, and that cassette tape being dropped in a ditch.

20.

I felt tired one day and she, for the first time, took the wheel; I lay down in the back, leaning my head on her bag of knickers. The implicit order in these white undergarments, the way they were perfectly stacked, their smell of industrial ironing – all of this felt peaceful to me. A mineral world. I shut my eyes.

When an object moves forward at a constant rate, and you are inside it, you feel nothing: Galileo’s principle of relativity means you are as though stationary. But upon acceleration or deceleration, the body registers the change, and then, if you are asleep, you wake.

This was what woke me, a slowing-down, a subtle braking, similar to the fluctuations of a dream. I opened my eyes. Suddenly everything was quiet.

‘I saw it in the distance,’ she said from the driver’s seat, speaking the words slowly, as though to herself.

I opened my eyes properly and, still lying down, saw a large yellow sign with black letters through the rear window:

ITALIAN REPUBLIC PRISON. NO ENTRY

I sat up abruptly. She seemed in a state of shock. She couldn’t explain what had happened:

‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘I got lost, I don’t know how I’ve managed to bring us back here again. I could’ve sworn I’d never seen that road before.’

I didn’t get annoyed with her, it wasn’t the end of the world, but I’ll admit the situation did make me uncomfortable. I had slept, and my deactivation of the world hadn’t in this case had a repairing effect. There, hanging from a bush, was the pair of knickers she’d thrown away 6 weeks earlier, now with holes in them from the nibblings of small animals.

I’m of the view that when life presents you with a line that turns out to be a curve, a pure curve – that is, when one comes back to the exact place one set out from – it means there were two possibilities in that place, and you chose the wrong one, the one that winnows out the arbitrary from life, sending it tumbling into an abstract deterministic bubble, a stable attractor: this is the witchery of stability, a spell that has to be broken. This is what led me to say we should carry on to the prison this time.

She didn’t need convincing.

21.

The road that unfolded before us was no different to some of the ones we’d seen a few months before. The tufts of grass grew sideways, from which I deduced it was a place of constant winds. I took the wheel.

A little over half an hour on, we spied a quadrangular building of indeterminate size. There was a high stone wall with an overhanging roof and watchtowers at every corner. The entire complex was surrounded by large rolls of barbed wire in place of fences.

It was a little before noon.

We drew closer, passing what appeared to be disused pillboxes on either side. Seagulls stood on these, looking south-west.

The road didn’t go past the prison as expected, but stopped outside it, directly in front of the first of 3 tall, gated fences.

And we wouldn’t have gone through even the first of these had we not seen, on the final one, a sign. On a board positioned symmetrically between two watchtowers, someone had graffitied the words:

SING-SING

ECOTOURISM

We drove on, in first gear. The grass grew very high in a kind of no-man’s-land between the rolls of barbed wire, which themselves stood at least twice as tall as any person. We came through the last of the gates, which was set into the stone wall, and came into a courtyard that must once have been the recreation yard but had now been turned into a garden, 75x75m2. The soundtrack from Breakfast at Tiffany’s was playing somewhere – a low, trickling sound, in a version saturated with violins. There were lawns intersected by gravel paths and well-tended hedges. The trees, all of the same variety, one I didn’t recognize, were scattered here and there, and gave shade to a small fountain in the middle. Each of the four walls, which were quite vertical, had a multitude of small, unbarred windows in neat, bitmap-like rows. Two small dogs were copulating beneath a tree.

We drove around the outside of the garden, staying in first, and came to a wooden portico door. There was a sign to one side, very new-looking, which read ‘Reception’ in Andale-Mono font. I pressed the buzzer.

When we entered, the man inside took a number of seconds to look up from whatever he was reading behind the counter. He took off his reading glasses, looked at us and said in a flat voice:

‘Welcome.’

The price seemed reasonable.

He showed us to our room.

22.

Investigating the grounds in their entirety, we found that the edifice was indeed built upon square foundations. The 4 sides of the aforementioned garden were formed by the 4 former prison wings. Each was set out over 3 floors and had a central passageway, 75 metres long, with the cells on either side; it was more like a central road than a central passageway, except it wasn’t open to the sky [it made me think of shopping centres]. The 2 upper floors were accessed via enclosed stairwells and gangways. There must have been over 1,000 rooms.

Ours was on the third floor and had a window that looked out over the interior garden; we could also see a little of the horizon. TV, double bed, shower, toilet, air conditioning and everything else one would expect of a 3-star eco-hotel. And the original metal cell door with the original sliding peephole. The ground, walls and lamps were spotless, they reminded you of an operating theatre. The bed and bedside tables, also made of metal, were bolted to the floor. We put our luggage down and I immediately went and splashed water on my face. There was a mirror: I looked tired. I didn’t feel tired but, as though pretending, my face looked tired. The hand towel, white, which I used to dab my face, bore no emblem or logo of any kind.

23.

Before dinner that night we sat at one of the cloister-garden tables drinking vermouth. He brought us the drinks himself, and his demeanour was distant but not cold, an attitude entirely different to that of other hoteliers we’d encountered on the island.

‘He reminds me of Kusturica, the film director, but older and grey,’ she said, stirring the ice cubes in her conical glass. ‘Pretty hot, wouldn’t you say?’

She was right.

We looked across the bitmap of square windows surrounding us on all sides; we had left the light on in our room. The sun had not yet set but it was dark in the rooms already.

It looked to me like it had once been a monastery, before an ecotourism place, and before a prison. I pointed this out. She agreed. We seemed suddenly to be agreeing about things.

We left our drinks half finished and got up to go for dinner. It would never have occurred to me to do so, but she, who sometimes bought pot plants for the terrace at home, and who occasionally even dreamed about TV-advert hydrangeas, ran her hand over the leaves of one of the immaculate hedges. She halted and, leaning down over the green mass, began prodding the leaves with delight. Turning to me, she said:

‘Fuck me, they’re plastic!’

She went over to a tree, and to another of the hedges, ran a hand over one of the lawns, the stones:

‘It’s all plastic! The whole garden!’

I ran my hand over the greenery, too, and she was right, what we had was 75x75m2 of faux foliage. It seemed none of it had been dusted in years, and, beneath this thick grey patina, it looked real.

Rather: it had become real.

When we came through the reception on our way to the eating area she picked up some tourist brochures and leaflets; she never read these, they just piled up in the car. I said something about the food maybe being plastic, too. She jabbed me with her elbow.

There was a large eating area with very long tables and benches. At one end of one of the tables was a tablecloth with 2 places set facing one another. 10 metres along on the same table, at another tablecloth for 2, he was having his supper, alone. He was eating soup that smelled strongly like lamb. We seemed to be the only guests.

By process of elimination, we sat at the only unattended tablecloth. He got up without a word and went into the kitchens through aluminium swing doors that continued swinging open and shut, open and shut, almost as long as it took him to emerge once more bearing a platter of grilled vegetables and a carafe of red wine. His movements were slow. After serving us, he went back over and resumed eating.

The rest of the dinner transpired in a series of similar sequences, spaghetti Bolognese followed by very strong lamb stew and then fresh fruit. She and I would exchange brief glances, laughing to ourselves, or grimacing at the lighting, which looked like it had been taken from some shed for animal husbandry, or at the surface of the table, into which names, hearts, messages and pictures had been carved, as far along the tables as we could see; traces left by former prisoners.

24.

We did a number of different things in our first few days there: cleaning the car, sunbathing on the terrace, drinking vermouth, and me a little writing when I got tired of lounging around. She started becoming argumentative over the smallest things; suddenly the tiniest detail, the kind of thing no one would notice, became a source of conflict. She said this was a sure sign of her tiredness.

It was on the third night, going through to the eating area for supper, that we saw an extra place set alongside ours; we asked ourselves who the new guest might be. But the owner appeared a few minutes later, and sat down at this newly laid place, across from me and alongside her.

He was a lot friendlier than before.

We returned his greetings. Following that, not a word was spoken until the second course had begun, at which point he took out a cigarette and started rummaging around in his pockets, seemingly for a lighter he could not locate. After a few seconds she spontaneously said to me:

‘Pass me the igniter.’

Which I did. And she gave it to him. And he turned it over in his hands for a few moments. And lit his cigarette, looking directly into the flame. And handed it back to her, and when she went to put it in her pocket, I said:

‘Pass me the igniter.’

Which she did, and I lit a cigarette, and before I had time to put it back in my pocket, she said:

‘Hey, pass me the igniter.’

And I did and she took a Marlboro out of her bag and lit it, and was about to slot the lighter in with her cigarettes, but then he motioned for her to pass it over; his wasn’t smoking properly. And she handed it to him, and he relit his cigarette, and handed the lighter to her, and she again went to slot it into her pack of cigarettes, and I said:

‘Hey, pass me the igniter.’

And she passed it to me and I put it in my shirt pocket. Then he, looking at her and her alone – looking her in the eye – said:

‘Thanks.’ And burst out laughing.

Conversation ensued. Niceties to begin with: where we were from, what we did, and this was how we found out he was a collector of, and researcher into, old texts; he didn’t specify which era. And also how we learned that he had bought the old prison five years earlier, and that setting it up as an ecotourism place was an excuse to keep the world at enough of an arm’s length that he could dedicate himself to his true passion; his argument was the following:

‘Ecotourism is very well-subsidized here and, since the jail sign puts off any possible guests, I can pocket the subsidies and spend my time doing what I want.’

Pretty difficult to argue with, I thought.

At a certain point we told one another our names; he and I had the same name, it turned out, Agustín, a coincidence that set us off laughing again for a while.

We were surprised by the liveliness of his conversation and just how charming he was. We talked about books, and he threaded together stories and anecdotes that led off in all sorts of different directions. We listened carefully to everything he said, our only interruption being me occasionally asking if people wanted more wine, and filling the 3 glasses. She didn’t talk at all. Dinner ended, and after we had talked a while longer, he offered to show us round his living quarters and where he worked.

We followed him over to the door at the far end of the eating area and into what looked like an apartment.

His exact words were: ‘The prison governor used to live here.’

It consisted of several adjacent rooms, no passageways between them, and minimally furnished; you could almost say of them that the concept of decoration didn’t exist. On the chimney breast hung a row of miniature figures, Captain America, the Fantastic 4, and some other Marvel characters I can’t now remember, all made of toxic rubber. All of this he showed us quite hastily, as though it were a mere prologue to the place the mention of which made his eyes gleam: the studio.

We left the apartment through a back door and came into a kind of orchard, little-tended and surrounded by stone walls, which we had not laid eyes on until this point. 2 rows of globular lights had been strung across the middle, casting faint patches of colour onto the weed-choked path. At the far end stood a low stone gatehouse. He said nothing as we crossed the orchard, not even when the door to the gatehouse refused to open and he had to apply his shoulder. Then, with a kind of bow, he invited us to go in. She went first, he watching her intently.

Inside, the 4 walls were covered, literally, with books. Books seemingly old, new and everything in between, and in one corner, a glass table with metal legs bearing a laptop that was turned on. He told us that he spent entire days at this table consulting texts, archiving offprints, searching for traces of hugely valuable, supposedly lost books. I saw scattered around the place other seemingly antique objects, revolting figurines, half-assembled clocks, dried-out fountain pens, more Marvel superheroes, that kind of thing.

I can’t remember very much else about the night, except that we had quite a good time sitting in his leather chairs drinking a liqueur made from myrtle leaves.

Then, over the following 4 days, we didn’t see him at all.

25.

We’d get up in the morning and find that our breakfast had been placed on the same tablecloth, always the same place, along with a note saying ‘Busy today’; it was the same at lunch and dinner. The only sign of him was the music that seemed to be coming from his studio. Neapolitan songs, very loud. The sorts of classic songs we were familiar with from TV and movies. ‘’O sole mio’, that sort of thing.

We used this time to go on car trips in the area. The sea turned out to be 2km to the south. One afternoon, sitting on the beach, we saw something out at sea, what looked like an island with turrets of some kind projecting upwards into the sky. On another occasion we came to a very long beach which, instead of sand, was formed entirely of grains of rice; very worn white quartz of the same dimensions and ellipsoid shape as a grain of rice. What a thing it was to lie down in that paella – like waiting to be cooked.

26.

He emerged on the fifth day at lunch. He was beaming, said he’d made important progress in his research, cause for celebration. He didn’t tell us specifically what, but we supposed it must be something important – he did say he’d been struggling with it for 2 months, some spanner in the works, but didn’t go into details. He said, a few times, that if it came off it was going to be his most significant finding.

We retired early that night. We were worn out from the sun and walking. She went to bed but I went up to the rooftop terrace: it was a beautiful night, the moon nearly full. To one side stood the plastic garden, completely stationary, not the slightest movement of a single leaf, and on the other his studio: though I couldn’t see inside from where I was, light streamed out through the windows, and his music was audible too. I smoked a cigarette, contemplated the island we’d seen from the beach and its turrets, doubtless military in character, which were dotted with lights. After that I descended the metal stairwell, came back along the gangway, also metallic, and past the cell doors, some of which were shut but most of which stood ajar, and, reaching ours, got straight into bed. I thought of the square of light our window comprised, and of lighthouses guiding ships that go off course, of the click of the light switch that gives you a north, saving you from disorientation, and about the fact that there probably wasn’t anybody within a radius of several kilometres to see it. She lay breathing on my right. I turned out the light.

27.

A few days passed with no further sight of him, but now he’d stopped bothering to make us any food. He left badly-written notes to say we should go into the kitchens and help ourselves.

We started spending quite a lot of time in these kitchens. When you are away from home, you never have access to this particular, commonplace area. It’s comforting.

Stoves of an industrial kind, steel countertops, sealed-off store rooms here and there, like a library but for food.

The first time we went into the kitchens, the playful essence of childhood was rekindled, kind of, and we kissed, and envisaged playing out the clichéd scene of her trying to escape along the gangways, provoking a pursuer, only in the end to let herself be caught, and to let me do whatever I liked with her. It was silly, but for the first time in a long time I saw her laugh.

There was a heavy steel door to one side – the door to the cold storage room. We opened it. White icy smoke enveloped us. We could half-see a number of frozen lambs hanging from hooks. ‘Fuck me!’ she exclaimed. It didn’t affect me. There were also a number of pig heads that had been chopped up, to strangely beautiful effect; the snouts had been sliced straight down the middle, giving a view of the bizarre structure of the nasal cavities, which looked like fractals; I waited for them to defrost a little and took a photo. She made lunch. I threw the head onto the land behind the complex, it barely rolled.

28.

We were making breakfast one morning in the kitchens. The lamb stew was almost ready when he appeared. He pushed open the swing doors and said,

‘Anything for me?’

He looked dishevelled, and older, with several days’ worth of grey stubble.

The 3 of us ate our breakfast standing there, next to some aluminium, industrial-sized pans. We spent a long while chatting, any comment from us would prompt him to talk and talk; he said he was very happy. ‘Great progress,’ he declared, over and over.

He drank his coffee quickly, devoured the stewed lamb sandwich and went away again.

29.

I was woken by the sun one morning. We’d forgotten to close the shutters. She was still sound asleep, but I’d had trouble digesting the previous night’s supper and hadn’t gone to sleep until well into the early hours; I now felt heavy. I got up.

I don’t remember the exact time, but it would have been around 6 a.m. I washed my face and brushed my teeth, focusing particularly on my tongue and a place where I was starting to get a cavity. The towel was very dirty, I decided to go and get a clean one from another one of the cells.

There weren’t any towels in the room next to ours, or in the next one along, or in the next. I checked as many as eight rooms and then, out of simple curiosity, carried on walking along the gangway.

It made me feel slightly dizzy looking down through the grate flooring. Across the way, the gangway of the opposite ‘pavement’. You could poke your head out and look up at the floors above, and down at the road-like central corridor breaking off to left and right. I went along opening cell doors, all with the exact same metal door and sliding peephole. Inside, the cells were also all the same; a repetition I found obscurely exciting. I went down to the second floor and did the same again: opening the doors, going inside, looking around for a few seconds, thinking about the man who would one day have done time there, coming back out. And so on until I came to the central corridor, crossing and taking the steps on the far side, up to the cells across from ours. In a way, I thought, it was like the spot-the-difference game you got in newspapers, trying to find the 7 differences between the 2 apparently identical pictures. I went on opening and shutting doors. And found just the one difference: a typewriter on a bedside table in one of the cells. I opened the drawer and found a stack of unused A4 paper. On an impulse, I gathered up both the typewriter and the stack of paper and took them with me. It was precisely what I needed in order to type up my notes. And there was no way he’d notice the change; I’d never seen him anywhere near these rooms. Coming out of the cell, I saw that in our room, almost directly opposite, she had now got up. She got out of the shower, naked, and in that moment I had no regrets about having chosen her.

I went back. Typewriter under one arm, A4 paper under the other, and the white towel I had gone in search of slung over my shoulder.

Over the following days I shut myself in from dusk till dawn, typing up the scattered notes I had been making in my spiral notebook. She brought up my food at meal times.

30.

Though you normally have to pay a week up front in ecotourism places, we had been there for a long time and hadn’t been doing this. We’d lost track of exactly how long. With the help of a calendar in reception, we made it 18 days. I worked out how much we owed, and she waited for me downstairs as I went to our room to get the money.

As previously, to get to his studio you had to go through his quarters. As we were coming through the living room she sat down for a moment, looked around, then shut her eyes and sighed.

‘I feel like going home.’

I fingered the toxic-rubber Marvel figures on the chimney breast.

We went out into the orchard through the door he’d shown us, crossed beneath the swaying coloured bulbs and knocked on his door. The music stopped; after a few seconds he came to the door. The light inside gave a clear view of his face. She spoke first:

‘Hi, we’ve come to pay –’

‘Oh, good,’ he said cutting her off. ‘I could do with the money, actually. Come in.’

The place was messier than usual; there was a strong smell of stables.

We picked our way through chairs, books and piles of junk; there were numerous lamps placed here and there in the room, each casting its own little pool of light. We must both have seen it at the same time; we both stopped. On the floor, next to his worktable, there lay the case for a Gibson Les Paul, black, and inside it what we could see were all the necessaries for the Project, our Project.

‘Ah,’ he said without looking at us, ‘this is what I’ve been working on.’

Then, looking us each in the eye, he said:

‘It’s a project, an immense project. I’ve been so completely wrapped up in it, I’ve put aside my studies altogether.’

I couldn’t think of what to say; after a couple of seconds she spoke:

‘Where did you get it?’

‘Found it on the beach,’ he said. ‘The sea washed up this guitar case. But that’s all I can tell you, it’s a secret, as I say, something immense.’

I felt a sort of dizziness, a rush of blood that demanded the floodgates in my head be opened, I don’t know, I think I was on the verge of fainting – out of this cloud the question emerged, the question I asked out of pure intuition, and without knowing very well what kind of intuition, it couldn’t even be called a hunch or a premonition, it came from somewhere deeper and further off than hunches or premonitions:

‘What’s your name?’

With a surprised arch of the eyebrow, he said:

‘Agustín, you already know the answer to that question.’

‘No,’ I insisted. ‘Your full name.’

‘Agustín Fernández Mallo.’

When something is so dizzyingly superior to you, you turn docile, you simply go along with it. I lacked the courage to say anything. We walked out almost immediately. We forgot about paying.

31.

We stayed up all night, talking about how it was impossible that he should have known my name; when we arrived he hadn’t asked for any documentation and we hadn’t been made to sign a register. He must have read it in the notes inside the guitar case. There wasn’t any other way. But this was just the nerves talking, nerves and hasty logic; after a few minutes we conceded that there was no mention of my name on anything inside the guitar case either.

She started to panic – a panic modulated by my presence, but panic all the same. I just felt bewildered.

My view was that we couldn’t let him steal our Project; to me this was unconscionable. She just wanted to get away, get out of there straightaway, even if that meant giving up on the Project. I wouldn’t budge, and suggested, as a way of getting her onside, that we ought to wait until he left his studio, go inside, get the case and run; but it wasn’t clear to me. I felt both extremely angry and extremely curious, a combination that resulted in me wanting to stay put: to find out how much he had found out; to see how far he’d gone in assembling and comprehending the assortment of things inside the guitar case. To me there was no question of leaving.

I managed to convince her, before we went to bed, to stay on for a few days.

32.

We decided not to leave the room at all except for food. We’d go and fix something, and bring it back up as quickly as possible. I typed away, and the whip-cracks of every keystroke melded in the air with the strains of the Neapolitan songs. She was finding the whole thing difficult to bear.

Our paths crossed at one point. We were coming out of the kitchens and he was going in; he looked more like a car-parking attendant than an erudite bibliophile.

‘Goodness,’ he said. ‘Been a while. What are you two doing up there all day long?’

‘Working,’ I said without thinking.

‘Me too, me too. You should come by again one of these evenings, that’s when I take a break. We’ll have a drink.’

33.

I don’t know how she got it into her head to go there because she never gave much away, but one morning she was gone. We kept the cell door open and before I realized it, she’d vanished. She often went out to the gangway and sat at the edge with her legs dangling down, smoking and looking at the row of doors across from us. She said the echo of my typing was relaxing, that instead of a machine designed for typing it seemed to her like a machine for erasing, as though with every keystroke a fragment of everything she wished to forget had been erased. So involved in my writing was I, I simply didn’t notice her go.

I heard footsteps, someone running up the metal steps, first floor, second floor, third floor, and then the unmistakable sound of someone approaching at a run. She came in trembling, went over and sat down on the bed, I gave her water to drink and, still panting, she said she’d been down in the kitchens, and had had a strong impulse to go looking around his living quarters. She was nosing around knowing that as long as she could hear the music coming from the studio she was safe. After looking through the many photos in the chests of drawers, and the books in the library – all of them, curiously enough, cheap editions of noir novels – she opened a wardrobe and found, in a neat pile, all of her dirty knickers, all the knickers she had been throwing in the bin during our stay, a pile of very neatly folded dirty knickers; at that, she ran.

For me, the fact he had been rummaging around in our bin didn’t change things very much. For her, it was the last straw.

‘I’m leaving,’ she said. ‘If you’re coming, good, if not, that’s fine too.’

I couldn’t go. I couldn’t leave it like this, abandon the Project.

34.

We decided she’d take the car. Not that there was much of a decision to make as there wasn’t any other way out of there. We decided that when it came time for me to leave, I’d ask him to take me to the nearest village or town, and from there get a bus, or whatever there was, to the airport.

I don’t remember the exact date, but it was some time in early September. In the morning I went with her as far as the last barbed wire fence. We kissed. I stood watching the exhaust fumes until she was out of sight.

35.

I let a few days pass, but I had made up my mind: I was going to tell him exactly what it was he’d stumbled upon, and the enormous cost to us not just of coming up with the idea, but then of putting it in motion; that he had to give it all back to us, and that there was no way I was taking no for an answer.

And so, the week after she left, I went down to his studio one evening. I knocked on the door. I heard him turn down the music, and then he was at the door:

‘Well, well. I saw the car had gone, I thought you’d left without paying.’

He told me to come in.

We sat facing one another, and he said nothing as I told him the story, how it was that the Gibson case had fallen into his hands, I even went into details about the bar that resembled a bar in the Azores, the dock we had walked along, how we had thrown the guitar case into the sea; I went so far as to mention the dead cat; I laid it all out for him, followed by my demand: it was time for him to return these things to us.

When I had finished, he got up, poured himself some of the myrtle liqueur – I said I didn’t want any – and, without sitting back down, said,

‘I’m afraid that isn’t going to be possible. You, sir, are not the owner of this guitar case, or its contents, or this project. First of all, you say you’ve got the same name as me, Agustín Fernández Mallo. Well, I’m going to need proof of that. Either you are a madman, sir, or you are very barefaced.’

Patting my trouser pocket, I realized I hadn’t brought my wallet with me. In fact, I thought with a shudder, I’d left it in the glove compartment of the car; I had no way of proving my identity. My mobile phone was in the glove compartment too, I realized, meaning I also had no way of ringing anyone who could back up my story.

‘I see what’s happening here,’ he said with conviction. ‘Who are you trying to fool? I’m Agustín Fernández Mallo, and this is some bad joke. The contents of that guitar case belong to me.’

I got up and went over to his table – he came with me. Everything concerning our Project was there, and I was picking things up and turning them over – as much as he would allow. I pretended to compose myself, thinking I’d grab it all and run as soon as the chance arose, or at least snatch up the indispensable things, the things without which the Project could never get off the ground. I began acting interested, and I did actually feel curious about what he was planning to do with it all. Gradually I drew him in, until at one point he said,

‘Look, here it is.’

Extracting a sheaf of papers from a drawer, he handed it to me. 100 or so pieces of paper, typed up in a word processing-programme; I clenched them in my hands, I couldn’t believe this guy could have thought that the Project, our Project, consisted of coming up with a text, a simple text, the kind of thing any writer, even a quite ordinary writer, could have done. He clearly knew nothing, and certainly didn’t deserve to be the owner of that guitar case or the keys it contained to such a Project. While he poured himself another measure of the liqueur, I skimmed the first page:

Part I: Automatic Search Engine

True story, very significant too, a man returns to the deserted city of Pripyat, near Chernobyl, a place he and the rest of the populace fled following the nuclear reactor disaster 5 years before, walks the empty streets, which, like the perfectly preserved buildings, take him back to his life in the city, his efforts as a construction worker here in the 1970s were not for nothing, comes to his own street, scans the tower block for the windows of his former flat, surveying the exterior for a couple of seconds, 7 seconds, 15 seconds, 1 minute, before turning the camera around so that his face is in shot and saying, Not sure, not sure this is where my flat was, then gazes up at the forest of windows again and says, not to camera this time, I don’t know, it could be that one, or that one over there maybe, I just don’t know, and he doesn’t cry, doesn’t seem affected in any way, couldn’t even be said to seem particularly confused, this is an important story concerning the existence of likenesses between things, I could have stuck with this man, could have looked into his past, how he was living now, which patron saint’s day he was born on, his domestic dramas, the amount of millisieverts or gamma, alpha and beta radiation his organism had been subjected to in the past

I stopped, skipped a few pages and began reading again at random:

the same obsession that, we then found out, had its inception in Las Vegas, on those nights of mineral silence in which we had read a book called The Music of Chance by someone called Paul Auster before sparking up a Lucky Strike and listening to the sound of thousands of waiters mixing cocktails for thousands of people under the watchful lenses of thousands of CCTV cameras, yes, I mean to say that while we were watching all those films and TV series at home, eating that pizza and drinking that chilled white wine neither of us had the first idea what the other was planning, or about the immensity of the other’s incubation, a thing that was destined to change our lives, and all of this came out in our conversation that day in that bar on an island to the south of Sardinia that resembled a bar in the Azores, Strange, she said, that all this, all these things, can fit inside the case of a Gibson Les Paul, that something of such immensity can be reduced to a few cubic centimetres, to a

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I skipped straight to the end:

but I wasn’t thinking about any of this as I fell asleep that night in the Lancia with the final waking image of her breasts spilling from the overcoat, two fried-egg prints, a coincidence, maybe, I don’t know, I’m a great believer in coincidences, an American writer from the ’40s called Allen Ginsberg wrote the following at the age of 17: ‘I will be a genius of one kind or another, probably in literature,’ but he also said: ‘I’m a lost little boy, lost my way, looking for love’s matrix.’

At that point he snatched the pages from me, saying,

‘That’s enough. And by the way, I’m still waiting for you to pay me. Maybe when you do, you’ll let me know your real name too.’

Putting everything back inside the guitar case, he shut it, and then kicked it a short distance away, positioning it under a piece of furniture. He took the text and went off to the toilet, which was to one side of the room. When I heard the sound of his parabola of urine hitting the water, I unplugged his laptop from the wall, picked it up and ran; I failed to disconnect it from the small printer on one side, which fell to the floor, and I dragged it along behind me as well. I ran as fast as I could.

He didn’t run after me, he didn’t call out. Not a word.

36.

I shut myself in, and this time I did begin hammering at the keys non-stop – a defence mechanism, I guess. I couldn’t think, and I didn’t want to think. His Neapolitan songs carried on playing, and I couldn’t understand how he could have written all these things, how he could possibly know, not about these details so much, but rather about my life as a whole, because of course there was no way he could have found out all this information, everything in the text, from the contents of the guitar case; in the month we’d spent in the ecoprison, he simply couldn’t have learned all these things, some of which touched on events in my life years in the past. It was just impossible. To top it off, when I turned the laptop on to see if I could find any clues, it turned out to be empty; no user files, no folders whatsoever, whether containing text, image or sound, there weren’t even any programmes, nor any word-processing software – nothing. It was an empty brain, empty like mine was, I thought, identity-less, set up as if to prevent life from ever being written or constructed again. The only thing I found, some kind of seemingly macabre joke, was a succession of empty folders, one inside the other, named in sequence: Sing-Sing_1, Sing-Sing_2, Sing-Sing_3, Sing-Sing_4, etc., going all the way into the 200s, and effectively the most accurate representation possible of the infinite solitude inside an also infinite jail with a single man inside. I went along opening each of these in turn and, when I came to the last one, did find a piece of rudimentary image-processing software hidden inside. But what use was this? I now understood why he hadn’t bothered to follow me when I ran off with this pointless contraption.

I started having nightmares, and even on occasion woke up convinced that I had no identity, that I was the imposter, or, like in some cheap, straight-to-DVD movie, that it had all been a dream and since the day I’d been born I’d been dreaming his life, Agustín’s life. Gradually, and without realizing at first, any time he came to mind that was how I started thinking of him, as ‘Agustín’ – I began to designate myself as ‘I’, nothing more. In calmer moments I thought perhaps he might be a sorcerer, a seer, some prodigy of superlative genius, and that he was able to take the objects in the guitar case, our brain-children, and just by touching them, with a burst of some unknown energy, see everything that had happened in our lives, make them pass before his eyes like the frames in a film, and finally possess them. A hypothesis that got me nowhere. Looking around at the bed and the tables in my room, all of which were bolted down, I began to speculate about it being a cabin and the entire ecoprison part of an ocean liner now grounded on a desiccated seabed, formerly home to fish, seaweed, tides, ports, bars where the sailors pinned up messages for one another on a large corkboard that now also lay here, out on this hot tundra, formerly the very bottom of the sea; that those pieces of paper and the words that had gone to form those messages would now be dust, airborne molecules I was now breathing, as well as the molecules of the objects I touched and the green vegetables I was eating. Thoughts I found profoundly disturbing; a disturbance I could never get to go away.

I tried to work out some way of locking the room from the inside. I couldn’t just pile furniture up against it, everything being bolted down, so I removed 15 of the keys from the typewriter, levers and all, and jammed them between the door and the doorframe, like the bolts you get on domestic armoured doors. He’d still be able to get in if he tried, but never to catch me off-guard. It took me a long time to choose which letters to remove; it was a bit like removing part of the DNA that allowed me to write, survive. In the end I decided on the punctuation keys, the space bar and the accents, and when I’d used those up I had to sacrifice the X and the W too.

I felt a little calmer now, but after a few days I stopped writing, I was blocked, couldn’t do it any more; the reality of my situation became apparent: I was inside a prison cell, I had no means of transport, my personality had been usurped, and I had let myself lapse into a state of extreme laziness. All day, watching the TV and drinking water. Human beings can last approximately three months without food, but no more than three or four days without anything to drink. The proximity of the sea made the tap water slightly saline, so it was the closest thing you can get to survival serum. I also knew that lack of sleep would sooner kill a person than not eating, that you can lose your mind from not sleeping, and so I’d shut my eyes at night in an attempt to forget, but was never able to sleep more than an hour at a time. I’d get up, wash my face, and when I dried it the dirt that transferred onto the white towel made me think that it now had an emblem or a logo: that of the sheer ignominy I was being subjected to. When I looked in the mirror, I saw before me an aged twin.

I was gripped by a kind of Stockholm syndrome, I spent all day in front of the TV, taking in every single programme, test card to test card, and this put me in mind of my time as a student, the time that he, Agustín, had now consigned to those slanderous sheets of paper, the time when I’d started writing, when I used to go out at 9 p.m. for cigarettes and come back up feeling god-like, sitting down at the typewriter with the TV on mute in the background, a muted TV that, like now in this ecoprison, served the function of a landscape, of a train window you simultaneously look out of and do not, a way of passing the time until your journey comes to a sudden stop. I hoped, in the same way, this journey would also end. The days passed, everything stayed the same.

I had the idea of taking photos of the TV again – something I’d done in the past. Previously my attitude had been purely artistic, but I had different ideas now: I set down on paper any possible similarities between this prison, this ignominious situation, and anything else in the world, bearing witness to my time there via photos of the one place in which life still existed, the TV screen. If anything happened to me, here would be something someone might later find. I began taking photos of films, reality TV shows, game shows, news programmes, newsflashes, cartoons, everything, but the story of how we had come to that place, and everything concerning the journey, became my one obsession, and my goal now with these photos was altogether different: to recount, to the extent that it was possible, my life, as a way of regaining myself, of reconstructing my personality. I uploaded the photos directly from my camera to the stolen laptop, occasionally modifying them with digital streaks, drawings, collagistic overlays and whatever fantasies seemed apt to the faithful reconstruction of the facts, printing it all out on the small printer, before feeding the sheets of paper into the typewriter carriage so I could add some brief remarks.

I gradually forgot my initial objectives, and began doing whatever came to mind, adding in playful shapes, sublimations of the state in which I found myself, potential lifelines, like I was on holiday, or taking a long weekend; like I had entered a childhood state.

I did a lot of these, certainly 500-plus. Here, as an example, are images corresponding with the days I spent there:

I realized that in this last photo I had been pasted into this inverse world, I had seeped through. And that, quite clearly, my life was being televised. I wondered how many TV-seers might be watching me. Minutes later, I became aware of the ridiculous thoughts I was having, felt worried.

37.

I woke up one morning, morning number 20. The TV, as ever, was on. They were doing a rerun of the second series of Moonlighting, which drew me in for a minute. The camera was on the chair, a glass of water next to it, the illustrated towel hung in the bathroom, and out of the corner of my eye I saw that, over by the door, there was a piece of paper on the floor. I didn’t react at first. I sat doing nothing, suddenly feeling myself to be the target for this sneaking paper creature that had entered my space. It must have been there on the floor for hours. I got up slowly, afraid to even touch it. I looked at it for a long time, down between my bare feet. Finally, crouching down, I picked it up:

Agustín (or whoever the fuck you really are),

I have thrown the contents of the guitar case into the sea.

The guitar case itself I have buried on the path down to the beach.

I am still at work on MY Project.

As far as I am concerned, you, sir, can do as you please.

Agustín Fernández Mallo

I sat down on the bed. I reread the message a few times. Quite a few times. I put the note on the TV ventilation grille. I embarked on an unconscious peripatetic simulation, pacing the room, but soon found myself taking photos again, adding typed remarks beneath, musing, with no particular goal in mind, and with Neapolitan songs drifting up unceasingly from his studio. In some way I believe I just didn’t want to accept that this message meant the end of everything, of our Project – it simply didn’t exist any more – or it did, but at the bottom of the sea, and that, along with it, I no longer existed. Not long after, with me trying to take another photo of the TV, a sudden flash filled the viewfinder. I looked up from the camera. The heat being given off by the TV had set fire to the note: it blazed for a few seconds, leaving a little pile of ash.

That was when I decided I had to go out: I had to check whether the note was true.

I had neither torch nor candles. I waited for a full moon to rise.

38.

I pulled the typewriter keys out of the doorframe and padded barefoot down the stairs. Silence hung over the place as I came past the reception and out into the gardens, through the 3 barbed-wire gates, making my way along the track that led to the beach. I covered the 2km with the lights on the island-turrets as my guide, and, to the right of the final bend in the path before the rice-dunes, saw a rectangular hump in the earth, clearly recently dug.

I began digging manically with my hands and feet – my sore-covered feet from the walk – and, half a metre down, came to the case, opened it, nothing inside.

I could have taken it with me, but for what? Then, an act of genuine exorcism, of pure mourning – at least that was my intention – I put it back in its pit, filled in the pit, picked some nearby wild flowers and used the stem of a shrub to tie them to a stick I found, which I then thrust in as a headstone.

This was perhaps the strangest, most innocent thing I had done in my life.

Then something changed.

39.

He moved into his studio full-time: the music began to play day and night.