5.

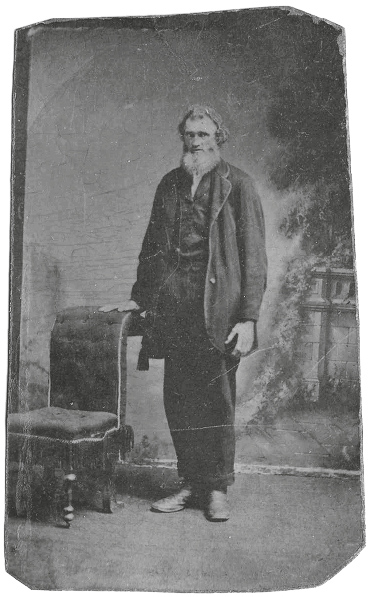

Should this journal be found and I not with it, I enclose here my likeness. This is I, for certain. Or, rather, I when last documented. I wonder how I differ now. I am not especially fond of this tintype but here it is, affixed on the page:

I leave this here for my son. I hope it shall find him: a blessing, a memento of his dear old abandoned father, a little proof. It was supposed to be taken to celebrate his first day of school, but as you will notice, the schoolchild is absent. But I must confess that I had another idea, behind this one: I was hoping the portrait might be used to announce my creation—a little proof of my great work to send into the world before me, to attract the crowds. Collodi was long famous for nothing, but now, I thought, all the world should soon flock here to see my hand-carved son. That anyway was my hope when my thoughts went tintype.

It was taken at the shop of Master Paoli, he of the greatest of stores in all Collodi, where one might purchase anything from cheese to nails to schoolbooks to duck feathers and horsehair. In the back was Master Paoli’s studio, where he took his (locally) famous photographs. And there, that day, was I. But as you see, the seat is empty. I had painted the backdrop, a commission from Master Paoli. It was a piece of artificial countryside and architecture, a trompe l’oeil: an eye lie. Having not yet been fully paid (some part of this payment was taken up in a schoolbook), I came to him sometime after my woodenlife went to school and he agreed to lend me his jacket for the occasion. As you can see, the jacket is made for a stouter man than I. I look worried, as my boy had not come home. I am looking away, anticipating his return.

And I own it: I was expecting not just a boy, but a fortune. I was wishing not just for family but also for fame. Do but consider that. How can one stomach such ingratitude? I blanch to think of it now. What fathering was that? How it shames me today. My past and present are not friends.

Some days I pray for him not to come, not to join me in this death. But come he shall, one day. I fear it so.

My son, I dream of you all nights. I search for you in my dark sleeping. My child, my pine nut, Pinocchio, how the thought of your living warms me now, all my doubts long banished. I smile, sometimes laugh, at the joy of it. Some scoff at pinewood; some will have mahogany, chestnut, rosewood, oak. But for me, please, only pine.

At times, I admit, I have become angry. At times I have lashed out at the wood around me. I have made me a little fire in fury. Once, in my fury, I even broke a bit of Maria off in my hand. Just a little. But now my fury and my Maria piece are gone with the ash.

But . . . to run away like that! To break away so surely.

Oh, my boy, keep running still—and be wary of the water. Oh, have you come to ground yet?

But to throw the child out to sea! My Pino set adrift, exiled from land, forbidden a home. I see him, I do see him lost on the great sheets of water. There’s no one with him there. He is all alone with his terror. Smashed at by the waves. He needs not eat, my boy, but the salt water may do him such harm. Oh my boy, do not rot.

He cannot float forever.

Even wood wears out.

Keep up, my boy, however you can, keep yourself dry. The varnish! Yes the varnish will help you now. Don’t be frightened. You shall find land.

One more word: Avoid any island that moves. For it is the shark, and it looks for you. Swim, swim away from it!

Are you, Pino, yet afloat? How terrible not to know. How monstrous to be so kept in the dark. Pinocchio!

I draw him now, lying out. Washed up. On land again. But I cannot tell by this drawing whether he is alive or dead. Which way does he fall?

There are but four candle crates left. I must be more sparing.

I have by now many pieces of broken chinaware that have come in with the post, little pottery crumbs of my fellow human creatures. I collect them all up, it is a pleasure with me. But today something new that I have never known before. My host has lost a tooth!

I have found its tooth!

What victory this is.

How I do laugh at it, this monster’s fang. What harm has this weapon done? What crushing? And now it is mine.

What must it have swallowed in its time, this creature?

A schooner.

A carpenter. That much is certain. And now its own tooth.

People, I suppose, with fake teeth in their heads, wooden or secondhand, must live in constant fear of swallowing a tooth. How often are milk teeth swallowed? I think it must be very frequent. Once, when I was a child, I swallowed a tin soldier. Down he went into me. Later he emerged again, but even after he was washed off, he seemed most changed by the experience. He looked, I thought, devastated.

What else, I wonder, have people swallowed that they ought never to have had within them? Fish bones? Chicken bones? Flies? Shells? Nails? Buttons? Pearls? Marbles? Dice? Small animals? Lead shot?

Do people with imitation teeth, I wonder, fear they are becoming a sculpture?

I shall scrimshaw this tooth. Scrimshaw: might it be the most beautiful word in the whole language? Though it suggests too much time on one’s hands. It is the occupation of the listless. Art comes from doldrums. Sailors with sharp points carve time on bone.

But what to carve? I thought at first of a whaling scene, depicting the creature being destroyed. I’d draw vengeance on its own bone. But now I think I should rather like to see some flowers here. I shall, with sharp point, drill cut flora upon it. To defeat the object that way, to change its purpose.

The darkness I know is one day closer, again.

I must take some pride—what pride I can—in myself.

And yet: First of all the losses, before I lost my father, long before my son, after Agnese and Sylvestra but before Jacopa and Antonella, I said goodbye to hair.

I am bald, I confess. There is no hair on the top of me. It ran away years ago. There is something very crude—something, why not say it, lewd—in the bald head of a human. The roundedness of it is at once comical and distressing. It is too intimate, it reveals too much, does the naked shiny topmost. As if I had my bare bottom on display. It makes a mockery of the dignity of the human species. It is a kind of autumn, when the head starts to lose its shelter. My autumn came early, in what should have been a longer summertime. Like a dog I found my hairs everywhere; I was shedding youth. I began daily to expose more and more of myself in public. My father before me had suffered from this disease, and no doubt blessed me with the same profound absence. But unlike my father—who allowed his naked pate to be always with him, a cannonball to youth, which by bowing down he pointed at people here and there—I decided as soon as the patch of skin was clearly growing, overtaking the land of my precious locks, that I must seek professional assistance. There was a shop I had in mind, it was Master Paoli’s of course (a new business then, Paoli much younger), and I hurried to it. I entreated:

“Excuse me, please help. The garden atop me has gone barren.”

“Come again?” Paoli’s response.

“I wilt in the north.”

“I’m sorry?”

“I have been abandoned, hairly.”

“Make sense, can’t you?”

“A wig, man, and quickly, too.”

It was a little blond, I see that now. The children laughed at me, I see that now. “Cornhead,” I was called, and no doubt deserved it. “Polendina,” “Old Polly,” “Yellow-Top.” But I loved it, my yellow wigness. We went everywhere together. Before he left, my own son even took the wig for a moment and placed it upon his own head, then danced around the room. It did upset a little. But I kept it up. My wig and I were proud together. Even after the years, when my dear wig began to wilt—it is in the nature of things—and some of the wigmaker’s rubber began to show a little, and so it looked, I suppose, less natural, still the lie was there to behold. Even so, I did not abandon my wig, we belonged together, you see, and had wearied similarly over seasons. As time stomps on we do lose things: hair one day, teeth the next. Eyes wear out, ears cannot hear, legs need rest, joints do creak as if they were turning to wood; and inside, the engine begins to shake. Nothing to be done. Natural enough, they say, but still it hurts.

That wig, so excellent a roof, I have lost. It is somewhere out in the ocean; after so long at home atop me; such loneliness it must feel. I wonder, does it seek companionship with the jellyfish? When I fell into the shark, perhaps understanding the terror, it chose rather not to go. So here I am, exposed of pate.

Something, in short, must be done.

Thus, over several days, I have kept a portion of sea-matter sealed in a tin box, where it has dried out at last and become a little like leather. I am, if nothing else, resourceful. From this I have fashioned me a new hairstyle, the height of fashion for today: a wig of finest seaweed. Here inside, I secure it with a dab of fish glue from my glue pot, and there it stays. Hallo! I feel young again, and ready should any visitor come upon me. Should my unlucky son appear at last, he will not find me underdressed.

I will keep this leviathan civilized. We are human, after all.

Sit up! Four legs to a chair! I shall not see your elbows!

Perhaps I may yet escape and save him. Perhaps there is a way. Dig a tunnel? Find a hole? I shall think further on it.

Today, there being nothing marked in my calendar, I have set about the business of making myself a family. I have always been the sort that makes things, and I think I really must start again now, for if I do nothing but sit and groan in corners, then I shall go quite . . . uncertain. To keep the madness off, then, I shall make.

I was an only child. My mother, Iris, was taken away by the Great Collector when I was but four years into the business of living. What did it? Why, dry cholera. The blue disease, the same that took Antonella, found Mama many years earlier. How blue she turned!

Afterward this left but me and him at home. Father, shut off and locked up in mind and body, few words, often a flared anger. Such a poor, hurt fellow; I understand that now.

But no, no! We’ll start again. I shall magic me a populace.

It may take some time.

I did not eat much today. I had not the stomach.

I have with me here, in great supply, a quantity of hardtack, also called ship’s biscuit. I am most fortunate in this companion and it does sustain me, though it gives me little excitement and has caused the loss of two of my teeth (small yellow peas not fit for the scrimshawing). At last, I find, we have come to an understanding: if I do not bite it, it allows me to keep my dents. Hardtack is best consumed with a great deal of liquid; the ideal method is breaking off a piece and sucking upon it, until slowly, with saliva, the hardtack gives up the ghost and becomes edible. It undergoes a great scientific metamorphosis within the cave of a mouth.

I wonder if the same is true of me.

But hardtack, repast of the patient, monotony of the table, has, I have discovered it, another quality! It can only be described as another miracle.

One day (do not ask which, for Mondays here are identical to Fridays, Christmas like the summer solstice, Michaelmas, Candlemas, and Martinmas all triplets), while I was chewing on some ship’s biscuit, I found it of a sudden difficult to get air in me and I choked. I had indeed such a fit of splurting and coughing, such a battle to find breathing, that I dislodged the offending half-mashed biscuit, catapulted the morsel from my mouth and sent it cannonading upon the captain’s table. Panting but breathing, I staggered out of the chart room into the greater hollow to recover—leaving the expelled titbit, undisturbed, upon the land of desk. Forty-eight hours later, I spied the thing where it lay. In disgust I reached to hurl it from the cabin, when I found myself surprised by the touch of the thing. Hardtack, when uneaten, is sharp but flakes easily. Hardtack when eaten is a mush, a paste. But what I was holding now was something else. It was fully white, and hard as bone.

Ah!, I said to myself—for there is no further company—the latest miracle. I danced a little around the cabin. I kissed the wretched gobspat. This was a discovery of great import.

Why? What then did I have?

I had clay—something to sculpt with, a means of making things! True, I should have been happier with a quantity of wood, but there was only ship’s wood for carving, and to pull the ship apart I must harm my home. But here was clay of a sort, and now my days could be occupied with a special purpose: I could make me a person out of clay. Clay child. A further remembrance of my lost boy. It was without any doubt that my fingers, moving in the air at the thought of clay, instinctively sought the shape of son. There was one slight concern: the more sculpture I made, the less food I had to eat. To eat or make? Full belly or empty head? I would rather starve, I told myself, if it meant I could craft one thing or another. So, then, make: create more and live a little less.

I ground a quantity of hardtack, dumped it into a barrel that proved watertight, and added some of the foul liquid that serves as carpet here. I mixed, swirling with greater happiness than I had felt in ages.

I did my mixing, the mush did its mushing, and I made me a head.

My boy. My boy slowly came out to me: life-size, palpable.

I could touch him.

Here, here you are. Is that you? Somewhere, there? Yes, there he is, smiling at me, grinning, but sad, too, I think—a touch of doubt in the face.

Oh, boy, are you alive out there in the world? How terrible it is, the not knowing. Is he?

Do not come here. Do not tempt the great shark, for it is looking for you.

I think of him now, abroad in the world; is he still sea-tossed, or has he come alone on dry land? The crowds that must rush to him, the wooden life. The attention. All the clapping at his wonder. How he must bow for them. I see him clear. But me, what about me? It was I that made him. Do you ever tell them? Is that immortality, then—how the art is appreciated while the artist is gone? If so, then I say I hate it. To dark hell with it! I spit on it! What good can it do me? None. It gives me no feeling.

I’ll have you home! I command you.

But no, no! I withdraw the command. Do not come here, my own!

I did it. Me alone. Ah.

Ah, yes, that face. I do know it, you see.

Sometimes I had to stop the frantic rush of creating him in hardtack, my hands shaking, my eyes too wet. Sometimes it was a little too much and I must run from it. It was then that I knew I had him. There in the clay. I made him as a flesh child again, for fear he may otherwise look dead. To be clear of the divide twixt death and life.

I gave him glass eyes. I stole them from the stuffed owl. It was a sodden beast anyway and no companion, it was daily hemorrhaging sawdust. And he did seem a little to live, then; there was a glint of life in the eyes. I would rather it was wood, of course—living wood. To think of him alive, to remember that first breath!

But there was to be no repetition, no, that was not its purpose, no little Horatio Hardtack, no Sebastien Shipbiscuit. This clay boy kept so still you’d think him dead. But he smiled at me, yes, even if there was a little mocking in it, yes. The purpose of such food-bust is memory, to keep memory alive.

Look there! There is a naughtiness in his face, is there not? Of course there is, he was no milksop, he was no corner child. There and here he is. You live! I made you! A likeness from my life, pulled out of the past and into solid biscuit.

Solid. Proof. Boy. Pino.

I should, yes, I should rather it were wood.

There is a stick here, too, a very good stick that came in with the post. Sticks are wood, after all, and I am susceptible to wood of any kind. I had put it on a shelf when it arrived, gazing at it as if it were Meissen porcelain, delftware, Whitby jet. The stick and I had known each other perhaps a week when suddenly I found its purpose.

Nose!

Yes, I have given the stick a name. Nose, it is called.

I like my bust well enough, though in honesty, hardtack is not the liveliest of materials. But wood! Yes, nothing better. I took my sculpture in hand and I gave my boy a nose of wood. This much, I said, I can do for thee.

How it sticks out! What a prominence!

A nose to match my boy’s own long snout. A nose to honor, at last.

My hardtack boy looked so much better with the stick there, as if he were coming to life. Something like Daphne turning into tree, rushing into living wood.

I wondered for a moment if I should trim the stick a little, but I have not the heart. The memories. The saw. The switch.

I leave it be.

Finishing the bust of my child is another little bereavement. I pat its cheeks. It is bitter, sweet.

Now that it’s done, I find myself talking to it. Sometimes telling it off. Why did you pull my wig that day? Why did you kick? You are mine. Why, why, did you run away?

How dare you? How are you?

Come home. You’ll not run away again, I’ll see to it.

NO! NO! YOU MUST NOT!