7.

I dwell, some days, on the shape of my wooden child. The roundness of his skull, the curve of his spine. Yes, yes. The grain in his face like freckles on other children. The whole wooden constitution. The complete child. How the joints are. The fold of his knee. Elbows! His dips and bends and the harness of his little shoulders. Wooden clavicles. Wooden toes. The smell of him! Woodskin. Woodbones. Woodheart. Woodlife.

He cannot grow, my boy. (Except, of course, the nose.) Not like all the others. Wherever he is, he stays as he is; he is constant in his carving. (Unless of course the sea diminishes him.) He is not, may I say it, unlike those wooden men found in the holy houses upon their crosses. I have seen many such a wooden youth. In the Church of the Holy Spirit just by the river Arno in the city of Florence—I walked the twelve hours there in search of my son—I sat to rest in the chapel, and there before me, in my despair, was a young man made from a linden tree by Michelangelo Buonarroti Simoni when he too was young. So pure and sleek, oh, the gentleness of wood.

But even Michelangelo’s boy, unlike mine, was made dead. His eyes are closed and he will never wake. But mine. How he kicked! Ha! Ha! He kicked!

Did I dream it? I sometimes wonder. But I cannot say. My head is not quite to be trusted. What is certain is that, last night, I carved again. But am I to be trusted?

I have been drinking. I have been at the wine. I tried it and found it went down very easy, and so one tin mug followed another, until a spirit grew inside me. It seemed to me like the very spirit of carving. There are ship’s tools here, and the Maria is a wooden lady. I thought, I should carve again. But did I? Or was it only dreaming? I think I may have spent hours at the wood. And yet, if so, then where is my labor? Where the proof of my work?

Last night I think I made a child again. Oh, what a sin.

I pulled a portion of the Maria apart. I see where it came from. I woke up in the morning and found it gone, and gone it remains.

But such a face this time—a squished face, an ill-faced child. A wrong-faced boy. Not like the first, but a twisted idea of life. A shadow creature. A spleen child. Something from the deep, a dark, unhappy thing is what I made. It was the wine filling me with bad blood.

And then this thing I made, it scuttered, it spidered, it clicked on the floor.

It stuck its tongue out at me, a tongue black with wine.

A child made of unhappiness, a black bone child.

I carved him in the night, drunk and full of horrormood. I drunk-dreamed him up, this ghost of dark wood, this child of the Maria and me. And he moved!

Not the first son, but like the first son:

He kicked!

Like the first son:

He ran away!

Like the first son:

I have a bruise here where he struck.

But can I be certain? NO! I cannot. After all, parts of the Maria do tumble and disintegrate of their own accord. And I cannot fairly say I remember the carving, the making of the boy.

And the ill-faced puppet is nowhere to be found.

If I made you, I am so sorry. May I unmake you? May you come undone? May you go back to the black wood you were?

I have drawn him out in ink, the nightmare child: This is he, this is his likeness, as close as I am able. What a horror, this wooden wrongness, this totem of despair.

No. Finally I do not believe in you! Olivia, you were here. Tell me, am I imagining it? But Olivia only scuttles on, dear little.

The thing came out of a bottle, an ill-humored genie. I’ll put you back.

I look at the wine bottles. I shall uncork no more monsters.

No. Finally, here is the decision: I did not make that unchild, that nonocchio.

Instead I made only bad dreams.

Never noboy. Do not believe in it.

I could tidy myself up. I could neaten my beard. It has grown, you know, very long. It is an outrageous thing, this blanket attached to my chin. It is, more and more, my clothing. Indeed I shall not trim it, for to tell the truth I am proud of it. All my own work, such growing! Perhaps, if I am ever to step upon anything but shark flesh, should I ever have a different land, I might make a good living exhibiting my great bearding. Perhaps this is the longest beard in history? Perhaps there is my fortune! Imagine a town square, a man sat in the center with his beard coiled round and round, quite filling the place. I have tripped upon it often, and shut it in cupboard doors and snagged it all over the place, but I’ll not part with it. It is after all Olivia’s home. I like to lay it out and step back to better contemplate its lovely length, to see Olivia about her playground. How it makes me smile. It does me good. I have had bad dreams of it being gone. I have a terror of waking up clean-shaven.

And besides, how else can I tell how long I have been here if not by the hairs of my chinochin? It is an excellent timekeeper.

Beard clock.

Hair diary.

I have seen the ill-faced child again. In the dark. He’s here when the candle stutters. When I blow out the candle, he comes in an instant. There in the darkness, the unhappy shadow. A cruel spirit—a wooden curse. I fear he means to hurt my boy.

Quickly, quickly! Hurry now! Something other.

Oh! Tomato! I have just remembered you. Please forgive that it has taken so long. Tomato, lost to us now, I dedicate a little prayer to you. You would like a tomato, Olivia. I would share it.

Dear God, bless all the dear tomatoes. Dear God, in case you have forgotten, I’m down here in the belly. Dear God, I ate ripe tomatoes and they were so full of nature and the world. Dear God, return me, please, to the tomato places.

What can I grow here?

I have no sun. What may I grow?

Hair. I grow hair. Scarves of it.

Sometimes, in the night, I hear the ill-faced child breaking up the ship. Smashing it! Yet when I rush to the noise he is no longer there—and yet, sorrowful, the Maria groans. And comes to pieces.

I am being haunted. It is a spiteful wooden thing that haunts me.

Which shall go first, I wonder, mind or ink or candlelight or eyesight?

What helps me, most of all, is writing in this book. I must find something solid to do, something rigorous and time consuming, something true. Something honest.

There is a mirror here; it gets the news of my decaying. There I am. Still there. What sores and infections.

What, you again? I say when I see me. Hallo! I’ve seen you somewhere before, haven’t we, Olivia?

In this theater there is only one actor (forgive me, Olivia) and the scenery never shifts, only ages.

Well, then, I suppose it is a piece of humanity. Aren’t you? I whisper to my reflection. Do it then: A self-portrait. And let Olivia be the judge of it. To set beside the son.

Great artists, having themselves generally available, do portrait themselves. It is a familiar business. Done again and again, over many years, it is a thorough contemplation of time’s bite.

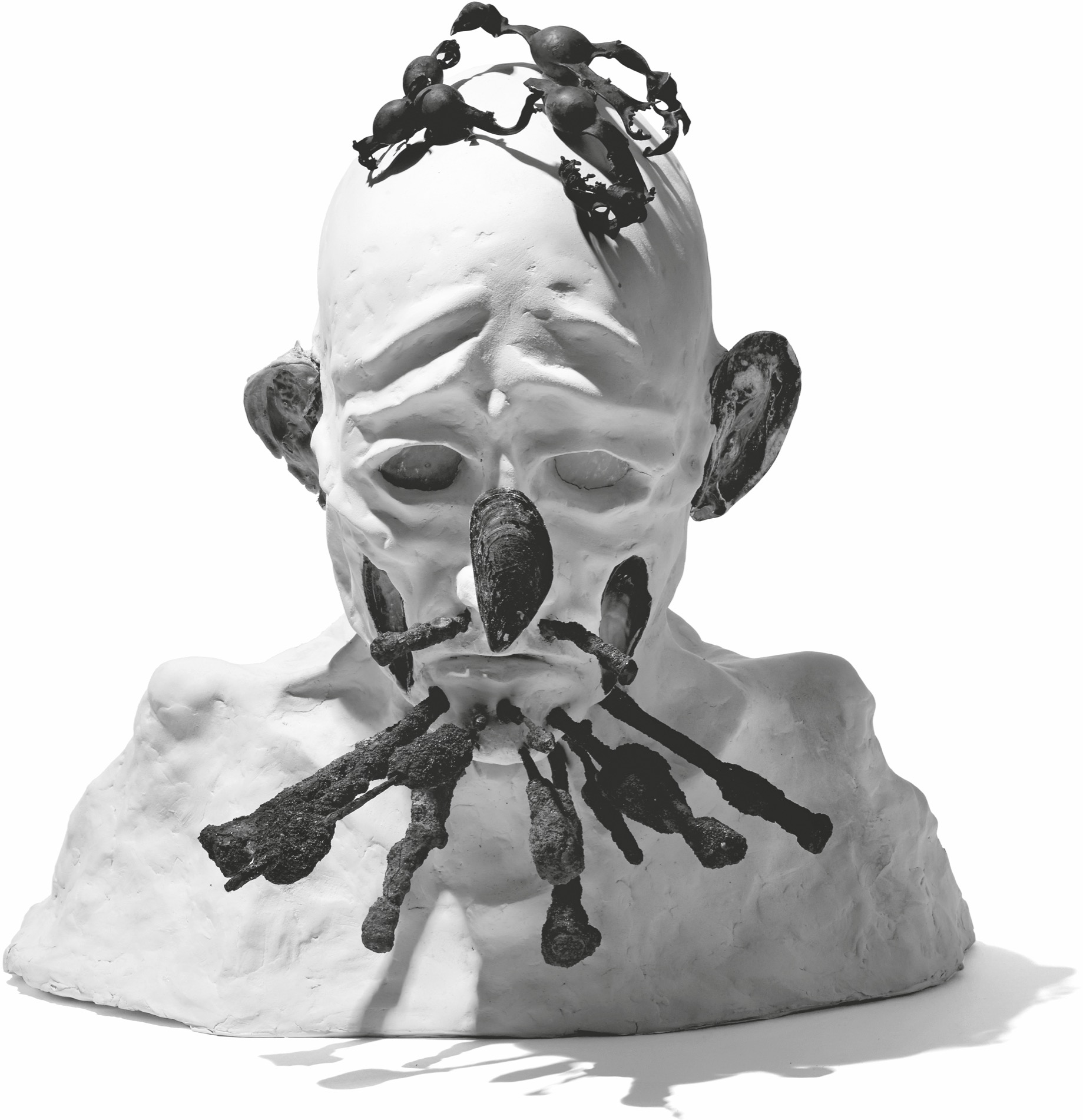

I do it in hardtack, as a companion to the errant son, missing and so missed. I observe me and duplicate myself out of ship’s biscuit. I make myself from my lunch. I build myself up. Come now, be smiling. But the smile keeps falling from the face. The hardtack droops down, it is honest stuff. It is too, too white, this new me. As I busied away, I had the sudden idea that I would decorate myself with some of the furnishings here about and thus add a little color, a little companionship, to my face. No medals, no, but rows of oyster and mussel shells for decoration. Eyes! My son has his glaring owl eyes, I should give myself eyes. My eyes, each time I look, are blue. And I have found, among my treasures, two blue pieces of sea glass, of such beautiful blueness, rounded and kissed and tumbled by the sea, tossed and played with until all the edges are curved out and can no more be danger. Sea: sandpaper. These I have made mine eyes. Oysters for ears are perfect. And a mussel for a nose, it has the bend of my snouting. And mussel shells, turned inside, to represent the hollows of my cheeks.

I have grown thinner since I came here, as who would not? Atop my head no crown of gold or thorns, but rather a coronet of seaweed. And for my beard a fine collection of rusted nails. (Some of these I have, with alarming ease, pulled from the Maria. With what troubling swiftness they have come out. My home! My home is rotten.) All these gifts given me by my gaoler. Yes, I have been most busy this morning!

That is I. Yes, yes, very like! Self-portrait bust with two oyster shells, three mussel shells, kelp, tinted glass, decayed nails. I stand back to admire it—and I start to shake. What do you think, Olivia? She scuttles away, hides deep within my beard.

It is not a pretty thing, that head there.

No, it is not. It is something beastly. Suddenly, I am terrified by it.

I find myself shrieking at it, howling.

A sea troll!

Monster of the deep. Am I, then, the monster? Do I nightmare myself?

I am recalled now of a certain artist. (Jacopa, it was, who told me of him.) A painter of little repute, from the land of Norway, a haunted place where ghosts are met on every street corner, in every wood. The painter lived out by some fjord on the edge of a deep forest, and there he painted, as his subject, great hulking trolls. Big grim faces, creatures as big as mountains. Many-headed, they were, clumsy and crude, eating children. Painters of drawing rooms and society asked why he painted such silliness, such fantastical subjects. He answered, at last: because they terrified him. He told them, I cannot paint a landscape without putting a troll in it. What you would call reality, what you see as truth and the everyday, doesn’t interest me. Not for me the small fragilities of daily life, only the certain monster of death. Theodor Severin Kittelsen was his name. What a way to live, to paint trolls only. To fix on nightmares. Here, in the fish, I understand him better.

In truth, I am glad I have remembered him at all. Things I once knew, you see, come back to me only fitfully, at random. How to make mutton pie, for example; how many minutes for the perfect egg; my nine times table; which snakes have poison and which do not. Latin conjugations, verses from hymns, the Magnificat. And the man who painted trolls.

And here am I, and there am I, sea troll.

Boo.