Oh! Go, go away. You frighten me!

I am coming.

Help!

Knock!

Knock!

Bang!

The roots have come now into the chart room, spreading from ill-face, covering the walls. But I have yet possession of the cabin, and I pull myself inside. There, within, I am still a man in a room, safe a little while yet.

The bed, you see. Captain’s bed. And my light. I may set light to the ill-face and all its spreading limbs. I’ll make such a fire, I’ll burn ill-face to death: that shall be my ending.

And yet—I know this now, I cannot avoid it—it is all my doing. To create such a blackness, it did come from me. I gave it breath. And now I create the fire that will quench it. The fire will destroy the shark, and it will set my own son free.

Ill-face is nothing like my little boy. Oh, to see him again—how his face would put the blackness out. If I could but make him once more. A boy; a great, proud boy.

I love, I would tell it.

And let it free, let it swim, let it go on.

Yet here is wood before you, old man: wood still fresh, the solid bed, the boards. The tools. Might you, with one last breath, use it?

I am sorry, my son. I am so sorry. No hooks, never no more.

I, frightened, frightened you away. Did I not?

Can I bring you back?

When ill-face taps at the door, tap tap, I reply with my toc toc at this new wood. It leads me, the wood does. It always has if I let it.

Come, I tell it, break free my sorrow. Come, I beg thee.

Still, though, Joseph: let the wood do it. Toc. Toc. Tap tap. No, no, you may not come in, you may not.

It comes now, the wood—how it comes along. I feel its sides. Not quite a boy, yet, but I shall let the wood be free. No. No! This is not right, not yet. This is no child.

Trust the wood.

Can I? Did it? Move a little. Was there? Life?

Come now. Yes! It wriggles in my arm! It thrashes!

There, Pino. Come, my woodling, breathe, beat.

It moves! It does! Look!

Tap!

Toc.

Tap! Tap!

Toc. Toc.

But no, wood, you are wrong! Wood, you mustn’t. This is not feet but a tail.

A wooden tail has just slapped me in the face.

It is hard to hold back, what flippers, Pino, surely. Are you fish now?

And yet nose again—great nose, for how else can I know it is you? Come nose, nose nose. Oh, how the nose stretches out, in a spiral, to a point.

This is no wooden child I make. Look there—it has a wooden sword! Look at the weapon! Such fight in you!

Tap! Tap!

Come, hurry, there’s no time. The Maria is splitting. Come, woodlife, I’ll sharpen your sword. How it grows out of you, of your face.

Eyes, little dark eyes. See me! It lives! Oh, it LIVES!

Crash!

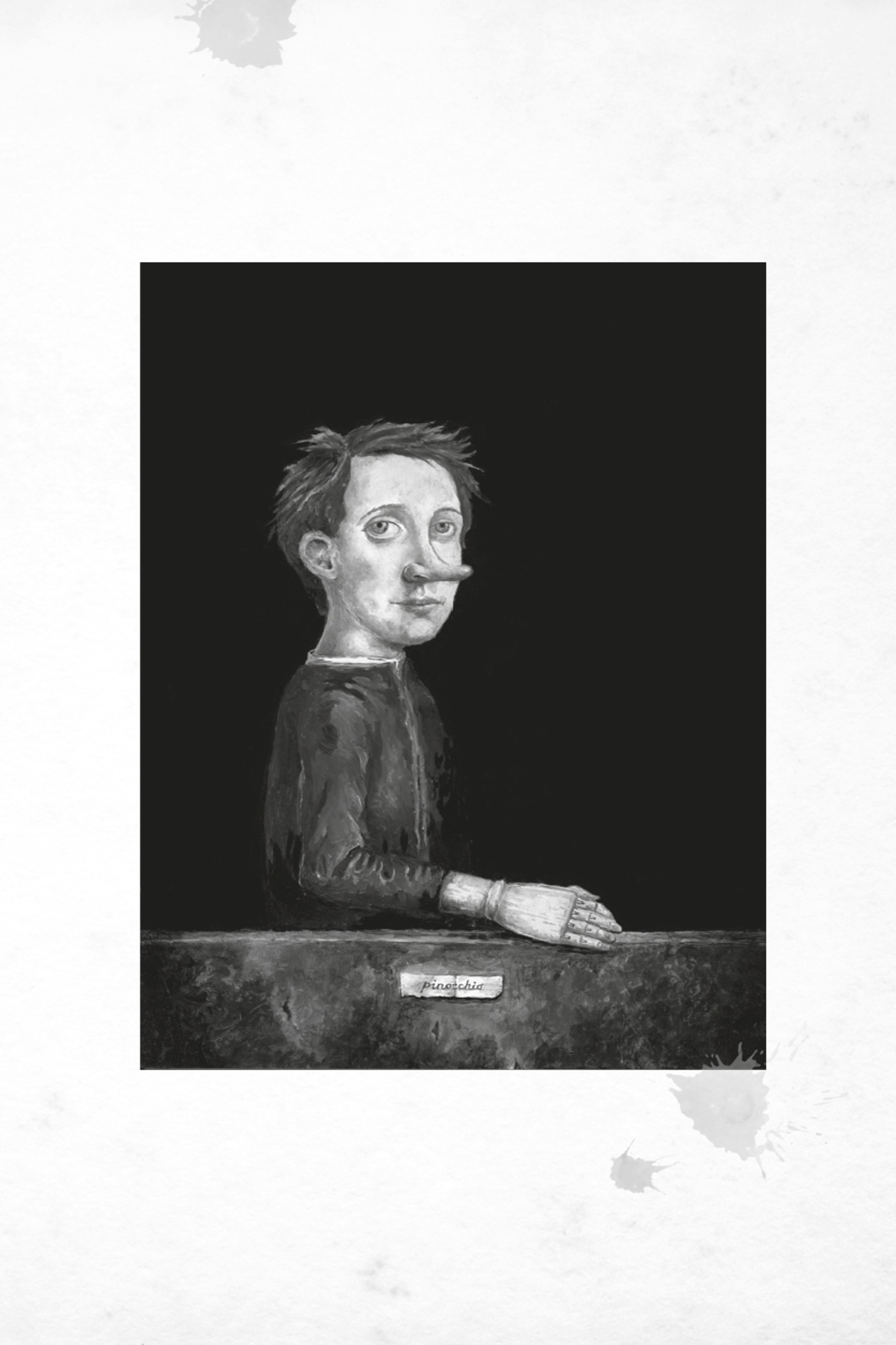

It is a fish! A wooden fish, but how it flaps in the captain’s cabin. Water, water, it must breathe. Oh, my fishson, fishboy, fishchild. Look at you: Nose of the Sea! Narvalo! Pinocchio’s good spirit! That is who you are. Who else could you be? A sea unicorn! A narwhal! The fish with the sharp snout! Impossible beast!

Come now, my love. Let us get you out, for the ship shall not last long. I made! Again!

Crack! Boom!

What a smashing! Yet at last I know my purpose. I take hold of my wooden son, my boy come a narwhal, my own art, and I break open the door with my own strength. I hold the wooden fish close to me.

It is there! Ill-face! Just there, beyond the door, thick with his roots. How wide it opens its mouth at the gleaming wood I hold. I hold up the wooden fish, and ill-face sees it. It opens its black mouth so wide! Such a scream it makes.

And I scream back.

And my fishboy screams. A child’s voice! Yes! Yes!

And along we rush, down the corridor, while the ill-face is caught in his scream-shock.

There’s a great rent in the ship now, I can feel it—a terrible new collapse. She has broken in two, opened a great hole, and we come to break too fast, too fast. We slip from the edge, we fall, we tumble down in the muck, until we are all down there, upon the sharkfloor.

But wait—

I dropped him! The fish, the sharp-nosed fish!

Where, boy?

And now the ill-face is coming spidering down. Black roots creeping all about, amid shrieks of splitting wood.

Ah, but there he is! The little wooden pinwhal, flapping hopeless in the damp. Quick, ’Petto, leap that carcass, rush your old bones. The dark branches are coming on!

Pick him up, wipe him down. Then run.

To the shark throat. The throat. Hurry, hurry now!

How he writhes. Soon boy, soon!