Afterword

By Athelwold Ezekiel Greem, M.D., Vinalhaven, Maine, U. S. A.

To the reader:

The story of the monster is well-known to the people of my island. On January 23, 1887, a sea creature the like of which was new to us, and very strange, was beached upon our land. There was no hope of saving its life, for when it landed on our shore it was already some time dead; there was plentiful evidence of rotting about its wrinkled skin. I am sorry for that, for in many ways the advanced putrefaction had robbed the monster of so much majesty: it seemed, to my mind, enfeebled as it lay helpless and expired on our common land. We did, however, make a holiday of it. The whole town came out to visit. All shops were closed. There was something extraordinary to be seen, and child and ancient alike came to be near it.

I am no exaggerator; I am a doctor. I apply myself to facts as much as any person may. But there, upon the sand, was a new fact. A fact not entered in any of the five hundred volumes of my personal library—good library though it is, and one with no small fame in this locality. People come from all corners of the island to visit my library. True, it is not a very large island. But it is very full of facts. And there, of a sudden, was a very new fact before us.

A very large fact.

Nothing this size had been previously known. Dolphins had washed up, sharks, too, even sperm whales. But this was something new. How can I say it so that you who did not see it may comprehend its enormity? It changed the very landscape, as if there were now a hill, a big hill or small mountain, where before there was none. It quite filled the beach with its corpse. A whole locomotive could have driven through the tunnel of its mouth with great ease, allowing not just the engine but four or five carriages to follow and still be contained. It changed our very conception of size. We had not known anything was capable of such amplitude. It was as if God had given us a hint of Himself. Or was this fresh evidence of Hell? We felt a chosen people. Or a cursed.

Was it real, or were we dreamers, we asked ourselves. Once we had put our hands to the creature’s appalling skin, however, we could but answer that this was an absolute truth. Was this the same gross form—I have done my investigations—spotted passing through the Strait of Gibraltar in 1875? Or the immense shape recorded by the crew of the RMS Zanoni in the Gulf Saint Vincent? Or even the dark shadow that followed the Russian monitor Smerch for two whole days in the Arctic Circle? I suspect it may indeed have begat that outlandish rumor. But monsters—monsters are fact, this I know.

What were we then to do with such an unlikely spectacle?

It could not be eaten. Not without fear of illness. I estimate it must have died some weeks or even months before its arrival, and indeed there were visible bites from other sea life about it. However, while it had been sampled by other creatures, it seemed somehow to have repelled them. Thus it was left alone to roll in the ocean until at last it settled here with us. Was it a gift? Was it a punishment? Should we have boasted of it to the world or should we have covered it up?

Before we could answer these questions, it became obvious that something had to be done about our new habitant. Good or ill, it could not be left where it was. This colossus, though dead, was a danger to us.

It poisoned the air. It had been with us but two days before this hazard began to show itself. Babies started to sleep longer and were harder to waken. Milk began to spoil within an hour of arriving at market. An old woman died while sitting on a bench in Skoog Park. Then, on the third day, we woke to discover that small spots had begun to form on the backs of our necks. Our jaws felt stiff and we complained of headaches. Our hair, in certain cases, began to fall out. Teeth did likewise, and there was a certain yellowing of our skin. Birds dropped from the sky, quite dead. Our dogs vomited in the streets, and cats hissed and fled us, fur on end.

I insisted that the island be quarantined. If all life on Vinalhaven should come to an end, far better that only our island be afflicted while all humanity beyond remain safe. Ferry service across Penobscot Bay from Rockland was abolished, as were journeys by all other craft. We excluded ourselves, for a time, from the rest of humanity.

The great fish was the cause, and that fish, once our pride, now became our terror. We had to get rid of the thing, to destroy and dismantle it, though even the stoutest among us found their strength ebbing each day. If we did not go to it soon, there would be little hope for us.

But stay a moment.

I am, as I have said, a medical man of curious mind. I knew that a simple walk around the beast would give me much information, but I required to know what was inside the deceased. This foul creature, this horror-mound, had to be opened up and fractioned, for only after we had burned it or buried it could we hope to breathe freely again. Volunteers were called for, and twenty of our strongest came forward, dressed in fishing leathers, while the remainder were told to keep indoors until the all-clear had been given.

Down we went unto the beach, with long knives and treesaws to make that one big thing into many a smaller thing. In the name of science I wished to have some knowledge of its inner workings, and so I commanded that the belly be split open and the contents drawn out. What sawing and wrenching there followed, and then what new abominable stench, but the thing was opened now and a tunnel made within the flesh. I asked who would go inside and enter the inner world of the creature, and receiving no answer—for all were in dread fear of it—I had a closed lanthorn lit and climbed in by myself.

It was a slippery road, bordered by thick walls, and I soon began to wonder about the wisdom of my adventure, about whether this doleful palace might collapse about me. Still, I went on until I reached a vast opening, like some hall or a church, and found myself within the main cavern of the creature. What a strange emptiness it was! My flame did not immediately make sense of the surroundings, but ere long it seemed to me that yonder was a familiar shape. How could it be? But true enough, there it was: A ship. Broken and rotted, and much of it burnt, yet surely once a ship, long since swallowed by the colossus. Were there, I wondered, any survivors inside? I called out, but there was no reply. Indeed, it seemed madness to hope for life within such a tomb. I went closer to the unhappy wreck then, and using a rope slung over the side, I gained access to the vessel itself. The walls were no longer of discernible wood but covered in some filth, secretions of the stomach no doubt. And so I climbed within the rotting vessel—and there I found the objects, the workings, the very museum of a single poor human soul who had evidently been trapped within, eaten and yet living, and had persisted, apparently, for some years.

How I wept then, I, a man of science—at these poor artifacts, at the fate of a fellow creature.

I looked everywhere for some piece of the unfortunate. I called, I searched in the befouled cabins, but no human remainder, no slumped bag of human skin did I uncover. What bones I found—and there were many—were of fish swallowed and rotted in that gaseous hall. There was, too, a small childlike shape contrived out of pieces of broken pottery and glued together, not unartful perhaps, and no doubt precious to its maker. And heads there were, lifesize heads, made from some pale substance; and paintings on wood of recognizably human faces, some large, some quite small; and paintings on shells, too, and bone!

Thus did I make this discovery, one that brought to my mind the cave paintings of ancient man communicating with us over unthinkable distance. Here, too, was life.

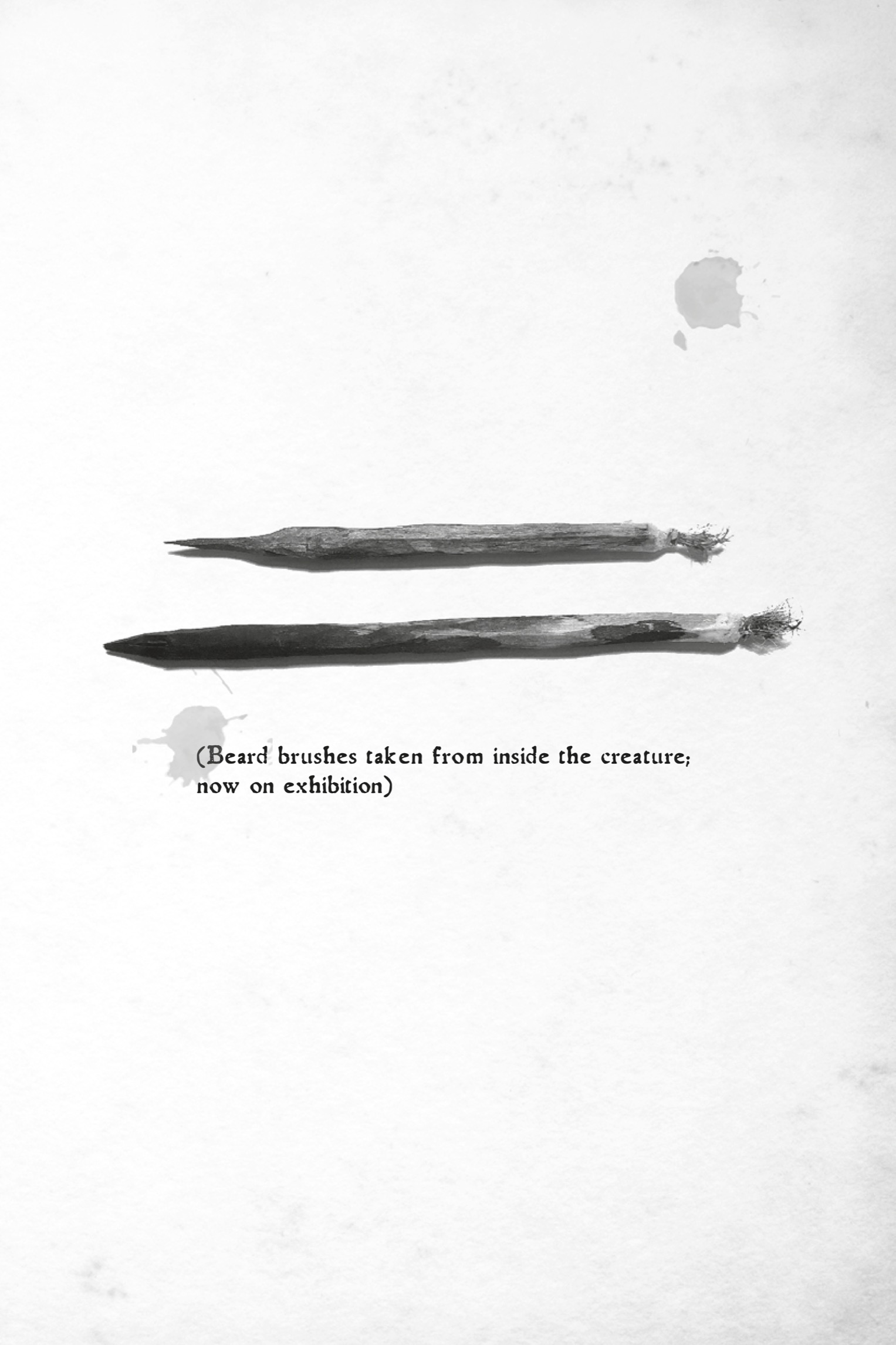

On that dank morning, I resolved that every piece, small or large, of this unfortunate human’s work must be rescued. It must be carefully removed from its place and taken to a cleaner environment where it could be preserved for permanent study. Everything must be saved: The brushes made of his beard. The bone tools. The sail-canvas tablecloth. Paintings on bone, on board, on vellum. And the words in the book he left behind—the diary and the stories—I have had translated into several of the languages of the world. He wrote his stories, it seems to me, to entertain himself, to keep himself alive. I do not always understand him. His delusions of a wooden child, for instance, defy explanation. He seems also to have been frightened of his own squid-black marks upon the page, as if at times a madness gripped the pen. I have had his several objects captured by a camera device, and have positioned these pieces of evidence in the relevant places throughout this book.

The creature, alas, we burned. Such thick smoke it made. I smell it to this day.

The prisoner’s work has taken up permanent residence in my own home. I have lived unencumbered since the loss of my wife and three children to smallpox, and so I have the good fortune of making this collection of a man’s life the newest part of my library. I open my door so that others may come to contemplate.

I have, in the years since, tried to determine the ending of the gentleman who lived inside the fish. I did discover that the entire crew of the Danish schooner Maria went down with all hands somewhere near the island of Ærø in the winter of 1876, but it is clear from the surviving diary that this monster’s last tenant was not among their number. I have sent out pleas in the form of advertisements in papers; I have applied to many universities and governments, no doubt causing much mirth and incredulity. You cannot live in a stomach, I have been told in so many ways. I know that—and yet. No such man living in Collodi, province of Lucca, but there was an abandoned ceramics factory there, and in a ledger was one Giuseppe Lorenzini, long since absconded, who owed many months’ rent on a small municipal room. I have found no further trace of him.

Some nights I dream of that poor old man, and in my dream I am always asking him where he has gone. He has never answered me yet, but I shall keep trying.

My home has come to be known for the collection it houses and has earned a nickname. They call it “Fish House” because it has grown a smell now, like a gas, coming from these certain treasures that have made a home for themselves all over the property. As if the various objects were alive. I like the sound of this name. I have commissioned a sign for the front door:

THE FISH HOUSE

There, then, we are a regular museum. We are open Monday to Saturday, 10:00 a.m. until 4:00 p.m. Sundays closed for prayer.