1

BREAKTHROUGHS TO NEW DIMENSIONS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

There is one spectacle grander than the sea, that is the sky; there is one spectacle grander than the sky, that is the interior of the soul.

—Victor Hugo, “Fantine,” Le Misèrables

Within the past three decades, modern science has presented us with new challenges and new discoveries that suggest human capabilities quite beyond anything we previously even imagined. In response to these challenges and discoveries, the collective efforts of researchers from every profession and discipline are providing us with a completely new picture of human existence, and most particularly of the nature of human consciousness.

Just as the world of Copernicus’s time was turned upside down by his discovery that our Earth was not the center of the universe, so our newest revelations, from researchers all over the world, are forcing us to take a closer look at who we are physically, mentally, and spiritually. We are seeing the emergence of a new image of the psyche, and with it an extraordinary worldview that combines breakthroughs at the cutting edge of science with the wisdom of the most ancient societies. As a result of the advances that are coming forth we are having to reassess literally all our viewpoints, just as with the response to Copernicus’s discoveries nearly five hundred years ago.

The Universe as a Machine: Newton and Western Science

At the core of this dramatic shift in thought that has occurred in the course of the twentieth century is a complete overhaul of our understanding of the physical world. Prior to Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum physics we held a firm conviction that the universe was composed of solid matter. We believed that the basic building blocks of this material universe were atoms, which we perceived as compact and indestructible. The atoms existed in three-dimensional space and their movements followed certain fixed laws. Accordingly, matter evolved in an orderly way, moving from the past, through the present, into the future. Within this secure, deterministic viewpoint we saw the universe as a gigantic machine, and we were confident the day would come when we would discover all the rules governing this machine, so that we could accurately reconstruct everything that had happened in the past and predict everything that would happen in the future. Once we had discovered the rules, we would have mastery over all we beheld. Some even dreamed that we would one day be able to produce life by mixing appropriate chemicals in a test tube.

Within this image of the universe developed by Newtonian science, life, consciousness, human beings, and creative intelligence were seen as accidental by-products that evolved from a dazzling array of matter. As complex and fascinating as we might be, we humans were nevertheless seen as being essentially material objects—little more than highly developed animals or biological thinking machines. Our boundaries were defined by the surface of our skin, and consciousness was seen as nothing more than the product of that thinking organ known as the brain. Everything we thought and felt and knew was based on information that we collected with the aid of our sensory organs. Following the logic of this materialistic model, human consciousness, intelligence, ethics, art, religion, and science itself were seen as by-products of material processes that occur within the brain.

The belief that consciousness and all that it has produced had its origins in the brain was not, of course, entirely arbitrary. Countless clinical and experimental observations indicate close connections between consciousness and certain neurophysiological and pathological conditions such as infections, traumas, intoxications, tumors, or strokes. Clearly, these are typically associated with dramatic changes in consciousness. In the case of localized tumors of the brain, the impairment of function—loss of speech, loss of motor control, and so on—can be used to help us diagnose exactly where the brain damage has occurred.

These observations prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that our mental functions are linked to biological processes in our brains. However, this does not necessarily mean that consciousness originates in or is produced by our brains. This conclusion made by Western science is a metaphysical assumption rather than a scientific fact, and it is certainly possible to come up with other interpretations of the same data. To draw an analogy: A good television repair person can look at the particular distortion of the picture or sound of a television set and tell us exactly what is wrong with it and which parts must be replaced to make the set work properly again. No one would see this as proof that the set itself was responsible for the programs we see when we turn it on. Yet, this is precisely the kind of argument mechanistic science offers for “proof” that consciousness is produced by the brain.

Traditional science holds the belief that organic matter and life grew from the chemical ooze of the primeval ocean solely through the random interactions of atoms and molecules. Similarly, it is argued that matter was organized into living cells, and cells into complex multicellular organisms with central nervous systems, solely by accident and “natural selection.” And somehow, along with these explanations, the assumption that consciousness is a by-product of material processes occurring in the brain has become one of the most important metaphysical tenets of the Western worldview.

As modern science discovers the profound interactions between creative intelligence and all levels of reality, this simplistic image of the universe becomes increasingly untenable. The probability that human consciousness and our infinitely complex universe could have come into existence through the random interactions of inert matter has aptly been compared to that of a tornado blowing through a junkyard and accidentally assembling a 747 jumbo jet.

Up to now, Newtonian science has been responsible for creating a very limited view of human beings and their potentials. For over two hundred years the Newtonian perspective has dictated the criteria for what is an acceptable or unacceptable experience of reality. Accordingly, a “normally functioning” person is one who is capable of accurately mirroring back the objective external world that Newtonian science describes. Within that perspective, our mental functions are limited to taking in information from our sensory organs, storing it in our “mental computer banks,” and then perhaps recombining sensory data to create something new. Any significant departure from this perception of “objective reality”—actually consensus reality or what the general population believes to be true—would have to be dismissed as the product of an overactive imagination or a mental disorder.

Modern consciousness research indicates an urgent need to drastically revise and expand this limited view of the nature and dimensions of the human psyche. The main objective of this book is to explore these new observations and the radically different view of our lives that they imply. It is important to point out that even though these new findings are incompatible with traditional Newtonian science, they are fully congruent with revolutionary developments in modern physics and other scientific disciplines. All of these new insights are profoundly transforming the Newtonian worldview that we once took so much for granted. There is emerging an exciting new vision of the cosmos and human nature that has far-reaching implications for our lives on an individual as well as collective scale.

Consciousness and Cosmos: Science Discovers Mind in Nature

As modern physicists refined their explorations of the very small and the very large—the subatomic realms of the microworld and the astrophysical realms of the macroworld—they soon realized that some of the basic Newtonian principles had serious limits and flaws. In the mid-twentieth century, the atoms that Newtonian physics once defined as the indestructible, most elementary building blocks of the material world were found to be made of even smaller and more elementary parts—protons, neutrons, and electrons. Later research detected literally hundreds of subatomic particles.

The newly discovered subatomic particles exhibited strange behavior that challenged Newtonian principles. In some experiments they behaved as if they were material entities; in other experiments they appeared to have wavelike properties. This became known as the “wave-particle paradox.” On a subatomic level, our old definitions of matter were replaced by statistical probabilities that described its “tendency to exist,” and ultimately the old definitions of matter disappeared into what the physicists call “dynamic vacuum.” The exploration of the microworld soon revealed that the universe of everyday life, which appears to us to be composed of solid, discrete objects, is actually a complex web of unified events and relationships. Within this new context, consciousness does not just passively reflect the objective material world; it plays an active role in creating reality itself.

The scientists’ explorations of the astrophysical realm is responsible for equally startling revelations. In Einstein’s theory of relativity, for example, space is not three-dimensional, time is not linear, and space and time are not separate entities. Rather, they are integrated into a four-dimensional continuum known as “space-time.” Within this perspective of the universe, what we once perceived as the boundaries between objects and the distinctions between matter and empty space are now replaced by something new. Instead of there being discrete objects and empty spaces between them the entire universe is seen as one continuous field of varying density. In modern physics matter becomes interchangeable with energy. Within this new worldview, consciousness is seen as an integral part of the universal fabric, certainly not limited to the activities contained inside our skulls. As British astronomer James Jeans said some sixty years ago, the universe of the modern physicist looks far more like a great thought than like a giant super-machine.

So we now have a universe that is an infinitely complex system of vibratory phenomena rather than an agglomerate of Newtonian objects. These vibratory systems have properties and possibilities undreamed of in Newtonian science. One of the most interesting of these is described in terms of holography.

Holography and the Implicate Order

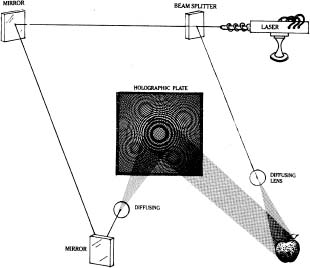

Holography is a photographic process that uses laser-coherent light of the same wave-length to produce three-dimensional images in space. A hologram—which might be compared to a photographic slide from which we project a picture—is a record of an interference pattern of two halves of a laser beam. After a beam of light is split by a partially silvered mirror, half of it (called the reference beam) is directed to the emulsion of the hologram; the other half (called the working beam) is reflected to the film from the object being photographed. Information from these two beams, required for reproducing a three-dimensional image, is “enfolded” in the hologram in such a way that it is distributed throughout. As a result, when the hologram is illuminated by the laser, the complete three-dimensional image can be “unfolded” from any fraction of the hologram. We can cut the hologram into many pieces and each part will still be capable of reproducing an image of the whole.

Figure 1. A hologram is produced when a single laser light is split into two separate beams. The first beam is bounced off the object to be photographed, in this case an apple. Then the second beam is allowed to collide with the reflected light of the first, and the resulting interference pattern is recorded on film.

The discovery of the holographic principles has become an important part of the scientific worldview. For example, David Bohm, a prominent theoretical physicist and former coworker of Einstein’s, was inspired by holography to create a model of the universe that could incorporate the many paradoxes of quantum physics. He suggests that the world we perceive through our senses and nervous systems, with or without the help of scientific instruments, represents only a tiny fragment of reality. He calls what we perceive the “unfolded” or “explicate order.” These perceptions have emerged as special forms from a much larger matrix. He calls the latter the “enfolded” or “implicate order.” In other words, that which we perceive as reality is like a projected holographic image. The larger matrix from which that image is projected can be compared to the hologram. However, Bohm’s picture of the implicate order (analogous to the hologram) describes a level of reality that is not accessible to our senses or direct scientific scrutiny.

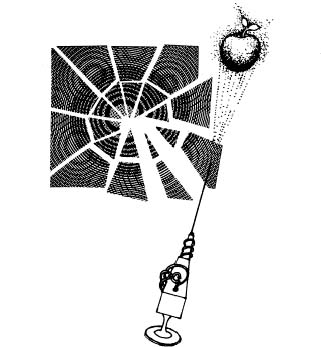

Figure 2. Unlike normal photographs, every portion of a piece of holographic film contains all the information of the whole. Thus if a holographic plate is broken into fragments, each piece can still be used to reconstruct the entire image.

In his book Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Bohm devotes two chapters to the relationship between consciousness and matter as seen through the eyes of the modern physicist. He describes reality as an unbroken, coherent whole that is involved in an unending process of change—called holomovement. Within this perspective all stable structures in the universe are nothing but abstractions. We might invest all kinds of effort in describing objects, entities, or events but we must ultimately concede that they are all derived from an indefinable and unknowable whole. In this world where everything is in flux, always moving, the use of nouns to describe what is happening can only mislead us.

For Bohm, holographic theory illustrates his idea that energy, light, and matter are composed of interference patterns that carry information about all of the other waves of light, energy, and matter that they have directly or indirectly contacted. Thus, each part of energy and matter represents a microcosm that enfolds the whole. Life can no longer be understood in terms of inanimate matter. Matter and life are both abstractions that have been extracted from the holomovement, that is, the undivided whole, but neither can be separated from that whole. Similarly, matter and consciousness are both aspects of the same undivided whole.

Bohm reminds us that even the process of abstraction, by which we create our illusions of separation from the whole, are themselves expressions of the holomovement. We ultimately come to the realization that all perceptions and knowledge—including scientific work—are not objective reconstructions of reality; instead, they are creative activities comparable to artistic expressions. We cannot measure true reality; in fact, the very essence of reality is its immeasurability.1

The holographic model offers revolutionary possibilities for a new understanding of the relationships between the parts and the whole. No longer confined to the limited logic of traditional thought, the part ceases to be just a fragment of the whole but, under certain circumstances, reflects and contains the whole. As individual human beings we are not isolated and insignificant Newtonian entities; rather, as integral fields of the holomovement each of us is also a microcosm that reflects and contains the macrocosm. If this is true, then we each hold the potential for having direct and immediate experiential access to virtually every aspect of the universe, extending our capacities well beyond the reach of our senses.

There are indeed many interesting parallels between David Bohm’s work in physics and Karl Pribram’s work in neurophysiology. After decades of intensive research and experimentation, this world-renown neuroscientist has concluded that only the presence of holographic principles at work in the brain can explain the otherwise puzzling and paradoxical observations relating to brain function. Pribram’s revolutionary model of the brain and Bohm’s theory of holomovement have far-reaching implications for our understanding of human consciousness that we have only begun to translate to the personal level.

In Search of the Hidden Order

Nature is full of genius,

full of the divinity,

so that not a snowflake escapes

its fashioning hand.

—Henry David Thoreau

Revelations concerning the limits of Newtonian science and the urgent need for a more expansive worldview have emerged from virtually every discipline. For example, Gregory Bateson, one of the most original theoreticians of our time, challenged traditional thinking by demonstrating that all boundaries in the world are illusory and that mental functioning that we usually attribute exclusively to humans occurs throughout nature, including animals, plants, and even inorganic systems. In his highly creative synthesis of cybernetics, information and systems theory, anthropology, psychology, and other fields, he showed that the mind and nature form an indivisible unity.

British biologist Rupert Sheldrake has offered an incisive critique of traditional science, approaching the problem from still another angle. He pointed out that in its single-minded pursuit of “energetic causation,” Western science neglected the problem of form in nature. He pointed out that our study of substance alone cannot explain why there is order, pattern, and meaning in nature any more than the examination of the building materials in a cathedral, castle, or tenement house can explain the particular forms those architectural structures have taken. No matter how sophisticated our study of the materials, we will not be able to explain the creative forces that guided the designs of these structures. Sheldrake suggests that forms in nature are governed by what he calls “morphogenic fields,” which cannot be detected or measured by contemporary science. This would mean that all scientific efforts of the past have totally neglected a dimension that is absolutely critical for understanding the nature of reality.2

The common denominator of all these and other recent theories that offer alternatives to Newtonian thinking is that they see consciousness and creative intelligence not as derivatives of matter—more specifically of the neurophysiological activities in the brain—but as important primary attributes of all existence. The study of consciousness, once seen as the poor cousin of the physical sciences, is rapidly becoming the center of attention in science.

The Revolution in Consciousness and the New Scientific Worldview

Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different…. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.

—William James

Modern depth-psychology and consciousness research owe a great debt to the Swiss psychiatrist C. G. Jung. In a lifetime of systematic clinical work, Jung demonstrated that the Freudian model of the human psyche was too narrow and limited. He amassed convincing evidence showing that we must look much farther than personal biography and the individual unconscious if we are to even begin to grasp the true nature of the psyche.

Among Jung’s best known contributions is the concept of the “collective unconscious,” an immense pool of information about human history and culture that is available to all of us in the depth of our psyches. Jung also identified the basic dynamic patterns or primordial organizing principles operating in the collective unconscious, as well as in the universe at large. He called them “archetypes” and described their effects on us as individuals and on human society as a whole.

Of special interest are Jung’s studies of synchronicity that we will later explore in more detail. He discovered that individualized psychological events, such as dreams and visions, often form patterns of meaningful coincidence with various aspects of consensus reality that can not be explained in terms of cause and effect. This suggested that the world of the psyche and the material world are not two separate entities, but that they are intimately interwoven. Jung’s ideas thus challenge not only psychology but the Newtonian worldview of reality and the Western philosophy of science. They show that consciousness and matter are in constant interplay, informing and shaping each other in a way that the poet William Butler Yeats must have had in mind when he spoke of those events where “you cannot tell the dancer from the dance.”

At about the same time that we were beginning to have major breakthroughs in physics, the discovery of LSD and subsequent psychedelic research opened up new revolutionary avenues in the study of human consciousness. The 1950s and 1960s saw a major explosion of interest in Eastern spiritual philosophies and practices, shamanism, mysticism, experiential psychotherapies, and other deep explorations of the human psyche. The study of death and dying brought some extraordinary data about the relationships between consciousness and the brain. In addition, there was a resurgence of interest in parapsychology, particularly around the research of extrasensory perception (ESP). New information about the human psyche was also being generated by laboratories experimenting with modern mind-altering techniques, such as sensory deprivation and biofeedback.

The common denominator of all this research was its focus on non-ordinary states of consciousness, an area that in the past had been grossly neglected not just by traditional science, but by the entire Western culture. In our emphasis on rationality and logic, we have put great value on the everyday sober state of mind and relegated all other states of consciousness into the realm of useless pathology.

In this respect, we have a very unique position in human history. All the ancient and pre-industrial cultures have held non-ordinary states of consciousness in high esteem. They valued them as powerful means for connecting with sacred realities, nature, and each other, and they used these states for identifying diseases and healing. Altered states were also seen as important sources of artistic inspiration and a gateway to intuition and extrasensory perception. All other cultures have spent considerable time and energy developing various mind-altering techniques and have used them regularly in a variety of ritual contexts.

Michael Harner, a well-known anthropologist who also underwent a shamanic initiation in South America, pointed out that from a cross-cultural perspective, the traditional Western understanding of the human psyche is significantly flawed. It is ethnocentric in the sense that Western scientists view their own particular approach to reality and psychological phenomena as superior and “proven beyond a shadow of doubt,” while judging the perspectives of other cultures as inferior, naive, and primitive. Second, the traditional academic approach is also what Harner calls “cogni-centric,” meaning that it takes into consideration only those observations and experiences that are mediated by the five senses in an ordinary state of consciousness.3

The main focus of this book is to describe and explore the radical changes in our understanding of consciousness, the human psyche, and the nature of reality itself that become necessary when we pay attention to the testimony of non-ordinary states, as all other cultures before us. For this purpose, it does not make much difference whether the trigger of these states is the practice of meditation, a session in experiential psychotherapy, an episode of spontaneous psychospiritual crisis (“spiritual emergency”), a near-death situation, or ingestion of a psychedelic substance. Although these techniques and experiences may vary in some specific characteristics, they all represent different gateways into the deep territories of the human psyche, areas uncharted by traditional psychology. The thanatologist Kenneth Ring acknowledged this fact by coining for them the collective term Omega experiences.

Since we are interested here in exploring the most general implications of modern consciousness research for our understanding of ourselves and the universe, the examples that I use in this book are drawn from a variety of situations. Some come from sessions with Holotropic Breathwork™ or from psychedelic therapy, others from shamanic rituals, hypnotic regression, near-death situations, or spontaneous episodes of spiritual emergency. What they all have in common is that they represent a critical challenge to traditional ways of thinking and suggest an entirely new way of looking at reality and our existence.

The Adventure Begins: Throwing Open the Gates Beyond Everyday Reality

There are many different paths to our new understanding of consciousness. My own path started in Prague, the capitol of Czechoslovakia, soon after I finished high school in the late 1940s. At that time, a friend had loaned me Sigmund Freud’s Introductory Lectures to Psychoanalysis. I was deeply impressed by Freud’s penetrating mind and his ability to decode the obscure language of the unconscious mind. Within a few days after finishing Freud’s book I made the decision to apply to medical school, which was a necessary prerequisite to becoming a psychoanalyst.

During my medical school years I joined a small psychoanalytic group, led by three psychoanalysts who were members of the International Psychoanalytic Association, and volunteered my time at the psychiatric department of the Charles University School of Medicine. Later, I also underwent a training analysis by the former president of the Czechoslovakian Psychoanalytic Association.

The better acquainted I became with psychoanalysis, the more disillusioned I became. Everything I had read of Freud and his followers had offered what seemed to be convincing explanations of mental life. But these insights did not seem to carry over into the clinical work. I could not understand why this brilliant conceptual system did not offer equally impressive clinical results. Medical school had taught me that if I only understood a problem, I would be able to do something effective about it, or in the case of incurable diseases, see clearly the reason for my therapeutic limitations. But now I was being asked to believe that, even though we had a complete intellectual grasp of the psychopathology we were working with, we could do relatively little about it—even over an extremely long period of time.

About the same time that I was struggling with this dilemma, a package arrived at the department where I was working. It was from the Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland and contained samples of an experimental substance called LSD-25, which was said to have remarkable psychoactive properties. The Sandoz company was making the substance available to psychiatric researchers the world over who would study its effects and possible uses in psychiatry. In 1956 I became one of the early experimental subjects of this drug.

My first LSD session radically changed both my personal and professional life. I experienced an extraordinary encounter with my unconscious, and this experience instantly overshadowed all my previous interest in Freudian psychoanalysis. I was treated to a fantastic display of colorful visions, some abstract and geometrical, others filled with symbolic meaning. I felt an array of emotions of an intensity I had never dreamed possible.

This first experience with LSD-25 included undergoing special tests by a faculty member who was studying the effect of flashing lights on the brain. Prior to taking the psychedelic, I agreed to have my brain waves monitored by an electroencephalograph while lights of various frequencies were flashed before me.

During this phase of the experiment, I was hit by a radiance that seemed comparable to the light at the epicenter of an atomic explosion, or possibly to the supernatural light described in Oriental scriptures that appears at the moment of death. This thunderbolt of light catapulted me from my body. I lost all awareness of the research assistant, the laboratory, and any detail about my life as a student in Prague. My consciousness seemed to explode into cosmic dimensions.

I found myself thrust into the middle of a cosmic drama that previously had been far beyond even my wildest imaginings. I experienced the Big Bang, raced through black holes and white holes in the universe, my consciousness becoming what could have been exploding super-novas, pulsars, quasars, and other cosmic events.

There was no doubt in my mind that what I was experiencing was very close to experiences of “cosmic consciousness” I had read about in the great mystical scriptures of the world. In psychiatric handbooks such states were defined as manifestations of severe pathology. In the midst of it I knew that the experience was not the result of a psychosis brought on by the drug but a glimpse into a world beyond ordinary reality.

Even in the most dramatic and convincing depths of the experience I saw the irony and paradox of the situation. The Divine had manifested itself and had taken over my life in a modern laboratory in the middle of a serious scientific experiment conducted in a Communist country with a substance produced in the test tube of a twentieth-century chemist.

I emerged from this experience moved to the core. At that time I did not believe as I do today, that the potential for mystical experience is the birthright of all humans. I attributed everything I experienced to the drug itself. But there was no doubt in my mind that this substance was the “royal road into the unconscious.” I felt strongly that this drug could heal the gap between the theoretical brilliance of psychoanalysis and its lack of effectiveness as a therapeutic tool. It seemed that LSD-assisted analysis could deepen, intensify, and accelerate the therapeutic process.

In the following years, starting with my appointment to a position at the Psychiatric Research Institute in Prague, I was able to study the effects of LSD on patients with various emotional disorders, as well as on mental-health professionals, artists, scientists, and philosophers who had demonstrated serious motivations for such an experience. The research led to a deeper understanding of the human psyche, the enhancement of creativity, and the facilitation of problem solving.

During the early period of my research, I found my worldview undermined by daily exposure to experiences that could not be explained in terms of my old belief system. Under the unrelenting influx of incontrovertible evidence, my understanding of the world was gradually shifting from a basically atheistic position to a mystical one. What was first foreshadowed in my experience of cosmic consciousness had come to full fruition through careful daily examination of the research data.

In sessions of LSD-assisted psychotherapy, we witnessed a rather peculiar pattern. With low to medium dosages, subjects usually limited their experiences to reliving scenes from infancy and childhood. However, when the doses were increased or the sessions were repeated, each client sooner or later moved far beyond the realms described by Freud. Many of the experiences reported were remarkably like those described in ancient spiritual texts from Eastern traditions. I found this particularly interesting because most people reporting these experiences had no previous knowledge of the Eastern spiritual philosophies, and I certainly had not anticipated that such extraordinary experiential domains would become accessible in this way.

My clients experienced psychological death and rebirth, feelings of oneness with all humanity, nature, and the cosmos. They reported visions of deities and demons from cultures different from their own, or visits to mythological realms. Some reported “past life” experiences whose historical accuracy could later be confirmed. During their deepest sessions they were experiencing people, places, and things that they had never before touched with their physical senses. That is, they had not read, seen pictures of, or heard anyone talk of such things—yet they now experienced them as if they were happening in the present.

This research was a source of an endless array of surprises. Having studied comparative religions, I had intellectual knowledge about some of the experiences people were reporting. However, I had never suspected that the ancient spiritual systems had actually charted, with amazing accuracy, different levels and types of experiences that occur in non-ordinary states of consciousness. I was astonished by their emotional power, authenticity, and potential for transforming people’s views of their lives. Frankly, there were times that I felt deep discomfort and fear when confronted with facts for which I had no rational explanation and that were undermining my belief system and scientific worldview.

Then, as the experiences became more familiar to me, it became clear that what I was witnessing were normal and natural manifestations of the deepest domains of the human psyche. When the process moved beyond the biographical material from infancy and childhood and the experiences began to reveal the greater depths of the human psyche, with all its mystical overtones, the therapeutic results exceeded anything I had previously known. Symptoms that had resisted months or even years of other treatment often vanished after patients had experiences such as psychological death and rebirth, feelings of cosmic unity, archetypal visions, and sequences of what clients described as past-life memories.

At the Cutting Edge

Over three decades of systematic studies of the human consciousness have led me to conclusions that many traditional psychiatrists and psychologists might find implausible if not downright incredible. I now firmly believe that consciousness is more than an accidental by-product of the neurophysiological and biochemical processes taking place in the human brain. I see consciousness and the human psyche as expressions and reflections of a cosmic intelligence that permeates the entire universe and all of existence. We are not just highly evolved animals with biological computers embedded inside our skulls; we are also fields of consciousness without limits, transcending time, space, matter, and linear causality.

As a result of observing literally thousands of people experiencing non-ordinary states of consciousness, I am now convinced that our individual consciousnesses connect us directly not only with our immediate environment and with various periods of our own past, but also with events that are far beyond the reach of our physical senses, extending into other historical times, into nature, and into the cosmos. I can no longer deny the evidence that we have the capacity to relive the emotions and physical sensations we had during our passage through the birth canal and that we can re-experience episodes that took place when we were fetuses in our mothers’ wombs. In non-ordinary states of consciousness, our psyches can reproduce these situations in vivid detail.

On occasion, we can reach far back in time and witness sequences from the lives of our human and animal ancestors, as well as events that involved people from other historical periods and cultures with whom we have no genetic connection whatsoever. Through our consciousnesses, we can transcend time and space, cross boundaries separating us from various animal species, experience processes in the botanical kingdom and in the inorganic world, and even explore mythological and other realities that we previously did not know existed. We might discover that experiences of this kind will profoundly influence our life philosophy and worldview. We will very likely find it increasingly difficult to share the belief system dominating the industrial cultures and the philosophical assumptions of traditional Western science.

Having started this research as a convinced materialist and atheist, I had to open myself to the fact that the spiritual dimension is a key factor in the human psyche and in the universal scheme of things. I feel strongly that becoming aware of this dimension of our lives and cultivating it is an essential and desirable part of our existence; it might even be a critical factor for our survival on this planet.

An important lesson I have learned from the study of non-ordinary states of consciousness is the recognition that many conditions mainstream psychiatry considers bizarre and pathological are actually natural manifestations of the deep dynamics of the human psyche. In many instances, the emergence of these elements into consciousness may be the organism’s effort to free itself from the bonds of various traumatic imprints and limitations, heal itself, and reach a more harmonious way of functioning.

Above all, consciousness research over the past three decades has convinced me that our current scientific models of the human psyche cannot account for many of the new facts and observations in science. They represent a conceptual straitjacket and render many of our theoretical and practical efforts ineffective and, in many instances, even counterproductive. Openness to new data challenging traditional beliefs and dogmas has always been an important characteristic of the best of science and a moving force of progress. A true scientist does not confuse theory with reality and does not try to dictate what nature should be like. It is not up to us to decide what the human psyche can do and what it can not do to fit our neatly organized preconceived ideas. If we are ever to discover how we can best cooperate with the psyche, we have to allow it to reveal its true nature to us.

It is clear to me that we need a new psychology, one that is more in alignment with the findings of modern consciousness research, one that complements the image of the cosmos we are beginning to envision through the most recent discoveries in the physical sciences. To investigate the new frontiers of consciousness, it is necessary to go beyond the traditional verbal methods for collecting relevant psychological data. Many experiences originating in farther domains of the psyche, such as mystical states, do not lend themselves to verbal descriptions; throughout the ages, the spiritual traditions have referred to them as “ineffable.” So it stands to reason that one has to use approaches that allow people to access deeper levels of their psyches without having to depend on language. One of the reasons for this strategy is that much of what we experience in the deeper recesses of our minds are events that occurred before we developed our verbal skills—in the womb, at birth, and in early infancy—or are non-verbal by their very nature. All of this suggests the need to develop brand new research projects, exploratory tools, and methodologies for discovering the deepest nature of the human psyche and the nature of reality.

The information in this book is drawn from many thousands of non-ordinary experiences of various kinds. Most of them were holotropic and psychedelic sessions I have conducted and witnessed in the United States, Czechoslovakia, and during my travels; others were sessions run by colleagues who shared their observations with me. In addition, I have also worked with people in psychospiritual crises and have, over the years, personally experienced a number of non-ordinary states of consciousness in experiential psychotherapy, psychedelic sessions, shamanic rituals, and meditation. During the month-long seminars that my wife, Christina, and I conducted at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, we had an extremely rich exchange with anthropologists, parapsychologists, thanatologists, psychics, shamans, and spiritual teachers, many of whom are now close friends of ours. They have helped me enormously to see my own findings in a broad interdisciplinary and cross-cultural context.

The key experiential approach I now use to induce non-ordinary states of consciousness and gain access to the unconscious and superconscious psyche is Holotropic Breathwork™, which I have developed jointly with Christina over the last fifteen years. This seemingly simple process, combining breathing, evocative music and other forms of sound, body work, and artistic expression, has an extraordinary potential for opening the way for exploring the entire spectrum of the inner world. We are currently conducting a comprehensive training program and have certified several hundreds of practitioners who are now offering workshops in different parts of the world. Those readers who will become seriously interested in the avenues described in this book should thus have no difficulty in finding opportunities to explore them experientially in a safe context and under expert guidance.

My material is drawn from over 20,000 Holotropic Breathwork™ sessions with people from different countries and from all walks of life, as well as 4,000 psychedelic sessions that I conducted in the earlier phases of my research. Systematic study of non-ordinary states has shown me, beyond any doubt, that the traditional understanding of the human personality, limited to postnatal biography and to the Freudian individual unconscious, is painfully narrow and superficial. To account for all the extraordinary new observations, it became necessary to create a radically expanded model of the human psyche and a new way of thinking about mental health and disease.

In the following chapters, I will describe the cartography of the human psyche that has emerged from my study of non-ordinary states of consciousness and that I have found very useful in my everyday work. In this cartography I map out paths through various types and levels of experience that have become available in certain special states of mind and that seem to be normal expressions of the psyche. Besides the traditional biographical level containing material related to our infancy, childhood, and later life, this map of the inner space includes two additional important domains: (1) The perinatal level of the psyche, which, as its name indicates, is related to our experiences associated with the trauma of biological birth, and (2) the transpersonal level, which reaches far beyond the ordinary limits of our body and ego. This level represents a direct connection between our individual psyches, the Jungian collective unconscious, and the universe at large.

When I initially became aware of these territories during my early research, I thought I was creating a new map of the psyche that was made possible by the discovery of a revolutionary tool, LSD. As this work continued, it became very clear to me that the emerging map was not new at all. I realized that I was rediscovering ancient knowledge of human consciousness that has been around for centuries or even millennia. I started seeing important parallels with shamanism, with the great spiritual philosophies of the East, such as different systems of yoga, various schools of Buddhism or Taoism, with the mystical branches of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and with many other esoteric traditions of all ages.

These parallels between my research and ancient traditions provided a convincing modern validation of the timeless wisdom that philosopher and writer Aldous Huxley called “perennial philosophy.” I saw that Western science, which in its juvenile hubris rejected and ridiculed what the ancients had to offer, must now revise its premature judgment in view of these new discoveries. I hope that the old/new cartography described in this book will prove useful as a guide for those who decide to venture into the farther reaches of the human psyche and explore the frontiers of consciousness. Although each inner journey is unique and varies in details, all of them also show significant similarities and certain general landmarks. It can be useful and comforting as we are entering territories that are new and potentially terrifying to find out that many other people have safely traveled through them before.

Unveiling the Mysteries of Infancy and Childhood

The realm of the psyche that is usually the first to emerge in experiential therapy is the recollective or biographical level, where we find memories from our infancy and childhood. It is generally accepted in modern depth psychology that our present emotional life is, to a great extent, shaped by events from the “formative” years of our lives, that is, the years before we learned how to articulate our thoughts and feelings. The quality of mothering we received, the family dynamics, the traumatic and nourishing experiences we had at that time, play important roles in shaping our personalities.

The biographical realm is generally the easiest part of the psyche to access, and it is certainly the part with which we are most familiar. However, not all the important events from our early lives can be reached by everyday methods of recall. It may be easy to remember happy times, but the traumas at the roots of our fears and self-doubts have a way of eluding us. They sink deep into the region of our psyches that has come to be known as the “individual unconscious” and are hidden from us by a process that Sigmund Freud called “repression.” Freud’s pioneering work revealed that it was possible to gain access to the unconscious and free ourselves from repressed emotional material through the systematic analysis of dreams, fantasies, neurotic symptoms, slips of the tongue, daily behaviors, and other aspects of our lives.

Freud and his followers probed the unconscious mind through “free association.” This is a technique with which most people are familiar. We are asked to say whatever comes to mind for us, allowing words, mental images, and memories to flow freely, without censoring them in any way. This technique, as well as other exclusively verbal approaches, proved to be a relatively weak exploratory tool. Then, in the middle of this century, a new discipline, called “humanistic psychology,” produced a variety of therapies that utilized “body work” and encouraged the full expression of emotions within the safety of a therapeutic setting. These “experiential” approaches increased the effectiveness of the exploration of biographical material. However, like earlier verbal techniques these new approaches were conducted in ordinary states of consciousness.

The therapeutic use of non-ordinary states, which we explore in this book, sheds new light on biographical material. While this work with non-ordinary states confirms much that is already known through traditional psychotherapy, it swings open the gates to vast new possibilities, providing us with information about the nature of our lives that is quite revolutionary. In psychoanalysis and related approaches, core memories that have been repressed from infancy and childhood may take months or even years to reach. In work with non-ordinary states, such as that in Holotropic Breathwork™, significant biographical material from our earliest years frequently starts coming to the surface in the first few sessions. Not only do people gain access to memories of their childhood and infancy, they often vividly connect with their births and their lives within the womb and begin venturing into a realm of experience even beyond these.

There is an additional advantage to this work. Instead of simply remembering early events in our lives, or reconstructing them from bits and pieces of dreams and memories, in non-ordinary states of consciousness we can literally relive early events from our lives. We can be two months old, or even younger, once again experiencing all the sensory, emotional, and physical qualities as we first knew them. We experience our bodies as infants, and our perceptions of the circumstances are primitive, naive, and childlike. We see it all with unusual vividness and clarity. There is good reason to believe that these experiences reach all the way back to the cellular level.

During experiential sessions in Holotropic Breathwork™, it is amazing to witness the depth to which people are able to go as they relive the earliest experiences of their lives. It is not unusual to see them change in appearance and demeanor in a way that is age-appropriate for the period they are experiencing. People who regress to infancy typically adopt facial expressions, body postures, gestures, and behavior of small children. In early infancy experiences this includes salivation and automatic sucking movements. What is even more remarkable is that they usually manifest neurological reflexes that are also age-appropriate. They might show a sucking reflex to a light touch of the lips and other so-called axial reflexes that characterize the normal neurological responses of infants.

One of the most dramatic findings was a positive Babinski sign occurring in people regressed to early childhood states. To elicit this reflex, which is part of the pediatrician’s neurological test, the sole of the foot is touched with a sharp object. In infants the toes fan out in response to this stimulus; in older children they curl in. The same adults who showed a fanning out reaction to this test during the time that they were regressed to infancy reacted normally while reliving periods of later childhood. And, as expected, the same people displayed normal Babinski responses when they returned to normal consciousness states.

There is another important difference between exploring the psyche in non-ordinary states and doing so in ordinary states. In non-ordinary states there is an automatic selection of the most relevant and emotionally charged material from the person’s unconscious. It is as if an “inner radar” system scans the psyche and the body for the most important issues and makes them available to our conscious minds. This is invaluable for therapist and client alike, saving us the task of having to make a decision about which issues that arise from our unconscious are important and which are not. Such decisions are typically biased because they are often influenced by our personal belief systems and training in one of the many schools of psychotherapy, which disagree with one another.

This radar function found in non-ordinary states of consciousness has revealed aspects of the biographical realm that had previously eluded us in our exploration of human consciousness. One of these discoveries involves the impact of early physical trauma on our emotional development. We found that the radar system brings to the surface not only memories of emotional traumas, but also memories of events where the survival or integrity of the physical body was threatened. The release of emotions and patterns of tension that were still being stored in the body as a result of these early traumas proved to be one of the most immediate and valuable benefits derived from this work. Problems associated with breathing, such as diphtheria, whooping cough, pneumonia, or near drowning, played particularly critical roles.

Traditional psychiatry sees physical traumas such as these as potentially contributing to organic brain damage, but it fails to acknowledge their immense impact on an emotional level. People who experientially relive memories of serious physical traumas come to fully recognize the scars these events left on their psyches. They also recognize the powerful contribution of these traumas to present difficulties with psychosomatic diseases such as asthma, migraine headaches, depression, phobias, or even sadomasochistic tendencies. In turn, reliving these early traumas and working them through frequently has a therapeutic effect, bringing either temporary or permanent relief from symptoms and a sense of well-being that the person never dreamed was possible.

COEX Systems—Keys to Our Destiny

Another important discovery of our research was that memories of emotional and physical experiences are stored in the psyche not as isolated bits and pieces but in the form of complex constellations, which I call COEX systems (for “systems of condensed experience”). Each COEX system consists of emotionally charged memories from different periods of our lives; the common denominator that brings them together is that they share the same emotional quality or physical sensation. Each COEX may have many layers, each permeated by its central theme, sensations, and emotional qualities. Many times we can identify individual layers according to the different periods of the person’s life.

Each COEX has a theme that characterizes it. For example, a single COEX constellation can contain all major memories of events that were humiliating, degrading, or shameful. The common denominator of another COEX might be the terror of experiences that involved claustrophobia, suffocation, and feelings associated with oppressing and confining circumstances. Rejection and emotional deprivation leading to our distrust of other people is another very common COEX motif. Of particular importance are systems involving life-threatening experiences or memories where our physical well-being was clearly at risk.

It is easy to jump to the conclusion that COEX systems always contain painful material. However, a COEX system can just as well contain constellations of positive experiences, experiences of tremendous peace, bliss, or ecstasy that have also helped to mold our psyches.

In the earliest stages of my research, I believed that COEX systems primarily governed that aspect of the psyche known as the individual unconscious. At that time I was still working under a premise I had learned in my training as a psychiatrist—that the psyche was entirely the product of our upbringing, that is, of the biographical material we stored within our minds. As my experiences with non-ordinary states expanded, becoming richer and more extensive, I realized that the roots of COEX systems reached much deeper than I ever could have imagined.

Each COEX constellation appears to be superimposed over and anchored into a very particular aspect of the birth experience. As we will explore in the next chapters of the book, the experiences of birth, so rich and complex in physical sensations and emotions, contain the elementary themes for every conceivable COEX system. In addition to these perinatal components, typical COEX systems can have even deeper roots. They can reach farther into prenatal life and into the realm of transpersonal phenomena such as past life experiences, archetypes of the “collective unconscious,” and identification with other life forms and universal processes. My research experience with COEX systems has convinced me that they serve to organize not only the individual unconscious, as I originally believed, but the entire human psyche itself.

COEX systems affect every area of our emotional lives. They can influence the way we perceive ourselves, other people, and the world around us. They are the dynamic forces behind our emotional and psychosomatic symptoms, setting the stage for the difficulties we have relating to ourselves and other people. There is a constant interplay between the COEX systems of our inner world and events in the external world. External events can activate corresponding COEX systems within us. Conversely, COEX systems help shape our perceptions of the world, and through these perceptions we act in ways that bring about situations in the external world that echo patterns in our COEX systems. Put another way, our inner perceptions can function like complex scripts through which we re-create core themes of our own COEX systems in the external world.

The function of COEX systems in our lives can best be illustrated through the story of a man I will call Peter, a thirty-seven-year-old tutor who was intermittently treated at our department in Prague without success prior to his undergoing psychedelic therapy. His experiences, growing out of a very dark period in world history, are dramatic, graphic, and bizarre. For this reason the reader may find the example unpleasant. However, his story is valuable in the context of our present discussion because it so clearly reveals the dynamics of COEX systems and how it is possible to emotionally liberate ourselves from those systems that cause us pain and suffering.

At the time we began with the experiential sessions, Peter could hardly function in his everyday life. He was obsessed with the idea of finding a man of a certain physical appearance, preferably clad in black. He wanted to befriend this man and tell him of his urgent desire to be locked in a dark cellar and exposed to physical and mental torture. Often unable to concentrate on anything else, he wandered aimlessly through the city, visiting public parks, lavatories, bars, and railroad stations in search of the “right man.”

He succeeded on several occasions in persuading or bribing men who met his criteria to carry out his wishes. Having a special gift for finding people with sadistic traits, he was twice almost killed, seriously hurt several times, and once robbed of all his money. On those occasions when he was successful in achieving the experience he craved, he was extremely frightened and genuinely disliked the torture he underwent. Peter suffered from suicidal depressions, sexual impotence, and occasional epileptic seizures.

As we went over his personal history, I discovered that his problems started at the time of his compulsory employment in Germany during World War II. As the citizen of a Nazi occupied territory, he was forced into what amounted to slave labor, performing very dangerous work. During this period of his life, two SS officers forced him at gunpoint to engage in their homosexual practices. When the war was over and Peter was finally released, he found that he continued to seek homosexual intercourse in the passive role. This eventually included fetishism for black clothes and finally evolved into the full scenario of the obsession already described.

In his effort to come to terms with his problem, Peter underwent fifteen consecutive sessions in psychedelic therapy. In the process an important COEX system surfaced, providing us with the key for an eventual resolution. In the most superficial layers of this particular COEX, we predictably discovered Peter’s more recent traumatic experiences with his sadistic partners.

A deeper layer of the same COEX system contained Peter’s memories from the Third Reich. In his experiential sessions he relived his terrifying ordeals with the SS officers and was able to begin resolving the many complex feelings surrounding those events. In addition, he relived other traumatic memories of the war and dealt with the entire oppressive atmosphere of that horrible period in history. He had visions of pompous Nazi military parades and rallies, banners with swastikas, ominous giant eagle emblems, and scenes from concentration camps, to name just a few.

Following these revelations, Peter entered an even deeper layer of this COEX system where he began re-experiencing scenes from his childhood. He had often been brutally punished by his parents, particularly by his alcoholic father who became violent when he was drunk, often beating Peter with a large leather strap. His mother often punished him by locking him in a dark cellar without food or water for hours at a time. Peter could not remember her wearing anything but black dresses. At this point, he recognized the pattern of his obsession—he seemed to crave all the elements of punishment that had been inflicted on him by his parents.

Peter’s experiential exploration of his key COEX system continued. He relived his own birth trauma. Vivid memories of this time—once again focused on biological brutality—revealed themselves to him as the basic pattern, or model, for all those elements of sadistic experience that seemed to predominate in his life thereafter. His attention was clearly focused on dark enclosed spaces, confinement and restriction of his body, and exposure to extreme physical and emotional torture.

As Peter relived his birth trauma he began to experience freedom from his obsessions, as if having finally located the primary source of this particular COEX system he could begin to dismantle it. He eventually was able to enjoy relief from his difficult symptoms and begin functioning in his life.

While the discovery of the psychological importance of physical traumas has added important new dimensions to the broad biographical realm of the psyche, this work is still addressed primarily to a territory that is accepted and well known in traditional psychology and psychiatry. But my own as well as others’ research with non-ordinary states of consciousness has led us into vast new territories of the psyche that Western science and traditional psychology have only begun to explore. The open-minded, systematic exploration of these realms could have far-reaching consequences not only for human consciousness research and psychiatry but also for the philosophy of science and the entire Western culture.4

Journeys Inward: Farther Reaches of Consciousness

When working in non-ordinary states of consciousness the amount of time that people spend exploring early childhood varies greatly. However, if they continue to work in non-ordinary states, they sooner or later leave the arena of individual history following birth and move to entirely new territories. While these new territories have not yet been recognized by Western academic psychiatry, they are not, by any means, unknown to humanity. On the contrary, they have been systematically studied and held in high esteem by ancient and pre-industrial cultures since the dawn of human history.

As we venture beyond the biographical events of early childhood, we enter into a realm of experience associated with the trauma of biological birth. Entering this new territory, we start experiencing emotions and physical sensations of great intensity, often surpassing anything we might consider humanly possible. Here we encounter emotions at two polar extremes, a strange intertwining of birth and death, as if these two aspects of the human experience were somehow one. Along with a sense of life-threatening confinement comes a determined struggle to free oneself and survive.

Because most people identify this experience with biological birth trauma, I refer to it as the perinatal realm of the psyche. This term is a Greek-Latin word composed of the prefix peri- meaning “near” or “around,” and the root word natalis, “pertaining to childbirth.” The word perinatal is commonly used in medicine to describe biological processes occurring shortly before, during, and immediately after birth. However, since traditional medicine denies that the child has the capacity to record the experiences of birth in its memory, this term is not used in traditional psychiatry. The use of the term perinatal in connection with consciousness reflects my own findings and is entirely new.

Exploration in non-ordinary states of consciousness has provided convincing evidence that we do store memories of perinatal experiences in our psyches, often at a deep cellular level. People with no intellectual knowledge of their births have been able to relive, with extraordinary detail, facts concerning their births, such as the use of forceps, breech delivery, and the mother’s earliest responses to the infant. Time and time again, details such as these have been objectively confirmed by questioning hospital records or adults who were present at the delivery.

Perinatal experiences involve primitive emotions and sensations such as anxiety, biological fury, physical pain, and suffocation, typically associated with the birth process. People reliving birth experiences also usually manifest the appropriate physical movements, positioning their arms and legs, and twisting their bodies in ways that accurately re-create the mechanics of a particular type of delivery. We can observe this even with people who have neither studied nor observed the birth process in their adult lives. Also, bruises, swellings, and other vascular changes can unexpectedly appear on the skin in the places where forceps were applied, where the wall of the birth canal was pressing on the head, or where the umbilical cord was constricting the throat. All these details can be confirmed if good birth records or reliable personal witnesses are available.

These early perinatal experiences are not limited to the delivery process of childbirth. Deep perinatal memories can also provide us with a doorway into what Jung called the collective unconscious. While reliving the ordeal of passing through the birth canal we may identify with those same events experienced by people of other times and other cultures, or even identify with the birth process experienced by animals or mythological figures. We can also feel a deep link with all those who have been abused, imprisoned, tortured, or victimized in some other way. It is as if our own connection with the universal experience of the fetus struggling to be born provides us with an intimate, almost mystical connection with all beings who are now or ever have been in similar circumstances.

Perinatal phenomena occur in four distinct experiential patterns, which I call the Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPMs). Each of the four matrices is closely related to one of the four consecutive periods of biological delivery. At each of these stages, the baby undergoes experiences that are characterized by specific emotions and physical feelings; each of these stages also seems to be associated with specific symbolic images. These come to represent highly individualized psychospiritual blueprints that guide the way we experience our lives. They may be reflected in individual and social psychopathology or in religion, art, philosophy, politics, and other areas of life. And, of course, we can gain access to these psychospiritual blueprints through non-ordinary states of consciousness, which allow us to see the guiding forces of our lives much more clearly.

The first matrix, BPM I, which can be called the “Amniotic Universe,” refers to our experiences in the womb prior to the onset of delivery. The second matrix, BPM II, or “Cosmic Engulfment and No Exit,” pertains to our experiences when contractions begin but before the cervix opens. The third matrix, BPM III, the “Death and Rebirth Struggle,” reflects our experiences as we move through the birth canal. The fourth and final matrix, BPM IV, which we can refer to as “Death and Rebirth,” is related to our experiences when we actually leave the mother’s body. Each perinatal matrix has its specific biological, psychological, archetypal, and spiritual aspects.

In the following four chapters, we will explore the perinatal matrices as they would naturally unfold during childbirth. Each chapter begins with a personal narrative describing experiences that are characteristic of that matrix, then discusses the biological basis for the experience, how that experience becomes translated into a specific symbolism within our psyches, and how that symbolism affects our lives.

It should probably be noted that in experiential self-exploration, we do not necessarily experience the individual matrices in their natural order. Instead, perinatal material is selected by our own inner radar systems, making the order in which each person accesses this material highly individualized. Nevertheless, for the sake of simplicity it is useful to think about them in the order of the following four chapters.