It is said, with some justification perhaps, that most Maltese are superstitious, and a traditional wariness about things unknown is an important facet of the national character. This may not be so true today, but in days when there were fewer outside influences to distract, such as television, the cinema and the internet, everyone knew what brought good luck or bad luck. This was particularly noticeable away from sophisticated town society but, even there, many a mother would never tempt fate by wearing green the day her child was to sit an important exam.

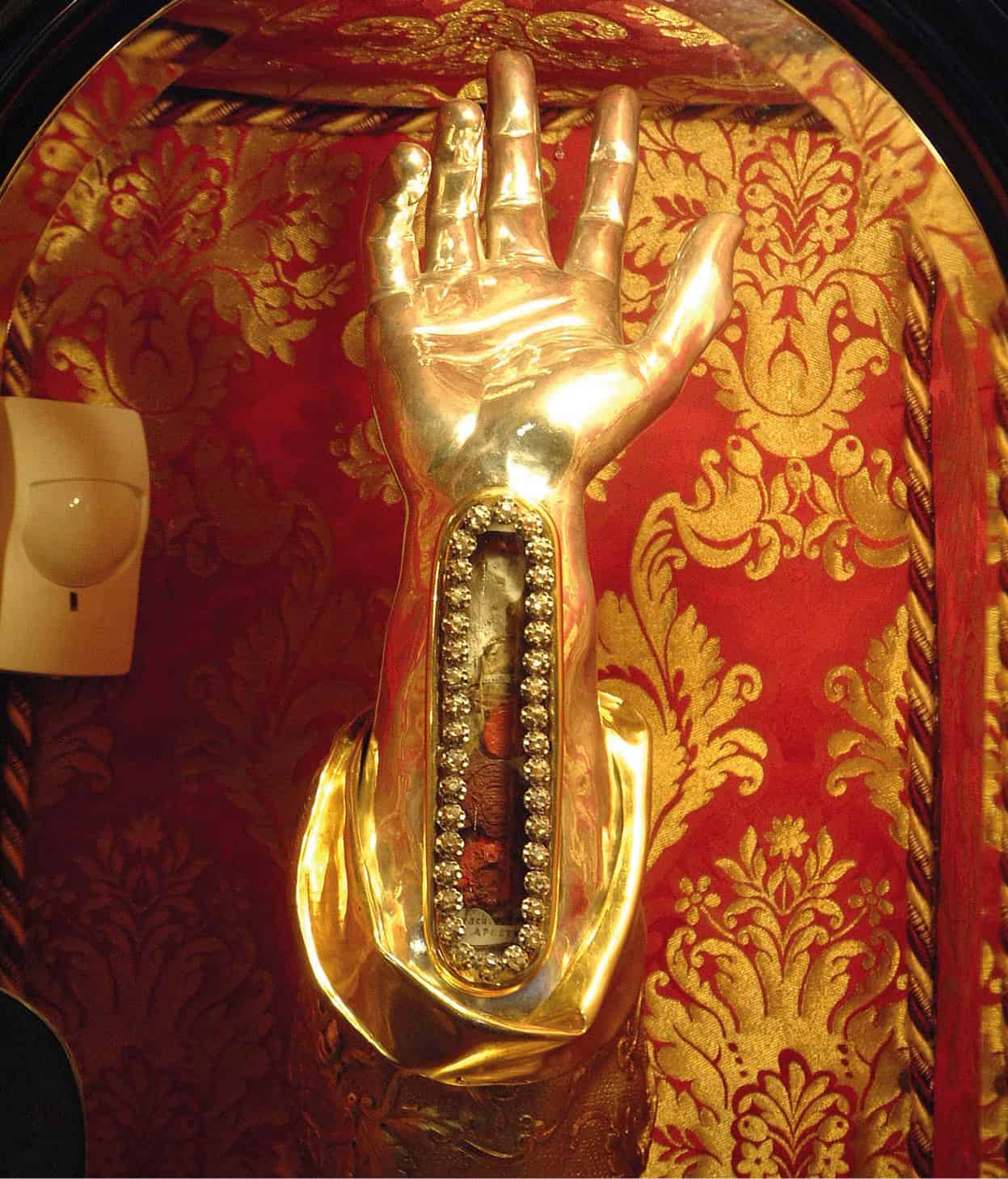

Holy reliquary at St Paul Shipwreck Church.

Viewing Malta

According to tradition, it is good luck to have a baby on St Mary’s Day, which falls during the month of August. In fact, folklore goes so far as to suggest that a baby born on this day will grow up to become a talented horse racer!

Saints preserve us

Much superstition is handed down through families and much has a religious slant to it. For instance, university students may make their promises to St Jude, patron saint of students, for luck.

St Rita, St Anthony and the Virgin Mary are equally popular. In Gozo’s Ta’ Pinu Sanctuary, a corridor is devoted to paintings of shipwrecked sailors saved by the Virgin Mary, as well as macabre remembrances of other miraculous cures after invoking her name – such as gallstones in jam jars, discarded crutches and babies’ trusses.

Ta’ Pinu shrine.

Malta Tourism Authority

God and the devil

Religious shrines are also commonplace. Until recently, it was the norm for bus drivers to craft a little shrine to their chosen patron saint close to the front seat; the modern fleet doesn’t allow for it. Nevertheless, older passengers will still make the sign of the cross before a journey.

Meanwhile, to deter the devil, churches have two clocks in their towers, one real, the other a trompe l’oeil. Tradition says the devil is confused by two clocks and so cannot come to collect departing souls.

Warding off evil in a more overtly pagan manner, many houses in rural communities have bulls’ horns tied, points outwards, on the highest corner of a roof or perhaps above the front door. Many, trying to get the best of both protections, attach horns on one corner and a saint’s effigy on another.

Maltese folklore suggests that an egg laid on Lady Day (25 March) possesses special healing properties. As a result, they were left to harden until their contents turned into a balsam-like texture that was used to remedy all sorts of wounds.

In the 18th century, young girls in society were given simple coral necklaces to ward off evil and, until recently, many men wore tiny amulets shaped like a horn on a chain around the neck. In the old Latin tradition, many still make the qrun, that is, point the fore- and little finger of the hand like bulls’ horns, to ward off the evil eye or to wish someone ill.

Keeping an eye open

Since bad luck is not confined to humans, the luzzu and dghajsa – the beautiful, brightly coloured traditional boats, which have been used by Maltese sailors since Phoenician times – have their protection, too. Each boat may be named after a Catholic saint, but each also has, on either side of its prow, the wide-open, ever-alert eye of Osiris, one of the most important of the Ancient Egyptian gods, ready to ward off the worst.

In a similar effort to ward off evil, horses puling carts, or karrozin, often have red tassels or feathers attached to their harness or bridle.

Old wives and young mothers

Many old beliefs have faded away, but old wives’ tales still abound. It has always been deemed that the best months for marriage are January, April and August, when bodies are most fertile; that women should not work in fields during menstruation or the produce will be ruined; that black underwear ensures pregnancy, white the opposite; and, if a pregnant woman craves a particular food and does not eat it, her child will have a birthmark in that shape.

Although much less so today, young mothers are especially wary of the evil eye. It may be possessed by a woman who does not know that she has it. And if she should say to a mother, “What a beautiful baby you have”, then the next day the child will develop spots, a cold or a squint. The baby has been “given the eye”.

Tradition and superstitious rituals play a big part in Maltese weddings.

Malta Tourism Authority

The ever-watchful eye of Osiris brings good luck to luzzus.

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Life and death

An enjoyable custom often takes place on a child’s first birthday, when the family gets together for what is known as the quccija. They assemble a tray of small objects for the child to choose from, varying them slightly for a boy or girl. Among them might be a thimble, pen, rosary, egg, a computer mouse and some money. The object chosen foretells the child’s future – as a tailor, clerk, priest, farmer, IT consultant, banker, etc. It used to be said that if you did not carry out this ritual, your child would not succeed in life; nowadays, it is just an excuse for a party.

Another Catholic home ritual mimics the pagan celebration of rebirth. Two weeks before the Christmas crib is assembled, a child is given bowls in which to sow seeds of wheat. The seedlings are kept in the dark and watered every two days. As soon as the shoots begin to sprout, the bowls are put near the figure of the baby Jesus.

On a sadder note, if a family member should die at home, a glass of water or a saucer of salt must be placed near the front door. The spirit must never leave the house thirsty or without salt to flavour its food.