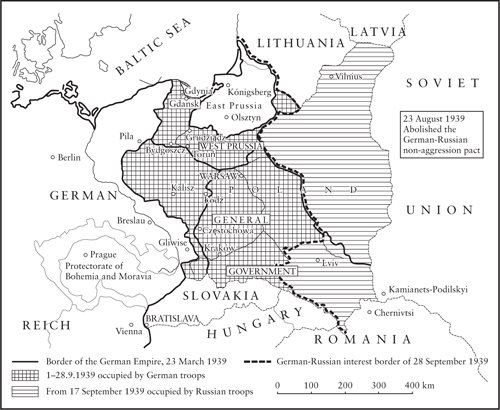

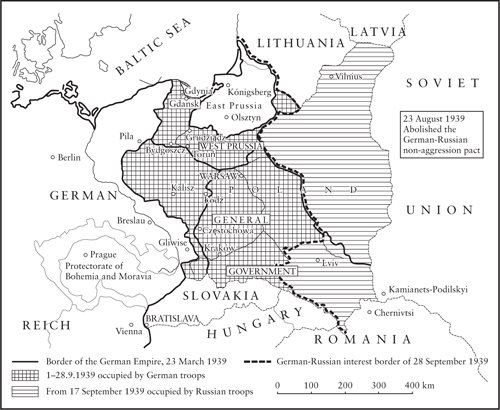

The annexation and partitioning of Polish national territory after the end of German-Polish and Polish-Soviet conflicts. [The last Polish field troops on 6 October 1939].

Following the negative experience of Warsaw Father did not hesitate long over his deliberations in an entirely different direction. Envoy Schmidt (Press) recounts the scene in the special train of the return trip in detail:230

‘On 27 January Ribbentrop was in no way convinced that the negotiations were to be seen as having definitively failed, although he was very pessimistic about them …

‘I was all the more surprised when during the return trip the Foreign Minister called me into his saloon car to deliver the press report and after some brief introductory words, in the presence of Mme Ribbentrop asked me the precise question:

‘“Do you believe there is a possibility of reaching a German-Soviet cooperation?”

‘I must have looked very nonplussed, for Mme von Ribbentrop laughed and said to her husband: “Dr Schmidt is quite scared”, whereupon the Minister quickly added: “In politics, as in a General Staff, one has to examine all the possibilities, also this one which is naturally a purely theoretical question. And you have after all often told me that you have occupied yourself intensively with the history of the German-Russian cooperation after World War One.”

‘Ribbentrop was thereby alluding to my penchant, well known to him, for the chapter in history of German-Soviet relations between 1918 and 1933 …

‘I therefore joked about his question in the saloon car, saying: “It might be difficult for Stalin to associate himself with the anti-Comintern pact.” I was left almost speechless when the quick-witted Mme von Ribbentrop retorted: “Why not, if it is renamed?”

‘It was instantly clear to me that Ribbentrop was evidently very seriously occupied with the question of a German-Soviet settlement … ‘Walter Hewel also came into the saloon car and joined in the discussion. In the course of it Ribbentrop’s train of thought became fairly clear: he had evidently been convinced by the last talks with Moltke [German ambassador in Warsaw] that the resistance of the Poles to a close collaboration with Germany was indeed greater that he had thought and no longer saw a real chance of a solution for Danzig or a greater bonding of Poland to the Reich to build up the deployment area231 against the Soviet Union. The consequence of this realization presented itself as an urgency for … [the] Foreign Minister.

‘If Poland could not be drawn into the German sphere of interest with the tacit consent of France, then Warsaw would have to be manoeuvred back into its old German-Russian dilemma on the horns of which Piłsudski had always evinced such panic and fear that he had made the undertaking of preventing a German-Russian collaboration in some way a political testament for the Polish diplomacy.’

Hewel’s inclusion in this discussion is noteworthy. Hewel was an old comradein-arms of Hitler’s, having taken part in the ‘March on the Feldherrnhalle’ in the putsch in Munich in 1923 and then spent many years in South-East Asia. I was there in London to see how Hewel cleaved to Father, to become in the end Father’s or the Auswärtiges Amt’s permanent representative to Hitler. Presumably Hewel was now brought in for him to be made aware from the start of the thoughts with which Father now had to attempt to ‘turn around’ Hitler from his anti-Bolshevik stance to a ‘pro-Russian’ line, something that without any doubt would be extraordinarily difficult. Hitler had entered politics with the maxim: War on Marxism, Communism, Bolshevism. I have depicted his concept of foreign policy – which he had consistently pursued since his access to Government – step by step. The fundamental principle of the German policy was the organization of Eastern Europe for defence against the aggressive Russian Bolshevism. Now his Foreign Minister was attributing to him a 180-degree volte-face and his associating with the Devil. In 1933, shortly after his access to government, Hitler had said to Nadolny, the German ambassador in Moscow: ‘I will have nothing to do with these people.’232

Had his Foreign Minister, this very Ribbentrop, ever taken part in the fierce street and demonstration battles against the Communists? Had he not, as he himself had declared to Hitler, been a party-supporter of Stresemann’s for many years? Did he not, accordingly, come from that bourgeois milieu to which Hitler did not attribute the capacity and above all the preparedness to acknowledge the worldview dimension of his fight against Bolshevism, not to speak of endowing the fight with the necessary harshness? In these circumstances it could occasionally be beneficial if a ‘veteran’ such as Hewel were to drop an appropriate word at the right moment, here in the sense of a – in Father’s eyes – necessary ‘turnaround’ in German policy.

I first heard about these fundamental new concepts regarding German foreign policy in the few days I was able to spend at home between obtaining my Abitur and commencing Labour Service. Mother had had another operation on her frontal sinus, this time in Kiel. For some reason of protocol she had to be present in Berlin shortly after the operation, to be on hand, and was therefore fetched from Kiel by air. I took the opportunity to be on the flight with her so as to report on my having successfully passed my Abitur. I was received with the words ‘if we crash, you’ll still beforehand have your ears boxed!’ (In the slight Mainz accent Mother sometimes adopted when she was agitated.) She was joking, of course, but it displeased her very much if family members were in the same airplane without sufficient reason.

The flight was an opportunity for a thorough discussion of the political situation; my parents’ visit to Warsaw was just a few weeks since. The first thing Mother spoke about was Stalin’s ‘Chestnut Speech’. On 10 March 1939, in a speech to the Party Congress, Stalin had said that certain ‘powers’ should not think that the Soviet Union would ‘pull the chestnuts out of the fire’ for them. Stalin could unmistakably be interpreted as meaning that the Soviet Union would not permit itself to be embroiled in direct confrontation with Germany for the sake of the Western powers. The formulation could be a signal sent to Germany, but not necessarily so and could instead be a tactical move in the direction of the Western Allies. I gathered from Mother’s report that Father was ready to put the Russians to the test. The possibility seemed to present itself here to break the deadlock and thereby avoid the mistakes of imperial policy before the First World War. Mother, however, also pointed out the difficulties there would be in moving Hitler to approve such a policy. I was impressed beyond all measure.

I had – sometimes in close proximity – experienced the efforts made over so many years to obtain Britain’s amity. During the weekend excursions with my parents I have described, Father used to speak of the liability burdening his efforts resulting from the calamitous Spanish ‘non-involvement committee’. German-English relations were the pivot around which everything turned. I had registered in my inner self the disappointments of the German side. Not to be forgotten was the article written by the London correspondent of the Berliner Lokalanzeiger, von Kries, under the headline ‘Test-run Mobilization’ on British policy during the ‘May Crisis’, that came to the unequivocal conclusion that Britain was preparing for war with the Reich. The altered atmosphere in England that I had already sensed at the time of our exchange visit to Bath could not be overlooked. Bismarck’s policy of ‘reinsurance’ through an agreement with Russia was familiar to me. Its non-renewal by German Reich Chancellor Caprivi in 1890 was almost a ‘hobbyhorse’ of Grandfather Ribbentrop’s. However, the Pan-Slavic movement had also existed in tsarist Russia, directing a particularly aggressive impact against the West, that was widely supported by circles in Moscow and St Petersburg. But it was precisely because of the Soviet Union’s potential that it was worth striving for – indeed necessary – so as to take the pressure off in that direction. Germany had to opt for the West, and if such an option was not open, then it would have to be for the East. Some time later I heard from Mother that the Russian government was said to have been absolutely cooperative in the technical processing of Russian diplomatic representations in Czechoslovakia following the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. According to Father’s estimate this detail could signify a renewed signal.

Naturally, Mother and I also talked about the establishment of the Protectorate. Mother seemed to me to be very thoughtful on this point and said nothing when I told her about the subject of my Abitur essay. Father too remained very serious and silent when this subject came up. After Munich the circumstances in Resttschechei (remainder of Czechoslovakia) had in no way been consolidated, quite to the contrary. The various populations now also wanted their independence; they were diverging from one another or respectively turning to their mother countries. The Slovaks did not want to live in a country determined as Czech. Czechoslovakia was a fabrication of the policy of the allied Great Powers and would fall apart into its separate components without their constant protection – which is indeed what happened immediately after 1989. In the situation of 1939, support was sought from Germany. Vojtech Tuka, later Slovak Prime Minister, said to Hitler:

‘I lay the destiny of my people in your hands, my Führer; my people await their complete liberation by you.’233

The Slovaks wanted to be liberated, that is, to obtain their national independence; the Hungarians to be annexed to their mother country. Poland had already, without much ado, annexed the territories she claimed – among others the Olsa region already mentioned – without treaties nor negotiations. Czechoslovakia’s disintegration in 1938 was not unleashed through German intrigues, it was a consequence of dissent in the interior of that country.

In his brief accounts, Father describes the events and their consequences as follows:

‘In the course of the past months I had had various talks with the Foreign Minister Chvalkovsky and after an entirely new situation had arisen following the Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine and the declaration of independence of Slovakia, by the intermediary of our Chargé d’Affaires in Prague he now enquired of me whether the Führer would grant State President Hácha the opportunity of a personal interview. Adolf Hitler agreed and told me he wished to take the matter in hand himself. I had an exchange of cables with Prague in this sense and instructed our legation to stay out of it. It was replied to President Hácha that the Führer wished to receive him.

‘Up to this point, so far neither the Auswärtiges Amt nor I were aware of military preparations from our side. Shortly before the arrival of President Hácha I asked Hitler whether a state treaty should be prepared. He answered that he wanted “to go much further”.’234

Hácha’s visit to Berlin on 15 March ended with the well-known establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Father goes on to say:

‘The next day I travelled to Prague with Hitler, where, as he had charged me, I had to read a proclamation out loud that had been handed to me, wherein the states of Bohemia and Moravia were declared a Protectorate of the Reich.

‘Following upon this state ceremonial, I had a long, very serious discussion with Adolf Hitler at Prague’s Castle. I pointed out to him that the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia would have unavoidable considerable repercussions from the British and French sides. Since this discussion in Prague I have always stressed my conviction to him that further territorial changes would no longer be tolerated by England, whose armament and alliance policies were in every way intensified, without a war. Until the day war broke out my stance was opposed to the Führer’s opinion …

‘Adolf Hitler answered my objections, which concerned the possible reaction in England with the postulation that the Czech question was totally unimportant to England, whereas it was of vital importance to Germany …

‘At the time I said to the Führer that England would view the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia purely from the angle of the increase of Germany’s power … – but Adolf Hitler stuck to his opinion.’

These words, addressed openly to the head of government of the German Reich, once again struck a somewhat sour note with the ‘veteran fighters’. On 13 March 1939, Goebbels noted in his diary about these scenes:

‘Until three in the morning foreign policy debates at the Führer’s. Ribbentrop was also there. He advocates the point of view that it would unavoidably come to a conflict with England later. The Führer is preparing for this, but he does not consider it unavoidable. On this point Ribbentrop has no tactical flexibility. He is intransigent and therefore not quite in the right. However, the Führer will correct him.’235

In the light of these words, first of all what is to be corrected is the slander of Joachim von Ribbentrop disseminated by Weizsäcker and the other conspirators, in which it is stated that he had wrongly advised Hitler, telling him England was degenerate and would not fight.236 In England the truth could be known. On 4 May the British ambassador in Berlin, Henderson, wrote to Alexander Cadogan at the Foreign Office, who had replaced Vansittart:

‘certainly Ribbentrop did not give me the impression that he thought we were averse to war. Quite the contrary: he seemed to think we were seeking it.’237

Furthermore, Goebbels, the Foreign Minister’s enemy, accuses Ribbentrop of ‘intransigent’ behaviour toward Hitler, with no ‘flexibility’, as he puts it. In clear language this means that Father stood by his point of view although Hitler was evidently of a different opinion. In such a situation, there is no doubt Goebbels would have struck what was to his mind a ‘cleverer’ attitude. In government circles at the time he was considered the master of the art of gathering information, through middle-men, about Hitler’s thoughts and statements so that he could utter them as being his own, either directly to Hitler or in his presence, thus placing himself in a favourable light or to have a particular effect on Hitler. Father once recounted that Hitler had on occasion seen through this ploy and had told Father that he would henceforth refuse to tolerate the manner in which Goebbels, with the gentlemen of his entourage, ‘passed the ball’ so as to influence him.

Goebbels’ diaries disclose the constant controversies with Father over foreign propaganda, for the chief of propaganda erroneously thought he could consider this area as a specialized field for himself. In a dictatorship especially, press releases are naturally an exceptionally important instrument of foreign policy. Goebbels, as well as Hitler himself, however, often handled foreign propaganda on the basis of the experiences they had garnered from the domestic propaganda of the fighting days and gave too little consideration to the completely altered present circumstances under which the public abroad, which had to be addressed, was living.

Meanwhile, with the march into Prague Hitler seemed to have once again proved his political instinct. Father said:

‘The initial English reaction to what happened with Prague appeared at first to justify him [Hitler]; from the German standpoint it could be marked down as positive: on 15 March, in the House of Commons, Chamberlain stated, factually correctly, that no breach of the Munich Agreement had been constituted. The British government was no longer bound to their obligation vis à vis Czechoslovakia, since “the State whose frontiers we had proposed to guarantee [were] put an end to by internal disruption” …

‘In contrast, the English Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, however, from the start adopted a stance of rejection when notification of the Prague Agreement was given by the German ambassador von Dirksen.

‘Two days after his speech in the Commons, under the influence of the Opposition Chamberlain too abandoned his earlier tranquil attitude of “wait and see” and had completely modified his approach. This was clearly expressed in his well known Birmingham speech.’238

The British change of mind, which my father had expected as a consequence, was encouraged by American intervention. The journalists Drew Pearson and Robert S. Allen, who were close to Roosevelt, published an article in the Washington Times Herald on 14 April 1939, in which they confirmed that on 16 March of that year Roosevelt had requested of the British government, in the form of an ultimatum, that no concessions whatsoever should be made to the Reich and that they should pursue an anti-German policy.239 These reactions were not unforeseen. If my father expresses himself in the sense that following the Munich agreement he had repeatedly tried to maintain a friendly contact with the new government in Prague, then that is entirely plausible. In view of the German exertions to reach a fundamental agreement with Poland, any suspense or even a situation of ultimatum in Prague was clearly unwanted by him. If an arrangement with Poland were to be reached, then the Czech problem would anyway have lost its potentially explosive nature and a close collaboration would most probably have been achieved without spectacular steps being taken.

In view of the way things were, it was advisable to neutralize the Czech armed forces. There is no doubt that marching in with ‘drums and trumpets’ played into the hands of opponents’ propaganda. What mattered, however, was to wind up the action swiftly and without incident, which, with the agreement of the Czech government, was also achieved. Furthermore, already on the night of 14 March, British ambassador Henderson had, as instructed by Chamberlain, declared in the Auswärtiges Amt that the British government ‘have no desire to interfere unnecessarily in matters with which other Governments may be more directly concerned than this country’.240 This signalled official disinterest.

It is nowadays frequently presented in such a way that the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia had been the turning point in the politics of the West – of the British above all – in regard to Germany, and had triggered the rejection by Poland of the particularly favourable German proposals for the solution of the Corridor question, for one could no longer put any trust in German policy. It is overlooked – it must be said unfortunately often intentionally – that the German proposals had been put to the Polish government as early as November 1938. They had been offered by Hitler himself to the Polish Foreign Minister on the Obersalzberg and through the German Foreign Minister again to the Polish government in Warsaw, with Polish Foreign Minister Beck, as late as March 1939, also having been invited, via my father, to come to Berlin for negotiations on the issue. Beck, however ‘went to London’, as Father put it. Thereby Poland had gone over to the Western side and became a potential opponent. Neutralizing the well-equipped Czech forces became a compelling necessity.

It must therefore be borne in mind that the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the consequence of British and Polish policy directed against the Reich, and not the other way round. The very wide-ranging settlement offered to Poland by Germany would have substantially relieved the tension of the threat that the Czech army still undeniably constituted to the Reich. It must not be forgotten – I say it again – the Polish ambassador in Berlin, Lipski, had already in March 1939 confronted Father with a threat of war if the efforts on the part of Germany were pursued to unite Danzig with the Reich. Against this background it was evidently Hitler’s belief that for overriding aspects of foreign policy he would have to repudiate his own ethnic principles.

Father’s fears, that he expressed to Hitler, must also be taken against the background of his efforts to stir Hitler to accept a sounding out of the Soviet government so as to explore the possibilities of an agreement. Contrary to Hitler, Father assumed that Britain, and France with them, were now determined to obstruct any further strengthening of German influence in Eastern Europe. To his mind, it had to be attempted to keep Russia out of this grouping and to reach a positive policy towards the Soviet Union itself. It was a vital matter for Germany to keep her back protected, which meant to come to an arrangement with the Soviet Union. But Hitler hesitated; it was only on 10 May that the Reich’s relation with the Soviet Union was discussed in his presence.

Commercial relations with the Soviet Union had never been abrogated after 1933, but were overshadowed by the profound ideological antagonism between the two powers. The chief of the Auswärtiges Amt’s commercial policy department, Envoy Schnurre, at the time – that is, in January 1939 – as has been said, was conducting negotiations over a credit agreement of 200 million Reichsmarks. Father wanted Schnurre’s trip from Warsaw to Moscow to coincide with a meeting of Schnurre with Mikoyan, the Russian Minister of Foreign Trade; the journey was, however, cancelled then so as not to disturb the important negotiations with the Poles. It should also be mentioned that a vivid interest had been evinced on the part of Russia in the negotiations over the credit agreement, stressed by a démarche on the part of the then Russian ambassador Merekalov, who, as Schnurre writes, ‘came to the Auswärtiges Amt … and declared his government’s preparedness to conduct negotiations on this basis’.

Envoy Schnurre, who upon assignment by my father undertook the first steps in the task of exploring the possibilities of a fundamental new orientation of German foreign policy under the duress of the circumstances, has this to say on the subject:

‘The next startling step taken by the Russians was Stalin’s speech [the “Chestnut Speech”] pronounced on 10 March 1939 before the Party Congress XVIII. In it he accused the English, French and American press releases of intending to incite the Soviet Union against Germany and underscoring alleged German claims to the Ukraine. The speech concluded with the remark that the Soviet Union was not prepared to pull the chestnuts out of the fire for others, i.e. Western democracies. This declaration of Stalin’s signified that he was keeping the way open for a German-Soviet understanding.

‘Despite this, shortly after negotiations were opened with an English and a French delegation with the purpose of forming a common front of defence against a German aggression …

‘Commencing talks with England and France demonstrated that Stalin, as before, still had two irons in the fire …

‘The English-French efforts were further reinforced at the beginning of August 1939 by a military mission, working towards a military alliance. The English and French efforts were wrecked from the outset by the refusal of the governments involved to concede to the right of the Soviet Union to march through Poland and Romania in the event of a German attack. Despite all the efforts it was impossible to put aside the categorical refusal of the Polish and Romanian governments.

‘A further signal was the removal of the long-standing Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Litvinov, who retired on May 3rd 1939.

‘The Commissariat for Foreign Affairs was taken over by Molotov, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, who thus stepped more forcefully into the public limelight and became a central figure of German-Soviet politics.’241

I have already mentioned that an initial discussion took place on 10 May 1939 in Hitler’s presence, with the inclusion of two experts on Russia from the Auswärtiges Amt. The timing of the discussion is interesting insofar as it was only a few days after Litvinov’s departure. Until then Litvinov had been mentioned in the German press only under his double-barrelled name Litvinov-Finkelstein. He was Jewish, and was besides also an exponent of the anti-German policy of the Soviets, which he conducted under the postulation of ‘collective security’. This renewed signal may have triggered in Hitler a growing preparedness to occupy himself henceforth more intensively with the ‘Russian question’. Stalin had evidently intended the dismissal of the Jewish Foreign Minister as a further signal addressed to Germany.

Whatever the case, the visible haste with which the discussion with Hitler was now scheduled is noteworthy, for both the German ambassador in Moscow, Schulenburg, as well as the German military attaché there, General Ernst A. Köstring, were prevented from participating; Schulenburg was attending the wedding of the Persian Crown Prince in Teheran and Köstring was on a tour of duty in East Asia.

Would Hitler gradually become aware of the Reich’s perilous situation, that was to cause him to make a 180 degree turnabout of German policy? It did not as yet appear to be so, but reading in Schnurre, who after the war drew up a detailed account of developments in German-Russian relations from 1939 to 1941, there stands the following:

‘At the beginning of May Count von der Schulenburg [who was not present for the reason given above], Embassy Counsellor Hilger and I were invited to the Berghof to take part in a detailed discussion on the current situation of the Soviet Union … this led to the conference on Russia at the Berghof on 10 May 1939 as had been arranged.

‘Following corresponding preliminary talks with Ribbentrop, we arrived at the Berghof on 10 May 1939. We convened in the vast, spacious room of the Berghof, whose narrow end was fitted with a huge window giving a view over the alpine landscape. After a brief greeting by Hitler we sat down at the large round table. Besides Hitler and Ribbentrop, present were General Field Marshal Keitel, Chief of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces, Colonel General Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, as well as Walter Hewel, the liaison of the Foreign Minister to Hitler. Hewel belonged among Hitler’s comrades-at-arms of old. He had been imprisoned in Landsberg with Hitler, had worked in the domain of the economy of Indonesia for many years and was admirably distinguished by his openmindedness and amiability as a man of the world.

‘Although we were prepared for Hitler on this occasion to lead the discussion and expand into one of his usual lengthy monologues, it was not the case at all. Hitler let Hilger and myself brief him in every detail concerning the situation in the Soviet Union and the state of our relations.

‘He began the discussion with a question on the reasons for Litvinov’s dismissal. Hilger answered that Litvinov had been dismissed because he constantly insisted on reaching an understanding with England and France and he pursued the thought of a consensus for the disablement of Germany. Hitler’s next question as to whether under certain circumstances Stalin would be prepared to come to an understanding with Germany, gave rise to a detailed description of the various efforts on Russia’s part to reach an understanding with Germany. We particularly noted Stalin’s speech of 10 March and it was somewhat surprising that none of the participants was familiar with the wording of the speech, although the embassy as well as the Auswärtiges Amt had reported on it in detail.

‘The discussion subsequently turned to the Red Army, that had on the one hand been weakened by the purges of 1937/1938 but on the other had become a power to be reckoned with through reorganization and a steely discipline. Stalin was striving to restore the strength of Russian national consciousness. The great personalities of the tsarist past were strongly brought to the fore in literature and the theatre, such as for instance Kutuzov as the victorious opponent of Napoleon, Peter the Great, and others. In economic matters we pointed out the major possibilities that the Soviet Union’s wealth in raw materials could offer us and the close contacts which had already been made.

‘Hitler listened attentively to our remarks, interrupting nobody. He asked more questions, so as to extend the discussion, without revealing his own stance toward the issue of an understanding of ours with the Soviet Union. We thought he would tell us how the talks with the Russians should proceed but were disappointed in this expectation. He thanked us – and the meeting was over.’242

Schnurre’s statement that none of the participants was familiar with the wording of Stalin’s speech (the ‘Chestnut Speech’) is of course not true, for it was precisely this signal transmitted by Stalin in the speech that Father had employed so as to persuade Hitler to rethink Germany’s Russian policy. How else would it have come to a discussion with Schnurre and Hilger? It is, however, a well-known routine for leading figures to let collaborators make statements once again of facts already known, for interesting shades of meaning may be distinguished from the gist of the presentation, not only in view of what is actually happening but also as to the stance of the speaker to the problem at hand, which in each case has to be taken into consideration when assessing the presentation. Schnurre will probably have meant the military men, who quite probably, as was Hitler’s wont, had not been comprehensively informed.

Hitler’s overt distancing from the Soviet Union since 1933 does not seem comprehensible, for a power such as the Soviet Union then represented could not be ignored as if it did not exist. It is slightly reminiscent of the fatal instructions given by Hitler at the beginning of the war with Russia, denying the Auswärtiges Amt any competence in the sector of Soviet Russia, as if this international power no longer existed.

When following Schnurre’s account it may be seen that the meeting on 10 May 1939 on the Obersalzberg had been a matter of a purely informative discussion. I assume it was as a result of Father’s insistence on again using Litvinov’s dismissal as motivation that had brought Hitler once more to discuss the ‘Russian question’. From Hitler’s point of view, playing the meeting down, and the absence of the ambassador and the military attaché, could also have been intended to cloak his intentions. It was evidently still difficult for him to reach a decision about an understanding with the Soviet Union, although the encirclement of the Reich, in view of the negotiations of the Anglo-French delegations in Moscow, seemed possibly to be close to a conclusion.

However, even regardless of the hostility of the USSR, the situation in which Germany found herself in the spring of 1939 was extremely grave. This is why following the conclusion of the pact with the Soviet Union, Father spoke of a great relief of tension in the foreign policy sector. Whereas nowadays German historians think they can detect the first signs and prerequisites for Hitler’s alleged plans for world domination, this is not comprehensible, in view of the facts. Basically, Hitler still hoped for an agreement with Poland, thereby for an arrangement with Britain. This was in the end what was also accomplished by the pact of non-aggression with the USSR. He could not know what powers had wrought influence on the decisions made by the British and French governments, in order to prevent such an arrangement on the basis of the German offer to Poland; an arrangement that in Hitler’s opinion could only be in the interests of Poland.

For six years he had directed his foreign policy with the objective of a limitation of the Soviet Union, for which he had sought a partnership with both Western European powers, and now he was supposed to have bonds with ‘these people’ – the Soviets? For a pragmatist such as Father that presented no fundamental problem, but for Hitler the road to Moscow signified a rough path to tread. One may nonetheless also comprehend Hitler’s wavering out of factual causes, quite irrespective of his basically anti-Bolshevik policy so far. It was perfectly reasonable to think that Stalin was making these advances to the Reich solely to present himself to the Western powers in the light of a more valuable player, thus demonstrating that he had other irons in the fire. It may perhaps be possible one day to deduce from Russian documents – insofar as they will not, nor have been, manipulated – what Stalin’s true thoughts were when he introduced a rapprochement with the Reich. There is today a widespread theory that Stalin’s final decision to take up the option of Germany had been triggered by the strict refusal of the Polish and Romanian governments to condone the right of Russian troops to march through their national territory in case of war (casus foederis). To my mind this explanation does not extend far enough. At the back of Stalin’s policy the hope must have existed to see the Central European and Western power blocs embroiled in a conflict, as Litvinov had allegedly said to Goldmann. The weight and position of the Soviet Union could only be reinforced in such an eventuality, since all options would be open to it.

The Polish and Romanian governments were doubtless right to start from the premise that once they were there they would be unable ever again to be rid of Russian troops who would come to their ‘assistance’. The Polish and Romanian governments quite rightly saw no chance of the two Western powers protecting them from the Russians once these were in the country, a perception that was to become a bloody reality five years later. Such thoughts must have nourished Hitler’s hopes of at last coming to an agreement with Poland and Britain in the Danzig and Corridor question, for unlike Stalin he did not think of demanding the right to march through.

Schnurre reports that at Pentecost 1939 a session with Father took place at our farmhouse near Bad Freienwalde for consultation as to further proceedings vis à vis the Soviet Union. Participants were State Secretary Weizsäcker, the lawyer and expert in international law Ambassador Gaus, Undersecretary of State Woermann and Schnurre himself.

They had judged the chances of an understanding with Russia with pessimism and conceded that endeavours toward England and France had better prospects. This opinion, expressed by Weizsäcker, is not surprising since behind the back of the German government he had warned Britain against a German-Russian understanding. Schnurre will have pressed for reinforced resumption of politico-commercial efforts, which seems perfectly plausible. Since this is also what was decided, Father’s wish to continue the talks is obvious.

It was already somewhat awkward to put the discussion with the Soviets in train at all without mutual loss of face after one had for years ‘covered’ each other ‘with pails of manure’, as Stalin later expressed it to Father in Moscow. It was no less difficult for Father to convince Hitler, who had followed the banner of anti-Communism, of the necessity of a rapprochement with the Soviet Union. Father says of this:

‘To seek a settlement with Russia was originally purely my very inherent243 idea; I had represented it to the Führer because I wanted on the one hand to bring relief to German foreign policy, in view of the attitude of the West, and on the other, however, also to ensure Russian neutrality for Germany in the event of a German-Polish conflict.

‘In March 1939 I thought I read into a speech of Stalin’s a wish of his for improvement of the Soviet-German relations. He had said then that Russia did not intend to “pull the chestnuts out of the fire” for certain capitalist powers.

‘I showed the Führer the text of Stalin’s speech and urged for authorization to take the necessary steps so as to ascertain whether a genuine wish on Stalin’s part was in fact behind this speech. At first Adolf Hitler’s response was temporizing and reluctant.’244

Even on 29 June 1939, following a recording and presentation of the above-mentioned by Legation Councillor Hewel, Hitler made public that the German government was ‘not interested in a resumption of the economic discussions with Russia at present’.245 There was still a lot of persuasion to be done on Hitler in the sense of a German-Russian understanding. Father, however, was not discouraged and charged Schnurre with the task of undertaking a more greatly in depth sounding-out of Russian intent from the current negotiations over the credit treaty, as the latter reported:246

‘At the end of July, Hitler decided to take the initiative vis à vis the Soviet Union.247 On 26 July 1939 I received from Ribbentrop instructions to invite the Chargé d’Affaires of the Soviet Union’s diplomatic mission Astakhov, and the Head of the Trade Delegation Babarin to dinner, and to conduct a wide-ranging political discussion. This discussion took place on 26 July 1939. I had asked them to Ewest, the old wine restaurant in the centre of Berlin … The Russians took up the conversation about the political and economic problems of interest to us in a very lively and interested manner so that an informal and thorough discussion of the various topics mentioned to me by the Reich Foreign Minister was possible.’

Schnurre then sketched out three stages in which the German-Soviet collaboration could be realized, on the premise that ‘the Soviet Government attached importance to it’. In his opinion, ‘controversial problems of foreign policy, which would exclude … an arrangement between the two countries, did not … exist anywhere along the line from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.’

Schnurre then went on to describe Astakhov’s reaction:

‘With the warm approval of Babarin, Astakhov designated the way of rapprochement with Germany as the one that corresponded to the vital interests of the two countries. However, he emphasized that the tempo might well be only slow and gradual.’248

Here the time factor comes once more to the fore, a card cleverly played by the Russians and uncomfortable for the German side, for time was pressing. Through Astakhov, Molotov let Schnurre know that confirmation of the discussion was however awaited from an authorized German source. Thereupon the German ambassador, Schulenberg, was instructed to have a corresponding discussion with Molotov. The sounding-out resulted in the ascertainment of an evinced Russian interest, but Molotov designated the conclusion of a merchandise and credit agreement as an essential prerequisite and the touchstone for undertaking political talks. The Russians bid the full value of their trump card, that contrary to the German side they did not have any time problems, and let the Germans know this.

On 2 August Father himself had a discussion with Astakhov, the Russian chargé d’affaires. He briefed Count von Schulenburg in Moscow in a cabled decree that is reproduced here verbatim because of the importance of the discussion:249

‘Last night I received the Russian Chargé d’Affaires, who had previously called at the Ministry on other matters. I intended to continue with him the conversations with which you are familiar and which had been previously conducted with Astakhov by members of the Foreign Ministry with my permission. I started with the trade treaty discussions which are at present progressing satisfactorily, and described such a trade agreement as a good step on the way toward the normalization of German-Russian relations, if this were desired. It was well known that the tone of our press with regard to Russia had for more than six months been substantially different. I considered that, insofar as the Russians so desired, a remoulding of our relations would be possible on two conditions:

a)Non-interference in the internal affairs of the other State (M. Astakhov believes that he can promise this forthwith).

b)Abandonment of a policy directed against our vital interests. To this Astakhov was unable to give an entirely clear-cut answer, but he thought his Government had the desire to pursue a policy of understanding with Germany.

‘I continued that our policy was an unswerving and long-range one; we were in no hurry. We were favourably disposed towards Moscow; it was, therefore, a question of what direction the rulers there wished to take. If Moscow took a negative attitude, we should know where we stood and how to act. If the reverse were the case, there was no problem from the Baltic to the Black Sea that could not be solved between the two of us. I said that there was room for the two of us on the Baltic and that Russian interests by no means needed to clash with ours there. As far as Poland was concerned, we were watching further developments attentively and ice cold. In case of Polish provocation we would settle accounts with Poland in the space of a week. For this contingency, I dropped a gentle hint at our coming to an understanding with Russia on the fate of Poland. I described German-Japanese relations as good and friendly; these relations were lasting ones. As to Russian-Japanese relations, however, I had my own special ideas (by which I meant a long-term modus vivendi between the two countries).

‘I conducted the whole discussion in a tone of composure and in conclusion again made it clear to the Chargé d’Affaires that in high policy we pursued no such tactics as did the democratic Powers. We were accustomed to building on solid ground, did not need to pay heed to vacillating public opinion, and did not desire any sensations. If conversations such as ours were not handled with the discretion they deserved, they would have to be discontinued. We were making no fuss about it; the choice lay, as had been said, with Moscow. If they were interested there in our ideas, then M. Molotov could, when convenient, pick up the threads again with Count Schulenburg.

‘Addition for Count Schulenburg:

‘I conducted the conversation without showing any haste. The Chargé d’Affaires, who seemed interested, tried several times to pin the conversation down to more concrete terms, whereupon I gave him to understand that I would be prepared to make it more concrete as soon as the Soviet Government officially communicated their fundamental desire for remoulding our relations. Should Astakhov be instructed in this sense, we for our part should be interested in coming to more concrete terms at an early date. This exclusively for your personal information.’

It is easy to see that there was great interest on the part of Germany in a speedy progress in the negotiations. However, Father wished to cloak this interest as much as possible and expressly stated that there was no hurry and that no sensationalisms were desired. Hitler had long vacillated to abandon his anti-Russian policy. Now he was gradually coming under pressure by the passage of time.

Hitler was not a skilled negotiator. He did not have the patience for a long-drawn-out negotiation that would elicit the opponent to take a stand and to let discussions reach the decisive point of maturity, with all the necessary finesse. This is why at the hotel on the Petersberg mountain Father’s intervention in the negotiations during the Sudeten crisis had had to save the situation when news of the Czech mobilization had exploded into the discussion, and which but for a hair’s breadth would have caused Hitler to break off the negotiations. On this, Father writes:

‘In order to judge Hitler’s personality, there is another aspect of importance: he was hot-tempered and could not always control himself. This was sometimes also apparent in diplomatic occasions. He had been about to break off the conference with Chamberlain in Godesberg, when the news of the Czech mobilization came and he spontaneously jumped up, red in the face, a sure sign. I intervened to calm him down and Hitler later thanked me for having thereby rescued the conference.’250

It is incidentally further proof that Hitler clearly did not want to precipitate a showdown in the Sudeten crisis. This trait of Hitler’s personality was to have a fateful effect on German policy when in 1940 Molotov’s wishes to exert a wide-ranging influence in Europe irritated him to such an extent that he cut short any further negotiations with the Russian government.

The wire addressed to Schulenberg discloses that despite the externally apparent equanimity reigning in the German side, it was vital to come to an understanding with the Soviet government as soon as possible before a situation of ultimatum were to arise in relations with Poland. On the German side it was calculated, with some justification, that an understanding between Germany and Russia would induce Poland to back down. In any case there were two options opened by an understanding with Russia: either a peaceful solution, which according to the German estimate had a good chance of succeeding if there were an agreement with Russia, or the last resort: military action, in other words.

Father’s words, that nowadays sound rather grandiose, about German policy being ‘unswerving’ and built on ‘solid ground’, in contrast to the ‘tactics’ of the Western democracies, absolutely make sense in the context. It was a matter of making it clear to the Russian government that it was a case of a fundamental turn-about in German foreign policy and not a mere tactical dodge with a short-term expiration date, with the objective to pressurize Poland to back down in the Danzig issue or to induce the Western powers to influence Poland in that sense. Father’s formulations are justified when seen in this light. Since Hitler had come to power, German policy had been geared to come to an arrangement with Britain, by eschewing any ‘see-saw’ policy between East and West. In the more than six years that Hitler had determined German foreign policy he had remained consistently anti-Bolshevik, and had never been tempted to flirt with the Soviet Union for tactical reasons by resuming what had been designated as a ‘Rapallo policy’ since 1922. It was therefore already absolutely of significance for the Russian side if the German Foreign Minister spoke of an ‘historic turning-point’ arrived at in German policy. Mutual mistrust was naturally not to be dissipated overnight. Neither side wished to ‘play the joker’, as we say, for the other side, but Father could in all confidence point to a consistent German policy.

If nowadays – I wish unhesitatingly to call it a cliché – it is maintained, with no further reflection, that the alliance with Russia now placed Hitler in the position of at last being able to wage ‘his war’, it simply does not correspond to the facts, for on the contrary there was hope in Berlin that the conclusion of a German-Russian treaty would have brought about a diplomatic constellation who could be seen as the requisite for a peaceful settlement of the Danzig-Corridor problem. There were others who backed a war in this situation. Just at the beginning of August, the Polish government had again openly threatened to take up arms if the government of the German Reich further pursued the Danzig problem.251

The Russians had declared that the conclusion of the merchandise and credit agreement, under negotiation since the spring, was a pre-condition for political discussions. Schnurre received instructions from Father to speed up the negotiations as much as possible. Delays cropped up every so often, as Babarin had to obtain the approval of Moscow for every detail. According to Schnurre, Father asked him ‘not to come to grief over a trifle’; it was urgent to conclude, so as to enable the opening of the ‘political talks’. On the German side there was no option left but to exert pressure. In a cable to Schulenburg of 14 August, Father said approximately the following: differing philosophies would not prohibit ‘a reasonable relationship between the two States, and the restoration of new, friendly cooperation’. There existed no ‘real conflicts of interests between Germany and Russia’: there would be no question ‘between the Baltic and the Black Sea which cannot be settled to the complete satisfaction of both countries’. The German-Russian policy had come ‘to an historic turning-point’. The ‘natural sympathy of the Germans for the Russians’ had never disappeared. ‘The policy of both States’ could be ‘built … on that basis’. That was an optimistic prognosis, but sincerely meant by Father. Later, in the winter of 1940/41, he tried everything to dissuade Hitler from his decision to attack Russia, and after the outbreak of the German-Russian war he pressed Hitler again and again or an authorization to extend feelers for peace in the direction of the Soviet Union. The decisive paragraph then read as follows:

‘As we have been informed, the Soviet Government also feel the desire for a clarification of German-Russian relations. Since, however, according to previous experience this clarification can be achieved only slowly through the usual diplomatic channels, Foreign Minister Ribbentrop is prepared to make a short visit to Moscow in order, in the name of the Führer, to set forth the Führer’s views to M. Stalin. In his, Herr von Ribbentrop’s, view, only through such a direct discussion can a change be brought about, and it should not be impossible thereby to lay the foundations for a final settlement of German-Russian relations.

‘Annex: I request that you do not give M. Molotov these instructions in writing, but that you read them to him verbatim. I consider it important that they reach M. Stalin in as exact a form as possible and I authorize you, if occasion arises, to request from M. Molotov on my behalf an audience with M. Stalin, so that you may be able to make this important communication directly to him also. In addition to a conference with Molotov, a detailed discussion with Stalin would be a condition for my making the trip.’252

The Russians played a game of gaining time so that in the end Hitler personally telegraphed Stalin to obtain for the German Foreign Minister an early date for a visit to Moscow. In Hitler’s telegram the pressure that time was gradually exerting on Berlin is shown, because of the Polish threats of war and the automatic effects from their alliance with the Western powers if the Danzig-Corridor problem was still to be solved by 1939 ‘in one way or another’ in the German sense.

In his telegram to Stalin, Hitler expressed his satisfaction at the conclusion of the commercial agreement and accepted the draft of a non-aggression pact handed to Schulenburg by Molotov, but considered ‘it urgently necessary’ to clarify the questions connected with it as soon as possible. Hitler wired:

‘The substance of the supplementary protocol desired by the Government of the Soviet Union can, I am convinced, be clarified in the shortest possible time if a responsible German statesman can come to Moscow himself to negotiate … In my opinion, it is desirable, in view of the intentions of the two States to enter into a new relationship to each other, not to lose any time. Consequently, I therefore again propose that you receive my Foreign Minister on Tuesday, August 22, but at the latest on Wednesday, August 23. The Reich Foreign Minister has the fullest powers to draw up and sign the non-aggression pact as well as the protocol. A longer stay by the Reich Foreign Minister in Moscow than one to two days at most is impossible in view of the international situation. I should be glad to receive your early answer.’253

Father added as instruction to Schulenburg: ‘Please hand to M. Molotov the above telegram of the Führer to Stalin in writing, on a sheet of paper without letterhead.’ Finally, on the next day, that is 21 August 1939, Father sent Schulenburg a further telegram in which the urgency of the German wish for negotiations was underlined: ‘Please do your utmost to ensure that the journey materializes. Date as in telegram.’

At 3.00 pm on 21 August Schulenburg handed Hitler’s message addressed to Stalin to the People’s Commissar for foreign affairs, Molotov, and subsequently telegraphed Berlin that Molotov had evidently been ‘deeply impressed’. Schulenburg was asked to see Molotov again as early as 5.00 pm, when Stalin’s answer to Hitler was given to him. It states:

‘I thank you for the letter.

‘I hope that the German-Soviet non-aggression pact will bring about a decided turn for the better in the political relations between our countries.

‘The peoples of our countries need peaceful relations with each other. The assent of the German Government to the conclusion of a nonaggression pact provides the foundation for eliminating the political tension and for the establishment of peace and collaboration between our countries.

‘The Soviet Government have instructed me to inform you that they agree to Herr von Ribbentrop’s arriving in Moscow on August 23.’254

Father considered the non-aggression pact foreseen to be concluded with the Soviet Union as of such significance that, without regard for his personal self, he wanted its conclusion in no way to be jeopardized. He wrote on the subject:

‘I had initially suggested that not I but another plenipotentiary – I had Göring in mind – should be sent to Moscow. Because of my activity as ambassador in England, my Japanese connections and my entire foreign policy so far I thought I was all too firmly established as anti-Communist for a mission to Moscow. But the Führer insisted on my being sent because he thought that I “understood it better”.’255

Father had two goals in sight when he constantly urged Hitler to speedy and broad-based discussions with Russia. For Father the most important aspect was breaking the encirclement of the Reich. Beyond this it did, however, not seem to be a mistake to assume that if there were a successful agreement reached with the Russians the prerequisites were there for the Danzig-Corridor problem to be solved by peaceful means. The German side could reasonably expect that under the impact of a German-Russian collaboration Poland would accept the proposals, of further benefit, from the German government.

For one reason or another, the labour service camp in which I served in August 1939 had been given a long weekend’s leave, so I took the opportunity to visit my parents in Fuschl,256 where they were staying when Hitler was on the Obersalzberg. As soon as I arrived, Mother took me aside and briefed me as to how things stood. Father was to fly to Moscow to try to conclude a pact of non-aggression with the Russians. I was most profoundly impressed and – this is not in retrospect – extraordinarily relieved. Since for years I had been able to follow the unavailing German efforts for the realization of the ‘Western option’ at first hand, I could see the peril of a renewed encirclement of the Reich, that in 1914 had had such a fateful impact, looming clearly once again. It was going to be countered by Father’s journey.

Once again Mother recounted the diverse phases of the developments that had now finally led to Father’s mission to Moscow. There was of course no certainty that his visit would have a successful outcome. In this sense the instruction to Schulenburg is without any doubt also to be understood, namely that Hitler’s telegram should be delivered to Molotov on paper ‘without letterhead’.

Father’s notes confirm the uncertainty with which he anticipated his journey:257

‘It was with mixed feelings that I stepped on the soil of Moscow for the first time. We had stood against the Soviet Union with hostility for many years and had given battle ideologically to the utmost … Above all, for us Stalin was a kind of mystic personality.

‘I was aware of my particular responsibility in this mission, since it was I myself who had proposed an attempt for an understanding with Stalin to the Führer … At the same time the English and French military missions were still negotiating in Moscow with the Kremlin over the projected military pact … We arrived at Moscow airport in the Führer’s aeroplane on 23 August in the afternoon between 4 and 5 o’clock where the flags of the Soviet Union and the Reich blew next to one another. We were received by our ambassador Count von der Schulenburg and the Russian ambassador Potemkin. Following the march past of a guard of honour of the Soviet airforce, which undoubtedly made a good impression as to appearance and military bearing, accompanied by a Russian colonel we went to the former Austrian embassy, where I was to stay for the duration of my visit.

… and received there the information that I was expected at the Kremlin at 6 pm. Who would be negotiating with me, Molotov or Stalin himself, was not to be elicited. “Odd Muscovite customs” I thought to myself. Shortly before the appointed time we were fetched once again by the broad-shouldered Russian colonel – I heard he was in command of Stalin’s bodyguard – and soon drove into the Kremlin … then we stopped at a small portal and were taken up a short flight of tower steps. At the top we were led by an official into a long study at the end of which Stalin stood awaiting us, with Molotov next to him. Count Schulenburg could not repress an exclamation of surprise. Although he had been serving as ambassador in Moscow for several years now, he had never spoken to Stalin himself!’258

It must be mentioned at this point that at the time Stalin did not occupy a fixed position of state, but was simply General Secretary of the Party. One can imagine his personality and the authority he must have emanated to have ruled that gigantic country, as was the case, so absolutely from an indirect position. Only shortly before the German-Russian war did Stalin undertake the offices of head of state and Generalissimus of the Soviet Union.

Father carries on:

‘After a brief formal greeting, the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and I. There were present besides our interpreter, Embassy Counsellor Hilger who was an excellent connoisseur of Russian relations and the young blond Russian interpreter Pavlov who apparently had Stalin’s special confidence.

‘At the outset of the discussion I expressed Germany’s wish to place the German-Soviet relationship on a fresh footing and to bring about an equalization of interests in all sectors; we desired an understanding as far-seeing as possible with Russia. I thereby referred to Stalin’s speech in the spring wherein in our opinion he had expressed similar thoughts. Stalin turned to Molotov and asked him whether he wished to answer first. Molotov however asked Stalin to take over since he alone was competent to do so.

‘Stalin then spoke – briefly and succinctly, without too many words, but what he said was clear and unmistakeable and, it seemed to me, demonstrated the same wish for a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin utilized the distinctive expression: we may have “covered” each other “with pails of manure” for many years, but that was no reason not to be able to get on well together again. He had made his speech in the spring fully consciously so as to indicate his willingness for an understanding with Germany. We for our part had apparently understood this correctly. Stalin’s answer was so positive that after the first basic utterances in which the preparedness of both sides to conclude a pact of non-aggression had been established, it was possible immediately to go into the issues of the material side of the demarcation of mutual interests and the German-Polish crisis in particular. There was a favourable atmosphere at the negotiations although the Russians are known to be tough diplomats. The spheres of influence in the countries interjacent to Germany and the Soviet Union were demarcated. Finland, the greater portion of the Baltic States and Bessarabia were declared as belonging within the Soviet sphere. In case of the outbreak of a German-Polish conflict, which in the current state of affairs could not be excluded, a “line of demarcation” was agreed.

‘Stalin had declared already in the course of the first part of the negotiations that he wished to have certain spheres of influence. As is known, by “sphere of influence” it is understood that the interested state conducts negotiations that concern the said state only, with the governments of the countries belonging to its sphere of influence, while the other state explicitly [shows itself to be] disinterested.

‘As to this, Stalin assured me he did not want to touch the domestic structure of these states. I had replied to Stalin’s claim for spheres of influence by pointing to Poland: the Poles were becoming ever more aggressive and it would be desirable, in case they brought matters to a war, to fix a line so that the German and Russian interests would not clash. This line of demarcation would be along the courses of the rivers Vistula, San and Bug. I indicated to Stalin on this point that on the part of Germany every effort would be made to solve the issues in a diplomatic-peaceful form.

‘It is self-evident that agreements touching upon other countries are not committed to treaties destined to be made public and that instead secret contracts are concluded for this purpose. There was a further reason for the agreement to be secretly contracted: the German-Russian agreement contravened an agreement between Russia and Poland and the treaty concluded in 1936 between France and Russia foreseeing a consultative procedure in the case of treaties with other countries.

‘The relentlessness of Soviet diplomacy showed in the issue of the Baltic and especially in regard to the port of Libau which the Russians laid claim to for their sphere of influence. Although I had plenipotentiary powers for conclusion of a treaty, in view of the import of the Russian claims I thought it right to consult Adolf Hitler. The negotiations were therefore interrupted and resumed at 10 pm when I had Hitler’s agreement.’

a)The annexation and division of the Polish state territory after the end of the German-Polish and respectively Polish-Soviet military action. (Capitulation of the last Polish field troops on 6 October 1939.)

b)German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty dating to 28 September 1939: Map bearing the signatures of Stalin and Ribbentrop.]

It must be said here that it is a well-known trick of negotiations to play up the weight of concessions one is prepared to make under certain circumstances, by means of appearing to delegate the decision thereon back to a higher level. This is what Father resorted to here when he referred the decision whether to relinquish the port of Libau to the Russians back to Hitler. Father continues:

‘There being no more difficulties, the pact of non-aggression and the secret supplementary protocol were initialled and signed already before midnight. A light and simple dinner was then served to the four of us in the same room, which was Molotov’s study. Right at the beginning there was a surprise: Stalin stood up to say a few words, in which he spoke of Adolf Hitler as the man whom he had always extraordinarily revered. In strong terms of friendship, Stalin expressed the hope that a new phase in German-Soviet relations had been introduced by the treaties just concluded. Molotov also stood up and expressed himself similarly. I replied to our Russian hosts with an address in equally amicable words. In this way, but a few hours after my arrival in Moscow an understanding had been established such as I had thought unthinkable when I had departed from Berlin and that moreover fanned my greatest hopes for the future evolution of German-Soviet relations.

‘From the first moment of our meeting, Stalin had made a profound impression on me – he was a man of unusual stature. His sober, almost dry and yet so apt manner of speaking and the hardness as well as however his generosity in negotiation showed that he rightly bore his name [trans., Stalin = ‘Man of Steel’]. The content of my talks and conversations with Stalin gave me a clear understanding of the strength and power of this man who had but to nod for it to be a command obeyed as far as the most distant village of Russia’s enormous vastnesses and who had succeeded in blending together the two hundred million people of his nation more strongly than any Tsar before had been capable of. A minor indicative occurrence that came about at the end of this evening seems to me worth mentioning: I asked Stalin whether the Führer’s photographer accompanying me could take a few pictures. Stalin agreed and it was probably the first time he permitted this to a foreigner in the Kremlin. When however among other shots Stalin and we the guests were photographed with glasses of the Crimean sparkling wine we had been offered, Stalin did not allow it – he did not want it made public. As I asked, the photographer removed the film from the camera and handed it over to Stalin; he gave the little roll back however, remarking that he trusted that the picture would not be published. Trivial as the episode may have been, it was nevertheless illuminating of the generous attitude of our hosts and of the atmosphere in which my first visit to Moscow was concluded.’

The annexation and partitioning of Polish national territory after the end of German-Polish and Polish-Soviet conflicts. [The last Polish field troops on 6 October 1939].

German–Soviet Frontier Treaty from 28 September 1939: Map with the signatures of Stalin and Ribbentrop.

On the conclusion of the treaty, Father writes:

‘Rescinding Bismarck’s Russian policy had introduced the encirclement of Germany that led to the First World War. In the situation the year 1939 was in, resuming the historical relations for realistic reasons signified a political security factor of the first order.

‘For me personally, who had proposed this settlement with Russia to the Führer, in detail my hopes were raised for:

1)Gradual elimination of one of the most dangerous causes for dispute that could threaten the peace in Europe by a foreign policy bridging the oppositions in the world views between National Socialism and Bolshevism;

2)Establishment of a truly amicable German-Russian relationship as one of the foundations of German foreign policy in Bismarck’s sense;

3)For the particular state of affairs as they stood in August 1939: the possibility of a diplomatic solution to the Danzig-Corridor problem in the sense of Hitler’s proposals.

‘On 24 August I flew back to Germany with our delegation. It was foreseen I was to go by air from Moscow to Berchtesgaden so as to report to Adolf Hitler at the Berghof. I was thinking about proposing to him that a European conference should be held for pacification of the Polish question.

‘Surprisingly, by radio message our aeroplane was re-routed to Berlin where Hitler had flown the same day. For security reasons our machine had to make a wide detour over the Baltic.’259

Father speaks of a ‘security factor of the first order’; the relief may almost be sensed that as a first step, due to the Moscow treaty the build-up of the ring of encirclement around the Reich had been broken. By the conclusion of the German-Russian treaty, world political-power relations had once again been fundamentally altered. For Germany the European equilibrium had been restored in a positive sense. Henceforth the Reich entertained friendly relations with Russia, Japan, Italy and Spain, as well as several smaller states in Eastern and South-eastern Europe. The strangulating encirclement of the Reich that was beginning to show had been prevented.

Furthermore, it had been succeeded in manoeuvring Poland, who had played the card of the West, into a situation whereby actually only a friendly settlement with Germany remained as a possibility, so as not to bring about the fateful situation that in 1935 Beck had set out so strikingly before Laval. It was Piłsudski’s insight that Beck had transmitted to Laval. For Piłsudski too lost sleep over the cauchemar des coalitions (nightmare of coalitions) and he had tried to soften the nightmare through a wise policy – his successors evidently slept better. It will be seen what sort of ‘comfortable pillow’ it was on which the Polish politicians thought to endure their country’s perilous situation.

However, from the German side it had to be assumed that Poland was now ready to negotiate under the present completely altered circumstances. A glance at the map in fact makes it clear even for military laymen that ‘no power in the world’ (as Beck had expressed it to Laval) could give Poland, wedged in between Germany and Russia, the requisite support if a military confrontation was indeed ventured.

It could of course now become rather more ‘costly’! As has been seen, Hitler would have gone to considerable expense to ensure Poland’s entry into the Continental-European-anti-Soviet bloc. It had been in no way a matter of ‘so to speak’ that Father had declared to Beck as well as Lipski that nobody but Hitler could guarantee the Corridor borders.260 At present too, despite the pact of nonaggression with Stalin, it was not demanded of Poland to give up parts of her state territory. However, now, in the negotiations of the last week of August 1939, Hitler did demand a national referendum in the Corridor under international supervision, on the basis of the 1920 population structure. It can hardly be claimed that it was an unreasonable demand, and the British ambassador Henderson was also of the same opinion. I have already pointed out that after the First World War Poland had demanded that the populations of the regions ceded to Poland should opt for Poland if they did not want to be expelled. This referendum Hitler now demanded only for a restricted part of the Corridor.

Poland therefore remained the way out for the negotiations. Basically, Hitler had no antipathy toward Poland. A remark of his has been quoted: ‘Every Polish division at the Russian border spares me a German one!’ Although the comparison can certainly not be qualitatively interpreted, it does make sense, if countered by the fact that a Poland hostile towards the Reich would necessitate a substantial military expense to secure the unfortunate borders of the Reich against Poland. Even if Poland’s tendency to overestimate her own potential is assumed and taken into account, and that the Poles had taken the propaganda slogans ‘the German tanks are made of cardboard’ at face value – which would not be speaking for the qualification of the Polish General Staff – it would after all have been realized in Warsaw that they had no chance against an active German-Russian alliance.

It shows clearly from what has been said before how hard it had been for Hitler to accomplish a ‘turn-about’ – as proposed by Father – of German foreign policy from the anti-Soviet Central European bloc with the integration of Poland to a pro-Russian and thereby anti-Polish policy. As a matter of fact he had vacillated much too long. Hitler and my father – it cannot be said too emphatically – had accomplished this turn under duress, since, influenced by the British and the Americans, Poland had rejected them and had opted for the anti-German side. And yet Poland could still have reached a solution that did not place either their national substance nor honour in question.

It should not be forgotten that until a few days before the German-Russian pact it had still been unclear to the German side whether the Russians would decide on an alliance with the Reich or with the Western allies. Hitler’s hesitation, next to his inhibitions, to come to an arrangement with the Bolsheviks is to be explained only by reason of his hopes that he could after all settle with Poland, and in the broader sense also with England, thereby avoiding both the war and ideological compromise by an agreement with the USSR.

His diplomatic démarches, just before the outbreak of war, are also proof that it was important to him not to let things reach the point of a military confrontation. Other than the official channels, he also utilized unofficial ways, such as for instance calling in the Swede Birger Dahlerus. Decisive is, however, the abrogation on the afternoon of 25 August of the order to advance, on Father’s instigation, after the ratification of the new British-Polish treaty was made known, which gave more precision to the mutual guarantee offered by both countries in March: that is limiting it to a conflict with Germany.261 If Hitler had only been concerned with the Russian cover of the rear to ‘pick a quarrel so as to have his war’, there would have been no cause to rescind the marching order for the Wehrmacht on 25 August at the last possible moment and under considerable technical difficulties. The countermand definitely harboured great military, and above all political, risks.