4

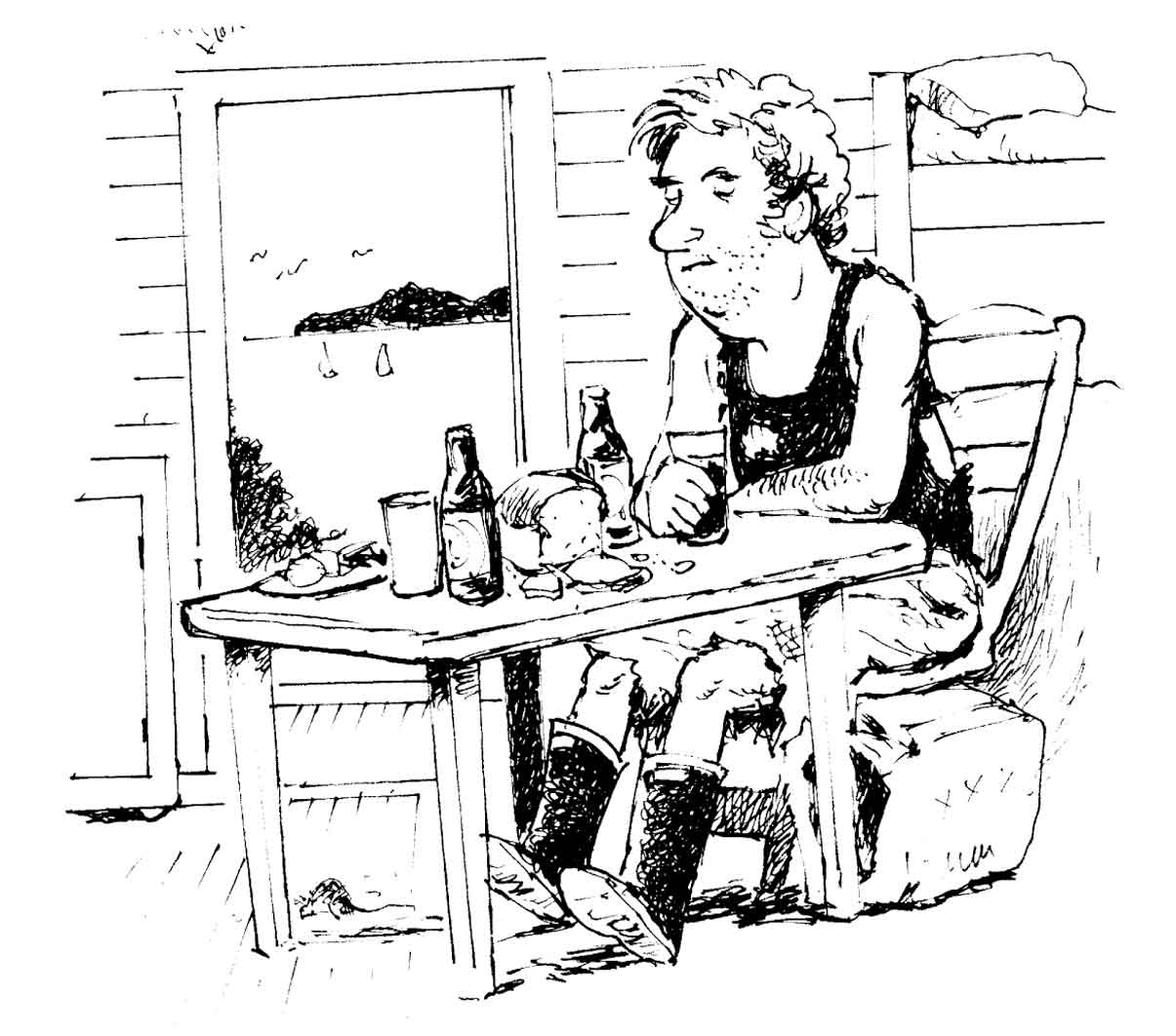

Après weed spraying – not so fine dining

The relationship between country folk and townies (other than bank managers and accountants) has often been portrayed as problematic. The lore of the land isn’t always honoured by urban couch potatoes and other metropolitan vegetables. That’s sometimes the perception held by farmers and people of the land, although events like the town versus country cricket match broke down barriers – even as a number of fences went west. It could be said of course that a bunch of townies like a cricket team enjoyed safety in numbers, whereas one-on-one encounters – like the time Gary, a high school senior and a townie, jacked up a holiday job – could produce more intense eyeball-to-eyeball flashpoints.

The morning was just brightening into day as Gary sat waiting for Merve to arrive to take him to his first job: weed spraying at Kawhia. The nervous young townie had been waiting for some minutes before the sound of a vehicle could be heard accompanied by the whine of tyres on tarseal. The truck, a battered Austin Gypsy, pulled up with a graunch of brakes and Merve hopped out with a casual ‘Howarya?’

He wore a holey black singlet which, Gary soon learnt, left his body on only rare occasions, tattered shorts and gumboots. He had a ruddy complexion with crimson shoulders and biceps, and was chewing a piece of gum that Gary rarely saw renewed in all the time the rookie weed sprayer was to know him.

As this was his first-ever country job Gary approached it with some apprehension, and the drive out to the hills passed in silence broken by the occasional monosyllable. Merve showed the greenhorn townie the drill on how to operate the spray gear. His main job was to feed Merve enough hose so that he could reach the gorse with his spray gun.

Their first assignment was up a steep bank above a side road near Kawhia. Gary soon became familiar with the distant, sinister chugga-chugga of the pump below, and the bellowed orders from further up the hill. At times Merve was completely enveloped in a spectacular cloud of spray emerging from the gun. From 50 yards it was possible to catch wafts of the not unpleasant smell of the hormone weedkiller as it drifted on the breeze. It corroded clothing rapidly, which explained Merve’s tattered mocker, and the holes that soon developed in Gary’s singlet. If ‘the boy’ got his orders wrong, perhaps pulling in the hose instead of feeding it out, Merve let him know at long range with a string of powerful curses.

Finally the job was finished, and Gary was amazed at how quickly the time had passed.

‘That’ll fix the bastard,’ said Merve as they reeled in the hose and packed up the gear.

Several more jobs were completed that day. At times Gary could pause and sense the soft breeze on his body and take in the peaceful countryside that led down to the harbour. Well after the sun had set in a blaze of crimson over the harbour they headed into Kawhia township and arrived at a small bach tucked up a side street. Some gear was unloaded, including food.

‘I’ll go and get a dozen down at the pub,’ Merve said, ‘and you can get the grub ready if you like.’ Like a fool, Gary didn’t question his instructions but decided to have a go, although he knew little about cooking.

Indeed Gary remained somewhat traumatised by the time he managed to blow up a pressure cooker full of vegetables at a school camp; he’d insisted that the element be left on high, after the revolutionary new knob thing had been eased into its position on top of the pot lid. Pressure cookers were almost as pivotal a breakthrough back then as the microwave oven in more recent times, but with silver beet dangling from the light bulbs over the stove and a hundred peas smudging the ceiling like large green fly dirt, Gary didn’t feel as if he was part of culinary history. He just felt humiliated.

In the Kawhia bach, Gary tentatively peeled some potatoes and onions, sliced up a cabbage and a handful of carrots and placed the lot in a large saucepan on the stove where they boiled furiously for quite some time. Meanwhile he put the chops in some water on a much smaller element on the stove, where they did little more than soak for the same duration. He decided to leave a small pressure cooker sitting on the shelf. With both elements turned on, the lights in the already dim hut dipped lower, and the radio on the shelf went off altogether. He waited in nervous silence, and then had a welcome shower in lukewarm water.

Gary had just finished inspecting the vegetables when Merve bowled in with a dozen and a sack of something under his arm. He made straight for the toilet. ‘What’s cooking?’ he yelled above the gushing of urine. ‘Smells good and I’m bloody hungry.’

Gary gulped. The vegetables were unrecognisable. Wisps of onion and cabbage floated to the surface, the smaller potatoes were cooked to a mash while the larger ones had similar exteriors but solid cores. The chops were browning nicely on the outside, but a fork refused to penetrate their raw interiors.

Merve emerged and lifted the saucepan lid. ‘Jesus,’ he said softly.

One thing Gary had learnt about Merve was that he could be totally unpredictable. This time, instead of letting fly with colourful four-letter words, he grabbed a hunk of stale bread and opened two bottles of beer. Relieved, Gary joined him, filled his glass and plied Merve for yarns to take his mind off the meal, which was now a total write-off.

As the night wore on his face got ruddier, his speech became more slurred and the yarns became more fantastic as empty bottles sprang up all over the fly dirt-covered table. Sometime after midnight, Merve appeared to have forgotten completely about the meal. He crashed onto a protesting bedstead and began snoring immediately. Gary found another mattress as far from the din as possible.

At about two in the morning Gary woke and peered through a curtain into the kitchen. There, silhouetted against the small light globe was Merve, a macabre figure in his singlet, tucking into the ruined chops and veges without a word of complaint.

Gary was woken before dawn by another commotion in the kitchen. A dull thud preceded a strong smell of burning electrics. A waft of black smoke hovered, as Merve unleashed a string of oaths and curses. Had he encountered burglars? The dull thud sounded like a fist connecting with a head. Gary had heard something like it while watching senior rugby.

As the smoke haze lifted, Gary found Merve spread-eagled on a splintered chair. His singlet seemed to have developed dozens of new holes. Closer inspection showed that he was bejewelled with opened mussels.

‘Bloody hell,’ Merve offered as Gary helped him to his feet.

Merve, in his hung-over state, had been in the process of preparing a breakfast of steamed mussels. A round of toast would complement the meal, Merve thought. Although he had been aware of the fact that the electrical plug of the toaster had somehow flopped into Gary’s stew, he only considered the implications as he was plugging it in. Merve’s own wiring had been compromised by one beer too many. The subsequent blow-out was dull but devastating enough to knock Merve off his pins and see him collapse backwards on to the chair. As he went down he had the presence of mind to try to arrest his fall by latching onto the pot of mussels, which, gravity being what it is, saw the succulent bivalves accompany him to the floor via the flattened chair.

‘Bloody hell,’ Merve reiterated, as he gathered up the mussels and presented them as a welcome, if smoky, breakfast. The compromised circuitry of the bach seemed to have a positive outcome. The radio started blaring unbidden, the lights, after flashing on and off like Christmas decorations, settled into a steady, glaring mode. The stove elements blazed red, again unbidden, and the hot water in the shower was as intense as a Rotorua geyser.

More than that, Merve’s kitchen mishap provided a bonding agent. After his own pressure cooker debacle and the previous evening’s meal from hell, Gary could relate to the situation. As they turned their backs on the charred mussels and a bach that now boasted excellent electrics, Merve and Gary laughed about their shared culinary calamities. Gary was no longer referred to as ‘boy’. The weed-spraying pump now chugged out a pleasant sound that seemed at one with the cry of tui and kereru and the keen, whistling breeze. And the long-range curses became fewer and farther between.

Merve had even renewed his chewing gum and was now sporting a pristine singlet. Gary might be a townie couch potato, Merve mused, and he sure as hell couldn’t cook spuds, but he was quite capable of coming to grief in the kitchen – just like any country bloke. Perhaps they needed to celebrate the fact, Merve thought. Another dozen after work might do it.