5

Do your gumboots lose their flavour (in the cowshed overnight)?

Country folk like to celebrate. They may have a reputation in some quarters for being chronic whingers – wool prices are either too low, or too high. The river levels likewise. The weather lows are too persistent, bringing too much rain, or there’s nothing but highs bringing the threat of drought. But when country folk kick up their heels the whole district hears about it. They can’t miss the cacophony as decibel levels throb out from community halls, across the plains and into the hills.

There was the time Old Man Reddish was due to crack his century. He was about to hit the Big Ten-oh after fighting in two wars (and too many melées outside the town piecart), enduring the Great Depression (‘What’s so great about the Depression?’ he used to say when rounding up scrawny stock), and generally riding out the vicissitudes that life as a Northland farmer can visit upon a man.

It was about this time that the Labour Government removed farming subsidies. That was a sea change and an emotional landslide for many farmers, who now saw themselves pitted against the pitiless forces of ‘the market’. A deep depression settled over agrarian New Zealand. The weather packed up as well.

So the good folk of the district organised a knees-up. They needed only half an excuse to throw their troubles in their old kit bag and get down to the hall on a Saturday night. Old Man Reddish’s century would do just fine. A ‘do’ was organised around the coming of age of one of the district’s most recognisable names. Not that anyone could recall seeing the old man in a while.

Willem van der Hout was on the organising committee and the logical choice as barman. He had pumped suds for 20 years at the Railway Hotel (there was no railway, just an understanding that in the Kiwi scheme of things every rural town had a Railway Hotel). Willem was also rounded up to supervise aspects of the spread – the several tons of food that appeared on trestles after the supper waltz. Several committee members were not so sure about his appointment. Willem had his primitive moments. He could be blunt to the point of boorishness and tended to throw his weight around, along with that of butchered animals.

He was a traditional provider of food for his wife and eight children. Caveman-like, in fact. Often he’d leave freshly butchered and bloody meat on the bench and his dutiful wife would turn it into the focus of the evening meal. Once, when the Jehovah’s Witnesses came calling and his wife had allowed them to doom and gloom their way into the kitchen, Willem threw the calf’s liver destined for dinner onto the bench with an aggressive rugby pass. The steaming, freshly-plucked offal slid gruesomely along the terrazzo and plopped into the sink, where it continued to ooze and steam.

The Witnesses beat a hasty retreat, dropping copies of Awake and Watchtower as they went.

They repaired to the next farm down the road, Trevor Lampp’s place. At least Trevor took the time of day between milkings to debate the meaning of life and the inevitability of death, although when it came to the afterlife he was a sceptic. He had seen too much carnage to ascribe to the view that there was a place in Heaven for farmers who destroyed God’s creatures simply to make a fast buck.

That buck had been slowed considerably by Rogernomics in the 1980s, and Trevor was itching to kick up his heels at a shindig and forget for a while. At least Trevor wasn’t about to be found hanging by his heels, unless life imitated art and certain aspects of Animal Farm became reality. That would be all the local farmers needed.

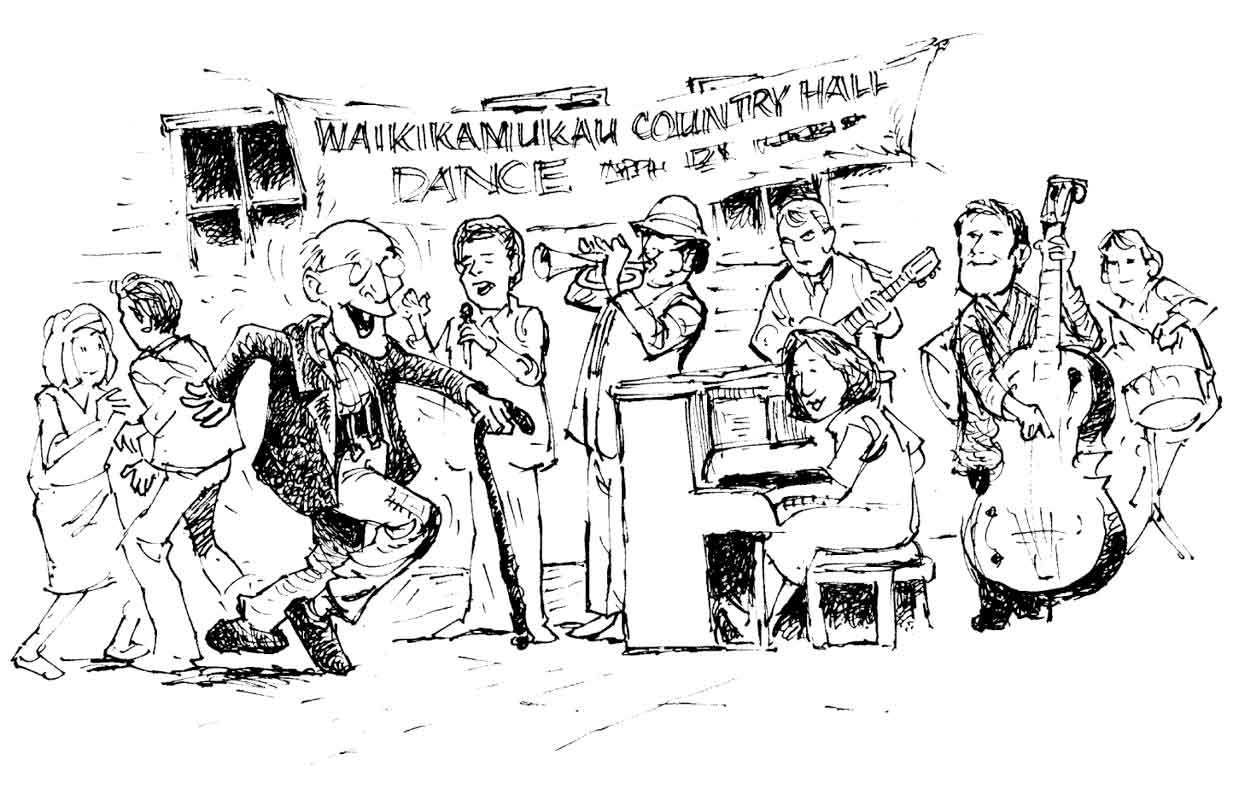

Trevor’s allocated role in organising the do for Old Man Reddish was to jack up the music. He was well-placed to do so. He was the leader of a rural band (some called it an orchestra) known as the Six Seasons or the Trevor Lampp Orchestra. It had started life as the Four Seasons, but someone reckoned an American group had flogged the name. Trevor doubted that very much but, rather than incur lawsuits – and because there were always six members of his Four Seasons (named for the weather rather than the number of musicians) – the band became the Six Seasons.

A sextet it remained and despite slurs alluding to Trevor’s motivation for cobbling the band together in the first place, there was little likelihood of rock’n’roll groupies showing up. Trevor, who played the trumpet, boasted in an unguarded moment that one or two encounters with the opposite sex beyond a peck on the cheek and a pick at a woman’s pavlova had befallen him. So there may have been some sex in the sextet.

But farmers understood those things better than townies. The mechanics at least. Rural kids saw calves being born. They realised early on that when the bull served the cows they weren’t playing bovine tennis. But farmers also knew that a few too many complimentary beers could inflame agrarian desires to equal those of city slickers and swingers, or town bikes and the cyclists who rode them. They weren’t prudes.

The do for Old Man Reddish had little to do with prudes, city slickers and townies, unless you counted the bunch of itinerant farm labourers and fruit pickers who were, inevitably, invited to the hall party simply because rural folk were generous and inclusive. And this despite the fact that a group of fruit pickers living in a farm cottage on Russ Buckley’s property had been the victims of a home invasion a few weeks earlier. A welcome-to-the-district gesture – an impromptu, spontaneous raiding party of well-meaning local farmers – had seen the cottage inundated by ruddy-faced, beer-bearing blokes and their beaming, pavlova-twirling wives.

The itinerant fruit pickers, city types who had experienced burglars and worse first-hand, reacted grimly. One wild-eyed, spike-haired youth grabbed his sawn-off shotgun as the friendly farmers stormed the cottage, and pumped a round or two into the roof. The welcome party scattered as plaster from the ceiling flaked down on the shattered pavlova – the women had dropped everything and run. Someone said that at least the blokes had dived out the windows with their bottles of DB Brown still secure under their armpits.

That had been an isolated incident. Apologies, and more pavlovas, were presented and firm handshakes offered all round. No charges were pressed by either party. Certainly now, as the hall began jumping, the incident was assigned to the back-burner. As Russ Buckley fired up his barbecue out the back, it was the matter of celebrating Old Man Reddish’s unique milestone that provided the focus. Sausages, chops and steak sizzled with a friendly sound and the only jarring note was struck when Willem van der Hout’s offal bangers did in fact explode on the hot plate.

Inside, barman Willem kept the drinks flowing. Sure, the punch was spiked but that was common knowledge, and no spike-haired fruit picker was punched.

The Six Seasons cranked things up from the colourfully decorated stage. ‘Cherry pink and apple blossom white’, featuring Trevor’s trumpet solo, saw a swathe of younger males skidding across the powdered floor towards the flotilla of even younger sheilas itching at the prospect of getting their legs working. Older blokes swaggered with that distinctive rural gait borne of avoiding cowpats and discarded slinks, as they approached the real women and asked for a dance.

One old gent, hobbling with a walking stick but distinguished in a pinstripe suit, advanced on the belle-of-the-ball c.1937, Gladys Finch. Despite the walking stick, they danced a slow waltz in their own time, cutting a dash and setting tongues wagging.

According to some observers, the swashbuckler with the walking stick was Old Man Reddish. That couldn’t be, retorted others. Old Man Reddish, more a Swanndri and gumboots man even at social functions, would never be seen dead in a suit. And if he couldn’t walk under his own steam he wouldn’t walk at all. Walking sticks were for pansies.

Mind you, when the Six Seasons cranked up their version of the twist, the hip-swivelling American dance that had swept the Western world years earlier – and was sweeping Northland now – many older folk quit the dance floor. Not Old Man Reddish though – if that was who he was. He flung his walking stick out of harm’s way and, although Gladys Finch looked horrified, made like a skeletal Chubby Checker, his bones grinding to the beat.

Local farmers loved the twist. It was time to deny the clutches of wives, break the waltz clinch, and stand alone and make a bit of a Joe of yourself. Most twisted like blokes trying to put out a grass fire, or trying to obliterate evidence of cigarette butts at a time when wives were beginning to regard smoking as just another dirty habit. The twist was a levelling dance. It brought you down to earth. They reckon that only chiropractors ever refused to do the twist. At the community hall even the local country school headmaster, a strutting, opinionated twerp, gained new respect as he twisted to his heart’s content, like some sort of academic dervish.

The twist took no prisoners. It could wipe you out, although farmers with bad backs reckoned their backs were back to normal after a hard night’s gyration and twirling. Not that the Six Seasons’ twist bracket went on for too long, but it continued long enough to shake loose the vertebrae of those farmers who swore they had never had bad backs.

Old Man Reddish – or whoever it was in the pinstriped suit – bit the dust. Gladys Finch, adopting a rugby prop forward’s posture, escorted him wincing to the sidelines, his dancing night over. The tongues wagged again. That clinched it. Old Man Reddish would never be seen dead relying on the support of a woman. And certainly not in a physical sense with Gladys Finch doing her Kevin Skinner impersonation.

So where was the real Old Man Reddish? Someone said they saw an old codger swathed in blankets sitting near the beer keg. Another reckoned the guy in the wheelchair near the door to the supper room must be the former nonagenarian. Willem van der Hout reckoned he’d served an old geezer who looked a bit like Old Man Reddish a double whiskey, but then most old men, after a few double whiskies under your own belt, tended to look the same.

The hall was now pulsating like a cruise liner defying the doldrums. A guest vocalist yodelled a piercing version of Slim Whitman’s ‘Rose Marie’. Soon everyone seemed to be yodelling. The sound cut into the night, sped across the plains and set off a hundred dogs, which bayed as much at the siren wail from the hall as the rising full moon. Willem kept pumping out the grog, even as he attempted in his loud, blunt voice to coordinate the assembly of the supper. Young men still skated across the floor until, with the powdery residue gone, they began nose-diving. Who would want to take such partners for the supper waltz? One young idiot threw pavlova on the floor to enable the skidding to continue a little longer.

The Six Seasons’ final offering before the supper waltz broke with tradition. The most risqué tune they’d played was a version of ‘Does your chewing gum lose its flavour on the bedpost overnight?’ The thought was expressed that with Trevor handling the vocals, there might have been more than chewing gum on the bed-post. Now, in a nod to modern music, the Six Seasons launched into Elvis Presley’s ‘Jailhouse Rock’. Des the drummer slammed out an alienating backbeat. Molly, on the piano, transported as she squirmed to the pagan rock rhythm, thrashed out chords propelled by hands that had cupped one too many Pimm’s Number Ones.

Waltzers stopped in their tracks. You couldn’t waltz to ‘Jailhouse Rock’. Dancers couldn’t even do the twist to the rhythm conjured up by Trevor and his Six Seasons. One of the itinerant fruit pickers made a grab for the microphone and, after a brief arm-wrestle with Trevor, won. The fruit picker growled, gyrated from the waist down and set off a polarising response.

Most of the dancers would have accepted a lively version of ‘Ten Guitars’ or ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky’, but a certain rural conservatism was aroused. ‘Down with this sort of thing’ sentiments were expressed. The townie tectonic plate was creating friction along the country fault line.

Someone threw a sausage roll, another a string of saveloys. As the fractured sounds of ‘Jailhouse Rock’ boomed and the provocative pelvis-thrusting singer spat out his invective, the mellow, if boisterous, mood wavered. In the corner of the hall where the itinerant fruit pickers and farm labourers had taken up noisy station, chairs cartwheeled, tables tumbled, and an old man could be seen applying a firm headlock to a young spike-haired leerer. The sight had a sobering effect, but soon the troublesome element was driven from the hall.

‘We’d like to thank Old Man Reddish for dealing to the troublemakers,’ Trevor announced from the stage, which he had regained after the Elvis Presley wannabe was jostled away and locked in the ladies’ toilet. A soothing version of Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’ soon followed with Trevor’s trumpet coaxing dancers back onto the floor.

Meanwhile, beyond the community hall, the fruit pickers and farm labourers sparked sundry altercations as they headed for town. The RD man’s van was sideswiped, a gate was thrown open at Russ Buckley’s, and a full bottle of DB Brown hit an outhouse that apparently belonged to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The most fitting touch was when another bottle smashed the windscreen of a car at 207 Upland Road – the fruit pickers’ cottage. Reports have it that when the ten-strong posse hit town they were immediately subdued at the piecart by members of the Old Boys under-21 rugby team, who were buoyed by an unexpected win over Northern Juniors – and shots of tequila.

They were the only shots that rang out. The sawn-off shotgun was back in the cottage. Those were the days before marauding packs were armed to the teeth.

Back at the hall, ‘My Way’ segued into the supper waltz. The warm, familiar rhythm of ‘Some Enchanted Evening’ saw Trevor blow his most sincere and sinuous offering. His trumpet seemed to retract into the fabric of a good night out for all. Willem closed the bar with a blunt announcement. The supper was attacked. Trestles groaned with food. High levels of chatter tripped out the doors and windows and set the cows lowing in anticipation of an early milking. Chatter turned to gales of laughter when the word went round. That wasn’t Old Man Reddish who applied the headlock that effectively sent the fruit-picking usurpers scampering. That was his son, 70-year-old Ivan, who could, after a hard night, look much older than he really was.

Old Man Reddish, the centenarian, the raison d’être for one of the most uproarious parties in the district’s history, had been dead for 20 years. No wonder no one had seen him for a while.

Anyway, several partygoers were of the opinion that the function served as a farewell for Willem van der Hout. ‘Wishful thinking,’ other knees-uppers reckoned. Farmers, in general, were not squeamish, but when Willem bowled a pig’s head across the supper room floor (followed by the blunt instruction that it become an integral part of the boil-up), several of the more sensitive helpers said that it wouldn’t be the end of the world if Willem decided to leave the district.