CHAPTER TWO

‘If I’d known I was going to live this long,

I’d have taken better care of myself!’

New Orleans Jazz Musician

EUBIE BLAKE

on reaching his 100th birthday

The human body can be compared to a machine – it has fuel, an air intake, lots of small motors, a body and a transmission system. However, it is greater than a machine, because it is self-regulating and self-repairing.

The body normally obtains its energy by burning a mixture of fats and carbohy-drates, but it can also burn alcohol, and in cases of extreme starvation it will burn protein. The energy production process, known as respiration, takes place in every living cell. As the hydrocarbon units are split up, they are combined with oxygen, so that the end-products are water, carbon dioxide and energy. The energy is used to make ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which can then be used for any process in the cell which requires energy. The muscle cells need energy for muscular contrac-tion, so that is where most of the respiration goes on when we are running. Because oxygen is involved, it is called Aerobic Respiration.

Energy can be produced without the use of oxygen and the by-product of the breakdown of sugars is lactic acid (otherwise known as blood lactate). This substance is poisonous to the cells, and unless oxygen is available to oxidise away the lactic acid, the muscles will be unable to work. The amount of oxygen needed to get rid of the lactic acid is known as ‘oxygen debt’.

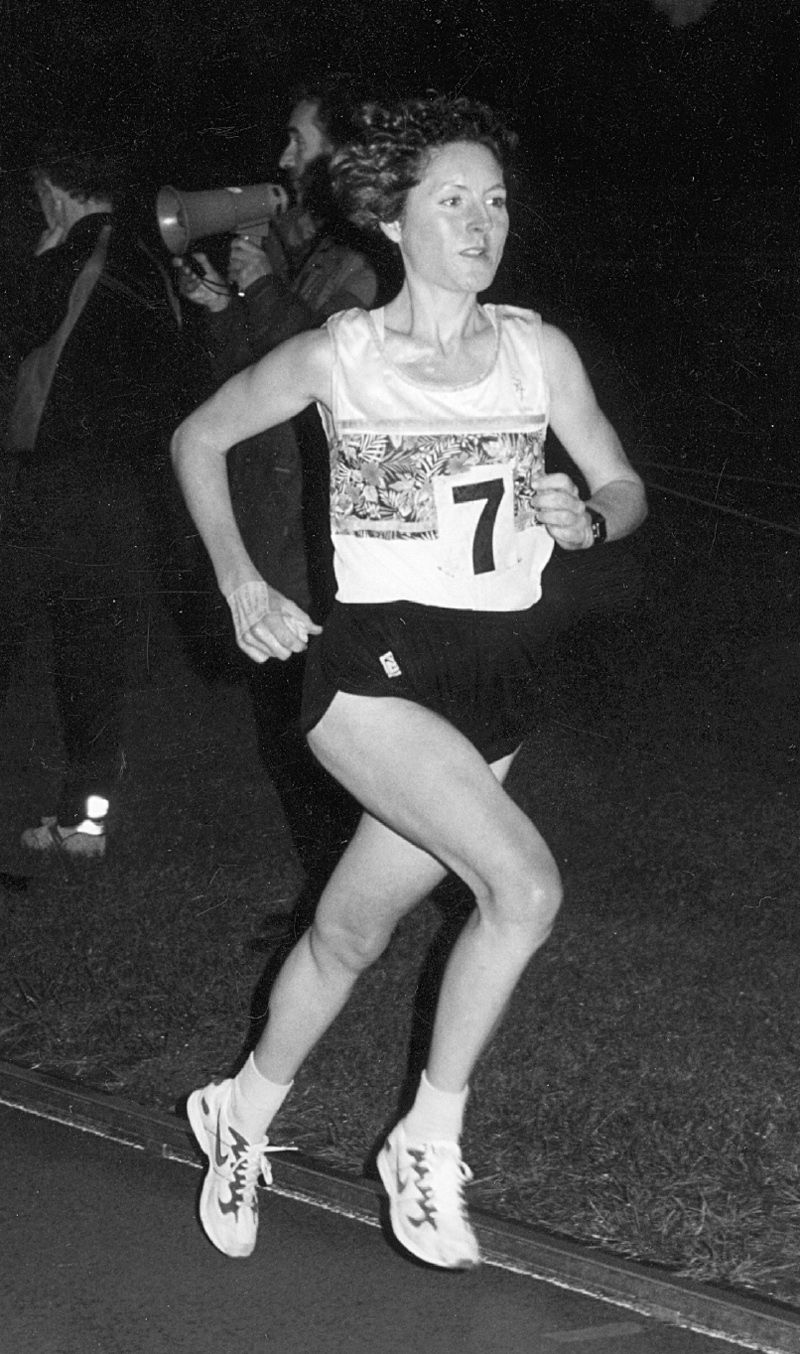

Alison Fletcher - silver medallist in the World Veteran Championships

The air is drawn into the lungs, via the nose and mouth, by the action of the chest muscles and the diaphragm. In the lungs, an exchange of gases takes place. Blood pumped from the heart passes in tiny capillary blood vessels through the thin walls of the alveoli, which are the ultimate sub-divisions of the lung chambers. In a second or two the red blood cells become fully saturated with oxygen, giving up the carbon dioxide which they were carrying. The haemo-globin in the red cells has a very strong affinity for oxygen, so it carries oxygen to all the cells of the bodies, via the arteries, the arterioles and the capillaries. The rate at which it delivers the oxygen depends largely on the capacity of the pump, which is the heart. The heart muscle is very elastic, and it can increase the stroke volume (the volume of blood pumped at each beat) as well as the rate of the heart beat.

Movement is brought about by the contraction of muscle fibres. The fibres are arranged in bundles and unless you are making a huge effort, not all the fibres in a bundle are brought into action at the same time. Part of the training process is ‘educating’ the muscles, so that when necessary all the muscle fibres can be recruited at the same time. Conversely, the lower the proportion of fibres which are working, the less fuel and oxygen are used, so part of the skill of running lies in running efficiently and economically, using only the essential muscles.

The force from the contracting muscles pulls on the tendons, which are attached to movable bones. When the front part of the foot is in contact with the ground, the contraction of extensor muscles around the hip, knee and ankle raises the heel and the whole body. At the same time the back leg is being brought through from behind and the centre of gravity is moving forwards. Other muscles are contracting so as to keep the non-moving parts of the body rigid. If you did not have strong back muscles, your chest would be pulled forwards as your knee is brought up. It is because the human body is not rigid like a car that you need to have a strong all-round muscular system.

As your front foot hits the ground there is an impact shock. If you are over-striding this may actually slow you down, but in any case there is a shock in a vertical plane which has to be absorbed. We have built-in ‘springs’ in the arches of our feet and in elastic tendons in ankle and knee, which are compressed slightly when your foot plants and then return the energy so that you bounce a little. This pogo-stick effect is shown to perfection in the kangaroo, but even in humans it makes the body’s running action more efficient. This is the reason why you need to get your stride length just right for each speed. The inexperienced runner has very few built-in shock absorbers and tends to slap the ground rather hard, while the experienced and stylish runner glides along with little apparent effort.

Is there such a thing as a ‘correct’ foot action? The answer is that everyone is different. The faster you run, the more you tend to run on your toes, to get a long stride. It is very difficult to change your stride length – so you are better off choosing the distance which best suits your stride.

As in a car, the chassis tends to slow you down. If you have a heavy chassis powered by a small engine you cannot go very fast. A reduction of 10% in weight will give you a 10% increase in speed, so if a 60kg person loses 6kg, he can expect to improve by 10%, which is 36 seconds a mile for a six-minute miler.

Because a bit of weight loss brings a big improvement, it is tempting to think that a bigger weight loss will bring even more improvement, but this is not the case. Once your body fat is down to its safe limit (somewhere around 8% for men, 12% for women), extra weight loss can be damaging, either because you break down protein or because it affects your immune system.

There is little in the way of skill or technique involved in distance running. Success depends on a combination of natural ability, training and mental attitude, and of these three, natural ability far outweighs the other two in deciding the results. We would say that success depends 80% on natural ability, with training making up at least 15% of the remainder, and mental attitude accounting for less than 5%. If you put two people of equal ability into a 10k race, with roughly equal amounts of training behind them, the highly motivated one, pushing himself really hard, might finish a minute ahead of the other, but probably not more than two minutes, which represents about 5% of the running time.

The body’s potential may not emerge for quite a long time, if the person has not kept fit since their schooldays. Excess weight, carried as fat, not only makes running more difficult, it also causes people to overheat, so making them more uncomfortable and slowing them down.

Whether you are a ‘natural sportsman’ or not has nothing to do with it. The so-called natural sportsman always has good eyesight and good hand-eye co-ordination, but these factors have no bearing on running success. Some of the best runners are hopeless at ball games and have channelled their sporting ambition into the one thing they can do well, while others are good at ball games and could have excelled in a number of sports.

What does matter is muscle fibre type. The bundles of fibres which make up our muscles contain varying proportions of ‘slow twitch’ and ‘fast twitch’ fibes, as well as some which are intermediate and may by training become fast- or slow-twitch. Sprinters’ muscles may contain over 75% of the fast twitch type, whereas the muscles of marathon runners are mostly of the slow twitch type.

Middle distance runners, who run 800m or 1500m on the track contain roughly equal amounts and by training may shift in one direction or the other, which explains why someone like Steve Ovett could perform well at 400m or in the half marathon. If you are a natural sprinter, with mostly fast-twitch fibres, you are never going to make a good long-distance runner, and vice-versa. There are two ways of finding out – either by having a muscle biopsy done or by trying a range of events in your first year. If you find that the shorter the distance you run, the better you do, then you should concentrate on short-distance events. If you have always been lacking in natural speed you probably have more slow-twitch fibres and should go for the longer events.

There are many other factors involved in that quality known as ‘natural ability’. Body weight, relative to your height, is one of the most significant of these. Since running is simply a matter of carrying your own weight over a distance, it is obvious that that those who are light in weight have less to carry – and that makes a lot of difference. In horse-racing, carrying an extra seven pounds more or less has a marked effect on a horse’s performance – and the horse may weigh five hundred pounds – so how much more it affects the way humans run.

A quick way of finding out where you stand is by working out your Body Mass Index. Divide your weight in kilos by your height in centimetres. A 60kg man who is 180cm in height would have a BMI of 60/180, which is 0.333 kg/cm. A short squat man, weighing 80kg and only 160cm tall would have a BMI of 0.5 kg/cm. Other things being equal, the lower the BMI, the easier it will be to run. However, a really skeletal underweight person would not be a good runner, because most of his weight would be bone, with no muscle to propel it.

An obvious factor here is how much fat you are carrying. Fat is literally dead weight, because it is not being used to hold you up or move you forward, as muscle is. Another parameter for measuring your efficiency as a runner is the measurement of your percentage of body fat. This can be estimated by taking pinches of skin in various places around the body and measuring the thickness with calipers. The simplest way is to take a pinch of skin in your midriff, just above your hip bone. Roughly speaking, if the pinch is 10 mm thick, you have 10%body fat; if it’s 20mm thick, you have 20%, and so on. Good male runners have no more than 10% body fat, good female runners 13%, but within the population in general, figures of 20% for men and 25% for women are not uncommon.

If you have not taken exercise for years you may well be carrying extra fat, which makes it more difficult for you to run, and therefore hides your real ability. We have already mentioined Keith Anderson, but there is an even more dramatic example in the Irish-Canadian marathon runner, Pete Maher. Pete had been a good runner in his youth, but in his twenties he had taken to drink and ballooned up to carrying sixteen or seventeen stone on his six-foot frame. He was watching the World Championships marathon in a bar somewhere, and said to his mates: ‘I could do that, you know. I used to be a runner.’ Their replies were along the lines of: ‘In yer dreams. You couldn’t run a hundred yards, you fat slob.’ Their comments stung him to such an extent that he stopped drinking, took up running again, and he not only made the Irish team for the next Olympics, he led the Olympic marathon field for about twenty miles.

However, even if you are fairly slim and long-legged, with a goodish proportion of slow-twitch fibres, there is no guarantee that you will be a good long-distance runner. What we cannot see are the mechanisms inside. First of all you need a robust skeletal system, with strong bones and joints, which can withstand the impact of running, supported by strong ligaments to hold the joints in place. You need strong muscles and tendons, with a rich blood supply. You need a good strong heart, healthy lungs and a good system of arteries and veins to carry the blood to the muscles and back again. At a deeper level still you need efficient cell chemistry for converting glucose into the energy the muscles require. You need a balanced and responsive hormone system, which will react to stress by pumping out the hormones your body needs to perform at a high level.

The more you go into the physiology of exercise, the more complex it becomes. Knowing a lot about it doesn’t make you run any faster, but sometimes it helps to understand why certain types of training are recommended.

Ahmed Amraoui - hard training pushes back the years

Fitness really means ‘suitablity’. It is very specific. A man who has the fitness to run a good 400m would not have the fitness to run a good marathon. A man who is fit for swimming would not be fit for mountain climbing. A man who is fit enough to run a marathon might find himself quite unfit for downhill skiing, and so on. However, we would probably agree that true fitness includes the following main points:

Not carrying a lot of fat.

Not getting breathless while walking fast uphill.

Able to maintain steady physical exercise for a couple of hours without needing to rest.

Not feeling stiff the morning after a day’s exercise.

Being able to perform your chosen sport several times a week.

To these we might add the following, which might come under ‘health’, rather than ‘fitness’:

Having a good appetite.

Sleeping well and waking up refreshed.

No stiff joints or aching bones.

Having a full range of movement for normal activities.

Having enough strength to cope with everyday needs.

While we would expect that most runners would answer well to all these criteria, they would not define ‘fitness’ in the running sense. A thirty-minute 10k runner would give the same answers as a forty-five-minute runner, but that does not mean that they are equally fit.

When someone says to another runner: ‘Are you fit, then?’, he means: ‘Are you as fit as you would like to be?’, or ‘Are you at your best possible state of fitness for your event?’

The answer is almost invariably: ‘No, not really,’ quickly followed by a string of excuses (or ‘reasons’ as they are called when you are talking about yourself).

Full fitness, to a sportsman or woman, means being able to perform his event to his maximum potential at that time, so unless you have had an unbroken period of hard training for the last three months, you are always going to be a little short of full fitness. Of course ‘hard training’ means different things to different people. If Bruce runs less than 30 miles in a week, he regards it as a poor week, and if over 40, it’s a good week; an international runner would regard anything under 70 miles as being an easy week but for someone else, getting up to 20 miles a week for eight weeks in a row might represent seriously hard training.

Fitness is always relative, not absolute. When friends say to you: ‘Are you fit?’, what they really mean is: ‘Are

you at your normal/desired level of fitness?’ If you are fit enough to run 10k in 45 minutes, that would be marvellous if your previous best was 48 minutes, but not so good if you are accustomed to running it in under 30 minutes.

Fitness is not like virginity – either you have it or you don’t – it is like standing on a moving staircase, on the down escalator. If you stand still, you go down, if you make a little effort you stay in the same place, but if you want to get to the top, you have to make a big effort.

Cross-country running is easier on the legs, but no less tough

Richard Barrington has been running for 47 years, 16 of those as a veteran, doing track running, hurdling, cross-country, road and fell-running. His times, which used to be around 50 secs for 400m and 55 secs for 400m hurdles, are now around 60 and 66 seconds, but in those years he has seldom been injured. This must be due in part to his scientific background, which enables him to understand what is going on. Writing in the Journal of Sport and Medicine, 1988, his views can be summarised as follows:

‘In the young body, damaged cells are replaced very quickly, whether they are muscle fibres or red blood cells. As we get older, this regeneration takes place more slowly. Cuts take longer to heal, bruises and strained muscles stay longer and new blood cells are formed more slowly. If we race or train hard, we feel tired for longer.

‘Another change in the body is the loss of elasticity. The elastic protein fibres are gradually replaced by stronger but less elastic proteins. This has the effect of slowing leg speed. The slowdown is even more marked in sprinters, because over time the effect of years of training is to decrease the proportion of fast twitch fibres, with a increase in slow twitch fibres and inelastic connective tissue.

‘A further effect comes directly from years of competition – the accumulation of scar tissue from previous injuries. Those who have competed for many years at one event pick up particular injuries – damaged ankles in triple jumpers, scarred hamstrings in sprinters, battered joints in road runners. This is where the ‘new wave’ runner, who starts injury-free, has an advantage over the ‘old stager’. However, when it comes to running marathons the latter has the advantage of being pre-conditioned by earlier training, so is less likely to develop over-use injuries.’

The problems of injury and how to deal with it are dealt with in Chapter 13, but the conclusions which Richard Barrington comes to cannot be stated too often:

Hard training produces some damage, which takes time to repair.

The older the athlete, the longer this takes.

A day or two of rest or easy running is needed to get over the effects of hard training.

The hormone system is a method of communication through which the body responds to changes. The hormones are chemicals carried in the blood, so they can affect several parts of the body at the same time. Some hormones are produced for a few minutes only, others over days and weeks. As runners, the first hormone we think of is adrenaline, the hormone of ‘flight and fright’ which has a big effect on performance. Adrenaline and noradrenaline bring about an increase in heart rate, a rise in blood pressure, an increase in the level of blood sugar and a diminished sense of pain. It is the production of adrenaline which enables us to perform much better in races than in training. It is the ‘adrenaline rush’ which makes race day exciting.

In response to training, however, other hormones are important. Growth hormone (GH) is vital in stimulating the processes of muscle repair and develop-ment, and one of the things which distinguishes the good athlete from the mediocre is the ability of the good athlete to produce high levels of GH – and thus cope with bigger training loads.

When we look at GH production at different ages, we find, not surprisingly, that the old are less responsive than the young. Researchers at the University of Colorado (Silverman and Mazzeo, Journal of Gerontology, Vol. 51A, 1996) measured the levels of a number of different hormones before and after exercise, comparing trained and untrained people of different ages.

The strange case of Ed Whitlock

More or less everything we have written about inevitable slowing down appears to be contradicted by Ed Whitlock, a seventy-six-year-old English-born Canadian,who lives in Milton, Ontario. In October 2004, aged 73, he ran 2hr54:44 for the Toronto marathon, a world best for over-seventies. In October 2006 he set an over-75 record of 3hr 08:35, again in Toronto. On the track, he won the over-70 5000m and 10000m at the World Veterans Championships, the latter in a record time of 38:04 seconds. At the same age he ran a half-marathon in 80 minutes.

Of course every runner would like to know his secret, but there is no secret. He doesn’t take any magic potions – not even vitamin pills. He doesn’t stretch, he doesn’t do weights or cross-training and he doesn’t do any quality running apart from his races. He continues to maintain a high mileage – running two to three hours a day, over 100 miles a week, something which none of us ‘experts’would recommend. Laboratory tests showed just what one would expect from someone who can run those times – low body-fat and a VO2 max of 52.8ml/kg/min.

Studies of his hormone levels and his haemoglobin showed nothing out of the ordinary. The answer lies in his attitude and in his family background. His mother lived to ninety-three, his father died in his eighties, and his father’s brother lived to 107. It seems likely that Ed Whitlock is one of those people who ages very slowly, and that is why he doesn’t break down or get injured, in spite of his volume of training.

Without those genes, he could not be the success he is, but the genes would not give him success if he didn’t have the will to succeed, the desire to be the best he possibly can be.

He has the ability – he won a World Master’s title at 1,500m when he was 48 – he has the desire and he has found a training method which suits him. That’s all you need.

The pre-exercise level of GH was between 1.0 and 1.4 units (ng/ml) in all the groups. After due precautions they were given an exercise test on a static cycle ergometer, working up to ‘maximal exertion’. After exercise the GH level was 5.6 in untrained young men, but 21.9 in the trained group. In the middle-aged group (age around 45) the figures were 8.6 (untrained) and 19.0 (trained). Even in the elderly group (mid-sixties) the results were quite clear – the levels were 2.8 for the untrained and 11.3 for the trained group. This ability to produce Growth Hormone enables the trained men to respond better to stresses and traumas. Their capacity for growth and repair is much greater.

You will have noticed that even in the untrained men there was a big response to the exercise test – their problem was that this was the only time when they took any exercise! This group of researchers concluded that:

Training can increase the growth hormone response to exercise in the elderly.

This has the benefits of increasing lean muscle, decreasing fat percentage and increasing the capacity of the heart.

Their overall conclusion, looking at a number of different hormones, was that endurance training improved the capacity of the middle-aged and elderly to respond to ‘disruptions in homeostasis’.

If we are looking at this question from the angle of: What is the best way to improve performance?, it is worth mentioning that growth hormone levels are not affected much unless the exercise is quite intense – at least up to Threshold level (ten-mile pace). To get a response from the body you have to stimulate it, and that means doing some of your training at a fast pace – at least 10k pace and preferably 5k pace.

This scientific evidence bears out what runners and coaches have always known – that you have to push yourself hard to produce an effect. At the same time, we have to avoid the breakdown caused by over-training, which is why we advise people to follow a recommended training schedule in the early stages and only to experiment when they have reached a high level of fitness. This is where a heart monitor comes in useful, because you can keep a close watch on your level of training.

However, we must always bear in mind that the best distance runners in the world, the Kenyans and Ethiopians, run faster than anybody without the benefit of scientific knowledge. The best way to get fitter and to find out if you are any good is to get out and start doing something.

When hormones are mentioned, sex is the first thing which comes to mind. You can blame almost anything on hormone levels when it comes to sex. We have all read horror stories about ‘testosterone freaks’ who raise their hormone levels to improve their weightlifting performance and then become uncontrollable sex maniacs. It is a fact that levels of both growth hormone and testosterone (male sex hormone) decline after the age of 40, and falling hormone levels often result in a loss of sex drive. However, recent research at the University of Newcastle, reported in The Observer (23rd May 2000) showed that the effects of ageing can be reversed by hard training, driving up the hormone levels and giving older men more sex drive. Men aged 55–65 who trained more than 40 miles a week were found in this study to have higher levels of both hormones than normal men of a similar age who did no regular exercise.. According to Pat Kendall-Taylor, the Professor of Endocrinology, the runners had four times the level of growth hormone and 25% more testosterone. This is not enough to turn old men into testosterone freaks, but it is enough to make a difference – once you have recovered from your run. Although the study was done on only two groups of ten, the results were statistically significant – and of course they tie up with what we have already pointed out about growth hormone.

By stimulating the production of growth hormone and testosterone, running is doing for men what Hormone Replacement Therapy does for women. Because HRT treatment has only been widely used in the past 20 years, there are still those who harbour doubts about it, but the effects on middle-aged women have been quite striking.By maintaining the levels of the female sex hormones after ovula-tion ceases, HRT keeps women biologically younger, which means that they feel better, look better, have more energy and run faster.

HELEN STOKES

Age: 44 started running at: 36

Occupation: part-time drama teacher, mother of three

Best performances: 10k 44:45 half marathon 1hr38 marathon 3hr38

‘Most of the time my family think I am bonkers and that goes for most of my non-running friends too! What explanation can you offer, as a born-again runner, to those who can’t relate to the satisfaction of sliding through mud, panting up hills or pounding the pavements in sub-zero temperatures?

‘I tell people I started running to prevent me from beating my children and there is a grain of truth in that: childcare and housework have their joys, but for those who are achievement orientated the everyday tasks give little satisfaction. Going for a run is a self-contained activity; you go, you return and there is the accomplish-ment of having achieved something – and of course there is the flexibility of it being a solitary activity requiring no particular venue, which you can fit in at any time.

‘I am in the fortunate position of counting amongst my friends some very good runners: the enthusiasm they have shown over the years for my paltry efforts has been immensely significant. If you are a capable runner you can do so much for those way behind you, just by showing an interest in their problems and their progress. I have never been made to feel that my achievements are unimportant and my ‘triumphs’ have been celebrated with the best of them.

‘There have been interesting moments along the way; I’ve run in all sorts of places, from rural France to Central Park, New York. The most bizarre moment was the ‘nettle sting’ which turned out to be an adder bite. It cleared up with heavy doses of antibiotics, but I’m glad I didn’t see the snake actually making contact! On the plus side, it always makes me smile when I win a prize, because it’s unexpected. Last week I entered a race at the last minute, with no special training, and was first lady.

‘I am proud that I can run quite well, but always wish that I was a bit fitter. I enjoy running with friends and sorting out my problems – I’ve discussed family problems, worked out lessons and debated the ordering of God’s universe. When I see the more ancient ladies and gentlemen running the London marathon I am humbly impressed –and I hope to be there too.’