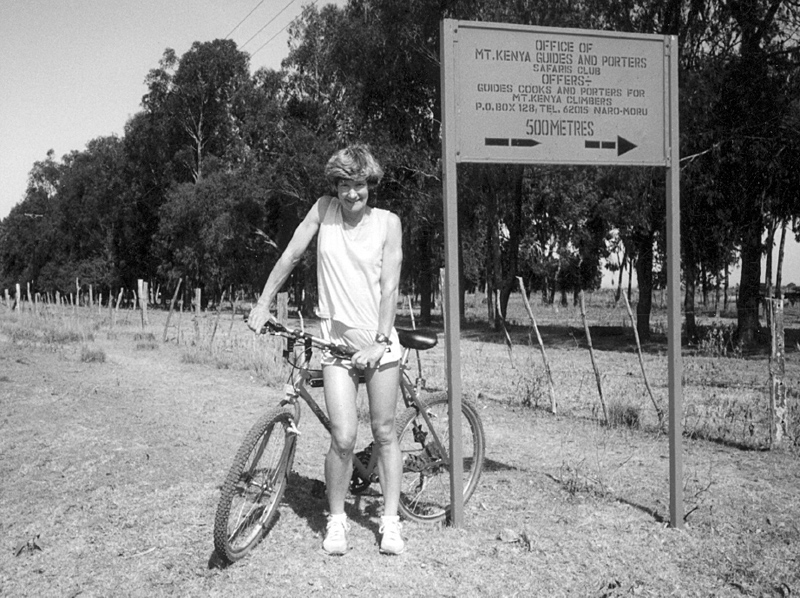

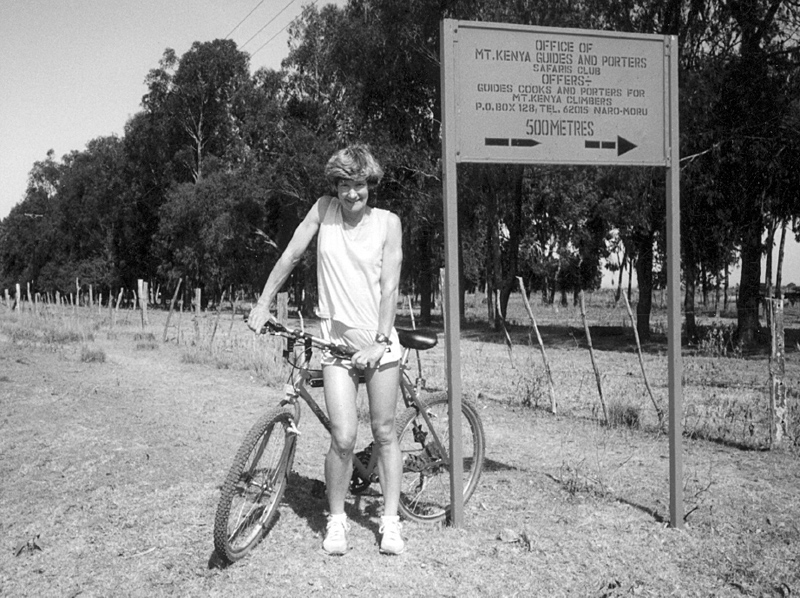

Sue Tulloh — training on the road is good, and so is the mountain bike

CHAPTER FIVE

‘Train first for distance, then for speed’

ARTHUR NEWTON

The simplest way of understanding training is to relate it to the distance you hope to run. If you want to race over 10 kilometres, you first have to build up your endurance to the point where you can cover at least 10 kilometres non-stop (walking is allowed) and then you have to work on your running speed. If you want to run the 10k in under fifty minutes, you have to start by running one kilometre in under five minutes. Getting the right mixture of endurance and speed training is dealt with in the schedules in later chapters.

Remember that the training process consists of Stimulus and Response. When you make an effort, the body will try to adjust so as to cope with that effort, and when it has adjusted you can increase the load a little bit more – either by increasing the distance or by increasing the speed. The human body is amazingly adaptable, but it needs time. The art of coaching lies in choosing the training which gives enough stimulus to have an effect, but not so much that it causes breakdown. If you just go on doing the same thing week after week you will not only get bored, you will cease to improve.

The most efficient way of operating is to vary the training, so that we are working on different aspects of fitness. The first principle, credited to Arthur Newton (see Chapter 3) is: ‘Train first for distance, then for speed’. By walking and jogging, and later by continuous slow running, we strengthen our supporting system. The supporting muscles and ligaments, which keep our skeleton in position, will get stronger. The muscles will increase their fuel storage cpacity and in particular there will be a development of the tiny capillary blood vessels which surround the muscle fibes. This will greatly increase the ability of the blood to get oxygen into the working muscles.

Heavy weight-training may increase your muscle strength and the muscle fibes may get bigger, but it will have no effect on developing this important capillary bed, so all distance runners – even middle distance runners – need a founda-tion of long slow running.

Building up the total distance run each week will have other effects. It will burn up excess fat, reducing your body weight, and it will encourage the leg bones to lay down extra bone material, making the bones stronger and decreasing the risk of osteoporosis. However, this increase has to be gradual, because the shock of the repeated impact of foot on tarmac may cause damage to unprepared bones and joints. The human feet and legs are designed to run, but not to run on tarmac, so you should try to get off the road as much as possible, and if you do have to run on road a lot, make sure that you have good shoes.

‘First and foremost, there is no substitute for properly structured training. Regardless of age, hard intensive work, with suitable recovery periods, is the onlys ure way of improving’

IAN VAUGHAN-ARBUCKLE

To run faster you have, for a start, to increase both your stride length and your rate of striking. This means that you have to drive more strongly and lift your knees higher. To maintain this extra speed needs a greater energy production and of course a greatly increased oxygen intake. You have to breathe harder and more deeply, and your heart has to pump harder to pick up more oxygen per minute. With training, all these capacities will improve. Most of us have enough lung capacity to take in the extra volume of air, but it is the effect of training on the cardiovascular system – the heart and the arteries – which influences our ability to run well.

The good runner has a large strong heart. This is partly due to his genetic background and partly to the training he has done. One thing is certain, that we can all improve our cardiovascular system by training. This can be shown easily by running round a certain course in a certain time and taking the pulse rate before and after. The duration of the timed run should be at least five minutes, but not more than ten minutes.

Let us say, for example, that you decide to run four times around the track –a mile – in seven minutes. For the unfit person this would be a hard effort and his pulse rate would probably go close to its maximum. However, for the fit person who can easily run a mile in under six minutes this pace will be quite easy and the pulse rate will not be as high. Over the years a number of changes have taken place in his body, which have made the seven-minute mile easy. Down in the muscles there has been a huge increase in the number of enzyme molecules which pick up the oxygen from the blood. There has also been a development of the capillary bed, so that the blood flows more easily through the muscles and an increase in the strength and capacity of the heart itself. The heart is a muscle – an exceptional one. It will get stronger with exercise, and the result of all these changes is that a seven-minute mile, which left you puffing and gasping with a pulse rate of a hundred and eighty beats per minutes, can soon be handled comfortably, with the pulse rate rising to less than a hundred and fifty.

Sue Tulloh — training on the road is good, and so is the mountain bike

The secret of success in running (and in most other things) is ‘know thyself’. If you know what your limits are you can set yourself the right targets in racing and training and you can try to extend those limits. The heart monitor is really useful here, because it tells you exactly what is going on inside.

The intensity of your training can be guaged by your heart rate. It is easy enough to measure the pulse rate at rest, but impossible to do so while running unless you have a heart monitor. We used to take pulse rates, manually, for ten seconds immediately after doing a bit of interval work, but it is difficult to be accurate. There is a general guideline which says that your maximum heart rate should be 220 minus your age, but individuals differ enormously. One person’s ‘comfortable’ heart rate is another’s ‘threshold’ rate. Some people can never get their heart rate up to 160, while others have a maximum of over 190 and can run for miles at a rate of over 160.

Measuring heart rate

The best way of doing this is by using a heart rate monitor, but you can take your pulse rate easily by finding either the artery in your wrist, just above the ball of the thumb, or one of the arteries in your neck, either side of your windpipe. Time the number of beats per minute at rest, sitting down; time the pulse rate again after you have warmed up, before you start the timed run, and then take it once again as soon as possible after you have finished.

A lot of people just run as they feel, and you can plan your training entirely along those lines, categorising your pace as ‘easy’, ‘steady’, ‘brisk’, ‘fast’ and ‘very fast’. In terms of racing speed, ‘steady’ is probably your marathon pace, ‘brisk’ is your Threshold (10-mile) pace and ‘fast’ is your 5k or 10k race pace. ‘Very fast’ is when your are accumulating lactic acid very quickly; it is somewhere around your one-mile race pace.

The trouble with this method is that you can never find out whether you are gettng fitter or not, because you have no accurate record of either your speed or your effort level. Races are a guide, of course, but the advent of the wrist-borne GPS enables us to measure improvement far more accurately.

Using a heart monitor you can easily measure your pulse rate at rest, when walking and wh-en jogging (‘easy’ pace). If you run round your fixed course (1–2 miles), timing yourself, at a ‘steady’ pace and later at a brisk pace, you will then have heart rates for different levels of performance.

To get an accurate measure of your maximum heart rate, you should do a thorough warm-up and then do two flat-out runs of about 3 minutes, with only 3 minutes recovery. You will reach your maximum heart rate by the last minute of the second run. If you have a track handy, do it as a 2×800m time trial, trying to run as fast as possible on the first run and trying to equal the speed on the second go.

You now have a set of measurements looking something like this:

Heart rate |

Beats per minute |

Resting |

64 |

Walking |

85 |

Jogging |

110 |

Brisk |

150–160 (after 3 minutes and after 10 minutes) |

Maximum |

180 |

Your range of pulse rate is 116 (the difference between ‘resting’ and ‘maximum’) so...

‘50% effort’ would be 64 (resting) + 58 (50% of 116) which is 122

‘75% effort’ would be 64 + 87, which is 151

‘90% effort’ would be 64 + 105,which is 169

For building endurance and for your recovery runs you will be running at no more than 50% effort.

For improving your running speed you have got to be training at between 75% and 95% effort. To relate these efforts to your performance in races:

75% effort corresponds to ‘threshold pace’ (our ten-mile pace)

90% effort corresponds to your 10km race pace

95% effort corresponds to your 5km race pace

The hard-training athlete will probably put in three hard sessions a week, one at each of these paces, so that he will be working on a ‘hard-easy-hard-easy’-pattern, with a long slow run on the seventh day. For those in the 45–55 age range, two hard sessions a week is probably enough and for the over–55s, one hard session and one long run per week.

The runs at threshold pace may be done without a break, following a warm-up, or they may be done in sections of ten minutes or so at a time, with very short breaks. This is possible because at this pace oxygen is being taken into the muscles as fast as it is being used up. At the higher intensities, however, the oxygen supply is not sufficient and so an ‘oxygen debt’ builds up, in the form of lactic acid. This means that the effort cannot be sustained for very long, and recovery periods are necessary. This type of training can be done in three main ways:

Fartlek: This a Swedish word meaning ‘speed play’. The athlete runs fast for as long as he wants and then slows down to a jog until he is ready for another fast burst. In a 30-minute Fartlek session the athlete might put in 12–15 bursts, lasting 30-60 seconds, with recovery jogs of 60–90 seconds.

Interval Training: This is the most effective type of training and it is used by most of the worlds best runners. The distance run is fixed – usually a multiple of 400m – and so is the recovery time. A typical session for a distance runner might be 15×400m, with 60 seconds jogging recovery between each fast 400. When done on a track, this kind of session tells you exactly how fit you are. A novice runner might start by doing, say, 8×400m with a 2 minute recovery jog, and averaging 90 seconds for his fast laps. Week by week he runs them a bit faster until he is averaging 80 seconds a lap. He can then increase his endurance by increasing the number and cutting down on the recovery, going up to 12×400m with a 90 second recovery, but running them more slowly, say 86 seconds, and then aiming to improve the average speed. Someone aiming at a 5k race would do 4–6km of fast work, whereas a 10k runner might start with 8×800m and work up to 10×1000m, done at 10k speed or a bit faster. (For typical track sessions, see Chapter 8.)

Interval training does not have to be done on a track. A good session on the road is ‘1 minute fast, 1 minute slow’, repeated ten or a dozen times. One of the favourites is ‘pyramids’, where you do 30 seconds fast, 30 seconds slow, 1 minute fast. 1 minute slow, 2 minutes fast, 2 minutes slow, 1 minute fast, 1 minute slow, 30 secs fast, 30 secs slow. If you do three of these pyramids during your run you have done 15 minutes of fast work

Repetition Training: This term is normally applied to training over distances lasting 3 minutes or longer. One might do repetition miles, or 5-minute repetitions or even 10-minute reps, with a fixed recovery time. One of Richard Nerurkar’s best sessions when training for the marathon was 4×3k, with 4–5 minute rest. At the other end of the competitive spectrum, we once saw Phyllis Smith, the 400m runner, do a repetition session before the Olympic Games which consisted of 4×200m on grass with 20-minute recoveries.

British Vets 5k championship

Although this training method has been in use for a long time, no one has expounded the principle more elegantly than Professor Roger Robinson, the man who gave it a name, in his book, Heroes and Sparrows (pub. South-Western Publishing, New Zealand, 1986). Besides representing both England and New Zealand at cross-country, Roger has won the over-forty section of both the New York and the Boston Marathon, as well as World Veterans titles, so he knows what he is talking about.

In the Sausage session you run for set periods of time, making up the route as you go along. The ‘sausages’, or efforts, can be of any period of time from 1 to 15 minutes; they can be all of the same size, or they can be mixed, as in a ‘pyramid’ or ‘up and down’ session. They can be suited to the marathon, e.g. 4×15 mins, to the 10k, e.g. 6×5 mins fast, 3 mins slow, or to the 5k, e.g. alternating one and two-minute efforts, and they are particularly good for cross-country training, because a five-minute fast burst may take you through a variety of terrain.

The sausage session combines the principles of Interval training with the freedom and enjoyment of Fartlek. It is best done in a group, with different people leading each fast burst, but it is also a good way of enlivening a solo run.

You would probably do best to start with one of the ready-made sessions in the book, attuned to your level of ability, but as you get fitter you should plan your own, because everyone is different – some need more speed training, some need more endurance.

The volume of your training is a compromise between what you would like to do, what your body can stand, and how much time you have. Some people put in 10 miles a week of training and race regularly, a lot of club runners put in 30–40 miles a week. Professional distance runners mostly run between 70 and 100 miles a week, and marathon runers up to 150. One of our correspondents, Peter Lea, when training for a 24-hour track race, pushed his training up to 30–35 miles per day –over 200 miles a week, at the age of 52, but this is not something we would usually recommend! Another correspondent, Robin Sykes, who is a former professional coach, pointed out that many of his contemporaries who had run huge mileages on the road when they were young were now waiting for hip replacements, while he himself, who trains 2–3 times a week and works on his flexibility, remains fit and active.

The volume of the training, in terms of so many miles per week or hours per week, must be related first of all to what you have done in the past. Whatever your ambitions may be, it’s no good launching into a 50 mile a week plan if you have not gone over 25 a week for the last six months. Aim to increase your weekly mileage by no more than 5 miles a week or 10% of the pevious week, whichever is the greater, until you get up to your target.

‘I have been training twice a day since the age of 18. Twenty years ago I would average around 110 miles a week, now (at 45) it is between 70 and 80 miles a week.’

MICK MCGEOCH

Introduce ‘quality’ sessions after two or three weeks of steady running, starting with one Fartlek session a week, then adding one interval or repetition session a week. For most veterans, two quality sessions a week is plenty. If you want to work harder, work to a 3-day cycle – Easy, Moderate, Hard, with an interval-type session on the Hard days and a brisk run at Threshold (ten-mile) pace on the Moderate days.

Relate your training pace to the pace of your planned races – if you want to race over 10k, do one session a week at 10k pace, and change your programme every three or four months.

Analyse your motives for running.

Keep a training diary.

Redefine your objectives year by year.

Run for enjoyment.

Run some races.

Join a running club.

Get a coach.

Look after yourself.

Look for variety.

Be flexible.

It is not just the running which matters, it is what you think about when you are running. There are many reasons for taking up running. Let us take a few hypothetical characters, all of them around forty years old, examine their motives and estimate their chances of success.

Howard B. Grate wants to run for his country. He has been a runner since schooldays and joined the local harriers as a teenager. He has always been good; he has won many local road races but he has never reached international level. As he has gets older and his friends have retired, he has continued to train. Now he is eyeing the veteran ranking lists. This is his chance to win a national title and run for his country.

Molly Meanswell worries about what other people think. Some of her friends belong to a gym and they have decided to get fit for a Women’s 10k race, to raise funds for a good cause. Molly has never done any running before, but it is such a good cause – and she doesn’t want to let he friends down – and think of the good it will be doing her!

Steve Welldunn is a natural sportsman. Even at thirty-nine he is slim, flexible, a squash player, a good dancer, turns out for the firm’s cricket-team and ocasionally for the five-a-side team. It was while playing football, in fact, that he noticed that he was puffing a lot more than he did last time he played. When he mentioned this in the bar afterwards, his friend said to him: ‘what do you expect? You can’t expect to keep up with young Robinson – he’s about twenty years younger than you.’ That was it. Steve had always been used to being the best at every sport without trying particularly hard and he wasn’t going to accept being beaten by someone younger. He resolved to take up running and get fit.

Wendy Wate-Loess is not at all sporty, but she does like to look good on the dance floor, and in the last few years the weight has crept up. She has read that running is one of the best ways of losing weight and somebody in her road has started a women’s ‘meet and train’ group. She is worried that the others will be a lot better than her.

Peter Pan, the keep-fit man, is not much good at ball-games either, but he is very organised, very disciplined. He watches his diet, swims twice a week and has a subscription to a gym, where he does two thirty-minute sessions a week. Lately, though, he’s been finding the routine a bit boring and wondering if there might not be other things in life.

What they don’t know, and we don’t know either, is whether they enjoy running and whether they are any good at it.

Our long-term goals, the dreams and ambitions, push us into running, but we need short-term goals to keep things going, and these short-term goals should be achievable targets. If you say to yourself: ‘By this time next year I want to be able to run 10 miles/a stone lighter/under 45 minutes for 10k’, you should then say: ‘In ten weeks time I want to be able to run two miles/3 pounds lighter/running 30 miles a week. When you reach the first target, you set the next one, no longer than three months ahead.

BRUCE: ‘I started my training diary on my twenty-first birthday. I used an ordinary lined exercise book, with one line per day to record the details the time or distance run, the type of training, i.e. steady run, interval training, Fartlek, the details of times, the weather, and how I felt. The latter is very important. If the comments, day after day, read ‘good’, or ‘felt easy’, or ‘good and hard’, then you will have no problem, but if the remarks start to read: ‘tired’, ‘felt sluggish’, ‘legs dead’, then you are overdoing it and need to ease off before you get injured.’

The training diary is an essential part of your running; it is your conscience and your coach. If you want to know how fit you are now compared to six months ago, look at your training diary. How many times a week were you running?How long did you take to get round your regular circuits?

If you want to find out why you are not getting such good results, look at your diary. Do you realise that this is your sixth race in seven weeks and you haven’t had much time for training?

If you want to know whether you are ready to run a marathon, look at your diary. How many runs of over two hours have you done in the last ten weeks?

In your first year of running you will make a lot of progress. The things which once seemed a challenge, like running for half an hour without stopping, have become routine.

You now have to decide whether you want to go further or whether you are quite happy with what you have achieved and just want to stay at that level. Even if the latter is the case, you still need to plan your year. Routine running – say a regular twenty miles a week – is OK, but boring routine is not OK. A slight alteration in your plans, season by season, will provide the stimulus to make your training purposeful.

Fun and Fitness should always be the keynotes. Sometimes you may have to work quite hard to achieve your goals, but the pleasure you get from achieving them will make up for the pain. Running should add enjoyment to your life, not restrict it. Enjoy the freedom of being a runner, of being in control, of being strong and fit. Enjoy the changing seasons, the freshness of the morning, the wind in your face. Whatever speed you run, feel glad that you are able to do it.

‘I don’t structure my training at all. If I feel good, I run fast and if I feel tired, I run slowly.’

JENNY MILLS

If you have an ounce of competitive spirit in you, you will enjoy running against other people, because there will always be someone you can beat. If you are that perfect Buddha-like individual who hates to beat others because it would demean them, you can enjoy running with other people, helping each other to achieve your personal goals. Both attitudes are a great help during the race. The adrenaline which you produce when there are others running around you will help you to run much faster than you thought was possible. Races give you fixed points in your training year, special days to peak for. Without something to work towards it is difficult to maintain one’s enthusiasm.

Some people are clubbable, some are not. Runners tend to be individualists, but that should not prevent you from joining a club. You can get as much or as little from it as you want. At the very least, you will meet people who run regularly and you should be able to find some congenial training partners.

The easiest ways of finding a running club are:

Go to the nearest running shoe shop and ask.

Look in your local newspaper for news of running and maybe ring the sports desk to find the contacts.

Go to a local road race and ask people there.

Buy Runner’s World and see what events are on locally.

Get onto the web and log on to British-Athletics.com. They have full lists of clubs, most of which have websites.

Write to the appropriate Area Association (see Appendix 4 for useful addresses). If you live in a city, there may be several clubs within driving range. It is a good idea to visit two or three in your area and find out what they are like. There are really two main types – the long-established club which is very much into serious competition in road, cross-country and track running and the ‘new wave’ club whose focus is more on running for fitness and enjoyment. Of course there is a lot of overlap; the big clubs often have a joggers section and the new clubs may produce a seriously competitive group, but every club has its own attitude. Some will pressurise you to run in inter-club events – cross-country mob matches, veteran relays – and others never bother to enter a team in anything at all. We suggest that you run with your new club for a few weeks before actually signing up, thus saving recrimination if you don’t see eye-to-eye. The things you should ask are:

Do they have a running track?

Do they have any indoor training facilities?

Do they have any coaches?

Do they have any social organisation ?

Get a coach. We all need someone to share our problems with. Unless you have the perfect partner, you cannot expect him/her to have the same enthusiasm for all your interests. The coach does not have to be someone with a coaching certificate or an England tracksuit – just someone with a bit more experience than you, who is prepared to give you time to talk about your running. We go on learning all the time. The important thing is that the coach understands what your goals are in running and values what you do.

Look after yourself. Remember that you get the benefits of a training session in the recovery period after the session. You expend a lot of energy and lose a lot of fluid when training hard, so get a drink and some carbohydrate food as soon as possible after training. Arrange things so that you have time for a warm-down and a shower after training.

Bear in mind that the older runner cannot get away with things in the way that the young can. Your rate of production of growth hormones is probably lower than it was, so the adjustment and the recovery after hard training will take a bit longer. Give yourself time to stretch after training. Never put in a hard session until you have rcovered from the previous one.

Look for variety. This applies to both training and racing. Boredom is the runners enemy, and much as we love our sport, it is all too easy to get into a training rut of doing the same runs week by week. There are lots of different events all over the country every week. Wherever you go in the world you can find fellow-runners and new places to run.

Be flexible. This means mental flexibility and well as physical. Both are essential. You should certainly work on physical flexibility, by warming up and doing loosening exercises before training and stretching exercises after training. The mental flexibility applies to your ability to adjust your training to the demands of life. We think that the body works to a weekly budget. You don’t have to do your training sessions in exactly the same order as the schedule says, but you should try to fit them in at some time in the week. If you do less one day, don’t worry about it, but try to compensate later on.

DOUGLAS COWIE

Age: 48

Occupation: instructor at sports centre

‘I joined the RAF at the age of 17 and at that time I was a footballer and squash player, but that changed when I met a runner called Bob Wallis, who was coach to Steve Jones. I was coached by Bob for nine years and became a committed runner. I was privileged to be part of an all-inter-national RAF squad during the late seventies and eighties, and we enjoyed great success.

‘The team included people like Steve Jones, Ray Crabb, Roger Clark, Roger Hackney and Julian Goater. Mixing with those guys was all the motivation I required! I was introduced to marathons by Donald McGregor, and I ran thousands of miles with him. For twenty years, from the age of 25 until I was 45, an average week in the winter involved racing on Wednesdays and Saturdays and training twice a day on the other days, except for Sundays which was a two to two-and-a-half hour run. We would do a hill session every week, and a repetition session, such a 4×5 minutes. The total would be over 80 a week, sometimes 90.’ (This was the same routine which brought Steve Jones to 8th place in the Olympic 10000m and a world marathon record a few months late –Ed.)

‘At the moment I feel as fit and healthy as I have ever done in my life. I am convinced that this is due to ‘cross training’. I swim three times a week; I do lengths with a buoy, doing ‘arms only’. It tones up the upper body, but the benefit I’ve felt most in my running is controlled breathing.

‘So far I have done 48 marathons and I want to to 50 before my 51st birthday –the World Vets in Kuala Lumpur in 2003 would be a good one. I also intent to retire from competition and finish at the top – healthy! But, on saying that, I can’t ever see myself not running. I’ve always fancied orienteering. Who knows?’

In 2004, Douglas was selected to be one of the escort runners for the Olympic torch on its journey round the world to the Olympic Stadium in Athens and in 2007 he did the same for the pan-American Games.