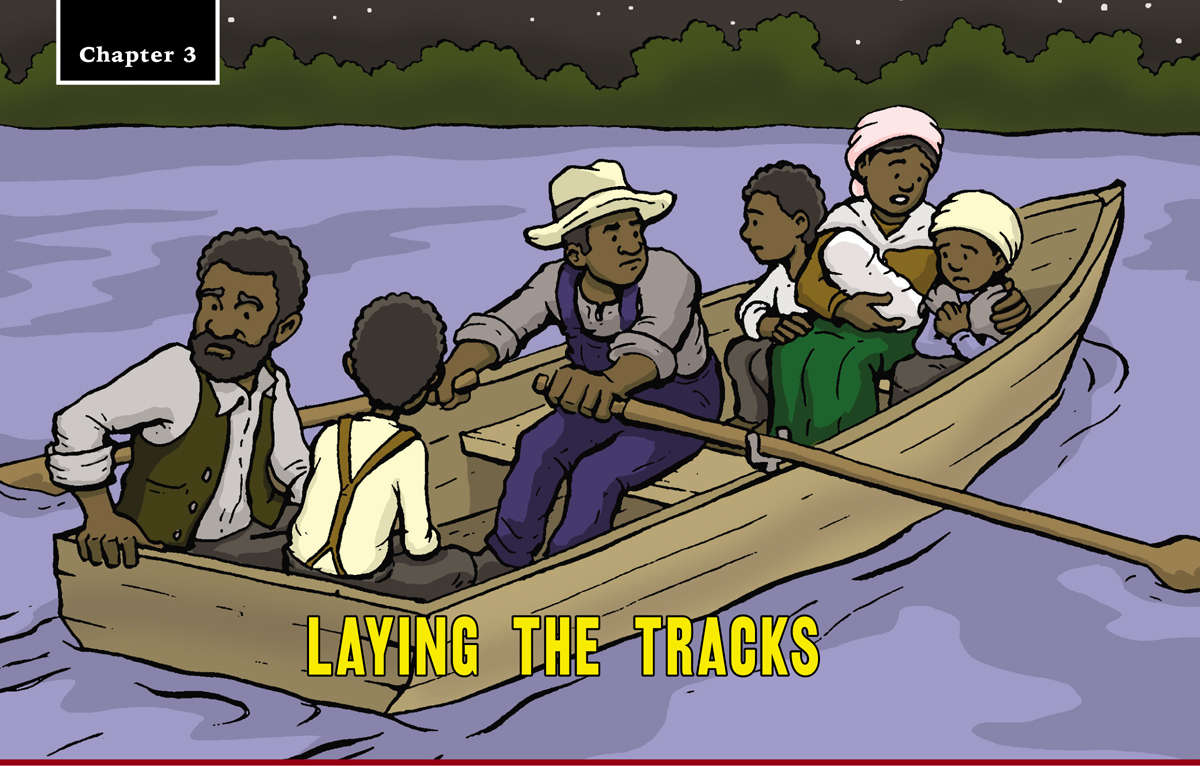

Josiah Henson stole away with his family on a dark, moonless, September night in 1830. The Riley farm was near the Ohio River, and Henson begged another slave to row the family across. As they climbed aboard the skiff, the man whispered, “You’ll not be brought back alive, will you?” “Not if I can help it,” Henson replied.

The family sat as still as death, the only sound the whisper of the oars in the water. When Henson’s feet touched the shore of Indiana, he “… began to feel that I was my own master.” But it was too early to celebrate. Although Indiana was a free state, it was full of slavery supporters. If the wrong person spotted them, the Henson family was doomed. Hiding by day, walking by night, they headed east toward Cincinnati, Ohio, 150 miles away.

skiff: a shallow, flat-bottomed, open boat.

immigrant: a person who settles in a new country.

THE FIRST TRAIN LEAVES THE STATION

Since the Underground Railroad was not a real train, no whistle blew and no conductor called, “All aboard.” Historians have had to hunt for evidence about where this undercover operation began. All clues point to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the city was the place to be for young men in search of fortune. Philadelphia was the nation’s first capital. Members of Congress strolled down the streets alongside European immigrants, Quakers in broad-brimmed hats, and free African Americans.

Slavery still existed in Pennsylvania, but it was dying out. In 1780, the state passed the first state Abolition Act. Vermont had already abolished slavery through its state constitution, in 1777. In Pennsylvania, slaves born before 1780 had to remain slaves, but those born after that date would become free on their 28th birthday. Most slave owners in Philadelphia had voluntarily freed their slaves by 1800.

Isaac Hopper (1771–1852), who was white, was only 17 years old in 1787 when he left his parents’ home in New Jersey and moved to Philadelphia. When Hopper was seven years old, an elderly servant had brought the boy to tears when he told Hopper how he had been kidnapped from his home in Africa. From then on, Hopper felt a deep sympathy for the plight of slaves.

Isaac Hopper took his Quaker faith seriously and devoted his life to helping African Americans.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Why did the Underground Railroad start when it did? Why not sooner?

unscrupulous: dishonest.

loophole: an error in a law that makes it possible for some people to legally disobey it.

collaborators: people who work together in order to achieve a goal.

document: to record.

In 1796, Hopper was elected to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Unscrupulous slave traders sometimes kidnapped free blacks and sold them into slavery. The Abolition Society gave him the job of investigating kidnapping cases and representing the African Americans in court. Hopper found every loophole within the law to help these people remain free. However, it did not take long for him to move from using the law to aid free blacks to breaking the law to help slaves escape to freedom.

Stories about Isaac Hopper and his small group of secret collaborators are the earliest documented records of the Underground Railroad. The people who worked with Hopper were from all races and economic levels. White Quaker farmers, black dock workers, and middle class shopkeepers joined forces. No single person was in charge. What united this handful of people was a moral belief that slavery was wrong.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 1796, no one used the term Underground Railroad. Trains had not even been invented!

Hopper and his colleagues worked out procedures that eventually became standard on all Underground Railroad routes. Fugitives were sent on foot, horseback, or wagon to a safe location. Disguises were used to confuse slave catchers.

Hopper even put a fugitive’s freedom before his own safety. His home near the river in Philadelphia often sheltered runaways. Once, he sneaked up the stairs of a house and grabbed a pistol from a man who was whipping a slave girl. By the time Hopper died in 1852, he had saved hundreds, possibly even thousands, of runaway slaves and established a model of resistance.

In the early nineteenth century, Quakers made up only about 2 percent of the U.S. population, less than 100,000 people. However, Quakers kept strong ties with each other. They conducted monthly and yearly meetings when families gathered from all around the country. The work of the Philadelphia activists spread to other Quaker groups, and more track was laid for the Underground Railroad.

COMMUNITY OF QUAKERS

When Levi Coffin (1798–1877) was a young man, a wagon train of westward-bound settlers passed his home in New Garden, North Carolina. A short time later, a black man appeared on the road. He asked Levi how far ahead the wagons were. Levi told him and the man trudged on.

Dismal Swamp

Some slaves escaped to remote areas that were known as maroon communities. The largest of these was located in the Great Dismal Swamp, which covers part of Virginia and North Carolina. The swamp originally covered about 1.3 million acres, most of which was below water. The dry parts were home to wild cattle, bear, wolf, deer, and fugitive slaves. Whites believed the swamp gases poisoned the air, so they usually didn’t go looking for runaways there. Today, 112,000 acres of the Dismal Swamp are preserved and archaeologists have found remains of settlements where generations of fugitives lived.

Later that day, Levi saw the man at the local blacksmith’s shop with a white man. It turned out the man was a runaway. His wife and children had been sold to a family traveling west. The slave had chased after them, but he was caught. As Levi watched, the blacksmith attached a chain around the fugitive’s neck and cuffed his wrists.

“Now you shall know what slavery is,” the owner said. He tied one end of the chain to his buggy and whipped his horses into a trot. The slave had to run to keep up with the wagon or be dragged by his neck. This incident changed Levi Coffin’s life.

When he was adult, Coffin was known for being someone fugitive slaves could turn to for help. In 1819, he and other Quakers came to the aid of a fugitive named John Dimery, the first runaway who used the Underground Railroad in North Carolina that historians can identify by name.

Dimery had been freed from slavery by his owner in another part of North Carolina. He moved to New Garden with his wife. When Dimery’s prior owner died in 1819, his sons came looking for their father’s former slave, hoping to sell him. They burst through Dimery’s door in the middle of the night and seized him. Dimery yelled for his daughter to “fetch Mister Coffin.”

Two Quakers caught up with the kidnappers at a neighbor’s house. They demanded the men either release Dimery or appear before a judge to prove their claim that he was a slave.

It was not easy being an abolitionist in a state full of pro-slavery citizens. In 1826, Levi Coffin and his wife, Catherine, moved west to Fountain City, Indiana. The couple not only packed up their clothes, furniture, and farm tools, they also brought their wish to help runaways. Before long, the Coffin home was a key safe house for three routes for fugitives.

While the kidnappers debated what to do, a woman in the house untied Dimery’s hands when no one was looking. He raced out the door, disappearing into the woods. Afraid they might be arrested, the kidnappers ran off. Decades later, Levi Coffin’s uncle recalled that Dimery “started on the Underground Railroad that night and soon landed at Richmond, Indiana.”

BLACK BUSINESSMEN TAKE THE LEAD

One of the most effective stops on the Underground Railroad is also one of the most mysterious—Madison, Indiana, 80 miles downriver from Cincinnati, Ohio. This stop was operated by a group of African Americans led by a freeborn black man named George DeBaptiste. None of the people involved in this network left written records about their activities, so historians are left with only fragments of evidence.

Madison had a population of 10,000 people in the early nineteenth century, and only 200 of them were African American. The town sat on the banks of the Ohio River. A small group of black businessmen worked together to help fugitives. George DeBaptiste ran a barbershop in the heart of town where he could listen for local gossip. John Carter, the owner of a market stall, received messages about runaways who needed help getting across the river.

bluff: a high, steep bank.

Stepney Stafford operated a laundry that was used by pro-slavery families. As the staff delivered the wash to these homes, they eavesdropped for word of slave catchers on the prowl. Elijah Anderson ran the blacksmith shop by day and conducted fugitives by night.

Two white men, John Todd and his brother, were also part of this circle of collaborators. When it was safe for a fugitive to cross the river, John beat on a brass pot and waved a lantern to his brother, who watched from the other side.

To help fugitive slaves was to put yourself in danger, especially if you were a free black.

In 1846, Kentucky slave owners and the pro-slavery citizens of Madison launched an effort to destroy the Underground Railroad in town. White mobs invaded the homes of free blacks. A conductor named Griffin Booth was almost drowned in the Ohio River. Elijah Anderson moved to another town and George DeBaptiste fled to Detroit, Michigan. However, other people filled their places and runaways could still find help from the black community in Madison.

Horse for Sale

When a fugitive was ready to run, an operator would send a message to George DeBaptiste in code that might read like this: “Mahogany Stallion. Large. Just the thing for a minister. Can see him on Tuesday afternoon. Price $100.”

This told DeBaptiste that the fugitive was an adult male of mixed race, that a church member would be at a certain place on Tuesday afternoon with the fugitive, and that the slave had $100 of his own money.

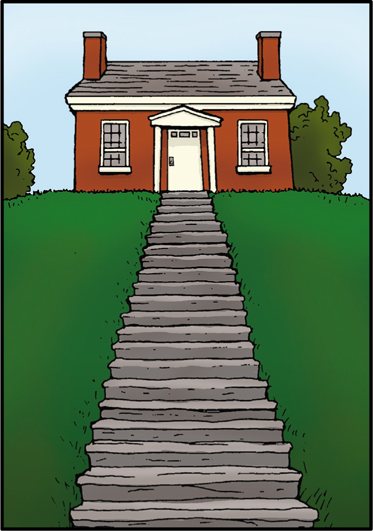

In the small town of Ripley, Ohio, a red brick farmhouse sits atop a steep bluff that overlooks the town. More than 200 steps climb from the Ohio River to the front door of the house. This house belonged to Minister John Rankin in the early nineteenth century, and it was the heart of the early Underground Railroad in Ohio. John Rankin, his wife, Jean, and their 13 children helped as many as 2,000 fugitives during the course of 30 years.

At the time, Ripley had a population of 3,000 people. The local economy was based on boat building and hog butchering.

Certain conditions made Ripley a ripe location for Underground Railroad activity.

First, there were several anti-slavery ministers in town. Also, the town was home to between 150 and 200 politically active white abolitionists. Additionally, this region of Ohio had a small population of free blacks who lived along the river and were in the perfect position to aid runaways.

The Rankin family was always on duty. The nine sons shared a bedroom, with the three oldest sleeping in one double bed. They rotated positions every night. The son on the outside of the bed had to answer the door and transport any fugitives to the next safe house on the line. The daughters prepared the food, washed and mended fugitives’ clothing, and provided medical care.

immortalize: to be remembered forever.

heroine: a woman admired for bravery.

catalyst: an event that causes a change.

segregate: to separate people based on race, religion, ethnicity, or some other category.

slum: a crowded area of a city where poor people live and buildings are in bad condition.

One of the fugitives John Rankin assisted became immortalized in literature. On a bitterly cold night in the winter of 1838, a black woman carrying an infant walked toward the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Suddenly, dogs began to bay. The woman raced to the water’s edge, a plank in one hand, her baby in the other. With her first step on the ice, the woman’s foot fell through. She yanked her leg up and ran toward the Ohio shore. Suddenly, she fell through the ice. Pushing her baby ahead of her on the ice, the fugitive levered herself up with the plank. She crept along on her belly until she finally reached the opposite shore and collapsed.

A slave catcher named Chancey Shaw watched. He had planned to grab the woman and return her for a reward. However, Shaw heard the baby whimper and something inside him thawed. He said, “Woman, you have won your freedom.”

Then he pointed to the staircase leading to the Rankin house. “No [fugitive] has ever been got back from that house.”

The fugitive eventually reached Canada. John Rankin told the story to abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe. She based the heroine of her 1852 anti-slavery novel on this fugitive, naming her Eliza.

The book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, became a bestseller around the world. It awakened Northern whites to the horrors of slavery, and angered Southern whites who thought the book was a pack of lies. This novel was one of the catalysts that started the Civil War.

URBAN UNDERGROUND

In the 1830s, Manhattan was a very smelly place. The city had a population of 300,000, and no sewage system, no housing codes, and few police officers. The air smelled of human waste, unwashed bodies, pigs, and charcoal. Men hawked fresh oysters and young girls sold hot corn. On any given day, more than 900 cargo ships lined the waterfront of the East River.

DID YOU KNOW?

The character of Uncle Tom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel was loosely based on the life of Josiah Henson.

Racism followed free blacks throughout the city. In order to vote, men had to own a certain amount of property. Because most blacks were poor, they could not vote. Schools were segregated, as were theaters, restaurants, and hotels. African Americans could only ride the horse-drawn buses if they clung to the outside of the carriage. Approximately 15,000 blacks crammed into a section of Manhattan that was dirty, poor, and crime-ridden. The “Gates of Hell” and “Brickbat Mansion” were the nicknames of slum apartment buildings.

An informal ring of thieves called the “New York Kidnapping club” prowled the city streets. This group of professional slave hunters, city police officers, and local lawyers kidnapped free blacks and sold them into slavery. A man could claim that a black person was his runaway slave simply by submitting a sworn statement to the court.

In the fall of 1835, some African Americans organized a group called the Friends of Human Rights. Their goal was to stop slave catchers from kidnapping free blacks. David Ruggles (1810–1849) led the group’s Vigilance Committee. Ruggles had grown up in the North, never witnessing slavery. But he was determined to free as many slaves as he could.

Under Ruggles’ leadership, the Vigilance Committee advertised descriptions of blacks who had been kidnapped, raised money to help fugitives, and hired lawyers to defend runaways.

Ruggles’ home became Manhattan’s main depot on the Underground Railroad. Fugitives from as far away as Philadelphia were directed to his house when they arrived in the city. He did not keep his activities a secret. One year, he rented an apartment only one block away from the busiest street in New York City.

A letter of introduction from David Ruggles helped fugitives once they left New York City. He had allies who could move fugitives farther up the East Coast and into Vermont and New Hampshire. Quaker towns and black settlements took in runaways bearing letters signed by David Ruggles. He did not live to see the end of slavery, though. Ruggles died in 1849, at the young age of 39.

The tracks of the Underground Railroad did not stay in place as real train tracks do. Because of the constant changes, runaways often had to find their own way for many miles. Navigational skills were vital if a fugitive was to survive. In the next chapter, you’ll explore the routes runaways took and how they found their way on the journey to freedom.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Now it’s time to consider and discuss the Essential Question: Why did the Underground Railroad start when it did? Why not sooner?

THUMBS UP OR THUMBS DOWN

Many Northerners loved Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Southerners were known to hate it. A person’s opinion of the book depended on whether the person was for or against slavery.

Read these two brief excerpts from reviews of the book. What words reveal which excerpt is from a Northern newspaper and which is from a Southern one?

Excerpt 1: “...It is, unquestionably, a work of genius …. It has the capital excellence of exciting the interest of the reader; this never stops or falters from the beginning to the end …. Another cause of the wide-spread popularity of Uncle Tom is its foundation in truth.”

Excerpt 2: “We have said that Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a fiction. It is a fiction throughout; a fiction in form; a fiction in its facts … and falsehood is its end ….”

EXPLORE MORE: Read a modern novel about slavery and write a review of the book. Some titles include Copper Sun by Sharon Draper, Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson, and Day of Tears by Julius Lester.

Ruggles and Douglass

In 1838, a young, escaped slave named Frederick Augustus Bailey knocked on David Ruggles’ door. Bailey was determined to flee to Canada. A week spent with Ruggles changed American history. Ruggles helped Bailey find work in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and convinced him to shed his past as a slave. Bailey changed his name to Frederick Douglass and went on to become the most influential leader for African American rights in the nineteenth century.

WORDS TO KNOW

influential: having power to make changes.

CONSTRUCT A MINIATURE DISMAL SWAMP

The Great Dismal Swamp once covered more than 1 million acres, but during the centuries, the swamp has shrunk by tens of thousands of acres due to damming and draining. In 1974, the federal government established the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge to preserve the land and species that live there.

A swamp is an area of wet, spongy ground that grows woody plants, such as trees and shrubs. Much of the swamp is a wetland. Water covers the soil or is near the surface of the soil for much of the year. Wetlands support thousands of water and land animals and absorb and slow floodwaters.

Build your own Dismal Swamp model to see the water-soaking characteristics of a swamp. You’ll need a container and materials for the land and the swamp.

Construct your landform in half of your container and lay your swamp material alongside it in the rest of your container. Make it rain by sprinkling water over your miniature world. What happens to the water?

After the rain stops, remove the swamp material and squeeze it out. How much water was absorbed by the swamp? Leave the swamp out of the container and make it rain again. Where does the water go now?

EXPLORE MORE: Wetlands act as buffers to protect houses from flooding. Create a structure to represent a building and set that on your landform. What happens to that building when it rains hard when the swamp is in place? What about when the swamp is removed?