Fear perched on Josiah Henson’s shoulder throughout his journey north. The trail through the Ohio wilderness was a never-ending maze. The cries of hunger from his children were blows to Josiah’s heart, and the threat of capture haunted his every step. Josiah recalled, “A fearful dread of detection ever pursued me, and I would start out of my sleep in terror, my heart beating against my ribs, and expecting to find the dogs and slave-hunters after me.”

Henson had reason to fear. As the nineteenth century progressed and the activities of the Underground Railroad increased, slave owners pressured the federal government to pass laws to protect their slave property. By 1850, both fugitives and anyone who helped them were at great risk.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Why would slaves risk the dangers of escape to gain their freedom?

Escape to a free state did not make a slave free. The Constitution guaranteed slave owners the right to take back their escaped slaves. The 1793 Fugitive Slave Act authorized the arrest of runaways throughout the United States, while a free person who aided a fugitive could be fined $50. But under the 1793 law, hunting down a runaway was the slave owner’s responsibility.

A slave was considered private property and the return of an escaped slave was considered a private act. The sheriff and police department were not required to launch a search. Slaveholders had to search on their own or hire a slave catcher. As the Underground Railroad expanded and more fugitives escaped, Southerners demanded something be done to stop this loss of property.

In 1848, the United States won a war with Mexico and gained vast stretches of land in the Southwest. The debate over whether these lands should be slave or free states threatened to split the nation apart. Political leaders tried to solve the problem by passing the Great Compromise in 1850. Part of this compromise included a new, harsher fugitive slave law.

A Drop in the Bucket

It’s impossible to know exactly how many enslaved people escaped in the years before the Civil War began in 1861. Many records didn’t survive history and escaped slaves needed to keep quiet, anyway. Estimates range between 1,000 and 5,000 a year from 1830 to 1860. That means between 30,000 and 150,000 slaves escaped, which is a drop in the bucket compared with the 4 million slaves who lived in the United States in 1860.

warrant: a document issued by a court that gives the police the power to do something, such as search a building or arrest a person.

incentive: something that encourages someone to do something.

commissioner: an official in charge of a government department.

verdict: a legal decision made by a judge or jury.

appeal: a legal procedure in which a case is brought before a higher court in order for it to review the decision made by a lower court.

freelance: a person who hires out his services independently without working under the control of one boss.

flog: to beat or whip someone.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law stacked the dice against black people, both free and enslaved. The private responsibility of a slave owner to find his runaway slave was transformed into the government’s job. An owner could get a warrant and demand assistance from federal court commissioners to find and arrest suspected fugitives. The commissioners relied on a general description of the escaped slave, such as gender, skin tone, age, and scars to identify the slaves they were searching for.

When a free African American matched the vague description of a fugitive, he was often arrested. Do you think this was fair?

The Fugitive Slave Law had a built-in incentive for commissioners to ignore cases of mistaken identity. They were paid $10 for every fugitive returned to an owner, but only $5 for ruling that the arrested person was not the runaway. Free blacks faced the real threat of being enslaved. When someone was arrested on suspicion of being a fugitive, he or she did not get a jury trial. Instead, the case was heard before a judge whose verdict could not be appealed. The Fugitive Slave Law sent free blacks fleeing to Canada in droves.

DID YOU KNOW?

Instead of derailing the Underground Railroad, more tracks were laid, more agents became active, and more enslaved people escaped from slavery.

Life had suddenly become far too dangerous in the United States for anyone with dark skin.

SLAVE WATCHERS AND SLAVE HUNTERS

John Capeheart was a police officer in Norfolk, Virginia, in the 1850s. He also worked as a freelance slave hunter. One of Capeheart’s tasks was to arrest all blacks who gathered in groups at night. These people did not need to be doing anything wrong. To be black and gathered in a group of more than two or three people was a crime in many states at this time.

Capeheart did not need warrants. He earned 50 cents for every black person he arrested. They would spend the night in jail, and the next morning Capeheart would take them to the mayor who assigned punishment. Capeheart carried out the sentence—flogging. He was paid an additional 50 cents for every person he whipped.

John Capeheart was part of the system Southern states used to terrorize blacks, prevent escapes, and make the capture of runaways easier. In port cities, black travelers and workers were immediately arrested if they did not carry papers proving they were free or had permission to travel. Steamboats were searched for stowaways.

patroller: a person who walks around an area to make sure rules are being obeyed.

Communities also had patrollers, sometimes called paddy rollers. These squads had legal authority to monitor the movements of black people, slave or free. Patrollers could come to anyone’s property and search any buildings without a warrant. They could shoot any black person who did not surrender on command. All Southern states had laws that prevented blacks from testifying in court against whites, so patrollers could terrorize black families without fear of punishment.

Slave catchers presented the greatest danger to runaways. Unlike patrollers, who were local farmers, the slave catchers were professional human hunters who used dogs to track a runaway’s scent.

Mary Reynolds grew up a slave in Louisiana. She recalled going to a prayer meeting in the woods one night with her parents and sister, a prohibited activity. When the family was returning to the plantation, Mary heard the dogs baying and the sound of horse hooves on the road. She said, “Maw, its them … hounds and they’ll eat us up.” Her mother and father told Mary and her sister to stand alongside a fence post and not move. The parents ran into the woods to distract the patrollers.

Mary and her sister stood there, “holdin’ hands, shakin’ so we can hardly stand. We hears the hounds come nearer, but we don’t move. They goes after paw and maw …” Luckily, her parents made it inside their cabin before the dogs reached them, and Mary and her sister made it home safely, too.

Sometimes, if not stopped by their owner, dog packs would tear a fugitive to pieces. This is part of the poem, “The Gospel of Slavery: A Primer of Freedom,” printed in 1864. Who is the beast according to this poem?

B Stands for Bloodhound

On merciless fangs

The Slaveholder feels that his “property” hangs

And the dog and the master are hot on the track,

To torture or bring the black fugitive back.

The weak has but fled from the hand of the strong,

Asserting the right and resisting the wrong,

While he who exults in a skin that is white,

A Bloodhound employs in asserting his might.

—O chivalry-layman and dogmatist-priest,

Say, which is the monster—the man or the beast?

DISGUISE AND DECEPTION

While the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made it harder to escape slavery, fugitives and their allies on the Underground Railroad changed their tactics to better avoid capture. Conductors and runaways became masters of disguise. They invented many methods of escape and built hard-to-find hiding places. When these strategies failed, fugitives fought back, taking their freedom by force.

Hiding in plain sight was the way William and Ellen Craft escaped slavery in the Deep South. In 1848, Ellen, a fair-skinned woman, disguised herself as an injured, rich male planter who was headed north for medical treatment.

illiterate: being unable to read or write.

She bandaged her face to muffle her voice and kept her right arm in a sling so she would not be expected to sign anything. The sling was a critical part of the disguise because Ellen was illiterate, and a rich man from the planting elite would certainly know how to write. Ellen’s husband, William, pretended to be her slave. The couple traveled all the way from Georgia to Massachusetts and no one questioned their disguise.

SAFE SIGNS

Fugitives often had to make their own way from station to station. Conductors sometimes used signals to communicate. Harriet Tubman used the hoot of an owl and John Rankin left a lantern burning in his window to show that his house was a refuge. Runaways always had to be careful of whom they trusted.

Slave catchers sometimes hired free blacks to pose as fugitives in order to trap an Underground Railroad agent. Therefore, when a conductor or fugitive knocked on the door of a safe house, the stationmaster used a code to determine if the runaway was really who he claimed to be. When the stationmaster asked, “Who is it?” the conductor replied, “The friend of a friend.”

Arnold Gragston, an enslaved man who lived on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, used a code phrase in his work helping slaves. Gragston’s owner let him move about without a lot of restriction. He worked for four years helping fugitive slaves cross the river to John Rankin’s house.

Three or four times a month, on moonless nights, Gragston arranged to meet fugitives on the Kentucky shore. He would ask a single question: “What you say?” Out of the darkness would come the one-word reply: “Menare.” This password proved that these fugitives were legitimate and not a trap. Menare is the Italian word for “lead.”

This was what agents on the Underground Railroad had pledged their lives to do—lead people to freedom.

One night in 1863, someone spotted him at work, and Gragston rowed across the river for the last time to escape the consequences. Arnold Gragston lived out the rest of his life as a free man in Detroit.

SAFE PLACES

Boxes, barrels, wagon beds, and crawl spaces—these were some of the places fugitive slaves hid themselves. The more ingenuous the hiding spot, the more likely the runaway could avoid detection.

In 1849, Samuel Smith packed his friend Henry Brown into a box. Brown weighed 200 pounds and was 5 feet, 8 inches tall. The box was 3 feet long, 2 feet wide, and just over 2 feet deep. Smith drilled three air holes in the box, addressed it to the Philadelphia Antislavery Society, and delivered Brown to the railway express office in Richmond, Virginia.

After traveling for 27 hours by wagon, train, and steamer, Brown was delivered to Underground Railroad agents who waited for him at the Antislavery Society office. As one man pried open the box, several others watched, afraid they would find a corpse.

Instead, Brown stood up on shaky legs, extended his hand, and said, “How do you do, gentlemen?” What physical challenges would Brown have encountered during the hours he spent in the box? What emotional challenges?

Brown was not the only enslaved person to use extreme measures to reach freedom. In 1835, Harriet Jacobs ran from her sexually abusive master.

The resurrection of Henry Brown at Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

However, she had only the help of a couple relatives, not the Underground Railroad.

Unable to find a safe way out of Edenton, North Carolina, Jacobs hid in a crawl space in her grandmother’s cabin. At its peak, the space was only 4 feet high. Mice ran over Harriet’s bed at night. When it rained, water leaked in and soaked her bed and clothes. Harriet Jacobs spent seven years in that crawl space before a friend found a ship captain willing to take her to Philadelphia. The length of Harriet’s stay shows how difficult it was for slaves to escape when they did not have the assistance of Underground Railroad agents. What else does it show?

The entire community of Oberlin, Ohio, was a station on the Underground Railroad. Oberlin College was founded in 1833, and two years later, the school took a radical step—it began admitting nonwhite students. That same year, the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society was formed, dedicated to the immediate emancipation of slaves.

The Underground Railroad Goes Underground

One of the only places where the Underground Railroad was actually underground can be seen at the Milton House Museum in southern Wisconsin. The house was built in 1844 by Joseph Goodrich to serve as a stagecoach inn. Goodrich was an abolitionist, and when he built the inn, he also constructed a 44-foot tunnel that led from the inn’s cellar to a log cabin behind the house. Fugitive slaves hid in the cellar and used the tunnel to leave the inn quickly when necessary.

stronghold: an area where most people have the same beliefs and values.

conscience: a person’s beliefs about what is morally right.

By the late 1850s, the town had a black population of 344 people, including 28 fugitive slaves. African Americans worked as saddle makers, masons, and carpenters. They farmed, ran businesses, and attended the college.

Many of these individuals knew the horror of slavery from personal experience, and they worked alongside white abolitionists to shelter fugitives.

The 1858 kidnapping of John Price reveals how the network operated in Oberlin. Price escaped from slavery in Kentucky in the mid-1850s. He had been living in Oberlin for two years when slave catchers arrived in 1858. The two hunters, Anderson Jennings and Richard Mitchell, knew the town was an abolitionist stronghold, so they wanted to nab Price quickly and quietly.

The pair conspired with pro-slavery locals to lure Price out of town with the promise of work. Mitchell, accompanied by a federal marshal, weapons, and a warrant, forced Price into a carriage and drove him to the nearby town of Wellington to catch the southbound train to Kentucky.

DID YOU KNOW?

The abolitionist town of Oberlin, Ohio, had a black lawyer named John Mercer Langston.

News of the kidnapping spread through Oberlin. White and black citizens raced to Wellington. Soon, almost 500 men crowded the street in front of the hotel where Price was being held. They shouted at the slave catchers to release him, claiming the kidnapping was illegal. Just then, the train rolled into town.

Price escaped in the chaos. The crowd paraded back to Oberlin in jubilation and held a bonfire in the town square. Price was sheltered in the home of an Oberlin professor until it was safe enough to move him out of town. Eventually, the man reached Canada and freedom.

Prosecutors pressed charges against some of the men who had been present when Price escaped from the hotel. During the trial, defense lawyers claimed the defendants were following a law that was “higher” than the Fugitive Slave Law—their conscience.

Eventually, Simeon Bushnell and Charles Langston were convicted. Langston boldly addressed the court, saying every man “had a right to his liberty under the laws of God.”

Bushnell received a 60-day jail sentence, but the judge was so moved by Langston’s words that he gave him only 20 days in jail—far shorter than the six months allowed by the law.

FIGHTING BACK

Some Underground Railroad agents used force to protect fugitives. On September 11, 1851, in Christiana, Pennsylvania, a battle broke out between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces that Frederick Douglass labeled “Freedom’s Battle.”

posse: a group gathered together by the sheriff to pursue a criminal.

Three Maryland slaves escaped from owner Edward Gorsuch and sought shelter in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. An informant told Gorsuch where he could find the men. Gorsuch got the necessary warrants from Philadelphia officials and rounded up a posse that included federal marshal Henry Kline.

A “Special Secret Committee” in Philadelphia had been trailing Kline. They sent word to the black population of Lancaster that slave catchers were on the way. The fugitives were hiding in the house of John Parker, who had weapons and was ready to fight.

DID YOU KNOW?

John Parker was a fugitive who had escaped slavery in 1839.

Henry Kline and Edward Gorsuch barged into the house at dawn on September 11. They were met by Parker and the other fugitives, plus a crowd of friends and neighbors, all of whom attacked Kline and Gorsuch with rifles, clubs, and scythes. Gorsuch was killed and Kline fled. Afterward, the fugitives and the Parker family fled to Canada. Although the federal government charged some members of the crowd with treason and murder, a jury found them innocent on all counts.

A HIGH PRICE

Not all runaways escaped. Those who were recaptured paid a terrible price. Whites who aided runaways could be fined or jailed, but owners took blood and flesh from their slaves as punishment.

Most owners believed physical pain discouraged future escape attempts. Fugitives were whipped, paddled, beaten, branded, and sometimes had their ears sliced off. If the slave was considered likely to run again, he was usually sold to a plantation in the Deep South.

As a teenager, Moses Roper was determined to escape his owner, John Gooch. Gooch was just as determined to break Roper’s spirit. After one failed attempt to flee, Gooch lashed Roper 500 times on his bare back and chained him in a pen where he lay all night on a dirt floor. The next morning, Gooch tied Roper to a heavy plow, forcing him to drag it to the cotton field like an ox.

After another escape attempt, Gooch bent 20-pound iron bars around Roper’s feet and hung him from his wrists. A third escape resulted in Gooch putting Roper’s hand in a vice and squeezing until all Roper’s fingernails peeled off. Then Gooch beat off Roper’s toenails with a hammer. Still, Roper tried to run, so Gooch eventually sold him.

Moses Roper finally escaped from slavery in 1835 and moved to England.

A bold and desperate courage was required to attempt escape. Slavery was brutal, so it makes sense that enslaved people would risk everything to run. But what motivated agents on the Underground Railroad to take the chances they did? In the next chapter, you will meet conductors and stationmasters, some famous and others unknown. These men and women shared one trait—they were willing to sacrifice their lives and livelihoods for the human rights of others.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Now it’s time to consider and discuss the Essential Question:

Why would slaves risk the dangers of escape to gain their freedom?

ADVERTISEMENT TRANSFORMATION

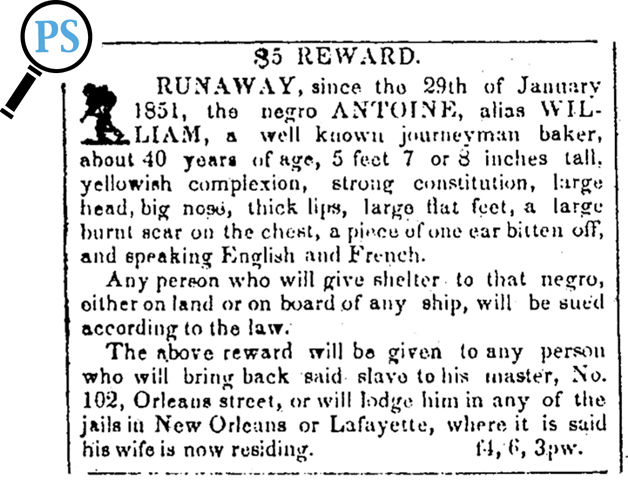

When enslaved people ran away, owners posted notices in the newspapers and on broadsides. Sometimes, the qualities that an owner described as negative in the advertisement were actually strengths that could help the fugitive.

(The Louisiana Courier, February 4, 1851)

Analyze the advertisement, above, posted in 1851 for a runaway slave.

What does this ad tell you about the appearance, character, and skills of this fugitive slave? How might these characteristics hurt the slave’s ability to avoid recapture? How might these characteristics help the slave remain free? What does this ad reveal about the kind of person who placed the ad?

Rewrite this ad to make it positive. Imagine the owner is writing a letter to recommend this slave for a job. How can you turn the qualities that the writer identifies as flaws into strengths?

People involved in the Underground Railroad were technically criminals. They broke federal and state laws. They justified their actions because they believed slavery was evil, so any law that supported slavery was also evil. Refusing to obey a law that you believe is morally wrong is called civil disobedience. American history is full of examples of times when civil disobedience led to social change.

Read each of the following examples of students who engaged in civil disobedience and were punished by their school districts. Whose actions do you agree with in each scenario—the students’ or the school administrators’?

*The United States is fighting in World War II. Some students who are Jehovah’s Witnesses refuse to salute the flag and recite the “Pledge of Allegiance” because it violates their religious belief. The school expels the students.

*The United States is engaged in the Vietnam War. Some students come to school wearing black armbands to show their opposition to the war. The school district has a policy that bans such armbands because they “disrupt the educational environment.” The children are suspended from school.

*There is a protest march through town on a school day by a group protesting government cuts to educational programs. A group of students skips class to attend the march. The school district gives the students unexcused absences.

*Hundreds of high school students walk out of school in protest after the school board decides to eliminate the teaching of civil disobedience from the history curriculum because it fosters a negative image of the United States. Students are given unexcused absences for the time they miss school.

EXPLORE MORE: Most of these cases were appealed and traveled through the judicial system. Research civil disobedience in American schools to see if you can find any of the final verdicts.

WORDS TO KNOW

justify: to prove or show evidence that something is right.

civil disobedience: nonviolent protest, refusing to obey a law because it violates one’s moral beliefs.

In 1825, Captain John Anderson bought 100 acres in Kentucky and became a peddler of flesh. He made annual trips to slave auctions in Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana, and bought slaves from local farmers. This was a profitable business. From 1832 to 1834, Anderson made $50,000. Today, that is equivalent to $1.25 million. Below is a letter Anderson wrote in 1832.

Letter from John Anderson:

November 24, 1832

Dear Friend,

May next there should not be any more negroes brought to the state for sale and I think in the spring they will be brisk. Negroe men is worth in market at this time from five hundred and fifty to $650 and field women from $400 to $425. I have sold 13 and had 3 to dye with collera, 2 men that cost $900 one child worth $100. The 16 cost $5955 and the 13 I sold brought me $7640 ….

I want you to find out and purchaise all the negroes you can of a sertain description: men and boys from 12 to 25 years old and girls from 12 to 20 and noe children. Don’t give more than $400 to $450 for men from 17 to 25 years, sound in body and mine, and likely boys from $250 to $350, girls from 15 to 20 $300-$325 and yonger ….

Yours,

John W. Anderson

When Anderson died, he owned 16 male slaves and 16 female slaves. Use the information in Anderson’s letter to complete the following math problems.

*What was the average price for adult male slaves? What was the average price of field women?

*Assume that Anderson paid $300 for each male slave. If he sold them at the average price you figured out, what is the net profit that Anderson made on his male slaves?

*Assume that Anderson paid $200 for each female slave. If he sold them at the average price you figured out, what is the net profit that Anderson made on his female slaves?

*How much money did Anderson lose at the death of the three slaves he mentions in the first paragraph of his letter?

*Calculate Anderson’s net profits made on all his slaves. (Don’t forget to factor in the loss of the three slaves.)

conversion rate: a number used to calculate what value money from an earlier time in history has in today’s economy.

EXPLORE MORE: The value of the dollar in 1834 is not the same as the value of the dollar today. Inflation has caused the prices of things to increase over time. Take the number you calculated of Anderson’s net profits and multiply it by a conversion rate of 25. This is roughly how much money Anderson made in modern dollars. Would you consider Anderson to have been a wealthy man? Why or why not?