After trekking through the wilderness, Josiah Henson and his family emerged on a flat, open plain. Before them sat the town of Sandusky, Ohio, perched on the edge of Lake Erie. Canada lay on the distant shore.

A group of men were moving back and forth between a building and the lakeshore. After hiding his family behind some bushes, Josiah approached the men. They hired him on the spot to help load cargo on ships. As Josiah worked alongside another African American man, he asked for information about how to get to Canada. The man, realizing Josiah was a runaway, introduced him to the captain, who offered to take him to Buffalo, New York, where the ship was headed.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Why did people help runaway slaves if it was so dangerous?

trek: to walk for a long distance.

schooner: a sailing ship with two masts.

The captain said it was too dangerous to load the Hensons on the schooner in daylight. Slave hunters watched the docks. The captain offered to sail his ship to a nearby island, weigh anchor, and send a boat back for the Hensons when night fell.

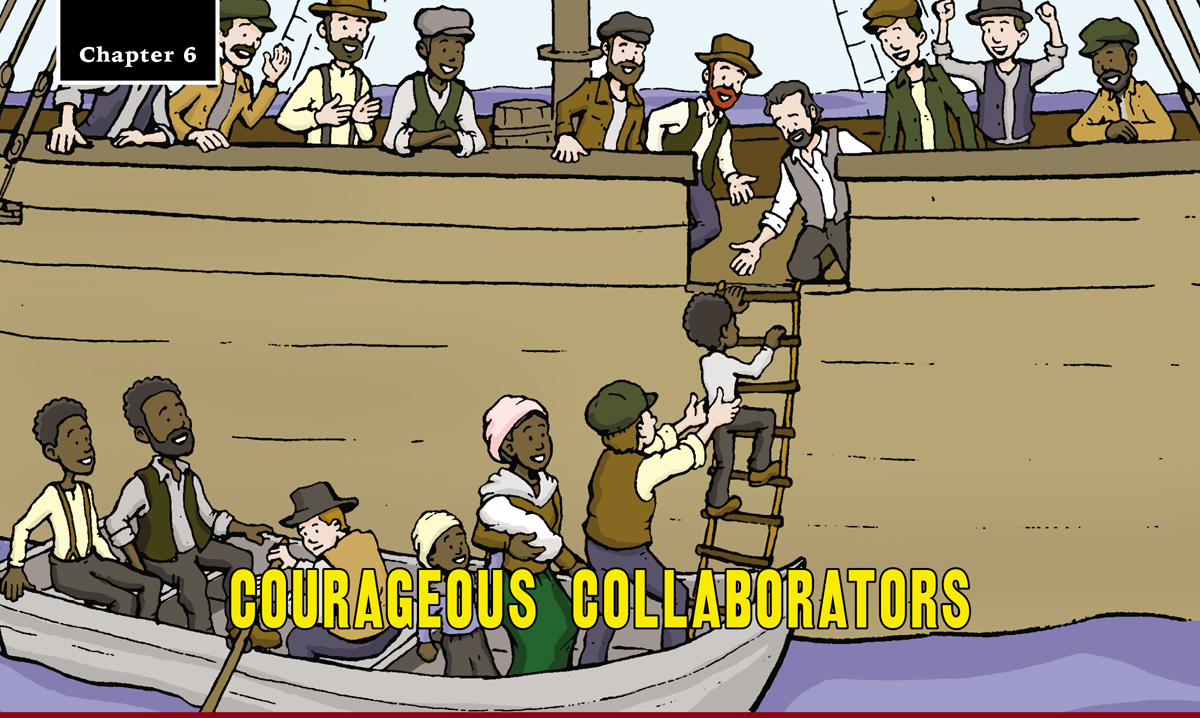

That evening, the family waited in hiding as the ship sailed away. Suddenly, the schooner swung around, sails flapping in the wind, and a small boat was lowered into the water from the side of the ship. Ten minutes later, the boat reached the shore. Three sailors jumped out to help the Hensons board, and then quickly and quietly they rowed the boat out to meet the schooner. Josiah recalled that when his family finally climbed aboard the schooner, they were greeted with “three hearty cheers.”

Josiah Henson did not make his journey to freedom alone. Allies along the way assisted him. Some, such as the Native Americans he encountered in the wilderness, were just kind strangers. But others were agents of the Underground Railroad, committed to the cause of freedom.

DID YOU KNOW?

By 1860, the dollar value of the American slaves was worth more than all America’s banks, railroads, and manufacturing businesses combined.

CONDUCTORS

Most of the Underground Railroad operated above the Mason-Dixon Line. This boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland marked the line between slave states and free states. Fugitives were largely on their own until they reached this border or the Ohio River. However, a handful of brave conductors traveled into the South to lead slaves to freedom.

hallucination: seeing, hearing, or smelling something that seems real but is usually caused by illness or a drug.

expedition: a journey with a specific purpose.

Harriet Tubman was a tiny woman with a core of steel. Her childhood as a slave on a Maryland plantation was brutal. She never got enough to eat and sometimes had to fight the hogs for their mash.

The fear of being sold away from her parents and eight siblings was constant.

When Tubman was a teenager, an event changed her life, physically and spiritually. Tubman and the plantation cook had gone to a local store one evening to buy goods for the house. A slave owned by another plantation had left work without permission and was also at the store. His overseer found him and was enraged. The overseer picked up a 2-pound weight from the counter and threw it at the slave. His aim was off. The weight hit Tubman so hard it broke her skull and drove a piece of her shawl into her head.

Tubman recovered slowly, but not completely. For the rest of her life, she suffered from episodes where she would suddenly fall asleep without warning. She also experienced visions, often seeing bright lights and hearing music or screaming.

Today, historians believe Tubman suffered brain damage from the blow to her head. But she was a deeply religious woman and she interpreted these hallucinations as messages from God.

In 1849, Tubman discovered she was about to be sold, so she decided to run. She dared not tell her mother her plans. Some of Tubman’s siblings had already been sold and her mother’s “cries and groans” at the loss of another child could give Tubman away. That night, Tubman made her escape.

Tubman traveled by night, guided by the North Star, and eventually reached Pennsylvania. She was overjoyed, but also lonely. “I was free, but there was no one to welcome me to this land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.”

For the next decade, she worked as a maid and cook in Philadelphia, saving every cent to fund expeditions back to Maryland. In December 1854, Tubman slipped into the state to rescue three of her brothers scheduled to be sold at auction the day after Christmas. On Christmas morning, Tubman, her three brothers, and three other slaves hunkered in the corncrib outside their parents’ cabin waiting for darkness so they could flee.

Tubman had not seen her mother for five years. Now, through the chinks in the corncrib walls, she watched her mother step out of her cabin, look down the empty road, and sigh. She was expecting her sons for Christmas dinner. They would never show up.

Myth Buster: Reward Offered

There is a myth that Southerners were so enraged about the number of slaves Harriet Tubman helped escape they put a $40,000 reward on her. This is false. Only several years after Tubman began rescuing family members did slave holders along the East Coast realize that someone must be aiding them. However, they never suspected Tubman.

compile: to organize together into a single publication.

poverty: to be poor.

plague: to cause serious problems or irritation.

Harriet Tubman refused to leave any loved one in bondage. She made 13 trips south and guided between 70 to 80 slaves to freedom, including her elderly parents. She helped another 50 people by providing directions on how to escape. Tubman was called “Moses,” after the figure in the Bible who led the Hebrew people out of slavery in Egypt.

Tubman conducted her rescue missions in the winter because the nights were longer and darkness cloaked the fugitives. She met runaways in cemeteries because it was natural for slaves to gather in groups in such a place. She often disguised herself as an elderly man or woman.

DID YOU KNOW?

Harriet Tubman often carried a book, even though she was illiterate. The book was part of her costume.

She died at age 91, a free woman surrounded by friends and family she had helped free. There were other conductors who traveled into slave states and met a more tragic fate.

William Still: Record Keeper

William Still: Record Keeper

William Still was born free in New Jersey and moved to Philadelphia as an adult. Ambitious and hardworking, he was hired as a clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1847. By night, he aided fugitives, about 15 each month. He interviewed everyone who came to him, refusing to allow the fugitives’ stories to disappear into the dust of history. Still said, “The heroism and desperate struggle that many of our people had to endure should be kept green in the memory ….” Following the Civil War, Still compiled these interviews into a book. The Underground Railroad: The Record is the most complete, detailed account of this secret network. You can read it at this website.

deila Dickinson William still text

Seth Concklin grew up in poverty in New York. His own struggles made him sympathetic to other people’s misery. One day, Concklin read an interview written by William Still, a free black man who worked for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and directed the city’s Vigilance Committee. Still had interviewed a former slave named Peter Friedman. When Friedman was six, he was sold away from his parents and siblings. It took him 40 years, but he managed to save up $500 to buy his freedom. However, Friedman could not afford to purchase his wife and three children.

Leaving them in Alabama, he came to Philadelphia to raise the money to buy his family. During the course of their interview, Still realized that Peter Friedman was his long-lost brother. Their mother had escaped from slavery years earlier and married a free man. That man was William Still’s father.

Concklin was deeply moved by Peter Friedman’s story and volunteered to rescue his family.

It was an effort plagued with risk. Alabama was in the Deep South, far from any Underground Railroad connections, but Concklin made the trip safely and found Friedman’s wife and children. His plan was to bring the fugitives north by steamboat disguised as a master and his slaves. However, the steamboat was late and Conklin’s plans fell apart.

Afraid to wait at the dock any longer, Concklin purchased a skiff and rowed upriver for seven days and seven nights. They made it as far as Vincennes, Indiana, before someone questioned why Concklin was traveling with the blacks. Terrified, the fugitives and Concklin provided different stories. The fugitive slaves were jailed, but Concklin was not. He could have escaped with his life, but he went to the jail to help the Friedmans. This was a tragic mistake.

The Friedmans were returned to slavery, and Seth Concklin’s dead body was found the next day washed up on the bank of the river.

Conductors who operated in free states also faced risks, especially those working along the border with the South. John Parker was born a slave. After many failed efforts to flee, he saved enough money to buy his freedom and he moved to Ripley, Ohio. Parker was a successful iron forger and entrepreneur, and at night he conducted fugitives across the Ohio River.

DID YOU KNOW?

John Parker made his first attempt to escape at age 10.

One night, Parker received word that a group of fugitives from central Kentucky was hiding in the woods about 20 miles from the river. Parker put a pair of pistols in his pockets and a knife in his belt and volunteered to aid the runaways. His collaborators in Ripley promised to have a boat waiting to pick the group up after nightfall.

Parker found eight male and two female fugitives deep in the Kentucky woods. The forest was so thick that the group could travel by day without detection. As a result, they reached the Ohio River at dusk. No boat was waiting for them because they had arrived before the appointed time.

Suddenly, the howl of dogs cut through the air. Slave catchers were close. Parker raced along the river’s edge, hoping someone had left a vessel in the weeds. He was in luck. A small skiff lay in the tall grass. But if 11 people tried to cram into the boat, it would sink. Parker had no choice but to abandon two men on the shore. One of the women in the boat began to cry. Her husband was being left behind. Without a word, a single man on the boat climbed out, giving his spot to the husband.

As Parker’s boat neared the Ohio shore, he heard shouts and saw lights where the two fugitives had been standing. Parker understood what this meant. “… The poor fellow[s] had been captured in sight of the promised land.” He’d had to make a split-second decision about who he could bring to freedom and who he must leave behind.

The strain on conductors was so great that few conductors could work more than a decade before their nerves gave out.

STATIONMASTERS

After a conductor led fugitives to a station on the Underground Railroad, the stationmaster took over. Stationmasters were in charge of feeding, clothing, sheltering, and protecting the runaways until they were moved down the line. Fugitives might stay at a station for a couple of hours or a couple of weeks.

oppression: an unjust or cruel use of authority and power.

Detroit was a major gateway to Canada. A collection of free blacks served as stationmasters for this critical depot. The Colored Vigilant Committee worked to improve the status of free blacks in the city. They fought for better schools, the right to vote, and the abolition of slavery. Many members of this committee were also active in the city’s Underground Railroad.

William Lambert (1817–1890) coordinated many of the Underground Railroad operations in the city. Born free in New Jersey, he moved to Detroit as a young man, opened a tailor shop, and became wealthy.

Lambert used his money to finance rescue efforts for those escaping slavery.

Lambert founded a secret society called the African American Mysteries Order of the Men of Oppression. George DeBaptiste, who had worked as part of the Underground Railroad in Indiana before moving to Michigan, was another member of this group. These men, almost all African Americans, worked to shelter and transport slaves escaping across the Detroit River toward freedom.

Only members of the order knew the elaborate system of secret passwords and handshakes. With this system, agents could detect traps set by slave catchers.

Stockholders

Gerrit Smith, heir to a fur-trading fortune, donated the modern equivalent of $1 billion to buy and free enslaved families. He also financed rescue efforts and funded Frederick Douglass’s abolitionist newspaper, The North Star. Smith and other rich abolitionists who donated funds to keep the network functioning were known as stockholders of the Underground Railroad.

Agents selected to travel south to rescue fugitives had to swear a solemn oath not to take anyone into their confidences unless the person was trustworthy. Those who broke this oath were considered traitors. It is unknown how many slaves were helped by this order, but certainly there were many.

WOMEN’S WORK

Women did much of the work that kept the Underground Railroad running smoothly. When runaways arrived at the home of Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, or Levi Coffin in Cincinnati,

Ohio, it was their wives, Anna Douglass and Catherine Coffin, who made up the beds and cooked the food.

Women sewed quilts and clothing for fugitives, nursed them when they were ill, and tended to their frightened children. They circulated anti-slavery petitions and sold homemade pies and jams to raise money to fund rescue efforts. The Cleveland, Ohio, vigilance committee had only nine members, and four of them were women.

The knowledge that they were helping fugitives reach freedom inspired agents on the Underground Railroad to continue their dangerous work. In the next chapter, you will explore how former slaves worked to carve out lives as free people—some in Canada and others in the United States after the North and the South had fought a bloody civil war.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Now it’s time to consider and discuss the Essential Question:

Why did people help runaway slaves if it was so dangerous?

YOU CAN TAKE THIS HERO TO THE BANK

The Treasury Department plans to put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. She will be the first African American woman, and only the third woman, to appear on American paper money. The bills will come out in the year 2020 to mark the 100-year anniversary of all women gaining the right to vote in the United States.

Design your own $20 bill with symbols, illustrations, and words that communicate the role of Harriet Tubman in American history.

*What phrases might be included on the bill?

Research online and find images of Harriet Tubman.

*Which picture should the government use on the bill? Why?

*Are there any images that symbolize the work she did on the Underground Railroad?

EXPLORE MORE: Harriet Tubman will replace President Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. He was put on the bill in 1928, but historians are not sure why. There is little documentation about that decision made by the Treasury Department. Research President Jackson’s life. Does he deserve to keep his spot on the $20 bill or is Harriet Tubman a better model of an American hero?

One of the ways historians try to understand the past is to consider the world through the eyes of people who lived at a certain time. In this activity, you will try to create the mindset of a fugitive slave.

Go to this link to find the text of a book of fugitive interviews compiled by William Still. The second link brings you to a drawing found in another version of the book. |

|

archive William still underground railroad twenty-eight fugitives escaping |

|

Read a few of the interviews. Then study the drawing. Choose one of the fugitives illustrated. Write an interior monologue from their point of view, weaving in the information you read in the interviews. An interior monologue is a piece of writing that expresses a character’s innermost thoughts from his or her point of view.

*What is this character most afraid of? What are his or her worries?

*What gives this character hope?

*Does this character feel strong? Weak? Hopeful?

*What made you choose this character?

DID YOU KNOW?

There was no director or president in all the decades the Underground Railroad was in operation. It was a grassroots organization. The power to make decisions rested in the hands of ordinary men and women.

EXPLORE MORE: What insights can writing from the point of view of a historic person give you that traditional essay writing cannot? What are the problems of this kind of creative historical writing?

WORDS TO KNOW

grassroots: an organization made up of many ordinary people.

The Order of the Men of Oppression taught a secret handshake to runaways. According to William Lambert, “… The sign was pulling the knuckle of the right forefinger over the knuckle of the same finger of the left hand. The answer was to reverse the fingers as described.”

Are you a member of a special group, such as a club, sports team, or musical group? Create a special greeting for just group members.

If you want your membership to be secret, design a greeting that will not be obvious to an outsider. The greeting does not have to involve your hands. You could tug on an earlobe or tap your elbow or hop on one leg.

Secret Societies

There have been several documented secret societies in world history. The Freemasons, founded in 1717, is one of the oldest known groups. It was founded as a mutual aid society where members came to the assistance of other members. The Skull and Bones is a secret society formed at Yale University in 1832. Today, it seems to function mainly as a social group. The Internet makes it harder to keep the doings of any organization secret today. However, Anonymous is a loosely connected international network of activists who hack government communications and leak them to the public. If this group has a secret handshake, it is probably a digital one.

What route would you choose to travel from slavery to freedom? In this activity, you will plot your journey north.

Do some research at the library and find a map of the United States in the 1850s.

*If you were a fugitive running away from slavery in Richmond, Virginia, what would be the safest, quickest route to Montreal in Canada?

*What rivers or mountains would you have to cross?

*What cities would you travel through?

*If you could walk 15 miles a day, how many days would the journey take you?

EXPLORE MORE: What do you predict will be the most dangerous segment of your journey? How can you prepare for this? Are there other routes you can take? Other destinations to choose?

Question and Answer

William Lambert claimed that the questions and answers below were taught to every fugitive his secret order aided. Runaways were expected to be able to answer them correctly in order to get assistance.

›Q. Have you ever been on the railroad?

A. I have been a short distance.

›Q. Where did you start from?

A. The depot.

›Q. Where did you stop?

A. At a place called Safety.

›Q. Have you a brother there? I think I know him.

A. I know you now.