ON APRIL 25, 1991, Edward R. Madigan, the USDA’s freshly appointed Secretary of Agriculture, made an unexpected announcement: he was halting production of the new Food Guide Pyramid at the last minute because he feared it would be “confusing to children.”1 More testing was needed, he said, to make sure the four-tiered triangle—an idea that had been gestating in the belly of the USDA for several years—wasn’t too much for America to handle.

Maybe Madigan deserved a little slack. With less than two months of secretary experience under his belt, he had entered the scene a relative fledgling, oblivious to the extensive research and years of fine-tuning that had already gone into the pyramid’s design. In fact, despite it being one of his department’s most important ventures, Madigan only learned of the pyramid’s existence two weeks prior when he read about it in the newspaper.2

But his rationale for withdrawing the new design only sparked suspicion. On April 15, Madigan had emerged from a high-pressure meeting with the National Cattlemen’s Association, who’d expressed their disgruntlement with as much subtlety as a whack-a-mole mallet. Because the proposed pyramid banished meat and dairy to the space right below the “use sparingly” tip, the Cattlemen’s Association worried it would send a guilty-by-proximity message to the public and tank the sales of their products. The milk industry joined the complaint line soon after, with one lobbyist cutting to the chase: “We’re not happy with the way we look.”3

Even though the daily serving recommendations hadn’t changed in over a decade for any of the food groups, the pyramid’s layout made clear what earlier guidelines had not: Americans should eat less meat and dairy. To industry eyes, the design seemed to stigmatize animal foods not only by shelving them near the pyramid’s blacklisted apex, but also squeezing them into its narrowest band. It was an unfortunate slice of pyramid real estate—the equivalent of crawlspace compared to the full-floor luxury suite allotted to grains.

Fig. 1. The USDA’s original 1992 food pyramid.

Upset with the pyramid’s implicit hierarchy (and, more important, their location in it), meat and dairy producers badgered Madigan to drop the new design in favor of something less incriminating.

To add insult to injury, the New York Times had rocked the barnyard with another strike against animal products just days before the Cattlemen’s meeting. On April 10, the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM)—a non-profit group promoting veganism and animal rights—asked the USDA to swap its omnivorous food guide for one nearly devoid of meat and dairy, claiming that animal protein in any form was making Americans sick and obese.4 The Times’ report of the story sparked a flurry of enraged responses, including a letter from the American Medical Association (AMA) calling the PCRM’s advice “irresponsible and potentially dangerous.”

Still, PCRM’s vegan food guide made front-page headlines across the country—leading some nutritionists to fear that the alternative guide would overshadow the government’s more “sensible” one.5,6 The message was obvious. At a time when Fig Newtons were deemed a healthier option than anything containing saturated fat, meat and dairy producers had good reason to panic. But their raucous protests did nothing to endear them to the public. By hounding the USDA into submission, food lobbyists became known as America’s schoolyard bullies—scheming to steal our lunch money, and consequently our health.

Although Madigan insisted the pyramid’s retraction wasn’t just due to industry complaints, neither the media nor the public bought his story. Journalists accused him of “flabby leadership,” lamenting that the USDA had “saluted, bowed, curtsied, and kissed the hem of the monarchs of the meat and dairy industries.”7 Newspapers ran such unforgiving headlines as “‘Pyramid’ Topples as USDA Bows to Industry Pressure” and “USDA Casts Doubt on Its Integrity.”8,9

In her acclaimed book Food Politics, Marion Nestle—department chair of Nutrition and Food Studies at New York University, and famed sleuth of the history of American food guidelines—describes how the USDA’s own employees secretly spilled the beans. Within days of the food guide’s retraction, Malcolm Gladwell, then a reporter with the Washington Post, contacted Nestle asking for her opinion on the food guide’s sudden retraction. She wrote:

As I explained to Mr. Gladwell, the food industry had often been involved in dietary guidance, and the USDA “is in the position of being responsible to the agriculture in business. That is their job. Nutrition isn’t their job.”10

As soon as Nestle’s comments appeared in print, her office in-box exploded with anonymous internal letters from USDA employees—both hand-delivered and faxed from Washington DC hotels. It was like a page out of a spy novel: unmarked envelopes with no return address, copies of the abandoned pyramid, private department memos, and other juicy bits of pyramid memoranda landed in Nestle’s hands, all suggesting that industry pressure (rather than confused children) was the real reason the pyramid faced its abrupt yanking.11

By April 1992, a full year after the national food guide drama first unraveled, Madigan was back in the spotlight—this time to announce, somewhat bashfully, that he was approving the same pyramid he’d so overtly rejected. After sopping up $855,000 in tax dollars, hosting twenty-nine focus groups in five cities, testing 415 potential designs, and clogging media outlets with ongoing gossip about the food guide’s progress, the USDA confirmed what it had concluded the year prior: the pyramid was the most effective symbol for teaching Americans what they should be eating.12

Although Madigan didn’t see anything regrettable about leading the USDA through a giant, expensive loop of retraced footsteps, he was alone in his optimism. The chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee gave Madigan a verbal lashing, declaring that it “doesn’t matter whether USDA picks a pyramid, a bowl, or an upside-down ketchup bottle … the USDA’s delay cost nearly $1 million and the administration ended up right where they started.”13 Others questioned Madigan’s claim that the past year had been one of much hard work for the USDA, since the new food pyramid seemed nearly identical to the one that would have been released originally.14

It was true: after so much retesting, the new food guide’s main changes were subtle and cosmetic. Spaghetti noodles replaced a macaroni bowl. White chopsticks stood in for green ones. A cheese wedge acquired holes to convey its Swiss heritage. And due to complaints from Kraft Foods, which had dibs on the “eating right” slogan for its own products, the USDA also dropped “Eating Right” from the pyramid’s title and christened it the Food Guide Pyramid—a name that would soon become a household phrase.15

The image’s trivial tweaks—thirty-three in all—failed to reveal what those copious tax dollars really paid for.16 As the public saw it, the government had spent a year doing what any third grader could have accomplished with a few crayons and some slightly prodigious motor skills.

But the most noteworthy change wasn’t even visible on paper: it was the meat and dairy industries’ newfound silence. Gone were the “stigmatization” protests that had plagued national headlines in months prior. Although the extra year of research left the new and improved food guide looking more like a spot-the-difference cartoon than a legitimate revision, it had undergone enough consumer testing to prove, to food industry satisfaction, that Americans wouldn’t be boycotting their beloved meat and dairy. Burgers would still hit summertime grills. Milk would still keep morning Cheerios afloat. Tofu would, for at least a few more years, remain an ostracized relic of the hippie. Although lobbyists insisted they would’ve preferred a different design—and their approval was probably born more of exhaustion than enthusiasm—they ultimately surrendered the fight. “We can certainly live with the pyramid,” the National Milk Producers’ Federation said in a New York Times article, finally nailing shut a year’s worth of drama.17

To anyone who’d been following the saga, the pyramid’s release marked the triumph of public health over shady politics, or so it seemed. The lowfat, grain-based guidelines that threatened meat and dairy producers would surely cure America’s ails—and despite initially caving to industry demands, the USDA had taken the high road by sticking with its pyramid in the face of opposition. The new menu, with promises of cleaner arteries and smaller pant sizes, would soon sweep the nation: six to eleven daily servings of grains, three to five servings of vegetables, two to four servings of fruit, two to three servings of meat and beans, two to three servings of dairy, and as few oils and sweets as the country could manage without declaring total asceticism. It seemed the road to health was paved not only with good intentions, but also with pasta.

It didn’t take long before newspapers were rife with backlash. An article in the Shopper Report noted that consumers generally saw the pyramid as “upside down and a waste of money,” with its apex-placement of undesirable foods seeming counterintuitive and confusing.18 The foodservice publication Restaurants and Institutions claimed the pyramid had unwittingly turned some consumers into “obsessive, guilt-ridden phobics who shuttled from one ‘good’ food to another,” and who “impulse-ate or binged on non-nutritious foods” between health kicks.19

Reflecting on the one-year anniversary of the pyramid’s release, Washington Post journalist Candy Sagon didn’t pull any punches. “Think about this,” she wrote in one outspoken piece. “The Egyptians built pyramids for dead people. A year ago, the US Department of Agriculture chose a pyramid for its food guide. Is there a message here?” Disturbed by what she considered impossibly high servings for cereal products, she pondered “just how powerful the grain grower’s lobby was during the pyramid’s design phase.”20

The criticisms weren’t limited to newspaper rants, either: the pyramid also found itself lambasted in scientific journals. Some experts argued that pushing all fats into the pyramid’s “use sparingly” tip would rob the American diet of essential fatty acids.21 Others felt the pyramid’s unabashedly grainy foundation—with guidelines so vague that a Toaster Strudel seemed on par with a bowl of wild rice—would raise triglycerides, reduce “good” cholesterol, and perhaps be the kiss of death for America’s already precarious heart health.22 In a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a nonprofit vegan group correctly (if not unbiasedly) noted that the pyramid’s dairy requirement was unfair to the millions of Americans with lactose intolerance, and that alternative sources of calcium should be highlighted.23

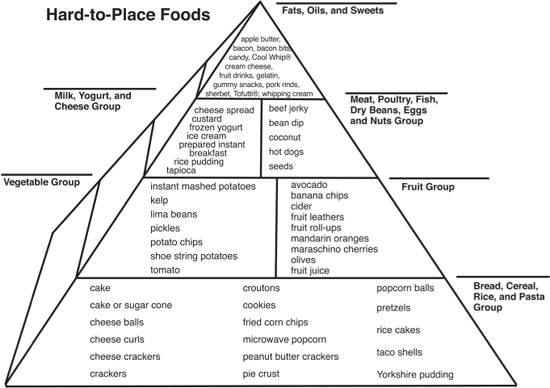

In 1994, the pyramid’s credibility took another clobbering when the Journal of the American Dietetic Association ran an article called “How to Put the Food Guide Pyramid into Practice.” Written to help dietitians convey the pyramid’s principles to their clients, the article would’ve slipped unobtrusively into the annals of history if not for one eyebrow-raising graphic: the “Hard to Place Foods” pyramid.

Fig. 3. Source: Penn state University

Originally published as part of Penn State’s Pyramid Packet, the Hard-to-Place Foods guide was supposed to help the public figure out where a variety of ambiguous items—oddities like popcorn and bean dip, for instance—fell in the Food Guide Pyramid. Unfortunately, any confusion the graphic resolved would be short lived. Cake, sugar cones, cheese curls, cookies, fried corn chips, pie crust, and Yorkshire pudding could all guiltlessly count toward a person’s six to eleven daily servings of grains. Potato chips qualified as vegetables. Custard, ice cream, and pudding would fall into the dairy group—though cream cheese, notably, was to be “used sparingly.” Overall, the graphic made the Reagan-era attempt to count ketchup as a vegetable seem downright saintly.

Not surprisingly, the article inspired a swarm of riled-up letters to the editor. One dietitian proclaimed that she would regret seeing a professional journal like that of the American Dietetic Association “referenced on a potato chip bag highlighting potato chips’ newfound membership in the vegetable group.”24 Another concerned dietitian, equally befuddled by the graphic of hard to place foods, questioned the logic behind many of the placements: “Why are corn chips in the bread, cereal, rice, and pasta group if potato chips are classified as a vegetable? … Apple butter is a fruit concentrate, so why is it placed with fats, oils, and sweets rather than with fruits? Does anyone eat enough maraschino cherries to include them as a serving of fruit?”25

Despite its food industry influences and scientific shortcomings, the USDA’s zealous marketing overpowered the naysayers. The new pyramid made itself known—and trusted—by sheer omnipresence. In the nineties, nary a cereal box could be found that didn’t boast that sacred triangle. USDA-inspired board games, posters, cookbooks, lesson plans, textbooks, and choke-free preschool bingo cards ensured the pyramid’s message reached even the youngest of Americans. Schools were required to not only preach the pyramid’s gospel in nutrition classes, but also offer cafeteria meals with enough soggy pizza and rock-hard brownie squares to meet half the pyramid’s requirements for grains.26 Like a Midas touch gone awry, the USDA pyramidized everything it came into contact with—resulting in new food stamp regulations, daycare snacks, hospital meals, and other nutrition programs that dutifully conformed to the pyramid’s instructions.

Resistance was futile. The pyramid was unstoppable. As one consumer proclaimed during a Dietary Guidelines focus group, “The food pyramid is part of the way I was trained growing up. It’s in the back of my head when I make choices.”27

Yet the graphic’s abrupt rise into the public eye—and the yearlong ballyhoo surrounding it—was neither the end of the government’s controversial role in dietary issues nor the beginning. The pyramid, in some sense, was only the tip of a much deeper brew of forces, the visible fruit of an underground alchemy. It’d been chiseled and chewed by a peculiar mix of good intentions, bad science, political meddling, and special interests—spit out only after enough compromise to render its mission useless. And the process had begun long before the pyramid’s first stone was even laid.