Sherwood Forest (Freeland Farm). Douglass lived and worked in these fields, 1835–36. Aerial view, c. 1930.

No man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake. . . . The life which he has may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks may not be gained.

—FREDERICK DOUGLASS, 1845

Douglass likely never forgot the sensation of his hands gripping Covey’s throat, his fingernails drawing blood, as he strangled the slave master. Whether it happened or not as Douglass later described it, the feeling became real in memory. By January 1, 1835, after spending the annual holiday week watching, and imbibing, with the rest of the slaves in the St. Michaels region as they frolicked, danced, and drank their days away with their masters’ approvals, Frederick Bailey was ready for more “rational” sensations.1 He was once again hired out by Auld for a year to another local farmer, William Freeland, whose land fronted on the Miles River.

As Douglass endlessly explained the nature of slavery to public audiences later in the 1840s, a major theme of his writing and speeches was the slaveholders’ mentality, their quest not only for control of the bondman’s body, but more important, “to destroy his thinking powers.” By temperament and apparently strategy, Freeland, who did not even attend church and practiced leniency about food, labor routines, and general emotional autonomy among his slaves, allowed Frederick more space and time to think, read, and, as it turned out, to clandestinely teach. Freeland did not beat his slaves; though his soil was worn-out from too much tobacco husbandry, his tools were much better than most, and he was a fair broker with his slaves’ need for rest. Frederick liked Freeland, especially in contrast to his previous year of suffering under Covey. Douglass’s mind, he recollected, gained “increased sensibility.” In Bondage and Freedom, he drew beautifully upon 1 Corinthians to say that the “natural” and “temporal” in human needs come first, and “afterward that which is spiritual.” He later mused in memoirs and speeches about how his time with Freeland taught him that when a slave gets a “good” master, it makes him only wish “to become his own master.”2

Frederick had gained a reputation in the region because of the fight with Covey; and his literacy made him a special seventeen-year-old among a mostly older group of male slaves who became his beloved “band of brothers” on Freeland’s place. Douglass “loved” (a word he sparingly used in remembering his slavery years) especially four young men: brothers Henry Harris and John Harris, Handy Caldwell, and Sandy Jenkins (the root man), now working on the same farmstead with Frederick. As Douglass set up this scene of mental liberation amid a group of trusted comrades, he delivered a clever jolt of foreshadowing. “Now for Mischief!” he declared. “I had not been long at Freeland’s before I was up to my old tricks.”3

• • •

Quickly that winter and into summer, Frederick gathered eventually more than thirty male slaves on Sundays, and sometimes even on weeknights, in a Sabbath literacy school. He may have constructed the Covey fight as his resurrection from a living death into “manhood,” but Douglass’s real manhood, his real vocation, emerged here in his leadership among a cherished group of eager learners and fellow dreamers. Here on the farm of a “just” slaveholder, in downtime from working as a field hand, the future Frederick Douglass found his first abolitionist flock. Here “in the woods, behind the barn, and in the shade of trees,” Frederick discovered his charisma and burnished his love of words. “The fact is, here I began my public speaking,” he later wrote. With The Columbian Orator in his hands, which he had somehow kept hidden from the Coveys and Aulds in his life, and with a Webster’s spelling book and a copy of the Bible, Frederick, now tall and with an adult’s deeper voice, stood before these young men and preached the power of literacy as the means to freedom. Under an old live oak on the Eastern Shore on summer Sabbaths, practicing gestures with his arms and shoulders, and modulating the sounds and cadences of his words as The Columbian Orator instructed, the greatest antislavery orator of the nineteenth century first found his voice.4 One wonders if before any of his thousands of speeches and appearances later in life, as he listened to someone drone on introducing him, or as he stepped to a lectern, a fleeting memory of his oak-tree congregations danced in his mind.

Sherwood Forest (Freeland Farm). Douglass lived and worked in these fields, 1835–36. Aerial view, c. 1930.

Douglass loved his days and nights teaching his fellow slaves. “I have had various employments during my short life,” he wrote in 1855, “but I look back to none with more satisfaction, than to that afforded by my Sunday school.” Douglass’s autobiographical writing is often extremely self-centered, drawing hard boundaries around his sole character—himself as the melodramatic self-made hero. But his remembrance of the Sabbath school is one time when he expressed an abiding love, an “attachment deep and lasting,” for his supporting cast. Frederick was the leader now of a local brotherhood, unlike anything he had known before, a gang of word lovers and emerging readers. They were “brave and . . . fine looking” as a group. He had never known other such friends in his life to the age of thirty-seven, as he rhapsodized in 1855. “No band of brothers could have been more loving.” They had secret passwords for group protection in their risky business; and what they especially possessed was a sense of a male-bonded home in their wilderness of work and hopelessness. For Frederick’s bursting spirit, “these were great days to my soul.”5

In the midst of these clandestine adventures in literacy and comradeship, Frederick and his four closest friends launched an escape plot. At the beginning of 1836, Freeland rented Frederick for yet one more year of labor. Douglass later portrayed himself as glad to stay on Freeland’s place; he could continue his teaching and building of his band of readers as he turned eighteen years old. But he also, perhaps quite honestly, remembered himself as “not only ashamed to be contented, but ashamed to seem contented.” Frederick felt a new level of despondency, the kind born of the same increased liberty to think, speak, and create the “intense desire . . . to be free” in his devoted compatriots as he had felt at a younger age in Baltimore. He left many haunting expressions of this longing in the mind of a slave reaching adulthood with an imprisoned mind. “The grim visage of slavery,” he wrote on behalf of all slaves, “can assume no smiles which can fascinate the partially enlightened slave into a forgetfulness of his bondage.”6

In a combination of providential, psychological, and even military language, Douglass told of his escape plot that nearly ended his abolitionist career before it started. “The prophecies of my childhood were still unfulfilled,” he claimed in retrospect. As he remembered Father Lawson’s words (predicting God’s purposes in Douglass’s rise in the world), Frederick believed that at eighteen he had grown “too big for my chains.” His group of five conspirators plotted their backwater rebellion like a tiny military company, with Frederick as their captain, always watching his own “deportment, lest the enemy should get the better of me.” Just before the Easter holiday in the spring of 1836, they planned to steal away into Chesapeake Bay in a large canoe owned by William Hambleton, whose large estate bordered Freeland’s farm (Douglass mistakenly calls him Hamilton in the autobiographies), rowing their way north some seventy miles to the head of the Bay, and then trekking by foot overland to the free state of Pennsylvania. Wildly ambitious and based on inadequate geographic knowledge, the plot had little hope of success, although they could visualize themselves out on the Bay claiming either to be fishermen working for their masters, or slaves allowed the holiday week off from labor. Frederick employed his literacy now to a political end for the first time—he wrote a “pass” for each member of the band, authorizing him to spend the Easter holiday in Baltimore, and signed W.H.7 These desperate young men decided to steel their nerves in group solidarity, in songs, in their secret meetings and handshakes, and in their faith in their youthful leader, who stood erect over their battlements and strove for the right words of resolve.

Their bravado, however, had to coexist with fear. Frederick and his team met by night around their quarters and on Sundays out in arbors. The eighteen-year-old played the commanding officer of the platoon preparing for war; he argued for the plan against all its admittedly logical obstacles—what he called “phantoms of trouble.” He cajoled, instilled spirit when they needed it, drew mental pictures of hope when they all felt desperation, and tried “to instill all with firmness.” But Frederick’s pep talks did not suffice. In his autobiography, Douglass later presented this episode brilliantly as a journey into the psychology of the runaway slave. Fred Bailey may have enjoyed his role as the band’s leader by words and personality, but he shared their sense of psychological terror about betrayal and capture.8

As they “rehearsed” for their fateful day of flight out of “Egypt,” Douglass remembered, they could preen and swagger for one another one moment, and the next, the Harris brothers might just stare in silent dread into Frederick’s eyes, awaiting his next direction. “We were confident, bold and determined at times,” wrote Douglass; “and, again, doubting, timid and wavering; whistling like the boy in the graveyard, to keep away the spirits.” When they sang to steady their nerves, a favorite hymn rang out:

O Canaan, sweet Canaan.

I am bound for the land of Canaan,

I thought I heard them say,

There were lions in the way,

I don’t expect to stay

Much longer here.

Run to Jesus—shun the danger—

I don’t expect to stay

Much longer here.

Douglass hastened to point out that for his band of runaways, it was not heaven they sought just then; “the north was our Canaan.”9

But what about those lions? They could not sing them away. Nine years later, Douglass left a probing statement of the recurring dream/nightmare of the runaway slave, as though he wanted to tear apart the romance of the Underground Railroad and replace it with a vision of the fugitive slave’s real psychic hell. “At every gate through which we were to pass,” he wrote on behalf of his comrades and every other bold runaway, “we saw a watchman—at every ferry a guard—on every bridge a sentinel—and in every wood a patrol.” The options faced by the runaway came from deep in historical time, from the ancient circumstance of the oppressed choosing life or death against the overwhelming weapons of the powerful. “On the one hand, there stood slavery, a stern reality, glaring frightfully upon us,” wrote Douglass as dramatist of the macabre, “its robes already crimsoned with the blood of millions, and even now feasting itself greedily upon our own flesh. On the other hand, away back in the dim distance, under the flickering light of the north star, behind some craggy hill or snow-covered mountain, stood a doubtful freedom—half frozen—beckoning us to come and share its hospitality.” Why tempt such a “monster” infesting their thoughts? On every side, they saw “grim death” in “horrid shapes.” They saw themselves drowned in the ocean, their bodies torn by bloodhounds. After thus characterizing the mind of the fugitive slave, Douglass went to Shakespeare’s Hamlet and allowed his comrades the moment to “rather bear those ills we had, than to fly to others, that we knew not of.” But they could still somehow see that distant hill. Then Douglass invoked Patrick Henry’s famous “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech from the American Revolution and claimed that the American slave rebel’s right to this bold resolution was “more sublime” than any by one of the founding fathers. The “lash and chain” had bought that privilege.10

So, brave but terrified, Frederick and his small band awoke on their prospective day of deliverance, Saturday, April 2, 1836. They had packed little bags and gone to the field to do their early-morning work—spreading manure. Their plot fell into disaster almost immediately. They had been betrayed (Douglass later thought probably by Sandy Jenkins, who had withdrawn from the plot in tortured anxiety). As they gathered at the kitchen near Freeland’s house, Frederick spied four white men on horseback, and two blacks walking with them, coming down the long lane into the property. Then came the aging and rotund William Hambleton riding at a gallop. After a brief consultation between Freeland and Hambleton, within seconds the constables seized Frederick and tied his arms with rope. Then they moved to the Harrises; John was subdued and tied, but Henry physically resisted, refusing to allow his hands to be tied by these men, who were armed. One constable drew his pistol, cocked it, and aimed it point-blank at Henry’s breast. “Shoot me! Shoot me!” shouted Henry in defiance. “You can’t kill me but once. Shoot!—shoot! and be d__d. I won’t be tied.” Then the whole group assaulted Henry, drove him to the ground, and subdued him in ropes. While all were distracted, Frederick threw his pass into the kitchen fire; later he instructed the others to eat theirs.11

In Freeland’s front yard, the four bound young men were fastened with ropes to three horses, guarded by the mounted constables, and prodded off on a fifteen-mile forced march to the county jail in Easton. Before departure, Mrs. Betsey Freeland, the landowner’s mother and Hambleton’s sister, who had long-standing affection for the Harris brothers, railed at Frederick as the corrupter of the innocent. “You devil!” she screamed at him. “It was you who put into the heads of Henry and John to run away. But for you, you long legged yellow devil, Henry and John would never have thought of running away!” Douglass, the bound prisoner, met her gaze, he says, with a look that matched her wrath. After three miles the coffle stopped in St. Michaels at Thomas Auld’s store, where Frederick’s owner interrogated and berated him. But Douglass tells us that he defied and responded to Auld in kind with a lawyerlike argument that no crime had been committed, no evidence existed, and logically no one had any case against him, except for the words of a betrayer. Then the journey resumed on the dusty road to Easton.12

All along the roadway, through little hamlets called Spencer’s Cove, Royal Oak, Kirkham, and Miles Ferry, crowds of what Douglass called “moral vultures” gathered to jeer, shout epithets, and indulge in “ribaldry” at the expense of the slave prisoners. Some yelled that Frederick should be hanged or burned. Such an event in rural slave country made for a spectacular break in routines and a feast for lurid rumors. Some slaves in fields, said Douglass, “cautiously glanced at us through the post-and-rail fences.” Fear spread like the fastest wind when slave rebellions or runaways were thwarted; the eye contact Frederick may have managed with his fellow slaves only made the mutual dread more contagious. Upon arrival after hours of travel, the coffle was untied and interrogated. Frederick had urged the others to deny everything, like the fledgling revolutionaries they had tried to be. “Own nothing!” had been their leader’s command while on the march.

They were placed in the stone jailhouse on the rear of the Talbot County courthouse, which still stands today. Behind heavy locks, bars, and iron latticework on the windows, for the first week of captivity the prisoners bonded again in their assumed fate—sale separately to the Deep South. They peered through the windows, wishing they could speak to one of the white-coated black waiters across the street at Solomon Lowe’s Hotel. Like a “pack of fiends, fresh from perdition,” slave traders, eager for new flesh for the Southern markets, lurked about the jail, taunting the prisoners and feeling their arms, legs, and shoulders to judge their fitness. This constituted the Eastern Shore’s active domestic slave trade, about to feed four new pieces of property down its trough greased with filthy lucre. Later, Douglass did not miss a beat in using these daily encounters with slave traders to show that, however much detested by polite society in the slave South, these “whiskey-bloated gamblers in human flesh” were necessary to the master class’s profit and expansion. The slave owner and the slave trader, declared Douglass, were partners in “blasphemy and blood.”13

The Talbot County courthouse. In the rear of this building Douglass was held in jail for two weeks after his aborted escape plan in 1836. Today his statue stands out front, unveiled in 2011. Postcard by Marian L. Covey, c. 1910.

At the end of that first week in jail, Freeland and Hambleton arrived to extract the other three young men and take them back to their farms without any punishment. In this dreaded separation from his friends, Fred Bailey felt a “solitary . . . desolation.” As ringleader, he now felt certain Auld would at any time arrive to sell him to Alabama or Georgia. For seven more lonely days Frederick fended off the probing hands and the insults of the traders and felt a volcano of rage and a numbing loneliness rising in him. When his tense and indecisive owner finally showed up, to Frederick’s great surprise Auld had decided not to sell his slave, but to send him back to Baltimore with the promise that for good behavior, and learning a trade, Auld would free him on his twenty-fifth birthday. This moment may easily have been the greatest stroke of good luck in Douglass’s life, and he seems to have known it. Auld could have sent him “into the very everglades of Florida,” wrote Douglass of this turning point, “beyond the remotest hope of emancipation; and his refusal to exercise that power must be set down to his credit.”14 After many weeks of deadly mischief, of hope sublime and fear unbearable, the wretched imprisonment and humiliation, Fred Bailey must have found a little skip in his step as he realized he would once again see those clipper ships in Baltimore harbor.

Why did Thomas Auld send Frederick back to Baltimore at age eighteen? How or why did he resist the $800 or more he might have pocketed on the sale of his slave to the cotton kingdom? Certainly his wife, Rowena, who detested Frederick, would have craved the money from the young rebel’s sale. The Freelands could now view Frederick only as dangerous and would have wanted him out of the neighborhood. And William Hambleton, Auld’s own father-in-law, apparently told Auld in no uncertain terms that he would shoot the young man if he was not sold out of Talbot County. Douglass later learned from his cousin Tom Bailey that Auld fretted a great deal over his decision and “walked the floor nearly all night” before going to the Easton jail to retrieve Frederick. Perhaps his Christian conversion and a personal disdain for the vulturelike slave traders at the Easton jail played some role as well in Auld’s choice. According to Douglass, Auld blustered for a day or two back in St. Michaels that he had an “Alabama friend” to whom he planned to sell Frederick. But the fictitious Alabamian never showed up. Auld may have hoped that as Frederick learned a trade, profits might be made from his labor in Baltimore. But it also appears that emotionally, Auld, whether because of extended family blood ties or out of watching this brilliant young rascal grow up for eighteen years, just could not bring himself to sell Frederick to a doomed fate. Auld had done Fred Bailey an extraordinarily good turn; it would be a long time before Frederick Douglass would fairly recognize the deed.15

• • •

Frederick had left Baltimore three years earlier as an awkward, despondent, long-legged boy; he returned in 1836 an approximately six-feet-one-inch, well-built young man, firm and strengthened by more than two years as a field hand, and, above all, more confident in mind and body. To Frederick, Baltimore was warmly familiar at first, but also greatly changed. The turbulent, increasingly violent city teemed with huge numbers of new Irish immigrant laborers. The free black population had rapidly risen to more than fifteen thousand, with an active community of churches and associations, while slaves numbered only just under four thousand. The Aulds had moved to Fells Street, just past the Shakespeare Alley, but still near the burgeoning docks and shipyards. Hugh’s fortunes had eroded; he lost his own shipbuilding firm and was now working as a foreman in another yard. Grown to near manhood, Tommy Auld had gone to sea as a sailor aboard a brig called the Tweed, never to be seen again.16

To bring in wages for himself, and to teach the slave a trade as a caulker, Hugh Auld hired out Frederick to William Gardiner’s shipyard, where the big builder employed at least one hundred men on breakneck schedules to fulfill a contract to construct two men-of-war for the Mexican government. The Gardiner yard was an exciting, and dangerous, place. Most of the carpenters were white, some were free blacks, and among the apprentices running about frantically at the beck and call of the older workers, Frederick may have been the only black. With all manner of racist taunts, white carpenters barked orders at Frederick: “Fred, come carry this timber yonder”; “Fred, bring that roller here”; “Fred! Run and bring me a cold chisel.” All day long the young man tried to answer to “Halloo nigger,” and “Say darkey,” while doing every nasty job at an impossible pace. For eight months, wrote Douglass, this provided the “school” in which he learned the trade of caulker.17

In this ugly racial atmosphere, and with Frederick now hardly willing to back down to anyone, the young white apprentices turned on him. “The niggers,” they said within his hearing, were taking white men’s jobs and should be banished. One day Frederick snapped after being cursed at by a large white fellow named Edward North; Frederick grabbed the white worker, wrestled him to a dock, and threw him in the water. Now a street fighter of necessity and perhaps some relish, Douglass later claimed he could handle any of these toughs “singly.” But he also found more mischief than he had bargained for. While pounding bolts into the hold of a ship, one bent, and a white worker named Ned immediately next to him shouted that it was Fred’s fault; Fred took offense and blamed the white man. The two of them each grabbed weapons, Ned an adze (an arc-bladed hand ax), and Fred a maul, and after lunging at each other with vicious intent, they suddenly stopped before one of them ended up dead. One day four of the white apprentices, whom Douglass later named—Ned North, Ned Hays, Bill Stewart, and Tom Humphreys—pounced on him with a brick and a “heavy hand-spike.” They beat him to the ground, and one of them landed a savage kick to his face, smashing his left eye, “which for a time, seemed to have burst my eyeball.” With Frederick bloodied all over, his eye swollen closed, the group seemed satisfied; but he staggered to his feet, and waving a handspike, ran after them as they fled.18

When Frederick limped home to the Aulds’ house, they met him with sympathy and outrage at his accidents. Sophia cried and tenderly nursed his wounds. The following day the enraged Hugh took Frederick to a justice of the peace to seek redress and arrests of the young men who had beaten his slave. But “Esquire Watson” could do nothing, he reported, without white witnesses; by law in Maryland, no black person could testify against a white person. Auld tended to follow the strictures of the slave codes, but in this case he fruitlessly protested. Douglass placed his memory of this event in a larger story of the new “murderous . . . spirit” of Baltimore; the city no longer provided a place of cosmopolitan dreams for a slave, especially since at least fifty white men had watched his beating, lifting no hand to stop it, as they shouted, “Kill the nigger!”19 When, less than six years later, we find Douglass tilting under the weighted strictures of his fellow abolitionists’ pacifism, we need only remember these bloody Baltimore fights and his experience in the proslavery criminal justice system to understand his ambivalence. A brawler of necessity, he would ultimately find philosophical nonviolence untenable.

Hugh removed Frederick from Gardiner’s for his safety and got him work at Price’s shipyard, where Auld was himself a foreman. There Frederick would learn well the craft of caulker and begin to take in from $6 to $9 per week. In this hothouse atmosphere of violence, racism, and embittered economic competition among an insecure working class, Frederick Bailey learned even deeper lessons about the natural struggle between labor and capital. In Bondage and Freedom, Douglass gave the economics of urban slavery and Southern race relations an astute analysis. Despite that thuggish white dockworkers had beaten and nearly killed him, Douglass keenly grasped the plight of the white poor. In their “craftiness,” wrote Douglass, urban slaveholders and shipyard owners forged an “enmity of the poor, laboring white man against the blacks,” forcing an embittered scramble for diminished wages, and rendering the white worker “as much a slave as the black slave himself.” Both were “plundered, and by the same plunderer.” The “white slave” and the “black slave” were both robbed, one by a single master, and the other by the entire slave system. The slaveholding class exploited the lethal tools of racism to convince the burgeoning immigrant poor, said Douglass, that “slavery is the only power that can prevent the laboring white man from falling to the level of the slave’s poverty and degradation.” Douglass imagined a time when white and black carpenters had worked peacefully side by side in the Fell’s Point shipyards. He wrongly predicted that all these “injurious consequences” sowed by the master class would one day inspire the white non-slaveholding poor to rise in solidarity with slaves.20 As later in his career, Douglass’s economic analysis could alternate between astute and naïve, but he certainly understood class consciousness.

With historical distance, Douglass found sincere sympathy for those poor white workers who had pummeled and kicked him. But back in 1837–38, trying to garner wages as a hired slave, he kept his fists clinched. His stories have become so iconic today that the scene has even appeared in a major work of literature, Sea of Poppies (2008), by Amitav Ghosh. Ghosh tells an epic tale of a ship, the Ibis, built originally in Gardiner’s shipyard in Baltimore and used in the illegal slave trade, heading out around the Horn of Africa for a voyage into the Indian Ocean. Aboard is a young seaman, a mulatto American freedman named Zachery Reid. After months at sea and much sickness and death among the crew, Zachery’s mind “travels aback across the oceans to his last day at Gardiner’s shipyard in Baltimore.” He sees again “a face with a burst eyeball, the scalp torn open where a hand-spike had landed, the dark skin slick with blood.” In his vision, Zachery sees “the encirclement of Freddy Douglass, set upon by four white carpenters; he remembered the howls, ‘kill him, kill the damned nigger!’ ” He recalled how he and the other free black workers had “held back, their hands stayed by fear.” Zachery hears “Freddy’s voice” in his head, “not reproaching them [his fellow black workers] for not coming to his defense, but urging them to leave, scatter: ‘It’s about jobs; the whites won’t work with you, freeman or slave: keeping you out is their way of saving their bread.’ ” It was then, says Ghosh, that Zachery quit the shipyard and went to sea.21 In 1837 “Freddy” was still yearning to get out of those shipyards himself.

In the relative safety of Price’s shipyard, Frederick found better days in 1837 and 1838; he began to read again, and most important, he joined in the life of the large free black community of Baltimore, especially a debating and social organization, the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society. Here Frederick could let down his guard and employ his favorite weapons—words, and the growing charisma he cultivated while using them. He “was living among freemen,” he recollected, and resented every aspect of his slave status against the lives of his free friends, especially the necessity of depositing most of his wages with Hugh Auld every Saturday night. Frederick chafed under such brutal contradictions. At nineteen and soon twenty years old, his future made no sense to him: “Why should I be a slave?” he recalled thinking. “There was no reason why I should be in the thrall of any man.” Frederick made fast friends among a new band of brothers, especially five—James Mingo, William E. Lloyd, William Chester, Joseph Lewis, and Henry Rolles. Sometimes they met in Mingo’s “old frame house in Happy Alley” and debated racial, religious, and political issues. One of them, Lloyd, wrote to Douglass in 1870, remembering that one night Frederick waxed so excited with his oratory that “you told me you never meant to stop until you got into the United States Senate.”22 Fred Bailey’s speaking career began first on Freeland’s farm and then in Happy Alley in Baltimore.

At one of the social gatherings of the debating society, or perhaps as likely at the Sharp Street AME Church, which Frederick joined, he met a young, dark-skinned free woman who liked music named Anna Murray. Anna was born in or around 1813, near Denton, in Caroline County, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, within three miles or so of where Frederick was born. Their childhoods may have overlapped for a year or so in this region known as the Tuckahoe Neck; they knew each other’s families, although Anna’s had been more intact, and they had played at the same mill and wandered as kids in and out of Hillsborough. Anna was the seventh of twelve children born to Bambarra and Mary Murray, both slaves; but because of the manumission of her mother, Anna was the first born free. At age seventeen, likely in 1830 or 1831, while Fred Bailey was twelve or thirteen and living with Hugh and Sophia Auld, reading the Bible with Father Lawson, and combing through his Columbian Orator, Anna, with three siblings, Elizabeth, Philip, and Charlotte, moved to Baltimore to find work and a better life than what the right bank of the Tuckahoe offered. For two years Anna found employment as a housekeeper for a French family named Montell. Then, perhaps for as long as five years, she served the family of Mr. Wells, the postmaster of Baltimore, who lived on S. Caroline Street, only a half dozen or so blocks straight above Philpot and Thames, where Frederick lived during his years in the city.23

Dressed likely in a drab white or gray calico dress and apron by day, Anna may have donned a special head scarf and a prettier dress on whatever day or evening she met the strapping nineteen- or twenty-year-old brainy slave from the Eastern Shore. They may have known each other simply from passing in the streets, but when they met, they must have fallen into a long, smiling conversation about where they were from, the people they knew (each other’s cousins), and stories of growing up along the Tuckahoe. Finding Frederick was not the only reason Anna had moved to Baltimore as a teenager, but she surely must have thought so now. And Bailey, perhaps still a bit awkward around young women, must have craved Anna’s admiration, emotional support, and adoring eye contact. She was older, had lived in this free black community for years, and perhaps gave the young slave some credibility among his new friends. She may have even provided caring advice on how to take care of his injuries and scars from the rumbles down on the docks. Somewhere between Caroline and Thames Streets the two fell in love and discovered they needed each other. Douglass had found a woman who would help him imagine a new life.

Anna worked for her meager wages for the Wells family and as part of a burgeoning group of free black women struggling for domestic-service positions in white people’s homes. Anna did manage to save some money and owned two feather beds and other household goods when she became engaged to Frederick; but her daily life was a battle against poverty, paying rent for her lodging, buying firewood, always striving to be the efficient and prim housekeeper the Wells family expected. In her twenties, she was one lonely worker who, as historian Seth Rockman aptly wrote, “scraped by on the ‘economy of makeshift.’ ”24 Frederick needed a helpmeet with whom to dream and plan his way out of Maryland, and Anna needed a future that might not include carrying white people’s chamber pots every morning.

Frederick absolutely hated Hugh Auld’s “right of the robber” in taking the slave’s earnings. Here Frederick was again, now twenty years old, treated as a boy serving the ends of white people who still owned his body and his labor. His troubles, he maintained, as ever, were “less physical than mental.” Remembering these last months of his time in Baltimore, Douglass penned another gem about the psychology of slave and master: “To make a contented slave, you must make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and as far as possible, to annihilate his power of reason. . . . The slave must know no Higher Law than his master’s will . . . if there be one crevice through which a single drop can fall, it will certainly rust off the slave’s chains.” Frederick’s chains had long since rusted into powder, and a mental and pecuniary tug-of-war now ensued between Auld and his slave that forced the young man to a desperate flight for freedom. In the spring of 1838, Frederick and Hugh made a deal, allowing the slave to take his own lodgings, hire his own time, and keep any wages above $3 per week. From May until August 1838, Frederick worked hard, bought his own caulking tools, and forged more personal time to, perhaps under Anna’s influence, take up music at church. Above all, work itself now seemed to equate with liberty.25

Until Frederick went to a camp meeting one Saturday night some twelve miles from Baltimore and, having a grand time, stayed until Monday, thus missing his payment time (Saturday night) by forty-eight hours. Upon his return, Auld was furious, threatened to whip the grown man, and accused him of plotting to run away. The owner rescinded Frederick’s “partial freedom”; he could no longer hire himself and keep part of his wages. Sulking for at least a week, Frederick refused to go to work at all; Auld, in his fury, verbally abused the lad, threatened beatings, and even sale. With genuine fear that Hugh and Thomas Auld might indeed finally sell him south, Frederick and Anna, with the assistance of other free black friends, hatched his escape plot.26

• • •

Over the next three weeks, Frederick worked hard down at the yards so as to dispel Auld’s suspicion of a scheme. On one Saturday, the spiteful master took Frederick’s $9 and gave him back a puny twenty-five cents. Between the two of them, Frederick and Anna pooled resources to buy him a real train ticket, as well as the symbolic “fare,” as he wrote, “on the underground railroad.” His plan required cunning, courage, and luck, not to mention Anna’s own devil-may-care bravery and material support. According to family lore, Anna sold one of her feather beds to raise cash for Frederick’s journey. With a terrible sense of “internal excitement and anxiety,” the pain of separation from the only friends he possessed, and memories welling up from the Freeland-farm debacle of two years earlier, Frederick searched for someone’s “free papers” to use at various checkpoints. A friend from Fell’s Point, a retired black sailor named Stanley, provided the young man with his “sailor’s protection,” a remarkable document never to be forgotten with an American eagle at the top of the page. Nothing was fail-safe, and a cautious person would never have attempted this plot. Frederick obtained clothing to present himself in full “sailor style . . . red shirt and a tarpaulin hat and black cravat, tied in sailor fashion, carelessly and loosely about my neck.” It would be quite a performance; he knew the language of ships and sea and declared himself ready to “talk sailor like an ‘old salt.’ ”27

On the appointed day, Monday, September 3, 1838, Frederick went to work early, then met Anna on the way to the Wilmington and Baltimore train station just a few blocks above the City Dock. With tears and an embrace Anna sent her sailor boy pacing back and forth near the waiting train. So that he would not have to face the scrutiny of a ticket window, Frederick had arranged for his friend and drayman Isaac Rolles to bring Frederick’s baggage along just as the train started moving; the boy from the bend in the Tuckahoe jumped on the crowded Negro car and began the most famous escape in the annals of American slavery.28

With excited fear, Anna retreated to a workday at the Wells house and to several days of anguished waiting for some sign of the good word. What could she have thought? He will make it to a place far north called New York? He will go all the way to Canada, to worlds way beyond the horizons of Chesapeake Bay? I too will ride that train to join him somewhere? I will never see him again? He will be returned within the day in ropes and chains, bloodied, soon to be shipped south and out of my life? She too had her bags packed; controlling her outward emotions, even eating and sleeping, must have seemed impossible. She probably prayed in all her quiet moments.

As the train churned toward Havre de Grace, Maryland, a distance of thirty-seven miles to where the Susquehanna River empties into the top of Chesapeake Bay, Frederick encountered his first danger; the gruff conductor meandered through the car checking tickets and documents (the sailor Stanley was much darker in complexion than the mulatto Fred Bailey), but softened in the face of such a young sailor, for whom Douglass maintained there was widespread social respect. The conductor barely glanced at that eagle on his document, and the fugitive’s sudden terror subsided. At Havre de Grace passengers boarded a ferry to cross the Susquehanna; Frederick had to do his nervous best to shake a young black boat worker who kept up a steady questioning of the well-attired sailor’s origins and destinations. Now, for approximately another thirty-seven miles, half through Maryland and half through Delaware, slave states, the train trudged on. “Minutes were hours, and hours were days,” Douglass recalled of his drama. “The heart of no fox or deer, with hungry hounds on his trail,” said the autobiographer, had ever beat “more anxiously or noisily.” At a stop, Frederick looked out his window and immediately next to him in the opposite window of a train heading in the other direction was a ship’s captain named McGowan, on whose revenue cutter the young caulker had just worked the week before. He knew McGowan would recognize him, but the captain never turned his head or made eye contact. Then Douglass encountered a German blacksmith he knew from the Baltimore shipyards, who looked him over knowingly but thankfully “had no heart to betray me.”29

At Wilmington, Delaware, Frederick coyly, if rapidly, walked through town from the train station to the wharf, where he boarded a steamboat that soon set out into the “broad and beautiful Delaware” River. Arriving in Philadelphia in late afternoon after thirty unmolested miles on the steamer, Frederick walked off the gangplank onto free soil for the first time. He wasted no time in relishing the moment and asked the first safe-looking black man he saw how to find the train to New York. Directed to the Willow Street station, Edward Covey’s broken bondsman paid the fare and took the night train up through New Jersey to the Hudson River landing and railroad terminus in Hoboken. There, around sunrise on Tuesday, September 4, Frederick boarded a ferry that chugged southeasterly across the mighty Hudson River to a dock at the end of Chambers Street.30 On a bright September morning, with the sounds of snapping waves and the shouts of men’s voices along the wharves, Harriet Bailey’s lost orphan stepped into the busy streets of New York, wide-eyed, thrilled, and frightened.

Douglass later struggled for those magical words to describe his feelings that special morning. “Walking amid the hurrying throng, and gazing upon the dazzling wonders of Broadway,” he felt the sensation of a “free state around me, and a free earth under my feet! What a moment was this to me! A whole year was pressed into a single day. A new world burst upon my agitated vision.” But these sensations stymied this eventual word master, he admitted. They were “too intense and too rapid for words.” He later managed a little poetry nonetheless. “Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be described, but joy and gladness, like the rainbow of promise, defy alike the pen and pencil.” Although he was careful about whom to speak to in those dangerous streets, he remembered words from inside his soul like a shout: “I was a FREEMAN, and the voice of peace and joy thrilled my heart!”31 On that morning the words swirling in his head would have been the frightened fragments of a fugitive, eyes darting this way and that, wondering which impulse to trust. It took some years in the development of his genius with language for Douglass to shape this, and many other parts of his story, into the tale of the ascendant barefoot slave boy who would go forth and change the world.

Hungry and friendless, Frederick soon realized he still stood in “an enemy’s land” and had no time for odes to joy. In reality, Fred Bailey had escaped Maryland slavery with extraordinary bravery, but now he was a disoriented fugitive without any real plan. Numbed by loneliness, he trusted no one; every white man appeared as a potential kidnapper, and every black man a possible betrayer. He felt like everyone’s “prey” in the great metropolis. Later in his career as he portrayed over and over for abolitionist audiences the experience of the “panting fugitive,” he knew exactly of what he spoke. For at least one and possibly two nights, Frederick slept among the barrels at the wharf. By day he encountered a fellow fugitive he recognized from Baltimore, known in slavery as Allender’s Jake. Jake warned Frederick at length about ever-present slave catchers. Then he met a black sailor named Stewart, to whom he entrusted his story, and by whom he was directed to the house of David Ruggles, on 36 Lispenard Street at the corner of Church Street, a mere four or five blocks from the wharves.32 This was good fortune to rank along side the day Thomas Auld decided to send his slave back to Baltimore at age eighteen.

Ruggles was a free black grocer, abolitionist, newspaper editor, and especially the leader of the New York Vigilance Committee, the organization that openly and clandestinely aided fugitive slaves within and through New York City. From his house, Ruggles edited the Mirror of Liberty, America’s first black-owned and operated magazine, which printed reports of the Vigilance Committee’s legal and illegal work on behalf of runaway slaves. In his house he also maintained an essentially public reading room, with antislavery books and newspapers aplenty. Ruggles, who was just then in and out of court, and for a time under arrest, for his role in advocating for a Virginia fugitive, Thomas Hughes, who had accompanied his owner, John P. Darg, to New York, found time to take the ragged Frederick under his roof and guidance. Here in Ruggles’s reading room, amid the roiling controversy over the life and future of a fellow fugitive, and even at the courtroom where Frederick attended and witnessed his host’s testimony, the Maryland slave first encountered the exciting and dangerous daily world of abolitionism.33

Frederick spent at least a full week sheltered at Ruggles’s house. In some idle moment, his host suggested a speedy name change, and like so many other runaways seeking anonymity, Frederick decided to become Frederick Johnson. That name would last only for several days until his later arrival in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he would take the name Douglass. Most important, as quickly as possible, Frederick wrote a letter to Anna in Baltimore, which Ruggles mailed for him. The letter, in a prearrangement, was likely addressed to one of the good friends Frederick had made in the debating society, who quickly, on or about September 10, rushed to Anna, who could not read, with the news that she was to take the train as soon as possible to New York. No one ever recorded or told the story of Anna’s brave train and steamer journey, also done in twenty-four hours, leaving the only environments she had ever known, abandoning her paying job, to join her lonely, directionless fiancé, to attempt to make a life somewhere up north. But away she went, and according to her daughter Rosetta, among the household goods she carried in a trunk was a “plum colored silk dress” that, three days after her arrival, on September 15, she wore to be married to Frederick Johnson in the small parlor of Ruggles’s home.34

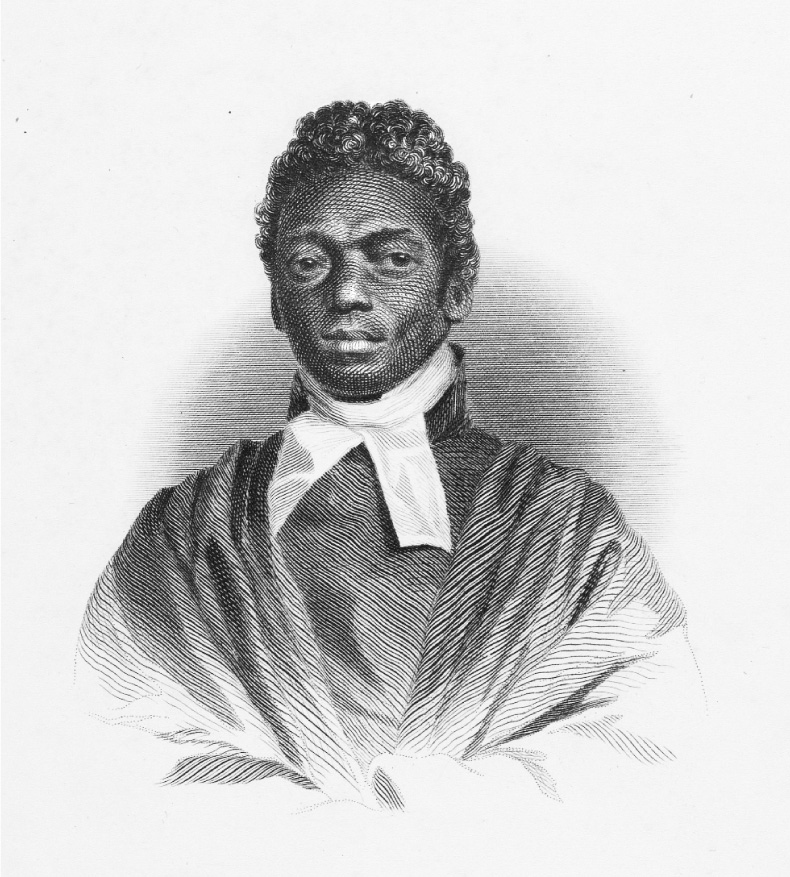

To conduct the wedding, Ruggles invited the Reverend James W. C. Pennington, who had himself escaped from slavery near Rockland, Maryland, in 1827 when, like Frederick, he was twenty years old. Born James Pembroke, he had run overland and found shelter with Quakers in Adams County, Pennsylvania, before moving on to New York and Connecticut. Like other fugitives, he had changed his name, and after working as a blacksmith, he became a minister, pastoring both Congregational and Presbyterian churches in New Haven, Connecticut, and Brooklyn, New York. Like Frederick, his residence as a city slave had led to his desire to seek learning and freedom. Pennington had vigorously sought admission to classes at the Yale Divinity School, only to be rejected. James and Frederick had much to discuss, although it was wedding day, but Douglass left no account of conversations between the two fugitive slaves. Pennington left Mr. and Mrs. Johnson with a short certificate of their marriage, the text of which Douglass reprinted in the Narrative, as though he needed to display an official declaration of such a human and liberating act as marriage on free soil.35

James W. C. Pennington. Pennington escaped from slavery in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. Engraving on paper.

Sensing that Frederick had no plan other than some vague idea of going to Canada, Ruggles firmly urged the newlyweds to move up the New England coast, to New Bedford, Massachusetts, a whaling port, where Frederick could find work as a caulker, and the couple would find a welcoming fugitive-slave and free-black community. Ruggles gave Frederick a $5 bill, and with no further ceremony, Douglass tells us he lifted the larger part of their luggage (which contained his beloved Columbian Orator and three song booklets) on his shoulder, while Anna carried the smaller bags, and they strode across lower Manhattan to the docks to embark on the steamer John W. Richmond. Full of gratitude for David Ruggles, that “whole-souled man, fully imbued with a love of his afflicted and hunted people,” Frederick had quickly and happily gone from teacher to pupil.36 Two strong and courageous black abolitionists had shown him the way. Holding his intrepid bride’s hand, Frederick stepped beyond three years of bloody and beautiful mischief into freedom.