Corinthian Hall, Rochester, New York, 1850s. Lithograph.

I have this day set thee over the nations and over the kingdoms, to root out, and to pull down . . . to build, and to plant.

—JEREMIAH 1:10

Frederick Douglass had learned the hard way that oppression, loss, and anger had to be controlled and braced with knowledge if a former slave with an extraordinary mind was to survive in the United States. He was a man of the nineteenth century, a thoroughgoing inheritor of Enlightenment ideas, but for justification, and for the story in which to embed the experience of American slaves, he reached for the Old Testament Hebrew prophets of the sixth to eighth centuries BC. Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel were his companions, a confounding but inspiring source of intellectual and emotional control. Their great and terrible stories provided Douglass the deepest well of metaphor and meaning for his increasingly ferocious critique of his own country. Their Jerusalem, their temple, their Israelites transported in the Babylonian Captivity, their oracles to the nation of the woe to be inflicted upon them by a vengeful God for their crimes, were his American “republic,” his “bleeding children of sorrow,” his warnings of desolations soon to visit his own guilty land.1 Their story was ancient and modern; it gave the weight of the ages to his cause. Their awesome narratives of destruction and apocalyptical renewal, exile and return, provided scriptural basis for his mission to convince Americans they must undergo the same. The Old Testament prophets helped make Douglass a great ironist and a great storyteller; they fueled his growing militancy and brought pathos and thunder to his voice as they also shaped his view of history itself. Douglass not only used the Hebrew prophets; he joined them.

The Hebrew prophets delivered their sayings and poems orally in public gatherings. Whether Douglass understood this or not, it makes his oratorical use of the jeremiadic tradition all the more poignant. As Isaiah “came . . . and said,” and Jeremiah followed God’s call to “go and cry in the ears of Jerusalem,” so Douglass proclaimed antislavery oracles to vast public audiences in proslavery America. God had visited Jeremiah and instructed him, “Behold, I have put My words in your mouth,” and given him his calling. Beginning with the black churches he attended in Baltimore, where he would have first heard preaching on the Exodus story, Douglass had reached that moment as well. He was an American Jeremiah chastising the flock as he also called them back to their covenants and creeds. Moreover, Douglass, like other American writers and orators from the Puritans to modern times, found his own way to comprehend as well as rewrite Old Testament narratives, in the words of biblical scholar Robert Alter, as both “sacred history” and “prose fiction,” as models of literary style and a national story. And as the Jewish theologian Abraham Heschel wrote, “Prophets must have been shattered by some cataclysmic experience in order to be able to shatter others.”2 By this standard, Douglass qualified.

• • •

In early summer 1852, surrounded by rumors about his relationship with Julia Griffiths, suffering periodically with ill health, and embroiled in his fight with the Garrisonians, Douglass was invited by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society to deliver a Fourth of July address in the majestic Corinthian Hall, only a few blocks from the North Star’s office. Maria G. Porter was president and Griffiths the secretary of the society, which in late March had raised $233 at a festival to support Douglass’s newspaper. The society sponsored a regular series of antislavery lectures in Corinthian Hall, announced by Griffiths in Douglass’s paper. In accepting the invitation, he insisted on delivering the speech on July 5, which had long been a practice among New York State African American communities. In the South, moreover, slave auctions had often been conducted on July 4, further sullying the date in African American memory. The Fourth fell on a Sunday, and for that reason also the Rochesterites moved it to Monday. For at least three weeks in advance of the event Douglass worked hard on the text, as well as personally promoting the event in his paper. He clearly aimed the speech not only at his local audience but beyond the hall to the nation at large. Immediately after the oration he had it printed in bulk and sold it in his paper as well as out on the lecture circuit at fifty cents per copy, or $6 per hundred.3 What Douglass crafted and delivered on July 5 was nothing less than the rhetorical masterpiece of American abolitionism.

Nearly six hundred people packed Corinthian Hall on that warm July day; a “grand dinner” was prepared by the Ladies’ Society for after the speech. The beautiful edifice, which took its name from four Corinthian columns adorning the high front wall, had just opened in 1849 and was Rochester’s most prestigious venue for concerts, lectures, balls, and fairs. Four great chandeliers hung from the high ceiling, and tall windows on both sides admitted plentiful natural light. The buzz of mass conversation quickly fell silent as local abolitionist James Sperry called the meeting to order. The Reverend S. Ottman of Rush, New York, delivered a prayer, then the Reverend Robert R. Raymond of Syracuse performed a reading of the Declaration of Independence. Without introduction, sporting his high white collar, vested suit, and large mane of hair carefully parted, Frederick Douglass stepped forward, his hands slightly trembling with the thirty-page text he held.4

In a conventional apologia audiences came to expect, he began quietly with a disclaimer of his ability to address such an august assembly: he had never appeared more “shrinkingly” before an audience. He knew such disclaimers were taken by his auditors as “flat and unmeaning,” but he begged their indulgence of his awareness that this was something special; he knew he spoke in the house of his friends, whom he now used as stand-ins for the nation. In an old move of false self-deprecation, he said the “distance between this platform and the slave plantation, from which I escaped, is considerable” and left him with a “quailing sensation.” Wishing he had had time for more “elaborate preparation” and more formal “learning,” Douglass finally reached his subject.5 Invited to participate in a celebration of American independence, Douglass delivered a political sermon, steeped in the Jeremiah tradition.

Douglass’s Fourth of July speech came in the midst of many turbulent contexts. Douglass faced the personal crises of his own life just discussed, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin had become an instant phenomenon. For nearly two years free blacks and their allies had defied the hated Fugitive Slave Act. Massive protest meetings condemned a law that denied the right of habeas corpus and trial by jury to alleged fugitive slaves, as well as threatened the kidnapping of free people of color into slavery. Douglass himself had stepped up his assistance to runaway slaves in Rochester and participated in recent months in some of the clandestine rescues of fugitives across the North. Now, under the American flag, observed Douglass, so deep was the fear in Northern black communities that hundreds had fled to Canada like “a dark train going out of the land, as if fleeing from death.” In virtually every issue of his paper, Douglass and his staff ran articles and reports about kidnappings or escapes of “refugee” slaves in the North or into Canada.6 And as abolitionists turned more toward violent means of resistance, and political parties began to tear themselves asunder, the country faced another general election in the coming fall.

Douglass channeled all of this tension into a kind of music; his speech was like a symphony in three movements. In the first movement, Douglass set his audience at ease by honoring the genius of the founding fathers. He called the Fourth of July an American “Passover” and placed hope in the youthful nation, “still impressible” and open to change. “Three score years and ten is the allotted time for individual men,” said the calm Douglass, “but nations number their years by thousands.” As he began a historical tribute to the bravery of the American revolutionaries of 1776, subtly referencing Thomas Paine’s times that “tried men’s souls,” he dropped hints of foreboding, of “dark clouds . . . above the horizon . . . portending disastrous times.” He began with hope, though: “There is consolation in the thought that America is young. Great streams are not easily turned from channels, worn deep in the course of ages.” Douglass called the Declaration of Independence the “RINGBOLT to the chain of your nation’s destiny,” and the preamble the nation’s “saving principles.” With active, gleaming metaphors landing on his listeners in every spoken paragraph, the music became louder. “From the round top of your ship of state, dark and threatening clouds may be seen,” Douglass sang. “Heavy billows, like mountains in the distance, disclose to the leeward huge forms of flinty rocks! That bolt drawn, that chain broken, and all is lost. Cling to this day—cling to it, and to its principles, with the grasp of a storm-tossed mariner to a spar at midnight.”7

His baritone voice now projecting to the rear of the hall, Douglass had laid the groundwork of prophetic irony in the first movement for the main argument to come. The scene-setting beauty of the string instruments soon gave way to full-throated horns and kettledrums. The warnings already lay in the politicized possessive pronouns: “your fathers,” “your national independence.” America’s story of its founding in the Revolution and its aftermath was taught, Douglass intoned, in “your common schools, narrated at your firesides, unfolded from your pulpits . . . as household words . . . the staple of your national poetry and eloquence.”8 A voice truly free and independent had arrived.

Then, as though slamming his fist down on the lectern, Douglass announced the shift to the second and longer movement of the symphony—a new version of that national poetry. Quoting Longfellow’s poem “A Psalm of Life,” he announced that his concern was the present: “Trust no future however pleasant, / Let the dead past bury its dead; Act, act in the living present, / Heart within, and God overhead.” As Douglass reminded his largely white audience of their national and personal declension, the speech found its theme—the hypocrisy of slavery and racism in a republic. He harkened to Genesis and Exodus and the twelve children of Jacob boasting of Abraham’s paternity but losing Abraham’s faith. This great human folly was both “ancient and modern,” Douglass proclaimed. The children of Israel “contented themselves under the shadow of Abraham’s great name, while they repudiated the deeds which made his name great.” For Americans, said Douglass, George Washington was the Abraham of their new Israel; and though Washington had freed his slaves in his will, “his monument is built up by the price of human blood, and the traders in the bodies and souls of men.”9 Complicit in the oldest stories in their spiritual and national lives, the audience sat primed for the onslaught to follow. The oracle turned wrathful.

Now Douglass brought his hammer down even harder, and for approximately fourteen pages, the second and longest movement rained down like a hailstorm. He pulled no punches, making the good abolitionists and the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society squirm as he dragged them through a litany of America’s contradictions. Second-person pronouns crashed into his singular “I.” “Fellow-citizens,” he firmly stated, “pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?” Douglass personified all slaves, past and present. “I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me by asking me to speak today?” Then, in the most beautiful move in the speech, he warns that “there is a parallel” as he flows unannounced back to the captivity of the ancient Jews in Psalm 137:

By the Rivers of Babylon, there we sat down. Yea! we wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there, they that carried us away captive, required of us a song; and they who wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.

Douglass’s answer to the summons? He would not sing any praise songs on the nation’s birthday. Instead, he recrafted Jeremiah’s tales of God’s wrath and the people’s mourning as he proclaimed, “Above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are today, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.”10

Douglass loved the Declaration of Independence, but since its principles were natural rights, like the precious ores of the earth, he refused to argue for their existence or their righteousness against the claims of proslavery ideologues. “What point in the antislavery creed would you have me argue?” he asked. Why must he prove that the slave is human? Rather, Douglass claimed his authority from two great scriptures, “the Constitution and the Bible,” and announced that “the time for argument is passed.” Instead, the American condition demanded “scorching irony.” Douglass had not come to Corinthian Hall for polite discourse. “O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would today pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened . . . the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed.”11 And so for twenty-five minutes—the second movement—he did just that.

Douglass poured out a litany of historical and contemporary evils caused by American slavery. He did not merely call Americans hypocrites; he showed them and made them feel, see, and hear their “revolting barbarity” in aggressive language. First, he delivered a thoroughgoing condemnation of the domestic slave trade. As lyrical as it was terrible, Douglass made his audience look at the “human flesh-jobbers” who operated the slave markets, hear their “savage yells and . . . blood-chilling oaths . . . the fetters clank . . . and the crack . . . sound of the slave-whip” and indeed “see” the slave mother’s “briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms.” He forced them to “attend the auction” and look on the “shocking gaze of American slave-buyers.” No one could do this quite like Douglass, who personified the terror by telling of his own memories of hearing the “rattle of chains and the heart-rending cries” from the slave coffles along the docks of Baltimore.12

Douglass next blasted the Fugitive Slave Act and the proslavery stances of American churches. The new law demanding complicity by Northerners in the retrieval of fugitive slaves, he told his countrymen, transformed “your broad republican domain” into a “hunting ground for men.” Everyone must now practice “this hellish sport,” including “your President, your Secretary of State, your lords, nobles, and ecclesiastics . . . as a duty you owe to your free and glorious country.” Withering sarcasm indeed. The sheer corruption of the Fugitive Slave Act, which mandated paying commissioners double the money for consigning a runaway back into slavery as opposed to allowing his freedom, could only be matched, said the orator, by the “flagrantly inconsistent” practices of the churches who willingly served as the “bodyguards of the tyrants of Virginia and Carolina.” In Douglass’s unrelenting staccato labeling, the “tyrant-killing, king-hating, people-loving, democratic Christian defenders” of the Fugitive Slave Act were no better than the pious “scribes, Pharisees, hypocrites who pay tithe of mint, anise, and cumin” at the temple rather than act with “mercy and faith.” Far too many clergymen, said Douglass, mouthed the words of the Declaration of Independence but in their religious practice only abetted the “tyrants, man-stealers and thugs.”13

So he pulled Isaiah from his arsenal and delivered what he believed the churches deserved: “Bring no more vain oblations; incense is an abomination unto me; the new moons and Sabbaths, the calling of assemblies, I cannot away with; it is iniquity . . . I am weary to bear them; and when ye spread forth your hands I will hide mine eyes from you. Yea! When you make many prayers, I will not hear, YOUR HANDS ARE FULL OF BLOOD; . . . cease to do evil, learn to do well; seek judgment; relieve the oppressed.”14 Douglass bore the news that the nation’s crimes stood condemned by the prophets of old in the people’s own sacred texts.

Douglass brought the second movement to a close in classic, frightening jeremiadic style. After one final long list of the ways slavery “brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity a lie,” he begged his audience and the nation to break loose from their doom before it was too late. “Oh! be warned! be warned!” he shouted. “A horrible reptile is coiled up in your nation’s bosom; the venomous creature is nursing at the tender breast of your youthful republic; for the love of God, tear away, and fling from you the hideous monster, and let the weight of twenty millions crush and destroy it forever!”15 With such urgency and terrifying imagery Douglass took a breath and paused.

The short and final third movement began calmly with a firm embrace of the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution. That charter, though full of potential double meanings, was in Douglass’s view “a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT” full of “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.” There was still time to act, and legal and moral tools aplenty for his countrymen to save themselves. In a move common in the American jeremiad, Douglass ended with visions of hope. He counseled faith in three elements that had now taken root in his thought. First was the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution. Second was his oft-expressed belief in Divine Providence, in the idea that a moral force would in the end govern human affairs. Seeking again his justification in Isaiah, he confidently asserted, “There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. ‘The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain.” And third, he appealed to the “tendencies of the age” to modernity. “Change has now come over the affairs of mankind. The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city. Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. . . . Wind, steam, and lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together. . . . Space is comparatively annihilated. Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are distinctly heard on the other.” Keep faith, he urged Rochester and the nation at large, slavery could not hide from “light” itself.16

Having paid a kind of homage to Gerrit Smith with the fulsome statement on the Constitution, Douglass breathed one more famous passage from the Psalms into his own rhythms and on behalf of his race: “Ethiopia shall stretch out her hand unto God.” Then, remarkably, he paid an even fuller homage to Garrison and ended the speech with four verses of the abolitionist’s poem “The Triumph of Freedom,” a testimony of radical biblical devotion to cause:

God speed the year of Jubilee

The wide world o’er! . . .

Until that year, day, hour arrive . . .

With head, and heart, and hand I’ll strive.

In both secular and sacred terms, prescient in its vision and powerful in its unforgettable language, Douglass had delivered one of the greatest speeches of American history. He had transcended his audience as well as Corinthian Hall, into a realm inhabited by great art that would last long after he and this history were gone. He had explained the nation’s historical condition and, through the pain of his indictment and the force of his altar call, illuminated a path to a better day. Douglass the ironist had never been in better form as he converted collective suffering into something like national hope. As Douglass lifted his text from the podium and took his seat, nearly six hundred white Northerners stood and roared with “a universal burst of applause.”17

• • •

Douglass’s Fourth of July Address, and his political thought generally in the 1850s, are often remembered and interpreted for their “nearly always hopeful” character, as August Meier once put it. But this assessment hardly captures either the ideological transformations Douglass underwent or the tone, method, and spiritual resolve of his major speeches and writings. The making of Douglass as a political abolitionist in the 1850s should be grounded in the prophetic tradition in which he came to see himself. His was a kind of radical hope in the theory of natural rights, and in a Christian millennialist view of history as humankind’s grand story, punctuated by terrible ruptures followed by potential regenerations.18

The idea of prophecy is unsettling to the modern secular imagination. But the rhetorical, spiritual, and historical traditions on which Douglass drew so deeply envisioned the prophet as a messenger of God’s warnings and wisdom. The poetic oracles of Isaiah or Jeremiah, however bleak or foreboding, were prophetic speech, and therefore God’s voice. Douglass, a man of words, needed a language and a story in which to find himself and his enslaved people. Although he never portrayed himself as literally a messenger of God, he found such a language in the Hebrew prophets in whose words, as the theologian Abraham Heschel writes, “the invisible God becomes audible.” The “words the prophet utters are not offered as souvenirs,” wrote Heschel. “He undertakes to stop a mighty stream with mere words.” In Old Testament tradition the prophets were reluctant messengers; God chose them and not the other way around. God spoke through the burdened Jeremiah, who wrote hauntingly, “But his word was in mine heart as burning fire shut up in my bones, and I was weary with forbearing, and I could not stay.” Douglass felt this same fire of the words in his bones that must get out, although he was never so good at playing the reluctant visionary. The Old Testament prophets fit with Douglass’s temperament and his predicament. As James Darsey argues, “It is precisely because the prophet engages his society over its most central and fundamental values that he is radical.” Thus prophets are rarely welcome friends; they are always trouble to other people’s consciences. They are companions, but not easy companions. They are not “reasonable,” says Darsey; they do not abide “compromise,” and their role in the world is that of a sacred “extremist.”19 In the 1850s, Douglass relished and tried to perform just such a role.

American Jeremiahs wove the secular and sacred together in their repeated warnings and appeals for higher strivings. As a rhetorical device and as a conception of America, the jeremiad was as flexible as it was pervasive. America’s “prophets of doom” thwarted despair and alienation in the temporal vastness and redemptive destiny of their New Israel. Yet this was never the result of a mere temperamental optimism, a flimsy substitute for the kind of hope Douglass forged through enslavement, despair, violence, and his favorite biblical prophets. The land of Judah, after all, lay in utter ruin before God saw fit to redeem Jacob, to offer answers to whether there was “a balm in Gilead,” or finally a promise that “there is hope in thine end . . . that thine children shall come again to their own border.” For a man who frequently reinvented himself, Douglass saw America in dire need of the same transformation. He had read those prophets as he came to see himself, in some ways, as their descendant exiled in a new Babylon. And his people needed a story to believe in, one with the “radical hope,” as Michael Walzer has argued, contained in the Exodus story. “Exodus is a model for messianic and millenarian thought,” writes Walzer, “and it is also a standing alternative to it—a secular and historical account of ‘redemption’ . . . that does not require the miraculous transformation of the material world but sets God’s people marching through the world toward a better place in it.”20 For black Americans, Exodus is always contemporary, history always past and present.

Douglass was no formal theologian, but his political hope was hard earned, and he relished the ancient stories in which to find purpose. He did not sit back awaiting God’s entry into history; he argued for it in endless variations on the Exodus story. By the early to mid-1850s, he forged a worldview from these biblical roots, from Enlightenment doctrine, especially natural rights, and in the face of several issues and events through which he defined himself. First was the never-ending question of colonization—whether black people could be induced to voluntarily leave the United States and return to Africa—a matter thrust back into the faces of abolitionists in 1849 by Henry Clay and the American Colonization Society’s renewed embrace of the strategy.

From December 1850 into February 1851, Douglass delivered a series of formal Sunday lectures in Corinthian Hall. The furor over the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act as well as other issues compelled him to try his hand at such a series, which he intended, as he told Gerrit Smith, to “publish . . . in book form.” The hall was nearly packed on at least nine Sundays in these winter months, and Douglass approached his subjects—the nature of slavery itself, fugitive slaves and resistance, the “Slave Power” in the federal government, and colonization—with his usual rhetorical flare and humor, but also now with research. Douglass eagerly used his neighbors, friends, and curiosity seekers to try out his chops as the political commentator he had already become in the pages of his newspaper. “We are in the midst of a great struggle,” he announced in the opening lecture. “The public mind is widely and deeply agitated; and bubbling up from its perturbed waters . . . whose poisonous miasma demands a constant antidote.”21

By late January of 1851 his topic was colonization because Congress, the press, and Clay himself had “breathed upon the dry bones” of the scheme and given it another life. Since his earliest days of reading the Liberator, Douglass had encountered the colonization issue. Almost nothing prompted his ire quite like the recurring machinations of colonizationists, who could only imagine an American future through the impulse, as he put it, of “out with the Negroes.” When Clay and the American Colonization Society (ACS) announced a plan for voluntary removal to Africa by free blacks, by a line of steamers financed by the federal government, Douglass turned anger into opportunity. He hated all versions of colonization because it cut to the heart of American racism—the assumptions about African Americans’ inferiority, and their inability to cope and compete in a white-dominated society. Douglass saw everything at stake in the colonization debate. It did not matter to him whether the advocacy of colonizing blacks outside of America came from the great moderate slaveholding Whig Clay; the crusading antislavery journalist and editor of the New York Tribune Horace Greeley; Douglass’s former friend and coworker Martin Delany, who by 1852 launched a campaign for American blacks to emigrate to Central Africa or the Caribbean; or from Abraham Lincoln in 1861–62. Douglass considered it all “diabolical” at its core. He spared no words in his condemnations. The ACS had existed since 1816 as the “offender . . . and slanderer of the colored people,” its schemes only a plot to remove blacks from society. To Douglass colonization was never anything but “Satan” with the “power to transform himself into an angel of light—to assume the beautiful garments of innocence.” Even to a friend of abolition such as Greeley, Douglass declared in 1852 that colonization in any guise meant “ultimate extermination” for his people.22

On this grievance and others Douglass demonstrated that he would not merely denounce the issue but analyze it. He would mix his Old Testament rebukes with argument, wit, and exposition. In a February 1851 speech, “Colonization Cant,” Douglass made his aims explicit as a political critic. He had two choices for how to wield his pen and voice: “One is to denounce, in strong and burning words, such theories and practices.” This would be the “easiest and commonest.” But the other was to “illustrate and expose, by careful analysis.” Even when he may have felt weak against such powers as the largest-circulation newspaper in America (Greeley’s Tribune) or the longtime standard-bearer of the Whig Party (Clay), Douglass loved this kind of rhetorical contest. He expanded his reading, followed congressional debates closely, and laid down a brilliant testimony about both the injustice and the absurdity of colonization. He marshaled statistics about the growth and stability of the free black population in the Northern states and recommended Clay and his “pious” associates consult Exodus 1:10–12. As the children of Israel were made captive, their oppressors were called “to deal wisely with them lest they multiply . . . therefore they did set over them taskmasters, to afflict them with their burdens. . . . But the more they afflicted them, the more they multiplied, and grew.”23

When Clay argued in Congress that removing blacks from the country “with their own consent” was the “great project” of the age, Douglass assaulted Clay’s logic by suggesting that the republican revolutions of 1848 in Europe, building a transcontinental railroad across North America, land reform to end poverty the world over, and the effort to establish international arbitration to settle and end wars might rank higher. He shattered Clay’s notion of expecting black folks’ “consent” for removal. In the Kentuckian’s apparent regard for black people rested the real evil, as Douglass summoned Shakespeare’s Henry VIII to make his point: “My Lord, my Lord, I am much . . . too weak / To oppose your cunning; you are meek and humble-mouthed; / You sign your place and calling in full seeming, / With meekness and humility; but your heart / Is crammed with arrogancy, spleen and pride.” Oh, that history might have given us a public debate between Douglass and Clay. The black abolitionist was unrelenting: “If a highway-robber should at the pistol’s mouth demand my purse, it is possible that I should ‘consent’ to give it up. If a midnight incendiary should fire my dwelling, I doubt not I should readily ‘consent’ to leave it.” In such an imagined debate we can see the warring assumptions that were tearing America apart. “The highway-robber has his method,” Douglass declared, “the torturous and wily politician has his.”24

• • •

A second, and even more ascendant, issue around which Douglass forged his political consciousness was resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act and the uses of violence. Deep in his soul, Douglass had never relinquished his belief in the right of physical resistance. But nothing had ever forced him to clarify his principles like the reality of the Fugitive Slave law. From his home in western New York, and so close to the northern border, Douglass remembered watching countless fugitives “suddenly alarmed and compelled to flee to Canada.” This “dismal march,” as he called it, was a large exodus: an estimated twenty thousand blacks may have moved to Canada in the 1850s. In the fall of 1850, Douglass even reported that a “party of manhunters” had come to Rochester intending to seize him and wrest him back to slavery. He admitted to worrying whether his bill of sale and freedom letter from Hugh Auld would withstand legal challenge if he was seized. In speeches Douglass made great use of this threat. For a time, he said, he held up in a “loft, or garret” in his house, having alerted local friends to be watchful. The confrontation never happened, but Douglass made it clear, whether with firearms or other lethal weapons, he was prepared to “greet them . . . with a hospitality befitting the place and occasion.” To a cheering audience in Boston on October 14, 1850, he urged all Northern blacks to be “resolved rather to die than to go back.” If a slave catcher sought to take the slave back, shouted Douglass, he “will be murdered in your streets.” This was a new rhetoric born of a new reality; the man of words now found himself at the center of a crisis in which there were “blows to take as well as blows to give.”25

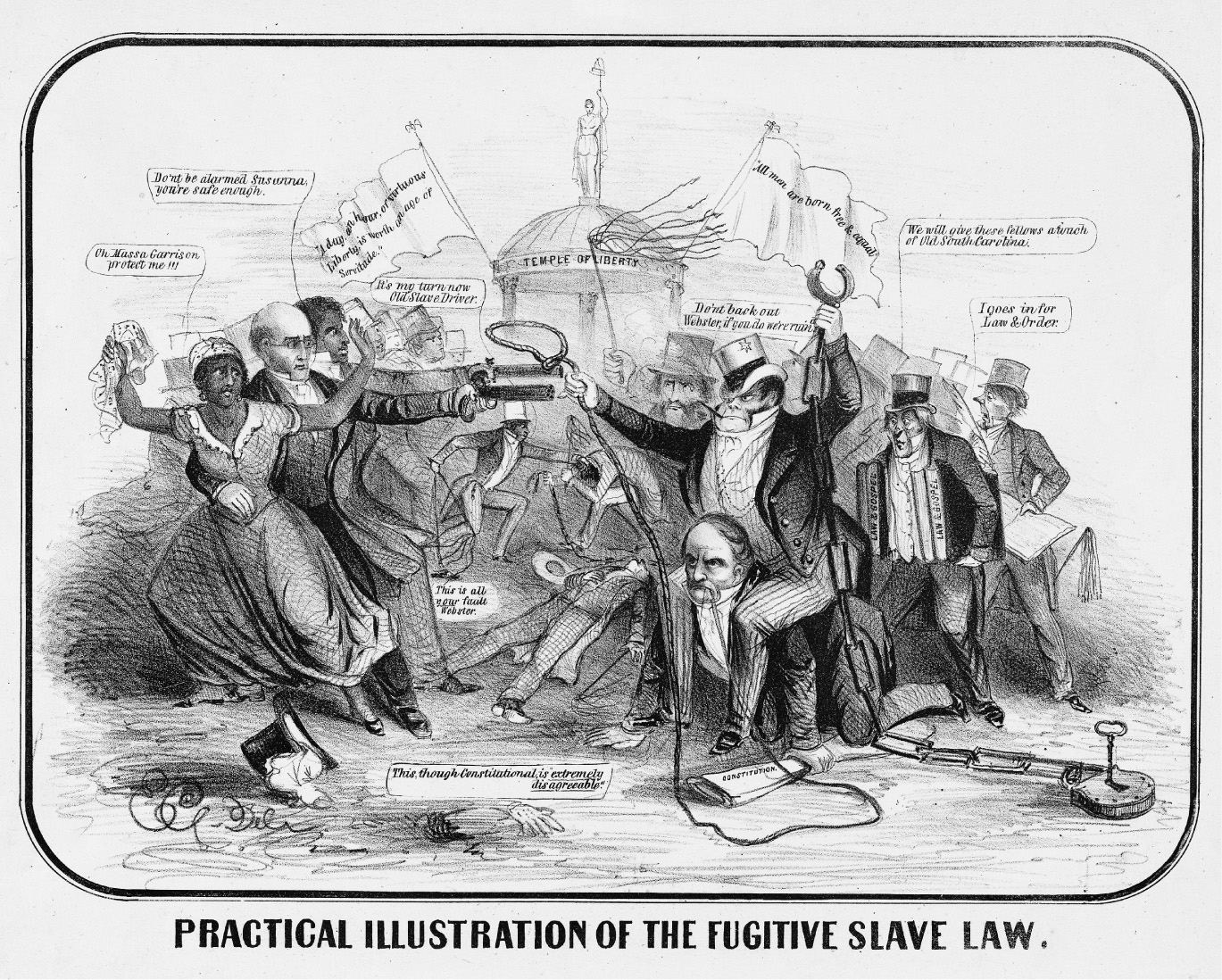

“Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law,” Currier & Ives cartoon, 1852. Note Douglass’s presence in the cartoon as part of the violent resistance with Garrison.

In a speech in Syracuse in early 1851, “Resistance to Blood-Houndism,” Douglass heightened the rhetoric. At a convention where Garrisonians attacked Douglass’s violent language as the “blood and murder” approach, he found allies among the few Liberty Party loyalists attending. “I am a peace man,” Douglass announced somewhat disingenuously. “But this convention ought to say to slaveholders that they are in danger of bodily harm if they come here, and attempt to carry men off to bondage.” He pleaded with his fellow abolitionists, most of them moral suasionists who had long preferred to “frown slaveholders down,” that they should seek “nothing short of the blood” of any slave catcher in their midst. The slaveholder who chooses the role of “bloodhound,” he continued, had “no right to live.” With bravado, Douglass spoke words that would stick to his changing reputation forever: “I do believe that two or three dead slaveholders will make this law a dead letter.” Such language had always been latent in the storehouse of Douglass’s personal memory; now it burst out with stunning furor, although he provided little advice on just how such a response was to be organized.26

Douglass had learned much from the Hebrew prophets, but in proslavery America he felt torn between their mixed messages on violence and war. He loved Isaiah’s brilliant condemnations of war; beating “swords into plowshares” is one of the most profound pleas in world literature. But he also harkened to the truth in Jeremiah’s injunction that in Babylon God’s “golden cup” of woe had made the nations “drunk” and “mad.”27 Just when was righteous violence a necessary evil, or even a good? The American Babylon now challenged the radical reformer to decide when vengeance was not only the best strategy, but right.

Many blacks and their white abolitionist allies did not need Douglass’s provocations to take to the streets to resist the law or rescue fugitives. Indeed, since the 1830s blacks in Northern cities and towns, from Boston to Pittsburgh and Philadelphia to Detroit, had organized in Vigilance Committees to protect fugitive slaves. Their leaders, such as David Ruggles in New York, who was so instrumental in Douglass’s own escape in 1838, had fought in the courts to secure former slaves’ freedom, as well as organized clandestine rescues of runaways seized by captors. Douglass paid tribute to these brave pioneers of resistance in an 1851 speech, naming some and honoring their courage to act as long as “a single slave clanked his chain in the land.” And in an October 1851 column in his paper, Douglass called the Fugitive Slave Act the “hydra . . . begotten in the spirit of compromise,” which assumed the “cowardly negro” who would not fight. But on the contrary, such “legalized piracy” had made the “government . . . their enemy.” He predicted that “the land will be filled with violence and blood till this law is repealed.”28 From late 1850 to 1854 numerous attempts were made to rescue former slaves from the grips of police powers, some violent, and with mixed success.

All across the North in black communities people held meetings and passed resolutions vowing resistance to slave catchers with “the most deadly weapons.” A new spirit of defiance fed on actual rescues of fugitives. Douglass cheered the news of the successful action in Boston in February 1851 when a Virginia fugitive, Shadrack Minkins, was rescued and spirited off to Canada. The outcome for Thomas Sims in April was not as good. A fugitive from Georgia, Sims was jailed and quickly convicted as white Massachusetts abolitionists worked unsuccessfully either to rescue or bribe him out of custody in Boston. He was returned to slavery even as hung juries refused to convict the many rescuers put on trial for the Minkins rescue. A rescue Douglass celebrated widely was that of Jerry Henry in Syracuse, New York, on October 1, 1851, where a mob born of a Liberty Party convention occurring in that city stormed a jailhouse and broke the fugitive out and took him to Canada. A large police dragnet and investigation led to some twenty-six indictments; no one was convicted, however, by local juries, and of those charged, among the twelve blacks, nine escaped to Canada and were never tried. Because it occurred closer to his own terrain in upstate New York, Douglass made the “Jerry Rescue” a staple of editorials and platform rhetoric as he built the case for the natural right of violent resistance to a law so at odds with human liberty.29

Just before the Jerry Henry rescue, in September 1851, Douglass got his own opportunity to directly aid fugitives escaping after violent resistance. At the “Christiana Riot,” which occurred in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, on September 11, a slaveowner, Edward Gorsuch, of Baltimore County, Maryland, attempted at gunpoint to retrieve several of his escaped slaves. In and around an isolated farmhouse, William Parker, a twenty-nine-year-old local black activist and himself a former fugitive slave from Maryland, led a crowd, some with pitchforks and some with guns, to defend the runaways. Parker had for several years led a self-protection society in Lancaster County that fought to rescue fugitive slaves from their pursuers. Gorsuch was shot dead in the melee in Christiana and his son badly wounded. Parker, astute and knowledgeable of Douglass’s work in helping fugitives into Canada, quickly led two of the desperate slaves, named Alexander Pinckney and Abraham Johnson, on a two-day, five-hundred-mile journey by foot, horse-drawn carriage, and train to Rochester.30

Fugitive slaves running through western New York frequently ended up on Douglass’s doorstep. Just as Parker and his charges arrived, and Anna fed and arranged sleeping quarters for them in the house, the news of the Christiana bloodshed arrived in Douglass’s hands via the telegraph and the New York newspapers. Great anxiety overtook the household, Douglass recalled. He wrote a short note to his neighbor Samuel Porter asking for help: “There are three men now at my house—who are in great peril. I am unwell. I need your advice. Please come at once.” Julia Griffiths too had been sick, she wrote on September 24 in a letter to Gerrit Smith, reporting recent “great excitement in our house” about the Christiana fugitives. Douglass and his small team acted decisively in this little corner of what was already widely called the Underground Railroad. “I dispatched my friend Miss Julia Griffiths to the landing three miles away on the Genesee River,” he wrote in Life and Times, “to ascertain if a steamer would leave that night for any port in Canada.” Douglass drove the three men in his “Democrat carriage” (a small three-seat buggy) to the landing, which is where he feared trouble from officers hot on their trail. He arrived with fifteen minutes to spare before departure. Douglass always remembered this episode with special pride and drama. “I remained on board till the order to haul in the gangplank,” wrote Douglass. “I shook hands with my friends, received from Parker the revolver that fell from the hand of Gorsuch when he died, presented now as a token of gratitude and a memento of the battle for liberty at Christiana, and I returned to my home with a sense of relief.”31 That gun remained a sacred talisman in the Douglass family.

When Parker and his small troupe reached Kingston and Toronto, they found black communities rather reticent to embrace them because news had spread of their deeds and that lawmen were in hot pursuit. Parker contrasted such self-protective fear among Canadian blacks, also largely fugitives, to the “self-sacrificing spirit of our Rochester colored brother [Douglass], who made haste to welcome us to his ample home.”32 In their brief encounter, brothers in arms, Douglass and Parker forged a bond of experience.

In Douglass’s own early account of the Christiana event, published in his paper on September 25, it was as if he had found the African American equivalent of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in the American Revolution. In Parker and Christiana he had a new character and event to exalt. His “Freedom’s Battle at Christiana” is at once a brilliant piece of propaganda, astute reporting, and a mythic testament designed to give the resistance movement bold inspiration. Douglass mocked the proslavery public that seemed shocked that “hunted men should fight with the biped bloodhounds” and kill them out of self-defense. “Didn’t they know that slavery, not freedom, is their natural condition? Didn’t they know that their legs, arms, eyes, hands, and heads were the rightful property of the white men who claimed them?” He portrayed Christiana and the whole universe of dread and violence caused by the Fugitive Slave Act as a kind of theater of the absurd. Americans did not hunt “fox, wolf, and the bear” anymore. Hunting men, said Douglass, had become the official “choice-game, the peculiar game of this free and Christian country.” Such hunters had stepped out of the natural “orbit” of humanity and therefore had “no right to live.” In his re-creation of the Christiana affair, based apparently on his brief interviews with Parker and the other two fugitives, Douglass fashioned a dramatic dialogue between Gorsuch and Parker in their lengthy “parley” at the farmhouse. Gorsuch demanded his “property,” and Parker spoke as from a natural-rights treatise saying, “There is no property here but what belongs to me. . . . I own every trunk chair or article of furniture.” Parker lectures Gorsuch about how “it is a sin to own men,” as Gorsuch’s son fires the first shot, which misses Parker.33

Douglass converted the entire story into an argument for natural rights, especially after the news came that some thirty blacks and two whites were captured and to be indicted for “treason” in the case. “The basis of allegiance is protection,” wrote Douglass. The only law a slave could acknowledge was the “law of nature.” “In the light of the law, a slave can no more commit treason than a horse or an ox can commit treason.” Then he all but thanked the legal authorities of Pennsylvania for the charge of treason against the Christiana rioters because, he said, “it admits our manhood.”34 Douglass always knew when he had irony, if not the law, on his side.

• • •

A relative lull ensued in anti–Fugitive Slave Act rescues during 1852 and 1853. But the furor resumed with new intensity in the spring of 1854 in Boston with the seizure, trial, and return to Virginia of a fugitive named Anthony Burns. The Franklin Pierce administration in Washington, as well as Massachusetts state officials, especially Democrats, made a test case of Burns as they determined to enforce the Act of 1850. Before Burns was finally marched down Boston streets that were draped in mourning by the black community and guarded by several thousand federal troops, a major effort was made to rescue him, resulting in the death of one deputy US marshal, James Batchelder, a local truckman hired as a guard. Although the Burns case was a short-term failure for abolitionism, it became a cause célèbre across the country. During 1852–53 Douglass had kept up a steady drumbeat of attacks on the Fugitive Slave Act. At the Free Soil Party convention in August 1852 he called for “half a dozen or more dead kidnappers carried down South” to keep slaveholders’ “rapacity in check.” He wanted body counts, and lest the “lines of eternal justice” be “obliterated,” he called for “deepening their traces with the blood of tyrants.” America had become polarized by the fugitive-slave crisis; even some Garrisonians began to talk of violence. “The line between freedom and slavery in this country is tightly drawn,” Douglass argued by early 1852, “and the combatants on either side . . . fight hand to hand. . . . There is no neutral ground here for any man.”35 He became his own kind of self-styled war propagandist long before 1861.

In the wake of the Burns case Douglass penned a much-discussed editorial, “Is It Right and Wise to Kill a Kidnapper?” He had been answering this question affirmatively for years, but here he claimed the high ground of “moral philosophy.” The natural law of self-defense against aggressors or kidnappers, Douglass argued, carried the same power as the “law of gravitation.” But this was about human actions and not gravitational pull. So when “monsters” deliberately violate the liberty of a fellow human, other men are justified in killing them if necessary. Further, he contended, if government failed to protect the “just rights of an individual man,” then “his friends” may exercise “any right” to defend him.36

Douglass dove foursquare into American racial reality. He felt no sympathy for the slain Boston man who got in the way, nor even for his widow. By becoming the hired “bloodhound” Batchelder made “himself the common enemy of mankind, and his slaughter was as innocent, in the sight of God, as would be the slaughter of a ravenous wolf in the act of throttling an infant. We hold that he had forfeited his right to live, and that his death was necessary.” But Douglass went even further. This was a public death and was not done as a last resort; rather, it emerges in Douglass’s logic as a first resort, an aggressive use of violence to make a political statement. He argued that the killing in defense of Burns would lift the label of “submission” from the heads of black people. They needed this deed for their self-respect. An image in the American mind, Douglass asserted, had to be destroyed—that of fugitives who “quietly cross their hands, adjust their ankles to be chained, and march off unhesitatingly to the hell of slavery.” In the public mind, he said, such behavior was judged “their normal condition.” But no longer. “This reproach must be wiped out, and nothing short of resistance on the part of colored men, can wipe it out. Every slaveholder who meets a bloody death . . . is an argument in favor of the manhood of our race. Resistance is, therefore, wise as well as just.”37 Douglass harbored no moral ambivalence about violence now; he demanded dead slave catchers as recognition and revitalization of black humanity.

Douglass’s harsh, masculine case became both primal and philosophical, bursting from his embittered heart. In the fugitive-slave crisis, Douglass counseled killing kidnappers, and slaveholders generally, because it enhanced the self-respect and “manhood” of his people. His was a position of a gendered moral quicksand, but also astute, political revolutionary violence. He had once fought Covey in a last resort for self-respect. Now he advocated a much larger violence, with greater political meaning, and as a first resort. Douglass now believed in killing slave catchers and slaveholders; the means to such an end were the strategic and moral challenge. He had long laid out deeper and older justifications for such violence than he offered in the 1854 editorial. In many speeches he had limned the old prophets as his steady keel in these troubled waters. Over and over again in 1853 and 1854, Douglass used Isaiah 57:20–21 to make his case: “But the wicked are like the troubled sea, when it cannot rest, whose waters cast up mire and dirt. There is no peace, said my God, to the wicked.” Douglass made this holy writ his own kind of oracle in New York in May 1853, in a speech entitled “No Peace for the Slaveholder.” The machinations of the Slave Power, he contended, were “done to give peace to slavery. That cannot be done. Peace to the slaveholder! He can have no peace. ‘No peace to the wicked, saith my God.’ ” For Douglass this was a matter of faith and political motivation. The nation may act so “our southern brethren may have peace,” he told a Manchester, New Hampshire, audience in January 1854. But “they have undertaken to do what God Almighty has declared cannot be done.”38 The violent imagination desperately needed authority and precedent. And a new prophet dearly needed the old ones.

• • •

Sometime in February 1853 Douglass paid a visit to Andover, Massachusetts, at the home of Harriet Beecher Stowe. In an extraordinary column, “A Day and a Night in ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ ” the editor wrote of the encounter as a magical experience. Not yet a year in circulation, Stowe’s book had reached “the universal soul of humanity,” Douglass said. He crafted an extraordinary portrait of Stowe. She was at first impression an “ordinary” woman, but in conversation she exhibited a “splendid genius,” a “keen and quiet wit,” and an “exalted sense of justice.” Douglass had many models as a writer and orator; but he may have found a new one. With Stowe, he observed, “the words are . . . subordinate to the thought—not the thought to the words. You listen to her rather than to her language.” As she talked, he remembered her eyes flashing with “especial brilliance.” The inspiration, Douglass said, was “not unlike that experienced when contemplating the ocean waves upon the velvet strand.” As though practicing his own fictional chops, the editor continued, “You see them silently forming—rising—rolling and increasing in speed, till, all at once they are gloriously capped in sparkling beauty.” Douglass could hardly contain his “reverence,” comparing Stowe to Burns and Shakespeare, “the favored ones of earth.” He left feeling assured that Mrs. Stowe was his “friend and benefactress.” He had visited, in part, to discuss her possible support for the “elevation” of free blacks.39

Douglass sat down at his desk in early spring 1853 to write a work of short fiction, “The Heroic Slave,” which reflected his personal state of mind, his evolving ideas on violence, and the national crisis he sought to influence. The story, first published in his newspaper in March, re-created a five-year period in the life of Madison Washington, the slave who led a successful revolt aboard the domestic slave-trading ship Creole in 1841 and sailed it into Nassau harbor, a British port, resulting in the liberation of the more than three dozen slaves.

Douglass had long addressed the story of Washington and the Creole mutiny in speeches in the late 1840s in Britain and America. He had kept its memory alive as a historical precedent for slave rebellion and as a rhetorical weapon. He did so especially in New York in April 1849 to twelve hundred blacks at the Shiloh Presbyterian Church, where he told Washington’s tale in imaginative terms to the delight and laughter of his audience. In such speeches Douglass tried out some scenes that ended up in the novella, although much of the 1849 effort was devoted to the irony of monarchial Britain freeing self-liberated slaves from “free, democratic” America; he especially relished the image of the former bondmen escorted off the ship in Nassau by “a platoon of black soldiers.” He reserved a special sarcasm for how this American “property” emerged as human beings from the clutches of outraged US senators such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, and the secretary of state, Daniel Webster, who issued formal protests to the British. Unmistakably, Douglass left those public audiences with a dire warning: “There are more Madison Washingtons in the South, and the time may not be distant when the whole South will present again a scene something similar to the deck of the Creole.”40

Literary scholars have suggested many reasons why Douglass turned to fiction, although any explanation begins with his obligation to produce something original for Julia Griffiths’s book, Autographs for Freedom. The turn to fiction to expose the full danger of the fugitive-slave crisis was also a logical progression in Douglass’s evolution as a man of words; he had mastered oratory, achieved fame with autobiography, and now independently engaged the world of journalism. Fiction was the next form, and it offered him some artistic range that even his most creative oratory had not. As critics Shelley Fisher Fishkin and Carla Peterson have shown, Douglass could drop his ever-present I pronoun and adopt the more versatile third-person narrator as the voice of his polemic. He gave a profound voice to the slave rebel, in the person of Madison Washington, for an audience that could see such figures only as a dangerous lot. Robert Stepto effectively points to how fiction enhanced Douglass’s brilliance in using contradiction and irony. Douglass also found in Washington’s story a striking means to give another “salute” to British abolitionists, and especially to declare in storytelling just how much he had broken with Garrisonian moral suasion and pacifism.41

Literary historian Robert Levine, moreover, argues that “The Heroic Slave,” with its depictions of a noble, stunningly intelligent, yet violent slave rebel, was Douglass’s critique of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (only a year into its enormous success), as well as a potential allegory about the abolitionist’s relationship with Harriet Beecher Stowe herself. Washington prays effusively in the novella for his liberation, yet in the end does not rely only on God for freedom. He is beaten savagely like Uncle Tom, but is no Jesus figure. He is the militant, praying rebel, willing to use a “temperate revolutionary” violence, a mixture perhaps of Uncle Tom and George Harris. Douglass did express ambivalence about Stowe’s novel in turning to fiction, although he never stopped honoring Stowe herself.42 He admired her deeply and loved the impact of her book, even as he invented alternative characters.

Douglass’s increasingly strident advocacy of violent resistance against the terror practiced against fugitive slaves found an interesting outlet in Washington’s story. “The Heroic Slave” allowed Douglass, as one critic has argued, to create “a new edition of himself.” He had always portrayed himself as a reluctant fighter, a rebel in self-defense only, the means directed to the end of natural, God-given liberty and self-possession. Douglass was primarily a man of intellect, not brawn, words, not military action. But in Washington he created a character who was a noble combination of all those elements. The plot of the story breaks down at times, and some lame transitions mar its literary quality. Douglass relies, not surprisingly, on a narrator, on speech-making in long soliloquies rather than sustained character development. But within the sentimental literary conventions of the time, it is not difficult to see why many readers, especially if they had read Douglass’s and other slave narratives, would have found the story moving and well paced.43

When Mr. Listwell, a traveling Ohioan, happens upon the desperate Madison out in the woods, praying and contemplating escape as he also fears leaving his wife and children, we encounter a description of a fabulously heroic figure who represents every element of nineteenth-century manliness, except that of freedom and self-possession. Madison is a “manly form.” He is “tall, symmetrical, round, and strong.” He combined the “strength of a lion” and a “lion’s elasticity.” His “torn sleeves” exposed “arms like polished iron.” Douglass’s Madison was a man of transformative eloquence as well as action. His “heart-touching narrations of his own personal sufferings” to the silent forest, overheard by Listwell, convert the Ohioan immediately to radical abolitionism. And in Listwell (“listens—well”) Douglass created a striking character, a stand-in for all the Yankee white abolitionists he had known who had, in their best instincts, helped slaves such as himself to freedom, knowledge, and self-realization.44 In Mr. Listwell he was trying to tell the Garrisonians something about the role he [Douglass] preferred for them, instead of the one he had come to expect from them.

“The Heroic Slave” contains some striking dialogue and effective narration, a story of how the Underground Railroad did sometimes work for fugitives heading to Canada, and especially of a dilapidated, gothic Virginia tavern, occupied largely by drunken “loafers,” where Listwell once again encounters Madison trapped in a slave coffle trudging in chains to Richmond for sale. That tavern, its foreboding, decaying setting, and the dialogues between the loafer and Listwell about slave trading, are Douglass’s metaphors for the South and for the nation’s predicament with slavery. We never actually see the blood and killing on the deck of the ship, a consideration for the white readers, but witness Madison’s magnanimity in saving the first mate’s life, as he also converts him to the realization that with this slave rebel he is “in the presence of a superior man.”45 Madison Washington conquers his foes with courage, character, and with the power of the word. He also conquers with the sword as he must. But more restrained than in his speeches and editorials about the need for dead slaveholders or slave catchers, Douglass spares his readers the pools of blood on the deck of the Creole. Fiction seems to have allowed for artistic control over the rage within.

Would that Douglass had attempted more works of fiction; he possessed a stunning ability with narrative. By the force of his will, from constant discipline, and from the help of friends, especially Julia Griffiths, he had emerged by the mid-1850s as a versatile and accomplished writer, one deserving a place eventually in that era’s literary American renaissance. By late 1854 and early 1855 he took to his desk for even longer stints of time to revise his original Narrative, to remake himself once again in print, and produced My Bondage and My Freedom, arguably the greatest of all slave narratives. This second autobiography would be at once more revealing and more revolutionary than the first because more political. Douglass was a great storyteller; but now he courted yet new dimensions of personal and public conflict as he plunged into the art of politics. It was one thing to try to be the prophet in Babylon, but quite another thing to be a prophet in party politics.