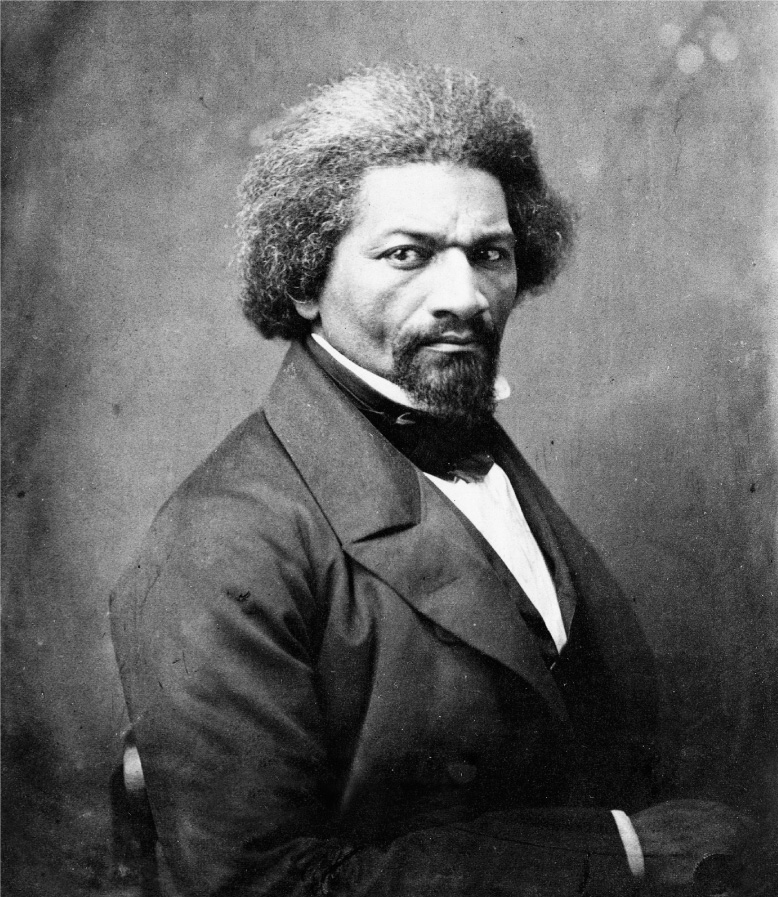

Frederick Douglass, c. 1858. Print from a lost daguerreotype.

John Brown’s raid upon Harpers Ferry was all his own. . . . His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light, his was as the burning sun. I could speak for the slave. John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave, John Brown could die for the slave.

—FREDERICK DOUGLASS, HARPERS FERRY, 1881

John Brown was charismatic, inspiring, confounding, courageous, mysterious, intimidating, given to religious zealotry, and even at times a bit boring. But he and his deeds were unforgettable. Before Frederick Douglass first met Brown in 1847, or possibly early 1848, in Springfield, Massachusetts, Douglass had heard about him, especially from other black abolitionists, who “when speaking of him, their voices would lower to a whisper.”1 A touch of legend, creatively crafted in Life and Times, infused Douglass’s extraordinary remembrance of his relationship with the leader of the Harpers Ferry raid.

In real time, Douglass’s first recorded description of Brown, written in the North Star in February 1848 after returning from a lecture tour, conforms to later remembrances. Brown was among the key people Douglass met in Springfield after delivering a lecture that the local paper deemed objectionable because the former fugitive had “stigmatized the whole country” as a “slave hunting community.” Whether Brown attended the lecture is not clear, but in what Douglass called a “private interview” Brown left a lasting impression on Douglass. “Mr. Brown is one of the most earnest and interesting men that I have met,” said the orator. Although white, Brown came across in “sympathy a black man, and is deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.”2

Brown ran a wool business in Springfield out of a large store and warehouse, one of many such enterprises as a merchant, a tanner, and a farmer that he launched over three decades, almost all of which failed and left his huge family poor. During this first encounter, Douglass spent the night with Brown’s family in what Douglass remembered as their “Spartan” house. So large and controversial had Brown grown in national memory, that in his recollection in Life and Times Douglass strove for unusual detail. He remembered the simple ingredients served at dinner, the walls “innocent of paint,” the table “unmistakably of pine and of the plainest workmanship.” Everything about John Brown and his house reflected, said Douglass, the “stern truth, solid purpose, and rigid economy” of the man. Brown “fulfilled St. Paul’s idea of the head of the family,” Douglass observed, his wife and children treating him “with reverence.” As though fashioning the precise characteristics of a fictional character, Douglass described Brown’s facial features, his hair, his height and weight, even the color of his eyes, which in “conversation . . . were full of light and fire.” Brown walked with “a long, springing race-horse step, absorbed by his own reflections.” Here, rising out from the “whispers,” Douglass announced was “Captain John Brown . . . one of the most marked characters and greatest heroes known to American fame.”3

But a great deal of troubled reality lay beneath Douglass’s literary reinvention of 1881. The twelve-year relationship between Douglass and Brown is one good lens through which to view both men. During the 1850s, as Douglass moved toward at least open support of violent means, the two abolitionists spent many hours and days in each other’s company. As Douglass came within John Brown’s orbit of religious fervor and theories of violent resistance, Douglass listened even as he was sometimes repelled.

Born in Torrington, Connecticut, in 1800, Brown grew up primarily on the Western Reserve in Hudson, Ohio. His father, Owen, bestowed a staunch Calvinism in his son. Brown’s memories of childhood were layered with dislocation and loss, especially that of his mother, who died when the boy was only eight. His father married three times and sired sixteen children, a pattern John eventually more than matched with two wives and twenty children, many of whom did not reach adulthood. In John’s youth, the Browns’ household in Ohio funneled fugitive slaves on to liberty in the region or in Canada; Owen was a devout Christian abolitionist. By the time Douglass and John Brown met, and for the duration of their relationship, among the sensibilities and experiences that they shared were a relative lack of formal education, the humiliations and necessities of begging for money, an Atlantic crossing to Liverpool on the Cambria (at separate times), a Bible-inspired sense that history could undergo apocalyptic change, and a passionate hatred of slavery as a system at war with humanity.4

At that first meeting in Springfield, Brown and Douglass conversed long into the night at a table in candlelight. Brown unfolded a large map of the United States and pointed to the Alleghenies. “These mountains,” Douglass recalled Brown asserting, “are the basis of my plan. God has given the strength of the hills to freedom; they were placed here for the emancipation of the Negro race.” For many years to come, decoding just what the elements of Brown’s “plan” were became a beguiling preoccupation for Douglass and others. On that night in Springfield, he was enthralled but skeptical; he never claimed to know with any certainty the purpose of the Virginia mountains, morally or geologically. Brown, however, imagined them “full of natural forts” and “good hiding places.” Beginning with only twenty-five trained men, he would “run off the slaves in large numbers” in at least one Virginia county. Somehow in these mountain hideaways they would fight off the inevitable force that would assemble in counterattack, and many of the local slaves would join their force. The “true object,” Douglass gleaned, seemed to be destroying “the money value of slave property.” That aim Douglass understood. But then he pushed back with questions Brown could answer only in moralistic, not strategic, terms. How would he “support” his men? Douglass asked. What would Brown do when surrounded by the “bloodhounds” of the Slave Power’s police state when roused? Brown thought he could whip them, but if he could not and was killed in such guerrilla action, “he had no better use for his life than to lay it down in the cause of the slave.”5 In this reinvented conversation, Douglass expressed a harsh truth about Brown. The old warrior worked passionately for years on a plan that in the end may have represented a personal desire to sacrifice for the slaves more than a genuine strategy for revolution.

• • •

In these years Douglass looked anxiously for a logic in violence. The problem with Brown was that he could never be completely squared with rationality. But as we have seen, in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act or Dred Scott, logic was no longer the weapon of choice for a radical abolitionist. Douglass admitted that the more contact he had with Brown, “my utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man’s strong impressions.” Douglass and Brown continued to correspond through the early 1850s, and they eventually met on many more occasions. At least as early as 1851 the two exchanged letters making sure Brown received Douglass’s paper. And in 1854, after Brown had moved to Akron, Ohio, he wrote an extraordinary epistle to Douglass in the voice of an Old Testament prophet chastising the evils of American leaders and their poisoned institutions. It was as though Brown wanted to join Douglass in condemning the Slave Power, but to do so with even more biblical rage. Worried about the fate of the American republic, Brown had no doubt about what stood in its path: the proslavery “extreme wickedness” of political and religious leadership at all levels, even the “marshals, sheriffs, constables and policemen.”6

We do not have Douglass’s direct response to this letter, but what he read in Brown’s condemnations of American perfidy was a denunciation, even beyond higher-law doctrine, that left only violence as an option. American leadership was taking the country into “anarchy in all its horrid forms,” Brown argued. Therefore, he had a ready answer: “What punishment ever inflicted by man or even threated by God, can be too severe for those whose influence is a thousand times more malignant than the atmosphere of the deadly Upas—for those who hate the right and the Most High.” To Brown, God governed the universe and its man-made nations. Hence, the only alternative for the righteous was to destroy such “fiends clothed in human form.” Brown trusted Douglass’s knowledge of Scripture as he poured forth passages from the Old and New Testaments. To a degree Brown and Douglass shared a biblical grounding. The real laws of the United States for Brown were God’s commands. “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped. . . . Thou shalt not oppress him,” he recited from Deuteronomy in his letter to Douglass. From Matthew, Brown revisited the famous command “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them; for this is the law and the prophets.” And in Nehemiah he found his indictment of rulers who had forsaken God’s law: “Remember them, O my God, because they have defiled the priesthood.” Nehemiah had “smote” and “cleansed” when necessary the wayward Israelites. As Brown wrote to Douglass in early 1854, even before the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Brown seemed lonely and mired in a deep Christian despair over the “abominably wicked . . . laws” of the country. But he fully expected a reckoning to come. “I am too destitute of words to express the tithe of what I feel,” Brown concluded, as he begged Douglass to convey his appeal in “suitable language” to a larger world.7

By and large, Douglass did just that. He admired and used the Hebrew prophets, and Brown not only looked and talked like one, he seemed willing to challenge or destroy the wicked Jerusalem. In Life and Times, Douglass confessed that he never felt in the “presence of a stronger religious influence” than in the company of John Brown. Although Douglass honored human law more, perhaps the sensibility that he and Brown shared most in the long run was a millennial and apocalyptic sense of history, drawn from the old stories of the prophets and from the zeitgeist of antebellum America. In that era millennialist thought was a cluster of religious and secular ideas forged into a kind of national creed. In its more hopeful mode, it held that Christ would have a Second Coming in the “new Israel” of America, or at least that the country possessed a mission as a “redeemer nation” destined to perform a special role in history. Millennialism was an outlook on history, a disposition about human nature, a belief that America was a place where mankind had been given a second chance; and above all, that God governed history and chose the moments of transformation. A nation of Protestants could interpret events as steps in its providential destiny. The darker side of millennialism exposed the burden of chosenness; an eschatological expectation of God’s wrath and destruction meant that people must constantly prepare for a break in time and new beginnings.8

Both Douglass and Brown shared this vision. Sterner and bleaker, Brown’s millennialism manifested in daily devotions and instructions to his children. Brown’s son Salmon remembered his father’s strict Sabbath observance: “Sunday evenings he would gather the family and hired help . . . and have the Ten Commandments and the Catechism repeated. Sometimes he would preach a regular sermon. . . . Besides we had prayers morning and night of every day, with Bible reading, all standing during prayer, father himself leaning on a chair, upreared on the forward legs, the old-fashioned Presbyterian way.” Brown’s faith was rooted in a deeply personal concern about sin, his own and that of others, especially his children. “He constantly expostulated with us,” said Salmon, “and in letters when away. His expressed hope was ‘that ye sin not, that you form no foolish attachments, that you be not a ‘companion to fools.’ ”9

Brown was often hardest on himself, on his own profound need for atonement. His record of business failures, his struggle to provide meager sustenance to his brood as he lost more than one farm, and his imprisonment for debt in the wake of the panic of 1837 left him many inner demons. Writing to all his children in late 1852, he worried that they had lost the faith he had instilled in them, even as he blamed himself. He admitted to “little, very little to cheer” and hoped that his “family may understand that this world is not the Home of man.” He urged his sons and daughters not to reflect on how their father had “wandered from the Road,” but to pray to God for their own “thorough conversion from sin” and to stay “steadfast in his ways through the very short season of trial you will have to pass.” In the midst of such religious affliction, Brown ended the letter worried about whether the family could afford to “pay for Douglas paper.” In a remarkable letter to his eldest son, John Jr., in 1853, Brown expressed “pain and sorrow” at the young man’s loss of faith. Then John Sr. drew upon passages from the first five books of the Old Testament to warn his erring son with the words of Moses, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, and Samuel not to fall into the “same disposition in Israel to backslide.” Brown’s sons were devoted abolitionists; they followed their father for their own reasons, perhaps least of all because he had used Joshua to instruct them. John Jr. later experienced a mental breakdown in Kansas in 1856, captured, beaten, and imprisoned after fighting as a guerrilla warrior at his father’s side. Another son, Frederick, was killed in the Kansas war. John Brown’s personal holy war on slavery became an extended family disaster.10

Douglass, on the other hand, was a father deeply concerned with his children’s literacy and education, but we do not know as much about his concern for their religious temperaments. He seems to have worried more about their writing skills than their faith. “I know this is not as good writing as you would like to see,” wrote his fifteen-year-old son Charles in 1860, “but I am in haste so good night.”11

In these years, Douglass’s millennialism and his religious faith were a set of root values layered throughout his oratory and his writing. He arrived at his spiritual understanding of history through his lifelong informal theological means—reading the Bible and a good deal of history, and especially by his years of rhetorical engagement on abolitionist platforms, listening to and arguing with Garrison, Phillips, Gerrit Smith, McCune Smith, Remond, Delany, Abby Kelley, and others. Douglass’s millennialism was forward-looking and activist. Waiting for the “jubilee” of black emancipation and the fulfillment of America’s national destiny required patience, but also struggle; it demanded faith, and suffering.

Douglass played the prophetic role of the “suffering servant” with zeal. His famous statement about agitation, delivered in a speech in 1857, has stood the test of time and numerous protest ideologies: “If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning. This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” Those were what McCune Smith had called Douglass’s “work-able, do-able words” for the ages.12

In his analysis of the Slave Power, Douglass accepted political and moral loss as the price of an inevitable progress. Sometimes his rhetoric could seem driven by a vague moral determinism. The enemies, slavery and freedom, were irreconcilable, he wrote in 1855, but freedom must triumph because it had the “laws which govern the moral universe” on its side. A collision between these two enemy forces “must come,” Douglass maintained, “as sure as the laws of God cannot be trampled upon with impunity.”13 Millennialists had a peculiarly persistent need for that word “must.” It kept them moving through the thickets of uncertainty.

But for Douglass millennial symbolism was not merely a rhetorical device to sustain collective hope; it was a real source of faith. He wanted his thousand black listeners to see “a celebration of the American jubilee,” Douglass declared in Canandaigua, New York, in 1857. “That jubilee will come. You and I may not live to see it; but . . . God reigns, and slavery must yet fall; unless the devil is more potent than the Almighty; unless sin is stronger than righteousness, slavery must perish.” History possessed a trajectory, not easily discerned. “There was something God-like” in the British decree of emancipation in the West Indies in the 1830s, Douglass proclaimed. He knew that British emancipation was more complex than spiritual imagery alone could convey, but he could not resist calling the event a “wondrous transformation” and a “bolt from the moral sky.” He called on African Americans to see West Indian emancipation as “a city upon a hill” to light the way toward their own new history.14 Such faith was difficult to sustain after the Dred Scott decision.

In a letter to a Scottish antislavery society, with which Julia Griffiths now worked to raise money for Douglass’s paper, the editor acknowledged dark portents hanging over the abolitionist cause. Then he gave his correspondent a good dose of millennial medicine: “I am now at work less under the influences or inspiration of hope, than the settled assurances of faith in God—and the ultimate triumph of Righteousness in the world. The cause of the slaves is a righteous and humane one. . . . Though long delayed, it will triumph at last.”15 Torn at times between warring options, Douglass knew he must travel by faith as much as by sight.

But he would also have his fellow blacks see and act as well as believe in their path to liberation, and thus perhaps his sustained interest in Brown’s revolutionary schemes. Emancipation in the British empire gave Douglass a grand historical precedent and a reason to issue a call to arms in his own country. Americans were good at “fast days and fourth of Julys,” Douglass said, but their “sequel” never showed anything but “men whose hearts are crammed with arrogancy, pride, and hate.” Then, characteristically, Douglass found his firm footing and his story in Isaiah 58: “We have bowed down our heads as a bulrush, and have spread sackcloth and ashes under us.” Isaiah had warned so poignantly against false fasting. The House of Jacob fasted, but in the end “seest not” and “takest no knowledge.” In his own best King James language, Douglass argued just the same for Americans who could not or would not learn from the past. British emancipation had been an act, he believed, not about “commerce, but conscience,” a “spiritual triumph,” and a “product of the soul.” Rewriting Isaiah nearly word for word for a new century and place, Douglass declared his countrymen incapable of what the British had created: “a chosen fast of the Living God . . . a day in which the bands of wickedness were loosed; the heavy burdens undone; the oppressed let go free; every yoke broken; the poor that were cast out of the house brought in; and men no longer hiding themselves from their own flesh.”16 Instead, Americans were just so many marsh plants sagging over silently in the swamp.

To Douglass, though, history was both warning and inspiration. He also used the model of West Indian emancipation to remind audiences that Jamaican slaves had rebelled many times on their road to a parliamentary edict of their freedom. He reminded his black audience in upstate New York of McCune Smith’s overt plea in 1856 that they [blacks] not wait for liberty to be given, as in the British empire, and instead celebrate their own heroes such as Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner. As he so often did in the 1850s, Douglass quoted the passage from Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, “Who would be free, themselves must strike the first blow.” Then, rather stunningly, he reminded his auditors of the black heroes who had risked death rather than endure slavery—Margaret Garner’s infanticide, Madison Washington of the Creole shipboard rebellion, Parker and the Christiana rioters, Joseph Cinqué of the Amistad mutiny. Douglass stressed how much insurrection had ultimately influenced British colonial planters to accept abolition and awakened the guilty fears of white Southerners when “General [Nat] Turner kindled the fires of insurrection in Southampton.” Douglass was ready to probe the dark “rebellious disposition of the slaves” if only he could find someone with a plan he could trust.17

• • •

During the decade before Harpers Ferry, Douglass sustained an abiding interest in aiding Brown’s crusade, less perhaps on strategic grounds than because of the white radical’s demonstrable commitment to racial equality. Although their temperaments differed markedly, their face-to-face encounters, correspondence, and shared interest in the possibilities of violence sustained a friendship. Many black abolitionists would eventually honor Brown’s racial openness after he died a martyr’s death; at the heart of his immediate legacy, after all, was the idea that he was the white man who died to set black people free.18

In 1848, shortly after his first meeting with Douglass, Brown published a satirical essay, “Sambo’s Mistakes,” in the black newspaper Ram’s Horn. Written in the voice of a black man who needs to confess his misdeeds of apathy, materialism, and sloth, the piece invoked many stereotypes about Northern free blacks. Instead of taking advantage of education, this Sambo spent his time “devouring silly novels & other miserable trash.” Instead of saving money to buy a good farm, he preferred “chewing & smoking tobacco.” Rather than attaining “character & influence among men,” this ne’er-do-well was “obliged to travel about in search of employment as a hostler shoe black & fiddler.” He could never practice self-denial and loved his “Chains, Finger rings, Breast Pins.” And worst, he confessed to failing as “a citizen, a husband, a father, a brother, a neighbour.”19 Witty but bizarre, this awkwardly written essay demonstrated not only a Puritanical obsession with the foibles of others, but a direct attack on the lack of self-reliance among blacks. It could be read as misguided racial paternalism, as ironic self-revelatory guilt, or as a righteous chastisement of a disorganized black community that needed upbraiding.

With McCune Smith, Douglass had long demanded greater black self-improvement initiatives and felt frustrated by an apathy he found among free blacks. He could “stand the insults . . . and slanders of the known haters” of his people. He welcomed them as a “natural incident of the war.” But what exasperated him was the “listless indifference” hanging over so many struggling blacks “who should be all on fire.” Hence, not only was Douglass impressed with Brown’s egalitarianism, but with his direct efforts to help raise black aspirations. In 1846 Gerrit Smith purchased a huge tract of 120,000 acres of land in upstate New York with the intent of granting it to urban free blacks so they could become independent landowning farmers and thus qualify to vote under that state’s suffrage law. Although the environment was harsh, some blacks took advantage of the utopian plan; and in the spring of 1849 Brown, with his wife, Mary, and five children, joined them in North Elba. There Brown for a while devoted himself to living among “these poor despised Africans,” as he put it, in settlements known as Timbucto. Brown employed a free black man named Thomas Jefferson as well as a fugitive slave from Florida named Cyrus. Blacks often took meals with the Browns at their farmhouse. Though as poor as the winters were cold, Brown dispensed occasional barrels of pork and flour to his neighbors as well as a good deal of advice about religion, personal conduct, and resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act.20

Douglass was amply aware of Brown’s antiracist venture in North Elba; Gerrit Smith had granted the Rochesterite a piece of land (which he never occupied) and did the same for most other black abolitionists. This kind of pioneering agricultural activism was never Douglass’s sphere, but he eagerly welcomed Smith’s uplift philanthropy among blacks. The sentiments of “Sambo’s Mistakes” appeared in many of Douglass’s editorials and speeches, some of which Brown read in the former slave’s paper. Whether from the backbreaking exertions of farmers on that mountain terrain of North Elba, or the literary and organizational leadership of black intellectuals, Douglass believed, as he stated in 1855, that “every day brings evidence . . . THAT OUR ELEVATION AS A RACE IS ALMOST WHOLLY DEPENDENT UPON OUR OWN EXERTIONS. If we are ever elevated, our elevation will be accomplished through our own instrumentality.” He eagerly wanted blacks to take their fate into their own hands. “Nothing is more humiliating,” Douglass smugly declared in 1857, than his own people’s apathy.21 He could only be moved and glad that a Gerrit Smith and a John Brown wished so sincerely to lend their lives to the quest for equality. But blacks could not wait for their white patrons.

To black audiences Douglass could preach as stern a brand of conservative self-improvement as any black voice of his era. In rhetorical moves representative of a brand of black nationalism, Douglass often turned attacks on white racism into angry rebukes of black lethargy. In an 1855 speech at Shiloh Presbyterian Church in New York to a mixed audience, Douglass, with McCune Smith chairing the meeting, wondered aloud about how difficult it was to address certain sensitive issues among blacks in front of whites. Blacks, Douglass said, too often provided a “spectacle” for all the world to watch in its desire to measure the “heights of civilization.” Douglass admitted that the larger world constantly asked, are blacks “like other men?” Could the “negro do without a master,” can he rise from “ignorance to intelligence,” or “disorder to order?” These questions could not “be answered by the white race.” They were “peculiarly the duties of the colored people.” And blacks’ “doubt among ourselves” stood in the way and caused Douglass, he confessed, to “blush” and fall into “gloomy thoughts.” His people must “show them” (whites) by becoming “skillful architects, profound thinkers, originators and discoverers of ideas.” They must produce their own Webster, Clay, and Calhoun.22

Then, as Douglass marched through this stern message, a group of “colored gals” walked into the sanctuary, distracting and annoying the orator, who stopped to upbraid them for not being “punctual.” Regaining his composure, Douglass gave a vigorous appeal for violent resistance to slave catchers. “Fear inculcates respect,” he proclaimed. “I would rather see insurrection for the next six months in the South than that slavery should exist there for [the] next six years.” He left his Shiloh audience laughing with jokes about how whites automatically think of blacks as drunk or lazy and ended by singing an abolition ballad to the tune of “I’ll Never Get Drunk Again.”23 Brown would have wholeheartedly agreed with every gesture, except possibly the jokes.

Similarly, three years later, at the same church, but to a largely black audience gathered to protest historic discrimination on the Sixth Avenue Railroad in New York, Douglass blasted the “spirit of caste” that robbed his people of every kind of civil right. But worst of all, now one year in the wake of Dred Scott, he feared that the “emancipated colored man” risked having “burned into his very soul the brand of inferiority.” He openly worried in front of his fellow blacks that an impression had settled upon them implying that “we ourselves are unconcerned and even contented with our condition.” Douglass confronted his auditors harshly: “I detest the slaveholder, and almost equally detest a contented slave. They are both enemies of freedom.” With no jokes to soothe the message, he left the 1858 protest rally with the warning that “oppression . . . deadens sensibility in its victims.” The only recourse was to sustain faith not in law but in “ourselves.”24 Such fierce appeals for self-reliance, mixed with demands for violent resistance, in the late 1850s made for a potent if toxic brew of confusion, rage, and bloodlust.

• • •

As Douglass tried to find firm footing with these issues and with his emerging relationship with Brown, another kind of confusion walked forthrightly into his life. Seeking permission to translate and publish My Bondage and My Freedom in German, Ottilie Assing first came to visit Douglass in Rochester in the summer of 1856. Born in 1819 in Hamburg to a physician-poet father and a mother who was a teacher and Romantic poet, Assing had veered from one kind of idealistic and romantic cause to another until, in personal frustration and desperate for independence, she moved to America in 1852 to pursue a new career as a journalist. Emotionally volatile (the survivor of at least one suicide attempt with a dagger she took to her chest when she was twenty-three), a freethinking atheist, and a devotee of Alexander von Humboldt’s ideas about human equality, Assing soon saw that the most compelling issues in her adopted America were race and slavery. As a German romantic she was always in search of the hero in history, the maker of new nations, new ideas, and new times. By attending antislavery meetings in New York after she took up residence among other German émigrés across the Hudson River in New Jersey, Assing began to discover candidates for her ideal hero. First there was Wendell Phillips, whom she saw speak and found enthralling at the annual gathering of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1854. Then for a while she became fascinated with James Pennington, the minister of Shiloh Presbyterian Church in New York; Assing wrote a long, unwieldy essay on the black preacher and translated some of his narrative, The Fugitive Blacksmith, until she lost interest, possibly because of a fundamental distaste for religion and the black church.25

The only account we have of Assing and Douglass’s first meeting is Assing’s own, which, in her breathless style, she self-servingly included in her introduction to the German edition of Bondage and Freedom. She must have come to Rochester all but unannounced since she first stopped at the office of the North Star only to discover that the editor was still at home. As a fellow journalist, she had come to interview Douglass. So as directed, Assing walked the more than two miles to South Avenue to find the editor’s homestead. She found a “handsome villa, surrounded by a large garden . . . situated on a hill overlooking a charming landscape.” But she reserved most of her Vorrede to Sclaverei und Freiheit (the German title of Douglass’s book) for sensuous physical descriptions of Douglass as well as a spectacular tribute to his skills as an orator. Employing the words “brilliant” or “brilliance” three times in two sentences, Assing’s Douglass possessed “perfect mastery of language,” and the most “mellifluous, sonorous, flexible . . . voice speaking to the heart as I have ever heard.” His very name filled American halls to overflowing, she maintained, “as if a new apostle had revealed to them for the first time a truth that had lain unspoken in everyone’s heart.”26

Assing identified Douglass as a “light mulatto of unusually tall, slender, and powerful stature.” “His features are striking,” she gushed: “the prominently domed forehead with a peculiarly deep cleft at the base of the nose, an aquiline nose, and the narrow, beautifully carved lips betray more of his white than his black origin. The thick hair, here and there with touches of gray, is frizzy and unruly but not wooly.” Having dispensed with these common nineteenth-century racialized depictions, Assing made it clear she had found a romantic hero for the age: Douglass’s “whole appearance, stamped by past storms and struggles, bespeaks great energy and will power that shuns no obstacle . . . in the face of all odds.” She observed briefly their wide-ranging conversation, then, in a telling non sequitur, acknowledged bluntly that she met the family: “Douglass’s wife is completely black, and his five children, therefore, have more of the traits of the Negro than he.” The family, especially the children, would get to know Assing as friend, intruder, and benefactor. The German journalist, with her powers of observation, had found her Siegfried ready to go slay the American dragons.27 Assing’s attraction to Douglass was permanent, and she would do her best as a propagandist, at least for German audiences, to shape the Rochester editor’s reputation in relation to John Brown.

• • •

The saga of how Douglass and Brown forged an important, if tragic, alliance publicly commenced at the inaugural convention of the Radical Abolition Party in Syracuse, New York, June 26–28, 1855. By then, five of Brown’s sons, led by John Jr., whose farm in Ohio was failing from drought and debt, had moved to Kansas. That territory had become the feverish test case of the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” laid out in the fateful Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Flocks of proslavery and Free Soil settlers were moving into the land west of Missouri, and the region teetered on the brink of guerrilla war. Brown praised his sons for their commitment to go to Kansas “with a view to help defeat SATAN and his legions.” The father was still committed to his work among blacks in North Elba, but by the spring of 1855, John Jr. wrote from his farm near Osawatomie that “every slaveholding state is furnishing men and money to fasten Slavery upon this glorious land, by means no matter how foul.” When his father trekked over hill and dale for 150 miles to get to Syracuse for the convention of the only political party Brown may have ever joined, Kansas not only fired his imagination, but that of the nearly three hundred delegates as well.28

The Radical Abolition Party lasted a mere five years. At the 1855 gathering, McCune Smith chaired the proceedings, which Douglass especially celebrated as something to which black people could “ever proudly refer.” Gerrit Smith was in his glory as the primary host and funder of the proceeding; and the convention spent a great deal of time debating and justifying what Douglass referred to as the “iron-linked logic” of the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution. Most important, the convention’s delegates from ten states and Canada passed a resolution affirming the use of violence to overthrow slavery. Brown was exhilarated by the convention. According to Douglass, Brown presented the case for his own decision and that of his sons to go to Kansas and fight for the free-state cause. Brown quoted from Hebrews as he also appealed for money: “Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin.” Gerrit Smith read two letters aloud to the assembled body from Brown’s sons to their father, which only the proud patriarch could have provided. In one letter they advised the abolitionists to “thoroughly arm and organize themselves” as they begged for revolvers, rifles, and bowie knives, which they needed “more than . . . bread.”29

This gathering exuded a radical, biblical militancy not yet seen in formal political abolitionism. McCune Smith used the term “Bible politics” to describe the party’s point of view and called its platform a “Jubilee doctrine . . . more important than the diffusion of the principle of science.” The biracial throng of abolitionists, the physician announced, would “go hence to proclaim the gospel of liberty—for it is the good news, glad tidings of great joy, that we have to tell.” Douglass seems to have left Syracuse inspired as well. In his paper he especially reported on the “sweet” abolition songs at the Radicals’ convention, as well as that one delegate had been a fugitive slave who had “been obliged to avail himself of the underground railroad” in order to participate and was now safely residing in Canada. But above all, Douglass said that he and his comrades at Syracuse were fed up with the idea of limiting slavery and hoping that it “may die out.” He said he now belonged to a party that would lay “the axe to the tree” with a single demand: that it was “THE RIGHT, THE POWER, AND THE DUTY OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT TO ABOLISH SLAVERY IN EVERY STATE IN THE AMERICAN UNION.”30 Behind the scenes in Syracuse he had conversations with Brown and helped raise money for his cause. The two would not meet again until late 1856, after the intriguing radical had carved out a bloody history in Kansas and launched a conspiracy to attack slavery in the South with which Douglass became deeply entwined.

No one who knew John Brown ever doubted his bravery, his passion, or that he believed he was living and dying as an agent in God’s plan. He went to Kansas in the fall of 1855 to make war on slavery. As Douglass published and promoted Bondage and Freedom that autumn, Brown, accompanied by his teenage son Oliver and a son-in-law, Henry Thompson, traveled west to eastern Kansas primarily by walking, but also with a horse and a wagon full of weapons. There, with parts of his extended family, including women and children, living in tents and shanties, the fifty-five-year-old, soon called Captain Brown, led a band of warriors among the free-state forces in what soon became “Bleeding Kansas.”31

Kansas was a brutal physical and political environment. Members of Brown’s clan suffered frostbite and near starvation during the winter of 1855–56, and by that spring, the numerous murders and depredations by proslavery “border ruffians” from Missouri signaled the wider bloodshed to follow. In May 1856, after proslavery bands attacked and burned Lawrence, Kansas, the Free Soil bastion of the territory, Brown snapped with rage. In retaliation, and against the wishes of some of his sons, Brown orchestrated a bloody middle-of-the-night raid on three proslavery dwellings along Pottawatomie Creek, resulting in the savage murder of five men. The victims, all non-slaveholders but supporters of the slave-state cause, were seized from the clutches of their families, taken a couple hundred yards from their cabins, and slashed to death and mutilated with broadswords. At least two were also shot in the face or chest, likely after they were already dead. The “Pottawatomie massacre” would forever be part of John Brown’s legacy, an uncomfortable challenge to his sympathetic biographers, but ample evidence to those who take a clear-eyed look at how Old Brown understood the uses and meaning of terror. Brown planned and ordered the murders, and though he may not have actually committed the slashings, he may have fired the gun. Back east, among his abolitionist supporters and funders, the facts about Pottawatomie remained for the ensuing three years a matter of willful mystery and avoidance, as well as part of a legend that the “Old warrior” now cultivated about himself in the service of broader schemes.32

In December 1856, as Brown was traveling eastward to raise money and men, he stopped in Rochester and took dinner at Douglass’s house. Little is known of what they discussed that evening, but in the next two years their collaboration deepened as Brown repeatedly tried to recruit Douglass to the cause of fomenting a slave uprising in Virginia. Possibly they discussed Brown’s long-standing interest in military history, slave revolts, and Maroon colonies, as well as some details of the Kansas bloodshed. Whether Brown divulged the reality of Pottawatomie is doubtful, although the idea of slaveholders’ blood on Brown’s coat, whether fresh from the Battle of Osawatomie or from a preemptive, primal killing in the dark of the night, would only have inspired Douglass. But by the time he wrote about Brown with long retrospect in 1881, Douglass knew and approved of what had happened in Kansas. By then Brown was the mythic hero whose “hour had come.” Old “Osawatomie Brown” had merely “met persecution with persecution, and house-burning with signal and terrible retaliation.” In Life and Times Douglass harbored no hesitation in defending Brown’s deeds and methods, and likewise, in 1857 it is not likely he did either. “The horrors wrought by his iron hand,” Douglass wrote, “cannot be contemplated without a shudder, but it is the shudder which one feels at the execution of a murderer . . . necessity is the full justification of it to reason.”33 His problem with the Old Man was strategic, not ethical, although Douglass continually struggled to square killing with reason.

Above all, Brown needed money. Throughout most of 1857, he traveled across the North, fashioning Kansas as a moral crusade and enlisting some of the most prominent abolitionists in his effort. In March in Worcester, Massachusetts, Brown was a platform guest as Douglass gave a speech. But Brown’s fund-raising efforts floundered as the economic panic of 1857 swept across the country. Staying with abolitionist allies, Brown wrote numerous letters in which he appealed to the New England antislavery conscience as well as for his destitute family and band of soldiers. He made many important connections with abolitionists who were convinced that the Kansas free-state cause demanded their moral and financial support. Gradually, Brown managed a tempestuous alliance with a “secret six” group of activists including Samuel Gridley Howe, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Franklin Sanborn, Theodore Parker, Gerrit Smith, and especially George Luther Stearns, a self-made magnate enriched by linseed oil and lead-pipe manufacturing, who, after his wife received Brown’s appeal, pledged thousands of dollars. All in their own ways were attracted to Brown as a romantic warrior-hero who would take the antislavery cause to the field of battle as none of them could.34

Like many of his fellow abolitionists, Douglass no longer had to imagine or invent a John Brown; he showed up at Douglass’s doorstep, hat in hand, but also again with maps, plans, and half-told tales. In the last week of January 1858, Brown arrived in Rochester and became a boarder with Douglass’s family at $3 per week for three weeks. From this and other encounters, Douglass became as well informed of Brown’s ultimate aims as any abolitionist or accomplice outside of his small personal band. From upstairs at Douglass’s house, and in secrecy using the alias N. (Nelson) Hawkins, Brown carried on a near-daily correspondence with his family and with potential supporters and donors. To Higginson, Gerrit Smith, Sanborn, and Stearns he wrote cryptically of his “Rail Road business of a somewhat extended scale” as he asked for money to accomplish his clandestine work. As the letters flowed in and out of the house, with thirteen-year-old Charles Douglass as the carrier to and from the post office, Douglass learned intimately of Brown’s “plan of running off slaves” by establishing safe locations in the mountains of Virginia. Such a scheme for “rendering slave property in Maryland and Virginia valueless [and] insecure” intrigued Douglass, who recalled his own desperation for “any new mode of attack” on slavery.35

Also while staying with the Douglasses, and eating at Anna’s table, Brown drafted his “Provisional Constitution,” which he intended to put in place as an interim government in Virginia if his invasion succeeded. Just how much Brown and Douglass debated political philosophy and constitutionalism is unknown, but Douglass kept a personal copy of the constitution with its forty-eight articles, which together provided a bold, if redundant, blueprint first for revolution and then for order to control anarchy and chaos in wartime. Above all, Douglass surely agreed wholeheartedly with Brown’s preamble, much of which could have been lifted from editorials and speeches written by the host. The provisional government would be established in the name of the “proscribed, oppressed, and enslaved citizens . . . of the United States.” Slavery, proclaimed the document’s first line, “is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion—the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude or absolute extermination.” Brown wrote the document to present to a convention in Chatham, Canada, that he would convene in May 1858 as a means of recruiting among the substantial free-black and fugitive community in that region of western Ontario. That convention did eventually attract thirty-four black and twelve white delegates, but the only noted black abolitionist was Martin Delany, then living in Canada; the whites were primarily members of Brown’s Kansas band of soldiers. Notably, neither Douglass nor any of the New England backers of Brown’s crusade attended.36

Philosophizing about the nature of slavery and how it poisoned American institutions was one thing; fomenting an abolitionist revolution and creating a government in the midst of a slave state were quite another. Douglass described Brown as obsessed with his constitution during the winter days in Rochester. “It was the first thing in the morning, and the last thing at night,” Douglass recalled, “till I confess it began to be something of a bore to me.” This remarkable comment reflected Douglass’s response to the bizarre character of the constitution, and an admission that Brown’s personality, as well as his combination of zeal and lack of clarity, could wear down a busy, discerning person such as Douglass. The autobiographer remembered the Old Man mentioning the possibility of attacking the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry to seize weapons. Douglass soon realized the gravity of such a turn in the warrior’s vision. Brown asked Douglass to put out two planed boards, on which Brown diagrammed “forts” and “secret passages” in the mountains where he would stage his revolution. Douglass began to listen with caution. He admitted that he was less interested in the drawings and board gaming than his children were. Brown even used a set of blocks to illustrate his plans to the assembled children, who surely never forgot those wintry evenings. What Anna Douglass thought of this austere man with the long white beard whom she was feeding each day is not known. On February 4 he wrote to his eldest son that Douglass had promised him $50, but “what I value vastly more he seems to appreciate my theories & my labors.”37

Perhaps, but Douglass’s wry remembrances of those “theories,” as well as his actions, remind us of the most basic fact in this union of awkward allies. As long as Brown bravely advanced the idea of funneling fugitive slaves out of the upper South and thereby politically threatened the slave system generally, Douglass was on board despite the risks. But when assaulting a large US arsenal emerged in the scheme, the writer parted ways with the warrior.

Douglass also performed as a conduit, even a kind of banker, for Brown with other black leaders; they sent modest drafts of money to Rochester for the editor to pass on to the revolutionary. In mid-March in Philadelphia, Brown and John Jr. met with Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, and the famed Underground Railroad activist William Still. They gathered at the home of Stephen Smith, a successful black lumber dealer and protector of runaway slaves in that city. What Brown or Douglass might have divulged about invasion or insurrectionary plans is not known; these and other meetings like them were essentially to prime the pump of a constant fund-raising campaign. But through most of 1857–58 Brown’s clandestine enterprise was broke. He established a training base in Tabor, Iowa, for his diminishing band of men. He then squandered an exorbitant amount of money hiring a soldier of fortune, Hugh Forbes, an English fencing teacher Brown had met in New York City who had fought in the Italian Revolution with Giuseppe Garibaldi and promised to write a training manual and serve as the drill instructor. Unfortunately, Forbes was a scoundrel who sought to enrich himself off New England humanitarians as he betrayed the invasion plan to high American officials when he did not receive his promised compensation.38

In late March 1858, Brown paid a ten-day visit to his home, his wife, Mary, and their small children in North Elba, New York. This may have been a kind of leave-taking since he planned to launch the Virginia adventure later that spring or early summer. Surely Brown sought emotional solace in what was left of his devastated family. Six of Brown’s sons and one son-in-law had fought in Kansas. By that spring, one was dead, two badly wounded, and two others had undergone imprisonment, torture, and severe mental breakdowns. In letters Brown wrote from his retreat at Douglass’s home in February, he had counseled Mary and the family, “Courage, courage, courage!—the great work of my life (the unseen Hand that ‘guided me, and who has indeed holden my right hand, may hold it still’) . . . I may yet see accomplished.”39 Kansas and ultimately Harpers Ferry were a gruesome disaster that Brown brought upon his own family; in the face of such poverty and loss, he, not to mention his wife and surviving children, needed a profound faith in that helping hand.

On April 4 Brown once again arrived in Rochester, where he spent a night with Douglass. Accompanied by the former fugitive slave Jermain Loguen, and still preparing and recruiting for his convention in Chatham the next month, he then traveled to St. Catherines, Canada, to visit and try to enlist Harriet Tubman in his cause. The legendary Tubman, with her years of experience rescuing slaves in Maryland, Virginia, and Delaware, now lived in St. Catherines. Although she encouraged and advised Brown and left the Old Man in awe, she never made any promises to join him. If he could muster enough men, money, and guns, Brown had planned to launch his raid in 1858 soon after the Chatham gathering. But the knave Hugh Forbes, claiming lack of payment, informed three US senators, as well as the editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, of the operation. The entire scheme was therefore postponed for at least a year. Although Douglass met with and paid the hotel bill for Forbes when he visited Rochester seeking personal funds in late 1857, the editor exaggerated his own role in exposing the Englishman’s betrayals to Brown (claiming to have first broken the news). Douglass had embarrassing tracks to cover on this count; through his friend Ottilie Assing he had introduced Forbes to a series of New York acquaintances as potential donors, all of which only added to the danger of blown secrecy.40

The “Forbes postponement,” as participants and scholars came to call it, forced Brown to return to Kansas and lie relatively low until 1859. The fifty-eight-year-old with the flowing white Moses-like beard fell ill for weeks with malarial fevers. He chose yet another new alias, Shubel Morgan, the first name meaning “captive of God.” Hatred and violence over the slavery question still roiled in Kansas. In December 1858, a slave named Jim Daniels crossed over from Missouri, found Brown, and summoned his assistance in protecting him and his young family from their owner, who intended to sell them away southward. Physically recovered, Brown strapped on his guns and led eighteen guerrillas into Missouri; they liberated Daniels’s family as well as one other group of slaves from two farms, resulting in the death of one slaveholder, and spirited the eleven rescued people back into Kansas. Here finally—Brown had liberated slaves from under the noses of their owners.41 Then what ensued was possibly the most heroic and admirable feat of Brown’s troubled career.

After hiding in makeshift quarters and among antislavery settlers in Kansas for a month, Brown led an epic eighty-two-day, thousand-mile midwinter trek, on foot and horseback, as well as with an oxen-driven wagon, across Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, and Michigan. With the aid especially of abolitionist activists in Grinnell, Iowa, Brown and his liberated entourage eventually rode in a special boxcar by train to Chicago and on to Detroit. On a blustery March 12, 1859, Brown bid a tearful farewell to the now twelve liberated blacks as they were spirited to freedom across the Detroit River at Windsor, Ontario. Back in Kansas, Jim Daniels’s wife had given birth to a baby boy christened John Brown Daniels. When Brown’s daughter Ruth asked him later about his feelings during that scene on the Detroit River, her father merely answered with Scripture: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: For mine eyes have seen thy salvation.”42

That night in Detroit, Brown returned to earthly matters as he met with Douglass, who was on an extended western speaking tour. Brown had written ahead when he heard of Douglass’s presence and urged him to wait for a rendezvous. Douglass heard Brown’s latest plans among a group of black Detroiters, led by George DeBaptiste, the militant leader of that city’s Colored Vigilance Committee, which worked to direct fugitive slaves into Canada. Despite the success of the Missouri rescue, Douglass had gone cold on Brown’s scheme, especially if it included Harpers Ferry. The Old Man’s heroic image was now thoroughly compelling; he was the revolutionary that abolitionists such as Douglass had yearned for. Or was he? That winter, during the rescue journey, Douglass’s daughter Rosetta wrote to her father demonstrating how the warrior had become an intimate part of their family lore: “Old Brown will have to keep out of sight for a while. The governor of Missouri has a reward of $3000 offered for his capture.” In Brown’s travels eastward in mid-April for more money raising, he stopped by Douglass’s printing office for an afternoon to make yet another appeal to the most famous black activist. Brown believed, dubiously, that Douglass’s presence would attract other courageous blacks to the cause of violent action. Douglass provided a serious conversation, but no promises. He reported in his paper, though, very publicly, that “a hero . . . ‘Old Brown’ of Kansas memory” had just visited Rochester and made an appearance to speak at City Hall. His host was angry at local Republicans for their disappointing or cowardly turnout.43

• • •

Later that summer Brown rented a farmhouse (the Kennedy farm) in western Maryland, a mere five miles north of Harpers Ferry, as his secret staging base for the attack on the federal arsenal across the Virginia border. Douglass was certainly informed of the location and now of its purpose. He and Brown kept up a correspondence through that fateful summer, and on August 10 Douglass met with John Brown Jr. in Rochester. Soon after that encounter, the editor answered the Old Man’s summons to come meet him in a stone quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, just across from the Maryland line.44 Douglass recorded a detailed recollection of this fateful final meeting between the two men. In autobiographical time Douglass could control the narrative; but in real time on August 19–20, when he met the revolutionary, who was disguised as a fisherman and camped among bleak large stones, an agonized emotional tension enveloped their friendship.

Douglass brought a $20 contribution given him on a stop in New York City by a black couple, the Reverend James Glocester and his wife, as well as one significant recruit, a fugitive slave named Shields Green, who had escaped from slavery in Charleston, South Carolina. Green was a man of few words but steel nerves and had met Brown on one of his visits to Douglass in Rochester. As Douglass arrived in Chambersburg, a town with a sizable free-black population, he was immediately recognized and asked to deliver a speech. Not wishing to blow his cover, he responded as asked in a local black church. Then for two days Brown and Douglass, along with John Kagi, one of Brown’s most trusted aides-de-camp (with Green present as well), debated the Harpers Ferry scheme. Douglass did not exaggerate when he remembered feeling that he “was on a dangerous mission.” Indeed, at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, and only sixty-five miles from Washington, DC, the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry housed the largest stash of munitions in the United States. Brown begged Douglass to join him for the raid, as Douglass listened but resisted and then vehemently strove to dissuade the Old Man from the attack. Brown looked bedraggled, “storm-beaten . . . his clothing . . . about the color of the stone quarry itself.” But the final realization of his imminent invasion of Virginia put fire in the Old Man’s eyes. Possibly Douglass still did not know fully of the intent to attack the arsenal until he arrived in Chambersburg, although he had heard it “hinted” at several times before.45

That Douglass made such an extremely risky trip to southern Pennsylvania at this late date may indicate that he knew a great deal, but perhaps not quite enough. It also reflected a kind of desperate loyalty he had always demonstrated toward Brown—showing up with money and a recruit, the two things the warrior had always sought. Still gravely in search of that logic of violence that he could embrace in the mind, not merely the heart, Douglass stepped away from Brown’s bleak, death-defying heroism. The writer-orator looked reality in the face and said a resounding no. At age forty-one, Douglass was not prepared to die in such futility.

Douglass told Brown that the raid would prove fatal to all earlier plans for running off slaves and the creation in the mountains of a militarized Underground Railroad, the one aspect of Brown’s schemes that attracted Douglass. Brown threw his arms around Douglass at their campfire and begged him to lend his life and reputation to the cause. “Come with me, Douglass,” Brown pled, “I will defend you with my life. I want you for a special purpose. When I strike the bees will begin to swarm, and I shall want you to help hive them.” But the former slave knew far too much about the instinctive suspicions of slaves toward their would-be liberators as well as about the bloodshed surely to follow any slave insurrection. Above all, Douglass looked Brown in the eye and told him that, despite his apparent aim of “rousing the nation,” he was attacking the federal government, which would marshal all its military might against him. He was “going into a perfect steel trap,” Douglass told Brown in no uncertain terms, and warned that “Virginia would blow him and his hostages sky-high, rather than that he should hold Harpers Ferry an hour.” The conversation deteriorated into a grim, if noble, despair. Douglass knew he had encountered a tragedy he could not stop. He let Shields Green make his own choice, and the young man’s response was simple: “I b’leve I’ll go wid de ole man.” Green would be captured at Harpers Ferry along with Brown and hanged on December 16, two weeks after the Old Man; his body was given for dissection to a Virginia medical school.46

Autobiography allows for an ordering of time and motives. In the clear-minded moment of August 20, 1859, Douglass made one of the great rational decisions of his life. Soon, though, the man who had expended so much rhetoric advocating violence in the 1850s would have to explain himself as an exile in a doubting world.

• • •

In the first nine months of 1859, before Harpers Ferry changed everything, Douglass had hardly sat on his hands waiting for Brown to strike his blows. From February 1 to March 12, Douglass launched one of his exhausting lecture tours across the Midwest in the states of Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. He delivered some fifty speeches in six weeks. Douglass encountered no mobs and only a little hostility (he was viciously Jim-Crowed in a hotel in Janesville, Wisconsin). He found the tour debilitating but “soul-cheering”; as a black voice he served as an “excellent thermometer” of the political climate. The slavery question seemed uppermost in everyone’s mind among his huge audiences that spring. In the heartland where the Republican Party found its deepest allegiances, Douglass kept up steady criticism of the party’s moderate policies, especially its tendency to support “exclusion” laws to deny settlement by blacks in western territories. He attacked Republicans’ Free-Soilism as never enough, calling it “an inconsistent, vacillating, crooked and compromising advocacy of a good cause.” During his absence from the Douglass’ Monthly (the name was newly changed), he gave over the editor’s chair to McCune Smith, who dazzled the paper’s readers with essays on black education, self-reliance, suffrage, and politics. The orator might have also given himself over to full-time lecturing for a while as a fund-raiser; he repeatedly appealed to his subscribers to pay up and keep his paper afloat.47

While John Brown plotted, Douglass kept up a steady and fierce debate with fellow black leaders such as Henry Highland Garnet over emigration schemes. Douglass respected Garnet and the right to emigrate, but attacked the idea of willful African American removal from the United States. Douglass loathed the notion that some of the best black leaders would abandon the American ship at this pivotal hour in history. Garnet’s mission was to extend “civilization and Christianity” to the heathen of Africa, and to end slave trading, but Douglass, who referred to West African rulers who sold slaves as “savage,” angrily insisted that American slaves must be freed first.48

In January 1859 Garnet and Douglass exchanged honest missives, disagreeing vehemently. Garnet accused his “dear brother” of enjoying the “comforts of the editorial chair” rather than venturing to Africa to make a new civilization for their people. Garnet even accused the editor of a “toil-fearing spirit.” Douglass reacted with grace but firmly condemned once again all forms of colonization as false prophecy and a historical dead end. Although he sometimes expressed modest interest in possible migrations to Haiti, to Douglass, removal, even in the wake of Dred Scott, only fueled the idea that black people could never be equal in America. The best way to defeat racism, said the editor, was to stop “with wandering eyes and open mouths, looking out for some mighty revolution in our affairs here, which is to remove us from this country.” Douglass and Garnet wanted different revolutions. “You go there, we stay here, is just the difference between us,” Douglass told the minister.49

Douglass sustained as well his radical critique of Republicans, demanding that abolitionists “return to your principles” and reject appeals on “behalf of free white labor.” Energized by the public lectern, throughout 1859 Douglass kept up his drumbeat against racial segregation and about uses of force. With special urgency, by summer he blasted the limits of Republican “non-extension,” calling the slave system “a fiery dragon” sweeping across the South. “While the monster lives,” Douglass characteristically declared, “he will hunger and thirst, breathe and expand. The true way is to put the knife into its quivering heart.”50 Rhetorically, Douglass had long been ready for violence.

Among the final editorials Douglass wrote before Harpers Ferry was one entitled “The Ballot and the Bullet.” The piece is a measure of Douglass’s frustrations as well as his passions. Reacting ostensibly to a Garrisonian challenge that abolitionists should employ only the “sword of the spirit” and abandon all appeals to the ballot or the bullet, Douglass reflexively declared such a debate “nonsense.” “Hearts and consciences” were crucial, he admitted, but “truth to be efficient must be uttered in action as well as in speech.” If speech could end slavery, Douglass said, it “would have been done long ago.” He demanded an “anti-slavery Government,” but the political system seemed to offer only “can’t,” and he was “sick of it.” Hence, the “ballot is needed, and if this will not be heard and heeded, then the bullet.” “Law” was necessary, but so was “physical force.”51 As an exclamation point on the bankruptcy of moral suasion, Douglass also unwittingly exhibited that an expectation, even a justification, for violence could leave a gaping, unbearable chasm between words and actions.

• • •

When news broke about the raid on Harpers Ferry on October 17–18, Douglass was in Philadelphia, where he gave a speech at National Hall. Late on the night of October 16, Brown and his eighteen men had seized the arsenal. Within thirty-six hours the raid was over; ten of Brown’s men were killed in the raid, some captured, including the badly wounded Brown himself. While five escaped, three of whom would die fighting in the Civil War, the captives were hanged in the coming months by the state of Virginia. Three slaves temporarily liberated by Brown’s band died in the raid or its aftermath. Five town residents or workers, including the Harpers Ferry mayor, were killed, and nine militiamen or US marines were wounded in the day of street battles. The raid was a strategic disaster, yet with time emerged as the most catalytic and successful symbolic event in the history of the antislavery cause. Newspapers screamed with shocking and confused headlines such as the litany on the cover of the New York Herald for October 18: “Fearful and Exciting Intelligence”; “Extensive Negro Conspiracy”; “Seizure of United States Arsenal by the Insurrectionists.” Within a day of Brown’s capture and arrest Douglass’s name appeared in newspapers across the country as one of the conspirators identified in a large collection of papers confiscated from a trunk left at the Kennedy farm in Maryland. Wild rumors mixed with some facts as many newspapers gave over their entire sheets for days to telegraphic reports about Harpers Ferry. By October 29 Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper began its extraordinary pictorial coverage of Brown, the raid, the trials, and the executions, giving the country a feast of images well into 1860. There had never been an event like this in American history; Douglass recalled it as news with “the startling effect of an earthquake . . . something to make the boldest hold his breath.”52

Douglass quickly realized he was in dire trouble. He delivered his Philadelphia lecture in which he openly referred to Brown’s raid approvingly. But soon afterward he was informed by friends that John Hurn, the city’s sympathetic antislavery telegraph operator, had received a dispatch from government authorities to the local sheriff ordering that Douglass be arrested and detained as a conspirator. Hurn delayed its delivery for three hours as long as friends “agreed to get Mr. Douglass out of the state.” (Hurn became a prominent photographer, and Douglass sat no fewer than eight times for him in the 1860s and 1870s, a measure of the bond the two men developed.53)

Douglass swiftly departed from the Walnut Street wharf over to Camden, New Jersey, a route he remembered well from his escape to freedom in 1838. Now he was a fugitive again of another kind. Hurrying northward, he took the train to New York, and late on the night of October 19 he caught the ferry to Hoboken, to the home of Mrs. Marks, where Ottilie Assing lived as a boarder. There Douglass spent the night as he made a risky decision to use the railroads to continue his flight home to Rochester. Worried about “sundry letters and a constitution written by John Brown” locked in his desk in Rochester, he dictated a telegram to Assing to be sent the next morning to Douglass’s eldest son, Lewis. Addressed to the telegraph operator in Rochester, whom the editor knew well, it read, “B. F. Blackall, Esq: Tell Lewis (my oldest son) to secure all the important papers in my high desk.” To keep secrecy, he did not sign his name. In the Life and Times reminiscence, Douglass observed that in the 1880s the “mark of the chisel” still remained on the old desk, where Lewis had pried it open, one of the family “traces of the John Brown raid.” Both John Hurn and Assing eventually staked claims to having saved Douglass’s life.54

On October 20, Assing and another neighbor took Douglass in the dark of night in a private carriage to Paterson, New Jersey, so that he could take the Erie Railroad to Rochester, not the train he might normally be expected to occupy. He arrived safely, but immediately was informed by his neighbor Samuel Porter that the New York lieutenant governor was prepared to arrest Douglass if Governor Henry Wise of Virginia, now in charge of the investigation, issued such an order. Indeed, Wise was especially determined to capture Douglass, who eventually reprinted the Virginia governor’s remarkable letter to President James Buchanan, requesting his assistance in finding and apprehending “the person of Frederick Douglass, a negro man . . . charged with murder, robbery, and inciting servile insurrection.” In emotional desperation, with hardly time for a serious reckoning with Anna and his children, Douglass packed a bag, and by what was likely October 22, Amy and Isaac Post drove him to the docks and a ferry across Lake Ontario into Canada. It was widely reported that Douglass escaped from Rochester a mere six hours before federal marshals arrived at his home seeking his arrest.55

Anna’s despair and his children’s fears can only be imagined. They had by then lost count of the times when they felt abandoned by their beloved husband and father; but this time it may have felt as if their world had ended. The countless earlier appeals for the blood of slaveholders had found an astounding result fraught with horrible uncertainty.

In Canada, Douglass first stayed in a tavern in Clifton, which is today Niagara Falls. He was due west of Rochester, although soon it became clear that he could not go home anytime soon. Not only was Henry Wise searching for him, but he soon learned of severe criticism from one of Brown’s captured men, John Cook, as well as from some black leaders claiming that the abolitionist had promised to join the raid and betrayed the cause. Douglass may have let the sound and awe of the falls soothe his psyche; he certainly did not fall on his sword with guilt and affliction, although the accusations put him painfully on the defensive. On October 27 he wrote to Amy Post in Rochester implying that he would return to the New York side of the border soon, admitting however that it “will take many months to blow this heavy cloud from my sky.” He hated his current exile and worried about the possible confiscation of his property if his indictment held. But he whistled with false confidence: “It cannot be lost unless I am convicted. I cannot be convicted if I am not tried. . . . I cannot be arrested unless caught; I cannot be caught if I keep out of the way—and just this thing it is my purpose to do.”56

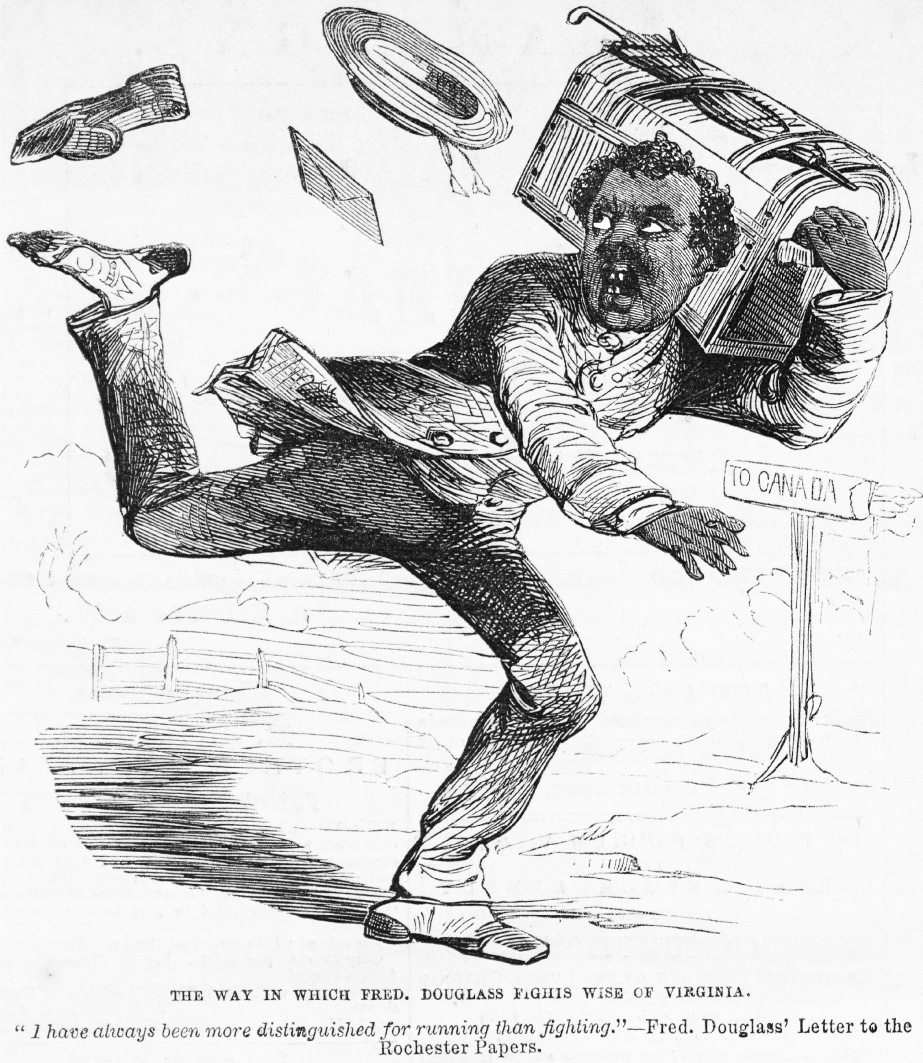

On October 31 Douglass responded the only way he could—with his pen in a public letter to a Rochester newspaper that was in turn reprinted all over the country. To Cook’s jailhouse accusation of “cowardice” against him, Douglass first blamed the hothouse of “terror-stricken slaveholders” surrounding the sensational situation in Virginia. Then, with a degree of comic irony he may have regretted, he answered the personal charge: “I have not one word to say in defense or vindication of my character for courage. I have always been more distinguished for running than fighting—and tried by the Harpers Ferry insurrection test, I am most miserably deficient in courage.” Soon he would have to endure an extraordinary cartoon that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, depicting Douglass leaping through the air in sheer fright with a trunk on his shoulder, his shoes and hat flying off. To his side is the small signpost TO CANADA; the title reads, “The Way in Which Fred. Douglass Fights Wise of Virginia,” and the caption below, “I have always been more distinguished for running than fighting.”57

“The Way in Which Frederick Douglass Fights Wise of Virginia,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 12, 1859.

Douglass unequivocally denied ever promising to join Brown’s band at Harpers Ferry. Whether from wisdom or cowardice, Douglass said, his “field of labor for the abolition of slavery has not extended to an attack upon the United States arsenal.” He did not fear being “made an accomplice in the general conspiracy against slavery.” Then he succinctly stated his long-term dilemma with violence: “I am ever ready to write, speak, publish, organize, combine, and even to conspire against slavery, when there is a reasonable hope for success.” Such had been the gaping hole in his quest for the logic of violence, as in the earlier Chambersburg moment of truth. As to why he had not joined Brown in Virginia, Douglass gave an honest answer: “The tools to those that can use them.”58 There was a time for every purpose—for the war makers, and for the war propagandists. Douglass knew his tools.

Also while sitting in Clifton, Canada, and reading wire dispatches and newspapers, Douglass followed Brown’s celebrated trial in Charles Town, Virginia, which began on October 25. He penned an extraordinary column for his paper, “Capt. John Brown Not Insane,” which was not only a vintage, sharp-edged piece of abolitionism, but also Douglass’s earliest effort to help build the majestic cross of John Brown’s martyrdom. To allow a charge of insanity for Brown soiled “this glorious martyr of liberty.” Had Americans “forgotten their own heroic age?” Douglass wondered, as he quickly marched Brown into line next to the “heroes of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill.” Brown was already “Gideon” of “self-forgetful heroism.” All the bad strategy and exasperatingly mysterious plans evaporated in the preparation for the gallows. John Brown had never made it easy to love him, until he found what one scholar has called his “creative vocation” of seeking martyrdom.59

Within two weeks of his capture, the bearded prophetlike hero had suddenly offered the nation a new history. Douglass was already writing a first chapter, almost a prose equivalent of the song “John Brown’s Body.” “This age is too gross and sensual to appreciate his deeds, and so calls him mad,” Douglass wrote, “but the future will write his epitaph upon the hearts of a people freed from slavery, because he struck the first effectual blow.” Douglass realized in mythic terms his logic of violence; Brown had used the “weapons precisely adapted” to destroy slavery. As poems, songs, and editorials flowed forth in American and European journals, Douglass made his own mark. “Like Samson,” said a lonely Douglass in Canada, Brown “has laid his hands upon the pillars of this great national temple of cruelty and blood, and when he falls, the temple will speedily crumble to its final doom.” Brown would have loved the metaphor since Samson was one of his own oft-repeated self-comparisons. “I expect to effect a mighty conquest,” Brown had written with customary grandiosity in 1858, “even though it will be like the last victory of Samson.”60 Douglass and Brown could both claim old biblical stories that each man had expected their America to reenact.

In the second week of November, Douglass passed through Toronto, took a steamer across Lake Ontario and down the Saint Lawrence River to Quebec, where on the twelfth he departed on the ship Nova Scotia for Liverpool. He feared, as he remembered many years later, that he “was going into exile, perhaps for life.” On the bitterly cold decks of a ship in the North Atlantic, Douglass felt deeply troubled. In two sittings aboard the ship on its ten-day voyage to Liverpool, the lonely exile crafted a long letter. He amused himself and settled his nerves with comments on the Frenchness of Montreal, the majesties of the ocean, and the sturdiness of the steamer. “My head is hardly less confused than the waves,” he admitted, “and my hand not more steady than the ship.”61 As John Brown eagerly charted his plan to die from his jail cell in Virginia, Douglass now had to plot a plan to live.