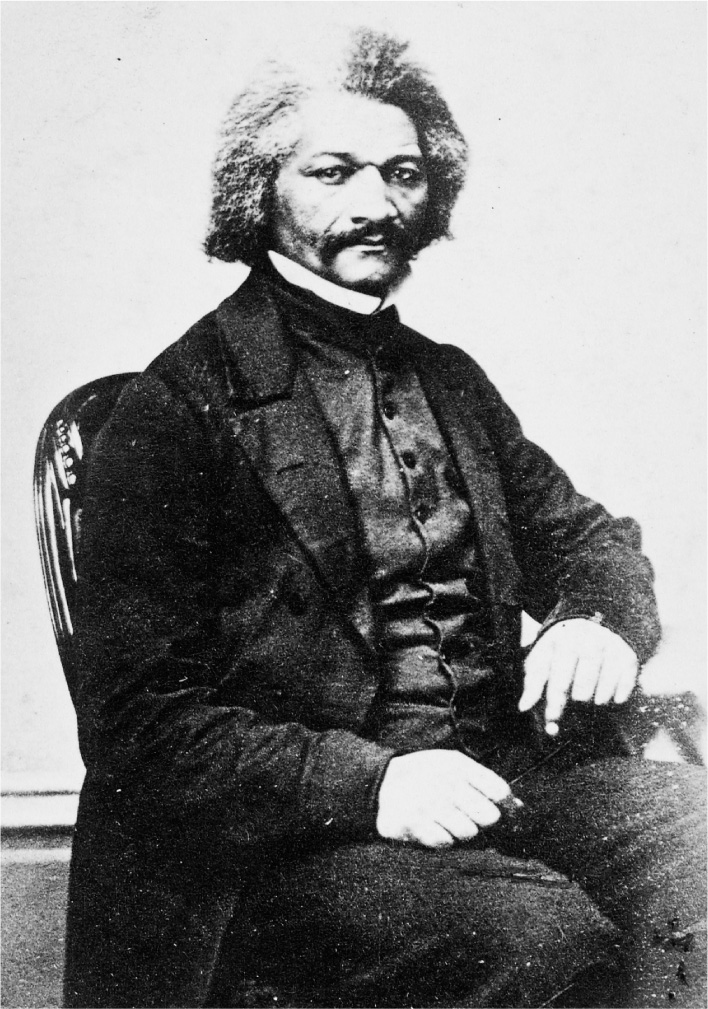

Frederick Douglass, Chicago, February 1864. Samuel Montegue Fassett photographer.

The most hopeful fact of the hour is that we are now in a salutary school—the school of affliction. If sharp and signal retribution, long protracted . . . and overwhelming, can teach a great nation . . . respect for justice, surely we will be taught now and for all time to come.

—FREDERICK DOUGLASS, FEBRUARY 1864

In Frederick Douglass’s view, during the final year and a half of the Civil War one America died a violent, necessary death; out of its ashes a second, redefined America came into being amid destruction and explosions of hope. At war’s end, Douglass could almost fashion himself as one of the unusual founders of this emerging second American republic, born in a revolution even bigger than the first. As 1864 dragged on, Douglass contemplated the war’s revolutionary and prophetic meaning for himself, his family, his people, and his nation. The issues of Reconstruction also captured his attention. Douglass sought to convince everyone of what he believed: the American nation, and history itself, had taken a rare, fundamentally moral turn.

Douglass took to the lecture circuit with “The Mission of the War,” his fullest expression of the war’s meaning. In Philadelphia on December 4, 1863, at the thirtieth-anniversary meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass offered a refutation (in the presence of his old mentor) of William Lloyd Garrison’s declaration that this might be the final meeting of the organization, now that emancipation had dawned. Announcing that “our work is not done,” Douglass warned of the deep racism within Northern society and in the Democratic Party. He especially called for black male suffrage. Casting the argument in humor, Douglass reminded his auditors that the American “body politic” had never been healthy. He had many times seen “Ignorance” trying to vote alongside a swerving man from the street with a “black eye.” And as he was long fond of saying, he had seen drunken “Pat, fresh from the Emerald Isle,” stepping up to the poll, “leaning upon the arms of two of his friends, unable to stand.” The franchise would protect blacks in the South, Douglass argued to rousing laughter and applause, from “the jaws of the wolf.” His people ought to be “members of Congress,” he asserted. “You may as well make up your minds that you have got to see something dark down that way. There is no way to get rid of it. I am a candidate already!” His Irish jokes notwithstanding, he left the abolitionists cheering as he demanded that they join his plea for an “Abolition war” and an “Abolition peace.”1

Douglass’s new speaking tour, like so many before, took on the character of a traveling crusade. Within two days he was in Washington, DC, where over consecutive nights, December 7–8, he delivered the “Mission” speech to overflow crowds at the African American Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church. More than a thousand people, according to a journalist, thronged the church, “jumping over the fence, some crawling over someone’s back,” jamming the sanctuary, filling the aisles, and sitting on the floor. With hats and bonnets falling off all around, the “glorious conglomeration” anticipated the arrival of the “African lion of the antislavery platform,” said the Christian Recorder. Amid shouting and applause Douglass slowly made his way down the crammed central aisle as the organ played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” He took the pulpit, told tales of his emotions while passing through Baltimore on his journey, and made his appeal for “Abolition war” to the finish, a struggle of conquest between “slavery and Liberty.”2

No one went home disappointed, since the following evening an equally packed and raucous crowd gathered to hear Douglass make his appeal for access to political rights, to the ballot box alongside the “drunken Irishman” and the “ignorant Dutchman.” Douglass soared rhetorically, calling on the nation to allow black men to “swell the body politic” as they helped win the war. The racially mixed audience all seemed pleased, said the correspondent: “They had seen the great Douglass.” As the celebrity orator held forth at Fifteenth Street Presbyterian with his vision of the apocalyptic revolution under way, some dozen blocks directly south, President Lincoln, on that same day of December 8, issued his annual message to Congress, in which he reflected on how the policy of emancipation had given “to the future a new aspect” and launched “a total revolution of labor” throughout the South. Within the same hours, both men, Lincoln with his pen, Douglass with his voice, imagined a nation “regenerated” through bloodshed on battlefields and the social misery in the streets surrounding them.3

In the crowd that swarmed around the church where Douglass appeared were many former slaves from the surrounding Virginia and Maryland countryside. Washington had become a massive military base, a series of hospitals functioning in churches, schools, and government buildings, and a massive street-based refugee camp. In 1862–63, a freedmen’s exodus had rolled into the capital, with thousands of refugees taking up residence in tar-paper shanties, and former soldiers’ barracks, such as Camp Barker, an old military residence and sometime prison converted into a tent city at Q and Twelfth Streets, near the current-day Logan Circle. By war’s end the black population of the District swelled to forty thousand.4 Douglass saw and likely visited Camp Barker since it was only four blocks east of the Fifteenth Street Church. Indeed, he made his “Mission” speaking tour, in part, a fund-raising campaign for contraband relief organizations.

During his stay in Washington, Douglass visited the burgeoning Freedmen’s Village contraband camp on Arlington Heights across the Potomac River, on the former estate of Robert E. Lee. His fellow slave-narrative author and former Rochester neighbor Harriet Jacobs worked in that camp and in others around the city. The “misery” she witnessed there had to “be seen to be believed,” she wrote. Refugees arrived daily from the war fronts of Virginia, and despite their destitution as well as the mistreatment many experienced from Union troops, she found these people “quick, intelligent, and full of the spirit of freedom.” “What but the love of freedom could bring these old people thither?” Jacobs unforgettably asked. During Douglass’s brief visit among the freedpeople in Arlington, as he strode for the first time on Virginia’s soil, a small ceremony was arranged at which a group of children sang for him. Only three days later, his close Rochester friend Amy Post visited the freedmen’s camps in Washington. Post left a detailed description of the Arlington site, met numerous former slaves of the Lee family, and observed “at the school room . . . Frederick Douglass’s autograph, which was the first intimation that he had visited any of the camps.”5

We do not have Douglass’s account of his own emotions, but he did write to friends describing the episode. In January 1864 he wrote to Julia Crofts in England; she felt thrilled to know that Douglass felt so moved by his “visit to Washington and Arlington Heights—how I should liked to have been an eyewitness of your visiting those dear . . . little children! & to have heard the singing!” “My eyes would not have been dry!” she continued, marveling at Douglass’s news of the “slaveholder’s smokehouse being converted into a school house for his freed slave children!” So eager were some of Douglass’s British friends for news of the war and his activities that Julia took his letters out on the circuit to local antislavery societies and tried to bolster support and raise money by reading “extracts of your letters relative to the contrabands.” Moreover, Douglass’s voice, in a manner, migrated into Germany in 1864 through the columns of Ottilie Assing in Morgenblatt. Partly by projecting Douglass’s ideas about the war, as well as with her own keen, radical observations, Assing told her readers in January that American abolitionists, despite their divisions, represented the “spirit of the nineteenth century” and of “civilized progress.” They represented the “vanguard of the present revolution, as Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau were the vanguard of the French Revolution.” By March, she considered black regiments marching south the best representation of “a great revolution.”6 In her passionate essays, Assing echoed her hero’s mission and emancipation as a world-historical event.

Close friends wrote to Douglass wondering when “your mission” would bring the orator to their town. From England, by April, the intrepid Julia Crofts sent £33 in contributions to contraband aid, as well as for “F. D.’s Mission,” from antislavery societies in Edinburgh, Liverpool, Coventry, and Aberdeen. Another old British friend, Mary Carpenter, joined Crofts in scolding Douglass for ceasing the publication of his paper, upon which British abolitionists depended so much for news of the cause. She wondered about the fate of the mission and where their hero traveled. “We know you live,” she said, “to promote that cause, but others ask what is F. D. doing now that his paper is given up.” Carpenter sent a check for £5 and felt resigned to “sympathize affectionately with you . . . in the painfully exciting life you must now be living.”7

Painful and exciting indeed. Sponsored by the Women’s Loyal League, an organization advocating a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, Douglass delivered the “Mission” speech to a packed house at the Cooper Institute in New York on January 13. He led with his millennial vision of the war, filling the hall with a tone of high moral certainty and with arguments both shuddering and hopeful. To Douglass the war in all its destruction was like a terrible, necessary gift from history and from Providence. The South’s rebellion was the “rapid educator” by which the Union leadership moved from “slave-hunting” on behalf of their enemies to now equipping the Negro with a Springfield rifle. Ever the earnest war propagandist, now in need more than ever, he believed, Douglass minced no words in describing the Confederacy as “a solitary and ghastly horror, without a parallel in the history of any nation,” a political crusade of “naked barbarism” in its attempt to give slavery an eternal foundation. He drew on Psalm 91 to make clear the character of the enemy: the Confederates and their cause “rivaled the earthquake, the whirlwind and the pestilence that walketh in darkness, and wasteth at noonday.” Confederates had to be met and slaughtered, no matter how “long and sanguinary” the struggle. The ferocity of Douglass’s language knew no limit; acknowledging that he had been accused of prolonging the war, his angry answer was “the longer the better if it must be so.” An audience that may have been a majority of women stood on their feet, waved their hats, and shouted approval.8

In thus sacralizing the killing of Southern soldiers and of the Confederacy itself, Douglass found the war’s meaning. The orator believed he described only stark facts: time and events, and fierce Southern resistance, had made the contest an “Abolition war.” Northern Democrats and white Southerners denounced “abolition war” as the inhumane path to sanguinary race war. Both sides felt something deeply sacred at stake, and no one more than Douglass. Yes, he acknowledged, the war was for Union and for the Constitution, but it must be a wholly new Union, and a new Constitution to replace the old one now torn and tattered. The country must not “put old wine in new bottles,” he argued, nor make “new cloth into old garments.” Douglass warned that liberal and open-minded people such as abolitionists themselves were rarely as unified as the forces of reaction and darkness. But in this historic moment, they had to be. “That old union,” he shouted, “whose canonized bones we saw hearsed in death and inurned under the frowning battlements of Sumter, we shall never see again while the world standeth.” Stop fighting for a “dead past,” Douglass urged his auditors, and instead fight “for the living present.”9 Here flowed a set of rebirth metaphors flaming, bloody, and much bolder than the succinct, if beautiful, suggestion in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. “Mission of the War” stood as Douglass’s radical abolitionist Gettysburg Address, a rhetorical sword into the Confederacy’s heart, and a statement of the war’s meaning as ancient as the Old Testament. Above all it was Douglass’s vision of the new founding of an American republic.

Douglass ultimately appropriated a common American language to capture the meaning of the war: “We have heard much in other days of manifest destiny. I don’t go all the lengths to which such theories are pressed, but I do believe that it is the manifest destiny of this war to unify and reorganize the institutions of this country—and that herein is the secret of the strength, the fortitude, the persistent energy, in a word the sacred significance of this war.” In a line that challenges us still in our moral imagination, Douglass said that without the destruction of slavery, the world might view the Civil War as only “little better than a gigantic enterprise for shedding human blood.”10

Not only had the war delivered the nation a “broken Constitution,” requiring a legal refounding, but history itself had been broken and had to be made anew. Douglass volunteered to lead a generation of new founders. “Events are mightier than our rulers,” Douglass asserted, and “Divine forces” had decided the mission of the war. The people had to line up, sacrifice, send forth their sons, and perform the sacred duty of holy war. Douglass left his rapt audiences that winter of 1864 with a clear, if harsh, message: “I end where I began—no war but an Abolition war; no peace but an Abolition peace; liberty for all, chains for none; the black man a soldier in war, a laborer in peace; a voter at the South as well as at the North; America his permanent home, and all Americans his fellow-countrymen.” In a finale that anticipates Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech a century later, Douglass invoked Isaiah once again: “Such, fellow-citizens, is my idea of the mission of the war. If accomplished, our glory as a nation will be complete, our peace will flow like a river, and our foundations will be the everlasting rocks.”11 Thousands heard Douglass deliver this speech; those drawn into his voice and his story were present at the new creation.

• • •

Dreams by definition, though, are always unfinished; this was certainly the case for Douglass’s blood-soaked vision of 1864. Imagining a new, reinvented country brought one challenge; but the war remained a very personal affair for Douglass and his family. In the fall of 1863 Rosetta Douglass gave up on her faltering teaching career and her formal education and took a husband. On Christmas Eve in Rochester, she married Nathan Sprague, a handsome former fugitive slave from Maryland who had been working as a gardener at the Douglass home. Rosetta very much resembled her mother, including her darker skin. Although unlike her mother, and very much modeling her father, she seemed to embrace having her photograph taken, especially in elegant earrings. Sprague was lighter and, in family lore, may have been descended from a Maryland governor, Samuel Sprigg. Over the next eleven years Rosetta and Nathan would have five daughters and one son. In this tempestuous marriage, Sprague never developed a gainful career and eventually caused financial and legal troubles for his father-in-law. Steadiness and talent were not his forte. Like her mother, though, Rosetta seems to have almost always stood by her husband. Douglass recruited Sprague into the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts before the wedding, and after living with Rosetta in the Douglass house on the hill on South Street in the winter months, he joined the regiment in the spring of 1864.12

After recovery from his wounds, Lewis Douglass tried to rejoin his regiment but was discharged formally on February 29, 1864. By that summer, Lewis traveled on army transports back to South Carolina, though not as an active-duty soldier. He witnessed the continual bombardment of Fort Sumter from Morris Island and, in August, wrote to his father, wishing the “state of New York would give me an appointment to recruit for them I could get a great many men.” In the sea islands Lewis saw the rich harvest of possible black soldiers for the Union army. His brother Frederick Jr. was at that very time in Vicksburg, Mississippi, recruiting among former slaves, witnessing the human and natural ravages of war as he tried to enlist men from cotton plantations. For the twenty-two-year-old namesake of his famous father, the world of the cotton kingdom under siege and devastation represented the revolution the elder Douglass had imagined. Nothing was more revolutionary than ushering former Cotton Belt slaves into Union blue. Details are elusive about just how Frederick Jr. functioned as a recruiter. Lewis, on the other hand, always had an eye out for how to make money from any circumstance, telling his father of “offers of partnership in business as a sutler” for the army.13

Charles Douglass, despite his recurring sickness, stayed in the army as long as he could, still trying to prove his courage and worthiness as a warrior. He was discharged from the Fifty-Fourth and transferred to the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry, where he served as a noncommissioned first sergeant. Through the awful summer of 1864, the delicate Charles served in Virginia during the early siege of Petersburg and at Point Lookout in Maryland, located at the southernmost tip of the peninsula on the Western Shore, where it meets the mouth of the Potomac River. Charles was now a soldier in the ranks of his dismounted unit, and he found his own real war. Black units of the United States Colored Troops were some of the first to occupy the City Point position where the James and Appomattox Rivers meet.14 City Point soon grew into the biggest military depot and headquarters of the war. His regiment had mercifully missed the horrific battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House in May, and they remained at City Point during the disastrous slaughter at Cold Harbor, fought just east of Richmond, June 1–3.

On May 31, in a letter to his father, Charles expected “to be called into line of battle every moment,” as he anticipated what became the beginnings of the siege of the city of Petersburg. With a soldier’s trembling bravado, he told his father that “our boys” are “anxious for a fight. . . . As for myself, I am not over anxious, but willing to meet the devils at any moment and take no prisoners.” Luck was Charles’s companion; his unit was kept largely in reserve on guard, picket, and logistical duties. Charles felt especially proud to report capturing a rebel prisoner while on picket duty. He also joyfully announced that they had brought in a large group of contrabands. He further reported an ugly tragedy—their commanding officer “had to shoot one of the men for being drunk and misbehaving, but the bullet hit the wrong man.” Charles dropped this pitiful irony almost as fast as he told it.15 All the Douglasses learned that this great revolution had an underside of horror, terror, and futility.

Later in the summer Charles’s health failed yet again, and he was transferred to the huge prison and hospital complex at Point Lookout. While stationed along the Chesapeake, Charles apparently took a brief leave, crossed the Bay, and went to St. Michaels, where he became the first member of the Douglass family to connect with some Bailey cousins. The war crushed one world and reconnected another. What Charles may or may not have known is that his father, who had now developed a relationship with Abraham Lincoln, had written to the president in late August asking him to intercede and formally discharge his son from the army. “I hope I shall not presume too much upon your kindness,” wrote the abolitionist to the commander in chief, “but I have a very great favor to ask. It is . . . that you will cause my son Charles R. Douglass . . . to be discharged.” On September 1, the president sent the letter to the War Department with the endorsement “Let this boy be discharged, A Lincoln.” On September 15 Charles wrote to both of his parents informing them that he was “honorably discharged [from] the service of the United States” and would be home within two weeks.16 Douglass had asked his sons to hear and follow his trumpet, to risk all for the cause of black freedom; now, he also reversed course, and with emotions he never fully described, did whatever he could to save one of them.

The summer and fall of 1864 were thus harrowing as well as hopeful months for the Douglass household in Rochester. They found great cause for personal relief, as both Lewis and Charles were out of the army, at least for the time being, and not in danger. Nathan Sprague still served with the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts, but Rosetta, pregnant with her first child, resided at home under her mother’s watch and care. Rosetta’s daughter, named Anna Rosine Sprague (called Annie for Rosetta’s deceased sister as well as her own mother) was born on November 27, giving the Douglasses their first of what would be twenty-one grandchildren.17 Although she probably retreated more and more now to her kitchen and garden, Anna Douglass happily had a new baby Annie in her house, as her husband, with no editor’s desk to retreat to, pondered and wandered the new political landscapes of a nation at war.

At the beginning of that bloody year, all three Douglass sons and one son-in-law had served at the war front in some capacity, while the patriarch himself rode the rails across the North on his mission to convince multitudes to fight the cruel war to its bitter end. All of Douglass’s children had to imagine their own new homes in this time of all-out war and revolutionary change as their father tried with the words and deeds of a self-styled prophet to influence history and power in the highest places.

• • •

In practical terms, what Douglass meant in his “Mission” speech by “abolition war” was a military conquest of the South, complete emancipation, continued enlistment of black soldiers without discrimination, and legal guarantees of black freedom and equal rights. An “abolition peace” would mean the subjugation of the Confederacy’s slaveholding and treasonous leadership, full black citizenship and enfranchisement, and a strong role for the federal government in protecting the freedpeople and in reconstructing Southern society. The war, this divine “school of affliction,” in Douglass’s words, provided the “signal and the necessity for a new order of social and political relations among the whole people.” Preserving the old Union was but a “miserable dream”; what Douglass the visionary wanted was a fundamentally new republic.18 Hence, as early as any Northern politician, he pondered the nature of the potential postwar Reconstruction.

As early as 1862 Douglass counseled his readers to hold no illusions about the difficulties blacks would face when emancipated. Indeed, the problems of peace suddenly seemed much greater than the problems of war. If emancipation was accomplished, Douglass surmised, it would happen in great violence, and its aftermath might prompt even greater backlashes of violence. “The sea of thought and feeling lashed into rage and fury by the war” might foment a frenzied wrath among the defeated. After the fighting, Douglass suggested, “will come the time for the exercise of the highest of all human faculties. A profounder wisdom, a holier zeal, than belongs to the prosecution of war will be required.” He wondered about uncharted constitutional terrain, about the use of federal authority in reconstructing state governments. Although he was no more prescient than the next person, Douglass envisioned Reconstruction as a long ideological struggle. “The work before us is nothing but a radical revolution,” he declared in an editorial, “in all the modes of thought which have flourished under the . . . slave system.” A new order could not happen overnight. “There is no such thing as immediate Emancipation either for the master or for the slave,” he asserted. The “invisible chains of slavery” might take generations to break, Douglass predicted with an uncanny, tragic foresight.19

Naturally, Douglass’s wartime concern with Reconstruction centered upon the welfare of the freedmen, and he laid out a paradoxical prescription combining classic self-help with outside philanthropy and activist government intervention. His early answer to the question of what was to be done with the emancipated slaves was, to “do nothing with them.” “Your doing with them is their greatest misfortune,” he lectured his fellow countrymen; “just let them alone.” Slavery, he implied, had always been a measure of avaricious, powerful people “doing” too much with and to black people. In language modern antigovernment conservatives, including Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas, have loved to appropriate and rip out of historical context, Douglass gave his prescription: “If the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall. . . . Your interference is doing him positive injury.” In 1862, Douglass expressed doubts about the freedmen’s relief efforts, although within a year he went on the lecture circuit to raise money for just such organizations and even donated his speaking fees to the cause. Wishing for a world of fairness and merit early in the struggle, however, Douglass denounced what he oddly called the “old clothes system of benevolence.” He did not want the freed slaves to “depend for their bread and raiment upon the benevolence of the North,” arguing, naïvely in retrospect, that the freedmen would make it on their own if left alone.20

Emancipated slaves undergoing terrible hardships dearly needed to gain self-respect. But their need for food, clothing, medical care, and protection quickly became even more necessary. Douglass’s insensitive remarks about Northern benevolence were shortsighted and misplaced at best. Later, in the 1870s, Douglass would preach a black self-reliance and a laissez-faire individualism that echoed the reigning Social Darwinism of the day, and which may always have roiled under the mental surfaces of this proud, putative self-made man. Such contradictions emanated from deep in the psychological well of a man who had so long himself relied on the financial benevolence, as well as the emotional support, of influential and wealthy white reformers as well as the fund-raising campaigns of his devoted British female friends. No one ever worked harder, nor at greater risk, for the liberation of American slaves than Douglass. But he had processed hard psychic lessons for years about loving and hating the hands that feed one’s family, buy one’s freedom, help educate one’s children, and keep the printing press rolling.21 During the slaughter and displacement of the war, however, he soon found that the fate of the freedmen was a much more complex problem than the “do nothing” rhetoric had implied.

The tension between the doctrine of self-reliance and the necessity of government support for the freedmen produced a working paradox in Douglass’s thought throughout the war and postbellum period. He never stopped arguing that the legacy of slavery would require federal aid to the freedpeople, but he also never surrendered his commitment to a fierce individualism. As both belief and strategy, he advanced both doctrines at once, a position of stark contradiction after the war in an age decreasingly receptive to humanitarian reform. While expecting a rugged self-reliance from his people, so many of whom emerged from slavery with little or no human or physical capital, he also demanded justice and fairness from the nation. In 1862 Douglass warmly called the government the “shield . . . from the fury and vengeance of treason, rebellion and anarchy.” In every discussion of the welfare of the freedmen during the war, Douglass insisted that the government “deal justly” with blacks.22 Douglass assiduously advocated for both bootstraps and aid, all the while learning that among the many casualties of the total war were impulses of humane fairness.

What Douglass meant, in large part, by “do nothing” was “do justice.” Coupled with his calls for black self-help were his demands for education, wages, protection in the workplace, civil rights, and suffrage. All of these aims would require extraordinary use of federal power, new laws, military enforcement, and fundamental changes in social attitudes. He expected a great deal from revolution wrought by the war; in millennialist historical thinking, the limits of change are in God’s imagination as much as in mankind’s. “We would not for a moment check . . . the benevolent concern for the future welfare of the colored race in America,” wrote Douglass in 1862, “but . . . we earnestly plead for justice above all else.”23 But by 1863, “justice” was a many-headed, bloody dream as it underwent rebirth.

From Northerners, Douglass wanted less pity and more ballots, less benevolence and more black land ownership. He would never be comfortable with any widespread confiscation or redistribution of Confederate lands in the wake of the war. Instead, he wanted freedmen to obtain land by means consistent with the sanctity of private property, although in his view the government ought to have a primary role in securing and arranging the sale of such land. With time, Douglass applauded every function of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the unprecedented federal agency created in early 1865 to try to provide massive social welfare to the millions of black and white displaced people in the South. But when emancipation itself was still a revolutionary policy in the making, he seems to have concluded that white audiences needed strategic preparation that would feel consistent with their worldviews. “What shall be done with the four million emancipated slaves if emancipated?” Douglass asked. “Pay them honest wages for honest work; dispense with the biting lash, and pay the ready cash; awaken a new class of motives in them; remove those old motives of shriveling fear of punishment which benumb and degrade the soul, and supplant them by he higher motives of . . . self-respect . . . and personal responsibility.” Then Douglass shifted the point of view decisively; “They [blacks] have been compelled hitherto to regard the white man as a cruel, selfish, remorseless tyrant. . . . Now let him see that the white man has a nobler and better side to his character.”24 This was thoroughgoing political liberalism sprinkled with twists of old-fashioned moral suasion. It was not economic radicalism. The substance of Douglass’s message to white Americans, therefore, was morally change yourselves. The new order was as much for whites to give as it was for blacks to take.

Douglass knew that the prospect of emancipation had always needed sweetening in Northern ears, just as it had in numerous other nations and empires. The “do nothing” dictum might allay white fears; he portrayed blacks as hardworking people who only needed simple justice and a fair chance. Land ownership would would make each of them a “better producer and a better consumer.” Northerners need not fear massive migrations, vagrancy, or criminality, Douglass contended, if blacks were given equality before the law. Douglass believed blacks had been perceived as an “exception” too long, and he wanted to prevent their becoming permanent social pariahs.25 What do nothing meant, in part, was to free the slaves without colonizing or subjugating them as a racial caste; then give them equality and allow them to learn, work, and vote. Douglass demanded governmental action, not merely letting the freedmen live or die by their own pluck.

Douglass feared a “vindictive spirit sure to be roused against the whole colored race” in an imagined postwar South. He repeatedly called on Northern reformers to improve the condition of the former slaves. Whenever the shooting stopped, “the whole South,” Douglass declared, “as it never was before the abolition of slavery will become missionary ground.” Capturing the spirit of freedmen’s aid societies, Douglass urged reformers and teachers to “walk among these slavery-smitten columns of humanity and lift their forms towards Heaven.” The freedmen’s needs would require what the orator called “all the elevating and civilizing institutions of the country.”26 Modern Republicans, eager to find a black spokesman for personal responsibility, have not bothered to read deeper into Douglass.

As Douglass addressed during wartime the question of Reconstruction, he more and more stressed black suffrage. With the war nearing its end in April 1865, he gave an address to abolitionists in Boston entitled “What the Black Man Wants,” in which he outlined at length the reasons why his people needed the vote. He contended that “women, as well as men, have the right to vote,” but in the moment, women must wait for “another basis” to gain suffrage, a position that would ultimately land him in a bitter feud with many women reformers. The ballot, he believed, would serve as protection from white racism, a means of education, and a source of self-worth. Douglass treated suffrage with special urgency at the war’s end; the opportunity might never come again in anyone’s lifetime: “This is the hour, our streets are in mourning . . . and under the chastisement of this rebellion we have almost come up to the point of conceding this great, this all-important right of suffrage.” Hence, with prophetic insight, Douglass urged abolitionists to harness for all time the extraordinary forces the war had unleashed. “Judgments terrible . . . overwhelming, are abroad in the land,” he counseled. “I fear if we fail to do it now . . . we may not see, for centuries to come, the same disposition that exists at this moment.”27

• • •

Whether an abolition war could ever be waged to its conclusion was very much still in doubt in the bloody summer of 1864. The revolution could still be lost. In the election campaign of that year Douglass continued to be troubled by the ambiguous policies of the Lincoln administration. Conflicting factions within the Republican Party vied to influence and control the evolving emancipation as well as Reconstruction policies. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, the old leader of colonization, would accept emancipation of slaves in reconstructed Southern states, but opposed any political or civil rights for freedmen. He did so in fearmongering, Negro-phobic public speeches, claiming without authority to speak for the president as Blair warned against racial “amalgamation.” He traveled the North with a message as antiblack as it was antislavery. He called the abolitionists’ advocacy of equality “a fundamental change in the laws of nature . . . blending different species of the human race.” He continued to advocate for the colonization of liberated blacks to their own natural “climes” and “hemispheres.” The other wing of Republicans, the more ascendant Radicals, led by Congressman Henry Winter Davis of Maryland and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and others, wanted immediate emancipation followed by the beginnings of equality, including black suffrage. Lincoln sought above all to sustain party unity, to make emancipation a certainty, although by gradual and orderly means if possible. In late 1863, Lincoln had responded to a Michigan Republican who had urged him to move faster against the conservatives by saying that he hoped “to stand firm enough not to go backward, and yet not go forward fast enough to wreck the country’s cause.”28 This was the Lincoln who had exasperated Douglass in 1861–62, and as the war collapsed into horrible stalemate in 1864, Douglass lost faith for a time in whether he and Lincoln had ever worked from the same script.

One of Lincoln’s greatest concerns was chaos or even guerrilla race war in the South as the war ended. Douglass insisted that secure land ownership and especially the right of the freed slaves to vote would be essential buttresses against that very disorder. Lincoln feared potential white violent resistance to blacks voting; Douglass believed black Southerners would need to be armed with the vote to protect themselves. Both men would in the long run be proven right; but in what order and by what pace ought this revolution take place? On that question, they greatly disagreed; Douglass possessed his own vengeful spirit to work through, and Republicans struggled for consensus.

As the presidential election campaign of 1864 approached, Douglass found himself attracted to a dump-Lincoln movement among Radicals in the Republican Party. The most contentious question that divided Republicans against themselves was Reconstruction policy, as well as perceptions of Lincoln’s indecisiveness and conservatism. A good deal of scurrilous political ambition drove passions for a new candidate as well, especially that practiced by the treasury secretary, Salmon Chase. Chase’s desire to unseat Lincoln was a wide-open secret among the political class. Lincoln had long needed Chase for his skill as an administrator and his antislavery credentials, but fully understood that he was infected with “the White House fever.” Chase had allies, but primarily he relied on a somewhat broad discontent among Radicals with what they variously considered the president’s “temporizing” approach to slavery and the prosecution of the war. Widespread contempt also simmered under the surface because of Lincoln’s frequent “joking” habits and character. Chase, in persistent efforts to damage Lincoln, had openly complained that cabinet sessions were merely “meetings for jokes.” On policy, many Radicals objected to Lincoln’s lenient approach to reconstructing Southern states and rendering justice to Confederates. Lincoln, however, was popular outside Washington, DC, and across the North. Moreover, Chase faded from the picture by the spring and early summer of 1864 due to his own embarrassing overreach; after numerous offers by Chase to resign his cabinet position, Lincoln finally accepted the fifth time.29

A more serious challenge to Lincoln’s nomination came from a group of Radicals who touted John C. Frémont for the head of the Republican ticket. Frémont, who had been the Republican standard-bearer in 1856, collected many abolitionist supporters, including some old Garrisonians. Garrison himself, however, broke with his friends and steadfastly stayed in Lincoln’s camp. Wendell Phillips called Lincoln a “half-converted, honest Western Whig trying to be an abolitionist.” Garrison, however, believed that despite his caution Lincoln had “at one blow, severed the chains of three millions three hundred thousand slaves.” Douglass walked a fence in this politically dangerous terrain. He endorsed the call for the Frémont movement’s convention, but did not attend when it met in Cleveland on May 31 to nominate the Californian for president and John Cochrane, the nephew of Gerrit Smith, as his running mate.30

Disgruntled and painfully impatient with Lincoln administration ideas about black equality and Reconstruction, Douglass decided to join the attack. The unequal-pay controversy in the Union army burned among black troops and their communities until midsummer, and the federal government showed no disposition to grant black suffrage in such occupied Southern states as Louisiana. Even before announcing his “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction” in December 1863, Lincoln had communicated forcefully to his commanding general in Louisiana, Nathaniel P. Banks, that he desired a “tangible nucleus” of Unionist leaders of whatever number, “which the remainder of the state may rally around.” This was the kernel of Lincoln’s vision of Reconstruction—a fluid, experimental process, a part of military policy, run by the president and not by Congress, and heavily dependent on his faith in an inherent Unionism within the Confederate states. A local, loyal white elite, therefore, must not be threatened off by the prospect of black suffrage. The president’s evolving Reconstruction policies made him appear passive, or even obstructionist, to Radicals. Certainly Banks looked so as he conducted elections in early 1864 with the vote restricted exclusively to white men, and as he instituted a plan to force black freedmen to work for wages capped by the government at $10 per month. Banks’s system also included prescriptions that freedmen remain on their old masters’ plantations, in “perfect subordination,” disciplined often in the old methods of slavery.31

White and black Radicals, within Louisiana and across the North, were outraged. Some abolitionists, stationed with the army in Louisiana, condemned the Banks measures as the “reestablishment of slavery,” or the substitution of “serfdom for slavery.” As Lincoln, by and large, supported the Banks system, Douglass joined the chorus of anger and frustration. Asked to explain in May why he supported the Frémont movement, the orator laid it on the line as an uncompromising Radical. Douglass demanded “complete abolition of every vestige, form and modification of Slavery in every part of the United States.” Leaving no room for experimentation and gradualism, he insisted on “perfect equality for the black man in every state before the law, in the jury box, at the ballot box and on the battlefield.” He wanted nothing short of full equality for blacks in access to “offices and honors” in the military and the government.32

After emancipation in 1863, Douglass had hoped he would never again have to attack Lincoln. But in June 1864, he wrote a stinging public rebuke of the president. It was now a “swindle” that the federal government asked “the respect of mankind for abolishing slavery,” all the while “practically re-establishing the hateful system in Louisiana.” Douglass had tried to believe in Lincoln’s steadfastness, but now his “patience and faith” dwindled. The president had “virtually laid down this as the rule of his statesmanship,” Douglass boldly stated: “Do evil by choice, right from necessity.” He chastised Lincoln for not signing Congress’s Wade-Davis Bill, which was the Radicals’ Reconstruction plan, requiring a majority of voters in a Confederate state, as opposed to only 10 percent in Lincoln’s plan, to renounce secession and declare a loyalty oath before returning to the Union. Douglass called Lincoln’s Ten Per-Cent plan an “entire contradiction of the constitutional idea of the republican Government.” Especially incensed with Republican hostility to black voting rights, Douglass slashed away at his old targets of hypocrisy and racism. “We invest with the elective franchise those who with bloody blades and bloody hands have sought the life of the nation, but sternly refuse to invest those who have done what they could to save the nation’s life.” Most demoralizing of all, he argued, was what government policy implied for the freedman once peace arrived: “to hand him back to the political power of his master, without a single element of strength to shield himself from the vindictive spirit sure to be roused against the whole colored race.”33

From the Democrats, who were about to nominate former general George B. McClellan as their candidate, and from the Frémont third-party effort, Lincoln’s reelection was in dire trouble that summer. War weariness had never been so debilitating across the North; abolitionists remained split over whether to support Lincoln’s reelection as the casualty reports from Virginia and Georgia drove Northern morale into despair. The situation was “never so gloomy,” wrote Sydney Gay, editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard. He feared that the people would vote for any compromise or follow a “party for peace at any price, even disunion.”34 A war that might not be won for union surely could not secure the emancipation of slaves. Douglass followed Lincoln’s public utterances in these months, but he surely could not know the beleaguered president’s personal thoughts. On one compelling matter, however, they unknowingly shared a great deal—the effort to discern and explain, if possible, the place of God’s will in this horrible, unending conflict.

With differing style and scope, Lincoln and Douglass shared an outlook of millennial nationalism—America as a nation with a special destiny, fraught with contradictions, and living out a historical trajectory under some kind of providential judgment. Lincoln’s “house divided against itself” and “last best hope of earth” had long been Douglass’s nation of “shameless hypocrisy,” its “hands . . . full of blood,” but also the nation “so young,” its original “great principles” so old and profound, that it could yet be redeemed. Both men possessed pliable, deeply curious minds; and they were intellectual brooders. Both expressed ambivalence about theological orthodoxy. But neither could imagine human affairs, history itself, without the idea of an active God shaping its direction and outcomes. Both kept watch over history and worried intensely about a vengeful God’s interest in the American republic. Their individual paths to the dark crisis of 1864 were both riddled with expressions of such a religious-historical worldview. Lincoln, writes the biographer Ronald White, typically “thinks his way into a problem,” looking at all sides, and “working through the logic of a syllogism.” Douglass too loved to logically weigh two sides of an issue, and like Lincoln he possessed a well-earned respect for mystery and uncertainty. Through irony he often gave the impression that he knew precisely where he would land with a typically thunderous argument. Douglass could logically and pragmatically think his way to his truths as much as the quieter Lincoln. By 1864, both men were intellectual self-reinventions of earlier selves, and both envisioned the nation in biblical terms, undergoing transformation by fire. In late 1862, Lincoln had warned the nation, “We cannot escape history . . . the fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.” Two months earlier, Douglass, had in his own way said the same: “We are saved as by fire, we grieve with sorrow-stricken families all over the North, but their terrible afflictions and heavy sorrows are their educators.”35

As another biographer, Richard Carwardine, has demonstrated, the withering demands of Lincoln’s cruel presidency “swept [him] along to a new religious understanding.” His wartime language increasingly included claims of his “firm reliance on the Divine arm,” that he sought “light from above,” was acting with “responsibility to my God,” and that he hoped to discern God’s wishes in “the signs of the times.” Lincoln, very possibly in 1864, famously scratched on a fragment of paper what his secretaries and future historians would call his “Meditation on the Divine Will.” No better example exists, except for his Second Inaugural Address, for which this statement provides a foretaste, of Lincoln’s austere, biblically informed sense of tragedy:

The will of God prevails. In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God cannot be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war it is possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party. . . . I am almost ready to say this is probably true—that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet. . . . He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.

Lincoln’s private reflection invokes a profound sense of the costs and the tragedy at the heart of this “human contest.”36

Characteristically, Lincoln couched his emerging sense of a frightening truth in words such as “almost” and “probably.” Douglass, while sharing the same ideas, was rhetorically beyond qualifiers. Ever since his first autobiographical writing, he had conducted his own meditation on divine will. He protected his own uncertainty perhaps more rigidly by rooting it explicitly in the rhetoric of Isaiah and the Hebrew prophets. Douglass’s wartime apocalypticism breathed with Old Testament fire and justification. He frequently employed phrasing such as “the laws of God,” the “stern logic of events,” or the “tradewinds of the almighty” to give both tone and substance to his explanation of the war’s meaning. Douglass’s subject was less the shaping of policy than it was to persuade a people to rise, make holy war, and answer God’s call to repent and sacrifice. “The land is now to weep and howl amid ten thousand desolations,” he cried early in the war. “Repent, Break Every Yoke, let the Oppressed Go Free for Herein alone is deliverance and safety!” Douglass repeated his great wartime theme over and over. The “Mission” speech was his jeremiadic, prosecutorial summation. A chosen but guilty people had to suffer and reform or lose their destiny altogether. Douglass decided that his best options were to stand with Isaiah and Jeremiah and issue the warnings about God’s intentions; His people might be listening at this moment as never before.37 We do not know just how or whether Lincoln or Douglass prayed. But by late summer of 1864, both men, facing this existential predicament from different positions, solemnly pondered what course God might have in mind for this terrible war.

• • •

Lincoln’s famous public letters and addresses where he showed his commitment to emancipation may or may not have had a role in softening Douglass’s ire toward the president in 1864. But in August, Lincoln stunned Douglass by inviting him to the White House for an urgent meeting that in the view of the black leader would change almost everything once again. Lincoln’s notion to invite Douglass to Washington emerged out of his meetings during the week of August 10–17 with John Eaton Jr., a New Hampshire–born, Dartmouth-educated chaplain of an Ohio regiment in the Union army. General Ulysses Grant had appointed Eaton superintendent of freedmen in 1862, and by 1864 the minister had established a large number of contraband camps in the lower Mississippi valley. On his way to Washington that month to brief the president and the War Department, Eaton had heard Douglass deliver the “Mission” speech in Toledo, Ohio, and had conversed with him about it afterward.38

Few people understood the plight of the freedpeople on the ground in the South quite like the devoted abolitionist Eaton. In reminiscences of his meetings with Lincoln, Eaton found the chief executive’s interest in the situation of freed slaves “astonishing.” Worried about the military stalemate and the process of emancipation, Lincoln, according to Eaton, “alluded to John Brown’s raid,” openly suggesting that “every possible means” ought to be considered to maximize the liberation of slaves. The president asked about a “grapevine telegraph” that might be “utilized to call upon the Negroes of the interior peacefully to leave the plantations and seek the protection of our armies.” Here was some version of Brown’s old militarized underground railroad, the idea that almost drew Douglass to Brown’s band of ill-fated warriors. Eaton informed the president of some of Douglass’s criticisms voiced in Toledo, especially about the leniency of the Reconstruction plan, the lack of action on black suffrage, and “retaliation against cruelty to Negro soldiers.” Lincoln abruptly arose, went to a private desk, drew from a drawer, and read aloud a copy of his March 13 letter to Governor Michael Hahn of Louisiana, in which Lincoln suggested that the “elective franchise” might be extended to “some colored people . . . the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.” Defensively, Lincoln beseeched Eaton, did Douglass know about this letter? Further, could “Douglass be induced to come see him” at the White House? Arrangements were quickly made, and the Rochester orator, on the road constantly that summer, was on a train through Maryland to the Baltimore and Ohio station at New Jersey Avenue and C Street in the capital.39

As Douglass sat in the reception room at the White House awaiting his interview with the president on August 19, Douglass had a chance encounter with Judge Joseph T. Mills of Wisconsin, who was also awaiting an appointment. In his diary, Mills recorded telling the president the story of how dark it felt in the reception area. So dark that “there in the corner,” said Mills, “I saw a man quietly reading who possessed a remarkable physiognomy. I was riveted to the spot. I stood & stared at him. He raised his flashing eyes & caught me in the act. I was compelled to speak. Said I, Are you the President? No, replied the stranger, I am Frederick Douglass.” Douglass had been stared at in countless such situations before, and we can only imagine the stern eyes and proud if indignant voice with which Douglass responded to this kind of encounter. Mills found the episode so humorous that in his conversations later with Lincoln, while sitting next to him on a sofa, he told of seeing Douglass: “Mr P, are you in favor of miscegenation?” Mills recorded. “That’s a democratic mode of producing good Union men, & I don’t propose to infringe on the patent.”40 In such an exchange of stares, between an educated white jurist who supported the Union war effort, and a smartly dressed black man, reading as he waited to speak with the president of the United States, we can discern an old and enduring form of American racism still alive in parlor talk: What is that black man doing in the White House? How did he get there? We can hope Lincoln ignored the joke.

In Douglass’s second meeting with Lincoln, this time at the president’s invitation, the two had a longer and remarkably frank exchange. Douglass had not minced words out on the circuit about Lincoln, accusing him in the “Mission” speech of “heartless sentiments” and an absence of “all moral feeling” on too many questions. “Policy, policy, everlasting policy,” Douglass complained in an unveiled swipe at Lincoln, “has robbed our statesmanship of all soul-moving utterances.” Lincoln seemed aware that he now sat face-to-face with a fierce but useful critic, a situation this politician had managed many times before. Twice during their interview, a secretary interrupted to tell the president that Governor William Buckingham of Connecticut was waiting at the door, but in Douglass’s memory, Lincoln kept dismissing the intrusion and said, tell the Governor to wait, “for I want to have a long talk with my friend Frederick Douglass.”41 Forever proud of this highlight moment in his career, Douglass relished retelling it.

Lincoln quickly cut to the chase and unburdened his fears that he would not be reelected, that the war could collapse into a negotiated peace, and that, especially, emancipation would grind to a halt. Lincoln, recollected Douglass, was deeply troubled by all the attacks he received from fellow Republicans. The president looked much older than the last time they met, and he “spoke with great earnestness and much solicitude.” Lincoln, who later that day swapped a Sambo story with Mills (according to the judge), looked Douglass in the eye and asked the former slave to help him devise “the means most desirable to be employed outside the army to induce the slaves in the rebel states to come within the federal lines.” Lincoln sought Douglass’s advice on how he should answer his critics, and especially on how to usher as many slaves as possible out of the border states into freedom and security before the election and the president’s potential defeat. As Lincoln talked, Douglass must have leaned forward with a stunned visage; he saw in the president “a deeper moral conviction against slavery,” he later said, than he had ever imagined. In Douglass’s retelling, Lincoln asked the former coconspirator of 1859 who had fled America for his life, “to undertake the organizing of a band of scouts, composed of colored men, whose business should be somewhat after the original plan of John Brown, to go into the rebel states, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.” Douglass listened with “profoundest satisfaction,” and perhaps even disbelief.42

Overnight, it seemed, Douglass had gone from frustrated outsider and fierce critic to special presidential adviser and organizer of a radical military mission, the purpose of which was to destroy as much of slavery as possible before political fortunes changed. We cannot know what Douglass felt in his heart that morning as he looked into Lincoln’s eyes, nor can we know fully how the old prairie lawyer processed this irony-laden moment. For those hours at least the former slave from the Tuckahoe and the Indiana dirt farmer’s son were making a revolution together.

After leaving the White House, Douglass returned to the home of a black friend with whom he stayed while in Washington. Eaton met him there and found the black leader pacing in a parlor in “a state of extreme agitation.” Douglass was both thrilled and troubled. The plan he had just agreed to help Lincoln and the army implement was inchoate and daunting. It also meant that the legitimacy of the Emancipation Proclamation was utterly dependent on military success, and therefore on the election. Douglass felt exhilarated to have been “treated . . . as a man,” and with no thought of the “color of our skins” by Lincoln. But frankly, he had little idea of just how to lead the plan to infiltrate the South, inform slaves, and funnel them north to safety. Suddenly, the man of supreme eloquence and hard rhetoric had to think about policy, organization, and clandestine logistics. Eaton said Douglass already had pen and paper on a table nearby, preparing to draft a memorandum to the president. A day or so later, before leaving the capital, Douglass received a White House messenger, accompanied with a carriage, inviting him to join Lincoln for tea out at the Soldiers’ Home, the presidential summer retreat within the District of Columbia. The orator had a speaking engagement and had to turn down the invitation, something he would always regret, especially after the terrible events of the following April.43 We do not know what Lincoln had in mind for discussion at that tea.

On the very day Douglass met with Lincoln at the White House, Julia Crofts wrote from England, full of anxiety over “all the wretchedness & misery & blood-shedding” of the war, and begging her old friend to “not go toward Washington during this time. . . . Your life is one that would be sacrificed at once if you ever reached the hands of those southern tyrants.” By the time Douglass read that letter, however, he had already drafted an outline of a plan for the president. On August 29, the old editor sent his four-part proposal for a general agent (himself presumably); subagents, selected by Douglass, stationed in various densely populated slave areas of rebel states conducting “squads of slaves” into the North; close ties and clear orders between commanding Union generals and subagents; and finally, proper provisions of food and shelter for all freedmen swept up in the liberation scheme. For himself, he wanted a “roving commission,” giving him full legitimacy amid the army officers throughout war zones. This was Douglass’s best effort at a formal proposal for the militarized underground railroad in the midst of all-out war. He told Lincoln that he had consulted several other black leaders in the mere week since their parley; all believed in the wisdom of the idea, he reported, but only some thought it practicable. Although willing to lead such an operation, it is unlikely Douglass felt much practical enthusiasm for it. Just how he would coordinate his “band of scouts,” as he later called the idea, he never made clear.44 Soon, events rendered the entire scheme unnecessary.

On September 2, the day the Democratic National Convention in Chicago nominated George McClellan for president, news flashed across the country of the fall of Atlanta to General William Tecumseh Sherman after a long siege. Just as the Democrats met to declare the war a failure and crafted a platform that would lead to a negotiated Confederate independence of some kind, Sherman famously sent a telegram to Washington: “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.” Confederates’ rising hopes plummeted, and many war-weary Northerners, represented by the famous New York diarist George Templeton Strong, saw victory now on the immediate horizon: “Glorious news this morning—Atlanta taken at last!!! It is . . . the greatest event of the war.”45 The Democrats’ peace platform put Lincoln’s apparent moderation in a different light; and Douglass had seen a devotion in the president’s heart and mind.

By late September, Frémont withdrew from the race and the choice simplified. “When there was any shadow of a hope that a man of a more decided antislavery conviction . . . could be elected, I was not for Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass wrote to fellow abolitionist Theodore Tilton. “But as soon as the Chicago [Democratic] convention, my mind was made up, and it is made still. All dates changed with the nomination of Mr. McClellan.” Like other abolitionists, Douglass wanted to actively campaign for Lincoln’s reelection. But sensing the clear Republican desire not to be identified as the “N-r party,” he stayed away from the political stump. Some things had greatly changed and some had not. “The Negro is the deformed child,” Douglass complained to Tilton in September, “put out of the room when company comes.”46 The orator still had to find his own psychic balance between the high of the Lincoln interview in late August and the low caused by the subtle and blunt indignities of Republican cold shoulders in September. For now those racist stares were not as important as winning the war and achieving universal emancipation and the right to vote.

But the school of affliction was hardly over. As Douglass had learned so many times, in the election campaign and its historic aftermath down to the end of the war and beyond, he had to keep rethinking the tragic wisdom in Job. The Lord not only giveth and taketh away, but history itself, even in its most convulsive leaps forward, giveth and taketh away.47