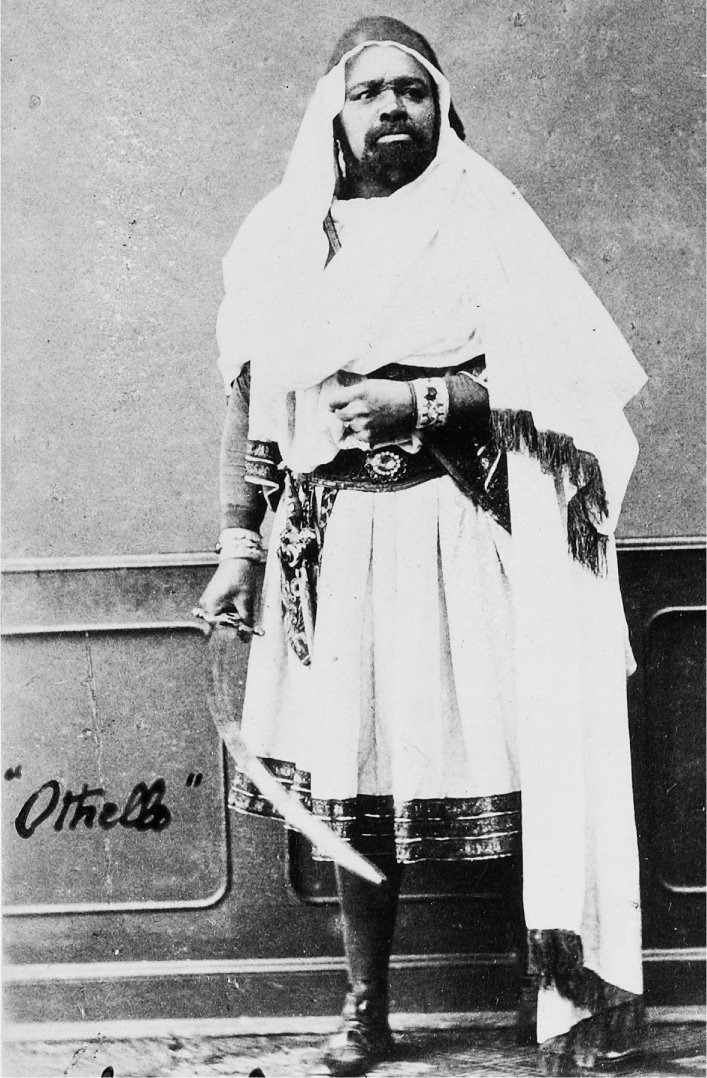

Ira Aldridge, famed Shakespearean actor, as Othello, c. 1870, postcard.

But where should I go, and what should I do? . . . A man in the situation in which I found myself has not only to divest himself of the old, which is never easily done, but adjust himself to the new, which is still more difficult.

—FREDERICK DOUGLASS, 1881

On the eve of the war, Douglass was a frustrated leader of an enslaved people, considering emigration, and entirely closed out from Republican Party power brokers. Four years later, slaves, with joy and hardship, had experienced varying degrees of emancipation, and black soldiers were stationed across the South. President Lincoln and other Republicans had sought Douglass’s counsel. By any definition a revolution had rolled over America. A new era in the nation’s racial history had begun, though few could envision the nature of its struggles.

The future of that revolution left Douglass facing enormous personal and intellectual dilemmas. Just what did emancipation mean? Where was the stricken, devastated nation headed? Where in history, philosophy, or prophecy could he find guideposts to help shape a new national order? Would the freed slaves achieve civil and political rights, and would they be protected by the government that had helped to free them? What’s more, how would the drumbeating war propagandist, visionary of an apocalyptic struggle for black freedom and the destruction of white slaveholders’ civilization, convert overnight into new roles and vocations? What would he do after abolition? What would his soldier-veteran sons do with their lives? How would he, the family patriarch, support his extended and growing network of kinfolk? What would become of a troubled marriage now that all of Anna and Frederick’s children were adults starting their own families?

Douglass had ceased editing his newspaper in August 1863—that professional-emotional stem of his life for sixteen years as a radical abolitionist. Although many others had earned the label, no African American had taken on the mantle of “leader” quite like Douglass. That leadership had been rooted in the power of words. How would he now employ his incomparable voice? Who would be listening? If you have been the scorned outsider, what do you do if the door opens and they let you take the first steps inside? What does a radical reformer do if his cause triumphs?

In Life and Times in 1881, while reflecting back on the immediate aftermath of the war, Douglass admitted that “a strange and, perhaps, perverse feeling came over me.” Great “joy” over the ending of slavery was at times “tinged with a feeling of sadness. I felt that I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life; my school was broken up, my church disbanded, and the beloved congregation dispersed, never to come together again.” Antislavery had “performed its work,” its leaders no longer had the society’s attention. The huge audiences might never come back; the endless calls to lecture might cease. So Douglass drew from a scene in a Shakespeare tragedy to express his memory of that moment: “Othello’s occupation was gone.”1 For a few years he would struggle with this sense of personal displacement and fear of irrelevance.

Othello was the “moor of Venice” who was in love with a white woman and a powerful man losing his bearings. Douglass surely read the text of the play and felt an affinity for its sense of lost authority and professional purpose. He was amply aware that in comparing himself to Othello he invoked one of the most potent symbols of racial and sexual mores in Western culture. Shakespeare’s original Othello was of noble royal origin, a former general of great battlefield achievement, and black. He marries the beautiful young Venetian woman Desdemona. Iago, who has been to the wars with Othello, is his trusted friend. The central drama, however, is how Iago in reality is the coy, vile villain, hates Othello, and slowly renders him distressed and confused, then finally poisoned by jealousy and murderous revenge because of Desdemona’s alleged infidelity with Cassio. Unaware of Desdemona’s innocence and Iago’s perfidy, the fated Othello kills his wife on her bed and, after the horrible, twisted discovery of the truth, kills himself as the confessed “fool” and is cursed by others as the “damned slave.”2

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, moral questions about the passion of jealousy, betrayal, or a woman’s alluring nature informed American reactions to Othello. But by the antebellum era, the Moor’s color and the matter of interracial marriage dominated the meaning of the play. From the 1820s, Othello was still widely staged, including in the South, but the lead character was increasingly lightened, even whitened or portrayed as tan or as a slightly swarthy American Indian. The “sooty Moor” would no longer play for racist American audiences, even in the North. If Othello appeared as a mulatto or an octoroon, as he quite often did in these highly racialized times, the lesson most Americans took was that whites and blacks ought never to mix.3

In May 1869, at the brand-new Edwin Booth Theatre in New York, Douglass attended a performance of Othello with Ottilie Assing and a group of her German friends (with the famous Booth, the assassin’s brother, in the lead role). We do not have Douglass’s reaction to the night at the theater, but Assing called it a “magnificent evening . . . where we saw an amazingly beautiful performance of Othello.” She thought Booth a “splendid Othello.” Booth recrafted and produced his own Othello, published that year and premiered in his splendid new theater, complete with frescoed ceiling and statuary, at Twenty-Third Street and Sixth Avenue. The play Frederick and Ottilie saw was Booth’s own. He had performed Othello for two decades by then, with his character wearing glittering Persian gowns, a purple-and-gold turban, speaking in a genteel, formal manner, and thoroughly purged of any taint of blackness. He was exotic and charismatic but certainly no longer the African with a violent warlike history, craving and possessing the white aristocrat’s daughter. Some lines that explicitly invoked race were even expunged from Booth’s text.4

Whatever endured in Douglass’s mind and memory from that 1869 evening of seeing Booth’s Othello, all we know is that he turned to the noble Moor’s anguished soliloquy about lost masculine dignity and mental collapse as Douglass remembered his own professional and personal displacement in the wake of the Civil War:

What sense had I of her stol’n hours of lust?

I saw’t not, thought it not, it harm’d not me. . . .

He that is robb’d, not wanting what is stol’n,

Let him not know’t, and he’s not robb’d at all. . . .

I had been happy, if the general camp,

Pioneers and all, had tasted her sweet body,

So I had nothing known. O, now for ever

Farewell the tranquil mind! Farewell content!

Farewell the plumed troop and the big wars

That make ambition virtue! O, farewell,

Farewell the neighing steed and the shrill trump,

The spirit-stirring drum, the ear-piercing fife,

The royal banner and all quality,

Pride, pomp and circumstance of glorious war! . . .

Farewell! Othello’s occupation is gone!

It is possible that, like many other Americans, Douglass loved Shakespeare as much for the rhetoric and oratory as for the literature.5 But he could not have read Othello without reflecting on its deep probings of the ideas of trust, fate, status inside or out of the state, human evil, and interracial relationships. Douglass may have been saying “farewell” to his “big wars” in the late 1860s as well, but endless smaller ones, in his public and private life, had only begun.

• • •

In the early Reconstruction years, Douglass did consider a variety of career and personal options. In 1865–66, feeling in flux, he may at least briefly have contemplated an old urge to retreat to a life of farming if he could secure the right land. It is doubtful that he entertained such an idea for long. In Rochester, among Amy Post’s correspondence, emerged the rumor that Douglass was planning to move to New Jersey (to be with Assing?). Salmon Chase, among others, invited Douglass to relocate to Alexandria, Virginia, to edit a new paper, to which he responded that he had no desire to “court violence or martyrdom” by going to the former slave state. He did apparently have new “Baltimore dreams” and gave some thought to moving to the town from which he had escaped from slavery. As the war ended in spring of 1865, Douglass confided as much to Julia Crofts in England, who still devotedly raised money and sent it to her old friend for freedmen’s aid. In other letters he admitted his desire to meet Thomas Auld again, and more important, he had already experienced a hero’s welcome in Baltimore and would again in September.6 Along with his sons, he may have imagined business opportunities in the postwar port city with a large black population.

So worried was Crofts about Douglass’s plans that she begged him not to move: “Pray very dear friend, stay in the northern states & leave Baltimore an untried field of labor—do not throw your valuable life away venturing near the old house—think of realities & let those romantic visions remain in abeyance.” She believed Douglass would be a “marked man” in Baltimore or anywhere in the South and pleaded with him not to even visit for lectures in the city of his slave youth. Indeed, Julia had reason to worry. In the wake of Douglass’s speeches in Baltimore in late 1864 or early 1865, an Augusta, Georgia, newspaper reported on his performance: “This saucy negro, one of the ‘representative men’ of the North, delivered the subjoined address at Baltimore. Poor old Maryland! She has had bitter pills enough, but here is something in the way of a black draught.” So constant was Douglass’s advocacy for black suffrage, and so eager was he for some kind of foothold inside power, that any withdrawal to a quiet life, or a long-term adventure in Europe with Assing, was never his desire.7 After the war Douglass still wanted to affect history and not be merely one of its symbols.

In May 1865, the “black draught” joined his old friends and rivals at the thirty-second-anniversary meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York. The society engaged in an intense dispute over whether to disband in the wake of emancipation—to declare victory and fold its tent. Garrison, backed by a few loyalists, led the effort for dismemberment, declaring it “an absurdity to maintain an antislavery society after slavery is dead.” But Wendell Phillips led a larger faction, outvoting Garrison 118–48, and urging the society to work for black civil and political rights. Called on to speak, Douglass reflected with nostalgia on his first years out on the circuit with the old Garrisonians, but committed himself to the much “good antislavery work” yet to be done. He made an especially forceful case for the right to vote. “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot,” Douglass asserted. As long as the word white could be inserted or even implied in new Southern state constitutions, abolitionists had not lost their occupation. Stay the course of faith and devotion, Douglass counseled, quoting Exodus when Moses pleads with the people to believe that God will yet save them from the Egyptians: “Stand still and see the salvation of God.” With Moses in the original Exodus, Douglass asked his audience for an almost unattainable faith. Believe, he exhorted, God’s promise: “The Egyptians whom ye have seen today ye shall see them no more forever.” But he urged against any naïve trust of their former enemies in the proslavery South. “Think you that because they are for a moment in the talons and the beak of our glorious eagle, instead of the slave being there, as formerly, that they are converted?” Abolitionists, Douglass argued, “had better wait and see what new form this old monster will assume.”8

By September, Douglass was back in Baltimore for a special occasion, the dedication of a “Douglass Institute,” a cultural-educational enterprise founded in a building of the former Newton University. The structure, on East Lexington Street, occupied by eight hundred people at Douglass’s address, had been appropriated by the US army as a hospital during the war.9 For this yet another extraordinary homecoming to Baltimore, Douglass crafted a beautiful address about the nature of education, civilization, and lives characterized by pursuits of the mind and soul and not merely by laborer’s brawn. From a man with no formal schooling it was a moving embrace of intellect as well as an astute analysis of the history of racism.

In an effort both sobering and hopeful, Douglass rejoiced in having his name associated with such a “first.” That blacks had rallied with some white benefactors to create an educational effort such as this was a “first sign of rain after a famine . . . the first sign of peace after ten thousand calamities.” Douglass spoke in personal as well as collective terms of learning and overcoming the “chains of ignorance” imposed by centuries of slavery. That black people had been “shut out for ages from the arts, from science, and from all the more elevating forms of industry, [or] the higher wants and aspirations of the human soul,” was, Douglass believed, “a great fact” of their history. Hence, this new beginning was a sacred act of human striving. Douglass wished that separate black schools and associations were not necessary. But he accepted their reality and used them as the source of a brilliant critique of racism.10

Black “representative . . . distinguished men” were always considered “exceptions,” Douglass complained. Claims of black racial inferiority had over time been met with historical arguments about the achievements of ancient African civilizations in Ethiopia and Egypt or in the modern revolution in Haiti. Moreover, even pointing to the three centuries in which “Christendom” had “summoned heaven and hell” in forcing African peoples through the cruel filter of the slave trade had not converted the growing ranks of racial theorists. “Our history has been but a track of blood,” said Douglass, and “mankind lost sight of our human nature in the idea of being property.” He then lamented as he celebrated that black soldiers in the Civil War had proven “at least one element of civilization . . . manly courage, that we love our country, and that we will fight for an Idea.” White civilization, Douglass argued, had for too long denied black people the fundamental element separating humans from all other animals—“consciousness,” the capacity to discern, write, and transmit history. Douglass asserted for his people the same powers of all other men: “He learns from the past, improves upon the past, looks back upon the past, and hands down his knowledge of the past to after-coming generations.” The former slave with no degrees wanted any such school as the Douglass Institute to be a place from which enlightenment and refinement in all their forms “shall flow as a river, enriching, ennobling, strengthening, and purifying all who will lave in its waters.”11 In such an assessment of what it meant to be human, Douglass sang out a kind of freedmen’s dream, as he also showed that he had found at least a piece of Othello’s postwar occupation.

• • •

In the early years of Reconstruction, Douglass did settle into what he called “a new vocation . . . full of advantages mentally and pecuniarily.” He was still very much sought after as a lecturer, usually accruing $100 per night. His most common speech was “Self-Made Men,” crafted first before the war and now in frequent demand after the conflict.12 But Douglass’s subjects were also very much about Reconstruction, the nature of “the races,” freedmen’s rights, especially suffrage, and the increasing violence against blacks in the South. He also sought and received invitations to speak in Washington, DC, at the center of the political tempest over Reconstruction. He missed his newspaper, but he now had easy access as a writer to several national journals such as the Atlantic, the North American Review, and the Independent. Douglass saw Reconstruction and its unprecedented challenges as a continuation of the purpose of the war, a sacred responsibility to the Union dead and to 4 million freed slaves. He also began to take a particular interest in American foreign affairs, especially in how a new United States—his nation now—might export its emancipationist vision to the Caribbean and elsewhere. The old abolitionist was now a nationalist, and an emerging internationalist.

Douglass’s vision of Reconstruction fell squarely into the Radical Republican camp. Especially after congressional Republicans locked horns in political and ideological warfare by 1866 with President Andrew Johnson for control of policy, Douglass grasped how “radicalism, far from being odious, is now the popular passport to power.” He believed the establishment of a new order in the South, especially the protection of the freedmen’s rights, had to be done by activist, interventionist federal power. Douglass advocated what he called “something like a despotic central government” to vanquish, as much as possible, the tradition of states’ rights. In a statement that went to the heart of the eternal American dilemma with federalism, the new doctrine of “human rights,” he maintained, could not prevail “while there remains such an idea as the right of each state to control its own local affairs.”13 This old radical had found his own passport to power.

Douglass believed slavery itself still lurked everywhere in the South, and like an incipient disease, it would infest all aspects of life if not once and for all killed. He saw Reconstruction, as he had the war, through an apocalyptic historical lens. The “fiery conflict” had made possible the “national regeneration and entire purification” of the country, he wrote in 1866. But only if “authority and power” were exercised on the defeated South to render the “deadly upas, root and branch, leaf and fibre, body and sap . . . utterly destroyed.” Douglass wanted the former Confederacy occupied and remade, with the former slaves as the central agents of a political and social revolution. In the early stage of the process, he nurtured the liberal faith that the franchise could protect the freedpeople from the coming retribution of the white South. His was a vision of the war and Reconstruction as redemptive tragedy, not unlike Herman Melville’s 1866 plea: “Let us pray that the terrible historic tragedy of our time may not have been enacted without instructing our whole beloved country through pity and terror.” While Melville wrote with bereaved wonderment about the scale of the tragedy and the harrowing tasks of Reconstruction, Douglass exuded a millennial hope. To him the war had been an “impressive teacher . . . an instructor,” and in the end “society is instructed.”14

But this moral sense of history had to be enacted in policy and against formidable foes. Douglass learned this quickly about the new president, Andrew Johnson, and the ex-Confederates the Tennessean enabled. From humble origins, Johnson was a successful stump politician from east Tennessee. He had held nearly every level of political office by the late 1850s: alderman, state representative, congressman, two terms as governor, and US senator. Johnson was the only Southern senator from a seceded state who refused to follow his state out of the Union in 1861. In 1862 Lincoln appointed him war governor of Tennessee; hence, his symbolic place on the ticket in the president’s bid for reelection in 1864. Although he opposed secession, Johnson was, nevertheless, an ardent states’ rightist. He shared none of the Radical Republicans’ expansive conception of federal power, and he was a staunch white supremacist who accepted the end of slavery but could not abide the idea of black civil and political rights. His philosophy toward Reconstruction rested in a slogan: “The Constitution as it is, and the Union as it was.”15

Congress had recessed shortly after Johnson was sworn in after Lincoln’s death. So during virtually all of the rest of 1865, the new president’s lenient, rapid, presidential, and largely pro-Southern approach dominated what historian John Hope Franklin once called “Reconstruction, Confederate style.” By September, when Douglass gave his speech in Baltimore about humane education and the nature of racism, Johnson had initiated a generous policy of pardons to ex-Confederates. Johnson also returned a good deal of confiscated and abandoned lands to their former white owners in the South, while he also did his best to thwart the work of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the agency established to provide rations to hundreds of thousands of black and white war refugees as well as adjudicate new labor contracts for freedmen. In December, as Congress reconvened, Johnson declared Reconstruction complete eight months after Appomattox. The former states of the Confederacy had all drafted new constitutions and passed a wide array of “black codes,” restricting freedmen’s lives. It seemed to many, Douglass certainly, that blacks were being returned to servility, and no one would be held responsible for the war as many former Confederates were elected to serve in Congress. Hence, his fears stated back in May that if left to their own devices, white Southerners, “by unfriendly legislation, could make our liberty . . . a delusion, a mockery.” At Baltimore in September he warned about “the persistent determination of the present Executive of the nation . . . to hold and treat us in a degraded relation.”16

Douglass saw Confederate Reconstruction coming, but was still shocked by its brazen effrontery. Congressional Republicans called an immediate halt to presidential Reconstruction in late 1865 and early 1866. Congress devised the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, with fifteen members, twelve of whom were Republicans, which in January and February conducted extraordinary public hearings to investigate the conditions on the ground in the South. These unprecedented hearings heard the testimony of 144 witnesses, including Union army officers and Freedmen’s Bureau agents; the ex-Confederates included none other than Robert E. Lee himself and former vice president Alexander H. Stephens, who offered a defense of secession and states’ rights. The overwhelming message of the hearings, especially from federal military and civilian personnel, was that martial law, Union troops, and the Freedmen’s Bureau were all dire necessities to quell violence and restore social order.17

Freedmen’s Bureau agents reported over and again about violence against ex-slaves, including whippings, ritualistic torture, and murders. One described huge problems negotiating wage contracts with unwilling planters, and a “general hatred of the freedmen.” Typical of Union officers’ testimony was that of General Clinton B. Fisk, who had spent the war and its aftermath in Tennessee and Kentucky. He traveled incognito from plantation to plantation, talking to planters and “negroes in their quarters.” Fisk had seen “slaveholders and returned rebel soldiers . . . persecute” the freedmen, “pursue them with vengeance . . . and burn down their dwellings and schoolhouses.” The Joint Committee concluded that allowing ex-Confederates to rule in their former states had been a policy of “madness and folly,” and it called for major legislation that would provide “adequate safeguards” for social order and freedmen’s rights.18 Later that spring and early summer, this seismic shift in Reconstruction policy and politics led to passage of a new Freedmen’s Bureau bill, the first Civil Rights Act of American history, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the midst of the hearings, and the standoff between president and Congress, various groups of black men came to Washington to lobby the legislature for their rights. Some were denied entry to the galleries, much less the halls of lobbying. In a letter to Senator Charles Sumner, signed by Douglass and his son Lewis, among many other black leaders, they declared that out of “self-respect” they would not “consent to be colonized” in the US Capitol. Douglass led a delegation of thirteen men (twelve black, including Lewis, and one white) to the White House for an extraordinary meeting with Johnson. They were not invited, but inspired by the Republican resurgence in the capital they insisted on an audience with the chief executive. George T. Downing of Washington, DC, shared the leadership and presentation with Douglass; the two had planned this effort to confront Johnson since mid-January, although Lewis played a key role as well in corresponding with the various members. Downing, a former successful hotel owner and caterer, current manager of the House of Representatives dining room, led off with a prepared statement in which the group declared the Thirteenth Amendment insufficient. Speaking for all black Americans, they demanded “their rights as citizens” and “equality before law.” Above all, they insisted on being “fully enfranchised . . . throughout the land.” Then Douglass stepped forward with formal deference. But unmistakably, he invoked Johnson’s “noble and humane predecessor” as he demanded the “ballot with which to save ourselves.” Whether he fully knew it or not, by his choice of words Douglass stoked Johnson’s anger and deepest prejudices, baiting him with what had to seem false respect: “In the order of Divine Providence you [Johnson] are placed in a position where you have the power to save or destroy us; to bless or blast us.”19

Johnson’s rambling replies stand as perhaps the worst exchange an American president ever conducted in person with African American leaders. The president took the bait in his forty-five-minute speech. Johnson self-righteously declared himself ready to be the “Moses” of the freedpeople. One can only imagine Douglass’s thoughts as he sat across the room from the president, less than a year after Appomattox, and heard him declare “the feelings of my own heart . . . have been for the colored man. I have owned slaves and bought slaves, but I never sold one.” For the moment Douglass and his colleagues suppressed both laughter and outrage. Then Johnson complained that in his relationship to blacks “I have been their slave instead of their being mine. Some even followed me here, while others are occupying . . . my property with my consent.” If the sanctimonious Tennessean had not offended his guests enough, he then threw a jab right at Douglass. He did “not like being arraigned,” Johnson spouted, “by some who can get up handsomely rounded periods and deal in rhetoric, and talk about abstract ideas of liberty.” The president brandished his fear of race war if his guests pursued their goals, coldly rebuked Douglass’s advocacy of black suffrage, and suggested that colonization was still the best option for the freedpeople.20 Douglass felt thrown back in time as though history had stopped somewhere before 1861.

Douglass tried to respectfully interrupt the host’s obfuscating rejection of voting rights, but Johnson quickly stopped him with “I am not quite through.” The president urged Douglass to consider the plight of poor, non-slaveholding whites, arguing that during slavery “the colored man and his master combined to keep him [the poor white] in slavery.” Addressing Douglass directly, Johnson asked, “Have you ever lived on a plantation?” “I have, Your Excellency,” replied the former slave. As Douglass tried to engage in a colloquy, Johnson pursued him with a nearly nonstop barrage. The guest had to listen as the president declared the abolition of slavery merely an “incident to the suppression of the rebellion” and predicted a “war of the races” if blacks got access to the ballot. Worse, Johnson insisted that nothing could ever be forced upon the majority of a community “without their consent.” When Douglass objected to this defense of states’ rights doctrine, remarking, “That was said before the war,” Johnson shot back angrily, “I am now talking about a principle . . . a fundamental tenet in my creed that the people must be obeyed.” Then, the leader of the country asked the former slave, “Is there anything wrong or unfair in that?” To which Douglass, according to the stenographer, “smiled” and replied, “A great deal wrong, Mr. President, with all respect.” With derision in each man’s demeanor, Douglass and Johnson then continued a tense, fruitless give-and-take for several minutes longer, the president making it clear he intended to have no debate and Douglass equally clear that he would not back down.21

Before leading the delegation out of the room, Douglass staked out a position. He reminded Johnson that if black life and liberty were left to the whims of Southern whites, the freedmen would be “divested of all political power.” Douglass summed up their impasse to Johnson’s face: “The very thing Your Excellency would avoid in the Southern states can only be avoided by the very measure that we propose.” The meeting could hardly have ended in a worse manner. If the black delegation felt disgusted, Johnson was livid. According to Johnson’s private secretary, “The President no more expected that darkey delegation yesterday, than he did the cholera.” As the secretary reported to the New York World, after the black delegation left the room at the White House, Johnson declared, “Those d__d sons of b__s thought they had me in a trap. I know that d__d Douglass; he’s just like any nigger, & he would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”22 Douglass met many presidents; sobering as it was, he may have perversely held Johnson’s epithets as a badge of honor.

Before the day was over, the delegation met with a group of Republican congressmen for a debriefing and signed a public response to Johnson. Drafted by the elder Douglass, dictated to Lewis, the statement did not mince words. It called Johnson’s “elaborate speech . . . entirely unsound and prejudicial.” The group rejected the president’s stance against black enfranchisement on the grounds of old hatreds between poor whites and former slaves. Blame for such animosity lay with white masters, argued the black leaders. “They divided both to conquer each.” They told Johnson they would not back down under any circumstances, reminding him, in one of Douglass’s old abolitionist maxims, that “men are whipped oftenest who are whipped easiest.” Finally, they unequivocally denounced Johnson’s embrace of colonization as a discredited, proslavery “theory” of human degradation.23

• • •

As Douglass looked about for that “new vocation” in the wake of the war, he quickly realized that the revolution of emancipation had only begun. In the epic contest over Reconstruction policy in Washington, he discovered his new raison d’être. It was not unlike his career as he had always known it. “I . . . soon found,” he later wrote in an understatement, “that the Negro had still a cause, and that he needed my voice and pen . . . to plead for it.” Before the end of the year and into 1867, Douglass took a remarkable speech on the road, “Sources of Danger to the Republic.” In cities from Brooklyn to St. Louis, Douglass skewered Johnson as an “unmitigated calamity,” and a “disgrace” the country must “stagger under.” So fearful of the situation was the orator that he went so far as to recommend a major constitutional revision, eliminating the president’s veto and pardon powers, as well as the vice presidency itself. These measures reflect as much his visceral hatred for Johnson as prudent constitutional thinking. But Douglass did leave a timeless maxim for republics: “Our government may at some time be in the hands of a bad man. When in the hands of a good man it is all well enough. . . . We ought to have our government so shaped that even when in the hands of a bad man we shall be safe.”24

A full twenty-five years into his public life, Douglass seemed to have realized yet again the nature of his only true weapon—words, spoken and written. Increasingly now, he wanted to get to the center of American political life, Washington, DC, and if possible, inside the circle of Republican Party leaders. He sought more lecture opportunities in the capital, spoke on political subjects, especially stressing the all-important matter of black suffrage. He cultivated growing friendships with congressmen and senators such as Charles Sumner, as well as with Chief Justice Salmon Chase. As a matter of livelihood, Douglass still conducted long, backbreaking lecture tours all over the country. Reconstruction was for Douglass the new cause not unlike the old abolition crusade; the revolution of Union victory and black emancipation could still be lost or won.

Douglass made no real distinction between Johnson’s white supremacy and slavery itself. A constant refrain in his postwar rhetoric was his assertion that “slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.” In this reasoning, as long as Johnson controlled Reconstruction, the war was not over. The Slave Power endured, Douglass believed, in the handful of conservative Republicans and the droves of Democrats who supported Johnson’s efforts to thwart the crucial legislation brewing up from Radical Republicans in Congress. In a private letter to Sumner, Douglass drew his line clearly. Former slaveholders should never be “trusted to legislate” about black rights. “Until Redeemers come from the pit instead of paradise, until the temperance cause can be left to rumsellers, until the morals of society can be safely committed to the care of those who habitually outrage all the decencies of life, the freedmen cannot be safely left to the care of their former masters.”25 The revolution was unfinished.

Douglass’s grueling travel and lecture schedule in 1866 may not have allowed him to follow as closely as he might have the great debates in Congress over passage of the Civil Rights Act in April and the Fourteenth Amendment in June. Invitations poured in to speak all over the North. Douglass’s son Charles, and daughter Rosetta, living in Rochester, tried frustratingly to keep up with their father’s whereabouts as they processed his correspondence during 1866–67. Itineraries indicate that on the two days after the White House meeting with President Johnson, Douglass spoke in Philadelphia and Baltimore respectively. Four days after that, February 13, he was back in Washington lecturing, followed by five consecutive days in Pittsburgh, and then immediately by a full week of engagements out in Illinois, where he spoke in the State House in Springfield. Through bone-numbing travel by railroad, he was again speaking back in Washington, DC, and its environs on March 6–10.26 The orator had hardly lost his occupation; he emerged in 1866 and 1867 as one of the most prominent itinerant spokesmen of freedmen’s rights and the Radical Republican effort to shape Reconstruction.

Douglass’s newly achieved enemies were well aware of the former abolitionist’s effective voice in the national political arena. It would have pleased Douglass to know how much correspondence arrived at the White House condemning him for his well-publicized confrontation with Johnson. A former Democratic Party cabinet official, William L. Hodge, applauded Johnson’s resistance to Douglass’s “impudence” and “attempt to cram the negro wool & all down our throats.” Another Democrat, James H. Embry, monitored the black orator’s speech in Philadelphia on February 9. Referring to him only as “Fred Douglass,” Embry said the speaker was “grossly insulting and abusive” and “gave loose rein to satire, anger and slander.” Commenting especially on how blacks and whites had shared the same platform in proximity, Embry nevertheless told Johnson not to worry. The speech was only important as being the utterance of his friends in Washington, and he merely the Mask behind which they strike.” Douglass would not have been flattered by the racist accusation sent to Johnson by a more humble Michigan supporter, complimenting the president: “You was more than a match for the great Fred Douglass. . . . Many fanatics think their Pet Douglass is far a head of Your Excellency in profound wisdom.” By March administration friends wrote to warn the president and his aides that Douglass was coming back to Washington to “excite the negroes to rebel.” By May, some Democrats called Johnson’s argument that black suffrage would stimulate race war (put forth to the February black delegation) “your Douglass argument.”27 These letters provide a glimpse into a kind of nineteenth-century parlor racism. If the old abolitionist needed a new occupation, he surely had one now—the frightening black man with brains who had penetrated the racist psyches of powerful people with words and his physical presence.

Although none had dispatched him to the hustings as their mask and he felt like no one’s pet, Douglass had more allies among Republicans than he realized. Lyman Trumbull, a moderate Republican senator from Illinois, had been a principal author of the Confiscation Acts and the Thirteenth Amendment. Now, Trumbull crafted the new Freedmen’s Bureau bill, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Douglass never developed a close relationship with Trumbull, whose political allegiances varied over time. Although both measures contained elements that disappointed Radicals, Douglass saw their enormous potential to his cause. The renewal of the Freedmen’s Bureau over Johnson’s veto brought hope to insecure former slaves in the South. The Civil Rights Act, which passed by a two-thirds vote in Congress on April 9, overriding the president’s veto, was a remarkable departure in federal power and in central-government state relations. It did not include political rights, to Douglass’s chagrin, but it created national citizenship for all persons (except Indians) born in the United States, and it identified some “fundamental rights,” as Trumbull put it, newly guaranteed to “every man as a free man.” Those rights included elements of contract law and protection of free labor. The law also stipulated that cases of discrimination were to be heard in federal and not state courts, although it lacked precision on how such a process would be adjudicated. Moreover, the law was vague in that it largely addressed public and not private acts of injustice. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was above all the first effort to breathe meaning and enforcement into the Thirteenth Amendment.28

Johnson’s strident veto message, laced with a staunch states’ rights position against all manner of “centralization” of power in the federal government, as well as with blatant white supremacy, invoking fears of racial intermarriage, caused a permanent break between the executive and the legislature, and set the stage for two years of constitutional crisis. Johnson even claimed that to extend the rights of blacks would discriminate against whites. He considered such expansion of civil rights “fraught with evil” and “made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race,” a set of notions some white Americans still cling to in the twenty-first century.29 When Douglass lampooned Johnson out on the stump, he did so with good reasons.

Douglass did not develop strong ties with John Bingham or Thaddeus Stevens in the House of Representatives. Bingham was the principal author of section one of the Fourteenth Amendment, and Stevens the most Radical among the Republican architects of Reconstruction policy, and often its House floor manager. Bingham was a Christian abolitionist and Ohio congressman who had served as a judge advocate in the Union army, as well as on the commission that tried the conspirators in the Lincoln assassination in 1865. He had entered Congress in 1854; his political career was a deep reflection of the antislavery history of the Republican Party. He believed the liberation of the slaves had forced the United States to federalize the Bill of Rights and apply it to all Americans. Bingham considered the “rights of citizenship” the same as the “sacred rights of human nature.” Stevens too embraced equality. The Pennsylvanian, already seventy-four years old and soon to die, in 1868, imagined Reconstruction as a movement to “rebuild a shattered empire . . . to plant deep and solid the corner-stone of eternal Justice, and to erect thereon a superstructure of perfect equality of every human being before the law.”30

Inadvertently, Bingham and Douglass agreed on all the basics of Reconstruction. They employed similar apocalyptic rhetoric as well as the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution honed in abolitionist circles during the 1850s. The new cast-iron dome of the US Capitol was now completed to full majesty when Bingham stood in the House chamber on January 25, 1866, and introduced the Fourteenth Amendment. He insisted that the war had made the amendment necessary, though “not without sorrow, not without martyrdom . . . not without storm and tempest . . . and fire running along the ground.” He insisted that the federal government enforce “equality” not merely as an abstraction but “in the states.”31 In the states.

Douglass closely followed the congressional debates and the Joint Committee’s hearings and its report in the press that winter. In language so similar to that Douglass had used ever since Appomattox, he observed Johnson’s “anti-coercive policy” characterized as “matchless wickedness,” and tantamount to the “surrender by Grant to Lee.” Douglass applauded Bingham’s forceful denunciations of states’ rights doctrines and his assertion of the “national authority” to enforce equality before law. Had Douglass attended congressional sessions, he would have relished Bingham’s condemnation of opponents of the amendment as “conspirators” and “prodigal rebels,” their Northern allies as “traitors whose hands are red with the blood of murder and assassination, who for four years struck at the life of its [the government’s] defenders.”32 Such words were political music in Douglass’s ears.

During the first six months of 1866 Republicans faced several great challenges. Three of them they met straight on in settled terms: defining citizenship; repudiation of Confederate war debts, including any claims to compensation for loss of slave property; and disqualification of ex-Confederates from officeholding. But three others remained historically unresolved and made the Fourteenth Amendment limited and controversial, though revolutionary. They did not settle the extent of the right to vote for black men and left women out of suffrage altogether; they did not give precision to the extent of civil rights made equal before law; and they struggled to reapportion representation of the “slave seats” given the Southern states under the “three-fifths clause.”33

But Bingham’s section one of the Fourteenth Amendment was something Douglass could embrace as a talisman; it was emancipation etched in parchment, enduring to this day as the most influential and far-reaching constitutional result of the Civil War. It attempted, on the matter of individual civil rights, to make the United States one body of people equal before law and not subject to local or state practice. At least in law, after embittered debate, when the amendment passed the Senate on June 8 by 33–11, and the House by 138–36, a second Constitution in America was born. Despite the myriad uses and abuses of the Fourteenth Amendment over time, and endless conservative attempts to thwart its egalitarianism, it is always worth remembering the enactment’s immediate roots. Without the liberation of 4 million slaves, section one could never have been enshrined into America’s legal DNA in the nineteenth century. Its two careful sentences are a resounding answer to the ghostlike language of Roger Taney in the Dred Scott case:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.34

Section one was a dream come true for old abolitionists. But as an adamant advocate of universal black male suffrage, Douglass found elements in section two of the Fourteenth Amendment that led him to oppose it during the coming year.

Black suffrage was still the greatest obstacle, even for Radical Republicans. Indeed, the Fourteenth Amendment contained sufficient ambiguity, especially about voting rights, that some Radicals opposed its ratification. Section two addressed suffrage, but extended the right to vote directly to no one. It stipulated that for whatever number of males denied the right to vote in a given state, that state’s representation in Congress would be “reduced in proportion.”35 The measure represented one of the hard-won but awkward compromises that made passage of the amendment possible in the ideological hurricane of 1866.

• • •

As Douglass barnstormed across the country from Rochester to Washington, and out to Illinois prairie towns and back again, from February until April 1866, he ferociously attacked Johnson and the conservatives. His ridicule of the president was so aggressive that occasionally a venue would refuse to allow his speech, and some groups protested his appearances. He wished that the status of blacks might be “settled” by Reconstruction legislation. But the nation, he feared, would now “leave in the soil some root or fibre out of which may spring other rebellions and other assassinations [like Lincoln’s].” If he were a “minister of the Gospel,” Douglass told a Washington audience, he would “preach . . . for six months from one text. . . . Remember Lot’s wife.”36

The story in Genesis 18–19 is about God’s awesome power to cause hopeful beginnings as well as dreadful endings by retributive justice. For their many sins, Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed by God raining “brimstone and fire” down on them. But Lot and his family are alerted to flee, then rescued and saved in the mountains, excepting Lot’s wife, who, warned not to look backward at the devastation, disobeys and is instantly “consumed” into a “pillar of salt.” On the morning after, Abraham, patriarch of the whole biblical tradition, stands on the mountain and surveys the “plain” smoldering below in utter ruin. But Lot and his daughters are saved because “God remembered Abraham,” as he had also remembered Noah after the flood. For Douglass the Old Testament was a template of pliant stories and historical lessons. In this case, the orator used the image of Abraham looking down upon the destroyed landscape to demand that Americans look down upon their own recent self-destruction, and all but unjustified survival, and remember. Desperately, Douglass announced, he “would show that nations should have memories.” As the biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann contends, this story makes us “see” the destruction we have ourselves caused, to know it, feel it, and remember it. “With Abraham,” we can then “know something urgent about God’s call to us.”37 In 1866–67 Douglass demanded resistance to Johnson and his minions; repeatedly, he urged the victorious North to hear the call of remembrance.

“FREDERICK DOUGLASS ON THE PRESIDENT’S POLICY!” shouted a broadside announcing the orator’s speech at the “Assembly Rooms” on Louisiana Avenue in Washington on March 10. Here Douglass faced an audience he relished; it included the Radical Pennsylvania congressman William D. Kelley, Senators Richard Yates of Illinois and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, and especially General Oliver O. Howard, the director of the Freedmen’s Bureau. This was the kind of political power center he sought. Douglass delivered a fierce defense of the integrity of “the Negro.” Contrary to predictions, they would never “die out,” despite ubiquitous images of them for white eyes at the mercy of “the lash, the bloodhound, and the auction-block.” Blacks had risen from the depths of generations of enslavement to the heights of respectability, and hence the nation was “honor bound” to give them the franchise. Only the vote could provide self-protection. With “considerable humor and a good deal of sarcasm,” wrote a reporter, Douglass pilloried Johnson for his racist contradictions expressed in their White House meeting. The chief executive’s anxieties about race mixing, said the former slave, ought to be assuaged since “the white man and the negro agreed well” within his (Douglass’s) own blood. “What shall be said of Andrew Johnson?” Douglass asked. Better, he concluded, to “leave Mr. Johnson speak for himself as being the most damaging thing he can do.” The president had “promised to be the Moses of the colored race,” but was readily becoming “their Pharaoh.” Then, Douglass tested the limits of propriety, saying that Johnson need not fear “physical assassination” from blacks. That would add nothing to the “refinements” of society; instead they only intended his “moral assassination.”38

• • •

Over the summer of 1866, Douglass joined forces with old abolitionist friends Gerrit Smith and Wendell Phillips and openly opposed the Fourteenth Amendment on the grounds that it did not explicitly provide black suffrage. As the pivotal fall congressional elections loomed, the Republicans were deeply divided on the question of black voting rights. Thaddeus Stevens, who was a complex mixture of idealism and pragmatic politics, urged caution on suffrage, knowing that the vast majority of white Northerners, even Republicans, would not welcome political equality for blacks any more than they would social equality. Northern votes and control of Congress against Johnson’s conservative coalition were at stake. But in this instance Douglass’s own hard-earned sense of political pragmatism dissipated. He simply could not countenance citizenship without the right to vote. In July, he made the case in the National Anti-Slavery Standard that he had made on so many platforms. “Equal” citizenship, he said, without the franchise was “but an empty name. . . . To say that I am a citizen to pay taxes . . . obey laws . . . and fight the battles of the country, but in all that respects voting and representation, I am but as so much inert matter, is to insult my manhood.”39 In 1866–67, Douglass’s political sensibilities careened between exhilaration and outrage.

Douglass also grew discouraged at the constant news of mob violence emanating from the South. Nothing tarnished the theory at the heart of political liberalism—that the vote could protect people—quite like the horrific riots/massacres in Memphis, May 1–13, and in New Orleans, July 30–31. The black population of Memphis had quadrupled during the year since the war. Hundreds of freedmen and black soldiers were now a very visible part of the city’s life. When two horse-drawn hacks collided, one driven by a white man and the other a black, and black troops intervened, violence exploded for three days. White mobs attacked black communities; when the smoke cleared, forty-eight people were dead, all but two black. Five black women were raped, and African American houses and churches, as well as Freedmen’s Bureau schools, torched. In the Crescent City, a new radical legislature, and a public procession of some two hundred black supporters, many of whom were former Union soldiers, tried to assemble. But city police, led by Confederate veterans, attacked the gathering, and gun battles broke out in the streets. Delegates and allies were shot down as they attempted to leave the convention hall under cover of white flags. The New Orleans bloodbath left thirty-four blacks and three white Radicals dead, and at least a hundred more wounded. The recalcitrant white South had risen with the vengeance Douglass had predicted.40

• • •

In August, the National Union Convention met in Philadelphia to rally around Johnson’s policies. As a symbol of the sectional reunion that Johnson wanted to declare accomplished, the South Carolina ex–Confederate senator and current governor, James L. Orr, and former Union general Darius N. Couch walked into the convention arm in arm. Appalled by this display of obeisance to the former Confederate states, and against the backdrop of broad public awareness of antiblack violence, Republicans decided to convene their own counterconvention of “Southern Loyalists” in Philadelphia. Hundreds of Northern Republicans attended as honorary delegates, including Douglass, who was unexpectedly elected by fellow party members in Rochester. Demonstrating the depth of Republican squeamishness about black suffrage and the delicacy of the fall elections, none other than Thaddeus Stevens had urged Rochesterites not to send Douglass. Flouting Stevens or anyone else arguing that a black leader should remain invisible at this juncture, Douglass departed Rochester with a public statement: “If this convention will receive me, the event will certainly be somewhat significant progress. If they reject me, they will only identify themselves with another convention,” Johnson’s.41 Douglass knew there was more than one way to wave a bloody shirt.

Douglass’s presence at the convention was the subject of controversy even before he arrived in Philadelphia. Aboard a train somewhere between Harrisburg and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a group of fellow delegates from western and Southern states approached him, expressed their “very high respect,” and then urged him not to attend the convention. The scene on that train car was one among many Douglass remembered as an autobiographer. It told something revealing about both his life and the country. He felt like “the Jonah of the Republican ship,” he recalled, “and responsible for the contrary winds and misbehaving weather.” Among the group waiting upon him was the widely esteemed governor of Indiana, Oliver P. Morton. The chief spokesman making the awkward appeal was a New Orleanian with a “very French name” that Douglass could not recall. The “undesirableness” of a black man’s presence, the group argued, was dictated by Northern racial prejudice. In the fall elections, these Republicans believed they must dodge the “cry of social and political equality” sure to be raised against them. In Life and Times, Douglass purported to remember verbatim his reply to the polite visitors: “Gentlemen, with all respect, you might as well ask me to put a loaded pistol to my head and blow my brains out, as to ask me to keep out of this convention.” He remembered, gleefully, warning his detractors that should they persist in excluding him, they would themselves be “branded . . . as dastardly hypocrites.” Not to have participated, he said, “would contradict the principle and purpose of my life.”42 Douglass had lived as a public symbol in America and abroad, but rarely had his physical presence caused such a stir in the house of his friends. Embarrassed, the Republican politicians returned to their railcars for the ride into Philadelphia.

On September 3, nearly three hundred delegates gathered in Independence Hall for a grand procession, two abreast, through the historic streets of Philadelphia. Having failed to exclude Douglass, most Republicans resolved to ignore him. Awkward and conspicuous, he stood alone as the lines formed; the delegates, he recalled, “seemed to be ashamed or afraid of me.” The tall brown man with the recognizable silver-streaked mane of hair stood out like the black sheep in the flock. To his rescue came Theodore Tilton, a friend and the editor of the New York Independent. During the parade, Douglass and Tilton’s arm-in-arm march garnered tumultuous cheers from the crowds, as well as scowls from some tense Republicans. At Ninth and Chesnutt Streets, Douglass spied a familiar face in the front line of the crowd. Amanda Sears, daughter of Thomas and Lucretia Auld, Douglass’s second owners, stood waving with her two children. Douglass had nothing but fond memories of Amanda’s mother. He broke ranks in the march and ran to Amanda, asking “what brought her to Philadelphia?” With “animated voice,” said the autobiographer, the former slaveholder’s daughter replied, “I heard you were to be here, and I came to see you walk in this procession.”43 The simpatico between the two childhood acquaintances, possible siblings, was apparent for all to see.

The Republicans’ procession became the subject of ridicule in the Democratic Party and pro-Johnson press. Moreover, Thaddeus Stevens did not attend the convention, but was sufficiently irked at what he called the “arm-in-arm performance of Douglass and Tilton” to complain about it privately. He called the image a “practical exhibition of social equality” and worried that it would “lose us some votes.”44 When he got his chance on the platform in Philadelphia, Douglass took dead aim at any such sentiments that would bar him from political life.

For three days Southern and Northern delegates met separately and attacked Johnson and the Democrats. Douglass delivered at least three speeches in the packed Union League hall. Such constant speaking in this pyrotechnic political atmosphere rendered him hoarse by the fourth day. Douglass addressed many familiar themes with raucous humor: the all-important role of the ballot in solidifying black freedom; bitter ridicule of Johnson and even scorn for allies such as Stevens; Douglass’s defense of the patriotism and assimilation of blacks to American culture contrasted with, again, the alleged retreat and decline of Indians.45

Douglass delivered a lengthy comparative, racialized rant about Native Americans. Blacks had achieved the “character of a civilized man,” and Indians had not. The Indian, said Douglass by one invidious distinction after another, is “too stiff to bend” and “looks upon your cities . . . your steamboats, and your canals and railways and electric wires, and he regards them with aversion.” The Indian “retreats,” said Douglass, while the black man “rejoices” in modernity. Brutally ignoring so much history, Douglass claimed that against his people “there is a prejudice; against the Indian none.” He complained that Indians faced only “romantic reverence,” while blacks were “despised.” It is astounding that Douglass would use race this way just as American Indians were fighting, and losing, so many western battles over their lands, and especially as the federal government, in alliance with Christian and philanthropic reformers, launched the reservation system, as well as the long effort to detribalize Native peoples. The prolonged effort of Bureau of Indian Affairs agents to achieve the forced deculturalization—“to destroy the Indian and save the man”—of Native Americans on a vast scale was a history very different from the one Douglass used to assert the cause of black rights.46 The marketplace for racism was diverse and terrifying in Reconstruction America. Even its most visible and eloquent homegrown opponent could fall to its seductions in his fierce quest to be accepted by American “civilization.”

The political context prompted from Douglass a folksy style in which he made himself the central subject. He garnered roars of laughter and applause by announcing that he had brought along “an individual that has been associated with me for . . . the last fifty years—the negro.” To which someone in the audience shouted, “Bring your friend with you!” He was, he said, the “representative” of the “black race.” He scored points far too easily with the scurrilous racial argument that blacks would never “die out like the Indian.” Douglass could be very funny on his feet. “We ask a right to all the different boxes,” he shouted, by which he clarified, the “witness-box, the jury-box, and the ballot box.” Without these rights, said the orator, his people would remain in a “bad box.” Style trumped substance in some of these performances. He even employed a new variation on his Irish joke about voting. If “a negro sober knows as much as a white man drunk,” he surely “knows as much sober as Andy Johnson in any condition you may name.” His hosts even picked up on Douglass’s manner; Theodore Tilton and William Kelley introduced him on September 5 as a “runaway slave” in the house, who had been apprehended and brought before the meeting as “the prisoner at the bar,” tried for his crime of “wonderful genius.” Douglass had become the living exhibit, as well as the ironic relief, for some Republicans in Philadelphia. He thought his hosts’ introduction a bit “jocular,” he said, but had himself set the tone.47

Not everyone enjoyed the joke. Trouble began on the fourth day when Douglass, Tilton, and Anna Dickinson, a young Quaker orator, entered the hall of the Southern loyalists. Border-state delegates opposed black suffrage and tried to force adjournment, whereas delegates from the former Confederate states, directly dependent on black votes, held out for a suffrage resolution. The decisive moments came when Douglass and Dickinson were called upon to speak. Dickinson, a mere twenty-three years old and already heralded as the Joan of Arc of the abolitionist platform, urged the franchise for blacks as a major step in human progress. Answering the familiar cries from the audience of “Douglass! Douglass! Douglass!,” the wordmaster stepped to the platform and caused a ruckus. “I responded with all the energy of my soul,” Douglass later wrote, “for I looked upon suffrage for the Negro as the only measure which would prevent him from being thrust back into slavery.” Some border-state delegates bolted the convention; meanwhile, the mass of Southern delegates reconvened the next morning, expressed thanks to Douglass and Dickinson, and endorsed black male suffrage.48

The Fifteenth Amendment was still three years away, but its momentum swung into motion at Philadelphia in 1866. Douglass reveled in the irony, as he put it, of how “the ugly and deformed child of the family” had won a “victory” over fear and expediency. He loved how his presence at this center of American politics still seemed to terrify white editors. A New Orleans reporter worried in the wake of Philadelphia that “as soon as Republicans could get President Johnson out of the way,” they would “secure a Fred. Douglass or Sumner” in the presidency. And a Pennsylvania editor announced that soon “Fred. Douglass would be president,” with “negro governments in every southern state, negro Senators and Representatives in Congress, and no bar raised against the perfect equality in society and in politics.”49 The former slave was delighted to infest the dreams of anxious whites worried about equality.

• • •

The leaders of the women’s suffrage movement also had anxious dreams in the late 1860s. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony increasingly demanded that the crusade for black male suffrage would now sweep women into the franchise as well. Douglass remained their old ally, dating back to Seneca Falls, throughout 1866. He wrote to Stanton in February thanking her for “the launching of the good ship ‘Equal Rights Association,’ ” a new organization, of which Douglass became a vice president, devoted to achievement of universal suffrage. The two pledged mutual support of each other’s cause in voting rights. He tried to soften Stanton’s potentially volatile sensitivities by telling her there had been “no vessel like her . . . since Noah’s Ark” and without the women the ark would have sunk.50

But signs of the schism to come emerged everywhere in the wake of the Fourteenth Amendment’s inclusion of the word “male.” In November 1866, Douglass spoke at the convention of the Equal Rights Association in Albany, a meeting called to advocate for equal suffrage provisions for blacks and women in the impending revision of the New York State constitution. For the audience, which included Stanton, Anthony, Lucy Stone, and a variety of old Garrisonians who supported women’s suffrage, Douglass left mixed messages. “By every fact to which man can appeal as a justification of his own right to a ballot,” he declared, “a woman can appeal with equal force.” But then he drew historical distinctions. Women should realize the dire “urgency” faced by blacks, he argued, and wait. “With them it is a desirable matter; with us it is important; a question of life and death. With us disfranchisement means New Orleans, it means Memphis.” If woman achieved the vote, Douglass maintained, she could only do so by “lifting the negro with her.”51

As their suspicions grew, Stanton and Anthony wanted to know just where Douglass stood. Anthony wrote to Douglass in December 1866, desiring to know if he would join her in the presentation to the state legislature in January. She urged him to “sacredly devote the last of the old and the first of the new year to the work.” Similarly, Stanton wrote in January with the same query about whether they would make their case to the state government “together.” Douglass did not show up at the January 23, 1867, hearing in Albany where the state Senate voted down the women’s suffrage resolutions.52 Soon, an ugly and prolonged breach developed over whether women’s suffrage and black male suffrage coexisted on the same agenda.

With decreasing numbers of allies, Stanton and Anthony were no longer willing to play second fiddle in the race for suffrage. In their arguments they aimed both high and low. Their case for women’s suffrage stemmed from deep grievances, and from a sophisticated argument about the vote as “protector” of economic, educational, and even personal security in a world that otherwise prescribed a women’s sphere. Above all they demanded equality, not merely in the abstract, but in reality. Their demands became increasingly absolutist, uncompromising. Douglass too had often viewed the vote as protector of the safety and aspirations of blacks. But Stanton, in particular, resorted to indefensibly racist rhetoric in advancing the case for women over uneducated men of any race. In 1868, she took a stand against a “man’s government,” citing a history of “war, violence, conquest, acquisition . . . slavery, slaughter, and sacrifice” under male leadership. She believed a “man’s government” is worse than a “white man’s government” by the strange reasoning that it would only “multiply the tyrants.”53

Then Stanton aimed at racial comparisons and forced Douglass and others to react. By denying American women the vote, politicians, Stanton contended, degraded their own “mothers, wives and daughters . . . below unwashed and unlettered ditch-diggers, boot-blacks, hostlers, butchers and barbers.” But she did not stop there with her invidious class and racial-ethnic slurs. She asked her readers to imagine “Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence . . . making laws” for refined, educated Anglo-Saxon women reformers. Douglass too had used his “drunken Patrick” jokes to argue for black suffrage. But Stanton and Anthony had crossed some lines. Many in the women’s rights movement were also disgusted when Stanton and Anthony denounced the Republicans and allied with white-supremacist Democrats in 1868. They did so by welcoming the support of wealthy racist merchant George Francis Train, who funded the new journal Revolution, Stanton’s ideological mouthpiece.54

Throughout this ugly debate over suffrage, Douglass maintained a remarkable grace and even friendship with Stanton, although not so with Anthony. A good deal of romance has evolved in popular memory about Douglass and Anthony, since they both resided in Rochester for so long, and in modern times a touching monument was erected of the two, depicting them having tea together. At the May 1869 meeting of the Equal Rights Association in New York, Anthony blew up and forced Douglass into an impromptu debate. Ninety percent of the large and raucous audience were women. Women had to stop stepping aside for the black vote, Anthony insisted. “Men cannot understand us women,” she shouted. “They think of us as some of the slaveholders used to think of their slaves, all love and compassion, with no malice in their hearts.” But watch out, she warned. Women were fed up with being “dependent” and demanded to earn their own “bread.” She chastised Douglass for arguing that black men needed the vote because their situation was more “perilous” than that of women.55

Anthony slashed away, challenging whether Douglass would ever “exchange his sex & color . . . with Elizabeth Cady Stanton.” Douglass tried to answer, but Anthony drowned him out with the assertion that votes for men but not women would send “fugitive wives” on the “loose” just as “fugitive slaves” traversed the landscape before the war. Declaring “we are in for a fight today,” Anthony declared for “the most intelligent first” in voting and, therefore, “let . . . woman be first . . . and the negro last.” The Fifteenth Amendment had severed the women’s rights movement for the foreseeable future, with Stanton and Anthony fighting in isolation for their absolute principle. Douglass gave as he took. He objected to Stanton’s use of such words as “Sambo,” although he tried to do so with humor. He fiercely resisted the equivalence of women’s plight with that of the freedpeople. “When women, because they are women, are hunted down in the cities of New York and New Orleans; when they are dragged from their houses and are hung from lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains bashed out upon the pavement . . . when they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads . . . then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.”56

Things only got worse as the Fifteenth Amendment passed Congress in February 1869 and became the template of disagreement. Stanton predicted that equipping black men in the South with the franchise would “culminate in fearful outrages on womanhood.” The imagined demon of the black rapist crawled into the suffrage debate, courtesy of the leader of the women’s rights crusade. As her biographer contends, Stanton was an “absolutist” more than a “strategist.” Unrepentantly, she preferred die-hard principle to political maneuver. She even came out against black men’s votes if women were denied, which is what the Fifteenth Amendment did. She proclaimed black women better off in slavery than in freedom: “Their emancipation is but another form of slavery. It is better to be the slave of an educated white man, than a degraded, ignorant black one.” In her opening address at the May 1869 convention, she envisioned the nation heading toward “national suicide and woman’s destruction” under “manhood” suffrage. The Fifteenth Amendment would create government where “clowns make laws for queens.” Stanton’s racial and social hierarchies allowed no concern for the complex logic of Reconstruction politics. Her racial and class code language cut to the bones of those who had spent their lives fighting for black freedom. The utter insecurity of black communities in the South simply did not interest her; she demanded the individual woman’s right to vote regardless of social context or violence.57

Trying to sustain civility, Douglass, who attended most of the women’s rights meetings, pushed back. Countless times Douglass gave his full support to women’s equal right to suffrage. By modern standards, he could seem rather patriarchal in his language, contending that white women had always been advantaged because their “husbands, fathers, and brothers are voters” and could protect women’s interests. His humor at women’s rights gatherings may sometimes have fallen flat, as in Rhode Island in 1868, when he remarked, “I cannot say much about woman’s wrongs. The men love them too much to wrong them.” He claimed as well that in every debate with a woman, he had “got the worst of it.” He thought women had an “inside track” to the vote over black men because “you [white women] are beautiful and we are not.”58 Douglass abhorred, however, Stanton’s and Anthony’s embrace of Train and the Democrats. He was disgusted by their racist rhetoric. Most important, he had learned an abiding pragmatism from two decades of radical activism, war, and revolution in proslavery America. He wished the Fifteenth Amendment had gone further in outlawing qualification tests and in extending the vote to women. But this was hardly the first time Douglass accepted half measures from his fellow Republicans while working for a longer revolution. He knew that political rights derived from politics and had learned it the hard way.

In March 1869, Douglass had a chance encounter on a train in Ohio with Stanton and Anthony. It was still two months before the bitter breakup. They managed a friendly ride as well as an “earnest debate.” Anthony extended her hand, although it would be one of the last times for many years to the man Stanton described in “a great circular cape of wolf skins.” Stanton’s remembrance was respectful but foreboding. She observed that Douglass had “a most formidable and ferocious aspect.” In correspondence, Stanton wrote with sharp wit. “I trembled in my shoes and was almost as paralyzed as Red Riding Hood in a similar encounter.” Douglass left her feeling “reassured” by a “gracious smile” and “hearty words.”59

The black orator seeking new vocations never truly reconciled with Anthony, who remained embittered. But he did maintain friendly professional relations with Stanton in the coming two decades. Douglass attended many women’s rights conventions in the years to come, and in 1870–71 he wholly endorsed the effort for a Sixteenth Amendment for women’s suffrage as a robust “natural” right to govern themselves in every way a man could. At the same time he counseled women to have “the patience of truth while they advocate the truth.”60 The Big Bad Wolf remained obsessed with political rights, chalked up at best a partial victory, and moved on to new crises, national and personal.

• • •

Douglass’s personal life was now fraught with many conflicting pressures. Throughout the Reconstruction years, the patriarch found himself over and again adjudicating rivalries and feuds among his children and their spouses. Everyone in his extended family struggled with money and livelihood, and Anna, still the center of the home everyone returned to in one way or another, suffered from recurring illnesses. The itinerant lecturer, needing to make a living on which all around him depended, sustained what his son Charles called the “hard and killing tours.” A long-lost sibling from slavery days on the Eastern Shore was about to arrive wondrously in the Douglasses’ lap in Rochester with his own family of former slaves in tow. Julia Crofts and the old editor sustained their transatlantic correspondence, full of nostalgia for past dreams and labors, assurances of their mutual deep “trust,” and Julia’s worries over Frederick’s occasional “despondency.” Clearly, Douglass could still confide in his old comrade, whatever the distance or subject. And Ottilie Assing, the adoring, opinionated, voluable, hidebound salon host in Hoboken, remained a presence in his life. She sustained strong views about how her occasional companion conducted his career, his family, his finances, and his political and religious ideas. Repeatedly, she also informed her sister in Italy of her desire to return to or visit Europe, but could not imagine “how I’m supposed to manage to untie myself from Douglass.”61 If anything, Othello had too many occupations.