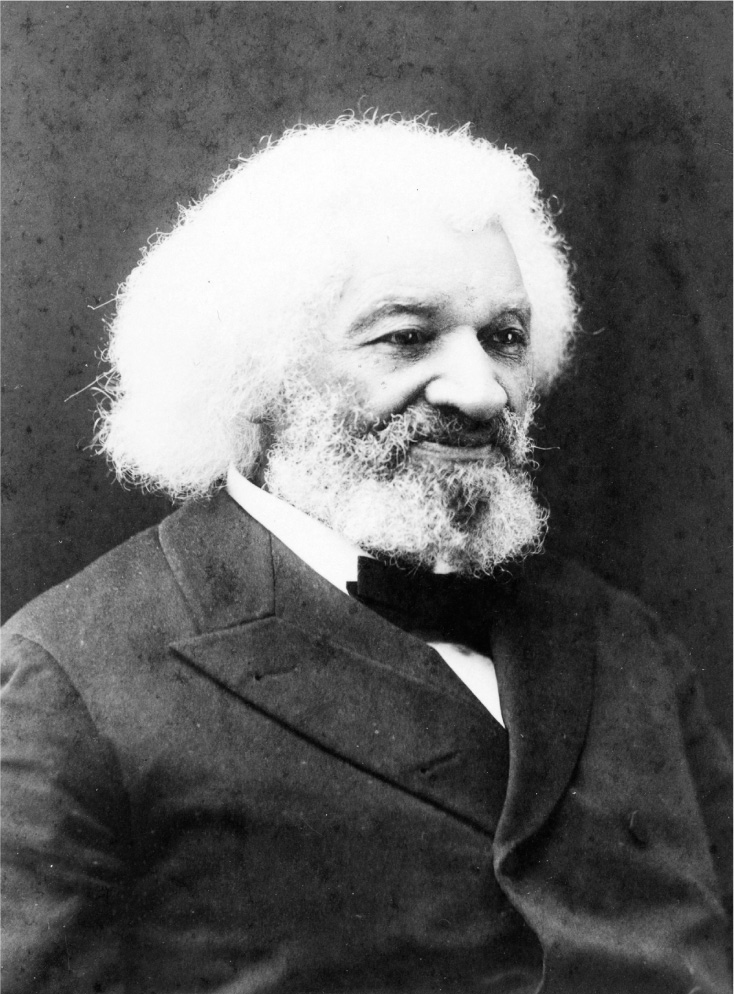

Frederick Douglass, in his library at Cedar Hill, c. 1893.

Oh, Douglass, thou hast passed beyond the shore,

But still thy voice is ringing o’er the gale!

Thou’st taught thy race how high her hopes may soar,

And bade her seek the heights, nor faint, nor fail.

She will not fail, she heeds thy stirring cry,

She knows thy guardian spirit will be nigh,

And, rising from beneath the chast’ning rod,

She stretches out her bleeding hands to God!

—PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR, “FREDERICK DOUGLASS,” 1895

Amid weariness and inconsistent health, Douglass remained astonishingly active and engaged in the last months of life. In February 1894 he wrote to old comrade Julia Crofts, “I am still alive and in active service.” Given the violence and racism that now “assailed” blacks, he fell back upon a sense of Providence around which he and Julia had long ago found common cause: “As things are, we can only labor and wait in the belief that God reigns in Eternity and that all things work together for good.” Nearly a year later, he wrote to J. E. Rankin, of Howard University, banishing any rumors that he would be interested in taking on the presidency of that institution: “I have been a long time in this world and a long time acquainted with myself, and I know . . . just what I am fit for.” On February 6, 1895, he rejected an invitation to speak on February 21 (which would be the day after his death) with the disclaimer: “I have more work on my hands than I know how to accomplish and cannot well take any more on or give promises to any more.”1 It was a time for taking stock of past and present, but Douglass never retired his pen or his voice.

Until his dying day Old Man Eloquent received an unending array of invitations to lecture, many of which he accepted. He continued to deliver the “Lessons” lecture in various forms. The extended Douglass family still provided him with joy, especially the surviving grandchildren, as well as financial and emotional travail. With son Lewis taking the lead, Douglass invested further in real estate in Washington, near Annapolis, and in Baltimore. Fame remained a serious problem; he performed repeatedly as the race’s representative man, enduring the usual slings and arrows that role entailed. His health seemed to rise and fall, and he disliked the perception that he was now an old man.2 Moreover, Douglass never stopped trying to ascertain the identity of his father and his own birthday. It gnawed at him like a hunger that could never be fulfilled.

After trying to rest at Cedar Hill through the winter following the eight-month Chicago sojourn, by March 1894, Douglass resumed his never-ending pursuit of just who he was amid all the mysteries of the Eastern Shore. While his heart still beat, the lynching crisis and the nation’s fate might wait for a moment. Douglass wrote to Benjamin F. Auld, a son of Hugh Auld, Douglass’s former owner, asking for information less about the paternity than about his accurate age. He reminisced of going to Baltimore in 1825 to be the companion of Benjamin’s brother, Thomas, and believed himself to have been eight years old then. Douglass wondered if Auld could help him “get some idea of my exact age.” He remembered amusingly that he had been “big enough to bring a good sized bucket of water from the pump on Washington Street to our house.” The search continued to the very end. “I have always been troubled by the thought of having no birthday.” He reckoned that he was “about 77 years old,” as usual one year in error. But in his assiduous search among possible kinfolk Douglass assured Benjamin how “happy” he had been to be sent back to Baltimore, to his “good home” with Benjamin’s “good mother,” Sophia Auld, after the Anthony slaves were divided.3 Douglass had to feel secure at least in his waning years to thus alter older versions of these traumas in his youth; the Aulds now appeared in memory in soft tones. The appeal turned up no new evidence. His process of always giving shape and meaning to his life’s story remained frustrated by his being unable to give it a fully factual beginning.

Over his final year Douglass gave the “Lessons” speech about lynching many times, and he received a great deal of heartening response. So concerned was the orator about the substance of this lecture, and for his delivery style now as an elderly man, that just before first giving the address in Washington, Douglass invited a friend, William Tunnell, up to Cedar Hill to listen to a dry run. Tunnell worked as a kind of press agent for the speech, visiting the Washington Post and other papers, drumming up “sympathy and interest” as well as “influential circulation.” Since his first days on the North Star in the 1840s, Douglass’s career had been in some form a marketing operation. Ida Wells also tried to sell copies of the “Lessons” speech during her second tour of England. The day after the performance in Washington at Metropolitan AME in January 1894, a worker at the Record and Pensions Bureau of the War Department, Alfred Anderson, wrote to say that it was “all the topic of conversation” around his office. He believed he had just read the “great Negro Gladstone of America.” Patients gathered in the District of Columbia Homeopathic Hospital to read the speech and begged Douglass to come visit them. Some people wrote just to tell Douglass that their entire families were discussing the speech, including their children. His granddaughter Estelle Sprague wrote to tell Douglass that at the school in which she taught in Virginia the entire student body gathered on a Sunday to listen to the young teacher read aloud her famous grandfather’s speech.4 Could an old man still living by his voice ever receive better affirmations?

Gratified, Douglass had produced for the violent and depression-ridden 1890s one of his best efforts, and it led to endless invitations from churches, clubs, schools, and colleges to speak all across the nation. He had named the problem brilliantly and laid a dagger once again into the nation’s moral heart. The disruptive, disturbing prophet of justice was back on his game. In 1893, blacks in Kansas wanted Douglass to come on Emancipation Day, September 22, and a civic club in Nebraska wanted him for a similar event on January 1, 1894. Some all but demanded that he come support their schools or communities, such as a black church in Baltimore that audaciously asked, “Will not he who has reached transcendent eminence remember the rock from which he was hewn?” His friends kept warning him about all the “self-seeking” in the world that weighed him down, but the unknown and intimately known kept beseeching him to go speak, including Susan B. Anthony and his daughter Rosetta. As the “venerable chieftain of the race,” so called by the leaders of a Baptist church in West Virginia, Douglass took in the cascade of invitations. He accepted too many. “Though I am no longer young and begin to feel the touch of time and toil,” he admitted to a friend in May 1894, “I spend much of my time in traveling and speaking.” He rejoiced in reporting that he had just addressed an audience of two thousand in Boston about lynching.5

• • •

Fame further meant that Douglass remained the target of never-ending requests for money. Begging letters poured into Cedar Hill from unknown people, friends, and family members. The family was constantly a draw on the patriarch’s bank accounts and emotions. The handsome grandson-in-law Charles Morris became a wanderer after his wife’s death, as well as a frequent correspondent in need of money. Douglass’s generosity was remarkable, but sometimes he expressed anger at how some kinfolk squandered his largess. He considered the $200 advanced to Charles to pay for his wife’s funeral “as so much taken out of my pocket for which no note or written acknowledgement was given.” Douglass chastised his grandson-in-law, who had apparently lost the money: “There is nothing that separates people more widely than the failure to pay honest debts.” On the more positive side of the ledger, the grandfather lovingly supported Joseph, Charles’s son and the violin prodigy, in his musical education and tours.6

Four granddaughters, all Rosetta’s children, worked or taught at black schools or in a federal agency: Annie in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Hattie at the Florida Baptist Academy, Estelle at the Gloucester County School in Virginia, and Fredericka at the Recorder of Deeds Office in Washington. Hattie wrote in March 1894 thanking her grandfather profusely for the $15 that had just arrived. She would have borrowed it from Uncle Lewis, she said, but “both Estelle and Fredericka had borrowed same from him.” Trying to step out independently into the work world, these young women surely had their mother’s moral support, but could not rely upon their father, Nathan Sprague, who was still a personal and financial embarrassment to the elder Douglass. In January 1894, a coal dealer wrote to Douglass complaining of a debt owed him by Nathan. After many excuses and being rejected at the Spragues’ doorstep, the coal provider wrote to Cedar Hill, “For forty years I have known and honored Mr. Douglass and I regret that I am compelled to think less of a member of his family.”7 As always, Douglass mostly suppressed his anger and absorbed these woes stoically.

To some extent, Douglass had joined a donor class. He gave money to various black schools, colleges, and churches, including to Tuskegee Institute, where he helped Booker Washington by enlisting old abolitionist friends to donate as well. He donated more than his speaking fee to Metropolitan AME Church shortly after he delivered the “Lessons” address there in January 1894. He sometimes answered money requests from ordinary people with checks for small amounts. A young black portrait artist in Illinois enlisted a friend to write to the “great chieftain among the Negroes,” asking to paint his portrait for a fee. A twelve-year-old boy in North Carolina did the same in sending his crayon drawing of the famous man. Douglass sent a $15 payment to a carpenter in South Carolina who made him a cane and then promptly asked for more money for personal support. An “orphan boy” who was “born free” in Georgia had three more terms in school and demanded, “Oh! kind sir, please do not deny me. Help me all you can.” Moreover, good friends, old and young, begged Douglass for support. Ebenezer Bassett, down on his luck in the depression of 1894 and looking for work, was “far from giving up on the race of life,” but deeply stressed at the debts he already owed Douglass. The desperate young poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who could not find work in Ohio, reported himself “well in body but not in mind”; he needed help sustaining his reputation and begged for “rescue.” Douglass’s collaborator on the Chicago World’s Fair book I. Garland Penn, his situation “urgent,” appealed openly for funds.8 Hard times caused awkward letters, strained friendships, and endless decisions on whom or what to support.

All was not stress and strain, however, in Douglass’s life during his final year. From May through October 1894 in at least three cities—Boston and New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Flemington, New Jersey—he sat for some endearing photographs. They included beautiful pictures of the patriarch with grandson Joseph (violin in hand), and with his grandson-in-law Charles Morris, standing with a hand on the old man’s shoulder. They also include the splendid images of a sitting, and portly, Douglass, and two exquisite views of the great wise face, crowned with white mane, and in one of them, smiling. In one image from May, by Denis Bourdon of Boston, the eyes almost gleam with an old fire and he seems about to utter an oracle. In a second, from October, by Phineas Headley Jr. and James Reed of New Bedford, Douglass seems about to grin his way into an amusing story. For nearly fifty years he had been photographed more than any other American of the nineteenth century. The old radical was going out with a gentle smile.9

Moreover, Douglass enjoyed the deep love and companionship of his wife, Helen; no amount of public hostility ever seems to have damaged their genuine mutual affection. Near the end of his long stay in Chicago, she wrote to him confessing that she felt “awfully lonesome” without him. Their mutual tenderness flowered in letters. “If I could take your cold and your perplexities I would do so,” Helen confided. “May God in heaven keep you and bring you safely home, and may your spoken word be like winged arrows.” Helen also wrote of her husband to other prominent people, demonstrating not only her unconditional devotion, but a certain savvy ability in promoting his image. To a New York minister who had just delivered a sermon on Douglass, Helen wrote in January 1895 describing the orator as a “witness against a nation . . . the shining angel of truth by whose side I believe he was born, and by whose side he unflinchingly walked through life.” Helen’s perception of her husband became deeply religious, prophetic by any measure of the era. In March 1895, just after returning from Douglass’s funeral in Rochester, she would write to Francis Grimké, the friend who had married them and who had written an extraordinary eulogy-essay. Helen wrote revealingly, “I used to tell Mr. Douglass that nothing in his later life was to me more wonderful than his character as a child, and it does seem as if the flaming sword of an archangel had been about him from his birth to his death.”10 Like few others, Helen had taken on the role of custodian of the legacy. In domestic terms, Douglass was a lucky man; with Helen he had found a stable intellectual and spiritual partner.

Frederick Douglass, New Bedford, Massachusetts, October 31, 1894. Phineas C. Headley Jr. and James E. Reed photographers.

The old radical also became somewhat of an art patron. In spring 1894 he combined with a wealthier friend to buy the painter Henry Ossawa Tanner’s The Bagpipe Lesson for the library at Hampton Institute in Virginia. Douglass loved not only music and art, but also modern technologies. In that last spring of his life, one evening he visited a friend, “Mr. Anderson,” at his home to listen for the first time to a phonograph. Douglass’s fascination with modernity never abated. He declared himself “amazed and wonderstruck” as he “heard coming out of that trumpet the voice and clear cut sentences of my friend Isaiah Wear” (probably Isaiah C. Wears, prominent black orator from Philadelphia). Douglass wrote a letter of gratitude and profound delight: “The phonograph brought me nearest to a sense of divine creative power than anything I ever witnessed before. It raises the question as to the boundary of the human soul, the dividing line between the finite and the infinite.” Douglass’s reaction to this machine revealed much about himself. He found “something solemn in the thought that though being dead and turned to dust a man’s voice may yet live and speak.” His reaction was genuinely spiritual: “I feel somewhat over this instrument in your hand as a man feels when he embraces religion.” The “faces and forms of our departed” were important; but “this thing makes us hear their voices.”11 We have no evidence that Douglass was ever recorded on a phonograph. But he desired nothing more than that his spoken and written voice would survive infinitely for humankind. Survive it did by other means.

• • •

On February 20, 1895, a destitute African American named Lucius Harrod wrote to the Sage of Anacostia from just down the road in Hillsdale. Harrod was feeble, in ill health, and had not worked since 1888. He had no coal for heating fuel in the winter. “I am poor and needy, yet the Lord thinketh upon me,” he wrote, directly quoting Psalm 40:17 to the great man up on the hill. “If you can do me any good in whatever way.” The letter included at bottom a PS: “Often read 32nd ch. Isaiah, 2nd v of your 1862 July.” Harrod may have remembered a Douglass speech he had read that included the Isaiah passage, but on this day of all days, to reference Isaiah, which Douglass had done so many times himself, gives a special poignancy to the moment: “And a man shall be as a hiding place from the wind, and a covert from the tempest; as rivers of water in a dry place, as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land.”12 Harrod had no idea he had suggested an apt epitaph for the man whose aid he sought.

At approximately 7:00 p.m. that evening, at age seventy-seven, Douglass fell to the floor in the front hallway of Cedar Hill, dead from an apparent heart attack. He first fell slowly to his knees, then spread out on the floor. Helen Douglass was at his side, alone. She went to the front door and cried for help. In a short while a doctor, J. Stewart Harrison, was at the stricken man’s side and pronounced him dead. The man of millions of words had gone cold and silent. He was scheduled to give a lecture that evening in a local black church in Hillsdale, and the carriage arrived just as he fell dead. Lucius Harrod never received a reply as he searched for a covert that winter from his travail.13 Douglass’s joyous and turbulent tempest was over.

That morning, February 20, Frederick and Helen had taken a carriage down into the middle of Washington. Helen went to the Library of Congress while Douglass attended for most of the day the meeting of the National Council of Women at Metzerott Hall on Pennsylvania Avenue (at the location of today’s FBI Building). May Wright Sewall presided, and Douglass sat on the platform next to his old friend Susan B. Anthony. Douglass seemed in good health through the day among the fifty delegates, although one woman later reported that he continually rubbed his left hand as though it were “benumbed.” He did not make an address. He returned home to Cedar Hill around 5:00 p.m. The news of his death spread rapidly through Washington that evening and across the country. At the Women’s Council meeting that evening Sewall announced that Douglass had died. Anthony, in agony, could not continue. The next day, with bitter opposition from Southern members, the US Senate passed a resolution, 32–25, to adjourn out of respect for Douglass.14

Within four days funeral preparations had been completed. On February 25, the memorial for Douglass was primarily a black-Washington solemn tribute to its most famous resident. After a small family service at Cedar Hill a hearse-carriage transported the oak casket down into the city to Metropolitan AME Church, where Douglass not only had been a member but had delivered so many memorable addresses. A huge mixed-race crowd gathered at the church early in the morning. Between 9:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. that day throngs of people processed by the casket, in one side of the edifice and out the other. “Quiet and orderly,” reported the Washington Post, the young and old, black and white, passed around the funeral bier. Lewis and Charles were conspicuous in organizing the procession. The church groaned to capacity, and during the nearly four-hour service to follow, “thousands” more waited and milled around outside. Five hundred seats inside were reserved, and a “wild rush” occurred for the rest of the pews when the signal came. Actress, lecturer, and journalist Kate Field attended the service. She marveled at the mixture at Douglass’s funeral of the famous and the ordinary, even if the speeches were much too long. She watched “the Moses of the black race” honored in death.15

Four members of the black Sons of Veterans stood, two at either end of the coffin, as honor guards throughout the ceremony. The actual pallbearers consisted of twelve men in uniform from the “colored letter carriers” of the City of Washington. Among the honorary pallbearers were a who’s who of black Washington, including former senator Blanche Bruce, former congressman John Lynch, hotel entrepreneur W. H. A. Wormley, and Douglass’s old friend Charles Purvis. Senator John Sherman as well as Supreme Court justice John Marshall Harlan also attended the service. A Boston singer, Moses Hodges, sang Mendelssohn’s “O Rest in the Lord,” and John Hutchinson, a survivor of the famous abolitionist Hutchinson Family Singers, who had many times appeared with Douglass, sang and chanted “Dirge for a Soldier”: “Lay him low, lay him low / Under the grasses or under the snow; / What cares he? He cannot know. / Lay him low, lay him low.”16

Among the many sermons and eulogies was one biblical tribute by the white president of Howard University, the Reverend J. E. Rankin. Rankin knew his audience. He preached on Psalm 105:17–19: “He sent a man before them. He was sold for a servant. His feet they hurt with fetters. He was laid in chains of iron. Until the time when his word came to pass, the word of the Lord tried him.” Rankin likened the youthful Douglass to the Dante of the Inferno, a man who had been to hell to find righteousness. Like other eulogists Rankin stressed the “wonderful contrasts and antitheses” of the deceased’s life. He also pointed to the theme of forgiveness in how Douglass had searched to know his slaveholding kinfolk. Those close to the altar would have noticed that among the flower displays was one from the Auld family. But Rankin framed his sermon with the story of young Douglass’s many sessions with the Baltimore preacher “Uncle Lawson.” Helen likely approved of Rankin’s theme of how the old preacher had showed the teenager “how God was girding him for that day when he was to go town to town, from state to state, a flaming herald of righteousness; to cross oceans . . . lifting up the great clarion voice, which no one who ever heard can forget.” This was funeral rhetoric, but who could resist the story of the orphan slave who would be king of abolitionism?17

The casket was taken through the streets of Washington, guarded by a contingent of 150 black Grand Army of the Republic veterans, to the train station, where it departed at 7:00 p.m. for New York City. From Grand Central Terminal the casket was taken downtown to City Hall early in the morning of the twenty-sixth. There the next morning in City Hall, where both Lincoln and Ulysses Grant had lain in state, Douglass too received such an honor for two hours. From 8:00 to 10:00 a.m. a long winding line of New Yorkers viewed Douglass’s remains in the hall’s vestibule. Promptly the New York stop ended, and soon the casket and family were on the train again across New York State to Rochester.18

All business and upper grades of schools were suspended in Rochester on the day of Douglass’s burial, February 27. Huge crowds gathered around City Hall, draped in black bunting and American flags, as the body arrived, escorted by the leaders of a local “Douglass League.” At Central Church, the largest in the city, eulogies were offered by the Reverends H. H. Stebbins and W. R. Taylor. A male quartet sang “Hide Thou Me,” and the organist struck up the old spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” A “surging mass of people,” said the New York Tribune, surrounded the church and the streets during the three hours of public viewing. Accompanying Douglass’s body to Rochester were Helen, sons Lewis and Charles, Rosetta and two of her daughters, Estelle and Harriet, and the grandson Joseph. Nathan Sprague apparently did not attend. After the church service in the afternoon, dozens of carriages followed the hearse out to Mount Hope Cemetery, and on a gentle hillside Douglass was laid to rest in the winter landscape. A year later, Lewis and Charles had their mother, Anna Douglass, reinterred from Graceland Cemetery in Washington, DC, to Rochester; she is buried between Frederick and their daughter Annie. The three living children had many years of memories associated with Rochester, some cherished and some anguished. It had never been Helen’s home. In a short time Lewis, perhaps with some help from Charles, would paste dozens of newspaper obituaries and eulogies about their father into a scrapbook. Among them was one from a California gathering at which Ida Wells gave the eulogy, and a newspaper report claiming that each son had received a $50,000 inheritance. The battle over Douglass’s estate, his will, and for Cedar Hill itself had only begun.19 On this day, though, a nation and even other parts of the world thought of inheritances of other kinds from the man who had left so much to contemplate with his voice, his pen, and his vote.

• • •

In countless speeches and in the autobiographies, Douglass had imposed himself on so many who would attempt his eulogy. As early as the very next day, long obituaries and tributes appeared in newspapers across the country. He was the “self-made” American who had conquered the greatest odds, the man of mixed race but in some ways of no race, the “serf” who had risen to the unrivaled “intellectual standard” of his people, the stunning physical presence—one of the most recognizable persons in the nation. Many eulogies drew deeply from the memoirs and recited actual scenes from Douglass’s life. The story was ready and waiting, and Americans in the age of Horatio Alger loved the tale, or perhaps especially needed it in a time when fiends with lynching ropes and torches stalked black men of lesser fame, as well as a time when banks failed everywhere, savings accounts vanished, and economic failure hounded millions. “His history has often been told,” said the Brooklyn Eagle, as it also declared Douglass “thrice an American . . . in his veins ran the blood of three races . . . the Indian, the white man, and the Negro.” Other eulogies played out this fascination with the orator’s race. The New York Times announced with certainty that Douglass’s “white blood” explained his “remarkable energy” and “superior intelligence.” A paper in Rome, New York, characterized him as the “most picturesque” of Americans, and his rare ability it attributed to that he “was almost a white man.”20

But at the center of most eulogies stood the slave who had conquered chattel bondage, this most notorious of American fates. “Sweet are the uses of adversity,” rhapsodized the Eagle. “It is the north wind that toughens the oak, not the caressing breezes of the south.” And the New York Tribune instructed its readers that Douglass “became the representative man of his race . . . by virtue of self-help . . . [and] self-education.” Douglass’s death inspired lofty language, North and South. The “world’s greatest Negro” had died, said a Springfield, Illinois, paper, and in a Norfolk, Virginia, journal the “greatest man of African descent this century has seen” passed on. The Washington Star declared the passing era the “Douglassian age” and compared the deceased as symbol to the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. Exuberant eulogists compared the fallen statesman and man of letters to Gladstone and Bismarck, Goethe and Schiller, Emerson and Victor Hugo.21

Eulogies also took on odd, mixed forms. Some papers competed with claims of possessing the last letter Douglass wrote. Some groups, such as a gathering of black Methodist preachers in Richmond, decided it would be too time-consuming to conduct a major memorial for Douglass, who had appeared in so many of their pulpits, since three to four such “men of genius” now came along every year. Some papers reprinted from other sources the claim, without evidence, that Douglass was worth $300,000 at his death. Many press reports from the white South were anything but mournful. The Wilmington, North Carolina, Messenger mocked blacks for being “anxious that Congress should prostitute itself like the Radical Legislature—by allowing the remains of Fred Douglass ‘to lie in state’ in the national capital. Why . . . what has he done to merit such attentions?” This paper dismissed the deceased as a “stirrer up of bad blood and a very diligent Government teat holder and sucker, and enemy of the South.” The North Carolinian editor cultivated common public racism by urging “white faced fellows” never to “feel that they are no better than Sambo and Cuffee.” An Oshkosh, Wisconsin, account, otherwise laudatory, could not resist pointing out that Douglass had caused “serious detraction” for his reputation by the “unnatural step” of marrying a white woman. But a Milwaukee paper quickly pointed out that Frederick Bailey’s owner had taken a black woman as his “consort” to give birth to the man in question. The New Orleans Picayune tried to acknowledge Douglass as the “most eminent” man of his race, but since he was a “half-breed,” he could never be the group’s exemplar.22 In Douglass, living and dead, Americans found a persona around which to exhibit some of their worst prejudices. But it is equally stunning how much of the country seemed to know his story.

All kinds of reminiscences flowed from articles and public memorials by people who had heard Douglass speak. Someone in every town seemed to claim that distinction. Douglass could be a man for all tastes and seasons. A Washington, DC, account admired how his “intellectuality” grew from an early “fanaticism” to more “conservative” positions. A journalist named Charles T. Congdon remembered hearing Douglass engage a hostile audience from an abolitionist platform in New Bedford. As an anti-abolitionist heckler “hissed,” the young orator pointed at the offender and launched into a paraphrase of Genesis 3:14—“I told you so. Upon thy belly shalt thou go, dust shalt thou eat, and hiss all the days of thy life.” In these tellings the hecklers always shut up in the face of Douglass’s moral and verbal power. Some reminiscences relished stories of the great man’s grace and humor. The Boston Transcript repeated the oft told tale of how Douglass so often ended up sitting alone on railcars, since no one would take the seat next to the black man. “ ‘You are occupying an entire seat,’ complained a patron. ‘I know that,’ said Mr. Douglass. ‘Well, what right have you to it?’ exclaimed the man. ‘Because I am a nigger,’ returned Douglass. ‘That don’t give you a right to two seats,’ said the man—and Mr. Douglass made room for him.” Douglass thus received credit for laughing at and changing racial habits.23

Above all, blacks in communities all across the land, in the South and the far West, as well as the North, held meetings of tribute to Douglass, often passing local resolutions of honor and gratitude. The Assembly Club of San Francisco sent a list of typed resolutions to Lewis Douglass and the family. Within a week and a half of the death a gathering in Sumter County, Georgia, produced ten such resolutions. One large meeting in Atlanta rocked with “protests” against racism and violence, while another in Tuskegee came off with propriety and good order. At the Atlanta gathering, Charles Morris, the grandson-in-law, delivered a eulogy devoted to the crisis of Jim Crow railway cars and got carried away, comparing Douglass to Jesus Christ. The black Cleveland Gazette announced a simple truth exhibited during the months of Douglass commemorations: “His life and work has been public property almost since the day of his birth. . . . The race will miss him more than it can at this time realize.”24

But Douglass was not gone; he was merely dead. New geniuses were, indeed, coming along, and two of them would utter important speeches, albeit one famous and the other obscure, that very year. Booker Washington later that fall delivered his pivotal public address, often called the “Atlanta Compromise,” at the Cotton States Exhibition. In it he called for acommodation by blacks with certain elements of white supremacy and Jim Crow in exchange for industrial education and social security. Washington would to a degree trade disfranchisement and segregation for racial peace and economic opportunity.25 Although never sharing Washington’s acquiescence with Jim Crow or any diminution of the right to vote, Douglass had long prefigured the Wizard of Tuskegee on the philosophy of self-reliance.

On March 9 in Wilberforce, Ohio, W. E. B. Du Bois, a twenty-seven-year-old professor at the black college, just returned the previous year from his extraordinary educational sojourn in Germany, gave a short, remarkable speech, “Douglass as a Statesman.” In his eulogy the Massachusetts-born and Harvard-educated Du Bois urged students and faculty not to cry out in “half triumphant sadness” at the death of their leader, but to engage in “careful conscientious emulation.” Du Bois remembered Douglass’s leadership in abolitionism, in the recruiting of black soldiers in the war, in the achievement of black male suffrage, and in civil rights. As a leader Douglass had reached for goals considered “dangerous” and all but “impossible.” He was not afraid of the American “experiment in citizenship.” Douglass had proven himself a “builder of the state” largely from outside traditional power. “Our Douglass,” asserted the young intellectual, was the man of the race, but he had also “stood outside mere race lines . . . upon the broad basis of humanity.” It had been Du Bois’s manner of thought and ambition to say whenever possible that history should make way now for a humane, learned race man much like himself.26 He seemed to understand and admire Douglass’s work and persona enough to make the model in part his own.

At the end of his speech, Du Bois offered a brief but remarkable anecdote: “The first and last time I saw Douglass, he lectured on Hayti and the Haytians and here again he took a position worthy of his life and reputation.” Du Bois honored Douglass for choosing principle over diplomacy in regard to seizure of Haitian territory when he had served as US minister. Du Bois pushed hard on the irony: “To steal a book is theft, but to steal an island is missionary enterprise.” Du Bois the graduate student was in Berlin all of 1893 and therefore did not witness the Chicago Haiti speeches. It is likely, then, that Du Bois heard Douglass speak in Boston at Tremont Temple on March 16, 1892, before the younger man departed for Germany. According to the Boston press, Douglass did indeed speak that night on Haiti and the Haitians to a full house. Du Bois needed to claim Douglass, to own the mantle, to join the national chorus of those older than him who saw Douglass. The old abolitionist had fought the “preliminaries . . . for us,” said the brilliant new voice, “but the main battle he has left for us.” We cannot know whether the fresh-faced Du Bois had felt in awe of what a Boston reporter called Douglass’s “manly bearing” on the Tremont Temple stage with his “thick whitening hair brushed back from his forehead, and his eye as keen and brain as clear as ever.” But Du Bois no doubt joined the “rounds of applause” when the venerable orator announced himself “a friend to Haiti. . . . I say I am a friend to any people who have known the yoke of slavery as I have.”27 Few people ever awed Du Bois; but Douglass may have been one of them.

Du Bois knew his Douglass well enough that only a few years later as he crafted the lyrical history in his masterpiece, The Souls of Black Folk, a reader can feel and almost hear Douglass’s words informing the text. In his chapter on Booker T. Washington, Du Bois pays an homage to Douglass, saying that the former abolitionist, “in his old age, still bravely stood for the ideals of his early manhood” and had “passed away in his prime.” In the famous second chapter of Souls, “Of the Dawn of Freedom,” a vivid, polemical account of Reconstruction, the author offered what many scholars have come to consider a “Du Boisian” form of history. His biographer David Levering Lewis calls this Du Bois’s “signature,” the compression of huge pieces of history and human aspiration into single paragraphs, images, or metaphors.28

The brooding ending of “Dawn of Freedom” argues that for America to find its soul, it had to free the slaves and now continue freeing the slaves’ “children’s children.” “I have seen a land right merry with the sun. . . .” Du Bois wrote, “and there in the King’s Highway . . . sits a figure veiled and bowed, by which the traveller’s footsteps hasten as they go. On the tainted air broods fear. Three centuries’ thought has been the raising and unveiling of that bowed human heart, and now behold a century new for the duty and the deed. The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” Significantly this tragic ending is placed between two chapters in Souls that end with ringing appeals to the first principles of the Declaration of Independence. Du Bois’s history is a prophetic demand upon the creeds of a forgetful country. In the nineteenth century, no one had laid down that prophetic demand quite like Douglass, and Du Bois knew it.29 Du Boisian history was first Douglassonian history: the problem of the nineteenth century had been the problem of slavery, revealed and written in thousands of pages and spoken from countless platforms by the fugitive from the Tuckahoe. Douglass had seen to it that his story had always provided a “raising and an unveiling”—by prophetic witness, through scars, pain, anger, unforgettable metaphors, and patriotic triumphs.

Douglass had long offered himself as Du Bois’s “figure veiled and bowed” along the highway, yet one who stood up to preach a “sacrilegious irony” about the crimes of the nation, as he put it in the Fourth of July speech. In Douglass’s great orations of the 1850s, the air also hung tainted with a fear perhaps even greater than Du Bois imagined for the turn of the twentieth century. Just after placing his people in the midst of the ancient Hebrews’ Bablylonian Captivity, Douglass announced the essential theme of his life: “My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is AMERICAN SLAVERY.” And so it always was. The abolitionist filled the tainted air with jeremiadic words and sounds. He heard the “mournful wail of millions! whose chains” clanked “heavy and grievious.” Throughout his fifty years of oratory and writing, Douglass had employed all manner of blood metaphors for the nature of African American history, none more often than the line used yet again in his Haiti speeches, which Du Bois heard: the history of black people “might be traced, like a wounded man through a crowd, by the blood.” Douglass had been the man bowed by the roadside, with a trail of blood, but then the risen slave, the free man and voice, telling the nation a history it did not wish to hear. He told it all over again in the lynching crisis of the 1890s. “My language . . . is less bitter than my experience,” he announced in an 1853 address. “I am alike familiar with the whip and the chain of slavery, and the lash and the sting of public neglect and scorn.” Speaking for the bowed figure, he argued that slavery had always “shot its leprous distilment through the life-blood of the nation.” It had always “intended to put thorns under feet already bleeding, to crush a people already bowed down.”30 Hundreds of thousands of people across the nineteenth century had witnessed or read Douglass’s story of the risen figure from the side of the road. He had striven to be both a prophet of doom and of redemption.

When Douglass died, Du Bois wrote a private poem he called “The Passing of Douglass.” He etched the date, “20 February, 1895,” and the place, “Wilberforce, Green Co., Ohio,” beneath and above his title.

Then Douglass passed—his massive form

Still quivering at unrightful wrong;

His soul aflame, and on his lips

A tale and prophecy of waiting work.

Personal, heroic, elegiac, Du Bois tried to take up a standard for the next generation.

Not as the sickening dying flame,

That fading glows into the night

Passed our mightiest—nay, but as the watch-

Warning and sending in common glory,

Suddenly flocks to the Mountain, and leaves

A grim and horrid blackness in the world.

But amid the feeling of darkness, Du Bois made Douglass his own.

Live, warm and wondrous memory, my Douglass

Live, all men do love thee. . . .

Rest, dark and tired soul, my Douglass,

Thy God receive thee.

Amen!31

For decades countless Americans had looked at and listened to Douglass; they had admired and hated him, loved, followed, envied, denounced, and tried to destroy him. Many had tried to make him their own, to control his trajectory, even his words. He had been gawked at, photographed, and studied; he had won many arguments and lost many others. People had for decades named their children for him. Eulogies reflected this range of reactions over the decades. Similar to Lincoln, Douglass offered an original American to those who sought such images; he was the sui generis former slave who found books, the boy beaten into a benumbed field hand who fought back and mastered language and wielded a King James–inspired prose at the world’s oppressions with a genius to behold. He was spiritual and secular, consummately political and deeply moralistic, romantic and pragmatic, a philosopher of democracy and natural rights and a preacher of a firm doctrine of self-reliance. Douglass provided a living symbol by his physical presence and skill that refuted all manner of racist notions and reinforced others for the ignorant and the fearful. He rose from nowhere to the centers of power, or so it had seemed. He loved power but found he could wield it only with limits and often softly. He had made vanity and pride often into weapons alongside his words; he outlasted most of his enemies, except the ideology of white supremacy, which only seemed to transmogrify into more virulent forms in his old age. Underneath Douglass’s grand dignity, deep in his soul, ran a lode of humility born of experience and a long view of history, but embedded in that soul as well was his fierce, sometimes insecure, but often magnificent quest for respect, to compete, and to conquer his foes. Embedded there as well were an insatiable intellectual curiosity and a spirituality that sustained him through many trials. And so Douglass passed, but the words, and much more, endure.

In the frightening racial climate of the mid-1890s some in the next generation of black artists and thinkers saw Douglass’s death with dark foreboding. Douglass’s young protégé Paul Dunbar viewed blacks in the 1890s as a kind of crucified people, and his mentor as their “guardian” prophet, the voice forever “nigh” and sounding forth over “the gale” of racism and violence. In his 1895 poem, Dunbar also imagined Douglass as both a warrior and a resurrected Christ figure for the race. Whatever a prophet really is, in his grief at Douglass’s death, Dunbar believed blacks had lost theirs.32

One of the most remarkable eulogies of Douglass was delivered on March 10, 1895, in Washington by his close younger friend the Reverend Francis Grimké, the Presbyterian minister who had married Frederick and Helen. Grimké especially defended his friend against all claims about his “selfishness,” that the Sage of Cedar Hill had always looked out for himself and his pocketbook. No one had ever given or sacrificed more for the race than Douglass, argued Grimké. But placed in that long address is a short, compelling anecdote about Douglass’s humanity, and especially his love of music. Three weeks before Douglass died, Grimké had been at Cedar Hill for dinner. As the meal ended, “all repaired to the sitting room,” and the old orator demanded they all sing. Grandson Joseph took the lead on the violin, and someone else played the piano. Grimké remembered poignantly, “In the singing he [Douglass] took the lead.” The guest left this unforgettable image of the host: “Standing in the doorway between the sitting room and the hall, with violin in hand, he struck up . . . ‘In Thy cleft, O Rock of Ages,’ and sang it through to the very end with a pathos that moved us all. . . . It seemed to take hold of him so.” Grimké witnessed Douglass’s spirituality in full force. “I can almost hear now the deep mellow tones of his voice and feel the solemnity that pervaded the room as he sang the words:

In the sight of Jordan’s billow,

Let Thy bosom be my pillow;

Hide me, O Thou Rock of Ages,

Safe in Thee.”

Grimké felt a “kind of presentiment that the end was near, that he [Douglass] was already standing on the very brink of that Jordan over which he was soon to pass.”33

If slavery and race were the centerpieces of American history through the nineteenth century’s rise, fall, and then resurrection of the republic, no one represented that saga quite like Douglass. As the modern poet Robert Hayden so beautifully put it:

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this beautiful

and needful thing, needful to man as air, usable as earth; when it belongs at last

to all . . . when it is finally won . . .

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered.

Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,

Not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

But with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

Fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.34

Frederick Douglass seated with grandson Joseph Douglass, who was a concert violinist, New Bedford, Massachusetts, October 31, 1894. Phineas C. Headley Jr. and James E. Reed photographers.

Douglass was the prose poet of America’s and perhaps of a universal body politic; he searched for the human soul, envisioned through slavery and freedom in all their meanings. There had been no other voice quite like Douglass’s; he inspired adoration and rivalry, love and loathing. His work and his words still wear well. What shall we make of “our Douglass” in our own time? The problem of the twenty-first century is still some agonizingly enduring combination of legacies bleeding forward from slavery and color lines. Freedom in its infinite meanings remains humanity’s most universal aspiration. Douglass’s life, and especially his words, may forever serve as our watch-warnings in our unending search for the beautiful, needful thing.