Facing Fears and Confronting Evil

I’ve been in terror of you and your dogs for over thirty years, Farmer Maggot, though you may laugh to hear it. It’s a pity: for I’ve missed a good friend.”

—Frodo in JRR Tolkien’s

The Fellowship of the Ring

Hobbits are small, and the world is big. There are monsters in Middle-earth, and most of these—indeed most everything in that world—are bigger than hobbits. Even all the hobbits together would not make an army of much significance, nor are there hobbit warlords who could stand toe-to-toe with orcs or cave trolls.

In a sense, hobbits are the children of Middle-earth. In their secluded Shire, they are blissfully unaware of the horrors and creatures that could destroy them in a day. Dark forces would’ve long ago crept into the Shire and ended its innocence had Strider’s Rangers not kept their long vigil. The Rangers, like parents sheltering young children, strove to maintain the hobbits’ isolation for as long as possible.

Because, for the hobbits, “growing up” would mean the death of something precious in the world.

It is natural for a child to be afraid of things. A healthy dose of fear keeps him from dangerous situations. Fear is an acknowledgment that something may be more powerful than oneself and that it could cause damage and should therefore be avoided or at least treated with great care.

Yet, even in the rarified preserve in which the hobbits live, some fears remain: fear of boats and drowning, fear of Gandalf’s magical fireworks, fear of Farmer Maggot’s dogs, fear of strange news from Bree. Just across the Hedge from Buckland lies the Old Forest, where there are indeed things to fear. And beyond that, the Barrow-downs, where no hobbit with any sense would ever go.

A person, young or old, who has never faced true fear does not know what he would do in a truly fearful situation. Some parts of one’s character can be revealed only in a crisis. An argument can be made that, without fear, no person can reach his full potential. Certainly that is true of the hobbits who left the Shire in Tolkien’s stories.

The greater world of Middle-earth, just like the world beyond a child’s understanding, is filled with virtuous men, women, and other beings, but also with agents of terrible evil. All of us must reach childhood’s end eventually. We must venture out from the protection of our upbringing and encounter the wide world. Because it is not inside the Shire where our true identities are to be found, but outside.

The (Hobbit) Hero’s Journey

Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings belong to a category of narrative called the hero’s journey.

The hero’s journey is a term coined by American mythologist Joseph Campbell to refer to the monomyth, the one basic narrative pattern that is found in nearly every culture and civilization throughout human history.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell laid out the phases of the hero’s journey. They fall into three parts: departure, initiation, and return. These phases contained most or all of the following components:

Departure:

- The call to adventure (often brought by the “herald”)

- Refusal of the call

- Supernatural aid

- The crossing of the first threshold

- Belly of the whale

Initiation:

- The road of trials (including new allies and enemies)

- The meeting with the goddess (a.k.a., mystical marriage)

- Woman as temptress

- Atonement with the father

- Apotheosis (elevation in rank to godhood)

- The ultimate boon

Return:

- Refusal of the return

- The magic flight

- Rescue from without

- The crossing of the return threshold

- Master of two worlds

- Freedom to live

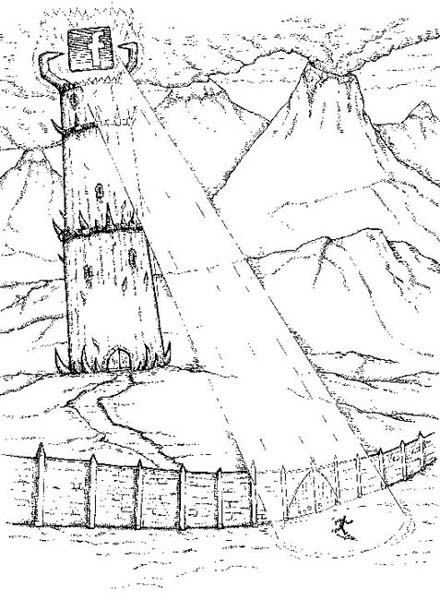

The graphic on the next page depicts the journey, though with some added or altered terms.

Broadly speaking, the hero’s journey is the story of 1) a hero (or heroine) who was safe and protected at home, perhaps spoiled and longing for adventure, who is 2) forced to go out into the scary outside world, where he meets many new challenges and allies but eventually overcomes them all to truly become a mighty warrior, and who then 3) returns home to bring to his people the fruit of what he’s learned and achieved.

The application to The Hobbit is clear. Bilbo was the epitome of the spoiled and protected—and untried—innocent. He is cast out, quite against his will, into that terrifying unknown beyond the boundaries of his land. In this journey, he encounters new allies and enemies, gains a mentor, finds a magical talisman, and achieves heroic, grown-up things of which he never believed himself capable. In the end, he returns to the Shire with the riches won on his journey. But he is no longer the same. He is master of two worlds—those inside and outside the Shire—and prefers the company of elves and wizards to that of his fellow hobbits.

Frodo’s journey in The Lord of the Rings follows the same pattern, though on a more epic scale. Many people wonder about the extended ending of the book version of The Return of the King. In a purely narrative sense, the story is essentially over when Sauron is defeated. All that is required is a return home to enjoy the peace and innocence the heroes have protected.

But from a hero’s journey perspective, the story is not over until the heroes have returned home and brought to their families the wealth of what they have learned and become on their travels. They went out to war and became heroes. When they get home, they find that their heroism is in need once again. They lead the uprising against Sharky and achieve the Scouring of the Shire.

Had they never gone on their journey, no one would have opposed Sharky and his minions, and the Shire would’ve been surely enslaved. Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin would’ve been herded to their doom like all the rest of the hobbits. But they are heroes now, and dark times call for heroes.

Tolkien wrote hero’s journey tales. Certainly he didn’t rely on Joseph Campbell’s work directly, since The Hero with a Thousand Faces wasn’t published until 1949 and The Hobbit was published in 1937. But Campbell’s genius was to recognize the monomyth in every culture and to condense the various components into a cohesive list, like the one found previously. Doubtless Tolkien sensed these steps inherently, as have so many others across every civilization throughout human history. It has even been argued that the hero’s journey is a fingerprint of the divine.

Because, truly, it is man’s story. We all start as children who are sheltered in some respect or another but who must eventually venture out into the frightening world of adulthood. Hopefully, while on this journey, we “grow up,” we become individuated (to use Carl Jung’s term), we finally “get it” and achieve a level of mastery that allows us to excel in our lives as confident adults. Finally, we bring what we have learned and apply it to the home, family, and community in which we choose to live.

Once you understand the phases and their components of the hero’s journey, you’ll begin to see it everywhere. At least half of the stories Hollywood and novelists produce are hero’s journey stories. Examine Star Wars, The Little Mermaid, Cars, Ender’s Game, The Hurt Locker, The King’s Speech, No Country for Old Men, and many, many others, and you’ll see the monomyth lying beneath. Indeed, George Lucas befriended Joseph Campbell and worked with him extensively to make Star Wars the quintessential hero’s journey tale. Tolkien’s narratives are no less hero’s journey stories.

The Hero’s Journey, Hobbits, Fear, and Evil

Psychologist Carl Jung would say that the hero’s journey is the universal coming of age story, the road everyone must take if he or she is to reach fully realized adulthood, a process he called individuation.

If hobbits are the children of Middle-earth, then those sent out into the world—those who survive and return, anyway—are the first hobbit adults. They are sadder but wiser, acquainted with the ways of the world, able to teach and lead and equip a new generation, if anyone will listen.

In the world outside the Shire, there is fear and evil. A child might be protected from such things, but one who would mature must face them. Both Bilbo’s and Frodo’s stories are tales of untried neophytes facing fearful evil and gaining progressively greater levels of competency as a result.

Bilbo’s fears of traveling beyond the borders of the Shire seemed well-founded when he and the dwarves—without Gandalf—encountered the three trolls roasting mutton. He was not far from home and already something wanted to eat him. Would have too, had Gandalf not come along.

Funny how Gandalf disappeared and reappeared at crucial times during Tolkien’s tales. Had he been there all along, the hobbits in his care would never have learned for themselves the lessons of the road to heroism.

Stop for a moment and consider your own story. Can you recall any hard lesson that you learned only because no one was there to protect you or take care of it for you? Maybe a sibling or friend fell into deep water, and no adults were around. Maybe you were the only one to see the fire begin. Maybe the scorpion got in the house while you were alone.

All of us prefer to call on someone bigger, wiser, and stronger to protect us. That’s natural. But sometimes the chain of possibilities ends with you. You are the last link. No one else is there. If the good is going to happen or the bad is going to be avoided, it’s up to you.

Such moments are the birthplace of heroes.

Bilbo’s Inner Journey

If you had to pick one theme that is at the heart of The Hobbit, it would probably have to be Bilbo’s rise to heroism. Other themes have been suggested by analysts—like issues of race, lineage, and character—and certainly those are prominent in the book. But in the end, it is the story of Bilbo’s transformation from spineless to fearless, from spectator to player, and from child to man.

Let’s track his transformation. And perhaps ours, as well.

Plunging Into the Unknown

The first fear Bilbo had to confront was that of leaving his comfortable home and going on some random and obviously ill-fated “adventure.” Why would he ever do such a thing? He wouldn’t! Not if left to his own preferences.

Sometimes what we fear is simply the unknown. If you never leave your home, you can begin to think that other places are dangerous. One is reminded of the movie The Truman Show, in which the title character has been conditioned all his life to believe that life in his little town on his little island is the only source of safety in the world. Consequently, he is terrified to even think of leaving, though the outside calls to him on some level.

A certain woman was pregnant for the first time. At first, she was simply excited about this new life growing within her (when it wasn’t making her sick). But as the months passed and the great deadline began to approach, her fears mounted. What would happen? What would it be like? Could something go wrong? She and her husband began to fill their great lack of knowledge with information: reading books, watching videos, talking to other new mothers, and more.

The idea of a frightening D-Day approaching inexorably is terrifying. But at least in pregnancy you have nine months to prepare for the event. What if in a single day you found out you were pregnant and due to give birth that very day? To have feared labor and delivery your whole life and then to have it happen right away would be even worse.

Such was Bilbo’s situation. He’d always feared the world outside the Shire, and now, with no warning, he was thrust into it. Not with a handpicked band of trusted friends, either, but with strangers completely unlike himself. He might as well have been kidnapped by Vikings.

Even if he longed for an adventure, this wasn’t the one he would have chosen. Not only was he not going of his own will, he was billed as a burglar, something he was most decidedly not. What was Gandalf doing to him? And why had he picked Bilbo, of all hobbits, to visit this curse upon?

Perhaps you have been through something similar. For years you’d feared some scenario, and then one day you were thrust into it, quite against your will. Were you drafted into something you didn’t volunteer for? Did you deal with it more or less like Bilbo did? Kicking and screaming? Reasoning or bargaining? Chances are, you weren’t able to get out of it.

Did anything good come of it? Did you gain anything from the experience, even though you hadn’t chosen it? Some of our most important life lessons come when we’re forced to do something we never would’ve chosen to do on our own.

Problems We Cause Ourselves

Bilbo hadn’t been on the road with the dwarves long before he encountered the three trolls. Now he had something real to fear. Many times, the unknown is worse than what actually transpires. Other times, the thing that actually transpires will try to eat you.

In this case, it is Bilbo’s cheekiness, not his timidity, that gets him into trouble. Had he just gone back to warn the dwarves of the trouble ahead, instead of trying to pinch a troll’s coin purse, much grief would’ve been avoided.

Sometimes we, too, get into trouble we should’ve avoided. Perhaps it’s because, like Bilbo, we’re wanting to show off or prove something to someone. Maybe we’re addicted to the adrenaline rush we get when we take a risk.

In an attempt to escape from the trolls, Bilbo uses his small size to hide, like a child forgotten in a tussle among adults. That’s an unwitting beginning to his eventual practice of using his unheroic attributes to turn him not into a brawling warrior but a canny burglar. But as Bilbo hides, the dwarves get trapped one by one, until it’s just Bilbo and Thorin left.

Bilbo shows his first sign of heroism here, when he attempts to save Thorin by grabbing a troll on the leg. It was a foolish, futile gesture, but it came from a heart that was beginning to care about the others in his group. The fact that he was more or less the cause of them all getting caught probably accelerated his concern, but his little melee was still a step in a good direction.

What about you: Have you ever gotten into a fearful situation that you brought on yourself? Did it result in others getting hurt? Hopefully that’s a lesson you won’t need to repeat.

Cleverness in the Face of Fear

After a restful stay in Rivendell, Bilbo and the dwarves were off again on their quest toward the Lonely Mountain. But it’s not long after that they are set upon by goblins and captured.

The farther from the Shire they travel, the greater the dangers become and the hardier the heroes must be to weather the journey.

So it is in our own lives: adulthood can be wonderful. Striking out on our own, forging our own identity, reinventing ourselves, coming into our own, forming a family the way we feel it should be done. But adulthood can also be a frightening realm. For most people, the transition from child to adult has nothing to do with physical age. There are sixty-year-old babies and eight-year-old elders, in a manner of speaking.

In our lives, as in the hero’s journey—and in Bilbo’s life—the deeper we go into the realm of adulthood, the more heroic we need to be. Pansies need not apply.

It is the school of fears and crises, and even failures, that brings out the hero in all of us.

Gandalf rescues Bilbo and the dwarves from the goblins, but in the battle, Bilbo is separated from the group and knocked unconscious. When he wakes up, he finds himself alone in a dark cave. He feels about on the floor and discovers a ring of some kind, which he drops into his pocket.

And so, the event that changes Middle-earth forever happens as easily as a small metal circle dropped into a wanderer’s pocket. Eventually that ring will be used to destroy the greatest evil that has ever faced that world. Had Bilbo never been pulled from his comfortable living room, who knows what would’ve become of Middle-earth?

How many of your own positive developments and discoveries have come because you were taken to places you never wanted to go? Sometimes the universe has to drag us kicking and screaming to the things we will come to most treasure. It’s almost enough to reaffirm one’s faith that there really is a greater mind at work in the affairs of men and hobbits.

Certainly the Ring wanted to be rid of Gollum, so an evil will was at work. But it could’ve been picked up by a goblin or even some animal to transport it out of the caves. That it was found by a free hobbit whose heart was good was no accident.

It is at this point that Gollum enters our story. The Ring is his precious, but when he encounters Bilbo and wants to eat him, he still has no idea that the Ring has abandoned him.

Whether in fear or courage, or simple desperation, Bilbo draws his sword and brandishes it at Gollum. Again, it is fear that brings about heroism. How true that is, if heroism is there waiting to come out.

Gollum shows his own canniness by shifting from force to shrewdness, challenging Bilbo to a game of riddles—with the death or deliverance of Bilbo at stake.

But it is Bilbo’s cleverness (though some would call it trickery) that gives him the victory. “What have I got in my pocket?” Gollum cannot guess, and so Bilbo has used his brain to prevail where his sword arm would probably not have.

When faced with fear or evil, a direct assault is not always the most prudent response. Often it is the right choice, however, and the failure to act with force when force is called for will lead only to more evil in the future. It takes wisdom to know whether sword or subtlety is called for against any given foe.

Despite Bilbo’s victory, Gollum intends to eat him. He returns to his island to retrieve the Ring, which he will don to sneak up on Bilbo and vanquish him. But he realizes the Ring is lost, and he comes after Bilbo—now a true burglar, in Gollum’s eyes, at least—to wrest it from him. But Bilbo “accidentally” puts the Ring on, turns invisible, and uses that power not only to find the way out of the caves but to escape the goblins guarding the entrance.

Bilbo may have entered these caves—the belly of the beast, in hero’s journey terms—as an untried neophyte, but he emerges as a sly thinker who, in this case, at least, has mastered his fear enough to keep his head and use what advantages come to him in the heat of a crisis.

Consider Luke Skywalker in the bowels of the Death Star. He enters as a spoiled farm boy, but when he comes out on the other side of that trial, he is a hero capable of great deeds.

What crucible have you been through that made you a better person? By definition, a crucible is something painful and even destructive. Life turns up the heat beyond your ability to withstand it—and it transforms you from one state of being into another. It purifies you, allowing the junk to be swept away and the true value to pour out and form into something strong and fine. What crucibles have you been through?

In Bilbo’s case, he not only learned how to use his mind to deal with fearful situations, he also found the key to, well, pretty much everything. Crucibles have been known to do that.

What beneficial lessons—or magical talismans, so to speak—have you learned, through duress, that you would never have found had you not been forced to endure it?

The next time you find yourself in a crisis, look not only for the smart way to handle it but also for the powerful key that might be sitting on the ground right beside you.

Heeding Warnings

Bilbo is reunited with Gandalf and the dwarves but is soon threatened again, this time by wargs who summon the goblins. The intrepid group is rescued by giant eagles who bear them to safety.

Sometimes our enemies team up against us, and sometimes help comes from unexpected places.

Gandalf leaves the group again (one might begin to suspect that some big trial is ahead of them…) but leaves them in the care of Beorn, a man-bear creature, who sends them on a secret path toward their destination. He warns them that the journey is dangerous and they must not depart from the path. But we know what they will do. They soon become separated in the dark forest of Mirkwood, and Bilbo wakes up and finds his legs bound with sticky filaments and a giant spider advancing on him.

The more perilous the task, the more careful one must be to attend to procedure. Anyone can start a fire in a forest, but it takes great care and training to maintain a helpful fire that clears away the underbrush but doesn’t become an inferno. Anyone could attempt to rescue someone caught in raging floodwaters, but it takes extreme care to emerge from that struggle with a positive result. Having said that, the rewards of successfully navigating a tricky bit of water can be tremendous.

Had the dwarves and Bilbo followed directions precisely, had they simply stayed on the path, they would’ve come out from their forest journey unharmed and much nearer their destination. Instead, they ignored what they’d been told, and they nearly paid the ultimate price.

Has it been that way for you? Have you ever felt that the warnings you’d been given were too alarmist or legalistic, and should be discarded? Have you ever rejected someone’s advice but ended up wishing you’d listened?

Some lessons can’t be learned unless you go against what someone has told you to do. Has any child ever really believed his parent’s warning that the stove top was very hot? Probably not many. And even though a child might believe that stuffing yourself with candy or cake will make you sick, she still has to try it at least once.

Not that this will prevent you from warning others not to touch the stove top or stuff themselves with sweets. We should warn them, even if we know they probably won’t listen.

Naming Your Weapon

Back to Bilbo, who with bound legs is facing a monstrous spider. It’s the stuff of nightmares.

But this is not the same Bilbo who left the Shire, even if he doesn’t realize he has changed. This is a hobbit who has faced so many dire threats in such a short time that he’s almost beginning to consider such things his normal way of being. So he whips out his short sword, cuts himself free, and slays the giant spider.

He can’t quite believe it, and he even passes out for a bit. But when he awakens:

The spider lay dead beside him, and his sword-blade was stained black. Somehow the killing of the giant spider, all alone by himself in the dark without the help of the wizard or the dwarves or of anyone else, made a great difference to Mr. Baggins. He felt a different person, and much fiercer and bolder in spite of an empty stomach, as he wiped his sword on the grass and put it back into its sheath. “I will give you a name,” he said to it, “and I shall call you Sting.” (The Hobbit, chapter 8)

This is the key moment in Bilbo’s inner journey. Everything that came before was preparation for this instant, and everything that came after is the testing and using of this change, now that it has occurred.

Here Bilbo has become a man—or an adult hobbit, if you prefer. All alone, by himself, in the dark, and without the help of a powerful wizard or a band of hardy dwarves, Bilbo has slain a monster. Being small couldn’t get him out of danger, nor would any riddle or trick deliver him. It came down to the strength of his arm and the edge of his sword.

And he was victorious.

Defining moments come according to a schedule we know nothing about. Perhaps it is a house suddenly afire or a revolution we become caught up in or a decision made by someone else that puts us in the front row of the decision of our lives. It doesn’t matter how or when it comes. What matters is what we do when it’s upon us.

We are all on an inner journey. We are all forced out of our Shires and cast into the belly of the beast. We all face fears and evils beyond our reckoning or power to escape. We all encounter enemies, and we all have to go through crucibles and learn things the hard way. Most crucially, we all come to our moment of truth, when everything else falls away, and it is only our choice that matters, and heaven and earth stand by to see what we will choose.

Have you had your moment yet? Chances are, you’ve at least had several smaller ones—little moments of truth that have each led to the next one. Eventually a moment will come that will forever shape your personality, either because you responded well in that moment and you like what you have become, or because you responded poorly and you vow to spend the rest of your life making up for it.

If you are past that moment, think back on it. Stop to ponder it before moving on.

The ancient biblical patriarchs used to erect piles of stones to mark where something significant happened. They wanted to always remember what had happened—and they wanted their children to ask what those piles of rocks were, so there would be opportunities to rehearse the story again.

Bilbo marked this event by giving his sword a name: Sting. Now it was no longer a knife, and he was no longer just a woebegotten hobbit. Now the sword was a powerful talisman, and he was a warrior to be reckoned with.

With the naming of Sting, Bilbo passed from the realm of childhood to the realm of adulthood. He was no longer a passive victim to whom terrible things happened. Now he was a doer of great deeds. The difference cannot be overemphasized.

Which are you?

While this moment marks the end of Bilbo’s transformation, it is not the end of his hero’s journey. The purpose of the journey is to create a hero—not for the mere sake of it, but in order that this individual can confront the great evil that is threatening the land.

From this point on in The Hobbit, Bilbo is a doer of heroic deeds. With his sword and his ring and his brain, he rescues the dwarves from the spiders, and then from the Wood-elves, and then from the dragon itself, and finally from the Battle of Five Armies. Had the dwarves not been given their reluctant burglar from Bag End, they would’ve perished ten times over and never reached, much less won, the object of their quest.

Are you a doer of great deeds? Are those in your care protected because you are in their lives? Slay your monster, name your sword, and take your place among the heroes.

Conclusion

Bilbo faced great fear and evil, and he emerged a hero. We could trace Frodo’s journey just as well, for it follows the same path from childlike victim to responsible champion.

What have been the steps of your hero’s journey? Where are you on that map? What might you do to advance to the next phase?

Should you take it, the journey will change you forever. You will never again be the innocent you once were. The fears faced and the responsibilities accepted transform you.

It is said that the person who returns home after going on his hero’s journey will never need to go on it again. Instead he becomes the mentor, the wise wizard to a new generation of those just beginning the journey. If you have been on this journey—there and back again—who around you might benefit from what you have learned?

When Gandalf chose Bilbo to be the burglar for the dwarves, he said this to ease their misgivings: “There is a lot more in him than you guess, and a deal more than he has any idea of himself.”

So it is with you.