Three Campaigns

THERE IS AN old saying that troubles come in threes. In the years following Clay’s disappointment at the Harrisburg convention, he would be a living illustration of it. During that time, he waged three campaigns, all interconnected but each having different objectives. One was the immediate effort to get Harrison elected. Concurrent with that effort was Clay’s own bid to follow Harrison in the presidency in 1844. He planned to begin staking his claim for Whig loyalty with selfless and energetic exertions for the party and Old Tip. He counted on Harrison’s pledge that he would serve only one term and looked beyond the old man to other possible rivals.1

The third campaign was economic, and involved reviving the national bank to stabilize the currency, sustaining a protective tariff to promote industry, and distributing land revenues to the states that in turn would be used to fund internal improvements. Clay was reasonably confident that the realization of the Whig program would be relatively easy. He was certain that he could persuade Whig majorities in Congress to pass it, and that he could rely on Harrison’s assurance of executive passivity to sign it into law.

The third campaign, though, proved the adage about troubles coming in threes. A development that shocked the country was the cause, although Clay himself had both dreaded and expected its occurrence. No foresight or preemptive action could have prevented what happened—the devastation of the Whig program and the near destruction of the party—and nothing but Clay’s abject surrender to circumstance would have prevented many from settling on him almost all the blame for what happened. Yet the die setting up the debacle had been cast by other hands in another place long before. It had been cast at Harrisburg by men who had wanted to win the election at all costs. When it all went wrong, it was easier to blame Clay.

CLAY AND HIS slave Charles Dupuy moved into Mrs. Denny’s boardinghouse on Third Street for the first session of the Twenty-sixth Congress, but later moved to rooms at Mrs. Arguelles’s.2 Even with the glowing accolades of the Brown’s Hotel banquet still in his ears, Clay was uncharacteristically melancholy that winter. He had a nagging cold, and the weather was bitter as an occluded front dropped enormous amounts of snow on the capital. John had traveled to Missouri and wound up “entirely dissatisfied with it,” as Clay had expected, but now as John headed back to Ashland “in the dead of winter,” Clay was uneasy until he knew that the boy had reached home. “This is the last winter that I shall be separated from you, whilst we both live,” he promised Lucretia, and likely he meant it, at the time.3

In Washington, drafty rooms resisted the efforts of even the most cheerful fires to warm them, and going anywhere outdoors became an exasperating ordeal. Such winters made “small folks still smaller,” said one Virginian. “It chills the blood and makes us irritable which makes us disagreeable to others as well as ourselves.” Little wonder then that Clay’s work in the Senate was marked by increasing irritability. The House of Representatives reminded Clay’s grandson Martin Duralde “of a parcel of schoolboys,” but Clay had grown weary of many colleagues in the upper chamber as well, often finding them dim or venal, sometimes both. The discovery that members were abusing their mileage allowance calculations and engaging in small corruptions with the franking privilege and with printing, fuel, and stationery allowances appalled Clay. He promoted efforts to clean this up by limiting benefits such as the stationery allowance to $20.4

But it was the larger and recurring issues that summoned his fiercest responses. In mid-January, Democrats led by New Yorker Silas Wright, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, brought up the Subtreasury bill for debate yet again. Clay was on fairly civil terms with Wright, but he regarded these dogs with their Subtreasury bone increasingly tedious, and he now so vehemently clashed with the finance chair that it briefly brought the Senate to a standstill. Wright was overmatched. “His voice is not melodious,” admitted a friendly description, “though after listening to it a short time it becomes not unpleasing.” It was hardly a qualification for going into verbal battle with Henry Clay. He also squabbled with Mississippi senator Robert Walker—“little Walker,” in Clay’s estimation—whom he reported to Lucretia that he had “scornfully repelled. My friends said that I annihilated him.”5

Calhoun was also involved in this debate, though, and that spelled trouble. Calhoun had hoped that Clay or Webster would carp about Harrison’s nomination in order to divide the Whigs and leave an opening for him to run, but Whig unity had forced the South Carolinian to continue his rapprochement with Van Buren. He attended the president’s New Year’s Day reception at the White House, where the two whispered plans for a private meeting. The result was the revival of the president’s darling, the Subtreasury, this time with Calhoun’s influential support. Clay wearily went unto the breach. He voiced the same objections and advanced the same arguments he had spoken in the seemingly countless previous debates on this question, but Van Buren was obviously determined to have this victory, Pyrrhic though it might be. As the bill assumed the shape of an idée fixe, at least for the Democrats supporting it, Clay angrily deduced that he was fighting a determination to continue voting on this measure until Congress got it right, at least by the administration’s lights. Calhoun’s trimming and turning especially annoyed him, and the Democrat press complained that Clay repeatedly singled out the South Carolinian as “the special object of his wrath this winter.”6

Clay lost his temper as he hoarsely ran through the now familiar litany of Jacksonian transgressions, including the Spoils System that corrupted the public service and the excessive executive authority that threatened to make the president a despot. Van Buren had perpetuated these ills, Clay growled, and his cronies had sullied government while wrecking the economy. There was, he shouted, “a day of reckoning at hand.”7

On January 23, 1840, Van Buren finally saw his Subtreasury plan pass the Senate with a slim six-vote majority, thanks to his alliance with Calhoun. The work to secure passage in the House would be more difficult and consume six additional months of debate and maneuver, but this latest fight only made Clay more determined to put aside his distaste for campaigning and help elect Harrison. He exhorted Whigs to “tell your constituents of the nomination—of a bleeding Constitution—of the Executive power against which we are waging a war of extermination—of executive machinery and executive favor—of one President nominating his successor and that successor his successor. Tell them to put forth all the energies they possess to relieve the land from the curse which rests upon it.”8

In February, as Clay prepared for a campaign trip to Richmond, he wrote to Henry Jr., who had taken his father’s loss of the Harrisburg nomination particularly hard. Henry Jr. looked at the whole world somberly, an inescapable consequence of his temperament, but Clay was happy that Julia Prather, pretty, clever, and lighthearted, had found his son. She tempered his brown studies and was in the process of filling his life with little Clays, though that too was cause for concern because childbearing had not been easy for her, with two daughters, Matilda and Martha, dying in infancy. They were expecting a new arrival any day, though, and Clay was eager for news. Soon he learned that Thomas Julian Clay (always “Tommy” to the family) had come into the world.9

Days later, however, another letter arrived from Henry with the terrible news that Julia was dead. Complications from Tommy’s birth were the cause. Clay spent a sleepless night before writing to his son the next morning—the news “was so sudden and appalling,” he said—and the distraught tone of Henry Jr.’s letter that revealed a man quite overwhelmed by grief worried him. Clay gently reminded his son that Julia had left him “tender & responsible duties to perform towards the children of your mutual love and affection.” Clay could not help but remember in vivid detail the wretchedness of that cruel December five years earlier when Anne had died, and in the same way as Julia, her fate also marking a time both of birth and of death. “I beg therefore, on my account, as well as that of my dear Grand children,” Clay said to his shattered boy, “you will take care of yourself.”10

CLAY’S HEART WAS out of the Richmond trip, but so many extensive arrangements had been made that he decided to go.11 He left for Richmond with Henry A. Wise, who was ailing with a severe sore throat that made speaking difficult. A large crowd awaited their arrival at the city’s railroad depot and escorted them to the Powhattan House, where Benjamin Watkins Leigh introduced him to a gathered throng. People had come from all over the state for the Whig rally, some even braving horrid roads. William Bolling, a friend from Clay’s youth, was among them. Clay was consoled by these companions, and Bolling found his old friend at Leigh’s residence for tea. Frank Brooke was there too, and the group talked well into the night before returning to the Powhattan. In many ways it was just what Clay needed, and he was soon glad that he had made the trip.12 The next day, a grand dinner was held in honor of their famous guest, an event touted as “the greatest ever given in Richmond, or perhaps in the United States” and so largely attended that it had to be held in an enormous warehouse. William Bolling came in through the door set aside for invited guests and thus managed to sit near Clay and hear “the greatest Orator, & the greatest man & patriot now living in these United States.”13

Clay used this speech to enlarge the revision of his early history for current political circumstances, consciously adding to the creation of the boy who never was, an image of “a lank, lean youth of twenty, with sandy hair and ruddy complexion, fatherless, homeless, friendless, and penniless” who had left Richmond those many years ago “to seek his fortune in the ‘far West.’”14 The audience was both captured by the fiction and captivated by his telling of it, including those whose personal recollections of young Clay, even if dim, were most certainly and decidedly different from this new account. It did not matter. The huge gathering was pin-drop silent, which made the frequent eruptions of thunderous applause echoing through the warehouse all the more deafening.15

John Tyler was there, arriving after everyone had already begun eating, but he was immediately introduced by Benjamin Watkins Leigh and spoke very briefly, insisting that he had merely come to honor Clay, whom he lavishly praised. Interestingly, though, “he avoided political allusions as improper in consideration of his position at this time.”16

The journey coming so close to the news of Julia’s death put Clay in a reflective frame of mind, and his swing through Hanover County on the way back to Washington only increased his pensiveness. The stop at the Slashes was bittersweet. He had not been there for almost fifty years, and he found everything so changed as to be unrecognizable. His maternal grandparents’ and his father’s graves were not only without markers but also under a wheat field. A row of cherry trees partly remained, but he noted that like him, they were aged and frail. The hickory tree that had produced “the finest fruit of that kind which I ever tasted” was down and rotting. The house once called Clay’s Spring still stood but had been considerably altered, though Clay identified the room where he had been born. He met only one person he remembered from the old days, an elderly woman of eighty, a cousin of his mother’s and “evidently not long for this world.” He visited the church where he had first attended school, but it too “was in a decayed condition which indicated that we should probably both tumble down about the same time.”17 Lucretia must have read his account of visiting the Slashes with a sense of wistfulness as well, hearing about a time before he had known her and detecting an uncharacteristic sadness in his words. In the wisdom of the times, a man’s sixty-third year was the pivotal age that ordained great changes in health, the beginning of physical devolution. Clay soon noted that his birthday would mark his grand climacteric, and he said plainly to Lucretia, “I should be glad to be spared a few years longer until I see the Country through its difficulties, and get over my own.”18

Observers judged the trip a success in what it meant not only for Whig unity and Harrison’s candidacy, but for Clay’s reputation. “There is usually much hollowness in such things,” remarked James Barbour, but “the pageant of Mr. Clay’s reception” pointed to the fact that “justice awaits the real patriot.” The sentiment and his obvious popularity were not lost on Clay’s friends, or even those who at present found it prudent to be his friends. Even before the Harrisburg convention, Harrison and Scott supporters had whispered assurances that either of their presidencies would be directed by Henry Clay. It was a deliberately flattering concession at the time. Later, though, for Harrison’s supporters as well as Harrison himself, not to mention his running mate, it prepared the ground for a toxic suspicion that others would nurture.19

HENRY JR. ARRIVED in Washington soon after his father’s return from Virginia. Clay judged him “in pretty good health, but still in very bad spirits.”20 He likely counseled Henry to follow his favored form of therapy in coping with grief, which was to travel and above all stay busy, for Henry did both in the months to come. By summer he was back in Kentucky and deeply involved in promoting Harrison’s candidacy. He also announced himself the Whig candidate for lieutenant governor. Disappointed in that bid, he challenged Thomas F. Marshall for the Lexington district’s congressional seat, though he ultimately withdrew in the interest of Whig unity.21 He would never really recover from losing Julia, and there would never be the suggestion of his marrying again, an odd path for a young widower with children. Clay at first worried that the children would add to Lucretia’s already heavy responsibilities, a burden (Lucretia would have bristled at the word) in addition to that imposed by the Erwin and Duralde broods, often in residence at Ashland. But Henry III, Nannie, and Tommy were largely raised by Henry Jr.’s first cousin, Nanette Price Smith, Lucretia’s niece. It was plain that their father would never love anyone else, and he evidently would not marry without love. He became a living monument to Julia’s memory and continued as such even after he found something he believed worth doing with his life, even if his father did not approve of it.22

On May 4, Clay participated in a grand procession of the Young Whig Men at Baltimore to ratify the Harrisburg ticket. At the Canton Race Track, he addressed a teeming crowd, and if there had been any lingering doubts about his purpose in the coming contest, he allayed them to the cheers of his audience. “This is no time to argue,” he shouted. “The time for discussion is passed …. We are all Whigs—we are all Harrison men. We are united. We must triumph.”23

It was a rousing performance, but it also disclosed an ominous discovery. He found that addressing large groups in the open air worked “a tremendous exertion of the lungs,” and the parade and speech left him exhausted and slow to rebound. This was a new and sobering infirmity for a man who had earned his fame as well as his political fortune with a compelling baritone that could be musical in small settings and, up until now, reliably stentorian outdoors. Because he did not feel up to it, he declined to attend “an old fashioned Virginia Barbecue” even though its sponsors offered to schedule it for his convenience.

In addition, the affair at Baltimore had been raucous, celebratory, and for Clay probably the first full-blown example of the ballyhoo that defined the 1840 campaign. He seems to have found it distasteful. He turned down an invitation to attend a Fourth of July celebration planned by Whigs in Philadelphia. “I think self-respect requires,” he said after Baltimore, “that I should not convert myself into an itinerant Lecturer or Stump orator to advance the cause of a successful competitor.”24

Despite this resolve, Clay accepted an invitation to a public dinner for him in Hanover County in late June. The event provided him with the irresistible opportunity to return again to the Slashes as a proud native, but it also gave him a forum to declare Whig principles and outline a Whig program. That this should be done more forcefully had become a special concern for him. In late May he expressed regret that the Harrisburg convention had issued no platform, an omission that allowed Democrats to say that the Whigs had no program and to disparage Harrison as “General Mum.” Although he was aware that many of his fellow party members thought it better to say nothing and avoid the possibility of words being twisted, he disagreed. He wanted someone to put out a statement explaining what a Whig administration would accomplish.

While Clay was stating the Whig case, the House of Representatives finally passed the Subtreasury bill on June 30 by a vote of 124 to 107, the result of the unyielding efforts of Calhoun’s lieutenants and administration operatives. Van Buren delayed signing it into law until July 4. It was a symbolic gesture that Andrew Jackson believed would improve the Little Magician’s reelection chances just as Jackson’s Bank veto in 1832 had boosted his. Yet Van Buren was not Jackson, and the Subtreasury had become as divisive for Democrats as it was distasteful for Whigs. The nearly four-year fight to put it in place had damaged the party in New York and Virginia, and in retrospect quite needlessly, because Treasury secretary Levi Woodbury had been shifting money from state banks to the Treasury for three years under the terms of the Deposit-Distribution Act, in essence a de facto subtreasury. By the time Van Buren received the bill, the economy was again in shambles, finally showing the ill effects of the renewed economic slump, and many voters were ready for the change that the Whig economic program promised.25

“FOR SEVERAL MONTHS I have been afflicted with constant colds and hoarseness,” Clay wrote Lucretia shortly after returning from his two-day stay in Hanover County. He described a troubling routine for July: “Two or three times I have put on and taken off my flannels. I have begun again to rub the surface of my body every morning with Spirits and Salt.” Under instructions from his Washington physician, William Thomas, Clay became a steady customer of apothecaries C. H. James and R. S. Patterson. He told Lucretia, “I must find some relief, or I cannot survive.” That was unlike Clay, and it was also unlike him to leave Congress early for home. Not only sick but exhausted, he departed Washington on Sunday, July 12, eight days before the first session adjourned. The rivers were navigable, allowing him to take the Wheeling route, and he was at Ashland in a little over a week.26

He was determined to get some rest and catch up with the family, whom he had not seen for more than eight months. He received four to five invitations a day to speak at rallies and meetings, but he turned them all down.27 Yet his resolve to rest wavered when he was given the chance to speak at a large Whig convention to be held at Nashville in mid-August. In part, bearding Old Hickory in his own den was more than appealing, especially since Jackson had been misbehaving, to Clay’s way of thinking. Jackson had published a letter in the Nashville Union endorsing Van Buren and lashing out at Harrison’s record as an officer and statesman, a violation of the tradition that former presidents should not act as political partisans.

The convention soon became “one of the most immense gatherings ever convened in the South-western States.” At least thirty thousand enthusiastic Whigs showed up, took over the city, and hurrahed for Harrison and Tyler as they went to dinners so massively attended that at one there was room for only one thousand of the ladies present to sit down while they ate.28 On August 17, Clay made the principal speech to the gathering. He had been worried about his voice, but it did not fail him, and the cheering, stamping throng frequently stood rapt as he defended his actions resolving the 1825 election, assailed Van Buren, and praised Harrison and Tyler. That much was expected, but some unpredicted portions of the speech particularly elated the audience. One of Clay’s remarks seemed spontaneously witty. When he brought up Felix Grundy, someone called out that Grundy was in East Tennessee campaigning for Van Buren. Clay immediately retorted, “Ah! … at his old occupation, defending criminals!”29 The witticism had actually occurred to Clay shortly after arriving in Nashville. He had asked if Grundy was in town, and when told about the state speaking tour, the retort about “defending criminals” occurred to him a full two days before the convention speech. Like any seasoned performer, Clay had it handy for a seemingly off-the-cuff reference.30

He was also ready for an apparently spontaneous jab at Van Buren in comparison to Harrison. Responding to Democrat scoffing over Old Tip’s scant military achievements, Clay shouted that Harrison had fought more battles without suffering a defeat than any other American general. Democrats claimed Harrison was not a statesman? Clay countered that Harrison had held numerous posts of public trust. Then someone in the crowd shouted for Clay to tell of Van Buren’s “battles.” Clay flashed his wide smile, and the crowd tittered. “Ah,” he said. “I will have to use my colleague’s language, and tell you of Mr. Van Buren’s three great battles! He says that he fought general commerce, and conquered him; that he fought general currency, and conquered him; and that with his Cuba allies, he fought the Seminoles, and got conquered!”31 The multitude roared.

Clay naturally mentioned Andrew Jackson in the speech, and it was these remarks that later caused the most fireworks. Although Clay’s initial reference was gracious—he told the crowd that he had “no unkind feelings” for “the industrious captain in this neighborhood”—he also criticized Jackson for reneging on a host of promises and for appointing Edward Livingston secretary of state at a time when Livingston’s financial embarrassments were as obvious as they were significant. Jackson was already livid over Clay’s visit, but the disparagement of his administration was more than he could stand. Just two days after Clay’s speech, Jackson published a letter spitting with fury in the Nashville Union denouncing Clay for criticizing Livingston after Clay had accepted the State Department in a crooked bargain. “Under such circumstances,” Jackson ranted, “how contemptible does this demagogue appear, when he descends from his high place in the Senate and roams over the country, retailing slanders against the living and the dead.”32

Clay responded the very next day with a lengthy reprise of the events he had described in his speech and concluding: “With regard to the insinuations, and gross epithets contained in Genl. Jackson’s note, alike impotent, malevolent, and derogatory from the dignity of a man who has filled the highest office in the Universe, respect for the public and for myself allow me only to say that, like other similar missiles, they have fallen harmless at my feet, exciting no other sensation than that of scorn and contempt.”33 This, of course, was not true, for Clay was every bit as angry as Jackson. He had traveled to Old Hickory’s backyard and had roused a teeming crowd, but he had also prodded an aging lion who never slumbered and who, once resolved to hatred, never relented. Clay’s peculiar aptitude for making powerful and relentless enemies did not diminish as he aged. At Nashville in the summer of 1840, he reminded the most powerful and most relentless of all his enemies why he was and always would be one.34

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON won the election of 1840 by less than 120,000 popular votes out of some 2.3 million (1,274,624 to 1,127,781), but he stacked up a crushing victory of 234 to 60 in the Electoral College. The election also overturned Congress to install Whig majorities in both houses. These victories resulted from hard economic times, as many across the country resolved to throw out those perceived as having caused the financial mess and refusing to do anything to correct it. Silas Wright groused that considering the kind of campaign that had been waged, the only mandate was to raze the Capitol and replace it with a log cabin, but his wry observation actually reflected deep frustration among Democrats.35

They were in fact more than a little puzzled. Democrats could grumble all they wanted that they had merely been outshouted, but Whigs throughout the country had made plain their plans, and the people gave evidence with their votes of their intention to embrace those plans. Clay clearly outlined Whig intentions in widely reported speeches at Taylorsville, Nashville, and Shelbyville, and others did the same in pamphlets and newspaper editorials. Understanding that the American people understood what the election was supposed to accomplish is key to comprehending what happened in its wake.

The man the Whigs had chosen to run instead of Henry Clay was a pleasant person who basked in good company and was rewarded for his even temper with affection from his family and loyalty from his friends. Yet Harrison’s imposing bearing and unruffled demeanor could not disguise the fact that up until his winning the presidency, his career had been undistinguished. Worse, he had occasionally displayed an unseemly ambition, seeking and sometimes seeming to grovel for public appointments and comfortable sinecures. His talents were modest, and by the time he became president, his health was fragile.36 Discerning Whigs more than suspected his limitations. “Harrison was not the man I most desired to see fill the Presidential chair, but Clay or Webster,” wrote one. “My motto is in my president and in my preacher an aristocracy of mind with commanding intellectual acquirements.”37 Others were less charitable. Andrew Jackson predictably railed that Harrison had played “the part of the Ohio Black Smith [sic]” and found his behavior as president-elect so “disgraceful” as to confirm that Harrison had no “common sense.” States’ rights men such as Beverley Tucker took comfort that Harrison’s shortcomings would weaken the presidency. “The throne is too high,” Tucker said shortly after the Harrisburg nomination, “and it may be well to place a man upon it who will degrade it by his embicility [sic].”38

Clay disagreed to the extent that he knew Harrison was not contemptibly stupid. He thoughtfully evaluated the president-elect, judging his strengths as “honesty, patriotism, a good education, some experience in public affairs, and a lively sensibility to the good opinion of the virtuous and intelligent.” Yet Harrison, thought Clay, was also prone to “vanity & egotism. And the problem to be solved is whether the former can afford protection against the sinister influences to which the latter expose him.”39 Even before the election, Clay had troubling signs that Harrison’s pride might complicate matters. “I should be much gratified to see you on your way home,” Harrison had written to Clay in June, “but the meeting must appear to be accidental. Can you arrange such a one?”40

They had not met then, nor did they meet during the campaign season, accidentally or otherwise. Then after his victory, Harrison traveled to Kentucky to meet with Charles A. Wickliffe, ostensibly on business about his purchasing Harrison’s Kentucky land claims. At first, Harrison said he wanted to meet with Clay as well, but he abruptly changed his mind because it “might give rise to speculation & even jealousies which it might be well to avoid.” Harrison suggested that instead he could meet with an intermediary who could relay Clay’s views and suggestions about the impending administration.41

Harrison’s trip was clearly more related to politics than land parcels, and for that reason alone he should not have made it. Twenty years later, when Abraham Lincoln was elected president, Thurlow Weed suggested that Lincoln travel to New York to visit William Seward, who had been his chief rival for the nomination. Weed cited Harrison’s November 1840 visit to Kentucky as precedent, but Lincoln ignored the suggestion, “wisely” in the judgment of one historian.42

In Harrison’s case, the visit was a bad miscue for several reasons. It revealed his sensitivity over continuing reports that Clay would be the “Mayor of the Palace” in the new administration, directing all activities from patronage appointments to legislative initiatives. In reacting this way, Harrison was playing into the hands of mischief-making opponents, for these predictions either appeared in Democrat newspapers, or they were the work of resentful Whigs jockeying for position by fouling the well for Clay.43

Trying to prove he was his own man and would be the master of his administration, Harrison unnecessarily placed himself amid the divisive quarrels of Kentucky’s Whigs. Sixty-two-year-old Charles Wickliffe was a Whig, but he had always chafed under the ascendancy of Henry Clay, who was his superior in debate. A Wickliffe kinsman candidly likened Charles’s weak oratory to trying to explode “a powder magazine … by throwing snow-balls at it.”44 Well-spoken or not, Wickliffe disagreed with Clay about almost everything. As a member of the Kentucky congressional delegation in 1825, he had voted for Andrew Jackson, and in the intervening years he had staunchly opposed Clay on issues ranging from gradual emancipation to revenue distribution. With his older brother Robert, who happened to be a Jacksonian Democrat, Wickliffe was poised to mount a serious challenge to Clay’s dominance of Kentucky politics. Their mother had been a Hardin, tying them to influential Ben Hardin, another Bluegrass foe of Clay’s, who had given Robert the nickname “Duke,” now “the Old Duke” as he neared sixty-six, because he was the wealthiest and most imperious man in Kentucky. The Wickliffes had a long reach in matters political, social, and even matrimonial: Robert Wickliffe’s youngest daughter, Margaret, was to marry William Preston, a Whig and a friend of Clay’s, just days after Harrison’s visit.45

Harrison’s plan to meet with a member of this family greatly troubled Clay, for it likely meant a Wickliffe association with the new administration that would damage his standing not only in Kentucky but in Washington as well. Moreover, throwing this meeting in Clay’s face just days after the election was both impolitic and churlish on Harrison’s part because Clay was the acknowledged leader of the party in Congress and had worked hard for Old Tip’s victory. In short, it was a costly and ill-conceived way for Harrison to show his independence.

Clay did not stand on ceremony when Harrison arrived in Frankfort on November 21. Instead, he rushed there to head off the Wickliffes. They intended to have Harrison install Robert Wickliffe, Jr., as his private secretary, giving the family the president’s ear, and Charles A. Wickliffe as postmaster general, giving the clan access to vast patronage power. Clay thus swallowed his pride because his political self-preservation required it. He graciously invited Harrison to Ashland. Old Tip accepted, though reluctantly, making it seem he had been dragooned into Lexington.

Clay had him alone, though, and was free with advice. In several conversations, including one on November 25 during Ashland’s midafternoon dinner, Clay discussed cabinet appointments. Harrison offered Clay the State Department, but he turned it down. Peter Porter advised him not only to avoid serving in the cabinet but also to seek a diplomatic post, possibly as minister to England, to be “detached from the political squabbles of the next four years,” but Clay had no intention of detaching himself from the exciting prospects that a Whig president with Whig congressional majorities promised. Taking Harrison at his word about believing in legislative supremacy, Clay looked forward to returning to Congress for the first time in years.46

Sensibly weighing the reality that Webster could not be overlooked by a Whig president, he said that Webster’s appointment to a suitable post would not vex him. He suggested the State Department. In fact, anything but Treasury, because he claimed to believe Webster had no talent for finance. Although Clay was precisely correct about his impecunious rival, his primary concern was the large patronage pool Webster would have at Treasury. He also made an effort to solidify his influence in the cabinet by putting forward the names of friends, especially Crittenden for attorney general.47

Clay viewed these conversations as successful in that they preserved his influence and promoted a positive relationship with the executive branch. For his part, Harrison in the aftermath appeared warmly inclined to Clay. Just before his inauguration, Harrison spoke publicly of Clay as “my firm personal and political friend” and went on to say, “I consider his judgment superior to that of any man living, for … I have never differed with him on any important subject that I did not afterwards become convinced that he was right and I was wrong.”48

By the 1840s, Ashland had become a prosperous farm as well as a showplace. It was also Clay’s refuge from the world. In the engraving above, he is seated in the foreground. The engraving below depicts the pleasant landscape that greeted the many visitors who traveled to the estate as if to a shrine. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky; Library of Congress)

Clay was an expert horseman who began riding as a youth in the Slashes. Through the years, he owned outright, or as a member of syndicates, champion racehorses. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

Foremost among the many artifacts that Clay prized at Ashland was a cracked goblet that George Washington used during the American Revolution. It is still displayed at the estate. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

The artist George P. A. Healy (Library of Congress)

Clay circa 1842. The renowned artist George P. A. Healy was commissioned by Louis-Philippe of France to paint portraits of American statesmen from life. Healy visited Ashland in 1845 and produced several studies as well as the a full portrait to the right. The engraving above suggests that some of Clay’s family were partly correct that Healy had failed to capture Clay accurately. Yet among the many likenesses of her husband, Lucretia thought Healy’s was the best. (Library of Congress)

Copy of Healy’s Henry Clay by Maurie W. Clark (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

Lucretia Hart Clay was an intensely private woman married to an intensely public man, but she was far from a timid recluse. There are not many portraits of her, and this one by Oliver Frazier likely took some license to soften her features. (Courtesy of Dr. Bill Kenner)

Raised within sight of Ashland, Mary Mentelle was a childhood playmate of the Clay children. Her marriage to Thomas Hart Clay brought her formally into a family that already adored her. (Courtesy of Dr. Bill Kenner)

Henry and Lucretia’s second son, Thomas Hart Clay, caused his parents many anxious moments. Expelled from West Point after one term and prone to drunken binges, Thomas finally found his way through the love of a good woman, neighbor Mary Mentelle. (Courtesy of Dr. Bill Kenner)

Henry and Lucretia’s third son was his father’s namesake, Henry Clay, Jr., and became the young man for whom Clay had the highest hopes. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

The death of Henry Clay, Jr., in combat during the Mexican War broke his parents’ hearts and contributed to Henry Clay’s religious conversion. (Library of Congress)

Julia Prather’s marriage to Henry Clay, Jr., brought great joy into the life of an overly serious young man. Her tragic death in 1840 devastated the family and sank young Henry into perpetual mourning from which he never recovered. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

Henry and Lucretia’s tenth child, James Brown Clay, tried several careers before settling on the law and practicing briefly with his father. Clay obtained a diplomatic appointment for James in 1849, and he served one term in Congress in the late 1850s. He sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War. (Courtesy of Ned Boyajian)

James B. Clay’s marriage to Susan Jacob brought another beloved daughter-in-law into the Clay family. Susan greatly admired her father-in-law and took it upon herself to preserve many of his papers after his death. (Courtesy of Ned Boyajian)

John Morrison Clay was the youngest of Clay’s eleven children. He struggled with alcohol in his youth and later displayed signs of the mental disorder that afflicted his oldest brother, Theodore Wythe Clay. His life was transformed by the discovery of his talent for breeding champion racehorses. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

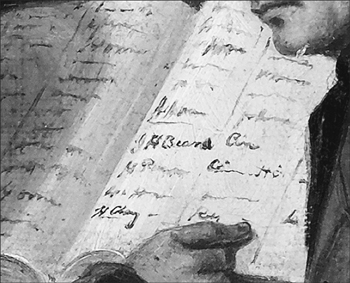

The Illustrious Guest by James Henry Beard

Despite his lengthy retirement from office and his failed presidential bids, Clay remained one of the country’s most popular and recognizable people, as this previously unpublished painting shows. In 1847, New York artist James Henry Beard captured the essence of that celebrity in The Illustrious Guest, in which Clay nonchalantly reads a newspaper while locals gather to stare at their famous visitor. Beard had a sense of humor to match that of his subject, as the detail of the tavern’s guest register shows. The artist has placed his name on it along with Clay’s signature. (Private collection)

The Capitol as it appeared during the Mexican War and the debates over what would become the Compromise of 1850. (Library of Congress)

Henry and Lucretia Clay posed stiffly to commemorate their fiftieth wedding anniversary, both clearly showing the emotional scars of the many family tragedies that plagued their five decades together. Clay was also struggling with a serious cough that he rightly suspected was tuberculosis. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

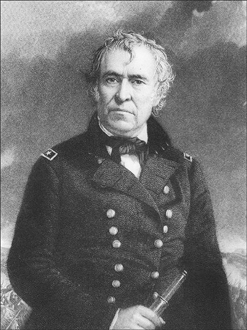

James K. Polk’s pledge not to run for a second term in 1848 offered Clay and the Whigs an excellent chance to capture the White House. Clay’s hopes were dashed when General Zachary Taylor won the Whig nomination. (Library of Congress)

Horace Greeley, the eccentric editor of the New York Tribune, was Clay’s unofficial campaign manager in the final bid for the presidency. By the time of the Whig National Convention, Greeley knew that Clay’s chances were less than slim. (Library of Congress)

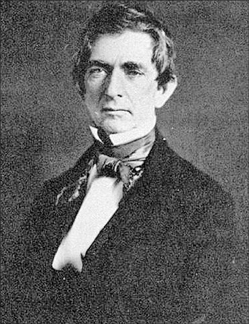

Kentuckian John Jordan Crittenden had been Clay’s most cherished friend for years, but Clay’s discovery that Crittenden was working behind the scenes for Taylor in 1848 estranged them. (Library of Congress)

This cartoon took a blunt view of Clay’s treatment at the hands of his supposed friends in 1848, comparing their furtive desertion of him for Taylor to Caesar’s assassins. (Library of Congress)

Although increasingly ill by the time he sat for this photograph, Henry Clay still displayed some of the spark, especially in his eyes, that made him a charismatic leader for a half century. (Library of Congress)

A fellow Whig and often a fierce rival, Daniel Webster cooperated with Clay when it mattered most during the compromise debates in 1850. (Library of Congress)

By the time this photograph was taken of John C. Calhoun, he and Clay no longer spoke socially. Calhoun was now near death and had become a radical sectionalist who reflexively opposed any measure put forth by Clay. Nevertheless, the two met one last time when Clay visited Calhoun as he lay dying. (Library of Congress)

New York senator William Seward was a protégé of Thurlow Weed and no friend of Clay’s. Seward opposed Clay’s compromise plan in 1850 and provocatively told the Senate that there was a “higher law” than the Constitution. (Library of Congress)

Pennsylvanian James Buchanan was a Senate colleague for many years and frequently bantered with Clay during proceedings. He was among those who marveled over Clay’s return to the Senate in 1849. (Library of Congress)

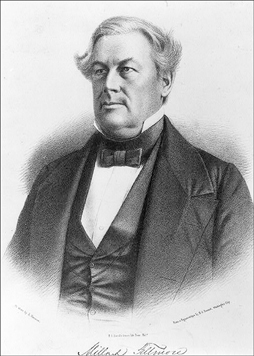

A self-made man much like Henry Clay, Millard Fillmore became president when Zachary Taylor suddenly died. Clay admired Fillmore’s honesty and candor, rare traits in career politicians, and was grateful for the new president’s support in the fight for the Compromise of 1850. (Library of Congress)

Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas ultimately became the principal architect behind the Compromise of 1850, but he expressed open admiration for Clay’s efforts and praised his patriotism. (Library of Congress)

In one of the most famous depictions of Henry Clay, he addresses the Senate during the debates on his compromise proposals in 1850. (Library of Congress)

Although a Whig ally, Maryland senator James A. Pearce accidentally destroyed Clay’s complex plans just prior to the Senate vote on the compromise package at the end of July 1850. (Library of Congress)

In this 1860 reproduction of an 1852 lithograph depicting the important statesmen who had saved the Union in 1850, the engraver made a significant change. Clay remains prominent at just left of center, holding his customary cane. Daniel Webster stands to the right with his hand resting on the scroll. Yet John C. Calhoun, the third member of the Great Triumvirate, has been replaced by Abraham Lincoln in the middle, despite the fact that Lincoln was out of office from 1848 until his election to the presidency in 1860. (Library of Congress)

Lucretia Clay’s cousin, Thomas Hart Benton, began his political career as a staunch ally of Henry Clay but ultimately became a Jacksonian, making him Clay’s bitter enemy. In the end, though, Benton conceded that the “Corrupt Bargain” charge had been trumped up for political purposes. (Library of Congress)

Artist Robert Weir’s painting captures Clay’s final communion as administered by Senate chaplain Charles M. Butler and witnessed by Clay’s servant James Marshall. Thomas Hart Clay arrived shortly afterward to take his father home from Washington, and though Clay briefly rallied, he never left his rooms again. (Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society Collections)

Clay died on June 29, 1852, with Tennessee senator James C. Jones and Thomas Hart Clay at his bedside. (Library of Congress)

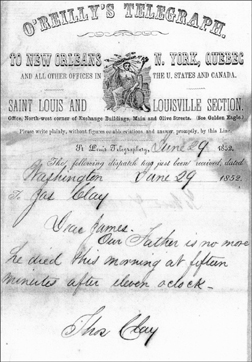

Thomas Hart Clay dispatched this telegram to his brother James shortly after their father died in Washington. (Library of Congress)

Henry Clay lay in state in his unusual human-shaped coffin at numerous stops on the funeral journey back to Lexington. The plate covering his face could be removed for viewing, but the practice was discontinued after the early part of the trip. (Courtesy of Ashland, The Henry Clay Estate, Lexington, Kentucky)

Clay’s funeral in Lexington featured a spectacular and lengthy procession from Ashland to the Lexington Cemetery. Thousands crowded into the town to view the ornate hearse drawn by impressive horses and tended by liveried groomsmen. (Courtesy of the University of Kentucky)

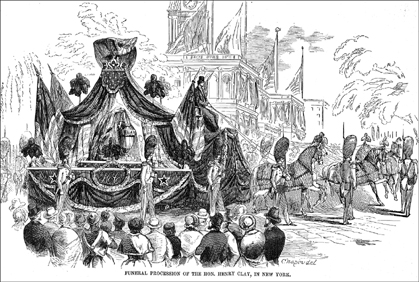

New York was one of the many cities that held elaborate funeral ceremonies for Clay weeks after he had been laid to rest in Lexington. The urn in the funeral carriage symbolized Clay’s presence in the New York ceremony where thousands lined the route to pay their respects. (Courtesy of the New York State Library)

Weighing those encouraging words, Clay took comfort that he had blocked the Wickliffes’ drive to supplant him. Robert Wickliffe, Jr., did not become Harrison’s private secretary (though he did trail him to Washington as part of the new president’s entourage), and Charles A. Wickliffe did not become postmaster general.

Two things did worry Clay, though. One was that Harrison might remain “apprehensive that the new Administration may not be regarded as his but mine.” Clay was concerned that “artful men for sinister purposes will endeavor to foster this jealousy,” and he was determined to dispel any reason for it.49 The second matter that concerned him was Harrison’s health. Despite Old Tip’s repeated claims of vigor, Clay was not so sure. Others also noticed that something was not quite right with the old fellow. After a public reception during the Kentucky trip, one person in attendance thought that Harrison appeared “pretty well worn out.”50 Clay was even more plainspoken. “I think the strength of his mind is unabated,” he said, “but his body is a good deal shattered.” He repeated the observation using the same word, “shattered,” to John Quincy Adams a couple of weeks later in Washington, a sign that the state of Harrison’s health was much on his mind.51

AS CLAY PREPARED to leave for Congress, James abandoned his Missouri farming experiment and returned to Ashland. A year earlier, he had made a prolonged visit to Natchez, where Clay suspected that he had “gotten involved in some love affair,” but no girl was ever mentioned, and James returned to Kentucky alone. Clay was relieved to have him back in any case, since he trusted James to handle business at Ashland while Thomas was occupied with starting up his hemp and bagging business. Thomas had high hopes for success, although he was finding it difficult to secure capital during hard times, and Clay began staking him with hefty advances, generosity that would prove to be a serious mistake.52

Clay and his slave Charles Dupuy left Ashland on November 26 for Washington. Reaching the capital on December 6, he settled into his rooms at Mrs. Arguelles’s and began catching up on his correspondence, a sign that the first of his three campaigns having succeeded—the one to elect Harrison—it was time to commence the other two, promoting his candidacy for the presidency in 1844 and enacting the Whig program. He called on Van Buren at the White House and received John Quincy Adams for a friendly chat. These were not merely cordial rituals but had the purpose of surveying the ground and reading political prospects. Disappointed Democrats would be up to no good, he concluded, and he mentioned the need for a special session of Congress.53

Van Buren’s humiliating defeat led John C. Calhoun to believe that he could be the Democrat nominee in 1844. He itched to run against Henry Clay, who he suspected had obtained Harrison’s blessing as his successor, and like the Kentuckian, he began laying the foundation for his bid early. On December 15, 1840, he walked into the Senate chamber and heard Clay arguing for the immediate repeal of the Subtreasury, just a half year into its existence. Calhoun countered with what amounted to a stump speech not only defending the Subtreasury but exalting Jeffersonian principles of limited government. Clay knew what this was about. Calhoun was giving notice that he would lead the opposition against the Whig majority with every weapon at his disposal.54

Clay soon left Washington for New York, the professed purpose of the trip being to visit three of his grandsons (James Erwin, Jr., Henry Clay Erwin, and Henry Clay Duralde) at their private school on Long Island. When Clay and Charles Dupuy checked in to the Astor House in Manhattan, most people realized that politics would also play an important part in this visit. Editor James Gordon Bennett quipped that the boys on Long Island were “not the only grandchildren that brought Mr. Clay to New York.” Bennett listed every prominent Whig in the city as eagerly seeking Clay’s favor, and indeed many did call on Clay, hoping that he could use his influence to gain them a place in the new administration.55

Clay and Charles left New York on Tuesday, three days before Christmas. They also left the boys and their classmates in the care of Peter Porter, who treated them over Christmas to the circus and a tour of the Bowery.56 As for Clay, he boarded the Jersey City ferry to catch the train for Philadelphia and found himself in the company of Caroline Webster and Congressman Edward Curtis’s wife. They were on their way to Washington to join their husbands. He “greeted them with great cordiality, and expressed his delight in having their company to the capitol [sic].”57 That was likely true, if incredible, or at least it was a deceptive gesture of instinctual gallantry: Clay knew that Webster was going to prove a troublesome rival in his bid for the presidency, and Clay would soon have cause to loathe Edward Curtis. But in the brisk breezes that buffeted the Jersey ferry that December day, Clay was chivalrous and charming. At least by all appearances, the trio made for delightful company, but it was perhaps an omen that by the time he had reached Wilmington, he had become so ill with his nagging cold that he was in his bed for almost two days and otherwise confined to a room until he felt well enough again to travel, which was not until December 30.58

He arrived in Washington in time to attend Martin Van Buren’s final New Year’s Day reception, an event he would not have missed for the world. The weather was stormy and miserable, sleet mixing with snow to pelt people as they arrived, and attendance was thin as a result. John Quincy Adams heard Clay tell Van Buren “that nothing but devotion to him could have induced him to come out from his lodgings on a day such as this.” Adams interpreted the remark as an example of the Kentuckian’s sarcasm. “Clay,” he sniffed, “crows too much over a fallen foe.”59 Yet there was plenty of evidence to indicate that Clay was sincere. His relations with Van Buren had always been civil and often quite affable. Even the Democrat press had noticed how Clay “was inspired with the greatest respect for the man, though he detested the magistrate.”60 Clay likely felt sorry for the political antagonist he also regarded as a personal friend, a man sniggered at as Sweet Sandy Whiskers and unfairly maligned for turning the White House into a sumptuous palace. Now at Van Buren’s final grand levee, the falseness of the latter charge was laid bare. The place was in shambles, the East Room’s wallpaper peeling, its large carpet threadbare, and the satin damask nearly worn off the seats of the chairs.61 Henry Clay stood at the center of the East Room amid a glittering array of bejeweled women impatient to catch his eye and laughing men eager to shake his hand, a cluster of people larger than that around Van Buren. Clay did not feel well, and rather than crowing, he was likely sincere in what he said to the little man who at the end had been forced to rely on John C. Calhoun, of all people, for political sustenance. This last party, ruined by the weather, lightly attended by Washington society, and lacking even meager refreshments, was no occasion for gloating. It all just seemed rather sad.62

IN THE JANUARY term of the Supreme Court, Clay joined Charles L. Jones and Daniel Webster to represent Robert Slaughter in the case of Groves v. Slaughter, a complicated dispute involving slavery, the state of Mississippi, and the validity of promissory notes. In fact, Groves v. Slaughter was about two legal disputes. One concerned Robert Slaughter, a slave trader who was demanding payment for slaves he had sold into Mississippi in 1836. Groves, who had endorsed a promissory note for the purchaser, claimed that the transaction violated the part of the Mississippi constitution prohibiting the introduction of slaves into the state “as merchandize” after May 1833, a move designed to prevent the drain of capital from the state. Groves insisted that because the transaction was illegal, he was under no obligation to pay Slaughter, who then sued him in the federal Circuit Court of the Eastern District of Louisiana. When the circuit court upheld Slaughter’s claim, Groves petitioned the Supreme Court.63

Clay, Webster, and Jones were in part interested in recovering the money owed to Slaughter, despite its unsavory nature, because a promissory note was still a legal contract that could not be disregarded without imperiling all commercial transactions. Yet a more significant issue than debt collection arose from the possibility that Mississippi had violated the U.S. Constitution by presuming to regulate interstate commerce, a power reserved to Congress. Because the interstate commerce in question had been in slaves, the case became a sensitive test of the balance between federal and state power and had the potential to affect the institution of slavery itself. As John Quincy Adams succinctly discerned, “The question is whether a State of the Union can constitutionally prohibit the importation within her borders of slaves as merchandise.”64 The implications were therefore staggering. In determining the validity of Slaughter’s promissory note, the Court could have been forced in 1841 to delve into a titanic issue: the legal status of slaves as property and as people. Doing so would have had the same sort of impact on the slavery controversy that the Dred Scott decision did sixteen years later. In short, such a decision could have accelerated an already angry debate over slavery, possibly to a violent conclusion.

That was why a case that seemingly involved only the sordid business of slave trading and the mundane matter of an unpaid bill featured celebrated and high-powered legal talent on both sides. In addition to Clay and Webster, Slaughter’s team included Walter Jones, a legal genius renowned for his encyclopedic knowledge and something of an eccentric in dress and speech. Despite a high, thin voice so hushed as to give the impression that he was nodding off during his arguments, he had “piercing” eyes and an exceptional talent for lodging brief, pointed presentations.65 Representing the State of Mississippi were Henry D. Gilpin, the U.S. attorney general (and second husband of Clay’s old friend Eliza Johnston), and Mississippi senator Robert J. Walker.

Oral arguments began on February 12, 1841, a Friday, and continued until the following Friday, drawing large numbers of “distinguished counselors … and scores of men eminent in other professions” to the Court’s chamber on the ground floor of the Capitol’s north wing, both to see the celebrity lawyers at work and because of the case’s possible significance. The presence of Clay and Webster accounted for “the ladies [who] occupied all the vacant seats of the Court-room and crowded everyone but the Judges and counsel out of the bar.”66

As was his custom in the Senate, Clay did not speak from a prepared text but relied on brief sentences to serve as cues. He spoke for about three hours, and the spectators remained attentive throughout his lengthy remarks. He pointed out the economic repercussions that would result from allowing Groves to ignore the debt, for the precedent would not only affect Slaughter but would also involve “more than $3,000,000, due by citizens of the state of Mississippi, to citizens of Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky and other slave states.” He assessed the legal implications of canceling the contracts that promissory notes represented and provided a detailed analysis of the Mississippi constitution’s intent and the Mississippi legislature’s actions to show that not until 1837, the year following Slaughter’s transaction, did the legislature pass a law enforcing the prohibition.

The easiest way to win the case was to argue that Mississippi had overreached its authority and therefore could not have made the Slaughter transaction unlawful. Yet Clay was troubled by the possibility of invoking the interstate commerce clause to curb a state’s right to control its own affairs, especially regarding slavery. Doing that could trigger a dire response throughout the South. In his notes, he insisted that “Congress has neither the power to disturb the existing institution [of slavery] or to establish it within a State” and “Congress cannot therefore do what the Abolitionists seek.” If congressional control over interstate commerce could be used as Adams had mused—that is, to regulate or otherwise impinge upon the institution of slavery—it would become a powerful weapon in the abolitionist arsenal and might spur southerners to a calamitous reaction. Indeed, Robert Walker “threatened tremendous consequences” if the states were brought to heel in this way.67

As it turned out, the justices were also apprehensive about tackling the sobering issues of slavery and states’ rights, and when they handed down their decision on March 10, a majority managed to dodge those questions by essentially agreeing with Clay. Because there had been no legislative statute enforcing Mississippi’s constitutional prohibition on importing slaves, the Court ruled that the prohibition had not been in effect at the time of Slaughter’s transaction. Upholding the circuit court’s decision made it “unnecessary to inquire whether this article in the constitution of Mississippi is repugnant to the constitution of the United States.”68 Chief Justice Roger Taney even went so far as to say that the issue of exclusive federal control over such a matter was “little more than an abstract question which the court may never be called on to decide.”69

That, of course, turned out to be a stunningly mistaken prophecy, as Clay feared. Taney could not have imagined that eventually the political system would bring something very much like this question to the Court and that he himself would see it as more than an abstraction. Sixteen years later, Taney would feel compelled to decide the question, come hell or high water. In due course, just as Clay had feared, both hell and high water came with a vengeance.

HARRISON OFFERED WEBSTER a place in the cabinet, as Clay recommended, but he gave him the choice of Treasury or State, against Clay’s advice. Clay did not know about this, because Webster chose State, but it indicated that Harrison was inclined to give only lip service to his counsel, and in other appointments he soon gave Clay reason to be concerned. Though his friends were prominent in the new administration, with Crittenden appointed attorney general and John Bell secretary of war, it was disconcerting to learn that Tom Ewing was moved from postmaster general to Treasury to make a place for Frank Granger. That was Webster’s doing, and the change was the first sign that the New Englander might be able to exert more influence from within the administration than Clay could from outside it.

The appointment that Clay most wanted was that of his friend John Clayton. Clay had wanted Clayton at Treasury, but with that taken, he was prepared to settle for secretary of the navy. When Harrison balked, Clay pressed the matter, unwisely ignoring his own advice about not exciting Harrison’s sensitivity over who was really in charge. In late February, Harrison traveled to Richmond for a rest before the inauguration and visited attorney James Lyons, a staunch supporter who was the president of Richmond’s Tippecanoe Club. According to Lyons, Harrison was quite agitated about Clay’s behavior, which he described as violent and overbearing to the point where Harrison had barked: “Mr. Clay, you forget that I am the President!”70

Possibly Harrison’s sharp remark was caused by the dispute over Clayton, but it is also possible that Harrison never said it. Lyons, like John Tyler, was a former Jacksonian Democrat who had become a Whig when repelled by Andrew Jackson’s overbearing manner. Yet Lyons had never really deserted fundamental Democrat principles, and his most notable contribution to the 1840 campaign was a states’ rights manifesto called the Whig Address, which incongruously repudiated Whig principles by denouncing the protective tariff and declaring a national bank unconstitutional. Moreover, Lyons had asserted that Harrison condemned the Bank too.71 Clearly Lyons was no friend of Clay’s. In addition to being the only source describing Harrison and Clay as at loggerheads before Old Tip’s inauguration, Lyons did not make the claim until almost forty years later in a letter to the New York World, a struggling New York daily (Joseph Pulitzer would purchase it in 1883). As we shall see, there are other reasons to suspect both Lyons and the statements in his 1880 letter.

When Harrison gave Navy to North Carolinian George E. Badger, Clay put the best face on it, hoping that Clayton’s rejection was “the result of perhaps rather an imp[r]udent rule adopted by Genl Harrison, in respect to the geographical distribution of the members of his cabinet” rather than any intentional slight directed at him. Nevertheless, the president-elect’s intransigence hurt Clay’s feelings, and he forlornly told Clayton, “Your disappointment will be far less than my own.”72

By far, however, Clay’s most telling disappointment concerned the collector of customs for New York, a position that many regarded as second only to the presidency in the vast patronage it commanded. Clay wanted his supporter Robert C. Wetmore to receive the appointment, but rumor had it that Harrison intended to select Edward Curtis, a former Antimason whom Peter Porter described as “a shrewd and managing man.” Clay had little reason to support someone who had worked hard to defeat his nomination at Harrisburg.73

Curtis had Weed and Seward in his corner, however, and he had long been a Webster man, so he had a self-interested advocate in Harrison’s inner circle.74 Having Webster’s supporter in the collector’s post where he could spread the patronage wealth for the New Englander was a chilling prospect. New York Whig leaders apparently realized this might be the main obstacle to obtaining Clay’s consent, and Thurlow Weed met with Peter Porter to hint that if Clay withdrew his objections, Curtis would support him in 1844. Clay was not persuaded. If anything, he was all the more suspicious of a man so willing, as he had put it, to row one way and look the other. “How can such a man as Curtis be trusted?” he asked. “My determination not to cooperate in his appointment is irrevocable.”75

It soon became apparent that his cooperation was immaterial, and in reaction to the slight, Clay lowered his head and resigned himself to the inevitable. Curtis received his appointment after Harrison’s inauguration, and Clay’s public pose was an obvious attempt to preserve his dignity. He was determined not to let the setbacks over Clayton and Curtis ruin the opportunity presented by a Whig Congress with a Whig president. “We must support this administration,” he said, “or rather, I should say, we must not fall out with it because precisely the friends we could wish had not in every instance been called to the cabinet. I have strong fears & strong hopes. And sometimes the one & sometimes the other predominate.”76

The weather in Washington was gray and raw on March 4, but it did not dampen the enthusiasm of the large crowds in the capital for Harrison’s swearing in. A special session of the new Senate came to order at 10:00 A.M., adopted a resolution electing Alabama’s William R. King president pro tem for the ceremonies of the day, and appointed Henry Clay to administer the oath to him.

At 11:00 the diplomatic corps and Supreme Court justices entered the chamber, and thirty minutes later, King in turn administered the oath to John Tyler, who delivered “an eloquent and able address.”77 At least Tyler’s speech was brief, something everyone would remember with a measure of gratitude later that afternoon. Harrison entered the Senate chamber at a quarter past noon to be escorted to the East Portico of the Capitol, his arrival there greeted by a thunderous ovation and prolonged cheers from the crowd below before everyone settled down. As it happened, they had to settle in, for Harrison commenced an interminable inaugural address of more than eight thousand words, going on for nearly two hours, to this day the longest in presidential history. Webster had tried to tidy it up with careful cuts, but Harrison was intent on showing both his erudition and his stamina, forgetting the connection between brevity and wit, and disregarding the fact that even a young man, bareheaded and lightly clad, should not stand outside in the snow for two hours.

When Roger Taney was finally able to administer the oath, the cheers and applause that followed were likely as much an expression of gushing relief as a tribute to Tippecanoe. Cannon fired from Capitol Hill, echoed by others in remote parts of the city, “and the crowd dispersed.” After the ordeal, it most certainly did.78

The new Senate of the Twenty-seventh Congress returned to its chamber and was about to adjourn when Willie Mangum gained the floor to introduce a resolution to be taken up the following day. It was a move to fire Democrats Francis Preston Blair and John C. Rives as printers to the Senate. Clay was behind this. On February 19, he had stoutly opposed the dying Democrat majority’s effort to reappoint Blair and Rives and thereby saddle the incoming Whig Congress with men “utterly odious to those who were in a few days to succeed to the possession of the Government.”79 Mangum’s resolution dismissing them was to be the first initiative undertaken by the Whig majority, and it set off a lengthy and acrimonious debate that stretched over several days and ultimately got out of hand. Democrats cried foul over the Whig effort to break a two-year contract made in good faith with Blair and Rives. Clay countered that the appointment of these men had been an imperious “act of power—pure, naked unqualified power,” but moreover he insisted that they should be fired because of Blair’s “notoriously bad character.”80

The move was personal for Clay, because his break with Blair had been ugly in the way that only a rupture between old friends could be, veined with traces of betrayal and deceit. Yet Whigs who had no personal history with Blair felt equally outraged at the prospect of keeping “men in their employ whose only language toward them has been that of contumely and insult.”81 Clay was therefore not alone in condemning the Washington Globe and its pugnacious editor. For years Blair had alternated between vicious language and a mocking sneer to mount ferocious attacks on Andrew Jackson’s opponents in general and Clay in particular. In the days when Calhoun was friendly to Whigs, even he had described the Globe as “filthy and mendacious,” and it was understandable that the Whig majority would not want to subsidize that press with a lucrative printing contract.82

On March 9, Clay watched in growing anger as Connecticut’s Perry Smith accused him of implying that all senators who had supported Blair were also “infamous.” Then Alabamian William R. King reminded everyone of Clay’s personal friendship with Blair before their break and insisted that the editor’s character would compare favorably with Clay’s. The likes of Perry Smith did not merit his notice, Clay hotly responded, but King, “who considers himself responsible,” was quite another matter. King, in fact, had “gone one step further … to classify me with the partisan Editor of the Globe.” These remarks by King, Clay shouted, were “false, untrue, and cowardly.”

Whispered talk had long painted King as a homosexual, although the only evidence for the insinuation was a tendency to dandified dress and his close friendship with another confirmed bachelor, James Buchanan, with whom he lodged at Mrs. Ironsides’s on Tenth and F streets.83 The rumors, along with the heightened sense of pride common among southerners, made King touchy, as John Randolph had been, and Clay’s words brought him to his feet amid a raucous clamor that rapidly died away. The dark look on King’s face clearly indicated that Clay’s remarks, “short and intemperate” in the estimation of John Quincy Adams, had crossed a line. “Mr. President,” King said in measured, terse tones, “I have no reply to make—none whatever.” He sat down. Nobody moved. The chamber was slipping into reflective silence when Perry Smith piped up to ask if he really was beneath Clay’s notice. “Not at all,” Clay snapped. Smith paused to digest the disdain and then embarked on an embarrassing ramble of self-pity and awkward sarcasm, but nobody was likely listening to him. The entire body of senators sat as though dealt a hard blow. Clay’s words—“false,” “untrue,” and worst of all, “cowardly”—hung in the air like an unpleasant odor. William Preston rose to say that it was regrettable “that any thing should have occurred that should have driven honorable Senators to do any thing inconsistent with parliamentary decorum,” but the observation at this point was a remarkable understatement. In fact, King had taken the time during the exchanges following his remark to scribble a note. He motioned for Lewis Linn of Missouri to accompany him from the chamber, and after adjournment, Linn appeared before Clay with a piece of paper, apparently King’s note.84

That evening rumors raced through the capital that King had challenged Clay to a duel. Reports also told of their being arrested, but actually only King was briefly detained for fear that he would do something rash. Both men posted bonds with D.C. justices of the peace as surety that they would not assault each other.85

Bennett’s Herald had great fun with this set-to, suggesting that sending King and Clay on a journey together over New York’s wretched roads to Albany would make them “meek and gentle as new-born kittens,” but the incident was unseemly and embarrassing for everyone, most of all for Clay, who had lost his temper and behaved badly. The Senate dismissed Blair and Rives on a 26 to 18 vote, but the affair meanwhile gave rise to wild stories and rising invective throughout the country. In New England, newspapers reported that a duel had killed Clay and left King mortally wounded. Democrat papers branded Clay a “blackleg and demagogue” and ridiculed his pledge not to fight as that of a man “who calls on his friend to hold him by the coat tail, to keep him from striking his antagonist.”86

Linn, acting for King, and Clay’s friends William Archer and Preston worked together to orchestrate a public reconciliation on March 14 near the close of the special session. Preston rose in the Senate to describe the affair as a misunderstanding, which opened the way for Clay to admit that he had been wrong in his interpretation of King’s remarks and therefore wrong to lose his temper. He apologized. King followed suit, assuring the Senate that he had meant no offense to his friend from Kentucky. As King was concluding his remarks, Clay was already on his feet, striding across the chamber with his hand out. King took it, and a smattering of applause grew into a thunderous ovation from their colleagues, spectators in the gallery joining in.87

The happy conclusion to this incident could not disguise the fact, however, that everyone was on edge in this new arrangement where Democrats, accustomed to being a majority, and Whigs, eager to act like one, were bound to clash. But Clay’s overreaction suggested that larger problems were nagging him. The quarrel with Democrats over printers was irritating, but his disagreements with William Henry Harrison had become exasperating. To his thinking, those differences threatened to squander the victory of 1840.

CLAY HOPED THAT the close of the brief special session of the Twenty-seventh Congress would be quickly followed by another “at the earliest convenient & practicable day” to begin enacting elements of the Whig program. He had begun floating the idea shortly after the election, and in early 1841 he openly stated that to oppose the extra session was to favor “the continuation of Mr. V. B’[s] Admon [sic] 12 or 18 months after its constitutional termination.” As Tom Corwin had said, to win the election and do nothing threatened to make liars of them all.88

But Harrison dithered, and soon enough it was easy to see why. His cabinet was evenly divided on the issue, but Webster’s negative vote most influenced the president. From their first interview to discuss Webster’s joining the administration, Dan’l had been anything but godlike, adopting instead a submissive demeanor toward Harrison that first ingratiated him to the president-elect and then gave him increasing clout with the president. That Harrison, a proud stylist, had consulted Webster on his inaugural address was one sign of that growing power, the selection of Curtis and Granger was another, and the president’s attitude about the extra session yet another. Webster’s motives were mixed, but his plans for the presidential contest in 1844 were certainly foremost. Blocking the extra session meant that Clay would have no reason to remain in Washington, and Webster could solidify his position with Harrison to guide the administration for eight months unchallenged. Deprived of a forum until December, Clay’s tactics for 1844 would suffer a serious setback.89

Reasons other than a desire to keep pace with Webster, or even an obligation to address the needs of the people, must have filled Clay with a sense of urgency over the extra session. Given everyone’s observations about Harrison’s health, there was the distinct possibility that the new president could become ill enough to elevate John Tyler to an acting presidency, at least temporarily. Clay had never said a word to anyone about John Tyler, for it would have been most imprudent to do so, but he had to be concerned that Tyler’s attitudes about Whig principles did not necessarily mesh with his own, or Harrison’s for that matter. During the campaign, there had been troubling signs. For instance, Pittsburgh Democrats, in a ploy to embarrass Tyler, had requested that he write a letter spelling out his true opinions on the Whig program. Tyler complied, but at the last minute he had congressional Whigs vet the communication. To a man, they said not to publish it.90 Clay would have known about this cynical maneuver to disguise what Tyler actually believed. It was unsettling.

On March 13, Clay took the liberty to write to Harrison about the need for an extra session and even enclosed a draft proclamation for Harrison to use in calling one. It was a risky move, to be sure, and that Clay was willing to chance it indicates how anxious he was to have Congress get to work as soon as possible. But it immediately proved to be a dreadful mistake. Already testy about what he perceived as Clay’s meddling over appointments, Harrison bristled. There was to be a state dinner that evening where Clay and Harrison could have conversed, but the president was angry and instead dashed off a note to Clay that began with a prickly “My dear friend” and went on from there: “You use the privilege of a friend to lecture me & I will take the same liberty with you—You are too impetuous.”91

Newspaper reporter Nathan Sargent claimed that Harrison’s note enraged Clay not only because of its tone but because it all but instructed him to communicate in the future with the administration only in writing. “And it has come to this!” Clay was said to have shouted, though Sargent is the only source for this scene. Despite not feeling very well, Clay kept his dinner engagement at the White House that evening, which was a large party attended by scores of prominent men. In the wake of his and Harrison’s exchange, it must have been at best an awkward event for Clay.92 In any case, he bitterly realized that he was not only beaten on this issue but was also confronting a nearly total triumph by Webster to control the administration. Clay swallowed his pride to repair the damage. He wrote to the president to confess that he was “mortified” by the suggestion that he was dictating to him. “There is danger of the fears, that I intimated to you at Frankfort, of my enemies poisoning your mind towards me.” He rather helplessly felt the need to revisit the controversy over Curtis: he claimed that he had not said Curtis should not be appointed, which was not altogether true, but he hedged by explaining that he had merely stated his opinion that Curtis was unworthy of the post. If expressing his opinion meant that Clay could be accused of dictating, there was little he could do about it. He told Harrison not to trouble with answering.93

When Harrison did not respond, the silence from the White House sent a clear message, and two days later Clay left Washington for home. He had gotten only as far as Baltimore when he became seriously ill. It has never been clear what was wrong with him, but he later described the malady as an “attack … more severe than I was aware of at the time.”94 His ailment was serious enough to stop his trip and confine him to a room at Barnum’s Hotel for almost a week. Very likely the repeated humiliations, many of them now embarrassingly public, were finally taking their toll.95

On the very day that Clay left Washington, Harrison abruptly relented and issued a call for the extra session, although a disturbing consultation with his cabinet over the plummeting economy, not Clay’s influence, was the reason he changed his mind. Biddle’s United States Bank of Philadelphia had suspended specie payments, western state treasuries were empty and their governments on the verge of debt repudiation, and Treasury secretary Ewing brought in figures that showed the federal government’s already substantial deficit would soon be bloated by more than 11 million additional dollars. The imperative of an appropriations bill and finding the money to fund it compelled the administration to summon Congress, the sooner the better. At this point, even Webster agreed. Harrison called for Congress to meet on May 31.96

A week after issuing the proclamation, Harrison came down with a chill and quickly developed pneumonia. Office seekers and official functions had dogged his days, and his rash decision to deliver his lengthy inaugural address in bad weather further weakened his already fragile constitution. The exhausted old man died on April 4, only four weeks into his term, the shortest presidency in American history.

Tippecanoe was dead, and Tyler Too was now the president. Andrew Jackson was ecstatic. Harrison, he said, did not have the energy to withstand office seekers. Jackson speculated that Old Tip had been resorting to “stimulants” to keep pace. His death was the work of a “divine … Providence,” according to Jackson, a heavenly decree to kill this president in order to save the Union and the republican system.97