Tierce

Flammescat igne caritas accendat ardor proximos …

MAY THE FIRE OF LOVE BURN EVER BRIGHT, ENKINDLING OTHERS WITH ITS FLAME.

HYMN FOR TIERCE FROM MRS QUIN’S Day Hours

The Angel and the Shepherds The scene is set in a field in winter. The angel stretches out his hands to comfort the frightened shepherds, who are kneeling with their hats doffed. His presence seems to warm the bleak landscape. A few sheep are straying about.

Full border of conventional flowers, poppies, cornflowers, sheaves of wheat, and ivy leaves, painted in colours and heightened with gold. Grotesque of a bearded man’s head without a body, but with arms and legs growing from it.

MINIATURE FACING THE OPENING OF TIERCE IN THE HORAE BEATAE VIRGINIS MARIAE, FROM THE HOURS OF ROBERT BONNEFOY

Peter brought up the milk. He was still swollen-eyed and lightheaded with tiredness and want of sleep, but he had bathed, shaved, and put on clean clothes. ‘I want to pay my respects,’ he might have said, ‘my very profound respects.’ On top of the milk can was a bunch of clover. He had picked it because the cow, Clover, had calved in the night. Night! Two o’clock this morning, thought Peter. Though he could not help feeling happiness and relief about the calf, in his heart was the same unbearable ache of loneliness.

As he and Mrs Quin had hoped, it was a heifer calf. There would be seven in the herd now – And this one looks a beauty, thought Peter. That was not all – the threshing yesterday had yielded an average of one and a half tons of wheat for every acre. ‘Not bad,’ said Peter. He would have to sell his wheat, as he had no room to store it, but he would keep the straw. Yesterday at this time there was only promise; today this augmentation. I must be more than two hundred pounds richer, thought Peter, and again it was not only that: the corn and the calf were proof of his work and planning – And I was quite wise, thought Peter, surprised – the planning and the work of every day.

In spite of his sadness, of knowing what must happen, those two words every day seemed that morning to Peter the most beautiful in the world, heartlessly beautiful when he thought that for Mrs Quin these were not every days but the last. Tomorrow, or the next day perhaps, they will bury her, thought Peter. He could not believe it. The marigolds along the kitchen-garden path brushed dew on his gaiters – he, as she did, liked boots and gaiters better than gumboots – the sun shone on the dew, drawing out sparkles, throwing long shadows; he had never seen the garden look more alive, heartlessly alive, thought Peter. It should have been grey, shrouded for this last day. That was written now in capitals in his mind: LAST DAY, but smoke was going up from one of the chimneys; the kitchen fire was lit. It was like a calm message from the house; last days too are every day, said the message.

Anyone walking up from the China Court kitchen garden to the house in high summer must come upon the sweet peas behind the low wall, a thick hedge of them making a confusion of colours: whites and creams, limpid pinks and mauves, queer hot-looking purples, magenta with white threads, salmon pink, deep-smelling wine. It is Mrs Quin’s habit to pick them in the evening when it is cool, and every night long, in August, a bunch sits in a pail on the path to catch the dew.

Now Peter stopped bewildered; the pail was in front of him. But – they have been picked, he thought.

‘Haven’t they always been picked?’ He could almost hear Mrs Quin saying it, but who had picked them? Cecily? Cecily would scarcely have had time but, It must have been Cecily, thought Peter reasonably.

He smelled them, going down on one knee; then he brushed the grains of granite dust from his breeches and went on up to the house and around to the kitchen, treading on the grass so as not to disturb the quiet, then stopped short in the doorway.

‘If he had seen me at any other time, he would never have liked me,’ said Tracy afterward. ‘He wouldn’t have let himself like me,’ and it was true that he would not have spoken to her if he had seen her as she had first appeared to Cecily that early morning; in her travelling suit and matching coat she would have been like any of the girls in the world he had run away from – St Omerland he called it now – and instinctively, he would have run away from her too, but now she had tied one of Cecily’s aprons around herself and was getting breakfast – ‘helping Cecily,’ as she would have said twelve years before. As he saw her now she was standing at the table slicing bread, too absorbed to see him. Behind her the range was well alight, making the gentle rushing sound of a fire drawing well up the chimney; the front was open and the glow filled the room. There was a smell of breakfast, and Peter felt almost faint remembering the mug of coffee, half warmed and full of grits, that he had snatched before milking; the mixture, that seemed nauseating now though he did not remember tasting it, of a slab of bread gone stale and oily sardine. When he brought up the milk he often stayed for a gossip with Cecily, ‘and to get a cup of good hot tea inside him,’ said Cecily, but the smell that assailed him now was of coffee, fresh and hot, of milk simmering, of bacon and fresh toast, of warmed china. ‘It wasn’t fair,’ said Peter afterward.

To Bella, China Court’s kitchen has no charm at all; it is simply old-fashioned, muddled, and deplorably cumbersome. ‘And there is the big pantry, and all those silver cupboards and linen presses, the cellars and storeroom down in the basement, the knife room and that enormous scullery, with wooden sinks!’ cries Bella.

‘A wooden sink never breaks or chips anything,’ says Mrs Quin, but even she has to admit she would like some of the kitchen furniture a little smaller.

The Eagle range has an array of plates, a spit, and has two vast ovens, the second used for warming china and drying kindling; Cuckoo, the little cat, always tries to have her kittens there.

The dresser is on the same scale and holds sizes of dolphin-handled dish covers, copper moulds, japanned trays, and china, while its drawers are always bursting with mysterious odds and ends, and there is an untidy pile of recipe books on its bottom shelf. The table, ‘big enough for three kitchens,’ says Bella, is scrubbed white and has a coffee-grinder fixed to one end. The kitchen chairs are wooden and there is a rocking chair with a blue cushion. The floor is flagstone with a rag rug on the hearth and there are always plants on the windowsills, geraniums now, but in winter, white chrysanthemums, and early bulbs in spring. On the sills too, the gardeners put their pasties to be warmed for their lunches; there is a great deal of warming, of cloths and bowls, of cream, of yeast and, usually, of a cat on the hearth rug or armchair. Altogether it is a warm, comfortable, spice-smelling place and now to Peter it seemed to emphasize his emptiness and loneliness – and the dirty little kitchen scullery at Penbarrow; he watched almost yearningly as Tracy put the fresh-cut bread ready for more toast and turned the bacon. Who is she? wondered Peter. Someone I don’t know from the village? But she did not look like a village girl. A friend of one of the younger Quins come down? But then, stepping away from him she went to the dresser, opened a drawer and quite certainly took out a tablecloth – As if she belongs here? thought Peter.

She must have sensed that somebody was there and thought it was Cecily because she said, over her shoulder, ‘Shall we have breakfast here in the kitchen?’ and before Peter had time to think, ‘Please,’ he had said, ‘Yes, please,’ and Tracy jumped and turned round.

Always, afterward, she remembered that first glimpse of Peter, a young man gazing at her with such warm approval that it warmed her too. He was smiling at her, but, as she smiled back, the gaze was abruptly withdrawn and, ‘I beg your pardon,’ he said stiffly. ‘Of course you were not speaking to me.’

From the village! This unknown girl was looking at him with eyes that were completely familiar, that he had loved, the unmistakable grey-green eyes that were Mrs Quin’s, but looking at him now from a girl’s face, young and wan as if it were tired – and shocked, thought Peter – dark-shadowed under the eyes and streaked with tearstains. The village! This girl was a Quin.

It was uncommon for Tracy to smile at strangers, however approving, but Peter was right: she was in a state of shock, a turmoil of unhappiness for Mrs Quin, and happiness, because nothing could gainsay the fact that she was back at China Court, ‘but nothing was as I had imagined it,’ she said afterward. For her China Court and St Probus had been halcyoned by distance – and I suppose by how Americans think of England, thought Tracy, as mellowed, picturesque, cosy; she had not been prepared for the wastes of moorland, bleak and grey in the early morning, nor for the harsh plainness of the village, ‘and the house and garden seem so small,’ said Tracy. ‘I had thought they were boundless.’ It’s all so matter-of-fact, she had thought disappointed, and then, strangely, began to be glad – because it makes it real, thought Tracy. Altogether she, like Cecily, was quite out of herself; she had forgotten to put on the polite defensive mask she usually clamped over her too childish face, and now she smiled warmly at Peter and, ‘Are you the milk?’ she asked.

He did not look like a milkman, this tall young man, lean to thinness, in the shabby whipcord breeches and checked shirt. He was looking at her as if he were displeased – Why should he be displeased? wondered Tracy – and he said stiffly, even accusingly, ‘It was you who picked the sweet peas.’

Tracy would normally have been routed at once but, when one defensive person meets another, they recognize each other, like prisoners, thought Tracy, and Peter’s defensiveness only calmed her, so that it was without even the stammer which dogged her in moments of nervousness – and she was always nervous with young men – that she answered, ‘Yes, I picked them,’ and explained, ‘I used to do that with Gran, and Cecily wanted them.’

If I had stayed in St Omerland, Peter was thinking, I should have met girls like this on equal terms. It doesn’t matter how rotten you are, he thought savagely, if you have the trimmings. What trimmings had he? A few cows and stock, a crop of wheat, some silver cups and books in a tumbledown farmhouse – that isn’t even mine, thought Peter. I had better go, he thought, and put the can on the table. ‘Yes, I’m the milk,’ he said abruptly.

‘But you must have a name?’ Tracy was still calm.

‘Peter St Omer.’

‘St O—There was a Lord St Omer here, I remember him. Then are you …?’

‘I’m the fanner at Penbarrow.’

‘But it was Mr—’ She broke off. ‘Of course, that was twelve years ago.’ She lifted her eyes to look at him again. ‘I’m Tracy Quin,’ she said.

‘Tracy? The Tracy?’ asked Peter, interested in spite of himself. ‘But you were a little girl.’

‘I was, twelve years ago,’ said Tracy sadly and she cried, ‘Oh! How could I have stayed away so long?’

‘You seem to have managed it for twelve years.’ Peter was cold again but she did not appear to notice.

‘I let them keep me, let them order me about,’ and she said, more to herself than to him, ‘I don’t think it occurred to me that I could order myself. And all this time I was quite close, in Rome. Why, I have been there nearly two years.’ Her eyes were filling with tears again, but Peter refused to sympathize.

‘You must speak Italian very nicely,’ he said coldly.

‘No. I’m not good at talking to people. I think altogether I was wasting my time. Then Gran wrote to me, but to America; they sent the letter on, too late.’ She stopped, looking down at the table, trying to hold back her tears. ‘Oh! I came as fast as I could,’ cried Tracy. ‘I thought I would surprise her. I came straight on from London. I had to stay the night in Exeter, but I didn’t leave the station and caught the first train.’ The words tumbled out pell-mell. ‘It was a funny little milk train to Camelford and the stationmaster there woke up a taximan.’

‘I heard a car come down the lane and wondered …’ But Peter would not betray his interest and instead, ‘You needn’t have done all that,’ he said. ‘There’s a perfectly good night train from Paddington that puts you out at Liskeard.’

Why was he so unsympathetic and terse? But Tracy was often terse herself, and once again, it had the effect of making her calm and she was able to lift her head and look at him squarely. She had not seen colouring like his before and the red hair, skin brown as a Mexican’s, made her feel like a wraith in her paleness; his eyes were brown too, not easy eyes, and now, not friendly. ‘Please tell Cecily,’ he said, ‘I brought three pints extra for the Horde.’

‘The Horde?’

‘I’m sorry, that was rude of me. It’s my name for Mrs Scrymgeour, Bella, and the others, your uncles and aunts.’

‘You know them?’

‘I know them.’ He said no more than that, but his briefness told Tracy what he did not say, and, Did I like Aunt Bella? she thought. I don’t think I did. ‘Tell me about them,’ she wanted to say but she could hardly ask questions about her own relatives from someone so obviously hostile; instead she put out her hand and touched the bunch of clover on the can. ‘You brought these for Gran?’

The edge went out of his voice – and out of his face, thought Tracy – as he said, ‘The cow she gave me, Clover, had a calf last night.’

‘A calf?’ Tracy sounded as pleased and interested as Mrs Quin herself would have been, and, ‘It’s our first,’ Peter volunteered. He had to tell somebody. ‘But you have other cows as well?’ She seemed really interested, and, ‘We had Clover, Buttercup, and Daisy, Poppy, Pimpernel, Parsley, the beginnings of a real Jersey herd,’ said Peter; then the edge came back, abruptly. ‘But that’s no use now,’ he said.

‘Why is it no use?’

‘Because’ – and Peter said it as lightly as he could – ‘because tomorrow, or the next day, as soon as they read the will, my farm will probably belong to your Aunt Bella.’

‘To Aunt Bella?’ Tracy looked startled. ‘And China Court, the house?’ she asked anxiously.

‘The house too, I expect.’

‘What will she do with it?’

Peter shrugged. ‘Sell it, I suppose. If she can.’

‘Sell it, but she can’t.’ Tracy was incredulous.

‘She can and she will. Bella and Walter or one of the others,’ said Peter, ‘it makes no difference. It will be sold, broken up. I’m sorry,’ he said as he saw the tears really spill over now. ‘I’m sorry but it will.’

‘Gran wouldn’t have let them,’ Tracy whispered because she could not trust herself to speak. She bent her head so that the sides of her hair swung further and he could not see her face, but a sob shook her, then another. Peter did not go away as ten minutes ago he would have done at once. Instead he felt an answering uncomfortable tightening in his throat and, Thank God, Cecily came in then, thought Peter.

Cecily came in and looked at them, but all she said was, ‘Peter, you had better have some breakfast,’ and, ‘Tracy! Are you letting that bacon burn?’

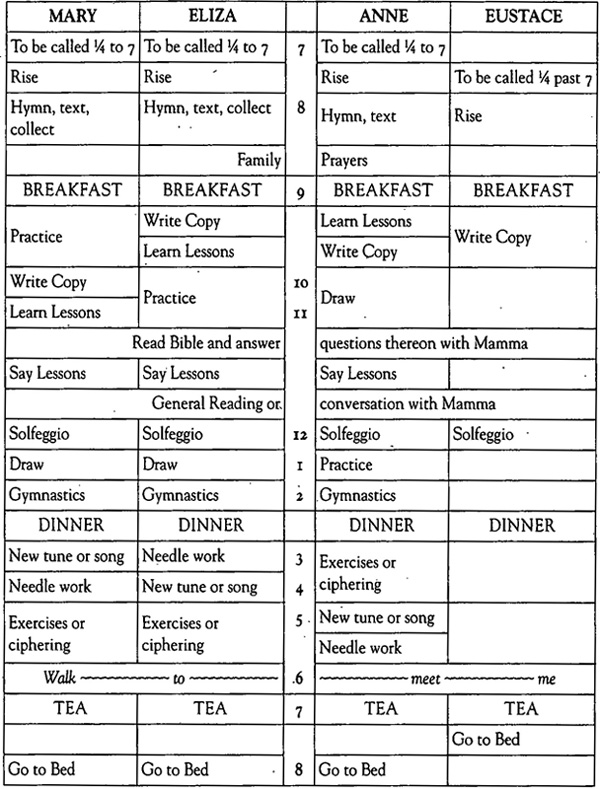

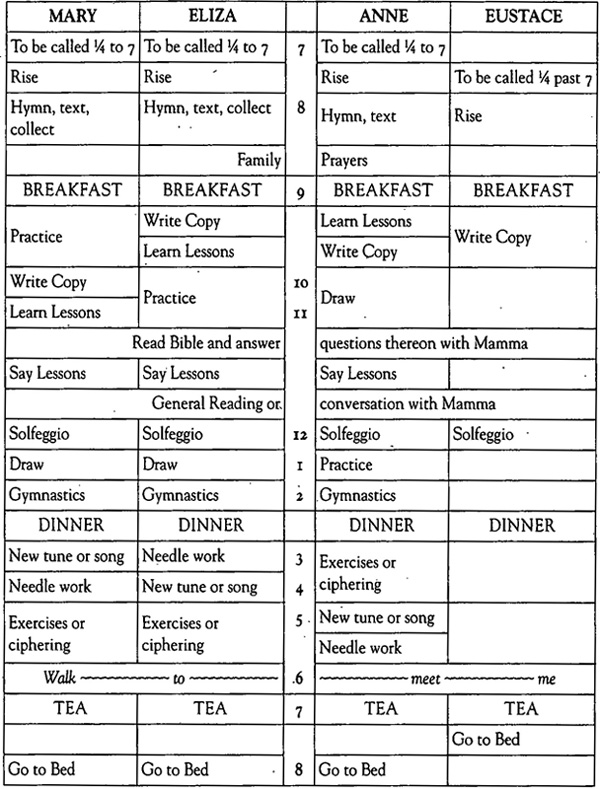

In Eustace’s day, before there can be bacon there have to be family prayers. Mary and Eliza, the two eldest of the Brood, take it in turns to put out the books, ‘if you have learned your hymn verse, text, and Collect,’ says Adza.

‘I have learned them,’ says Eliza. ‘I learned all three while Mary was learning her verse.’

‘Eliza, you must not boast.’

‘But I did.’

‘That will do, Eliza.’

Eliza, at this time, is an exceedingly plain little girl of seven, dressed like Mary in a wide four-tiered skirt of triangular plaid in bilious blues and greens with a white bodice jacket, the vest and sleeves trimmed with white braid. The low neck shows Eliza’s knobbly little shoulders, while her hair is strained tightly back on her head by a round tortoiseshell comb, so that her forehead is revealed as large and unmistakably bumpy, but, ‘Those are my brains,’ says Eliza.

‘Eliza, you must not boast.’

Eustace, who loves them very much, has drawn up a timetable for his children.

Eliza has no inkling yet that he never intends her to get far beyond it: ‘Solfeggio, needlework, drawing, accomplishments,’ mocks the grown-up Eliza, but now there is nothing to disturb her content. At the foot of the nursery stairs, five holland pinafores hang on hooks; only five because Jared is still a baby, and Damaris is not yet born. The pinafores vary only in size; after breakfast the Brood will put them on, boys and girls alike because there is no difference marked between them yet, except that little Eustace, being just five, learns less, while Mcleod the Second, who is two years old, does not learn at all. Eliza can still be proud; she has not yet understood that she is only a girl, plain and without money or distinction – the little Quins are not invited to the St Omer parties, for instance – she only knows she is the best at copying, arithmetic, and reciting, though the younger Anne is gently best at music, while Mary, like Adza herself and, years later, like Bella, has a voice like a flute. Little Eustace is not best at anything; Mcleod the Second does not count. The three girls in their plaid and white, ranged before Adza, have each a private hassock to kneel on, their own prayer books to read from, while the mop-headed little boys have nothing at all and simply stand by their mother.

Abbie sounds the gong – Adza has forgotten she was ever in awe of her – the maids file in; only Cook is excused because she has to get breakfast, and the knife-boy because he is too dirty.

Eustace comes in, solid, almost square in his long buttoned-up frock coat and his fawn waistcoat with lapels that are always slightly crumpled because a child often hangs on to them when riding cockahorse on his knee. He has a chain that ends, as the children know, on one side with a seal and fob and on the other with a large gold watch which they are allowed to hold in their hands when they have a dose of medicine – Gregory powders, thinks Eliza with a shudder, or rhubarb.

Eustace and Adza, at this time, have grown to look very alike; the plump little bride has become solid and by the weight and width of her clothes – fourteen yards make a dress-length for Adza – she is even squarer than her husband, just as her brown hair is a deeper shade than his, her round eyes deeper blue than his pale-blue ones.

As Eustace comes in there is a respectful standing up and a hymn is sung. One of the little girls says the Collect of the week – Eliza loves this – and then there is a rustle as everybody sits for the chapter that Eustace reads from the big Bible carried in by Abbie from the hall. A longer, louder rustle follows, with creaks of whalebone – now and then even a crack – as they all kneel devoutly facing their chairs, while Eustace prays aloud, which makes the young maids inclined to giggle. The little girls kneel on their hassocks, the soles of their small cloth boots upturned to heaven, the ends of their embroidered long drawers showing above a gap of white stocking, and their heads so devoutly bent that their hair falls forward and Eustace can see the napes of their necks, so small and white and vulnerable that sometimes he loses his place.

The smell of bacon drifts across the Lord’s Prayer – always for Eliza, the two are mingled, though she does not, at that age, get any of the bacon – and as the smell rises Eustace increases his pace. Adza deplores this – she knows what the maids must be thinking – but she is too tender-hearted to tell him of it, and it is, thinks Adza, a comforting thought that breakfast is waiting; the children, upstairs, have porridge and milk, white bread and the second-best butter; but for Eustace and Adza the morning-room table is laid with porridge in blue-and-white plates, cream, brown bread, muffins, honey and rolls, while the bacon keeps hot in a silver dish over a flame, with another dish of kidneys or sausages or sometimes kedgeree. A comforting thought, thinks Adza and gives a contented sigh; a good table, a clean and comfortable house, a full nursery; and a thriving business – what more could anyone want?

It is the year of the Great Exhibition. All England is humming with new inventions, new ideas; new horizons too, because foreigners have come from all parts of the world. ‘Those are mandarins!’ squeals Eliza, finding engravings of them in the Illustrated London News, and she asks, ‘Does my great-uncle Mcleod look like that?’

‘Don’t be foolish, my dear. He is not a heathen Chinee!’

Eliza loves to unfold the diagrams and pictures. “‘The Transept looking north,’” she reads out reverently. ‘“The view from Hyde Park East.” “The Pavilion.” “Her Majesty the Queen opening the Exhibition on May the first, eighteen fifty-one.” “The Prince of Wales in Highland dress,”’ Eliza reads out; “‘The Princess Royal in white lace with a wreath of flowers.’” Adza likes to hear about the royal children’s dresses, but Eliza is not interested in them but in herself and cries, ‘Oh, Mamma, when can we go? We are going, Mamma? Say we are.’

‘Papa may go,’ says Adza comfortably. ‘For us it is too far.’

‘But Mamma! We must go!’

‘You may not say “must” to Mamma, Eliza.’

London has never been so fashionable and gay. The small Eliza follows it almost breathlessly. “‘Court and Haut Ton,’” she spells out. ‘What is Haut Ton?’

‘I don’t really know, my dear.’

‘“May tenth. The Queen gave a State Ball at Buckingham Palace to a most brilliant Court.” How lovely,’ breathes Eliza. ‘“Covent Garden, Carlotta Grisi danced in the revived ballet of Les Métamorphoses as the sprite, assuming six different forms with the utmost grace and vivacity.” Who is she, Carlotta Grisi?’

‘I don’t know, my dear.’

‘“Mr Macready’s last performance as Macbeth.” Who is Mr Macready? Can I read Macbeth?’

‘You must ask Papa,’ but it is no use asking Papa either; he doesn’t know or care, ‘about anything,’ cries Eliza. Not about the hummingbirds in Mr Gould’s collection at the Zoological Society’s Gardens in Regent’s Park; nor that it takes only eleven hours now to get to Paris – ‘My dear, I am not likely to go to Paris’ – nor about Mrs Fanny Kemble’s Shakespeare Readings, nor the ascent of Mr Hampton’s balloon. He does not care a pin about any of them.

All the same Eliza loves her father far more than her mother and she finds his work as enthralling as she finds Adza’s domesticity boring. Eliza has never wanted to help give out the stores, or make cowslip wine or jam or pickles, but she loves going to the quarry with Eustace. All the children have been there; it is next door, just up the hill. They have been shown – though Anne grows cold with terror because she knows a bang is coming – how the explosives are placed in the holes drilled in the granite hillside; ‘Ten minutes and that ull blaw up, my dears’; and seen the cutting of the granite while water squirts to prevent its getting too hot. Even the noise of the drilling is exciting to Eliza, when the deadly fine granite dust flies up – ‘It can kill a man if it gets into his lungs’ – and she takes a real delight in the precision and finish of the polishing and letter-cutting and carving of headstones.

She has never been to Canverisk, though Little Eustace has, riding across the moor on the front of Eustace’s saddle, but Eustace has made out a copy about the works for all the children to write and learn: ‘What is china clay? It is a high-grade white or nearly white clay, formed by the natural decomposition of mineral feldspar.’

‘What is this natural process called? This natural process is called kaolization.’

‘For what is china clay or kaolin used? It is used in the manufacture of paper, pottery, ceramics, and pigments.’

Mary complains that the words are too difficult, but Eliza loves them. ‘Pigments, ceramics and pigments,’ she chants. ‘And our china clay, in England, is the best in the world, especially here on the moors. Papa says so,’ she boasts, but now the first buffets of being only a girl begin to be felt. A girl cannot ride cross-legged on the front of Eustace’s saddle; she must stay at home with Mamma, which in Eliza’s case is not comfortable for either of them.

‘Mamma, why does Papa always read prayers? Why not you?’

‘It’s Papa’s place, my dear.’

‘Why is it Papa’s place?’ or, ‘Mamma, does the lady have to wait until the gentleman asks her?’

‘Asks her what, my love?’

‘To marry her or can she ask him first?’

‘Mamma, when we go up to the Exhibition’ – and Eliza still cannot believe they are not to go – ‘shall I call the Queen “Your Majesty” or just plain Victoria?’

It is a cuckoo voice – Adza cannot compete with it – and gentle little Anne when she says ‘no’ can never be made to say ‘yes’ and when Damaris, the youngest, is born and grows up, she is oddly shy, ‘like a little savage,’ says Polly, and will not speak to people or, even at five years old, go into anyone’s house, ‘not even for the nicest party,’ says Adza, unless Polly holds her coat and hat in front of her the whole time so that she can see them and know she can go away. ‘But they were all so sweet,’ says Adza, ‘with their silky heads and their little hands joined together when they prayed; they were so sweet, but where are they now?’

‘Once upon a time,’ she could have said, ‘the house was like a nest.’ Indeed, it is for that Eustace calls his children the Brood, but, ‘Where is everyone?’ asks Eustace, looking around the empty morning room, and Adza echoes, ‘Where are they?’

Some are gone legitimately as it were: Mary marries, ‘the only available man,’ says Eliza. He is Dr Smollett’s new young assistant and, ‘Who would want to marry a man like that, no better than an apothecary?’ says Eliza. Little Eustace dies; Mcleod the Second has been pledged from his birth to go out to China to Great-Uncle Mcleod – Mcleod the Second, who sends home the famille rose. These absences Adza can understand; she can grieve over them, miss these children and mourn their empty places without bewilderment, but the grown-up Eliza will not get up in the mornings and lies in bed staring at the wall and has written ‘fuddy-duddy’ across her prayer book, while Anne has suddenly begun going to the common Bethsaida chapel in the village and, ‘Goodness knows where Damaris is! Probably walking the moors, like a Gypsy, and all alone!’ says Adza. Then Mary ceases to write, Mcleod the Second is in mysterious trouble in China while Jared, the adored, has been sent to this costly and dangerous place, Oxford, and, last time he is home, comes in at breakfast, still in evening clothes, his breath smelling, ‘of spirits,’ says Adza, horrified.

‘Of course it smelled,’ says Jared. ‘I had been drinking.’ He laughs, but to Adza he is still the baby of her sons, the one who makes up to her for Little Eustace, and she cannot bear these signs of – ‘profligacy?’ whispers Adza.

‘Mother, we are not chapel even if Anne is,’ says Eliza. ‘Don’t be narrow-minded.’ But ‘Must they all, always rebel?’ asks Adza; it seems that almost always they must. The morning room feels empty with only Eustace, Adza, and the maids and presently Eustace decides to give up family prayers.

Eliza will not get up because she does not want to get up. ‘What is there to get up for?’ asks Eliza.

Anne is up early to practise before breakfast. Her piano playing – ‘never very good,’ says Eliza – is the solitary accomplishment left of all that Eliza and Anne bring back from school where, at Eliza’s continual ‘worritting’ as Polly calls it, they are sent for a year, to be ‘finished’. ‘Finished, we haven’t started yet!’ says Eliza.

The school is Miss Manners’s School for the Daughters of Gentlemen, at Truro, ‘not even out of the county,’ says Eliza in shame. She knows from village gossip that Helena St Omer, whom she has never met, is being sent to Dresden. Miss Manners’s is distressingly simple and humdrum, its curriculum only an amplification of Eustace’s timetable. In the house, still, are a teapot stand in burnt-poker-work made by Eliza – some of the hollows impatiently burned too deep – and an afternoon tea cloth and dressing-table set embroidered in shadow-stitch by Anne, two sketchbooks covered in linen with a wide band of elastic, and filled with watercolour sketches of the moor, Mother Medlar’s Bay and Penzance. ‘We learned some French, which we shall never speak, the use of the globes, for places we shall never see, and we brought it all home in a portmanteau of pride,’ says Eliza.

She cannot bear to think now, eight years later, of those silly – silly to hope – young creatures, herself and Anne, though it is not easy to know if Anne has any hopes or ambitions. Eliza, when she comes home, has hopes and excitements as swelling and unmentionable as the then rather clumsy breasts behind her new grown-up dresses. The thought of those dresses makes Eliza wince; before she leaves Truro she buys a dress with money that her godmother, Great-Uncle Mcleod’s Mary Bazon, whom she has never seen, sends her for her eighteenth birthday.

It is a ball dress of salmon-pink ‘poult-de-soie,’ as Eliza tells Adza, and it is not crinolined. ‘Crinolines are on their way out,’ says Eliza scornfully. It has the fullness swept around to the back in a pannier, which falls to a train ruched with lace and velvet bows. It makes Eliza’s waist look becomingly slight though the bodice, fashionably low and right off the shoulders, gives her the same knobbly look that she had as a child. With the dress go two stars, mounted on velvet bows, for her hair. ‘Very pretty,’ says Adza doubtfully, ‘but when will you wear it?’

‘The St Omers give balls at Tremellen.’

‘They would hardly be likely to ask us,’ and as Adza looks at the dress, comprehension begins to cloud her china-blue eyes. Mcleod the Second is nearly fifteen, but what good is that to eighteen? and Jared is only a small schoolboy. Dr Smollett has not replaced his young assistant, there is no curate and, Where else are there any young men of our kind? thinks Adza. ‘This is a country place,’ she says slowly. ‘Country and remote.’ The St Omers are often at Tremellen – in fact Jared and Damaris for a while share lessons at the vicar’s with Harry and Helena St Omer, but only lessons, nothing else. The St Omers are often down from London, but there is a firm demarcation. ‘Your father could ask them,’ says Adza doubtfully.

‘It is they who should ask us,’ says Eliza.

Adza does her best. She takes Eliza and Anne to call on old Lady Merron, who is deaf and lives with a companion. They play pool and Pope Joan with the doctor’s wife, the wife of the lawyer in the next village, and with the vicar’s sister, Miss Perry, who has known them all their lives. Anne goes to stay with a school friend in London, with cousins in Bristol, and she has some chapel friends, whom Eliza despises, but she, sharp-tongued and critical Eliza, has never made friends easily and she is asked nowhere. They help one Christmas with a bazaar at St Austell; that is an excitement, ‘but leads to nothing,’ says Eliza. The day when Mr Fitzgibbon, Eustace’s new manager, first comes to midday dinner is an excitement too, but one that speedily fizzles out; he is already middle-aged and, as they learn, he is bringing a wife.

Eustace has installed Mr Fitzgibbon to help him with his expanding businesses, the quarry and the china-clay works. There is much to be done with the integration of two small pits, Canverisk and its neighbour Alex Tor, Eustace’s latest purchase, into one: there are plans for pit development, another pump, new settling pits, a flat floor kiln with the latest hot-air drying, a second warehouse at Fowey. ‘I could do with two Fitzgibbons,’ says Eustace.

‘Why not take me?’ asks Eliza. ‘I could help you, Papa.’

‘You do help me, my dear, by looking after Mamma.’

‘She doesn’t need looking after, and if she did, Anne and Damaris can do that.’

‘You are the eldest now.’

‘Then I should be with you. In the works.’

‘You are a girl, my dear.’

‘And girls can’t learn. They have no brains,’ says Eliza bitterly.

‘My dear, of course they have, only—’

‘They must addle them all day long,’ says a voice.

They are in the office and the voice comes from behind the screen in the corner. It is a shabby old screen hiding the desk where the even shabbier old Jeremy Baxter does his work. Eliza, confronting Eustace at his desk, can just see the old clerk’s wild white hair and every now and then catch a whiff of him, for Jeremy Baxter drinks brandy. Eustace keeps him because, ‘even drunk,’ says Eustace, ‘he’s twice as clever and quick as any clerk in the district.’

‘And twice as cheap,’ says Jeremy Baxter and adds, ‘Quin dearly loves a bargain.’ He persists in calling Eustace ‘Quin’ without the respectful ‘Mister’ and when he has been drinking he can be talkative. ‘Girls are not respectable if they are not addled,’ he says now.

‘But why?’ Eliza cries out.

Jeremy Baxter shrugs. ‘Consuetudo pro lege servatur.’

‘I don’t know what that means,’ says Eliza.

‘Nor does Quin, do you, Quin?’ asks Jeremy Baxter.

Eustace is the most sweet-natured of men, but his rare temper is coming up. ‘I said that will do, Mr Baxter.’

‘But I want to know what it means,’ says Eliza.

‘Consuetudo pro lege servatur? Roughly, “As it is the custom, it must be the law.” At any rate in St Probus. No, there’s no hope for you, Miss Eliza,’ says Jeremy Baxter. ‘No hope at all. You must addle.’

‘But I can learn.’ Eliza’s temper has risen too, though that is not rare. ‘I could do accounts as well as Mr Fitzgibbon, better because I’m quicker.’

‘Which wouldn’t be difficult,’ says Jeremy Baxter.

‘I can give orders and take responsibility. Please, Papa, oh, please!’ but Eliza has not learned to conceal herself; she still clamours and, ‘The men would not like taking orders from a girl,’ says Eustace. He gets up, closing the subject. ‘And you know the works are for Jared.’

‘Who will probably ruin them,’ says Jeremy Baxter.

‘Mr Baxter, you will kindly attend to your ledgers.’

‘Not kindly,’ says Jeremy Baxter, ‘but I will.’

It is of no use Eliza clamouring. Mr Fitzgibbon stays, keeping Jared’s place ready for him while Eliza can arrange the flowers, write notes for Adza, pay calls, visit the cottages, do needlework and sketch, and read all the magazines and novels that come into the house.

‘I shall go to London,’ she says daringly, but London seems impossibly far off and she has no money, no friends. ‘I could be one of those models for painters in Paris,’ she says more daringly still, but she is too thin; those tender young-girl curves have fined down to flatness. ‘I’m ugly,’ says Eliza and no one contradicts her; of all the Brood she is the one to inherit Great-Uncle Mcleod’s long nose, her hair is even more colourless than the others’, and her eyes have a touch of green.

‘You could work for poor people,’ says Anne. ‘That’s what I mean to do.’

‘Like Octavia Hill?’ asks Eliza restlessly.

‘More even than that,’ says Anne, her eyes shining, but Eliza is not listening or looking.

‘Octavia Hill only wants people with money,’ she says which is, of course, not true, but she can hardly give her real reason, which is that she does not want to work for other people, she wants to work for herself. I want to see, touch, feel, she cries, silently, but in a frenzy of frustration, and ‘That eldest girl of Eustace’s,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon to his wife, ‘has the eye of a bolting horse.’

In the summer of 1870 Eliza is twenty-six, Anne twenty-five, Damaris just seventeen. ‘Seventeen has a chance,’ says Eliza and cannot trust herself to think of Damaris.

‘Hate your sister,’ says Polly to Eliza, ‘that’s wicked.’

‘I don’t hate her, I pity her,’ says Eliza loftily, but as usual Polly has divined the truth. There are times when Eliza does hate this younger sister who is so different from herself, so beautiful, unashamedly big and free, and so content.

Damaris and Jared are like two towers among the stocky Quins. Where the others have fine straight mouse hair, excepting Anne who is flaxen, their hair is black and Damaris has falling curls, almost vulgarly abundant. They have the only dark eyes in the family, so dark a blue they are almost black, sloe-shaped and lashed ‘like an ox’s,’ says Eliza. Everything about Damaris is big; when she is laced, in an attempt to give her a waist, her bust swells up almost embarrassingly high and firm. ‘It’s all that walking,’ says Adza in despair. Damaris walks, Polly says, ‘like one of the quarrymen’s wives,’ but it is more like a quarry boy, often barefoot and for miles. It is easy to believe that that faraway sailor must have been a peasant. There is no denying that Jared and Damaris are magnificent creatures, but in small society in the seventies, magnificent girl creatures are not thought polite; Jared is accepted as dashing, but Damaris is unmistakably vulgar and Eliza is sure that the reason why the Quins are not ‘accepted in the county,’ as she says, is not only because Eustace is in trade, and Adza homely, nor because Anne has reverted to chapel like a villager – ‘thank God only the village knows that’ – but because, thinks Eliza, this ignorant young sister makes herself conspicuous traipsing over the whole county and running wild.

Adza has to let Damaris run wild. Away from the moors, she is like a caged animal and, like an animal, makes no protest, only wilts, ‘as if she were dumb,’ says Eliza impatiently; wilts and suffers. When Damaris at fifteen is sent to Miss Manners’s, ‘to be tamed,’ as Eustace says, she accepts it, but she neither eats nor sleeps and becomes so thin and starved that she has to be brought home. It is odd to see her with a blanched sick skin and it frightens Adza. ‘But you shouldn’t have brought her home,’ says Eliza. ‘She can’t go on being a savage forever.’

‘Perhaps she would have grown used to school,’ says Adza, whom anyone can talk into anything, but Damaris says simply, ‘I should have died.’

That August there is a three days’ gale. It brings a lilac dawn with the wind still tearing at the sky. Though the gale is blowing itself out, the morning is dark and full of wind and the butcher boy has to force his way down against it from the village. At China Court the elm branches thresh as if they were going to fall, while up above, the wind howls and whistles past the village, where, they say, the sound of bells is blown out across the moor. It is the wind in the church belfry shaking the bells, something heard only on the roughest of days, ‘and Damaris is out!’ moans Adza.

She comes in long after breakfast. ‘Damaris! You haven’t been up on the moor!’ but Damaris only laughs.

‘You will get coarse and brown,’ says Eliza, but Damaris is, rather, ivory and red; her skirt and the disgraceful old purple cloak she wears are soaked, rain hangs on her hair. ‘You might be a Gypsy,’ scolds Adza.

‘They thought I was,’ says Damaris and laughs again.

‘They? Who?’

‘Harry St Omer and a man.’

When, for that brief while as children, Jared and Damaris share those vicarage lessons with Harry St Omer, they know one another well enough for Christian names before they are separated and the boys sent to school. ‘Harry St Omer and a man,’ says Damaris.

‘Then the St Omers are back?’

‘Yes,’ says Adza. ‘They arrived on Wednesday. Mrs Tremayne told Cook. What man?’ she asks Damaris.

‘Just a man,’ says Damaris. After a moment she adds, ‘An American.’

‘How do you know he was an American?’

‘They spoke to me. I was sitting on a wall to get my breath, and they rode up to me. I suppose they thought it odd to see a woman sitting in the rain.’

‘More than odd, mad,’ says Eliza.

‘They rode up to me and I heard Harry say, ‘Good God! It’s Damaris Quin.’ Then he rode closer and asked if they could help me.’ Damaris bursts out laughing, but even Anne, who never censures anybody, feels ashamed for her. ‘Damaris! They must really have thought it extraordinary!’

‘Yes,’ says Damaris serenely. ‘Then Harry seemed to feel he needed something else to say. He asked when we expected Jared.’

‘What did you tell him?’

‘I said, “Never.”’

‘You needn’t have said that,’ says Eliza slowly. ‘They might have come over. Goodness knows we never see anyone. Then what did they do?’ she asks.

‘They hovered,’ says Damaris. ‘Perhaps they didn’t like to ride away and leave me there. I said I didn’t need any help, that I was walking, and the American asked, “Is it by choice?” I thought he had a twinkle in his eye, rather like Papa and I wasn’t afraid to speak. I said, “By choice,” and then to help them to go, I jumped off the wall and wished them good day and walked away.’

‘What aged man?’ asks Eliza suddenly. ‘You said like Papa.’

‘Oh! an old man,’ says Damaris. There is a pause. ‘Not very old,’ says Damaris uncertainly.

‘It’s love that makes the world go round,’ sings the little kitchen maid as she peels apples for Cook.

There are very many songs in the house, songs and ballads, hymns and nursery rhymes, and most of them are about love. Love, Liebe, amour, amore, in English, German, French, and Italian. Outside the drawing-room window on summer evenings when the white rhododendrons are out, the lamplight falls on the exquisite full-skirted flowers bunched on the dark-green leaves. At sunset, between the light from the windows and the light from the sky, they hold a mysterious pink fire. Inside the windows there is firelight as well as lamplight – even on summer evenings the big room is chilly. There are green coffee cups with silver edges and the Schubert song falls sweetly as honey – ‘Röslein, Röslein, Röslein roth, Röslein auf der Heide,’ the young woman in the draped dress sings, cascades of lace falling from her sleeves as she lifts her hands.

The young woman’s name is forgotten, but the song is still in the house, as is the moment when Lady Patrick catches sight of her husband’s face, not listening to the song, but watching the singer with an eagerness that Lady Patrick knows. The eagerness is tempered for the moment by politeness, but Lady Patrick knows what will come later. She turns her head away and looks into the fire, not to hide tears – she has no tears left now – but because an old wound throbs as it feels the cold.

Love. ‘Parlez moi d’amour,’ sings Bella. Even as a woman nearly thirty she has the fluting voice of a boy, and McWhirter, the fierce bachelor gardener, is equally contradictory – he who hates women sings as naturally as he breathes: ‘She is coming, my dove, my dear,’ and, ‘My love is like a red, red rose.’

The Lieder are in Lady Patrick’s time, but in Mrs Quin’s and John Henry’s, music is still brought to dinner parties and left in the hall, or upon the spare-room beds with the wraps, to be modestly fetched after dinner. Stace and Bella and the Three Little Graces sit hidden at the top of the stairs listening to: ‘I passed by your window’, ‘The Rosary’, and ‘Because’. ‘Because God made thee mine,’ thunders the baritone, ‘I’ll cherish theeee,’ which gives the girls sentimental shivers up their spines.

‘Trink, trink, Brüderlein trink,’ sings Minna as she sits at her mending, or ‘Ach du lieber Augustin.’ She is to suffer for her German in the 1914–18 war; none of the St Probus villagers then know the difference between German and German Swiss, but now she sings blithely. She knows that Groundsel makes it his business to rake the path below the kitchen window because of her singing. Raking up the old dead leaves from the elm trees, he pauses and looks at the window as if he would like to see inside, and the look on his dark face is thoughtful and gentle.

Effie, the impertinent little kitchen maid in Minna’s time – Cecily has then just been promoted to under-housemaid – Effie leans across Minna, plucks the thimble off Minna’s hand, and taps on the window with it. That seems an unpardonable liberty. Minna cannot bear it that her thimble should tap to Groundsel in that forward way and immediately she stops singing.

Songs are memories, ‘even when you don’t want them to be,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘They persist,’ she says in pain, and once she is betrayed into crying out to Bella, who has a passion for old tunes, ‘Don’t play that. Don’t.’

Bella can never accept a request without knowing the reason and, ‘Why not?’ asks Bella, playing on. ‘It’s from some old thing called Floradora.’

‘I know.’

‘Then why do you mind?’

‘It hurts,’ but Mrs Quin does not say that to Bella or anyone else. ‘It sears’ would be nearer the truth; each time Bella plays this tune, the silly lilting tune – ‘If you’re in love with somebody, Happy and lucky somebody …’ – she hears it again, not tinkled out on the piano or sung, but played by a band, ‘Yes, here at China Court a band, a dance when …’ but Mrs Quin refuses to think of it.

There are war songs that wound too: ‘Sergeant of the Line’ and ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’ in the Boer War. Borowis is killed at Paardeberg, ‘but for me he had already gone,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary’ is played by a brass band as she watches John Henry marching away with his draft on the way to France; ‘There’s a Long, Long Trail’ and ‘Little Grey Home in the West’ belong to that time too and in 1939 there is another band playing ‘Roll Out the Barrel …’ with again the beginning of dread, this time for Stace.

Why is there so little of Stace in the house? Mrs Quin’s heart has always cried that. Why? ‘Because he was hardly ever here,’ she says. ‘He was always away.’ Is it John Henry’s doing, or is it simply the pattern of a little boy of that time, of that kind? She never knows, but when she tries to think of Stace, remember him, John Henry is always in the way. Perhaps that is her punishment. Then does John Henry know? He never says and she never asks him, dares not ask, though she has always been able to say anything to John Henry; but it is he who, six months after Stace is born, plans the trip to Cape Town and Johannesburg to see the mines – St Probus is a mining village – and Stace is handed over to trained starched McCann. ‘You will visit the nursery once a day, ma’am, and that at my time,’ and the round-headed rosy baby disappears. He comes back for a year or two as the enchanting small boy in the portrait in her room, but in a moment, it seems to Mrs Quin, there is school, the dreadful system that snatches little boys away from their mothers and turns them into bony objectionable small monsters. ‘But you must not show feeling,’ says Mrs Quin, ‘not even if he is unhappy at school, nor when public school takes him and changes him completely.’ She tries to be scrupulously fair; the girls are given as much as or more than Stace. Remembering Eliza, Mrs Quin insists that they go to boarding schools, and finishing schools abroad, are trained, and have coming-out dances, yet there is no mistaking where her heart is. ‘But what is the use of having a heart?’ she would have asked; for Stace, after school there is Sandhurst, then the army, then marriage, then death. He is killed on the beach at Anzio in 1944.

Sometimes, in February, come rare days warm and still enough for April, when primroses, celandines, and crocuses that have bent to batterings of rain and sleet stand up in shining and confident colours. The garden is full of birds, the first bees find the catkins and palm buds swell; Mrs Quin is out all day, nor will she lose time by coming in so that Cecily follows her around with a tray. ‘I can’t stop,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘At this time of year it will be dark by five o’clock.’

‘Nine hours’ gardening is too much at your age,’ says Cecily unmoved. ‘Sit down and eat,’ but on this February Tuesday of 1944, Cecily is away for the day and Mrs Quin has been gardening unchecked when, in the afternoon, she looks up from the clump of Japanese anemone shoots she is weeding and sees the vicar and Mr Throckmorton, the schoolmaster, walking up the drive.

The combination of vicar and schoolmaster tells her at once and without words what they have come to bring her. In the village they would know she is alone and the postmaster would not send a telegram like that by the postman or a boy. She would have preferred it to come as usual. ‘The envelope would have been enough,’ says Mrs Quin.

For a moment she stays where she is, and slowly picks a snowdrop from where it has seeded itself among the stems of the young anemones. She has plenty of snowdrops picked already for there are hundreds out in the dell; she has put a bowl of them in the morning room, but she picks this solitary one now and smells it, her fingers trembling; it smells, very faintly, of honey, but more of cold wet earth and holly, from the old leaves that have blown over the clump.

Then she stands up. Her knees are stiff with kneeling in the cold, and, as Cecily has warned her often enough, rheumatic pains have started in them. Her tweed skirt bulges at the knees and she is wearing her disgraceful old jerkin – Bella says it is not fit to be seen – two scarves, woollen stockings, and leather boots caked with mud, while her old gardening gloves are two sizes too big. ‘Proper o’ scarecraw,’ Groundsel would have said, but Groundsel is not there that afternoon either; he is on Home Guard duty. No one familiar is near her and, quite alone, she waits for the vicar and Mr Throckmorton to come up to her; she feels wisps of hair blowing across her face and cold gripping her heart.

As they tell her, she fixes her eyes on the snowdrop, minutely looking at the three green-edged petals, the tiny stamens. It is the schoolmaster who speaks; the vicar is the new young man she has not met yet and obviously it is only a sense of duty that has brought him. Well, duty can be very kind, thinks Mrs Quin. As the words are spoken, though she is expecting them, the snowdrop seems to burn itself into her brain. The pain is so intense that she has to close her eyes against it, but it burns through the lids. Stace! She gives a strange little gasp and the young vicar puts his hand on her arm.

Mrs Quin opens her eyes. The snowdrop has gone; she has dropped it; there is only the sun-filled day and the two faces regarding her anxiously. ‘Thank you,’ says Mrs Quin politely, and because it is afternoon she asks, ‘Will you stay and have some tea?’

The faces look shocked. It is the young vicar who recovers first. ‘It is we who should make tea for you. Or perhaps you would like a little brandy.’

Mrs Quin is silent while they watch her; then she says abruptly – the vicar does not know yet that it is her way – ‘In that case I had better go on gardening.’

She does not know how long they stay after that. She has no inkling that she has been unconventional, perhaps even ungrateful and rude; she simply gardens on, carefully freeing the suffocated anemones, clearing away the dead prickly leaves, snipping dead stems, picking out stones, which are always a nuisance in the China Court garden. She does not feel it when the sun goes down, though the garden grows very cold, and Sophonisba – the spaniel before Bumble – noses her to go in; Sophonisba likes her comforts, but Mrs Quin takes no notice. At times the snowdrop comes back, and Mr Throckmorton’s words; she can feel them beating in her head.

Cecily finds her when it is almost dark. Without a word, she takes away the gardening fork and helps Mrs Quin to her feet, when her knees hurt so agonizingly that she cries out. Cecily helps her to the house and takes off her boots and gloves; and presently, when the fire is making its full noise in the kitchen, Mrs Quin has tea, laced with brandy.

Afterward Cecily puts her to bed; she offers no sympathy; her face is as grim as Mrs Quin’s and they hardly talk, only, as Cecily brings the old stone hot-water bottle wrapped in flannel to put against Mrs Quin’s ice-cold feet, ‘I don’t have a bottle,’ says Mrs Quin.

‘You will have one tonight,’ says Cecily and before she leaves the room she comes and stands by the bed. ‘I think you should ask Mrs Barbara to send you the child,’ says Cecily.

It happens to suit Barbara well; she has been offered her first real part in a picture, ‘How did she get that?’ asks Walter. ‘I can guess how,’ says Bella. The picture is to be made in Mexico and Tracy is getting too big to trundle around, and thin, nervous, and shamefully backward at her lessons. Tracy is sent over to China Court, ‘and to stay,’ says Mrs Quin, but the picture is disappointing – ‘Disappointing! A disaster,’ says Bella – Barbara gets no more parts, and decides to marry again and wants Tracy back and, ‘That was the third time I was stricken,’ says Mrs Quin.

‘Memory is the only friend of grief’ – Alice, the village girl who comes as maid-companion to Tracy, writes that on one of the tombstones she designs. Alice likes to draw tombstones for all the people she knows and Tracy colours them from her paint-box. ‘Memory is the only friend of grief,’ writes Alice. Tracy shows it to Mrs Quin, who says it is not true.

Even when one is stricken, much remains – often creature things: drinking good tea from a thin porcelain cup; hot baths; the smell of a wood fire; the warmth of firelight and candlelight. The sound of a stream can be consolation, thinks Mrs Quin, or the shape of a tree; even stricken, she can enjoy those. To hold a skeleton leaf, see its structure, can safely lift one away from grief for a moment, marvelling; and sunrises help, she thinks, though sunsets are dangerous, and moon and stars; they stir too much. Shells are safe, and birds and most little animals, kittens or foals especially, for they are not sentimental. Dogs sometimes know too much, though it is then, after Tracy, that she gets a new puppy, Bumble. ‘I have been happy in food,’ Mrs Quin is able to say. How ridiculous to find consolation in food, but it is true, and when one is taking those first steps back, bruised and wounded, one can read certain books: Hans Christian Andersen, and the Psalms, Jane Austen, a few other novels. Helped by those things, life reasserts itself, as it must, even when one knows one will be stricken again: Tracy, Stace, Borowis, those are her private deepest names.

‘But what was Borowis like?’ asks Tracy in one of her many times of asking.

‘His hair was cut round in what they called a pudding-basin cut,’ says Mrs Quin one day, but it cannot have been; Borowis is thirteen when she first sees him and boys of thirteen do not have their hair cut like that. It must be the ‘Boy with the Hoop’ in the Benjamin West – one of Lady Patrick’s family pictures – who has that pudding-basin cut, but Borowis? It is strange that Mrs Quin cannot remember, although she can describe every line of John Henry, from the pale slow heavy little boy to the pale slow heavy young man, ‘unfailingly kind and steadfast, once he had made up his mind,’ says Mrs Quin.

John Henry does not make it up quickly, not even as a small boy. Soon after they know her, Ripsie begs to be allowed to say she lives at China Court. ‘You can’t, because you don’t,’ says John Henry.

‘She can if she wants.’ Borowis is grandly generous.

‘Want or not, Mother would never allow it.’

It is odd that it is John Henry, not Borowis, who has to fight that particular battle.

‘But Borowis was the eldest. He should have had China Court,’ objects Barbara in her short time with Mrs Quin.

‘The eldest – technically.’ As soon as she has said that Mrs Quin knows it is not the right word and sure enough Barbara pounces.

‘What do you mean, technically?’

‘He never grew up,’ says Mrs Quin groping, and then, suddenly, she can exactly describe him. ‘He stayed young and cruel.’

‘You loved him,’ says Barbara at once.

Mrs Quin looks up and sees that Barbara’s eyes are filled with pity and – liking? asks Mrs Quin surprised. Perhaps not liking but kinship; in this moment they are not the daughter-in-law who has wounded the son, the mother-in-law who sits in judgment, but two women who have loved and know how to love.

‘You loved him, yet you married John Henry.’

‘Yes,’ says Mrs Quin and she adds in justification, ‘John Henry had the house.’

‘I think that’s sad,’ says Barbara.

‘Sad and glad,’ says Mrs Quin.

How can something be sad and glad at the same time? For most of the Quin women, it has been like that. ‘All unhappiness,’ says Mrs Quin, ‘as you live with it, becomes shot through with happiness; it cannot help it; and all happiness, I suppose, is shot through with unhappiness. But I was usually happy,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘I had Stace and the garden. There were times when I didn’t remember Borowis for years.’

Adza is happy because it never occurs to her to be anything else, though she is troubled by the strange egretlike children that she has produced – not swans, egrets, those outlandish birds with the coveted feathers. Perhaps Adza is obtuse; it certainly never occurs to her that Eliza is sharp-tongued and restless because she is bitterly unhappy, but then Adza has never been bitter in her life.

Eliza, in the end, finds happiness of a peculiar, but to her, satisfactory, kind. No one knows what Anne finds, for Anne is always the same until she springs her surprise: to the end she is quiet and withdrawn as a shadow, if a shadow can be pale gold. Damaris is not happy at China Court, she is blissful. Jared, her dark brother, marries the happy young Lady Patrick and makes her unhappiest of all.

It is Mr Fitzgibbon who sees the first signs. On the young couple’s first morning at China Court, Jared takes Lady Patrick to look over the quarry, ‘and believe me, I have never seen anyone as lovely,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon. It is beauty that no one can deny, as they cannot deny beauty to a tree in blossom, or to an April sky or a pearl. ‘Yes, a beautiful woman,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon. ‘Now I have seen her I know I have never seen another,’ and, ‘No wonder her father was furious.’

Beside her Jared’s good looks seem flamboyant. ‘Well, she is another clay,’ as he says himself when he is penitent.

‘An earl’s daughter?’ asks Adza when Jared’s first letter comes. ‘How can Jared marry her?’

‘An Irish earl,’ says Eustace, trying to keep his head level, but this is not the sort of Irishness Eustace, and most other Englishmen, think they know.

Jared pretends he knows. ‘My little Patrick,’ says Jared introducing her. He has called her that from the beginning and the name sticks. He thinks it is amusing; her family does not. ‘Arragh! They are a feckless lot, these Patricks,’ says Jared in what he thinks is Irish speech, whereas the Clonferts – the Clonferts of Clonfert and Brandan Abbey, Brandan with an a, not an o – are as aloof and rigidly cold as they are rich. ‘Narrow and noble,’ says Harry St Omer. ‘And we do not say, “Arragh,”’ they might have said, but Jared persists in saying they do. He is almost as obtuse as Adza. ‘Why did she marry Jared?’ asks Eliza, amazed.

Jared has only to look in the glass to know the reason why. He is the youngest son and, after little Eustace dies and Mcleod the Second goes to China, the only son at China Court and he is quite amazingly spoiled. He goes to Rugby with Harry St Omer, then to Oxford, where he is ‘very well breeched,’ says Jared, not in Lady Patrick’s sense of the words, which means estates, even half a county, very well breeched for China Court. ‘But an earl’s daughter!’ says Adza dazed.

She does not live to see it, and Eustace has had a stroke and handed over the quarry and works to his son before she comes, because Jared has to wait for his Lady Patrick to grow up; she is still only eighteen when she runs away with him. They are married before her father and family can stop them.

‘But they will forgive me.’ She is so happy and confident that she is sure no one can resist her. No one, ‘But they did, damn them!’ says Jared.

They write and the unkindness of those letters still stings the air. ‘You have married out of your kind and out of your faith. I do not think you can come here again …’

‘You have put one of God’s creatures before God.’

‘You have chosen your bed. You need not ask us to help you out of it.’

And Lady Patrick’s quivering pride writes back:

‘We shall never come.’

‘I love him better than I love God.’

‘I like my bed.’

They are young phrases but she is very young. All the younger and fresher, thinks Mr Fitzgibbon, almost naïve because she has been cloistered and strictly kept. She is as unspoiled as her complexion. ‘Like a rose,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon, who over Lady Patrick is unashamedly sentimental. ‘Like a wild rose.’ Mrs Quin says that too.

In the summer of 1920, a mouse dies behind the wardrobe in her and John Henry’s bedroom. The weather is so hot that Sam Quin from the village – a village Quin – has to be sent for at once to unscrew the big cupboard with its bevelled looking glasses and flowered china drawer knobs. ‘A fancy piece,’ says Sam.

It is fancy. Fresh from Dublin and London, Lady Patrick turns out the bedroom furniture of which Adza is so proud and brings in the luxurious French bed with its brass love knots and wreaths, the gilt-legged chairs with their damask in blue and old rose, the wallpaper striped with tiny roses – peeling now – the grey carpet and white rugs, that match the white curtains embroidered with ferns. The French furniture does not suit the room, nor the house, but it is pretty, the whole room inviting, especially the bed as Lady Patrick first has it, with a pale-blue satin quilt and white muslin pillowcases. Mrs Quin has a honeycomb counterpane and a Paisley shawl.

There is a narrow space between the cupboard and the wall behind it, not much more than a crack. Stace, as a little boy, pushes marbles into it and cannot get them back. Now Sam finds the marbles and a picture. He dusts it and brings it to Mrs Quin.

‘Who is it?’ asks Mrs Quin. John Henry looks, uncertainly at first, then more certainly, and, ‘It must be Mother,’ he says.

‘Your mother? Lady Patrick? Did Lady Patrick look like that?’ and Mrs Quin remembers the hard face, the eyes that were icily unfriendly, the mouth that could say such unkind things, even to a little girl. ‘That brat is not to come into the front of the house.’ ‘Who said you could play here?’ and, pointing a whip to the groom, ‘Mason, put that child outside the gate.’ Mrs Quin looks at the delicate painting in the gilt frame and it is then that she says what Mr Fitzgibbon says, ‘But she’s like a wild rose.’

The picture is pushed out of sight behind the wardrobe. ‘I wonder why,’ says John Henry. ‘She didn’t sleep here. The Porch Room was hers. Ever since I can remember.’

‘Then what happened?’ asks Mrs Quin. She never knows; it is before Ripsie is born.

‘Even on that first morning,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon, ‘only a day back from their honeymoon, as they were talking to me …’

Mr Fitzgibbon meets them on the drive. Lady Patrick holds Jared’s arm; it is as if she does not want to let him go, even for a second. Her dress, Mr Fitzgibbon remembers, is olive-green, faintly barred with pink; her head, and here he is a little shocked, is bare; she is only walking up to the quarry but no other China Court lady would go out of the house without a bonnet or hat. To make up for this she has a ridiculous rose-coloured parasol, ‘the size of a postage stamp,’ he teases in the privileged way of an old family manager, and all the time he cannot help seeing the way her hand tightens, loosens, tightens on Jared’s arm; the little movement is such a private caress that Mr Fitzgibbon turns away his eyes.

‘You have him under control, my lady.’

‘Oh no! Not at all! He behaves monstrously!’ Her face is so radiant that Mr Fitzgibbon feels he ought not to look at it in case he intrudes; then, just at that moment, little Dorothy Gann from the village comes down the lane on her way to the laundry or the kitchen; there is not a girl in the village more slatternly than dirty little Dorothy Gann, but as she scurries past them and down the back drive, Mr Fitzgibbon sees Jared’s eyes look after her. ‘Look, and with interest, damned if he didn’t,’ says Mr Fitzgibbon. He has an insane desire to knock his handsome young employer down.

‘You are staying in Rome,’ said Peter to Tracy as they were finishing breakfast. Warmed and fed he was beginning to feel ashamed of his defensiveness. ‘It must be a wonderful place. What do you do there?’

‘Study.’ Tracy was noncommittal, but Peter persisted.

‘Studying what?’ And I’m curious, he thought, surprised. That was something he had vowed he would never be again.

‘At college I was supposed to be clever,’ said Tracy as if that were deplorable. ‘I won a grant.’

‘But wasn’t that something rather splendid?’ asked Peter puzzled.

‘Yes,’ said Tracy forlornly.

‘Most girls would give their eyes …’

‘Yes, but for me it—’ She broke off. Then, ‘I didn’t know how not to take it,’ she said.

Peter laughed. ‘Was it so very dreadful?’

‘I had to write and research on literary women travellers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, women like Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley.’ She seemed more than ever forlorn.

‘And you didn’t like that?’

‘I don’t know.’ Tracy was evasive then suddenly lucid. ‘They seemed nothing to do with me,’ she said. ‘I wanted something that was mine. I don’t like living in books. I like living,’ she said. ‘Cooking and doing the flowers and having animals.’ She slid her arm around August’s neck where the big poodle sat beside her. He had attached himself to her almost since Groundsel brought him down. ‘I expect it’s hopelessly ordinary, but I like arranging things and being responsible. There are other girls like me,’ she said as if she were arguing defiantly.

‘Not many nowadays.’ And Peter said, ‘I should have thought your mother would have moved heaven and earth to keep you at home,’ but Tracy shook her head.

‘People of her age always want you to do things. Besides, we haven’t a home, only an apartment. An apartment can be a home, but it isn’t.’ She broke off again. ‘You have a farm. That’s a real way to live, but we’ – and she drew the checked pattern of the tablecloth with her finger.

‘When Gran’s letter came,’ she went on slowly, ‘I thought I would stay here at China Court with her, as I used to, but for always. I guess I was thinking of myself, not of her. I had forgotten she was so old.’ She stared at the tablecloth. ‘Well’ – she gave a little shrug and straightened her shoulders – ‘I must just go back to Rome.’

Tracy went through the house. ‘If I were blindfold,’ she told Cecily, ‘I think I should remember my way.’ For years after Barbara takes her away, Tracy shuts her eyes in bed every night and pretends she is going about China Court, upstairs and downstairs, and out in the garden where she has romped with the lemon-and-white-spangled Sophonisba – ‘Before you, Bumble,’ said Tracy now, patting his fatness – pretending she is back in the house with her grandmother and Cecily and Alice, or out in the garden with Groundsel. ‘Is Groundsel still here?’ she asked Cecily, and ‘He is!’ she cried when she found his pasty on the sill.

‘But only three days a week,’ said Cecily. ‘Mrs Quin had to let the garden go – almost.’ That almost was visible in the rose trees pruned, delphiniums staked, beds weeded. There were no clipped edges to the grass now, few trimmed hedges, but there were compost heaps carefully made, tools taken care of, boxes of fresh seedlings. Tracy went out, and, with August racing backward and forward in front of her, Bumble trundling behind, wandered up the paths and came on an old basket put down beside a half-weeded bed, and holding a trowel, fork, and Mrs Quin’s gardening gloves. The trowel still had earth clinging to it; Tracy knocked a little of it off and crumbled it in her fingers.

‘Mother killed herself in that garden,’ Bella was to say and if Mrs Quin could have answered, ‘That’s what I should have chosen to do,’ she would have said.

On the day that Lady Patrick dies Mrs Quin comes out on the terrace and takes a deep breath. For five years she has lived in the love of John Henry, but also in the dislike of his mother; still, in Lady Patrick’s eye, is the defiance of Ripsie’s scarlet tam-o’-shanter, mysteriously an echo of the intrusion of Ann Sly. From the beginning Ripsie is an intruder to Lady Patrick.

‘Who said you could play here?’

‘Borowis.’

‘Who asked you to come inside?’

‘Borowis.’

Ripsie does not mean it to sound impertinent, but it does. Lady Patrick can forget nothing, and even after John Henry has married Ripsie, dreads and dislikes her. ‘Now you will be able to alter everything,’ she says to her when she knows she is dying, and Mrs Quin is glad she finds the grace to reply, ‘Only in the garden. I shall touch nothing in the house.’ She keeps her word. The house is as it was, but she begins on the garden that very day.

‘The gravel must be moved.’

‘The gravel?’

‘Yes.’

‘But it has always been there,’ says John Henry.

‘Not always,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘There is good earth underneath – and granite,’ she says, her eyes lighting up.

‘It will cost pounds.’

Mrs Quin does not say he must give her pounds, though she can guess that many, many pounds must be coaxed out of John Henry. ‘All the money is spent on the garden and the girls,’ Stace says often and teases, ‘The girls to get rid of, the garden to keep.’ Even then Mrs Quin is wise in the handling of John Henry. The beds must be moved – not moved, wiped out, she thinks, and these garish flowers burned, and I shall take down the flagpole, but, with her hand on his arm, she says none of that aloud; she tactfully begins with the gravel.

‘McWhirter will never consent,’ says John Henry, thinking of the bad-tempered Scottish head gardener, and she drops another bombshell. ‘McWhirter must go.’

John Henry is incapable of saying ‘no’ – ‘fortunately for China Court,’ says Mrs Quin. Over and over again in his married life with her he begins by saying, ‘It’s impossible,’ only to find he has done the impossible thing. Mrs Quin as a girl and a young woman is not exactly pretty, but she is ‘like no one else,’ says John Henry. Borowis is more apt than he knows when he calls her a little blackberry girl; she is not a flower, as most girls are said to be, but unmistakably a bramble; as an old woman she grows prickly and harsh. The Cornish believe in fairies and Ripsie might easily be a changeling she is so small, her skin as white as if she has ‘green blood,’ teases Borowis, though her lips are red of themselves – ‘We had no lipsticks then,’ says Mrs Quin. Her eyes have always been compelling and they are greenish too, with dark lashes. Now she looks up at John Henry; though he is not tall, her smallness makes him feel that he is and, though she is now more than well looked after – ‘cherished,’ he could have said – for him she always has the waif look that tears his heart, and he knows he is undone.

‘McWhirter? Why all these changes suddenly?’ he asks, but feebly.

‘It isn’t suddenly,’ says Mrs Quin.

Long ago, when Mrs Quin is Ripsie, Lady Patrick sees the flash of the tam-o’-shanter and catches Ripsie in the garden where, as it is term time, she has no business to be. Lady Patrick comes right up to her before Ripsie looks up; even then her eyes are unrecognizing, vacant, as if she were somewhere – or someone – else. ‘What are you thinking about?’ asks Lady Patrick, curious in spite of herself.

‘Thinking how I should do it,’ says Ripsie.

‘But how did you know about gardens?’ Barbara asks Mrs Quin. ‘How did you begin?’

Mrs Quin has to look a long way back before she answers, even beyond that day with Lady Patrick. ‘It began with the grotto,’ she says, but she could more truthfully have said, ‘It began with loneliness.’

‘I had to have something,’ says Mrs Quin.

When the boys have gone to school, Ripsie is a small solitary again and has nothing to do or think about. ‘It’s odd, the garden has always rescued me,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘In times when I didn’t want to think, or could not bear to, in any emptiness, there was always the garden. But it began with the grotto,’ she says.

The grotto is built by Lily, niece of the China Court cook in Lady Patrick’s time. Lily has graciously been allowed to come from London to spend a month in the country. She is an unappetizing little girl, even thinner than Ripsie, with sharp elbows and the curiously bleached skin of the London poor; Ripsie avoids her until one day, on the drive, she sees Lily making a curious little erection.

It is made of shells, grey-yellow and fluted, and is being built on a bed of ferns that Lily is edging with pebbles picked out of the gravel. ‘What is it?’ asks Ripsie.

‘A grotter,’ says Lily.

‘A – a grotter?’

‘Yus.’

‘What do you do with it?’

‘Git coppers,’ says Lily tersely.

‘Coppers?’

‘Pennies, stoopid.’

Lily does not talk much, she works, ‘fer sumpin,’ says Lily, which means for money, but she enlightens Ripsie a little more because she wants Ripsie to help her. ‘Every year, twenty-fifth ’f July, we mikes grotters – on the pivement, see? Mike ’em pretty, see, and we gits coppers – sime as Guy Fawkes, see.’

‘The twenty-fifth of July? Why?’

Lily has never heard of Saint James the Great, nor seen a statue or a painting of him carrying his palmer’s shell; she does not know why.

Ripsie watches her fitting the shells into place. ‘Let me help,’ begs Ripsie, as Lily means her to do.

They work all morning and Ripsie discovers she is better at this than Lily. She does not throw the ferns down carelessly, or mass them, but plants each one, letting every frond show, and sets them off with scarlet pimpernels, lady’s-slippers, and clover. ‘Yer aren’t ’alf fussy,’ says Lily.

‘Yes,’ says Ripsie contentedly and goes on working.

It is almost finished when Lady Patrick comes home on Reynard, her big chestnut hunter.

Ripsie, wary, would have chosen a more private place than the drive for the grotto, but Lily is adamant. ‘Must be where there’s people.’

‘Why?’

‘So’s they kin see it. It’s fer pennies, stoopid,’ but Ripsie cannot get it into her head that they are building the grotto for money; by now she is building it for love.

Lady Patrick, coming in at the gate, is not in a good temper, and, though she wants Reynard to walk, she gives him a cut with her whip that makes him plunge. Her face, from anger and the moor wind, looks even more ravaged than usual and Ripsie, experienced, immediately makes herself small and silent, but Lily with cockney aplomb, dances up to Lady Patrick and pipes, ‘Penny f’r the grotter, milady. Penny f’r the grotter.’

‘Why are you children playing here?’ asks Lady Patrick and reins the snorting Reynard in so that he plunges still more. ‘Stand, damn you!’ she shouts. Then she says, ignoring Ripsie and speaking to Lily, ‘If I see you here again I shall speak to Cook,’ and swivels Reynard around so that his hind hoofs catch the grotto, scattering the shells and sending ferns and flowers flying. ‘Clear that mess away at once,’ calls Lady Patrick to a garden boy and she rides on up to the house.

Lily puts out her tongue and dances off to the kitchen, but Ripsie has an odd feeling that the small smashed grotto is bleeding, and before the garden boy can move, she has swept it up in her coat, ‘You are not to touch it,’ she cries.

Next day she builds another grotto, by the waterfall where nobody can see it, and then another, bigger and better, but with fewer shells, more flowers, ‘and the grotto grew into the garden,’ says Mrs Quin.

‘Whoever planned this one was clever,’ says Barbara.

‘I planned it,’ says Mrs Quin.

‘Then it hasn’t always been here?’

‘Always,’ says Mrs Quin firmly. ‘This garden was implicit in the house, that other was imposed.’

McWhirter is dismissed, a new young gardener comes and he and later Groundsel help to make the garden. ‘A garden not dictated,’ says Mrs Quin, ‘but growing out of the land itself, with its own contours,’ not seen all in a moment but a place to explore, and a place not only of flowers but of shape and shades, beauty of foliage, of green and water.

There are, of course, failures, ‘downright refusals,’ says Mrs Quin as with, for instance, gentians. ‘Four pounds ten shillings, and not a single flower to show for it,’ explodes John Henry. It is money spent, John Henry protests, ‘for nothing’ but, ‘Not for nothing,’ says Mrs Quin. ‘To learn.’ And she says, ‘You must remember garden catalogues are as big liars as house agents,’ but fifty years of learning does produce ‘something,’ says Mrs Quin.

At the beginning of spring, in the garden, the flowers are pale, the blossom white, some of it so fragile as to be almost colourless; there are snowdrops, primroses, the first pale daffodils, narcissi. Then the yellow deepens with drifts of daffodils along the drive edges while the tops of the old stone walls are thick with celandines. In May, the real colours come: the strong-coloured bluebells and campions in the wood and lanes; gorse among the bracken; buttercups in the fields; and in the garden the brilliance of tulips, primulas, pink apple-blossom buds, and the richness of lilac and irises that have ‘as many colours as a peacock’s tail,’ quotes Mrs Quin. It is strange that the irises flourish where the gentians refuse – but they do, though this is a peat garden. Every May on the sloping lawn where the flagstaff has been azaleas flame higher than her head, apricot, pink, and orange, reflecting through the windows onto the walls of the drawing room inside.

In summer the beds are like the flowered stuffs sold in shops, blue, white, and pink. The garden is filled with the scent of lilies that sometimes wins against the clove smell of the pinks, and at night there is the scent of stocks and white tobacco flowers. In late July, the great bushes of hydrangeas, blue and purple, have heads as big as dinner plates and sway across the drive if they are heavy with rain.

Then the mixture of the borders takes a richer colour, with marigolds, begonias, and phlox of the red that is found in velvet and stained-glass windows; there are marguerites, high stacks of white flowers, taking the light as the sun moves around.