CHAPTER

7

Decipher Old Cooking Terms

As you discover old recipes, you may notice they either lack measurements for the ingredients or they employ measuring standards no longer used. You also might find unfamiliar cooking terms. This chapter contains a glossary of cooking terms from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by Fannie Farmer published in 1896. You’ll also find a chart to help you translate or convert some old measurement standards.

COOKING TERMS

Accolade de perdreaux. Brace of partridge.

Agneau. Lamb.

Agra dolce (sour sweet). An Italian sauce served with meat.

À la, au, aux. With or dressed in a certain style.

Allemande (à la). In German style.

Ambrosia. Food for the gods. Often applied to a fruit salad.

Américaine (à l’). In American style.

Ancienne (à l’). In old style.

Angelica. A plant, the stalks of which are preserved and used for decorating moulds.

Asperge. Asparagus.

Au gratin. With browned crumbs.

Aurora sauce. A white sauce to which lobster butter is added.

Avena. Oats.

Axafetida. A gum resin. Its taste is bitter and sub-acrid, and by the Asiatics [sic] it is used regularly as a condiment.

Baba Cakes. Cakes baked in small moulds; made from a yeast dough mixture to which is added butter, sugar, eggs, raisins, and almonds. Served as a pudding with hot sauce.

Bain-Marie. A vessel of any kind containing heated water, in which other vessels are placed in order to keep their contents heated.

Bannocks. Scottish cakes made of barley or oatmeal, cooked on a griddle.

Bards. Slices of pork or bacon to lay on the breast of game for cooking.

Basil. A pot herb.

Bay leaves. Leaves from a species of laurel.

Béarnaise (à la). In Swiss style.

Béarnaise saner. Named from Béarnaise, Swiss home of Henry VIII.

Béchamel (à la). With sauce made of chicken stock and milk or cream.

Beignet. Fritter.

Beurre noir. Black butter.

Biscuit glace. Small cakes of ice cream.

Bisque. A soup usually made from shellfish; or an ice cream to which are added finely chopped nuts.

Blanch (to). To whiten.

Blanquette. White meat in cream sauce.

Boeuf à la jardinière. Braised beef with vegetables.

Boeuf braisé. Braised beef.

Bombe glacée. Moulded ice cream and ice, or two kinds of ice cream. Outside of one kind, filling of another.

Bouchées. Literally, mouthful. Small patties.

Bouquet of herbs. A sprig each of thyme, savory, marjoram, and parsley.

Bourgeoise (à la). In family style.

Bretonne sauce. A stock sauce in which chopped parsley is served.

Café noir. Black coffee.

Cerrevelles de reau. Calf’s brains.

Chartreuse. A mould of aspic in which there are vegetables; a meat preparation filling the centre of the mould. Used to denote anything concealed.

Chateaubriand. A cut from the centre of a fillet of beef.

Chaud-froid. Literally hot cold. In cookery a jellied sauce.

Chou-fleur. Cauliflower.

Chutney. An East India sweet pickle.

Civet. A game stew.

Compotes. Fruits stewed in syrup and kept in original shape.

Con-sommé de volatile. Chicken soup.

Côtelettes. Cutlets.

Court bouillon. A highly seasoned liquor in which to cook fish.

Créole (à la). With tomatoes.

Croûte au pot. A brown soup poured over small pieces of toast.

Curry powder. A yellow powder of which the principal ingredient is turmeric. Used largely in India.

De, d’. Of.

Devilled. Highly seasoned.

Dinde farcie. Stuffed turkey.

Dinde, sauce céleri. Turkey with celery sauce.

Écossaise (à l’). In Scottish style.

En bellevue. In aspic jelly. Applied to meats.

En coquilles. In shells.

En papillotes. In papers.

Éperlans frits. Fried smelts.

Espagnole sauce. A rich brown sauce.

Farci-e. Stuffed.

Fillet de boeuf piqué. Larded fillet of beef.

Flamande (à la). In Holland style.

Foie de veay grillé. Broiled liver.

Fondue. A dish prepared of cheese and eggs.

Fraises. Strawberries.

Frappé. Semi-frozen.

Fricassée de poulet. Fricassee of chicken.

Fromage. Cheese.

Gâteau. Cake.

Gelée. Jelly.

Génevoise (à la). In Swiss style.

Glacé. Iced or glossed over.

Grilled. Broiled.

Hachis de boeuf. Beef hash.

Hoe cakes. Cakes made of white cornmeal, salt, and boiling water; cooked on a griddle.

Homard. Lobster.

Hors–d’oeuvres. Side dishes.

Huîtres en coquille. Oysters in shell.

Huîtres frites. Fried oysters.

Italienne (à l’). In Italian style.

Jambon froid. Cold ham.

Jardiniére. Mixed vegetables.

Kirschwasser. Liqueur made from cherry juice.

Kuchen. German for cake.

Kümmel. Liqueur flavored with cumin and caraway seed.

Lait. Milk.

Laitue. Lettuce.

Langue de boeuf à l’écarlate. Pickled tongue.

Macaroni au fromage. Macaroni with cheese.

Macédoine. A mixture of several kinds of vegetables.

Maigre. A vegetable soup without stock.

Maître d’hôtel. Head steward.

Mango. A fruit of the West Indies, Florida, and Mexico.

Mango pickles. Stuffed and pickled young melons and cucumbers.

Maraschino. A cordial.

Marrons. Chestnuts.

Menu. A bill of fare.

Morue. Salt cod.

Noël. Christmas.

Noir. Black.

Nouilles. Noodles.

Noyau. A cordial.

Oeufs farcis. Stuffed eggs.

Oeufs pochés. Poached eggs.

Omelette aux champignons. Omelette with mushrooms.

Omelette aux fines heroes. Omelette with fine herbs.

Pain. Bread.

Panade. Bread and milk cooked to a paste.

Paté de biftecks. Beefsteak pie.

Paté de foie gras. A paste made of fatted geese livers.

Pigeonneaux. Squabs (young pigeons).

Pois. Peas.

Pommes. Apples.

Pommes de terre. Potatoes.

Pommes de terre à la Lyonnaise. Lyonnaise potatoes.

Pone cakes. A cake made in the South, baked in the oven.

Potage. Soup.

Poulets sautés. Fried chicken.

Queues de boeuf. Ox-tails.

Ragoût. A highly seasoned meat dish.

Réchauffés. Warmed over dishes.

Removes. The roasts or principal dishes.

Ris de veau. Sweetbreads.

Salade de laitue. Lettuce salad.

Salade de légumes. Vegetable salad.

Salpicon. Highly seasoned minced meat mixed with a thick sauce.

Selle de venaison. Saddle of venison.

Sippets. English for croutons.

Soufflé. Literally, puffed up.

Soupe a l’ognon. Onion soup.

Sucres. Sweets.

Tarte aux pommes. Apple pie.

Tourte. A tart.

MEASUREMENTS

The following chart shows how much measuring standards in cooking have changed in the past century. This chart is from the book Food for the Sick and How to Prepare It by Edwin Charles French, M.D., published by J.P. Morton and Company in 1900.

| Table of Approximate Weights and Measures | |

| Three teaspoonfuls | one tablespoonful |

| Four tablespoonfuls | one wineglassful |

| two wineglassfuls | one gill |

| two gills | one tumbler or cup |

| two cups | one pint |

| one quart of sifted flour | one pound |

| one quart powered sugar | one pound, seven oz. |

| one quart granulated sugar | one pound, nine oz. |

| one pint closely packed butter | one pound |

| three cupfuls sugar | one pound |

| five cupfuls sifted flour | one pound |

| one tablespoonful salt | one ounce |

| seven tablespoonfuls granulated sugar | one-half pint |

| twelve tablespoonfuls flour | one pint |

| three coffee cupfuls | one quart |

| ten eggs | one pound |

A tablespoonful is frequently mentioned in receipts [sic]. It is generally understood as a measure or bulk equal to that which would be produced by half an ounce of water.

So what is a gill or tumbler, and how much is in a wineglass? The following lists give the modern equivalents to archaic terms.

LIQUID MEASUREMENTS

4 drams = 1 tablespoon

76 drops = 1 teaspoon

1 gill = ½ cup

1 jigger = 3 tablespoons

1 kitchen cup = 1 cup

1 pint = 2 cups

1 pottle = 2 quarts

1 saltspoon = ¼ teaspoon

1 tumbler = 1 cup

1 wine glass = ¼ cup

DRY MEASUREMENTS

1 bushel = 8 gallons (dry)

1 coffeecup = scant cup

1 dessert or soup spoon = 2 teaspoons

1 kitchen spoon = 1 teaspoon

1 peck = 2 gallons (dry)

1 pinch or dash = less than ⅛ teaspoon

1 saucer = about 1 heaping cup

1 spoonful = about 1 tablespoon

1 teacup = scant ¾ cup

This “Table of Weights and Measures” is from The Third Presbyterian Cook Book and Household Directory published in the interest of the Manse Fund by the Mite Society of the Third Presbyterian Church of Chester, Pa. (1917).

TABLE OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

“With weights and measures just and true,

Oven of even heat:

Well buttered tins and quiet nerves,

Success will be complete.”

| 4 saltspoonfuls liquid | 1 teaspoonful |

| 4 teaspoonfuls | 1 tablespoonful |

| 3 teaspoonfuls dry material | 1 tablespoonful |

| 4 tablespoonfuls liquid | 1 wineglass, ½ gill, ¼ cup |

| 16 tablespoonfuls liquid | 1 cup or ½ pint |

| 12 tablespoonfuls dry material | 1 cup |

| 1 cup liquid | ½ pint |

| 4 cups liquid | 1 quart |

| 4 cups flour | 1 quart or 1 pound |

| 2 cups granulated sugar | 1 pound |

| ½ cup butter | ¼ pound |

| 1 round teaspoonful butter | 1 ounce |

| 1 heaping teaspoonful butter | 2 ounces or ¼ cup |

A pinch of salt and spice is about a saltspoonful

COOKING TIMES AND TEMPERATURES

Modern ovens allow us to set exact temperatures with the push of a button, but our ancestors cooked first over fires and later over fuel-burning stoves. Cooking times and temperatures listed in old recipes may seem vague to modern cooks. Here are some common cooking and baking temperatures you may encounter along with the modern equivalent:

slow oven = 300 degrees Fahrenheit

moderate oven = 350 degrees

quick oven = 375 to 400 degrees

hot oven = 400 to 425 degrees

What was it like to cook with a woodburning stove? The Cooking School Text Book and Housekeepers’ Guide to Cookery and Kitchen Management by Juliet Corson, superintendent of the New York Cooking School, first published in 1877, gives a thorough explanation of how to care for the stove, build the fire, and maintain the proper cooking temperature.

How to Clean the Stove.—(1.) Let down the grate and take up the cinders and ashes carefully to avoid all unnecessary dirt; put them at once into an ash-sifter fitted into the top of a pail or keg with handles, and closed with a tight fitting cover; take the pail out of doors, sift the cinders, put the ashes into the ash-can, and bring the cinders back to the kitchen. (2.) Brush the soot and ashes out of all the flues and draught-holes of the stove, and then put the covers on, and brush all the dust off the outside. A careful cook will save all the wings of game and poultry to use for this purpose. If the stove is greasy wash it off with a piece of flannel dipped in hot water containing a little soda. (3.) Mix a little black-lead or stove polish with enough water to form a thin paste; apply this to the stove with a soft rag or brush; let it dry a little and then polish it with a stiff brush. (4.) If there are any steel fittings about the stove, polish them with emery paper; if they have rusted from neglect, rub some oil on them at night, and polish them with emery paper in the morning. A “burnisher,” composed of a net-work of fine steel rings, if used with strong hands, will make them look as if newly finished. (5.) If the fittings are brass, they should be cleaned with emery or finely powdered and sifted bath brick dust rubbed on with a piece of damp flannel, and then polished with dry dust and chamois skin. (6.) Brush up the hearthstone, wash it with a piece of flannel dipped in hot water containing a little soda, rinse, and wipe it dry with the flannel wrung out of clean hot water.

How to Light the Fire.—Put a double handful of cinders in the bottom of the grate, separating them so that the air can pass freely between them; put on them a layer of dry paper, loosely squeezed between the hands; on the paper lay some small sticks of wood cross-wise, so as to permit a draught from the bottom; place a double handful of small cinders and bits of coal on top of the wood; close the covers of the stove; open all the draughts, and light the paper from the bottom of the grate. As the fire burns up gradually add mixed coal and cinders until there is a clear, bright body of fire; then partly close the draughts, and keep the fire bright by occasionally putting on a little coal. The condition of the draught closely affects the degree of heat yielded by a given amount of fuel; just enough air should be supplied to promote combustion; but if a strong current blows through the mass of fire, or over its surface, it carries off a great portion of the heat which should be utilized for cooking purposes, and gradually deadens the fire.

How to Keep up the Fire.—As soon as the heat of the fire shows signs of diminishing, add a little fuel at a time, and often enough to prevent any sensible decrease of the degree of heat required for cooking. Keep the bottom of the fire raked clear, and never let the ash-pan get choked up near the grate with ashes, cinders, or refuse of any kind. There is no economy in allowing a fire to fail for want of fuel; if the fire is not replenished until the heat falls below the temperature necessary for cooking purposes, there is a direct waste of all the heat which is supplied by fresh fuel until the surface and ovens of the stove are again heated to the proper degree; whereas, if, when that heat has once been reached, it is sustained by the gradual addition of a little fuel at a time, this waste is avoided, and much of the cook’s time is saved. In kitchens where this fact is not understood there is a continual waste of time and fuel, to say nothing of the trial of patience which is the too apt response to a request for the services of the cook when she has just mended the fire, and nothing can be cooked until it burns up.

Degrees of Heat from Fuel.—The advantage which one kind of fuel possesses over another depends upon its local abundance and cheapness. We append the average temperature of a clear fire made of different combustibles, and a table of the degree of heat necessary for various operations in cookery, so that some definite idea of the relative values of fuel can be reached:

| Willow Charcoal | 600° | Fahr. |

| Ordinary | 700 | ” |

| Hard Wood | 800 to 900 | ” |

| Coal | 1,000 | ” |

Shell-bark Hickory has the greatest heating value among woods; that is, the coals it produces are hotter and retain the heat longer than the coals from soft woods. Soft woods burn with a quicker flame and more intense heat than hard woods, and produce more flame and smoke; they are therefore best to make a quick, fierce fire. Hard woods burn more slowly, with less heat, flame, and smoke, but produce harder coals, which retain the heat, and are consequently the best for long continued cooking operations.

Charcoal is the residue of wood, the gaseous elements of which have slowly been burned away in covered pits or furnaces, with a limited supply of air. Newly-made charcoal burns without flame, but after it has gathered moisture from exposure to the air it makes a slight blaze; it burns easily and rapidly, and produces a greater heat in proportion to its weight than any other fuel.

Anthracite coal is the mineral remains of ancient vegetation which has lost all its elements except a little sulphur, an excess of carbon and the incombustible ash. It kindles slowly, but burns with an intense and steady volume of heat which is exceedingly valuable for cooking purposes.

Coke, the residue of any kind of coal from which illuminating gas has been manufactured, is an inexpensive fuel, yielding an intense but transient heat, and is very well adapted for boiling and for cooking operations which do not require long sustained heat.

Prof. Youmans quotes the following figures as representing the comparative heating values of the above named fuels, but remarks that the actual degree of heat derived from them, under ordinary circumstances, will fall below this estimate: 1 lb. of dry, hard wood will raise 35 lbs. of water from the freezing to the boiling point; 1 lb. of coal will similarly heat 60 lbs. of water; and 1 lb. of wood charcoal, 73 lbs. of water.

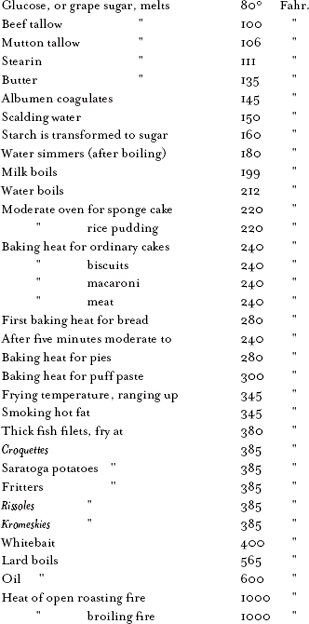

Cooking Temperatures.—The following table represents the degrees of heat to which food is subjected during its preparation for the table:

This “Time Table of Cooking” is from The Third Presbyterian Cook Book and Household Directory published in the interest of the Manse Fund by the Mite Society of the Third Presbyterian Church of Chester, Pa. (1917).

TIME TABLE OF COOKING

| Loaf Bread | 40 to 60 minutes |

| Rolls and Biscuits | 10 to 20 minutes |

| Graham Gems | 30 minutes |

| Gingerbread | 20 to 30 minutes |

| Sponge Cake | 45 to 60 minutes |

| Plain Cake | 30 to 40 minutes |

| Fruit Cake | 2 to 3 hours |

| Cookies | 10 to 15 minutes |

| Bread Pudding | 1 hour |

| Rice and Tapioca | 1 hour |

| Indian Pudding | 2 to 3 hours |

| Steamed Pudding | 1 to 3 hours |

| Steamed Brown Bread | 3 hours |

| Custards | 15 to 20 minutes |

| Pie Crusts | About 30 minutes |

| Plum Pudding | 2 to 3 hours |