FIGURE 4.1 Click this tile or icon to create a blank file.

IN THIS CHAPTER

Making a new blank file or using a template

Reopening a saved document

Saving a document

Reviewing file formats and compatibility issues

Navigating in a document and selecting text

Using Word’s various views

When a coach teaches someone a new sport, he or she starts with the fundamentals. Eager students often want to skip the basics — especially when in a rush to be productive with new software — and what they miss out on learning now can trip them up later. This chapter starts with the essential skills that will serve you well every time you work with Word 2013. If you’re new to Word, this chapter makes getting started painless. If you’ve been using Word for years, you may not only pick up some tricks you previously missed, but also get an introduction to a few new features in the latest version of Word. You also explore creating files, saving and reopening files, navigating in the text and making selections, and viewing variations.

When you start the Word 2013 application, the upper-left choice in the collection of templates that appears is Blank document. Selecting it creates a new, blank document file by default for you. (The actual name of the template applied to new, blank files is Normal.dotm.) This document file has the placeholder name Document1 until you save it to assign a more specific name, as described later in the chapter. You can immediately start entering content into this blank document.

If you need another blank document at any time after starting Word, you can create it by following these steps:

Clicking Ctrl+N also creates a new, blank file directly.

FIGURE 4.1 Click this tile or icon to create a blank file.

When you create a new, blank document, you can begin typing text to fill the page. As you type, each character appears to the left of the blinking vertical insertion point. You can use the Backspace and Delete keys to delete text, the Spacebar to enter spaces, and all the other keys that you’re using for typing.

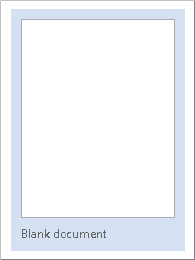

Word also enables you to start a line of text anywhere on the page using the Click and Type feature. To take advantage of Click and Type, move the mouse pointer over a blank area of the page. If you don’t see formatting symbols below the I-beam mouse pointer, click once. This enables Click and Type and displays its special mouse pointer. Then, you can double-click to position the pointer on the page and type your text. Figure 4.2 shows snippets of text added to a page using Click and Type.

FIGURE 4.2 Double-click and type anywhere on the page.

By default, the margins for a blank document in Word 2013 are 1 inch on the left and the right. When you type enough text to fill each line, hitting the right margin boundary, Word automatically moves the insertion point to the next line. This automated feature is called word wrap, and it’s a heck of a lot more convenient than having to make a manual carriage return at the end of each line.

If you adjust the margins for the document, word wrap always keeps your text within the new margin boundaries. Similarly, if you apply a right indent, divide the document into columns, or create a table and type in a table cell, word wrap automatically creates a new line of text at every right boundary. Just keep typing until you want or need to start a new paragraph (covered shortly). Later chapters cover changing margins and indents and working with tables and columns.

Like its prior versions, Word 2013 offers two modes for entering text: Insert mode and Overtype mode. In Insert mode, the default mode, if you click within existing text and type, Word inserts the added text between the existing characters, moving text to the right of the insertion point farther right to accommodate your additions and rewrapping the line as needed. In contrast, when you switch to Overtype mode, any text you type replaces text to the right of the insertion point.

Overtyping is a fine method of data entry — when it’s the mode that you want. Unfortunately, in older Word versions, the Insert key on the keyboard toggled between Insert and Overtype modes by default. Because the Insert key is often found above or right next to the Delete key on the keyboard, many a surprised user would accidentally hit the Insert key and then unhappily type right over his text.

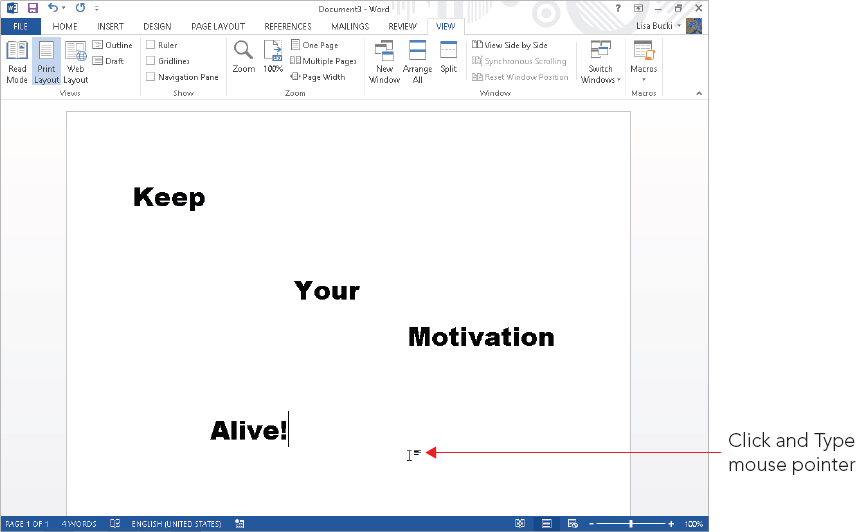

In Word 2013, the Insert key’s control of Overtype mode is turned off by default. You can use the Word Options dialog box to turn Overtype mode on and off, and also to enable the Insert key’s control of Overtype mode. Select File ⇒ Options, and then click Advanced in the list at the left side of the Word Options dialog box. Use the Use overtype mode check box (Figure 4.3) to toggle Overtype mode on and off, and the Use the Insert key to control overtype mode check box to toggle the Insert key’s control of Overtype mode on and off. Click OK to apply your changes.

FIGURE 4.3 The Word Options dialog box enables you to turn Overtype mode on and off.

Every new, blank document has default tab stops already set up for you. These tabs are set at 1/2-inch (0.5-inch) intervals along the whole width of the document between the margins. To align text to any of these default tab stops, press the Tab key. You can press Tab multiple times if you need to allow more width between the information that you’re using the tab stops to align.

In legacy versions of Word, when you wanted to create a new paragraph in a blank document, you had to press the Enter key twice. That’s because the default body text style didn’t provide for any extra spacing after a paragraph mark, which is a hidden symbol inserted when you press Enter.

Starting with Word 2007, pressing Enter by default not only inserts the paragraph mark to create a new paragraph, but also inserts extra spacing between paragraphs to separate them visually and eliminate the need to press Enter twice. As shown in Figure 4.4, when you press Enter after a paragraph, the insertion point moves down to the beginning of a new paragraph, and Word includes spacing above the new paragraph.

FIGURE 4.4 Press Enter to create a new paragraph in Word.

Every new document you create in Word 2013 — even a blank document — is based on a template that specifies basic formatting for the document, such as margin settings and default text styles. When you create a blank document, Word automatically applies the default global template, Normal.dotm.

While a document theme supplies the overall formatting for a file, a template takes that a step further. A template may not only include particular text and document formatting selections, but also has placeholders and example text as you saw when you created your first document earlier in the chapter. Templates also can contain automatic macros that swing into action each time you create, open, or close a document, as well as other macros you can use to perform tasks for building the document.

Using templates can dramatically reduce the amount of time you spend thinking about your document’s content and formatting, because someone else has already invested the time to answer those questions. For example, a home repair company might set up a template for written estimates, job contracts, and change orders. Rather than starting every such document from scratch, the project manager could simply create a new document using the applicable template, and fill in the information pertinent to the current client.

In that type of scenario or in your business and personal life, using templates offers the following benefits:

Take a look at the templates available to you via Word now.

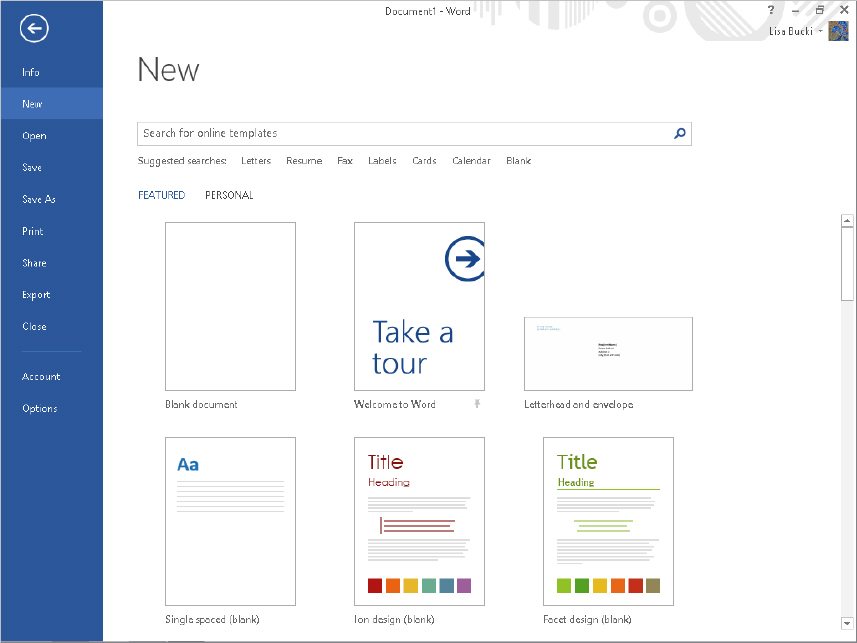

When you start Word 2013 or click File ⇒ New, the right pane of the screen displays a selection of templates, shown in Figure 4.5. You can scroll down this screen to see a selection of suggested templates. Note that the available templates will vary depending on whether your computer is connected to the Internet and you are signed in to Word with your account information to enable online features.

FIGURE 4.5 Starting Word or clicking File ⇒ New shows you Word’s templates.

The Blank document template always appears among the templates. Selecting it creates a new document based on Normal.dotm. Figure 4.5 also shows a Letterhead and envelope template. Once you download and use a template, it will appear the next time you choose File ⇒ New, because Word automatically includes recently used templates in the list. If you look carefully at Figure 4.5, you’ll see a small pushpin icon to the right of the Welcome to Word template name. That means that item is pinned to stay on the list of templates. To pin or unpin a template, point to its thumbnail, move the mouse pointer over the pushpin icon, and click the icon to toggle it to be pinned or unpinned.

Common templates you might want to pin to the list include:

To create a blank document based on Normal.dotm, you could simply press Ctrl+N, bypassing the need to choose the New command.

Virtually all of the templates in Word 2013 exist in the cloud rather than being installed on your computer. In addition to the suggested templates shown when you click File ⇒ New, you can scroll down to see and select additional templates. Any template that you select is downloaded to your system and stored there for future use.

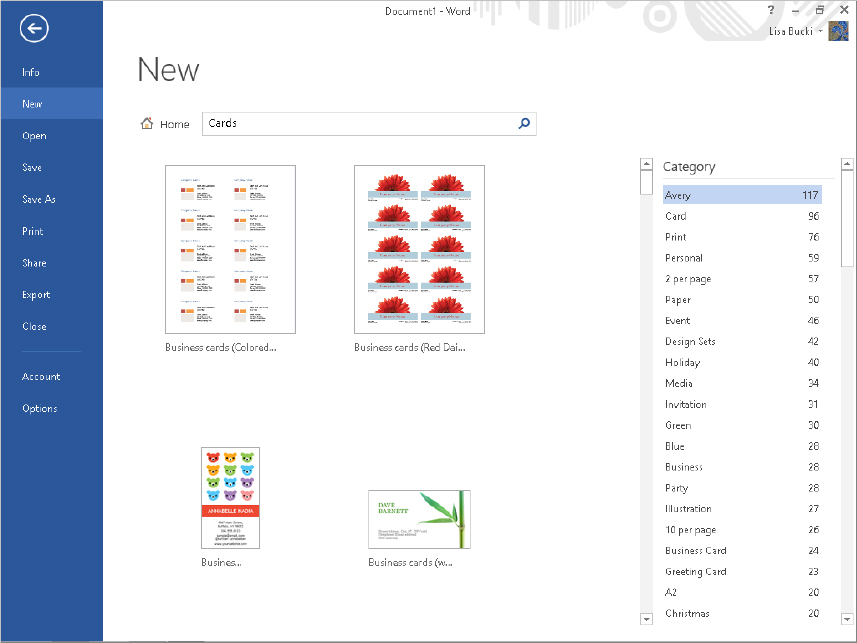

If you don’t see a template that suits your needs, you can search online for additional templates. You can type a search word or phrase in the Search online templates text box above the templates and press Enter to begin a search. Or you can click one of the Suggested searches links below the Search online templates text box, such as Cards. After the search runs, scroll down to view additional results, or use the Filter by list at the right (see Figure 4.6) to refine the results.

FIGURE 4.6 You can refine the Cards search by clicking the Avery (or another) category under Filter by in the right pane.

Now that you’re familiar with what templates do and where to find them, follow these steps when you want to create a new document based on a template:

The new document appears on-screen.

As shown in Figure 4.7, a template might hold a variety of sample contents and placeholders.

FIGURE 4.7 Replace template placeholders with your own content.

You can work with these placeholders and other contents as follows to finish your document:

Even the best writers revisit their work to edit and improve it. You will typically work on a given Word document any number of times, whether to correct spelling and grammar errors, rearrange information, update statistics and other details, or polish up the formatting.

You learned in Chapter 2 that you can choose File ⇒ Open to display a list of Recent documents, which you can pin or unpin for faster access. The left pane of the Word 2013 Start screen displays the list of Recent documents as well, and you can also pin and unpin files there by clicking the pushpin icon that appears when you point to the right side of the file name.

As you might guess, you can open an existing file by clicking it in the Recent files list on either the Word Start screen or the Open screen.

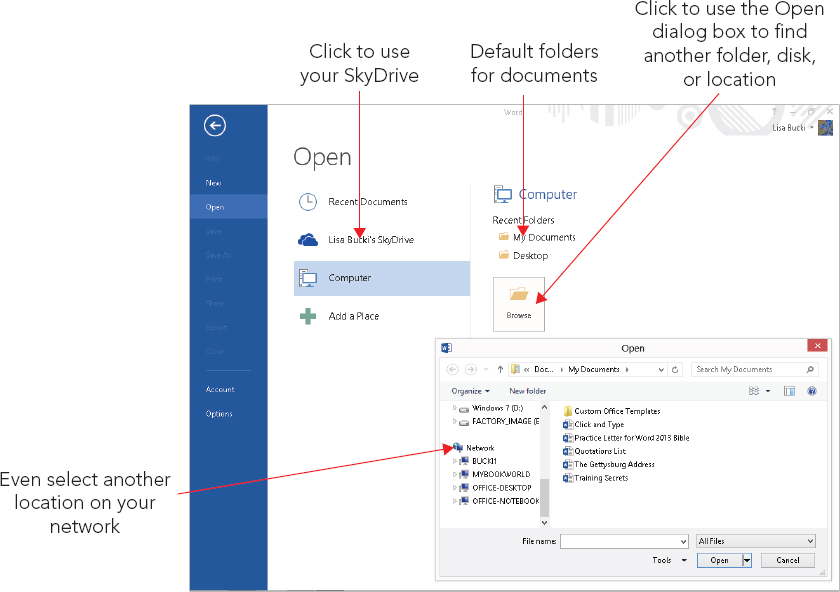

However, the Recent files list is dynamic, so if your document no longer appears there, you will need to navigate to it and open it from the location where you saved it. (The next section covers saving.) You can save documents to and open them from one of two overall locations from the Open screen:

FIGURE 4.8 You can open files stored on your computer or network.

For now, use these steps to open a file that’s not on the Recent files list:

As long as you see “Document1” in Word’s title bar, you run the risk of losing your investment of time and creativity if a power surge zaps your computer or Word crashes. Even for previously saved files, you should save your work often to ensure that you won’t have to redo much work should something go wrong. Saving in Word works as it does in most other apps, with a few variations based on how you want to use or ultimately share the document.

The first time you save any file, even one created from a template, you will choose the location where you want to save it, and give the file a meaningful name. Word will suggest a name that’s based on the first line of text in the document, but chances are it won’t provide the benefit of making the file easy to find when you need to reopen it. I always recommend establishing a consistent file-naming system, particularly when you create many similar files. Including the date and client or contact person name in the file name are two tricks. For example, Smith Systems Marketing Plan 12-01-15 is more descriptive than Smith Marketing or even Smith Marketing v1. When viewing dated file names, you can easily see which one’s the latest and greatest. Word automatically adds the .docx extension to every file saved in the default format. This section and the next present more ins and outs concerning file formats.

Here’s how to save a file for the first time:

After you’ve named the file, you can press Ctrl+S or choose File ⇒ Save to save the current document.

If you want to create a copy of the file, save it, and then choose File ⇒ Save As. This reopens the Save As dialog box. You can choose another save location and enter another file name, and then click Save to create the file copy. Changes you make to the copy appear only there. Save As is a quick and dirty alternative to setting up a template. The upside is that you may have less text to replace than with a template. The downside is that you may forget to update text that needs changing that otherwise would not have been in the template.

Not every user immediately upgrades to the latest version of a particular program or uses the same platform as each of us. Nearly every Word user experiences a situation where they need to convert a document to another file format so someone else can open it on their computer or other device. And there may be instances where you need to save a document as a web page for addition to a website, as a PDF file that can be opened on an iPad, and so on. Word can handle other file formats for both incoming and outgoing files.

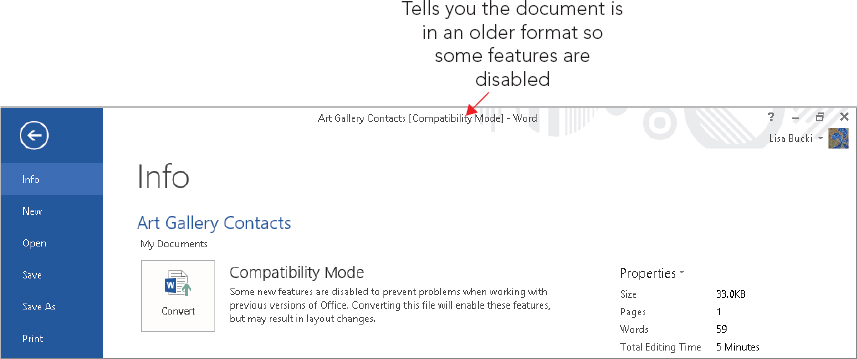

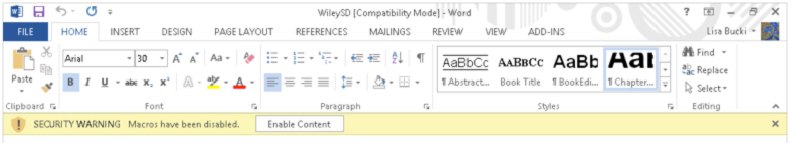

When you open a file in Word 2013 that was created in an earlier version of Word, [Compatibility Mode] appears in the title bar to the right of the file name. In this mode, some of the latest features in Word are disabled so that you can still use the file easily in an older Word version. In some cases, you may prefer to convert the file to the current Word format to take advantage of all Word’s features. The only caution is that this can result in some layout changes to the document. If that’s worth it to you, then by all means, convert the file. Even though Word 2007 and Word 2010 files use the same .docx file name extension as for Word 2013, the formats are not precisely identical, so even files from those versions may need to be converted.

FIGURE 4.9 Convert a file to the current Word format and leave Compatibility Mode.

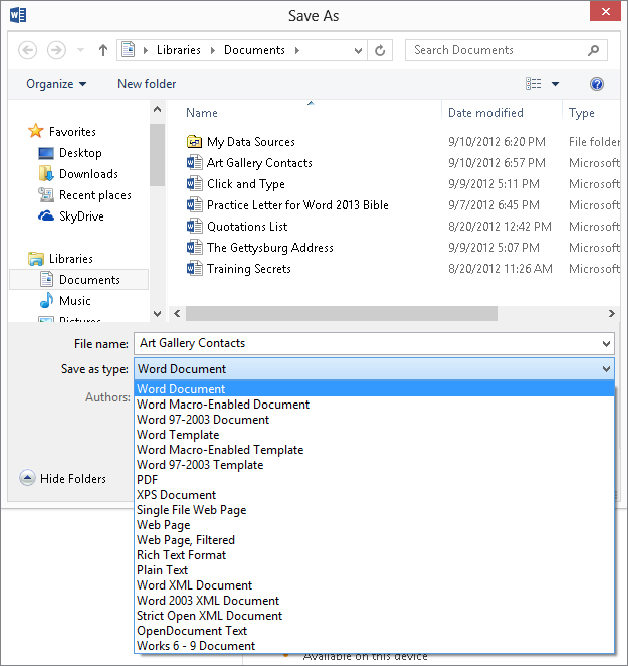

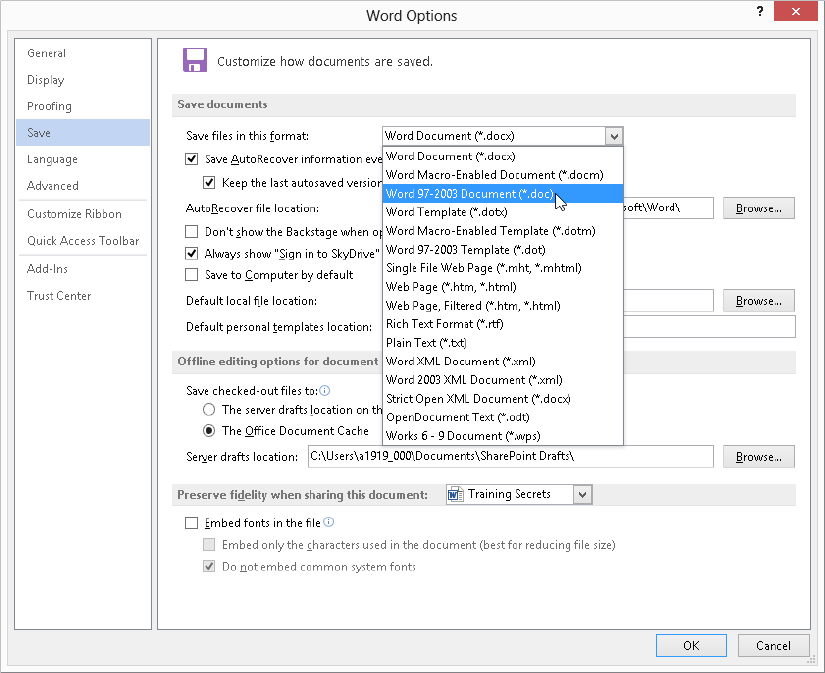

The Save As dialog box includes a Save as type drop-down list directly below the File name text box. After you choose File ⇒ Save As, click Save as type to display the choices shown in Figure 4.10. Click a choice in the list, specify the file name, and then click Save. Word saves the file in the designated format, adding the file name extension for that format.

FIGURE 4.10 Use the Save as type drop-down to select another file format.

You might notice added behavior in the Save As dialog box when you select certain file types. For example, if you click Word Template, the folder specified for the save changes automatically. This is because storing your Office templates in a centralized location makes them easier to use. In an example like this, it’s usually best to stick with the change suggested in the Save As dialog box and just click Save.

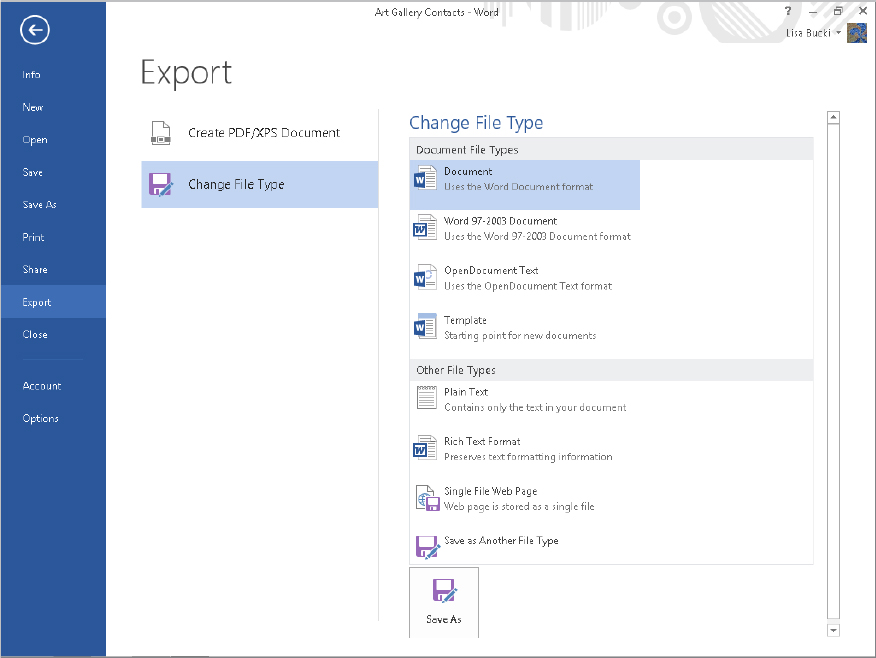

If you need to save a file in another common format, you might choose to use the File ⇒ Export ⇒ Change File Type command instead. As shown in Figure 4.11, choosing this command opens an Export screen with a Change File Type list at the right. Word gives a small description of each of the file types there to make it easier to select the right one. Click the format to use, and then click Save As. Word opens the Save As dialog box with the specified format already selected for Save as type. From there, specify a file name and save location as usual, and click Save.

FIGURE 4.11 Learn more about and choose an alternate save format on the Export screen.

Between the 97 and 2003 versions of Word, the .doc file format remained basically unchanged. Feature enhancements, such as document versioning and floating tables, necessitated some modifications to the file format.

Even so, you can still open most Word 2003 files in Word 97 and the documents will look basically the same. Only if you use newer features will you see a difference, and usually that just means reduced functionality rather than lost data or formatting. However, when it comes to post-2003 versions of Word, file format changes introduce meaningful differences.

Word 2013, Word 2010, Word 2007, and Word 2003 users will continue to see interoperability. However, Word 2013’s, 2010’s, and 2007’s “native” format is radically different — and better — than the old format. The new format boasts a number of improvements over the older format:

Calling the x-file format “XML format” actually is a bit of a misnomer. XML is at the heart of Word’s x format; however, the files saved by Word are not XML files. You can verify this by trying to open one using Internet Explorer. What you see is decidedly not XML. Some of the components of Word’s x files, however, do use XML format.

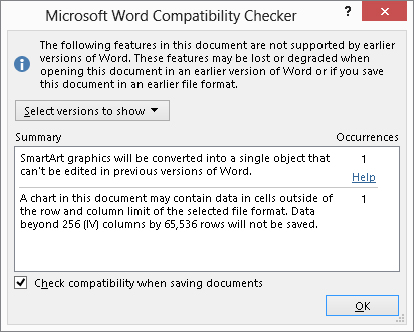

Word runs an automatic compatibility check when you attempt to save a document in a format that’s different from the current one. You can, without attempting to save, run this check yourself at any time from Word 2013. To see whether features might be lost in the move from one version of Word to another, open the document in Word 2013. Choose File ⇒ Info ⇒ Check for Issues ⇒ Check Compatibility.

For the most part Word 2013 does a good job of checking compatibility when trying to save a native .docx file in .doc format. For example, if you run the Compatibility Checker on a Word 2013 document containing advanced features, you will be alerted, as shown in Figure 4.12.

FIGURE 4.12 Using the Compatibility Checker to determine whether converting to a different Word version will cause a loss of information or features.

When moving in the other direction — checking a Word 2003 (or earlier) document for compatibility with Word 2013 — the checker usually will inform you that “No compatibility issues were found.” Note, however, that the Compatibility Checker doesn’t check when you first open a document formatted for Word 2003 (or earlier). It’s not until you try to save the file that it warns you about any unlikely issues.

Word’s options enable you to choose to save in the older .doc format by default. A person may opt to do this, for example, if the majority of users in his or her organization still use Word 2003 or earlier. That’s certainly a plausible argument, but consider one occasional down side to Word’s binary .doc format. With a proprietary binary file format, the larger and more complex the document, the greater the possibility of corruption becomes, and it’s not always possible to recover data from a corrupted file.

Another issue is document size. Consider a simple Word document that contains just the phrase “Hello, Word.” When saved in Word 97–2003 format, that basic file is 26K. That is to say, to store those 11 characters it takes Word about 26,000 characters!

The same phrase stored in Word 2013’s .docx format requires just 11K. Make no mistake: That’s still a lot of storage space for just those 11 characters, but it’s a lot less than what’s required by Word 2003. The storage savings you get won’t always be that dramatically different, but over time you will notice a difference. Smaller files mean not only lower storage requirements but faster communication times as well.

Still another issue is interoperability. When a Word user gives a .doc file to a user of WordPerfect or another word processor, it’s typical that something is going to get lost in translation, even though WordPerfect claims to be able to work with Word’s .doc format. Such documents seldom look identical or print identically, and the larger and more complex they are, the more different they look.

With Word’s adoption of an open formatting standard, it is possible for WordPerfect and other programs to more correctly interpret how any given .docx file should be displayed. Just as the same web page looks and prints nearly identically when viewed in different web browsers, a Word .docx file should look and print nearly identically regardless of which program you use to open it (assuming it supports Word’s .docx format).

If, despite the advantages of using the new format, you choose to use Word’s .doc format, you can do so. Choose File ⇒ Options ⇒ Save tab. As shown in Figure 4.13, set Save files in this format to Word 97–2003 Document (*.doc).

FIGURE 4.13 You can tell Word to save in any of a variety of formats by default.

Note that even if you set .doc or some other format as your default you can still override that setting at any time by using Save As and saving to .docx or any other supported format. Setting one format as the default does not lock you out of using other formats as needed.

As of this writing, users of legacy versions of Word such as Word 2003 could open Word 2007, 2010, and 2013 files after installing a Compatibility Pack. While the Compatibility Pack was not developed specifically for Word 2013 files, in my testing, I was able to open a Word 2013 file in Word 2003 with the Compatibility Pack installed. The Compatibility Pack is a free downloads found at http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=3. Or, go to www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/default.aspx. Click in the Search Download Center text box at the top, type Compatibility Pack, and press Enter. Check the Search results for “Microsoft Office Compatibility Pack for Word, Excel, and PowerPoint File Formats,” and download it. At this time, that was the latest version of the Compatibility Pack available, but it’s possible an update could be released at a later time.

Word 2013 uses four primary XML-based file formats:

It is important for some purposes for users to be able to include macros not just in document templates, but in documents as well. This makes documents that contain automation a lot more portable. Rather than having to send both document and template — or, worse, a template masquerading as a document — you can send a document that has macros enabled.

Because Word 2003 documents can contain legitimate macros, there is no outward way to know whether any given .doc document file contains macros. If someone sends you a .doc file, is opening it safe?

Though it’s not clear that the new approach — distinct file extensions for documents and templates that are macro-enabled — is going to improve safety a lot, it does provide more information for the user. This is true especially in business environments, where people don’t deliberately change file extensions. If you see a file with a .docm or .dotm extension, you know that it likely contains macros, and that it might warrant careful handling.

If you want to convert a .docx file so that it can contain macros, you must use Save As and choose Word Macro-Enabled Document as the file type. You can do this at any time — it doesn’t have to be when the document is first created. You can also remove any macros from a .docm file by saving it as a Word document (∗.docx).

Even so, you can create or record a macro while editing a .docx file, and even tell Word to store it in a .docx file. There will be no error message, and the macro will be available for running in the current session. However, when you first try to save the file, you will be prompted to change the target format or risk losing the VBA project. If you save the file as a .docx anyway and close the file, the macro will not be saved.

Bible readers already know the basics of using the Windows interface, so this book skips the stuff that I think every Windows user already knows about, and instead covers aspects of Word you might not know about. In our great hurry to get things done, ironically, we often overlook simple tricks and tips that might otherwise make our computing lives easier and more efficient.

When you want to make a change in Word, such as formatting text, you have to select it first. This limits the scope of the change to the selection only. Word lets you take advantage of a number of selection techniques that use the mouse or the mouse and keyboard together.

Dragging is perhaps the most intuitive way to select text, and it works well if your selection isn’t limited to a complete unit such as a word or sentence. Simply move the mouse pointer to the beginning of what you want to select, press and hold the left mouse button, move the mouse to extend the selection highlighting, and release the mouse button to complete the selection.

When you triple-click inside a paragraph, Word selects the entire paragraph. However, where you click makes a difference. If you triple-click in the left margin, rather than in a paragraph, and the mouse pointer’s shape is the arrow shown in Figure 4.14, the entire document is selected.

FIGURE 4.14 A right-facing mouse pointer in the left margin indicates a different selection mode.

Is triple-clicking in the left margin faster and easier than pressing Ctrl+A, which also selects the whole document? Not necessarily, but it might be if your hand is already on the mouse. In addition, if you want the MiniBar to appear, the mouse method will summon it, whereas Ctrl+A won’t.

Want something faster than triple-clicking? If you just happen to have one hand on the mouse and another on the keyboard, Ctrl+click in the left margin. That also selects the entire document and displays the Mini Toolbar.

If you Ctrl+click in a paragraph, the current sentence is selected. This can be handy when you want to move, delete, or highlight a sentence. As someone who sometimes highlights as I read, I also find that this can help me focus on a particular passage when I am simply reading rather than editing.

If you Alt+click a word or a selected passage, that looks up the word or selection using Office’s Research pane. This method of displaying the Research pane can just be a little faster than selecting one of the Proofing group options on the Review tab.

You can use Alt+drag to select a vertical column of text — even if the text is not column oriented. This can be useful when you are working with monospaced fonts (where each character has the same width) and there is a de facto columnar setup. Note that if the text uses a proportional font (where character widths vary), the selection may appear to be irregular, with letters cut off as shown in Figure 4.15.

FIGURE 4.15 With the Alt key pressed, you can drag to select a vertical swath of text.

Click where you want a selection to start, and then Shift+click where you want it to end. You can continue Shift+clicking to expand or reduce the selection. This technique can be useful if you have difficulty dragging to highlight exactly the selection you want.

A few versions of Word ago, it became possible to make multiple noncontiguous selections in a document. While many know this, many more don’t. To do it, make your first selection. Then, hold down the Ctrl key to make additional selections. Once you’ve made as many selections as you want, you can then apply the desired formatting to them, copy all of the selections to the Clipboard, paste the contents of the Clipboard over all of the selections, and so forth.

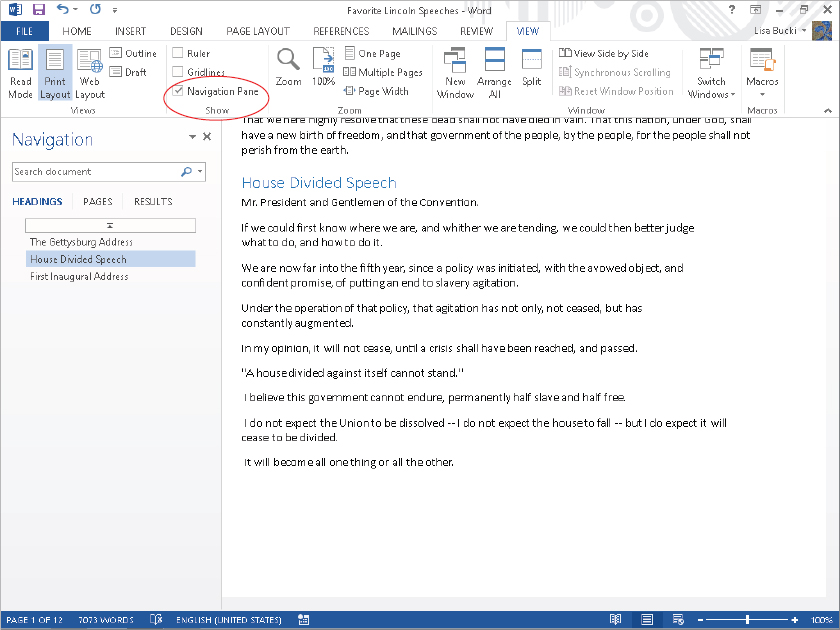

You can press Page Up or Page Down to scroll a document a screen at a time, but that can become tedious for a lengthy document such as a report or book chapter. Word includes a Navigation pane that enables you to use three quick methods for navigating in a document. To display the Navigation pane, check the View ⇒ Show ⇒ Navigation Pane check box visible in Figure 4.16.

FIGURE 4.16 Use the Navigation pane to move around a long document quickly.

Once you’ve displayed the pane, here’s how to use it:

Clear the Navigation Pane check box or select the pane’s Close (X) button to close the Navigation pane.

Word 2013 continues to offer you the option of performing many tasks via keyboard shortcuts. If you’re a highly skilled typist, using keyboard shortcuts can save time over using the mouse, because you never have to lift your hands off the keyboard. For example, say you’re typing and want to underline a word for emphasis. Just before typing the word, press Ctrl+U to toggle underlining on. Type the word, and then press Ctrl+U again to toggle the underlining back off.

In addition to keyboard shortcuts for applying formatting, Word enables you to use keyboard shortcuts to navigate in a document, perform tasks such as inserting a hyperlink, or select commands from the Ribbon (using KeyTips, as described in Chapter 2). This section helps to round out your knowledge of keyboard shortcuts in Word 2013.

Word boasts a broad array of keystrokes to make writing faster. If you’ve been using Word for a long time, you very likely have memorized a number of keystrokes (some of them that apply only to Word, and others not) that make your typing life easier. You’ll be happy to know that most of those keystrokes still work in Word 2013.

Rather than provide a list of all of the key assignments in Word, here’s how to make one yourself:

If you’ve reassigned any built-in keystrokes to other commands or macros, your own assignments appear in place of Word’s built-in assignments. If you’ve redundantly assigned any keystrokes, all assignments will be shown. For example, Word assigns Alt+F8 to ToolsMacro. If you also assigned Ctrl+Shift+O to it, your commands table would include both assignments. The table also shows those assignments and commands you haven’t customized.

One of Microsoft’s aims was to assign as many legacy menu keystrokes as possible to the equivalent commands in Word 2007, 2010, and 2013, so if you’re used to pressing Alt+I,B to choose Insert ⇒ Break in Word 2003, you’ll be glad to know it still works. So does Alt+OP, for Format ⇒ Paragraph.

Now try Alt+HA for Help ⇒ About. It doesn’t work. In fact, none of the Help shortcuts work, because that Alt+H shortcut is reserved for the Ribbon’s Home tab. Some others don’t work, either.

Some key combinations can’t be assigned because the corresponding commands have been eliminated. There are very few in that category. Some other legacy menu assignments haven’t been made in Word 2013 because there are some conflicts between how the new and old keyboard models work. There are, for example, some problems with Alt+F because that keystroke is used to select the File tab. For now at least, Microsoft has resolved to use a different approach for the Alt+F assignments. Press Alt+I and then press Alt+F to compare the different approaches.

You can also make your own keyboard assignments. To get a sneak peek, choose File ⇒ Options ⇒ Customize Ribbon, and then click the Customize button beside Keyboard shortcuts under the left-hand list.

If you prefer to highly customize the keyboard shortcuts, you can assign Alt+K (it’s unassigned by default) to the ToolsCustomizeKeyboard command. Then, whenever you see something you want to assign, pressing Alt+K will save you some steps. To assign Alt+K to that command:

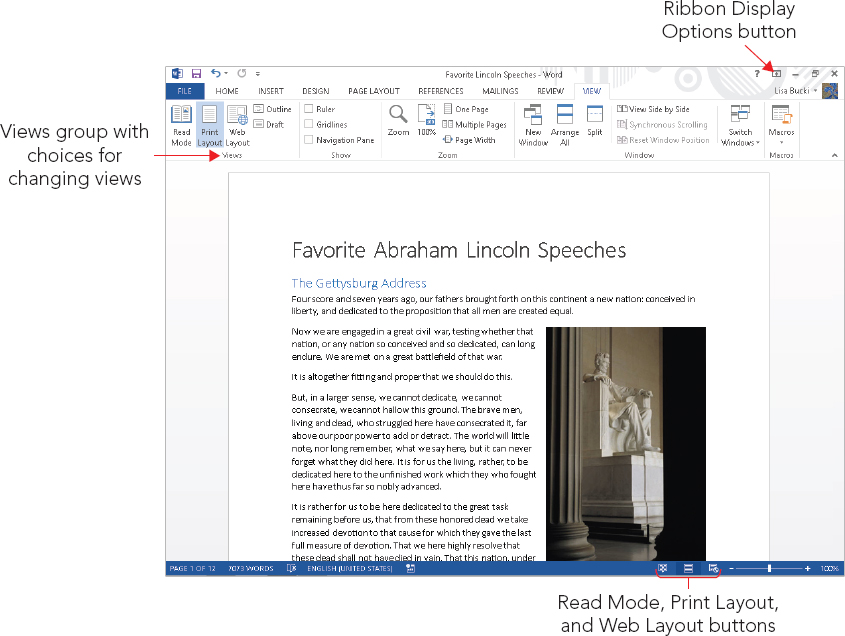

To expand the ways of working with documents, Word offers a number of different environments you can use, called views. For reading and performing text edits on long documents with a minimum of UI (user interface) clutter, you can use the Read Mode view. For composing documents and reviewing text and basic text formatting, you can choose a fast-display view called Draft view.

For working with documents containing graphics, equations, and other nontext elements, where document design is a strong consideration, there’s Print Layout view. If the destination of the document is online (Internet or Intranet), Word’s Web Layout view removes paper-oriented screen elements, enabling you to view documents as they would appear in a web browser.

For organizing and managing a document, Word’s Outline view provides powerful tools that enable you to move whole sections of the document around without having to copy, cut, and paste. An extension of Outline view, Master Document view enables you to split large documents into separate components for easier management and workgroup sharing.

Change to most of the views using the Views group of the Ribbon’s View tab.

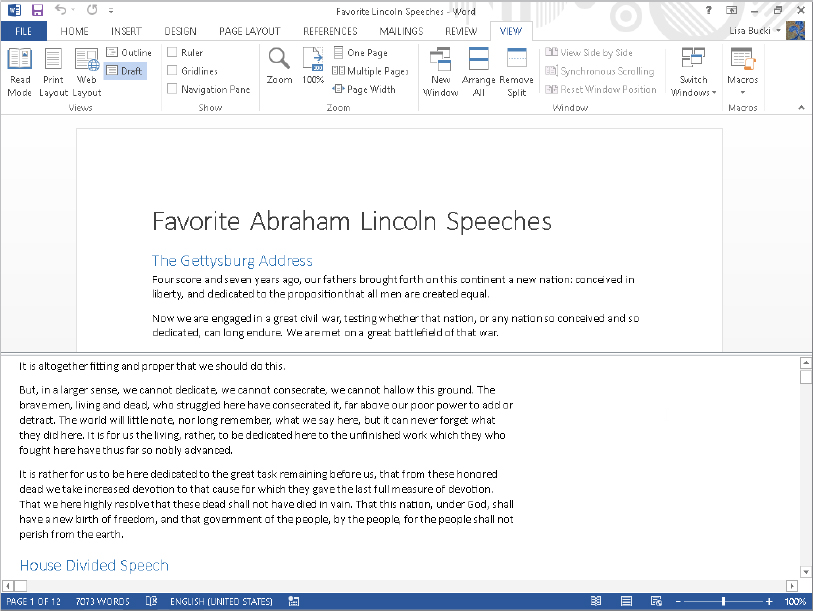

Print Layout is Word 2013’s default view, and one that many users will be comfortable sticking with. One of Word 2013’s strongest features, Live Preview, works only in Print Layout and Web Layout views.

Print Layout view shows your document exactly as it will print, with graphics, headers and footers, tables, and other elements in position. (One exception: Although you can see comments in this view, they do not print by default.) It presents an accurate picture of the margin sizes and page breaks, so you will have a chance to page through the document and make design adjustments, such as adding manual page breaks to balance pages or using shading and paragraph borders to set off text. Figure 4.17 shows this workhorse view.

FIGURE 4.17 Print Layout view reproduces how the printed document will look.

Change back to this view at any time with View ⇒ Views ⇒ Print Layout, or click the Print Layout button on the status bar, near the zoom slider.

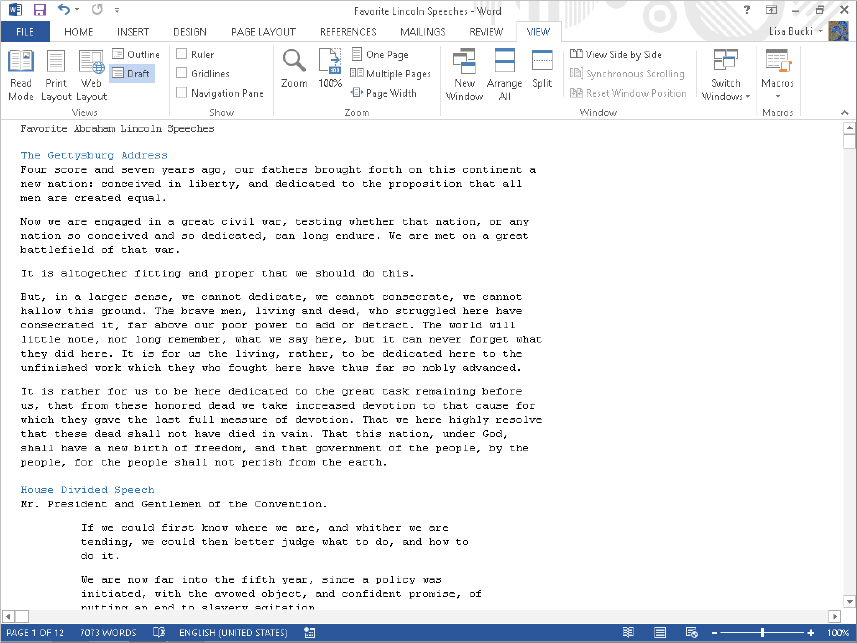

When you want to focus on crafting the text of your document, you can turn to Draft view. Choose View ⇒ Views ⇒ Draft to flip your document to this view. Draft view hides all graphics and the page “edges” so that more text appears on-screen. By default, it continues to display using the styles and fonts designated in the document.

You can further customize Draft view to make the text even plainer. Choose File ⇒ Options. In Word’s Options dialog box, click Advanced at the left, and then scroll down to the Show document content section. Near the bottom of the section, notice the option to Use draft font in Draft and Outline views. Check this option to enable it, and then use the accompanying Name and Size drop-downs to select the alternate text appearance. Click OK to apply the changes. For an example, Figure 4.18 shows Draft view customized to use 10 pt. Courier New font for all styles.

FIGURE 4.18 You can customize Draft view to use a plainer font.

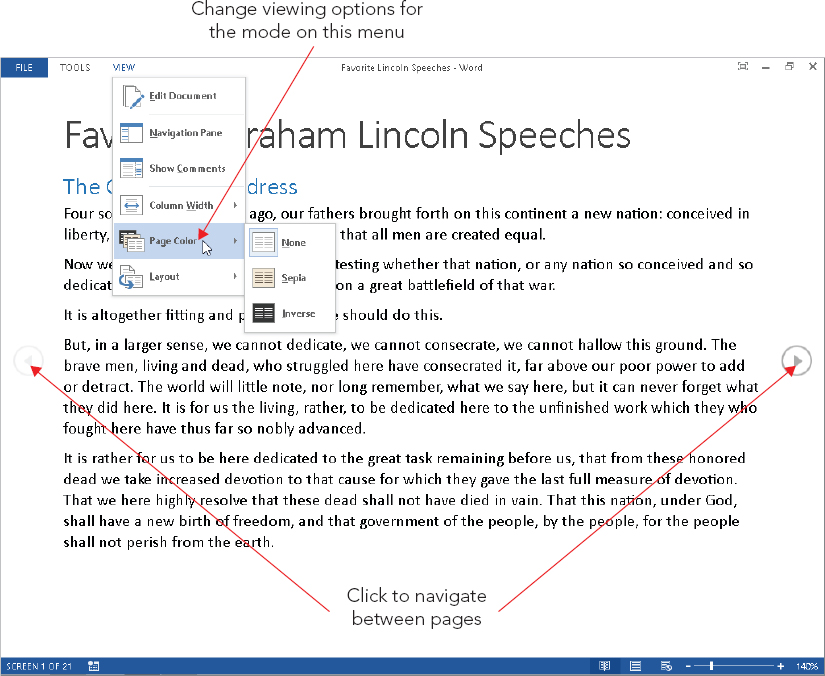

Read Mode, new in Word 2013, displays a limited number of tools, zooms the document to a larger size, and repaginates it for reading. You can’t edit document text in this view, but you can move and resize other objects, such as pictures. Use the arrow buttons to the left and right of the text to page through the text. (This latter functionality seems tailor made for touch-enabled devices.) Use this mode’s View menu to change some of the on-screen features. For example, as shown in Figure 4.19, you can choose another page background color to make your eyes more comfortable while reading. You also can display and hide the Navigation pane or Comments, change Column with, or change the overall Layout of the view. The Tools menu enables you to find document contents or search the web with Microsoft’s Bing for a highlighted text selection.

FIGURE 4.19 Kick back and enjoy your document’s contents in Read Mode.

One great feature of the Read Mode view is that it enables you to zoom in on graphics in the document. Double-click a graphic to display the zoomed version of it, as shown in Figure 4.20. Clicking the button with the magnifying glass at the upper-right corner of the zoomed content zooms in one more time. To close the zoomed object, press Esc or click outside it on the page.

FIGURE 4.20 Double-click a graphic to zoom in on it in Read Mode.

If you want, you can use the Auto-hide Reading Toolbar button at the upper-right to hide even the few menus in the view. From there, you can click the three dots near the upper-right to temporarily redisplay the tools, or click Always Show Reading Toolbar to toggle them back on.

To exit Read Mode, you can click the Print Layout view button on the Status bar, or press Esc. In some cases, when Always Show Reading Toolbar is not toggled on, you may need to press Esc twice to exit Read Mode.

Web Layout is designed for composing and reviewing documents that will be viewed online rather than printed. Hence, information such as page and section numbers is excluded from the status bar. If the document contains hyperlinks, they are displayed underlined by default. Background colors, pictures, and textures are also displayed.

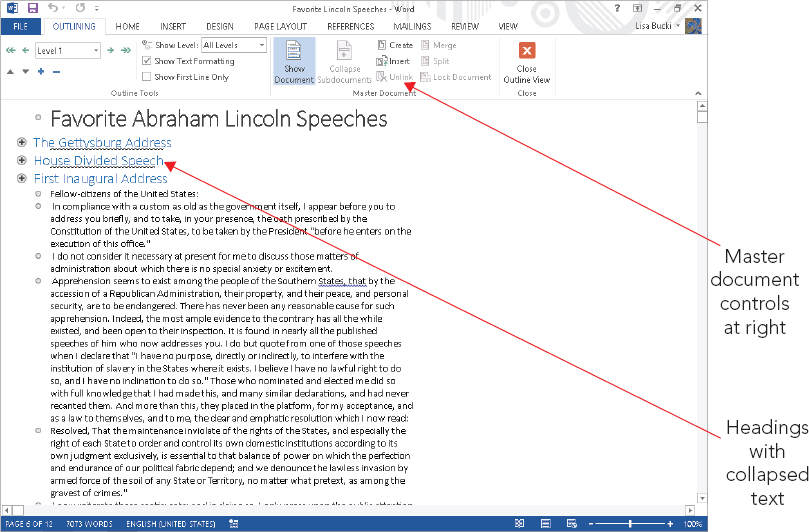

The final distinct Word view is Outline (View ⇒ Views ⇒ Outline). Outlining is one of Word’s most powerful and least-used tools for writing and organizing your documents. Using Word’s Heading styles is one way to take advantage of this tremendous resource. Heading levels one through nine are available through styles named Heading 1 through Heading 9. You don’t need to use all nine levels — most users find that the first three or four are adequate for most structured documents. If your document is organized with the built-in heading levels, then a wonderful world of document organization is at your fingertips.

As an outline manager, this view can be used on any document with heading styles that are tied to outline levels. (If you don’t want to use Word’s built-in Heading styles, you can use other styles and assign them to different outline levels. Additionally, you can build a document from the headings found in Outline view. You can expand and collapse text to focus on different sections of the document as you work, or to see an overview of how the topics in your document are flowing. Click Outlining ⇒ Close ⇒ Close Outline View to finish working with outlining.

As suggested by the title of this section, Outline view has a split personality, of sorts. Outline view’s other personality includes the Master Document tools. As shown in Figure 4.21, if you click Show Document in the Master Document group of the Outlining Ribbon tab, additional tools appear.

FIGURE 4.21 Click Show Document in the Master Document group to display the Master Document tools.

Word 2013 includes a new Resume Reading feature. When you reopen a document you were previously editing, and the insertion point was on a page beyond page 1 when you closed the file, a prompt appears at the right side of the screen asking if you want to go back to the page you were last working on, as shown in Figure 4.22. Click the pop-up to go to the specified location. If you don’t initially click the message, it shrinks to a smaller pop-up with a bookmark icon on it. You can move the mouse over it or click it to redisplay the message, and then click to jump to the later spot in the document. Scrolling the document makes the pop-up disappear.

FIGURE 4.22 Click the pop-up to return to the page you were last working on before you close the document.

Another sometimes-overlooked tool is the ruler. It’s useful for aligning and positioning text and other objects, which you’ll learn about in later chapters. The ruler toggles on and off via the View ⇒ Show ⇒ Ruler check box.

Choose View ⇒ Window ⇒ Split to divide the document window into two equal panes.

This feature comes in handy when you need to look at a table or a figure on one page of a document while you write about it on another page.

As another example, you might want to have one view of your document in one pane while using another view in the other, as shown in Figure 4.23. When viewing a document in two split panes, note that the status bar reflects the status of the currently active pane. Not only can you display different views in multiple panes, but you can display them at different zoom levels as well.

FIGURE 4.23 Split panes can display different views.

You can remove the split by dragging it up or down to the top or bottom of the screen, leaving the desired view in place, or double-clicking anywhere on the split line. Alternatively, Choose View ⇒ Window ⇒ Remove Split.

In this chapter you’ve learned basic yet essential skills for creating and working with document files, using file formats, navigating a document, and more. Putting it all together, you should now have no problem doing the following: