Chapter Fourteen

Source Code

“Microcomputers catch on fast.”

That was the headline in an issue of BusinessWeek I bought the summer of 1976, about a year after we signed our contract with MITS. I liked the story because it wasn’t in the trade press or a computer hobbyist newsletter, the typical publications that followed our corner of the computer industry. I figured BusinessWeek readers were investors and executives—mostly people who had yet to own a computer themselves but might be inclined to buy one if they were easier to use.

With a blue ballpoint pen, I highlighted what I saw as the key paragraph: “Already, the home computer industry is beginning to look like a miniature version of the mainframe computer business—down to the dominance of one competitor. The IBM of home computers is MITS Inc., founded seven years ago by engineer H. Edward Roberts in the garage of his Albuquerque (N.M.) home.” The story noted that MITS had sold eight thousand Altair computers and brought in $3.5 million of revenue the previous year. There were competitors, the story noted, but the Altair’s early lead made it the industry standard.

The article brought a rush of phone calls into MITS from as far away as South Africa; people wanted to connect with the hot company in the story, either by becoming distributors, opening computer shops, or working as consultants helping introduce the Altair to business customers. MITS employees were gushing over the article and hoped it would lead to even more sophisticated applications of their machine.

As I read, I thought, Even if MITS is the IBM of the moment, that isn’t going to last. One reason: if IBM ever decided to make a personal computer, there’s a good chance it would replace MITS as the IBM of the moment. I knew that Ed Roberts was also worried that major electronics companies would push their way into the fray. In Ed’s eyes, the scariest of those companies was Texas Instruments. In the early 1970s MITS had pioneered programmable kit calculators, which are used by engineers and scientists. Once that market reached a certain size, big companies, led by Texas Instruments, swooped in with assembled low-priced alternatives and nearly killed off MITS. Ed deeply feared a repeat with personal computers.

It was clear to all of us that Ed was growing tired of running MITS. Less than two years after unveiling the Altair, his work life was an endless headache of customer calls, complaints from Altair dealers, and the day-to-day hassle of a company that had swelled from a handful of people to well over two hundred employees. On any given day, a frustrated employee would harangue him because a colleague got paid a few more cents an hour. At least once, he fired someone but felt so bad about it, he soon rehired them. Ed had a soft spot that didn’t always square with his often gruff exterior.

It worried me that we were still so reliant on MITS. Royalties from licenses of 8080 BASIC for the Altair were still our largest source of revenue. Licenses of our source code for that version of BASIC were picking up. Around that time, we landed General Electric, which gave us $50,000 for unlimited use of the 8080 BASIC source code. Following the NCR deal, a bunch of other smart terminal vendors had contacted us. I visited one of them, Applied Digital Data Systems, on Long Island. I flew into New York’s JFK intending to drive a rental car to ADDS in Hauppauge, about an hour away. My plans were thwarted by a rental agent who informed me that he couldn’t rent me a car: I was too young. Someone from ADDS collected me from the airport. It was an embarrassing start to the relationship. Still, they were interested, and so began a protracted back-and-forth as we worked out a deal.

Of course, since MITS held worldwide rights to 8080 BASIC, any time we found a customer for the source code, the contract would have to go through MITS. If we signed a deal, we then had to split the revenues with them. Gradually, that summer, we began to try to wean ourselves off MITS. We started the search for our own office and began work on products that could draw in new customers.

The job of finding those new customers mostly fell to Ric, who had taken on the role of general manager. In the months since we had agreed to a three-way partnership, Ric had experienced a change of heart. To be a partner meant he’d have to focus entirely on Micro-Soft; he wanted time to branch out and enjoy a well-rounded life. He went to church, lifted weights at the gym, took off time to visit friends in Los Angeles. Though Ric had come out to Paul and me years earlier, it was in Albuquerque that he fully embraced who he was. In a nod to that new life, he bought a Corvette with a personalized plate that read “YES I AM,” in case anyone wondered. He blossomed socially and found his first love.

After Ric had opted out of the partnership, Paul and I agreed that we would continue to split ownership of Micro-Soft sixty-forty. Officially we each used the title “senior partner,” though as a parody of big-company business types, we adopted grandiose titles among ourselves: I was “the President,” and he was “the Veep.” As general manager, Ric handled marketing and most of the day-to-day work, from dealing with MITS to depositing checks and finding our office space. He was meticulous, recording every interaction in a notebook titled “The Micro Soft Journal.” Today it’s an artifact of what it was like doing business in the 1970s: typed letters and phone call after phone call to company after company, hoping to reach someone who might be interested in buying our software. A sample:

Saturday, July 24:

2:45 Try Steve Jobs. Give his mom message.

Tuesday, July 27:

10:55 Try Steve Jobs. Busy.

11:15 Steve Jobs calls. Was very rude.

11:30 Try Peddle again. Must talk to him.

Peddle was Chuck Peddle, an engineer at MOS Technology, the maker of the 6502 chip that Steve Wozniak had used in the Apple I. A few years earlier, Peddle had left Motorola with several other engineers to join MOS Technology, where they created the 6502. The chip was similar to the Motorola 6800 microprocessor. We had developed a version of BASIC for the Motorola chip, so Ric had started to write a version for the 6502. But we needed a customer. All through the summer and early fall, Ric filled his journal with his attempts to reach the company by phone: 12:55 Try Peddle again; called Peddle at MOS Technology. Out on vacation. Call Peddle. Busy. Steve Jobs, meanwhile, told Ric that Apple had a version of BASIC that his partner Wozniak designed, and that if it needed another one, Wozniak would write it, not Micro-Soft. However Steve delivered that news, I guess Ric found it off-putting.

The popularity of BASIC gave Micro-Soft its start, and we would continue to adapt the language to different microprocessors as Ric was doing with the 6502. And yet BASIC, for all its ease of use and popularity with hobbyists, wasn’t the language that more serious computer buyers wanted. Scientists and academics used FORTRAN; businesses, COBOL. Meanwhile, FOCAL was a BASIC alternative popular among the many users of DEC minicomputers. In a push to expand, we got to work on versions of all three. We also started pitching Paul’s development tools to customers. Early on, Paul and I had envisioned Micro-Soft would offer a broad array of software products—the software factory idea. We weren’t anywhere near that yet, but building an array of languages and development tools was a step toward that future.

To support the development of new products, in late summer we started hiring our first full-time employees from outside our Lakeside circle, including Steve Wood, who had just finished his master’s degree in electrical engineering at Stanford, and his wife, Marla Wood. Until that point, we were a band of friends whose futures didn’t worry me. If everything blew up, I was confident that we’d head off in our various directions and be fine. But now we were hiring people we didn’t know and asking them to move to New Mexico and cast their lot with us, an eighteen-month-old company with an unclear future. It was a bit daunting. To me, those early hires made Micro-Soft feel like a real company.

I was in Seattle that summer to write what I thought would be the product for our future, a programming language called APL, which was short for, well, A Programming Language. IBM, which had developed the original version in the early 1960s, continued to champion it in the 1970s and offered it on a variety of computers. The language was highly regarded by serious programmers, many of whom thought its popularity was poised to grow. If we could come up with our own version, I figured we could ride that wave and expand into the business market beyond the hobbyist roots of BASIC.

APL also appealed to me as a coder. It has very concise syntax, allowing you to execute in just a few statements what would take many lines of code in other languages. That made writing a version for a personal computer a tricky puzzle of compressing great complexity into a small package. I labored day and night to get it right, working off a portable terminal I had set up in my bedroom and paying my parents for the dial-up phone charges. Libby, then age twelve, would stand in my doorway wondering what her crazy brother was up to, glued to his computer terminal all day. On breaks she’d battle me in Ping-Pong. (I never did manage to crack APL, but my Ping-Pong game improved.)

That summer would turn out to be the last time I lived in my parents’ house. When I think about it now, I have much greater appreciation for the role my family played during that early period of Micro-Soft. As proudly independent as I imagined myself, in truth my family supported me in ways both practical and emotional. Throughout the year I regularly retreated to Gami’s place on Hood Canal for much-needed periods of reflection, and that summer was no exception. My father was always at the ready to help me work out some legal issue. Kristi, meanwhile, now twenty-two and thriving at Deloitte, was handling Micro-Soft’s taxes.

To my parents, it must have seemed that I was finally getting organized in my father’s sense of the word. I had my own business and, while I had taken a semester off from college, I was returning in the fall for what would be the second semester of my junior year. They were happy with my plan and understood that I found college intellectually fulfilling in a way that was distinctly different from Micro-Soft. I signed up for a course in British history during the Industrial Revolution and used my applied math wild card to talk my way into ECON 2010, a graduate-level economic theory class. There was another undergraduate in the class, a math major named Steve Ballmer.

The previous year, a Currier House friend had suggested that I meet a guy who lived down the hall. “Steve’s a lot like you,” he said. By then I could instantly recognize other people—Boomer and Kent were prime examples—who emitted my kind of excess energy. Steve Ballmer had it beyond anyone I had ever known. Most of the male Currier residents were nerdy math-science types who kept to their own and whose social lives revolved around playing Pong or poker in the dorm basement. Steve didn’t fit that model. He had an unusual combination of brains and physicality and was effortlessly social. He was way more active on campus than anyone I knew, overseeing advertising at The Harvard Crimson, serving as the president of the literary magazine, and managing the football team.

I went to one game that fall and from the stands watched Steve expend as much energy pacing and bouncing on the sidelines as any Harvard player deployed on the field. Every particle of his being was trained on that team. You could tell that he really cared about his role as manager. It was hard not to get caught up in his exuberance. Steve expanded my social circle, and through him I was nominated for membership in the Fox Club, a male-only club with black-tie parties, secret handshakes, and other archaic rules and rituals that I would normally have avoided. But since Steve was a member, I agreed to be considered, and was accepted.

As it turned out, we didn’t spend much time in ECON 2010 together; given my continued approach to skipping classes until the final and Steve’s packed schedule, neither of us attended the three hours of weekly lectures. We agreed we’d risk it all on the final. Late at night in the dorm, however, Steve and I had long talks about our life goals reminiscent of my conversations with Kent. We hashed out the benefits of working in government versus for a company, and which of those options would enable us to do more to improve society and have a greater impact on the world. He typically argued on the side of a big role in government. Not surprisingly, I took the side of corporate interests. It was, after all, the job that was on my mind most of the time.

As the semester progressed, I began to feel extremely conflicted about Micro-Soft. Up to that point, the company seemed manageable from afar, particularly with Ric overseeing the day-to-day. But as we were growing, so did the complexity of the business details. Often when I’d check in with Paul or Ric, I’d hear about some new issue that I thought wasn’t being handled. The more I learned about the GE deal, for instance, the more I came to believe we had underbid them for the work we promised. Ric wasn’t tracking the money for employee business trips, and we were way over budget on travel; we were owed $10,000 from NCR, but neither Paul nor Ric knew when it was expected. One of our biggest problems was MITS, which hadn’t paid royalties it owed us related to Altairs that included extra memory. Since most of our revenue came from MITS, we needed every bit of it to keep Micro-Soft going until other sources panned out.

I made my frustration clear in early November. After a rare night of partying with Steve and my new social club friends, I went back to my dorm and typed a letter to Paul and Ric, warning them that “I went out drinking for the first time this semester tonight so I might not be too coherent, but I decided to write this tonight so I’m going to.”

Reading the letter now is a reminder that even as our company was taking off, we were still working on the traffic venture and helping Lakeside with its schedule. I began with a page of technical directives related to those two projects. But the focus was Micro-Soft, and all the things that were falling through the cracks: travel expenses, employee oversight, customer follow-up, and contract negotiations. I groused that they still hadn’t lined up a company credit card. Paying $800 in some kind of penalty was another beef, as was the ongoing issue of getting MITS to pay our royalites. I wrote: “Spending $14,000 since I’ve left and not thinking about cash flow or taking care of the memory royalty is the way to send us down the tube.”

I closed the letter: “For all that talk about hard work and long hours, it’s clear that you guys haven’t talked about Microsoft together or even thought about it individually, at least not near enough. As far as ‘putting out your last measure’ the commitment just isn’t being met. Your friend, Bill.”

The warning about the drinking aside, my tone wasn’t unusual for the time. Of the three of us, I had always been the taskmaster, the one who incessantly worried about losing our lead, and fearing that if we weren’t careful, we’d be sunk. We’d watched C-Cubed go from promising start-up to having creditors drag the furniture away eighteen months later. And in just the past year, we were witnessing the growing troubles at MITS, which had the lead but seemed to lack the management rigor to maintain it. We were a young company figuring out all the functions of business: legal, human resources, tax, contracts, budgets, and finance. We knew the core job of developing software. I worried we weren’t learning everything else fast enough.

A couple of weeks later I was in Albuquerque for ten days over Thanksgiving break to work through some of the issues in my tough-love letter. We had just moved into our first true headquarters: rented office space on the eighth floor of a new ten-story building, Two Park Central Tower. It was one of the tallest buildings around, offering an incredible view of the sunsets over downtown Albuquerque and rainstorms far off in the desert. The space had a reception area and four separate offices, and more that we could rent as we expanded. (Around that time we officially incorporated Microsoft in New Mexico—without the hyphen.)

My trip coincided with Paul’s decision to quit MITS and dedicate himself exclusively to Microsoft. I don’t remember if my concerns about our company factored into his decision; I don’t know how pressured he felt by me. I do know that Paul was tired of MITS. As Ed’s stress grew, so did the tension between him and Paul. At one point they had a blowup over Ed’s insistence that Paul ship software that wasn’t ready; Paul gave notice soon after. Whatever his reasons for leaving, it was good news for us. He would be able to spend more time guiding our new employees on the technical development of FORTRAN and other products.

I reviewed the cash flow with Paul and Ric and worked through the finances of expanding our office space as we hired more people. We were getting a lot of inquiries for our 8080 BASIC and were trying to nail down contracts from companies including Delta Data, Lexar, Intel, and ADDS, the smart terminal maker I had visited on Long Island. Increasingly, though, Ed didn’t sign.

That was troubling. But we hoped to quickly find new revenue from other products. One was the 6502 BASIC that Ric was writing. In late August a company called Commodore International announced that it had bought MOS Technology. Commodore had been a leading maker of calculators that, like MITS, got trampled by Texas Instruments. But also like MITS, it had the expertise to design and build a personal computer. And now Commodore had the chip for it.

One afternoon just before Thanksgiving, Ric called Chuck Peddle, his contact at MOS Technology, now part of Commodore. After months of missed calls and messages, Peddle said that Commodore was interested in our BASIC and that our price was agreeable to them. It was great news. (Within a few weeks Paul would flag a story in the EE Times: Commodore planned to build a general-purpose computer based on the 6502. We needed to finish the BASIC for it as soon as possible.)

A little over an hour after Ric spoke with Peddle, we got a call from a software manager at Texas Instruments. The TI manager informed Ric that his company was working on a computer built around one of its own chips. He wanted to see documentation on our BASIC and on our company. He said they would have to convince TI’s management to go with us, but TI’s interest alone was a huge breakthrough. Aside from IBM or DEC, there was no other company whose entry into personal computers had been more highly anticipated. TI had a brand name, engineering prowess, and marketing skill. It was also the company that Ed Roberts had long feared. TI’s deep pockets and aggressive pricing had almost sent MITS to the grave once, and it could easily do so again.

I was back at school when we heard rumors that a group of men in pin-striped suits had been spending time at MITS. MITS wasn’t a natural habitat for suits. They stuck out. Eventually we learned that the men were from a company named Pertec. Pertec? I had never heard of it. I went to Widener Library (yes, this was before you could search for things like this on the internet) and found a write-up. Pertec, or Peripheral Equipment Corporation, was a publicly traded maker of disk drives and other storage devices for large computers. It was based in California, and it was big: over a thousand employees and nearly a hundred million dollars in annual revenue.

Pertec made an offer in early December to buy MITS for $6 million. If the deal went through, Ed Roberts would be rewarded for his innovative idea to build a microcomputer. And with funding from a parent company, maybe MITS could stave off Texas Instruments and any other interloper that wanted to steal the computer market from it.

Soon after Pertec began courting MITS, everything Microsoft-related stopped completely. Royalty payments stopped; licensing deals stopped. Ed had already told us that he refused to sell our BASIC to any company he thought would compete with MITS. By late 1976, his definition of competitor had widened to include the entire industry.

Over Christmas break in Seattle, I got a letter from Ric. Another change of heart: He was going to leave Microsoft. After further soul searching, he had reached the conclusion that he wanted to live in Los Angeles, where he thought he could build a vibrant social life. There was also a small but established software company in L.A. that wanted to hire him.

I felt abandoned. When we spoke next, I accused him of misleading me the prior spring when he assured me of his commitment to Microsoft. He countered that he had never promised to stay long. We went back and forth about money, and all the work we still had ahead of us. Eventually we calmed down. I asked if he could stay until March to finish the 6502 BASIC for Commodore. I said we’d pay for the work he was doing plus the salary that his new company promised until he left in March. He agreed. He then flew off to the Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, where our new partner, Commodore, debuted the Commodore PET 2001, an all-in-one computer with a built-in monitor, a keyboard, and a cassette tape player (for storing data). It came in a molded-plastic case and looked different from any previous personal computer, more like something you’d find in a home than on a hobbyist’s workbench. That was the point.

I was visiting my grandmother on Hood Canal over the holiday break and stepped out one night for a long walk. I vividly remember making my way down the two-lane Route 106, which snakes along the southern strip of the canal, thinking through the problems with MITS and the larger question of how to manage Microsoft over the coming year. MITS and its suitor Pertec were making no effort to sell our software, and they were blocking deals even as more and more companies were soliciting us. It felt like the industry was finally starting to take off and there was no way we were going to get left behind, I told myself. Wrapped up in this was my sense that it was getting harder and harder to live life as a college student with a sideline software company.

Paul and I were totally aligned on the vision to create the leading PC software maker. That goal was like a prize we could glimpse on the other side of a river. But it was clear to me by the end of 1976 that the ambition to be the first to get there—to be the fastest to build the best bridge to the other side—was stronger in me than it was in him.

Like one of those watertight hatches on a submarine, I could shut out the rest of the world. Driven by the sense of responsibility I felt for Microsoft, I had closed the hatch door and locked the wheel. No girlfriend, no hobbies. My social life centered around Paul, Ric, and the people we worked with. It was the one way I knew to stay ahead. And I expected similar dedication from the others. We had this huge opportunity in front of us. Why wouldn’t you work eighty hours a week in pursuit of it? Yes, it was exhausting, but it was also exhilarating.

Despite my self-confidence and proclivity to figure out things on my own, I was coming to the realization that I needed the kind of help that Paul wasn’t prepared to give. He was a partner in some of the most important ways: we shared a vision for the company, and we worked well together when it came to questions of technology and who to hire to build software. But none of that would matter if the business foundation wasn’t secure. Keeping Microsoft going was a lonely job. I needed a twenty-four-hour-a-day business partner, a peer who would hash out and argue through big decisions with me, someone who would pore over scribbled lists of which customers might or might not pay and discuss what our bank account would look like as a result. Shouldering a hundred things like that every week on my own was a burden that at that time I felt should be acknowledged by an even bigger stake in what we were building.

On that walk along Hood Canal, I decided that if I left school to be at Microsoft full-time, I would tell Paul I wanted an even bigger share of the company. I mulled both decisions after I returned to Harvard in January for the reading period ahead of finals. Steve Ballmer and I had stayed true to our plan to skip the ECON 2010 lectures. We spent the reading period teaching each other the material, working nearly nonstop trying to cram a semester’s worth of knowledge into our brains. We were triumphant when we passed the one-page final.

On January 15 I wrote Harvard: “A friend and I have a partnership, Microsoft, which does consulting relating to microprocessor software. The new obligations we have just taken on require that I devote my full-time efforts to working at Microsoft.” I said that I planned to return to school in the fall and graduate in June 1978.

My parents knew it would be pointless to tell me to stay in school. I was too independent. But my mom sometimes used subtle means to try to convince me. At some point, during either that year or the previous one, she arranged for me to meet a prominent Seattle businessman, Sam Stroum, who had built a big chain of electronics stores before acquiring and expanding a major regional auto-parts chain. He was also very active in nonprofits, a pillar of Seattle society. My mom got to know him through her work with the United Way. Over lunch I explained Microsoft and my plan to make software for every microprocessor we could and how that market would grow, and our company along with it. Whatever hope my mother may have had for that lunch, I don’t think it was achieved. Instead of telling me to stay the course at Harvard, Sam was excited by what I was doing. His enthusiasm might have assuaged my mom’s concerns a little but not fully. (Sam liked to joke years later that he regretted not writing me a check for part of the company at that lunch.)

“If Microsoft doesn’t work out, I’ll go back to school,” I assured my parents.

Back in Albuquerque, I told Paul I wanted to make the split sixty-four–thirty-six. He pushed back. We argued, but eventually he gave in. I feel bad now that I pushed him, but at the time I felt that split accurately reflected the commitment Microsoft needed from each of us. We signed an agreement in early February and made it official. (A little over three years later, that slice of the company would come up again as I was trying to convince Steve Ballmer to quit business school to join Microsoft. As an incentive, I included that extra 4 percent as part of his package. He joined in 1980 and became the twenty-four-hour-a-day partner I needed.)

Despite our tension over ownership of the company and our perennial spats, Paul and I had a strong bond. We had already shared an incredible journey; now we were building something unique. And having a pretty good time at it too.

We had also figured out one way to help keep our friendship intact: don’t live together. While I was in Boston, Paul had left our Portals apartment and rented a three-bedroom house in the suburbs with Ric and Marc McDonald. When I returned to Albuquerque, I moved into an apartment with Chris Larson. Chris had been coming and going from Albuquerque to work summers with us. Now in his senior year at Lakeside, he convinced his parents to let him join us at Microsoft, taking off a semester as I had done for the TRW job.

Living apart from Paul meant I no longer had access to the Death Trap Monza, so I bought my own car, a 1971 Porsche 911. Though used, it was a major expense for me, but I had always coveted Porsches and loved the raspy whistle sound of their six-cylinder engines. Still, even today I’m a little self-conscious admitting that I bought it.

Driving that Porsche became my escape, my time for thinking through the company’s issues as I whipped around the Sandia Mountain roads well over the speed limit. Often Chris joined me. The previous year we had found a nice smooth road that wound up and up into the mountains, leading to a cement plant. After I got the Porsche, we took regular high-speed drives on Cement Plant Road, as we called it. Late one night we stopped at the plant and discovered they kept a couple of bulldozers with keys in the ignition. Chris and I spent more than a few nights at the top of that cement plant road teaching ourselves how to drive the massive earth movers.

Racing around in my car at night with Chris, seeing movies, and hanging out with Paul and the rest of the Microsoft team was the extent of my non-work life in Albuquerque. Steve and Marla Wood, who as the only married couple in the group offered a dose of domesticity, would often host us for dinner, or we’d head to Paul’s house to watch shows on his projection TV. We found ourselves obsessed with The Pallisers, a BBC production of Anthony Trollope’s Palliser novels. We’d meet after work, settle on the couch and carpet, and get thoroughly sucked into twenty-two hours of the dukes and duchesses, love triangles, and money troubles of Victorian England.

As spring arrived in 1977, it was increasingly clear to me that MITS and Pertec had no intention of paying us back royalties or sublicensing 8080 BASIC to any other companies. In their eyes, they owned the software and we were a nuisance, a small wrench in their plan to buy the leading personal computer maker. Pertec had structured the acquisition as a merger between MITS and a new Pertec subsidiary created for the occasion. We thought it had done so in part to ensure that the rights MITS held to our BASIC would become part of the deal. Yet now I wondered if they had even read our contract. We didn’t transfer ownership of the software to MITS. We licensed it to them. And MITS was obligated by the contract to make its best efforts to sublicense the software to other companies.

It all went back to the spring of 1975 and the weeks after Paul, Monte, and I wrote the 4K BASIC and delivered it to MITS. This is the period during which Ed had delayed signing the contract and I holed up in Seattle until he did.

In negotiating that contract, Ed had insisted that we give MITS a worldwide exclusive license to 8080 BASIC for ten years. I didn’t want to agree to that, but I wanted to close the deal. And I wanted to make a good impression on our new partner.

I asked my dad if he could help us find a lawyer in New Mexico. That led him to a trial lawyer at his old firm, whose nephew, a man named Paull Mines, worked as an attorney in Albuquerque. I called Mines, and his firm, Poole, Tinnin & Martin, helped us draft the contract. In 1975, a contract to license software was still a very new thing. I’m sure this was probably the first time the firm had worked on one. They did a good job, and I made one important inclusion.

I don’t know when I first heard the legal term “best efforts,” but a good guess would be at the dinner table as my parents discussed my father’s work. When a company agrees to make its best efforts, it agrees to do everything in its power to make good on whatever is stipulated in a contract. However the phrase had first lodged in my brain, it surfaced in those contract negotiations with MITS. I said we’d agree to the exclusive license if MITS agreed to make “best efforts” to license our source code. The MITS lawyers pushed back, saying that nobody agreed to best efforts. They’d consider “reasonable efforts,” but I wouldn’t agree. Best efforts it was.

Now, I went back and reread that clause again and again. Page 2, clause 5: “Company Effort. The Company [MITS] agrees to use its best efforts to license, promote, and commercialize the PROGRAM. The Company’s failure to use its best efforts as aforesaid shall constitute sufficient grounds and reason for termination of this agreement by Licensors.”

It all seemed so clear to me.

Over the past year I had become friends with Eddie Currie, general manager of MITS and our partner in trying to market BASIC to outside companies. Eddie had grown up in the same Florida community as Ed Roberts; the two had known each other since elementary school. But where Ed could be strident, Eddie was even-keeled and acted as the calm middleman between MITS and Microsoft. Eddie seemed very invested in helping both companies succeed. Together we pitched 8080 BASIC to outside companies, and when we landed one, Eddie worked with Ed Roberts to get the contract signed.

In his capacity as middleman, Eddie Currie had encouraged me several times to meet with the Pertec lawyers to see if we could work through the disagreement. I felt intimidated and hoped that we could instead hash out the whole thing directly with Ed. I also knew that Eddie was trying to persuade Ed to hold out for another suitor who might offer a higher price. When it was clear that wasn’t going to happen, I agreed to meet with Pertec. Walking into a conference room at MITS, I found three Pertec lawyers. They asked Eddie to wait outside while we talked.

The lawyers told me that when Pertec closed its deal with MITS, it would take over the licensing agreement, and the contract would be “assigned” to Pertec. That wasn’t going to happen, I said. Paul and I would have to agree to sign it over to Pertec, and we weren’t going to do that. Page 7: “this agreement may not be assigned without the express written consent of the parties.” Had they read that? None of that mattered, they responded.

I felt myself growing more frustrated. “You guys are totally wrong,” I snapped. “The BASIC interpreter is not yours!”

The rest of the meeting devolved into a shouting match between me and the lawyers. At one point we reached a standstill, the argument simmering, when Eddie knocked on the door. There was a phone call for me. It was Paul. He said that Eddie had heard us yelling and had called him, thinking Paul should come and yank me out of the meeting. Should he run over? “No,” I told Paul, in a voice loud enough for everyone to hear. “These guys are trying to screw us over, but I’ve got it under control.” I hung up and went back to the lawyers. During our resumed argument, the lead Pertec lawyer laid out in stark terms what he would do if I continued to insist on holding on to our software and not agree to his terms. He “would destroy Microsoft’s reputation.” He informed me that I would be “personally liable for criminal fraud, and I will sue you for your entire personal wealth.” Later, Eddie said he felt bad about arranging the meeting and that he thought the lawyers had ambushed me.

I called my father that night. He was appalled that the lawyers had met with just me, without a lawyer to represent Microsoft. The next day I visited Paull Mines. He reviewed our contract and confirmed we were in the right. The best-efforts clause was binding. And if it wasn’t clear already, MITS was going out of its way to not make its best efforts. Within weeks, Ed Roberts sent ADDS a letter stating that MITS had determined that it should discontinue any efforts to license the BASIC software. He said Bill Gates might try to restart those discussions. “To avoid any embarrassment to any of us, you should be aware that MITS holds the exclusive rights to the BASIC software programs developed by Mr. Gates and his partners and that any commitments regarding the rights to the BASIC program, or any modified versions or portions of it, by anyone other than MITS personnel are not authorized.”

In April, amid the standoff, I flew to San Francisco to attend the First West Coast Computer Faire. Walking into the Civic Auditorium, I was astounded. Thousands of people—all told, just under thirteen thousand attendees over two days—were pushing their way through the rows of booths of companies like ours, Processor Technology, IMS Associates, and Commodore, showing its PET. To a company, all focused on personal computers. In that moment, I felt that the industry had arrived.

On the first day I was talking to a crowd of people about our Extended BASIC when out of the corner of my eye I noticed a handsome guy around my age with long black hair, a tightly cropped beard, and a three-piece suit. He was a few booths away, holding court with his own gaggle of people. Even from a distance I could tell he had a certain aura about him. I said to myself, “Who is that guy?” That was the day I met Steve Jobs.

Apple, though smaller than many of the other companies, stood out. Even then the trademark design sense that would make Apple—and Jobs—so iconic in coming decades was on display. At the show they launched the Apple II, which in its sleek beige case looked more like a polished piece of consumer electronics than a personal computer. The company had decorated their booth with fancy Plexiglas signs, including an elegant logo of a bitten apple they’d commissioned from a marketing firm. They had a spot at the entrance to the event hall and were using a projector to cast the Apple II’s color graphics onto a giant screen, ensuring that anyone walking in would immediately see their logo, signage, and new computer. “The Apple guys are getting a lot of attention,” Paul said to me.

That first encounter in the spring of 1977 would mark the start of a long relationship between Steve Jobs and me, marked by cooperation and rivalry. At the Computer Faire, though, I mostly spoke with Steve Wozniak, who had designed and built the Apple II. Like Commodore’s PET, the Apple II used MOS Technology’s 6502 chip.

Wozniak at the time was one of a rare breed in our industry, someone who deeply understood both hardware and software. The BASIC he’d written, however, had a fundamental problem: it was a simple form of the language and could handle only integers—no floating-point math, which meant no decimal points or scientific notation, both of which are essential for any sophisticated software program. Apple needed a better BASIC and Wozniak knew it. Having already written a 6502 BASIC for Commodore, we had a head start on writing one for Apple. At the convention I talked up our work and emphasized that it would be cheaper and faster to license our software than to try to write it himself. I left San Francisco optimistic that we’d sign a deal.

Days later, back in Albuquerque, I got word from Texas Instruments that it had chosen us to write a version of BASIC for the personal computer it was designing. The company said it had envisioned the computer as an appliance for families to manage home finances, play games, and write school reports. I hoped this would be the computer that would break out into the mass market. Not just a few thousand customers but maybe tens of thousands.

We had beaten out at least two other bidders for the work. Getting the deal was a big confidence boost. I had wanted to charge TI a flat licensing fee of $100,000, but I chickened out. Fearful that the company would balk at six figures, I asked for $90,000, which was still the biggest deal we had signed aside from NCR, which we had to split with MITS. When TI visited Microsoft for the first time, our new office manager had to run out to buy extra chairs so there’d be a place for everyone to sit.

TI was using its own processor, which meant writing a new version of BASIC from scratch. That would be months of work for at least two people. Monte was again willing to spend the summer in Albuquerque, but with Ric leaving, we needed to hire another coder. After we signed the deal at TI, I called Bob Greenberg, who had been in a few math classes with me at Harvard and who I knew was weighing job offers at the time. “I’m your man,” he told me.

Whether we had the cash to pay him was another question. MITS had come through with a small amount of royalties but had refused to pony up the full amount that it owed us, then over $100,000.

Paul and I had had enough. In late April, working with our lawyer Paull Mines, we sent Ed Roberts a two-page letter listing the ways MITS had breached our contract, including the unpaid back royalties and its refusal to use its best efforts to license 8080 BASIC to companies such as ADDS and Delta Data. If MITS didn’t meet our conditions to pay the royalites and resume licensing our software within ten days, we wrote, we would terminate the contract.

The response was swift: within days Pertec and MITS filed for a restraining order to prevent us from licensing 8080 BASIC.

In June, as stipulated by our contract with MITS, our dispute moved to arbitration. Initially I was worried about our lawyer. Paull Mines had a manner that could make him appear disorganized as well as a tendency to lose his train of thought—a somewhat scattered demeanor that only bolstered what I perceived as the opposing lawyers’ misplaced confidence. They seemed smug, convinced that their victory was inevitable. In fact, Mines was very sharp and thorough. Every night he had us in his office preparing for the next day, poring through the details of our contracts and every interaction with every company that had expressed an interest in BASIC.

The hearings with the arbitrator lasted about ten days. I sat in on all the testimony as Microsoft’s representative. Eddie Currie played the same role for the MITS side. Ric, Paul, and I were deposed as well as Ed Roberts, Eddie, and various other people from the companies. The stakes for Microsoft aside, I found the proceedings fascinating. In full Kent fashion, I showed up every day with my own monstrosity of a briefcase stuffed with every document I would ever need. I’d rustle around in the briefcase and yank out paper after paper—to find a reference but also for the show of it. I was hoping for an effect opposite of the one I’d sought by not carrying books in high school: Look at all those papers! They must be super-prepared!

Some nights after the hearing ended, Paul, Eddie, and I would go out to dinner and compare notes, speculating about whose side the arbitrator seemed more favorably disposed toward on a given day. The arbitrator continually struggled to grasp the basics of the technology at the center of the dispute. We tried to help him by dubbing our 8080 BASIC source code “the Grand Source,” to differentiate it from the other versions not covered by the contract.

We had called a witness from ADDS, hoping to prove that the terminal maker wanted to license BASIC but had been blocked by MITS. At dinner the night before the ADDS testimony, I told Eddie that the code name for the ADDS product was “Centurion.” I didn’t realize that Eddie would share that tidbit with anyone else. I also didn’t realize that I got the name wrong.

Both facts hit me the next day when the Pertec lawyer confronted the ADDS witness about the secret project. “Tell us about Centurion,” the lawyer said, seeming very sure that he was about to expose some gaping hole in in our defense.

“I have no idea,” the ADDS guy answered.

“You must know about Centurion,” the lawyer fired back, to which the witness answered, “I guess I do. I think it’s a Roman legion or soldiers or something like that.”

I don’t remember what the accurate code name was. Eddie surely assumed I had intentionally misled him. I wish I had been that smart. From then on, I learned to be more careful.

Our central challenge was to convince the arbitrator that (1) many companies wanted to license 8080 BASIC, and (2) Pertec/MITS was blocking those licenses when they were contractually obligated to make their best efforts at facilitating them. Fortunately, Ric had detailed our communication with all these companies over the past year in his Microsoft journal. That record helped us make the case that the world wanted what we made.

The hearings ended in late June. Then we waited. And waited.

With our money from MITS on hold, Microsoft needed cash. In one of my many phone calls with my parents that summer, I broached the subject that I wanted to avoid: I might need to borrow some money to keep us going. At that point we owed Paull Mines about $30,000, we had employees to pay, and our cash flow had slowed to a trickle. Paul was worried enough one night to tell me we should consider settling with MITS. Both Paull Mines and my father had assured me that we would likely win the arbitration, I told him. We should trust them.

The day after our hearings ended, Paul and I took our Microsoft employees for a lunch of prime rib and salad bar at a chain called Big Valley Ranch, which for us was a fancy choice. There were about seven of us, including Ric, who was leaving the company the next day for good. What do the President and the Veep do when they’re worried and want to boost morale? Feed your employees lunch and talk frankly about their worries. It was a moment to communicate the obvious: though we were confident that we’d win the arbitration, it wasn’t guaranteed.

That afternoon, I paid Ric what we owed him. The next day, July 1, he came by the office to see us before heading to his new job and life in California. Even then he had mixed emotions about leaving. My feelings weren’t so complex; I was just sad to see him go. In a job recommendation I wrote for him a few weeks later, I was honest: “I feel that Ric’s leaving was a great loss to Microsoft.”

I don’t know if our company lunch that week prompted what happened next, but Microsoft got a lucky break: Bob Greenberg, who had worked with us for less than a month, told me he would loan Microsoft $7,000, enough to help make our payroll. Years later, neither Bob nor I could remember whether I asked or he offered, but the loan transpired, with the agreement that Microsoft would pay him interest of eighty dollars a month. (When he learned of the loan, Bob’s father chastised him. Already upset that he’d taken the job at Microsoft and not at a brand-name company, he said, “When you get a job, they pay you. You do know that, right?”)

Hoping I could drum up more money, a day after receiving Bob’s loan I wrote Apple:

Dear Mr. Wozniak:

Enclosed please find our standard licensing contract. I believe I already communicated the price for 6502 BASIC to you:

OPTION1:

$1,000.00 flat + $2,000.00 for source + ($35.00/copy to a max of $35,000.00)

OPTION2:

$21,000.00 flat: includes source and full distribution rights for object

We could work out an option in between these if you are interested. Because of your inhouse software expertise and special hardware you will probably want the source…

…If you want another demo version or you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I look forward to our resolving a mutually beneficial licensing arrangement.

Bill

A few weeks later I got a phone call from Apple’s president, Michael Scott, who said that his company liked the second option. Within a couple of days a check arrived for half the fee: $10,500. With that I paid more salaries and sent our lawyer another $1,000 nibble at our growing legal fees.

That same month, Tandy, known for its national chain of RadioShack electronics stores, announced the TRS-80 home computer, becoming the next major company to jump in the market. Within a month, RadioShack sold a surprising ten thousand TRS-80s, which made it a runaway hit. The RadioShack machine was a more complete system than the Altair and other hobbyist computers. Starting at $599.95, it came with a keyboard, a monitor, and a cassette recorder, and was ready to use out of the box. With the computer, Tandy included its own version of BASIC, which it had based on the free Tiny BASIC. Called Level 1 BASIC, it was so limited that Tandy quickly heard back from angry customers. Though we had missed the machine’s debut, I hoped to persuade Tandy to buy our software. I set up a meeting at the company’s headquarters for late September.

Right after Labor Day, I flew to Seattle for Kristi’s wedding and made time to talk to my dad about my upcoming meeting with Tandy. I knew that the technical people at Tandy were fans of our BASIC, but I would have to convince the executive who headed the group of its value. Though I had never met John Roach, I had heard he was tough—a native Texan known to be gruff.

I knew that Tandy was a company that bought capacitors, resistors, and toggle switches by the ton. It employed specialist “buyers” whose sole job was to squeeze pennies from the Asian companies that supplied the thousands of products RadioShack sold in its stores. Tandy’s low-cost culture meant that the computer division had developed the first TRS-80 for less than $150,000. It got a bargain on RCA TVs that it would sell as displays for the TRS-80s. Those TVs’ outer shells happened to be gray, so to keep things cheap, the whole TRS-80 became gray.

My pitch, I told my dad, was that Microsoft could sell BASIC at a price far lower than Tandy could write a version on its own. I drafted two pages of talking points about how much better our product stacked up against anything else out there. My dad had advised me to simply be honest with Roach. If anything, he just gave me confidence. If I offered a great price and explained why it was a great price, Roach would probably listen. My dad said I could even go so far as to break down Microsoft’s cost structure so he understood my thinking.

Walking into Tandy’s Fort Worth headquarters, I was primed to confidently lay out the benefits of our BASIC and offer them a cut-rate deal. We had charged TI $90,000, but that required a new chip and a lot of custom work. For RadioShack, I decided we would ask for $50,000.

We all stood around a table: me, the company’s software guy, a few others, and John Roach. I ran through my carefully crafted sales pitch.

As I talked, Roach stood there, his chin jutting out, not giving any indication of whether what I was saying had any effect. He might have said something, I don’t remember, but I couldn’t help feeling that he was resistant.

As I spoke, I found it difficult to contain my excitement. “You’ve got to do this!” I implored. “Without our BASIC your computer won’t be able to do anything!” At this point, I was flying way off script. “With our BASIC you’re golden!” I added.

This was more than bluster. The depth of thinking and the work we were putting into BASIC were leagues beyond any available. I really believed in our work. At that point, I had my palms flat on the table and was leaning across it toward Roach, whose face was a vivid shade of red.

He asked me how much it would cost.

“Fifty thousand dollars,” I said. A flat fee.

Roach’s response remains one of the most memorable moments from my early days of Microsoft. “Horseshit!” he growled. Wow, that wasn’t in the script. It was also the kind of thing that I could have heard myself saying, though maybe without the barnyard color. I decided in that meeting that I liked John Roach. And I liked RadioShack. They were very good businesspeople. It helped too that despite his reaction that afternoon, Horseshit Roach, as we’d come to call him, agreed to our price.

By the time I visited RadioShack, we had heard from the arbitrator in the MITS case: He sided with Microsoft. He terminated our exclusive 8080 BASIC license with MITS, clarifying definitively that we owned our source code.

Much of the arbitrator’s ruling focused on Pertec’s attempts to stop MITS from licensing BASIC to competitors and the fact that it used our software in developing its own version of BASIC, which the arbitrator described as “an act of corporate piracy not permitted by either the language or any rational interpretation of the Contract.”

We immediately called all the companies that had been waiting for the software. Within weeks we had money coming in from five or six clients, including ADDS and its “Centurion” Project, or whatever it was called. We would make our own best efforts to license our software, and with MITS out of the picture, we didn’t have to split the revenue.

In late October I sent Paull Mines the outstanding balance we owed him, writing that “I hope I am not speaking too soon when I say I feel like this marks the closing of our adventure with MITS. Not only was the outcome favorable but the experience was exciting and enjoyable, both of which you are largely responsible for.” Paull would continue to be a trusted advisor for me and Microsoft for several years.

Pertec’s deal to buy MITS had closed in late May. Ed came away from the merger with a few million dollars and a choice job running a lab at Pertec tasked with ginning up the next technology hit. But from the start, Eddie Currie and our other MITS friends said Pertec was a bad fit. MITS was scrappy and loose, innovative in its own way. Pertec was buttoned-down, and overconfident in its ability to navigate the fast-changing world of personal computers. It very quickly smothered the smaller company. Steadily the Altair lost market share. Ed proposed a plan to sell a laptop computer, but Pertec shot it down, unconvinced there was a market for such a thing.

When Ed was growing up in Florida, he had wanted to become a surgeon and carried around laminated human anatomy study cards; at one point he even did a stint in a hospital as a scrub tech. After a short period at Pertec, Ed quit and moved his family to the small town of Cochran, Georgia. He ran a farm for several years before following his childhood dream: at age forty-four he graduated from Mercer University with his medical degree. For the rest of his life, Ed operated a small clinic that served rural Georgians.

My relationship with Ed was complicated but also one of the most formative in my early career. Around the time Microsoft won the arbitration, I had stopped by to see him in his office at MITS. He said he felt burned by the decision and thought the arbitrator had misunderstood the situation. “Next time, I’ll hire a hit man,” he quipped. Without question he was joking, but he didn’t laugh. As our paths diverged, we saw each other less and less. In 2009, when I heard that Ed was hospitalized with pneumonia, I called him. We hadn’t talked in many years, but I knew he still felt some ill will. On the call, I told him that I wanted him to know that I learned a lot from him when we worked together, something I never would have said at the time. “I was very immature and a bit arrogant, but I’ve changed a lot since then,” I told him. That seemed to break the ice, and we had a great talk. “We did a lot of good, important work,” he said. I agreed: we really did.

A few months later, when Ed’s condition worsened, I flew to Georgia to visit him. He was hardly conscious, but for a couple of hours I talked to him and with his son David, recounting the early days of the industry. He died not long after, in April 2010, at age sixty-eight. Beyond being the first to market a commercially successful personal computer, Ed Roberts wrote the blueprint for how the personal computer industry would develop. MITS’s newsletter was the first magazine devoted to PCs. The company sponsored the first PC trade show. The first computer stores were Altair dealers, and user groups that sprung up around the machine catalyzed the founding of important companies—including Apple. Yet during our talk, David told me his dad felt that his achievements as a small-town doctor were as meaningful as all he had done to start a technology revolution.

By the end of 1977, the Commodore PET, Apple II, and RadioShack TRS-80 started to make their way into schools, offices, and homes, within a few years reaching hundreds of thousands of people, most of whom had never touched a computer. Unlike the first generation of hobbyist machines, all three computers were fully assembled and ready to use, no soldering iron required. The PET came with lots of features, including a built-in cassette recorder for storing data and programs, while its limited keyboard—with frustratingly tiny keys that reviewers compared to Chiclets chewing gum—didn’t stand in the way of its success. Over the next year Tandy updated the TRS-80, adding new features and leveraging its five thousand RadioShack stores to reach customers at a scale that other companies could not. Sales of the Apple II grew quickly, propelled by smart marketing, ingenious design, and color graphics, which made it especially great for game playing.

Later known as the “1977 Trinity,” those three machines introduced the personal computer revolution into the mainstream as others fell behind. (TI, the feared giant we had been so excited to work with, never succeeded in PCs.) Installed on each member of the Trinity was a version of our BASIC that we had tailored to the requirements of their maker. In RadioShack’s machine it was Level II BASIC, on the Apple it was Applesoft—an amalgam of its name and ours—and the PET was simply Commodore BASIC. In a version for Commodore we squeezed a little surprise into the code: if a PET user happened to enter the command WAIT 6502,1, one word would appear on the upper left of their screen: MICROSOFT!

With Microsoft no longer dependent on MITS and Paul and me having trouble hiring programmers in Albuquerque, in the spring of 1978 I wrote a memo for our ten or so employees, listing possible options for Microsoft’s permanent home. I included Seattle, Dallas–Fort Worth—which was close to our big customers Tandy and TI—and Silicon Valley, which had a critical mass of customers, people to hire, but also competitors. Paul felt the pull of our hometown. He was sick of the Albuquerque heat, craved Seattle’s lakes and the Puget Sound, and wanted to be closer to his family. Most of our employees were open to any of our options (though a few wanted to stick in Albuquerque). After giving it a lot of thought, I concluded that Seattle ticked the most boxes: The University of Washington was a great source for programmers, and the distance from Silicon Valley afforded a higher degree of secrecy and a lower risk of losing employees to rivals. And, of course, that was my mom’s preference as well. Once we decided on Seattle, she couldn’t resist sending real estate listings she clipped from the paper, often adding her take (“this would be very convenient to the bridge—a good possibility I think”).

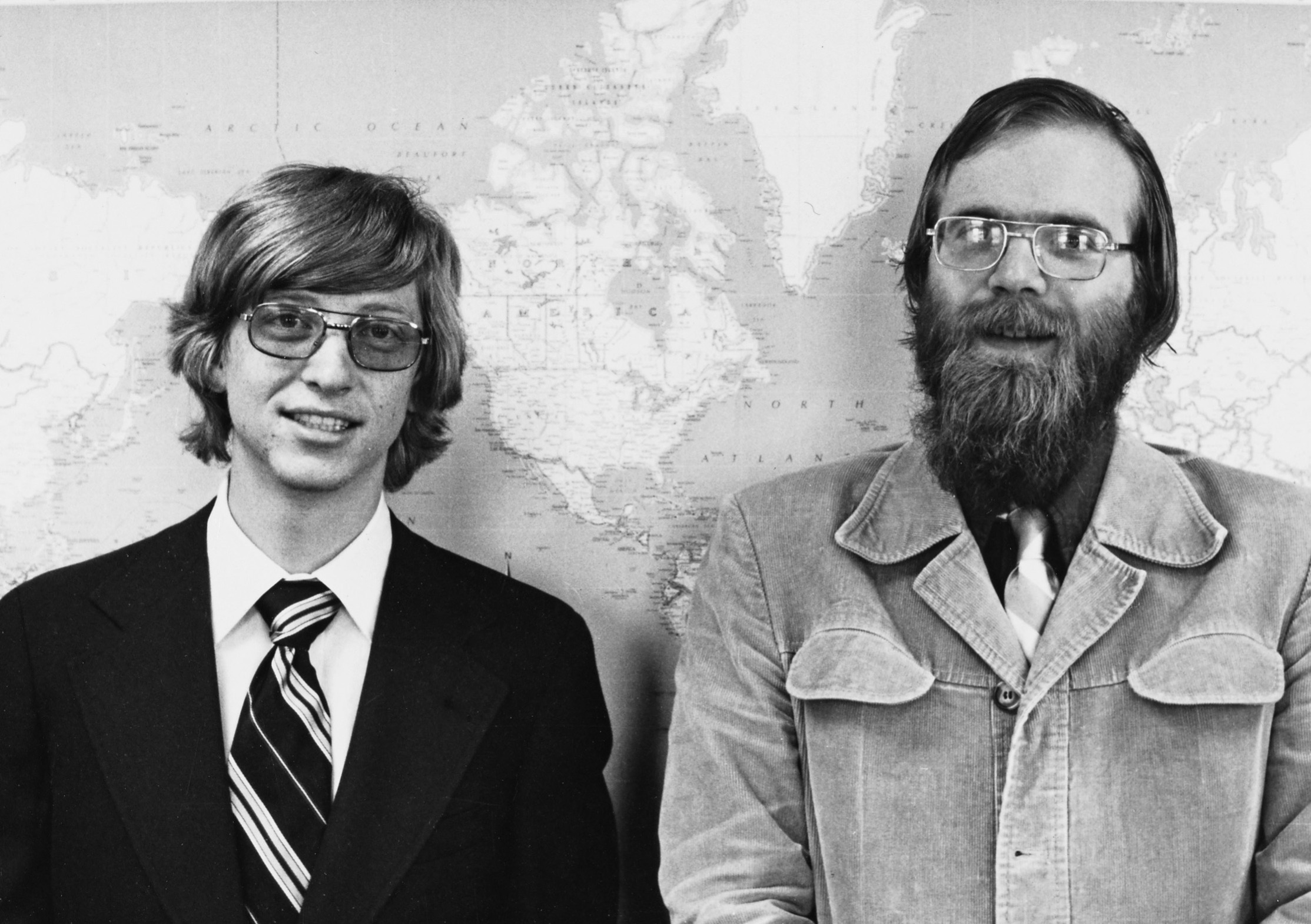

In December 1978, our last full month in Albuquerque, Bob Greenberg won a contest prize of a free family portrait. He sent out a memo with the subject “Esprit de Corps,” asking everyone to come to the photo studio behind Shanghai restaurant. The family he brought was eleven of our twelve employees (one was home that day). The picture we sat for would become an iconic photo of 1970s Microsoft, complete with wide collars, shaggy hair, and five bushy beards.

About a month later, I crammed what little I owned into my 911, inserted a cassette of The War of the Worlds—on loan from Paul—into the tape deck, and headed north through Nevada to Silicon Valley for a handful of meetings, then up to Seattle. I remember the trip for the three speeding tickets I got. I also remember thinking about how odd it was to be moving home. When I left for college, I’d told my parents that I would never live in Seattle again; it seemed a given that I would build my life out in the larger world. In my mind that would be the East Coast, the center of finance, politics, top universities, and—back then—the computer industry. Returning could be seen as a retreat.

But as I thought about it, I realized this was different. It wasn’t just me moving back, it was Microsoft—the company that a friend and I had co-created, with that motley group of employees and a growing, profitable business, and which from that point on would be an integral part of who I was. My path was set. As I sped along I-5 at a hundred miles an hour, I could hardly imagine how far it would take me.